1. Probiotics against Viral Infection

Probiotics are a beneficial live microorganism which, when administrated in sufficient quantity (at least 106 viable CFU/g), are known to participate in metabolism, improving the microbial balance in the gut

[1][2][3]. Probiotics of mainly the strains of lactic acid bacteria, in particular

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium genera, show various health effects

[4]. Their well-established properties have been extensively studied, primarily modulating the gut microbiota via the growth suppression of opportunistic bacteria

[5]. Beyond the gut, probiotics have been reported to exert beneficial health effects through several potential mechanisms, including immunomodulation, epithelial barrier function maintenance, and signal transduction modulation

[6].

Viral infectious diseases are a primary contributor to the global burden of death and disability

[7]. Both developed and developing countries struggle against the alarming rise in infectious diseases

[8]. The best current example of this global threat is the novel COVID-19, with millions of people afflicted. Despite the success of therapeutic and preventive strategies against the disease, concerns remain with the continued reporting of new viral variants

[9][10]. As a result of infectious disease, profound damage to multiple organs, including the respiratory tract, liver, colon, and more, supports the urgent need for alternative strategies against viral infection. Notably, a diverse microbial community inhabits about every part of the human body, mainly in the intestine

[11]. A stable and healthy microbial community is able to protect the human host from a variety of pathogen infections by preventing viral infectivity through a diverse mechanism and exerting substantial inhibitory effects

[12]. As such, probiotics serve as a complementary strategy, given their beneficial effects against viral disease by potentiating immune response, maintaining the epithelial barrier, and binding to the pathogen to skew its attachment. These antiviral effects of different strains of

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium have been studied on both gastrointestinal and respiratory viruses (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Probiotics strains against respiratory (influenza A virus H1N1, H3N2, and respiratory syncytial virus) and gastrointestinal viruses (rotavirus). The figure represents some examples of different strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium studied for the antiviral effects against viruses.

More than 70% of the body’s immune cells are located in the GI tract, indicating a direct connection between the immune system and intestinal microflora, which provide some relationships with GI viruses

[13]. Some studies have revealed the immunomodulation effect of

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium against rotavirus (RV), one of the leading global causes of life-threatening diarrhea in children under the age of five

[14][15]. RV alters the human gut microbiome by shifting the dominant phylum from

Bacteroidetes to

Firmicutes, decreasing bacterial diversity, and increasing opportunistic pathogens, such as the genera

Shigella [16]. Both

Lactobacillus reuteri strains ATCC PTA 6475 and DSM 17938 augmented mucosal RV-specific antibodies in infected neonatal mice and attenuated diarrhea symptoms

[17]. The nutritional status of body mass index—normal weight, underweight, and overweight—may impact the response of probiotics on RV. Underweight mice had fewer RV-specific antibodies than the other two groups. In another study, the combination of

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG with specific bovine colostrum-derived immunoglobulins significantly decreased the severity and duration of diarrhea in an infant mouse model

[18]. Both

Bifidobacterium bifidum and

Bifidobacterium infantis contributed to delaying clinical diarrhea in RV-infected mice

[19].

Furthermore, the probiotics also enhanced the immune response, resulting in a high elevation of specific IgA.

Bifidobacterium longum subspecies

infantis, which was incubated in cell cultures prior to infection, showed the ability to reduce RV infectivity in both HT-29 and MA-104 cells in vitro

[20]. Additionally, the in vivo study applied on a BALB/c mouse model revealed that viral shedding in stools was decreased in probiotic-fed mice challenged with RV, compared to control mice. In experiments with piglet models,

Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 diminished the severity of diarrhea, and fecal RV concentration was also reduced

[21]. Additionally,

Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 elevated the immune response in infected piglets; particularly, specific IgG, IgA, and IgM concentrations in fecal samples were observed.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG also decreased the severity of RV infection in a gnotobiotic pig model

[22]. According to previous studies, despite the success of vaccine development against RV, the gut microbiota for unvaccinated and vaccinated people has no differences

[23][24]. The combination of probiotics and vaccination has been studied, proving that able to improve the gut microbiota efficiently.

Lactobacillus acidophilus increases the immunogenicity of an oral RV vaccine, enhancing the IgG and IgA antibody-secreting cell responses

[25].

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and

Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 act as immunostimulants for RV vaccine via differential toll-like receptor signaling which modulated dendritic cell responses

[26]. Therefore, probiotics are still considered a need as an adjuvant for the RV vaccine.

Besides GI viruses, probiotics and microbiota have been proven to have an antiviral effect on respiratory viruses, including the fatal seasonal scourge—influenza virus

[27]. Influenza causes about 20,000 deaths based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimation for 2019–2020 (

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html, accessed on 28 November 2021). A mounting body of evidence shows that nasally and orally administered probiotics can enhance the resistance against respiratory viral infections. A heat-killed

Lactobacillus casei DK128 showed an effect on mice infected with H3N2, resulting in a lower viral titer in heat-killed DK128 treated mice compared to the mock-treated mice group

[28]. Moreover, a higher quantity of alveolar macrophage cells was found in the lung and airways of heat-killed DK128 treated mice. Alveolar macrophages, in the interphase between lung tissues and air, can provide the first line of innate immunity against the influenza virus

[29]. In another study, alveolar macrophages were shown to release many inflammatory cytokines that helped control viral replication

[30]. The

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG administration was carried out to investigate the anti-H1N1 ability

[31]. The survival rate was roughly 60% and 20% for

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-treated mice and the control groups, respectively. Of note, a significant increase in NK cell activity was observed in

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG group compared to untreated group. Another strain of probiotics,

Lactobacillus pentosus S-PT84, also exerted a strong induction of IL-12 and high IFN-γ production in mediastinal lymph node cells, contributing to the high improvement of survival rates and reducing H1N1 virus titer in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

[32]. Similarly, the intranasal administration of

Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota stimulated the IL-12 production and NK cell activity, resulting in adequate protection against H1N1 infection

[33]. Additionally, there was an increase of IgA in the nasally administered mice with

Lactobacillus fermentum CJL-112, leading to the antiviral effect against influenza A/NWS/33 (H1N1)

[34]. In another study,

Lactobacillus plantarum AYA induced the increase of IgA production in lung and small intestine in the H3N2 infected mice

[35]. The rise of IgA and IgG production was also observed in the H1N1-infected mice treated with

Lactobacillus pentosus strain b240

[36]. Two other strains of

Bifidobacterium, including

Bifidobacterium longum 35624 and

Bifidobacterium longum PB-VIR, also induced the reduction of viral load and improved survival rate in mice challenged with influenza virus strain PR8 (A/Puerto Rico8/34, H1N1)

[37].

Besides the influenza virus, the human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) also showed a specific correlation with the gut microbiota and probiotics

[38][39]. RSV is an enveloped negative-strand, non-segmented RNA virus of the

Paramyxoviridae family, which primarily causes severe respiratory disease in infants and children

[40]. RSV-related lower respiratory tract infection was associated with roughly 48,000–74,500 deaths in children aged less than 5 years in 2015

[41]. The oral administration of

Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 (LG2055) leads to a significant decrease in RSV titer in the lung

[42]. Another probiotic strain,

Lactobacillus rhamnosus CRL1505, also showed the capacity of reducing lung viral in a study where CRL1505 was orally administered to infant mice infected with RSV

[43]. It was found that the increase in IL-10 and IFN-γ secretion after CRL1505 treatment would modulate the pulmonary innate immunity, leading to the activation of dendritic cells and the generation of Th1 cells. Similar results were also obtained when CRL1505 was nasally administered

[44].

2. Gut-Lung Axis Associated with COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2 primarily infects the respiratory tract by attaching to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor

[45]. This receptor is expressed in different organs and is highly expressed on the surface of the type-II alveolar epithelial cells and airway epithelial cells. Despite the respiratory system being the leading target site of the virus, the GI tract is also an important target, contributing to GI symptoms, including nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting

[46]. Studies have shown that coronavirus viral RNA can be detected in urine and fecal samples from COVID-19 patients

[47]. The alteration of intestinal flora composition (dysbiosis) has been reported for COVID-19 patients (

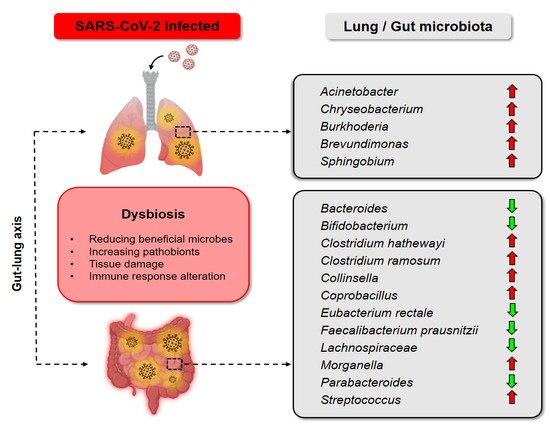

Figure 2). These findings suggest the importance of understanding the gut-lung axis (GLA) for the management of COVID-19.

The GLA, herein, refers to bidirectional interactions between the respiratory mucosa and the gut microbiota, with the ultimate goal of modulating the immune response

[48]. It is widely known that the gut has a large amount of microbiota exerting a marked effect on host homeostasis and disease

[49]. A healthy lung has also been demonstrated to have its own specific microbiota, including

Prevotella,

Streptococcus,

Veillonella,

Fusobacterium, and

Haemophilus [50][51]. Although there is a limited understanding of the impact on the microbiome in the disease etiology, gut dysbiosis has been proved to increase the risk of diseases

[52]. For instance, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) causes inflammation and promotes respiratory tract infection, supporting the crosstalk between lung and gut microbiota

[53]. A high percentage of COVID-19 patients demonstrate GI symptoms. The gut bacterial diversity of COVID-19 patients was significantly reduced compared with healthy controls

[54]. Several gut commensals with immunomodulatory effects, such as

Eubacterium rectale and

Bifidobacterium, were underrepresented in patients

[55], while

Collinsella,

Streptococcus, and

Morganella were significantly increased in patients with high SARS-CoV-2 infectivity

[56]. Zuo and colleagues found increased levels of

Parabacteroides,

Bacteroides, and

Lachnospiraceae in patients with low or no SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. These bacteria are able to produce short-chain fatty acids, which play an important role in boosting the host immunity

[57]. The relative abundance of

Coprobacillus,

Clostridium ramosum, and

Clostridium hathewayi was positively correlated to COVID-19 severity. Conversely,

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and

Bacteroides were inversely correlated to COVID-19 severity

[58][59][60]. Strikingly, the microbiota composition in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) patients is similar to COVID-19 patients.

Figure 2. Dysbiosis of gut and lung in COVID-19 patients. In the lung of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients,

Acinetobacter,

Chryseobacterium,

Burkhoderia,

Brevudimonas, and

Sphingobium were prevalent

[61]. The gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients was also altered, with the decrease of

Bacteroides [56],

Bifidobacterium [55],

Eubacterium rectale [55],

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [60],

Lachnospiraceae [56],

Parabacteroides [56], and the increase of

Clostridium hathewayi [58],

Clostridium ramosum [58],

Collinsella [56],

Coprobacillus [58],

Morganella [56],

Streptococcus [56].

2.1. Rationale of Probiotics as an Adjunctive Treatment for COVID-19

Gut microbiota abnormality increases the susceptibility of an individual to various diseases. Emerging evidence suggests that probiotics are beneficial in the control of COVID-19. Probiotics are known for restoring stable gut microbiota through the interaction and coordination of the intestinal innate and adaptive immunity. Various types of cells, such as mast cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and macrophages, interact with the gut microbiome to regulate innate immunity. For instance, antigen-presenting cells, comprising dendritic cells in the Peyer’s patches of the intestine, Langerhans cells, and macrophages, have some tolerant immunogenic properties

[62]. B and T lymphocytes are mainly involved in the adaptive system. The increased level of naïve T helper (Th) lymphocytes and decreased levels of NK cells, B lymphocytes, and memory Th lymphocytes have been observed in COVID-19 patients. The immune homeostasis of the gut can affect the immunity of the lung via GLA. This is probably through a deregulated immune response, with an increase of IFN-γ, IL-6, CCL2, and a decrease of regulatory T cells in the lung and GI tract

[63].

Probiotics are considered harmless, originating from the fermentation of food—an ancient form of food preservation and widely used as food additives

[64][65]. Probiotics are measured in colony-forming units (CFU), indicating the number of viable cells

[66]. The amount of probiotics is usually written as 5 × 10

9 for 5 billion CFU or 1 × 10

10 for 10 billion CFU on the commercially available probiotics products. Various probiotic products contain different probiotic amounts, but the standard effective dosages for adults are from 10 to 20 billion CFU. In comparison, the dosages for children are recommended at around 5 to 10 billion CFU

[67]. The higher the dosages of probiotics used, the higher the beneficial outcome may be expected. There is no evidence that overdosage of probiotics is of health risk concern

[67].

Several concerns of probiotics safety should be considered, such as antibiotic resistance and their toxicity on the GI tract

[68]. Although probiotics have been shown not to exhibit toxic effects, there are still rare cases of bacteremia involving probiotics, observed in immunocompromised individuals

[64]. The guidelines for the safety assessment of probiotics are highly stringent, particularly in relation to the identification of the risk factors for both probiotics and the host, followed by the verification of the risks in the interaction between the used probiotics and the host

[69]. Hence, this does not only evaluate the beneficial effects of probiotics but also their side effects. Moreover, to further evaluate the safety of probiotic products, epidemiological surveillance of adverse incidents in human use is implemented

[70]. Accordingly, the usage of probiotics as an adjunctive treatment against COVID-19 can be expected in the future as a modulator of immune response to decrease pathogenic microbiome in the host.

2.2. Clinical Evidence That Supports Probiotics as a Promising Anti-COVID-19 Strategy

The consumption of probiotics is considered to relieve COVID-19 symptoms by boosting immune host response and improving gut microbiota

[71]. The use of probiotics may indicate its ability to combat SARS-CoV-2 or its associated symptoms through evaluation of antiviral and anti-inflammatory probiotic effects, in vitro, in vivo, and clinically

[72]. A review suggested that enhancing the intestinal microbiota profile by personalized diet and supplementation, especially with probiotics, can improve the immune system for combatting COVID-19

[73].

Given the important relationship between probiotics, microbiota, and COVID-19, several researchers directly focused on probiotics that may have a high antiviral effect on COVID-19. Seven clinical trials studying the effects of probiotics on COVID-19 have been reported, with six completed (

Table 1). A clinical study of 123 SARS-CoV-2 infected patients with severe symptoms, treated with a mixture of probiotics such as

Lactobacillus acidophilus and

Bifidobacterium infantis, showed clinical evidence that probiotics could moderate the immune function and reduce secondary infection

[74]. In another study, a team conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a novel probiotic formulation in COVID-19 outpatients

[75]. Patients aged from 18 to 60 years were treated with a probiotic formulation of three strains of

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum (KABP022, KABP023, and KAPB033), together with one strain of

Pediococcus acidilactici KABP021 or were given a placebo, which they took orally once daily for 30 consecutive days. In this study, remission, defined as a negative RT-qPCR and symptom clearance, was assessed. The remission proportion for the probiotic-treated group was at ~53.1%, significantly higher than that of the placebo group (~28.1%). Separately, another study showed that the high consumed quantity of fermented vegetables or cabbage might be associated with a low COVID-19 death rate in some countries in Eastern Asia and Central Europe

[76].

Table 1. Clinical trials on the effect of consuming probiotics against COVID-19. The data is up-to-date as of 28 November 2021, retrieved from

https://clinicaltrials.gov/. The search query was “condition or disease” = “covid19”, “other terms” = “probiotics.”.

| No. |

Identifier |

Title |

Treatment |

Probiotic Strain |

Number Enrolled |

Status |

| 1 |

NCT04517422 |

Efficacy and safety of Lactobacillus plantarum and Pediococcus acidilactici as co-adjuvant therapy for reducing the risk of severe disease in adults with SARS-CoV-2 and its modulation of the fecal microbiota: A randomized clinical trial |

Once per day, administered for 30 days |

Combination of 4 probiotic strains, including 3 Lactobacillus plantarum strains CECT30292, CECT7484, CECT7485, and Pediococcus acidilactici strain CECT7483 |

300 |

Completed |

| 2 |

NCT04458519 |

Clinical study of efficacy of intranasal probiotic treatment to reduce severity of symptoms in COVID-19 infection |

Twice per day, administered for 14 days |

Lactococcus lactis W136 |

23 |

Completed |

| 3 |

NCT04854941 |

Efficacy of probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis and Bifidobacterium longum) in the treatment of hospitalized patients with novel coronavirus infection |

3 times per day, administered for 14 days |

Combination of 4 probiotic strains, including Lactobacillus rhamnosus PDV 1705, Bifidobacterium bifidum PDV 0903, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis PDV 1911 and Bifidobacterium longum PDV 2301 |

200 |

Completed |

| 4 |

NCT04399252 |

A randomized trial of the effect of Lactobacillus on the microbiome of household contacts exposed to COVID-19 |

2 capsules per day, administered for 28 days |

Lactobaciltus rhamnosus GG |

182 |

Completed |

| 5 |

NCT04734886 |

Exploratory study for the probiotic supplementation effects on SARS-CoV-2 antibody response in healthy adults |

2 capsules per day, administered for 6 months |

Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 |

161 |

Completed |

| 6 |

NCT05043376 |

A randomized, open-label, and controlled clinical trial to study the adjuvant treatment benefits of probiotic Streptococcus salivarius K12 to prevent/reduce lung inflammation in mild-to-moderate hospitalized patients with COVID-19 |

2 tablets per day, administered for up to 14 days |

Streptococcus salivarius K12 |

50 |

Completed |

| 7 |

NCT04366180 |

Multicentric study to assess the effect of consumption of Lactobacillus coryniformis K8 on healthcare personnel exposed to COVID-19 |

Once per day, administered for 8 weeks |

Lactobacillus coryniformis K8 |

314 |

Ongoing |