| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Soghra Bagheri | + 1571 word(s) | 1571 | 2022-01-10 04:25:56 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | Meta information modification | 1571 | 2022-01-14 03:43:59 | | |

Video Upload Options

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that eventually leads the affected patients to die. The appearance of senile plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients is known as a main symptom of this disease. The plaques consist of different components, and according to numerous reports, their main components include beta-amyloid peptide and transition metals such as copper. In this disease, metal dyshomeostasis leads the number of copper ions to simultaneously increase in the plaques and decrease in neurons. Copper ions are essential for proper brain functioning, and one of the possible mechanisms of neuronal death in Alzheimer’s disease is the copper depletion of neurons. However, the reason for the copper depletion is as yet unknown.

1. Introduction

2. Insights and Concluding Remarks

The grey matter and certain areas of the brain like the hippocampus that are the most damaged in AD have been reported to contain the highest levels of copper in a healthy brain [25][26]. The brains of patients with AD are copper deficient [12][14][15][16][17][18][19][27], and a dataset led to the hypothesis that this deficiency can consequently lead to channel creation in the neuron membrane, which results in apoptosis [22][27]; however, the cause of this deficiency is not yet known.

Recently, a critical, location-dependent copper dissociation constant (Kdc) was proposed as a new mechanism, featuring a shift from physiological bound metal ion pools to loose toxic pools in copper imbalance (reviewed in [11]). This hypothetical mechanism provided some clues on the key decreased copper enzymes and transporters in the AD brain that can majorly affect copper buffering and functioning in synapses during the glutamatergic transmission process. The concept proposed is applicable to Aß and APP as well as other copper proteins relevant to the AD cascade, including the prion protein and ∝-synuclein [11].

Another putative mechanism of copper deficiency in neuronal cells lies in Aß sorting and segregation within lipid rafts. Of note, Aß is produced in lipid rafts [28][29] before entering the synaptic space or being digested inside the neuron [30]. In AD, it seems that Aß production increases or its clearance decreases, and binding of copper ions to this peptide (with a high affinity for copper ions) or deposition outside the cell can lead to copper deficiency in neurons. The findings indicate that the Aß is greatly deposited in areas of the brain with the most damage. As well as this, greater deposition may cause more intense apoptosis due to greater copper deficiency.

Certain evidence suggested that microglia activation can be considered as another possible cause of copper deficiency in neurons. Copper is unevenly distributed in the brain, and some brain areas contain greater amounts of copper. One such area is the hippocampus, which is related to memory and becomes severely damaged in AD [25][31]. Neurons of this area routinely use copper to prevent excitotoxicity by NMDA receptors, and also release copper at the micromolar level after each depolarization to synapses [32][33]. Aß deposits have also been shown to activate microglia, and the activated microglia then clear amyloid from the environment [34]. Meanwhile, the activated microglia increase the expression of copper-related proteins, which consequently causes copper uptake into the microglia [35]. Also, a new study confirmed that microglia increase their intracellular copper in response to the inflammatory stimuli [36]. Therefore, it seems that if microglia are activated in the areas using copper to prevent excitotoxicity by NMDA receptors, by microglia absorbing copper from the synaptic space, copper re-uptake by neurons can be disrupted, which consequently causes a serious copper deficiency in neurons. Correspondingly, this phenomenon can cause overactivation of NMDA receptors and subsequently lead to neurodegeneration. Moreover, it was found that copper imbalance in the heart is dangerous. Loss of copper from the heart occurs in myocardial ischemia [37][38]. Recently, in an animal study, it was shown that upregulation of an intracellular copper exporter, such as copper metabolism MURR domain 1 (COMMD1), in the heart is key to exporting copper from the heart to the blood on ischemic insult [39]. Accordingly, this mechanism can also take place in the brain in AD, especially in the hippocampus. In addition, the upregulation of CTR1 in microglia can function to absorb the copper released from neurons.

NMDA receptors seem to regulate different processes in various brain regions [40][41]. Accordingly, they have different distributions in the central nervous system in terms of their type of subunit [42]. For instance, NR2A and NR2B are overexpressed in the cortex and hippocampal areas, respectively, while high NR2C expression is specific to the cerebellum area [42][43]. On the one hand, the earliest instance and highest level of damage were found to be related to the cortex and hippocampal areas, respectively, while the lowest was related to the cerebellum area [44][45]. On the other hand, the cortex and hippocampus have the highest levels of copper in the brain. Taken together, this evidence suggests that activation of microglia in the presence of copper-regulated NMDA receptors may be a significant factor in copper deficiency in neuronal cells.

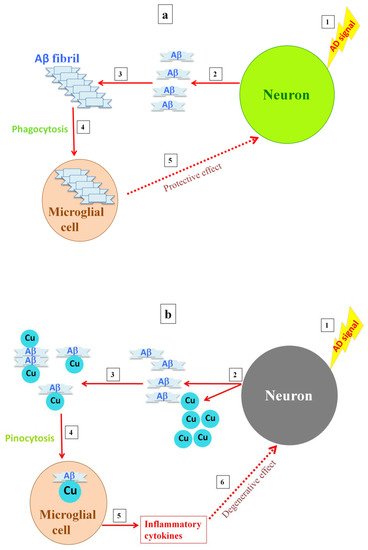

In addition, the activation of microglia in areas using copper to prevent excitotoxicity by NMDA receptors can lead to copper deficiency through another mechanism. Copper reduces the phagocytic properties of microglia, which can consequently result in greater Aß deposition [46][47]. Logically, a greater increase of Aß deposition in this area would lead greater amounts of copper to be deposited out of reach of neurons. Otherwise, evidence has shown that copper intensifies Aß-mediated microglia activation, and subsequently, highly activated microglia do not play a protective role, which leads to neuronal death [48] (Figure 1). However, previous studies have shown that microglia form a barrier around small amyloid plaques, and slowing of the dystrophic neural process can be detected in areas with microglial coverage, suggesting peptide clearance by microglia protects neurons against Aß toxicity [49].

Figure 1. Postulated differences in microglia activity with either the absence or presence of a high copper concentration. When high levels of amyloid are released into the synapse, amyloid fibrils are formed and the microglia are activated, clearing the fibrils by phagocytosis (a). Releasing high levels of copper into the synapse, as copper inhibits the NMDA receptor, results in soluble A deposits, which are then taken up by microglia via pinocytosis, causing overactivation of the microglia and inflammation (b).

In general, copper imbalance in AD, similar to the disease itself, is a complex phenomenon. In this review article, we attempted to specifically address the possible causes of copper depletion in neurons. We hypothesized that there may be two possible causes of copper depletion in neurons: first, the release of amyloid (as a copper transfer protein with a high affinity for copper) from neurons and its deposition outside neurons can trap copper outside neurons, which in turn, causes copper deficiency in neurons. Second, the uptake of copper by the activated microglia makes copper inaccessible to neurons.

References

- Yun-Wu Zhang; Robert Thompson; Han Zhang; Huaxi Xu; APP processing in Alzheimer's disease. Molecular Brain 2011, 4, 3-3, 10.1186/1756-6606-4-3.

- Alzheimer’s Disease International World Alzheimer Report 2019: . https://www.alzint.org/. Retrieved 2022-1-12

- Pei-Pei Liu; Yi Xie; Xiao-Yan Meng; Jian-Sheng Kang; History and progress of hypotheses and clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2019, 4, 1-22, 10.1038/s41392-019-0063-8.

- Kasper Planeta Kepp; Ten Challenges of the Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2016, 55, 447-457, 10.3233/JAD-160550.

- Soghra Bagheri; Ali A. Saboury; What role do metals play in Alzheimer's disease?. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 2021, 18, 2199-2213, 10.1007/s13738-021-02181-4.

- De Benedictis, Chiara A.; Vilella, Antonietta and Grabrucker, Andreas M.. The Role of Trace Metals in Alzheimer’s Disease; De Benedictis, Chiara A.; Vilella, Antonietta and Grabrucker, Andreas M., Eds.; Codon Publications: Brisbane, 2019; pp. chapter6.

- Stefano L. Sensi; Alberto Granzotto; Mariacristina Siotto; Rosanna Squitti; Copper and Zinc Dysregulation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2018, 39, 1049-1063, 10.1016/j.tips.2018.10.001.

- Ashley I. Bush; Rudolph E. Tanzi; Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease based on the metal hypothesis. Neurotherapeutics 2008, 5, 421-432, 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.001.

- Rosanna Squitti; Ilaria Simonelli; Emanuele Cassetta; Domenico Lupoi; Mauro Rongioletti; Mariacarla Ventriglia; Mariacristina Siotto; Patients with Increased Non-Ceruloplasmin Copper Appear a Distinct Sub-Group of Alzheimer's Disease: A Neuroimaging Study. Current Alzheimer Research 2017, 14, 1318-1326, 10.2174/1567205014666170623125156.

- Rosanna Squitti; Mariacarla Ventriglia; Massimo Gennarelli; Nicola A. Colabufo; Imane Ghafir El Idrissi; Serena Bucossi; Stefania Mariani; Mauro Rongioletti; Orazio Zanetti; Chiara Congiu; et al.Paolo M. RossiniCristian Bonvicini Non-Ceruloplasmin Copper Distincts Subtypes in Alzheimer’s Disease: a Genetic Study of ATP7B Frequency. Molecular Neurobiology 2016, 54, 671-681, 10.1007/s12035-015-9664-6.

- Kasper P. Kepp; Rosanna Squitti; Copper imbalance in Alzheimer’s disease: Convergence of the chemistry and the clinic. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2019, 397, 168-187, 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.06.018.

- Matthew Schrag; Claudius Mueller; Udochukwu Oyoyo; Mark A. Smith; Wolff M. Kirsch; Iron, zinc and copper in the Alzheimer's disease brain: A quantitative meta-analysis. Some insight on the influence of citation bias on scientific opinion. Progress in Neurobiology 2011, 94, 296-306, 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.05.001.

- Rosanna Squitti; Roberta Ghidoni; Ilaria Simonelli; Irena D. Ivanova; Nicola Antonio Colabufo; Massimo Zuin; Luisa Benussi; Giuliano Binetti; Emanuele Cassetta; Mauro Rongioletti; et al.Mariacristina Siotto Copper dyshomeostasis in Wilson disease and Alzheimer's disease as shown by serum and urine copper indicators. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 2018, 45, 181-188, 10.1016/j.jtemb.2017.11.005.

- Alan Rembach; Dominic J. Hare; Monica Lind; Christopher J. Fowler; Robert A. Cherny; Catriona McLean; Ashley I. Bush; Colin L. Masters; Blaine R. Roberts; Decreased Copper in Alzheimer's Disease Brain Is Predominantly in the Soluble Extractable Fraction. International Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2013, 2013, 1-7, 10.1155/2013/623241.

- Hiroyasu Akatsu; Akira Hori; Takayuki Yamamoto; Mari Yoshida; Maya Mimuro; Yoshio Hashizume; Ikuo Tooyama; Eric M. Yezdimer; Transition metal abnormalities in progressive dementias. BioMetals 2011, 25, 337-350, 10.1007/s10534-011-9504-8.

- Shino Magaki; Ravi Raghavan; Claudius Mueller; Kerby Oberg; Harry V. Vinters; Wolff M. Kirsch; Iron, copper, and iron regulatory protein 2 in Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Neuroscience Letters 2007, 418, 72-76, 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.077.

- Jingshu Xu; Paul Begley; Stephanie Church; Stefano Patassini; Selina McHarg; Nina Kureishy; Katherine A. Hollywood; Henry Waldvogel; Hong Liu; Shaoping Zhang; et al.Wanchang LinKarl HerholzClinton TurnerBeth J. SynekMaurice CurtisJack Rivers-AutyCatherine LawrenceKatherine KellettNigel HooperEmma R. L. C. VardyDonghai WuRichard UnwinRichard FaullAndrew DowseyGarth J. S. Cooper Elevation of brain glucose and polyol-pathway intermediates with accompanying brain-copper deficiency in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: metabolic basis for dementia. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 27524, 10.1038/srep27524.

- M.A Deibel; W.D Ehmann; W.R Markesbery; Copper, iron, and zinc imbalances in severely degenerated brain regions in Alzheimer's disease: possible relation to oxidative stress. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 1996, 143, 137-142, 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00203-1.

- Melissa Scholefield; Stephanie J. Church; Jingshu Xu; Stefano Patassini; Federico Roncaroli; Nigel M. Hooper; Richard D. Unwin; Garth J. S. Cooper; Widespread Decreases in Cerebral Copper Are Common to Parkinson's Disease Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease Dementia. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2021, 13, 3, 10.3389/fnagi.2021.641222.

- Simon A. James; Irene Volitakis; Paul A. Adlard; James A. Duce; Colin L. Masters; Robert A. Cherny; Ashley I. Bush; Elevated labile Cu is associated with oxidative pathology in Alzheimer disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2012, 52, 298-302, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.446.

- Sabrina Giacoppo; Maria Galuppo; Rocco Salvatore Calabrò; Giangaetano D’Aleo; Angela Marra; Edoardo Sessa; Daniel Giuseppe Bua; Angela Giorgia Potortì; Giacomo Dugo; Placido Bramanti; et al.Emanuela Mazzon Heavy Metals and Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Observational Study. Biological Trace Element Research 2014, 161, 151-160, 10.1007/s12011-014-0094-5.

- Soghra Bagheri; Rosanna Squitti; Thomas Haertlé; Mariacristina Siotto; Ali A. Saboury; Role of Copper in the Onset of Alzheimer’s Disease Compared to Other Metals. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2018, 9, 446, 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00446.

- Lu Wang; Ya-Ling Yin; Xin-Zi Liu; Peng Shen; Yan-Ge Zheng; Xin-Rui Lan; Cheng-Biao Lu; Jian-Zhi Wang; Current understanding of metal ions in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Translational Neurodegeneration 2020, 9, 1-13, 10.1186/s40035-020-00189-z.

- Maria Luisa Malosio; Franca Tecchio; Rosanna Squitti; Molecular mechanisms underlying copper function and toxicity in neurons and their possible therapeutic exploitation for Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 2021, 33, 2027-2030, 10.1007/s40520-019-01463-5.

- Justyna Dobrowolska-Iwanek; M. Dehnhardt; A. Matusch; M. Zoriy; Nicola Palomero-Gallagher; P. Kościelniak; Karl Zilles; J.S. Becker; Quantitative imaging of zinc, copper and lead in three distinct regions of the human brain by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Talanta 2008, 74, 717-723, 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.06.051.

- Ernesto Bonilla; Enrique Salazar; Jose Joaquin Villasmil; Ruddy Villalobos; Magaly Gonzalez; Jose Omar Davila; Copper distribution in the normal human brain. Neurochemical Research 1984, 9, 1543-1548, 10.1007/bf00964589.

- Jingshu Xu; Stephanie J. Church; Stefano Patassini; Paul Begley; Henry J. Waldvogel; Maurice A. Curtis; Richard L. M. Faull; Richard D. Unwin; Garth J. S. Cooper; Evidence for widespread, severe brain copper deficiency in Alzheimer's dementia. Metallomics 2017, 9, 1106-1119, 10.1039/c7mt00074j.

- Robert Ehehalt; Patrick Keller; Christian Haass; Christoph Thiele; Kai Simons; Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer β-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts. Journal of Cell Biology 2003, 160, 113-123, 10.1083/jcb.200207113.

- Jose Abad-Rodriguez; Maria Dolores Ledesma; Katleen Craessaerts; Simona Perga; Miguel Medina; Andre Delacourte; Colin Dingwall; Bart De Strooper; Carlos G. Dotti; Neuronal membrane cholesterol loss enhances amyloid peptide generation. Journal of Cell Biology 2004, 167, 953-960, 10.1083/jcb.200404149.

- Richard J. O'Brien; Philip C. Wong; Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing and Alzheimer's Disease. Annual Review of Neuroscience 2011, 34, 185-204, 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613.

- Katherine M. Davies; Dominic J. Hare; Veronica Cottam; Nicholas Chen; Leon Hilgers; Glenda Halliday; Julian F. B. Mercer; Kay L. Double; Localization of copper and copper transporters in the human brain. Metallomics 2013, 5, 43-51, 10.1039/c2mt20151h.

- Daryl E. Hartter; Ayalla Barnea; Evidence for release of copper in the brain: Depolarization-induced release of newly taken-up67copper. Synapse 1988, 2, 412-415, 10.1002/syn.890020408.

- Alexander Hopt; Stefan Korte; Herbert Fink; Ulrich Panne; Reinhard Niessner; Reinhard Jahn; Hans Kretzschmar; Jochen Herms; Methods for studying synaptosomal copper release. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2003, 128, 159-172, 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00173-0.

- Hye Jung Kim; Deepa Ajit; Troy S. Peterson; Yanfang Wang; Jean M. Camden; W. Gibson Wood; Grace Y. Sun; Laurie Erb; Michael Petris; Gary A. Weisman; et al. Nucleotides released from Aβ1-42-treated microglial cells increase cell migration and Aβ1-42 uptake through P2Y2 receptor activation. Journal of Neurochemistry 2012, 121, 228-238, 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07700.x.

- Zhiqiang Zheng; Carine White; Jaekwon Lee; Troy S. Peterson; Ashley I. Bush; Grace Y. Sun; Gary A. Weisman; Michael J. Petris; Altered microglial copper homeostasis in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry 2010, 114, 1630-1638, 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06888.x.

- Sumin Lee; Clive Yik-Sham Chung; Pei Liu; Laura Craciun; Yuki Nishikawa; Kevin J. Bruemmer; Itaru Hamachi; Kaoru Saijo; Evan W. Miller; Christopher J. Chang; et al. Activity-Based Sensing with a Metal-Directed Acyl Imidazole Strategy Reveals Cell Type-Dependent Pools of Labile Brain Copper. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2020, 142, 14993-15003, 10.1021/jacs.0c05727.

- Weihong He; Y. James Kang; Ischemia-induced Copper Loss and Suppression of Angiogenesis in the Pathogenesis of Myocardial Infarction. Cardiovascular Toxicology 2012, 13, 1-8, 10.1007/s12012-012-9174-y.

- Eduard Berenshtein; Bernd Mayer; Chaya Goldberg; Nahum Kitrossky; Mordechai Chevion; Patterns of Mobilization of Copper and Iron Following Myocardial Ischemia: Possible Predictive Criteria for Tissue Injury. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 1997, 29, 3025-3034, 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0535.

- Kui Li; Chen Li; Ying Xiao; Tao Wang; Y James Kang; Featured Article: The loss of copper is associated with the increase in copper metabolism MURR domain 1 in ischemic hearts of mice. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2018, 243, 780-785, 10.1177/1535370218773055.

- Ana Sanchez‐Perez; Marta Llansola; Omar Cauli; Vicente Felipo; Modulation of NMDA receptors in the cerebellum. II. Signaling pathways and physiological modulators regulating NMDA receptor function. The Cerebellum 2005, 4, 162-170, 10.1080/14734220510008003.

- Sharon A. Swanger; Katie M. Vance; Jean-François Pare; Florence Sotty; Karina Fog; Yoland Smith; Stephen F. Traynelis; NMDA Receptors Containing the GluN2D Subunit Control Neuronal Function in the Subthalamic Nucleus.. The Journal of Neuroscience 2015, 35, 15971-83, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1702-15.2015.

- Praseeda Mullasseril; Kasper Hansen; Katie M. Vance; Kevin Ogden; Hongjie Yuan; Natalie L. Kurtkaya; Rose Santangelo; Anna G. Orr; Phuong Le; Kimberly M. Vellano; et al.Dennis C. LiottaStephen F. Traynelis A subunit-selective potentiator of NR2C- and NR2D-containing NMDA receptors. Nature Communications 2010, 1, 1-8, 10.1038/ncomms1085.

- Marta Llansola; Ana Sanchez‐Perez; Omar Cauli; Vicente Felipo; Modulation of NMDA receptors in the cerebellum. 1. Properties of the NMDA receptor that modulate its function. The Cerebellum 2005, 4, 154-161, 10.1080/14734220510007996.

- Andrew J. Larner; The cerebellum in Alzheimer's disease.. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 1997, 8, 203-209, 10.1159/000106632.

- H. Braak; E. Braak; Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathologica 1991, 82, 239-259, 10.1007/bf00308809.

- Masashi Kitazawa; Heng-Wei Hsu; Rodrigo Medeiros; Copper Exposure Perturbs Brain Inflammatory Responses and Impairs Clearance of Amyloid-Beta. Toxicological Sciences 2016, 152, 194-204, 10.1093/toxsci/kfw081.

- Xiaofang Tan; Huifeng Guan; Yang Yang; Shenying Luo; Lina Hou; Hongzhuan Chen; Juan Li; Cu(II) disrupts autophagy-mediated lysosomal degradation of oligomeric Aβ in microglia via mTOR-TFEB pathway. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2020, 401, 115090, 10.1016/j.taap.2020.115090.

- Fengxiang Yu; Ping Gong; Zhuqin Hu; Yu Qiu; Yongyao Cui; Xiaoling Gao; Hongzhuan Chen; Juan Li; Cu(II) enhances the effect of Alzheimer’s amyloid-β peptide on microglial activation. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 122, 10.1186/s12974-015-0343-3.

- Carlo Condello; Peng Yuan; Aaron Schain; Jaime Grutzendler; Microglia constitute a barrier that prevents neurotoxic protofibrillar Aβ42 hotspots around plaques. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 1-14, 10.1038/ncomms7176.