Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Manuel Aureliano | + 2867 word(s) | 2867 | 2022-01-13 04:09:28 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -1 word(s) | 2866 | 2022-01-14 03:04:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Aureliano, M. Biomedical Applications of Polyoxometalates Environmental. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18221 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Aureliano M. Biomedical Applications of Polyoxometalates Environmental. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18221. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Aureliano, Manuel. "Biomedical Applications of Polyoxometalates Environmental" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18221 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Aureliano, M. (2022, January 13). Biomedical Applications of Polyoxometalates Environmental. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18221

Aureliano, Manuel. "Biomedical Applications of Polyoxometalates Environmental." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Polyoxometalates (POMs) are clusters of units of oxoanions of transition metals, such as Mo, W, V and Nb, that can be formed upon acidification of neutral solutions. Once formed, some POMs have shown to persist in solution, even in the neutral and basic pH range. These inorganic clusters, amenable of a variety of structures, have been studied in environmental, chemical, and industrial fields, having applications in catalysis and macromolecular crystallography, as well as applications in biomedicine, such as cancer, bacterial and viral infections, among others.

polyoxometalates

decavanadate

emergent pollutants

cancer

bacterial resistance

virus infection

1. Polyoxometalates against Emerging Health Pollutants

The behavior of humanity has a major impact on the release of organic and/or inorganic pollutants into the environment, and has a profound effect on our lives. In the 21st century, POMs have gained attention as efficient adsorbents and/or green catalysts, and have been used in the development of multifunctional POM materials that could, and can, solve environmental problems, such as water pollution [1][2][3]. Thus, POMs have been chosen as agents against emergent pollutants. In fact, about 10% (about 1100) of the total of the articles published within the word “polyoxometalate” (POM) (11,000) are studies associated with the environment. In a search on the Web of Science, about 850 articles about POM and degradation can be found, 650 for dyes, 202 for POM and pollutants, 135 for waste, 75 for industrial chemicals, and 70 for wastewater. A lower number of papers were found for POM and pesticides and antibiotics [4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. Herein, we describe examples of recent studies about POMs’ ability for the degradation of mainly antibiotics, pesticides, and plastics.

Erythromycin and others antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, and cefalexin, were also found in effluents and surface waters [13][14]. Ciprofloxacin and erythromycin, together with the macrolide azithromycin, clarithromycin, and the penicillin-type amoxicillin, were included in the surface water watch list under the European Water Framework Directive [14]. More recently, this report was actualized, and the antibacterials sulfamethaxazole and trimethoprim; the anti-fungals clotrimazole, flucozanole, and miconazole; the antidepressant venlafaxine; and the synthetic hormone norethisterone were all added to the 3rd water watch list [15].

POMs were described as a good choice for antibiotic degradation, thus reducing the pharmaceutical environmental impact. In fact, C3N4 nanosheet composites loaded with POMs efficiently remove ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, as well as others pollutants, such as bisphenol A [4][5]. Polyoxotungstates (decatungstate, W10) also showed the ability to decompose antibiotics, such as sulfasalazine (SSZ) and one of its human metabolites, sulfapyridine (SPD), with different specificities and rates [6]. W10 also has a role in the degradation of pesticides, for example, the ones used for plant growth, namely 2-(1-naphthyl)acetamide (NAD) [7]. A metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) composite of PW12@MFM was shown to display catalytic degradation of sulfamethazine [8]. Besides pharmaceutical drugs, POMs-incorporated frameworks were also found to have applications for the decontamination of dyes, phenolic compounds, and pesticides [9]. Polyoxometalate-based ionic liquid (POM-IL) was used also for the extraction of triazole pesticides, such as hexaconazole, triticonazole, and difenoconazole from aqueous samples [10].

2. Anticancer Activity of Polyoxometalates

As observed above regarding the bacterial studies, the number of studies about POMs with antitumor activities in the past 10 years also represents the majority of the POM anticancer studies: around 87% of all the papers in this field, since the first report by 1965 [16]. Similarly, POT and POMos studies together represent the majority (90%), whereas for POVs and PONbs, lower percentages can be found. In fact, more than 120 articles/papers have been published with POMos and polyoxotungstates POTs in antitumor studies [17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]. POMs in cancer therapy and diagnostics, their modes of action, and future perspectives were reviewed [32][33][34][35][36]. Here are examples of POMs’ anticancer effects and putative modes of action, particularly for POVs, for the last five years.

The decavanadate complex proved to exhibit anti-tumor activity against various cancer cell lines, including specific toxicity against human cancer cells, whereas normal human cells were not affected, even for high concentrations of the complex [26]. This complex presented IC50 values of 0.72 and 1.8 μM against the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (A549) and human breast adenocarcinoma cell line (MDA-MB-231), respectively. When V10 complex was compared to the antitumor drug cisplatin for its cytotoxicity, it exhibited lower cytotoxicity against A549 than cisplatin, whereas its IC50 for MDA-MB-231 cells was 1.7 μM against 700 μM of cisplatin, meaning that it is 400 times more effective. On the other hand, decavanadate alone also showed anticancer activity against HeLa, Hep-2, HepG2, and MDA-MB-231, inducing apoptosis as the process of cell death [26]. The anti-proliferation activity of another POV, V18, was observed to affect the cellular cycle, and to mediate the arrest of MCF-7 cells in the G2/M phase and induction of apoptosis, besides DNA-, BSA-, and HSA-binding [27]. POV studies were also performed with U-87 and human liver SMMC-7721 cancer cells, and cell cycle arrest, DNA damage, and apoptosis were observed [27][37].

Considering all the cancer POMs studies in recent years, only very few were performed in vivo [18][20][29][31][33]. In one of these studies, it was described that the degradability of an organic POMo, based in Mo6O18, is the key to inhibit human malignant glioma cells (U251), besides having the capacity to cross the blood brain barrier, pointing to a new type of anticancer agent [29]. Another recent study demonstrated the anti-tumor activity of an iron heptatungsten phosphate polyoxometalate complex, Na12H[Fe(HPW7O28)2] (IHTPO), against large cell lung cancer (NCi-H460), human hepatoma (HepG2), leukemia (K-562), and lung carcinoma (A549) in vitro, and against S180 sarcoma transplanted in mice in vivo [18]. Even the cytotoxic effects were only seen at higher concentrations, with IC50 values superior to 60 μM, and IHPTO proved to be more efficient against S180 sarcoma transplanted mice. It was concluded that even if this POT exhibited lower antitumor activity than the already approved chemotherapeutic drugs, such as cisplatin, the interesting part is that IHTPO activity might be correlated to an immunomodulatory activity [18].

In another in vivo study, Fu et al. synthesized an amphiphilic organic-inorganic hybrid POT, [(C16H33)2NCONH(CH2)3SiNaP5W29O110] (abbreviated Na-lipidP5W29), to improve biocompatibility, bioactivity, and biospecificity [20]. Basically, a long chain organoalkoxysilane lipid was grafted into a lacunary Preyssler-type, [NaP5W29O107]14− (abbreviated P5W29) in order to produce the desired complex. The hybrid POT, Na-lipidP5W29, was tested for its antitumor activity against human colorectal cancer cells (HT29), and the results were compared to the parental POT, P5W29, and to 5-FU. For all concentrations tested, Na-lipidP5W29 exhibited higher inhibitory rates than its parental POT and 5-FU. The cytotoxic effect of the studied POT was also tested against human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Finally, it was suggested that the higher antitumor effect of Na-lipidP5W29 was due to its higher capacity to penetrate the cell, since it can spontaneously assemble into a vesicle [20]. In vivo studies with a Keggin-type POT, [PW11O39]7− (abbreviatedPW11) were also performed against colorectal cancer [29]. To improve bioactivity, and decrease the toxicity effect of this POT, an organometallic derivative of PW11 was synthesized and encapsulated to form nanoparticles of PtIV-PW11-DSPE-PEG2000 (NPs). Results showed that these NPs were more efficient in inhibiting the growth of WT20 cancer cells, and treating human colorectal cancer in mice than cisplatin, pointing once again to a new strategy to fight against cancer [29].

Mechanisms of Action of Polyoxometalates against Cancer Cells

As described above regarding the effects of POMs on cancer cells, several effects were referred, such as cell cycle arrest, apoptosis cell death, and interactions with DNA, among other observations and/or suggestions. However, the multiple mechanisms of action of polyoxometalates as antitumor agents are not yet fully understood. Recently, POMs as anticancer agents were reviewed [32]. In this section, it will resume some of them.

Research is looking for new non-competitive inhibitors of protein kinases, such as the human protein kinase CK2 inhibitors that have already been designated as promising drug targets in cancers [38][39]. POMs, such as P2Mo18, have been described as non-competitive and potent CK2 inhibitors (IC50 = 5 nM); although, due to its instability, it was not possible to know if this POM was responsible for the observed effects [39]. Nevertheless, POMs represent non-classical kinase inhibitors with increasing interest. Recently, aquaporins were also described to be potential protein membrane targets for POTs [40]. Aquaporins (AQPs) were found to be overexpressed in tumors, making their inhibitors of particular interest as anticancer drugs [41]. POTs strongly affect AQP3 activity, and induce inhibition of melanoma cancer cell migration and growth, unveiling their potential as anticancer drugs against tumors, opening a new window in this field of research [40]. P-type ATPases play a crucial role in cellular ion homeostasis, and have been described as potential molecular targets for several types of compounds used in the treatment of ulcers, cancer, heart ischemic failure, among other diseases. Among these compounds, several POMs have been described as PMCA (plasmatic membrane calcium ATPase) and SERCA (sarco(endo)plasmatic membrane calcium ATPase) inhibitors, and the effects compare with other inorganic compounds, as well as with therapeutic drugs [42][43][44][45][46][47].

Decavanadate species, and POMs in general, were described as strong inhibitors of phosphatases, such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) [48][23]. Seven POTs were assessed for their inhibitory effect on alkaline phosphatases ALP, and as putative antitumor agents [48][23]. Abnormal levels of ALP in the serum are detected in cancer patients, since tumors are an abnormal cellular growth proliferating faster than normal cells, and thus, the inhibition of ALP will affect tumor cell metabolism and function. Three different POMs, P5W30, V10, and the Anderson-Evans type [TeW6O24]6− (abbreviated TeW6), with chitosan-encapsulated nanoassemblies were tested as anticancer agents on HeLa cells [49]. The maximum cytotoxicity against HeLa cells was observed for the compound chitosan-P5W30, which also has higher phosphatase inhibition. It was suggested, in both studies, that the POT with the largest number of tungsten and phosphorus atoms may provide the optimal interaction with the phosphatase [49][23]. Finally, disturbance of antioxidant systems is a plausible anticancer strategy once tumor cells have rapid growth and metastasis. It was found that PW9Cu concentrations that induced osteosarcoma cells death in vitro also increased ROS, and decreased the reduced gluthatione/oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) ratio in the cells [24]. Moreover, the cytotoxicity of the compound was prevented with the addition of GSH, suggesting that oxidative stress is a mechanism of POMs to induce cancer cell death [24].

3. Antiviral Activity of Polyoxometalates

The number of studies using POMs that address viral infection is comparatively lower than the ones found for cancer and bacteria. Nevertheless, and due to the SARS-CoV2 pandemic [50], the number of studies testing metallodrugs which include POMs for treatment of viral infection has increased in recent years [51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66]. Still, the studies performed so far in the past 10 years represent almost 50% of the total. Among the studies described, and since 1971 [67], the ones using POTs represent the major contribution in this field (75%). Herein, it summarized examples of POMs’ antiviral effects and putative modes of action in recent years, highlighting, as above, the in vivo studies.

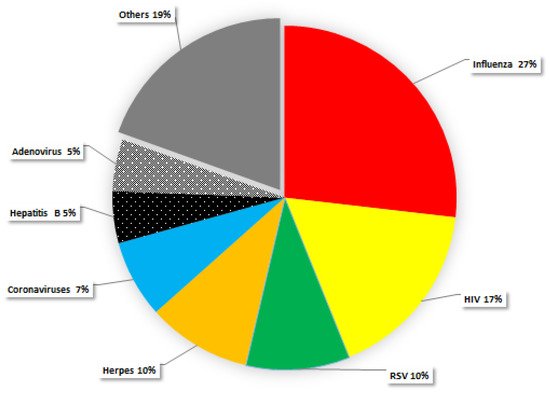

Considering all the POMs studies published on different types of viruses, it can be observed that influenza, HIV, herpes, and corona are the viruses most studied (Figure 1). Thus, the antiviral activity of POMs has been prevalent in respiratory tract viruses, mainly influenza viruses (Figure 1). A study with one Keggin-type POM, [SiVW11O40]5− (abbreviated SiVW11), and two double Keggin-type POMs, (K10Na[(VO)3(SbW9O33)2]) and (K11H[(VO)3(SbW9O33)2]), showed activity against dengue virus (DFV), influenza virus (FluV A), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza virus (PfluV 2), distemper virus (CDV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [55]. It was further demonstrated that (K10Na[(VO)3(SbW9O33)2]) strongly inhibits the binding of the viral gp120 antibodies [55]. P2W18 was also studied on influenza virus (FluV) in MDCK cell line [54]. It was suggested that P2W18 could inhibit the role hemagglutinin A (HA), responsible for the first stage of viral attachment [54]. Thus, the Wells–Dawson-type POM P2W18 is likely to have a dual mechanism of action in the inhibition of FluV replication: it reduces the binding of HA to the host cell membrane glycoprotein receptors, and impedes the fusion of viral particles into the cell [54].

Figure 1. Studies published with all types of POMs on different types of viruses (influenza, HIV, corona, herpes).

It is known that HIV specially targets CD4 molecules present in T lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophage lineage. It is also well-known that a glycoprotein, denominated gp120, allows it’s binding on CD4 cells, and, consequently, the injection of viral material into the host cell [61]. The activity against the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was demonstrated for some POTs [51][53][62]. It was suggested that POMs exhibited their antiviral effect by inhibiting the binding of virus to the host cell and/or its penetration [68][69][51][53]. For example, the single Wells–Dawson structure of the compound (α2-[NMe3H]7[CH3C5H4TiP2W17O61]), and the double Wells–Dawson of the structure compound (Na16[Mn4(H2O)2(P2W15O56)2]) both inhibited the binding of HIV particles to CD4 cells by blocking the binding of gp120 to SUP-T1 cells [53]. Other studies reported that POMs could inhibit proteases in a non-competitive manner at low micro molar concentrations [48][51][53], thus affecting virus infection.

As referred before for the cancer studies, in vivo POMs antiviral studies remain scarce, and very few studies [63][64] have been performed (Table 1). In this table, it compared the effects of two POTs and two clinically approved drugs in a mouse, the animal model. The Keggin-type POM[PW10Ti2O40]7− (abbreviated PW10Ti2) shows a survival rate (SR), indicating the percentage of mice that were still alive on day 14 after infection was 97%, for the treatment of HSV-2 virus infection when 25 mg/kg was administrated [63]. Higher survival rates of 90% were also observed upon a variant of influenza virus (FM1) infection for the POT Ce2H3[BW9VIW2VMn(H2O)O39] (abbreviated BW9VIW2VMn). However, 10 times of the amount administrated was needed to obtain the same rate of survival upon oral administration (100 mg/kg) in comparison with the intraperitoneal mode (10 mg/kg). Lower rates of SR were observed using well-known clinically approved drugs, such as acyclovir (anti-HSV agent) and ribavirin (broad-spectrum antiviral agent) [63][64]. For acyclovir, a 33% survival rate was observed for a 50 mg/kg administration upon HSV-2 virus infection, whereas for ribavirin, a 70% survival rate was obtained after a 200 mg/kg administration for the FM1 influenza virus infection (Table 1). In sum, when comparing the same mode of oral administration upon the same influenza virus infection for the clinically approved drug, ribavirin, and the new antiviral compound, BW9VIW2VMn, it clear that this POT has a higher SR (90% against 70%) for half of the dose administrated (100 mg/kg against 200 mg/kg).

Table 1. In vivo antiviral activity of POMs.

| Polyoxotungstates | Virus | Animal | Survival Rate (SR) | Dose (Mode of Administration) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K7[PW10Ti2O40] | HSV-2 | mouse | 97% | 25.0 mg/kg | [63] |

| Ce2H3[BW9VIW2VMn(H2O)O39] | FM1 | mouse | 90% | 100 mg/kg (o.a.) | [64] |

| Ce2H3[BW9VIW2VMn(H2O)O39] | FM1 | mouse | 90% | 10 mg/kg (i.p.) | [64] |

| Clinically approved drugs | |||||

| Acyclovir | HSV-2 | mouse | 33% | 50.0 mg/kg | [63] |

| Ribavirin | FM1 | mouse | 70% | 200 mg/kg (o.a) | [64] |

SR = survival rate, indicating the percentage of mice that were still alive on day 14 after infection; (o.a.) = oral administration; (i.p.) = intraperitoneal administration; FM1 = variant of influenza virus; HSV-2 = herpes simplex virus 2.

Mechanisms of Action of Polyoxometalates against Viral Infection

It was suggested that some POMs could inhibit the replication of HIV [51]. Certain POMs, such as Cs2K4Na[SiW9Nb3O40] (abbreviated SiW9Nb3O40), can act directly on hepatitis C virus (HCV) virion particles, and destabilize the integrity of its structure [64]. It was further suggested that POMs could specifically inhibit HCV infection at an early stage of its life cycle [52]. Note that the most cited paper regarding decavanadate (V10) in biology is the interaction of V10 in a spatially selective manner within the protein cages of virions [62]. Besides preventing the formation of virions, decavanadate is also able to inhibit viral activities by preventing the virus-cell host binding [62].

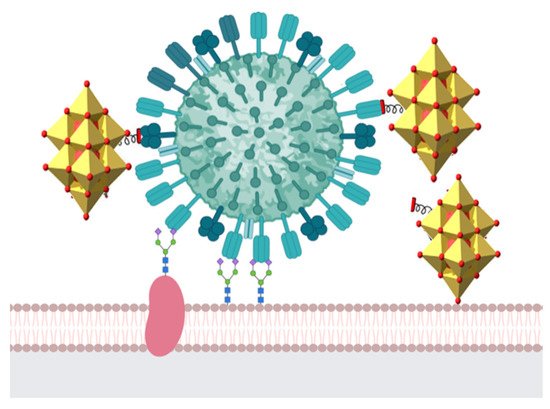

The inhibition of catalytic reactions promoted by sialyltransferases and sulfotransferases would affect the carbohydrate chains in glycoproteins that play a major part in cell–viral recognition, serving as a target for viral infections. Thus, by targeting virus membrane proteins, POMs would affect the early stage of viral infection. Moreover, some POMs are likely to have a dual mechanism of action in the inhibition of FluV replication: interacting with hemagglutinin A (HA), responsible for the first stage of viral attachment (Figure 2), and inhibiting the fusion of viral particles into the cell [59].

Figure 2. POM putative interactions with viral membrane proteins, such as hemagglutinin, preventing the early stage of infection. Moreover, interaction with neuraminidase would prevent a later stage of infection. Color code: glycoprotein, dark pink; hemagglutinin, dry green; neuraminidase, dark green; POM, yellow.

HIV is known to specially target CD4 molecules present in T lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophage lineage. A glycoprotein, denominated gp120, which is located on the surface of the virus, is the principal weapon of HIV because it allows its binding on CD4 cells, and the injection of the viral material into the cell [61]. Other studies reported that POMs could inhibit proteases in a non-competitive manner at low micro molar concentrations [48][51][53]. The HIV-1 protease is important for the maturation of protein components of an infectious HIV virion; thus, its inhibition could be responsible for the anti-HIV effect of POMs. For SARS-CoV, it was referred that POMs interact with the 3CLpro protein, affecting virus proliferation [65][66].

References

- Sivakumar, R.; Thomas, J.; Yoon, M. Polyoxometalate-Based Molecular/Nano Composites: Advances in Environmental Remediation by Photocatalysis and Biomimetic Approaches to Solar Energy Conversion. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2012, 13, 277–298.

- Omwoma, S.; Gore, C.T.; Ji, Y.; Hu, C.; Song, Y.F. Environmentally Benign Polyoxometalate Materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 286, 17–29.

- Lai, S.Y.; Ng, K.H.; Cheng, C.K.; Nur, H.; Nurhadi, M.; Arumugam, M. Photocatalytic Remediation of Organic Waste over Keggin-Based Polyoxometalate Materials: A Review. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128244.

- He, R.; Xue, K.; Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yang, T.; Hu, Y.; Wang, W. Nitrogen-deficient g-C3Nx/POMs porous nanosheets with P–N heterojunctions capable of the efficient photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127465.

- Shi, H.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, B.; Ji, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y. Fabrication of g-C3N4/PW12/TiO2 composite with significantly enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. J. Alloy. Compd. 2021, 860, 157924.

- Cheng, P.; Wang, Y.; Sarakha, M.; Mailhot, G. Enhancement of the photocatalytic activity of decatungstate, W10O324−, for the oxidation of sulfasalazine/sulfapyridine in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 404, 112890.

- Silva, E.S.D.; Sarakha, M.; Burrows, H.D.; Wong-Wah-Chung, P. Decatungstate anion as an efficient photocatalytic species for the transformation of the pesticide 2-(1-naphthyl)acetamide in aqueous solution. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2017, 334, 61–73.

- Li, G.; Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Gao, R.; Cheng, Y.; Hou, L.; Wang, Y. Solvent-free method to encapsulate polyoxometalate into metal-organic frameworks as efficient and recyclable photocatalyst for harmful sulfamethazine degrading in water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 245, 753–759.

- López, Y.C.; Viltres, H.; Gupta, N.K.; Acevedo-Peña, P.; Leyva, C.; Ghaffari, Y.; Gupta, A.; Kim, S.; Bae, J.; Kim, K.S. Transition metal-based metal–organic frameworks for environmental applications: A review. Env. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1295–1334.

- Majdafshar, M.; Piryaei, M.; Abolghasemi, M.M.; Rafiee, E. Polyoxometalate-based ionic liquid coating for solid phase microextraction of triazole pesticides in water samples. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1553–1559.

- Martinetto, Y.; Pegot, B.; Roch-Marchal, C.; Cottyn-Boitte, B.; Floquet, S. Designing functional polyoxometalate-based ionic liquid crystals and ionic liquids. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 228–247.

- Misra, A.; Zambrzycki, C.; Kloker, G.; Kotyrba, A.; Anjass, M.H.; Castillo, I.F.; Mitchell, S.G.; Güttel, R.; Streb, C. Water Purification and Microplastics Removal Using Magnetic Polyoxometalate-Supported Ionic Liquid Phases (magPOM-SILPs). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1601–1605.

- Sanseverino, I.; Navarro-Cuenca, A.; Loos, R.; Marinov, D.; Lettieri, T. State of the Art on the Contribution of Water to Antimicrobial Resistance; JRC Technical Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018.

- Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Vaz-Moreira, I.; Della Giustina, S.V.; Llorca, M.; Barceló, D.; Schubert, S.; Berendonk, T.U.; Michael-Kordatou, I.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Martinez, J.L.; et al. Antibiotic residues in final effluents of European wastewater treatment plants and their impact on the aquatic environment. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105733.

- Gomez Cortes, L.; Marinov, D.; Sanseverino, I.; Navarro-Cuenca, A.; Niegowska, M.; Porcel Rodriguez, E.; Lettieri, T. Selection of Substances for the 3rd Watch List under the Water Framework Directive; JRC Technical Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020.

- Mukherjee, H.N. Treatment of Cancer of the Intestinal Tract with a Complex Compound of Phosphotungstic Phosphomolybdic Acids and Caffeine. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 1965, 44, 477–479.

- Wang, L.; Yu, K.; Zhou, B.-B.; Su, Z.-H.; Gao, S.; Chu, L.-L.; Liu, J.-R.; Wang, L. The inhibitory effects of a new cobalt-based polyoxometalate on the growth of human cancer cells. Dalt. Trans. 2014, 43, 6070.

- Zhang, B.; Qiu, J.; Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z. Anti-tumor and immunomodulatory activity of iron hepta-tungsten phosphate oxygen clusters complex. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 293–301.

- Dianat, S.; Bordbar, A.K.; Tangestaninejad, S.; Yadollahi, B.; Zarkesh-Esfahani, S.H.; Habibi, P. ctDNA binding affinity and in vitro antitumor activity of three Keggin type polyoxotungstates. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2013, 124, 27–33.

- Fu, L.; Gao, H.; Yan, M.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Dai, Z.; Liu, S. Polyoxometalate-Based Organic-Inorganic Hybrids as Antitumor Drugs. Small 2015, 11, 2938–2945.

- Bâlici, Ş.; Şuşman, S.; Rusu, D.; Nicula, G.Z.; Soriţău, O.; Rusu, M.; Biris, A.S.; Matei, H. Differentiation of stem cells into insulin-producing cells under the influence of nanostructural polyoxometalates. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2016, 36, 373–384.

- Dong, Z.; Tan, R.; Cao, J.; Yang, Y.; Kong, C.; Du, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Huang, B.; et al. Discovery of polyoxometalate-based HDAC inhibitors with profound anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2477–2484.

- Raza, R.; Matin, A.; Sarwar, S.; Barsukova-Stuckart, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Kortz, U.; Iqbal, J. Polyoxometalates as potent and selective inhibitors of alkaline phosphatases with profound anticancer and amoebicidal activities. Dalt. Trans. 2012, 41, 14329.

- León, I.E.; Porro, V.; Astrada, S.; Egusquiza, M.G.; Cabello, C.I.; Bollati-Fogolin, M.; Etchevery, S.B. Polyoxometalates as antitumor agents: Bioactivity of a new polyoxometalate with copper on a human osteosarcoma model. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2014, 222, 87–96.

- She, S.; Bian, S.; Huo, R.; Chen, K.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hao, J.; Wei, Y. Degradable Organically-Derivatized Polyoxometalate with Enhanced Activity against Glioblastoma Cell Line. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33529.

- Cheng, M.; Li, N.; Wang, N.; Hu, K.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, P.; Wei, Y. Synthesis, structure and antitumor studies of a novel decavanadate complex with a wavelike two-dimensional network. Polyhedron 2018, 155, 313–319.

- Qi, W.; Zhang, B.; Qi, Y.; Guo, S.; Tian, R.; Sun, J.; Zhao, M. The Anti-Proliferation Activity and Mechanism of Action of K12.6H2O on Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Molecules 2018, 22, 1535.

- Zheng, Y.; Gan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Self-Assembly and Antitumor Activity of a Polyoxovanadate-Based Coordination Nanocage. Chem. A Eur. J. 2019, 25, 15326–15332.

- Sun, T.; Cui, W.; Yan, M.; Qin, G.; Guo, W.; Gu, H.; Liu, S.; Wu, Q. Target Delivery of a Novel Antitumor Organoplatinum(IV)-Substituted Polyoxometalate Complex for Safer and More Effective Colorectal Cancer Therapy in vivo. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 7397–7404.

- Dong, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lu, J.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Y. HDAC inhibitor PAC-320 induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 512–523.

- Yong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gu, Z.; Du, J.; Guo, Z.; Dong, X.; Xie, J.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y. Polyoxometalate-Based Radiosensitization Platform for Treating Hypoxic Tumors by Attenuating Radioresistance and Enhancing Radiation Response. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 7164–7176.

- Bijelic, A.; Aureliano, M.; Rompel, A. Polyoxometalates as Potential Next-Generation Metallodrugs in the Combat against Cancer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 2980–2999.

- Boulmier, A.; Feng, X.; Oms, O.; Mialane, P.; Rivière, E.; Shin, C.J.; Yao, J.; Kubo, T.; Furuta, T.; Oldfield, E.; et al. Anticancer Activity of Polyoxometalate-Bisphosphonate Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, in vitro and in vivo Results. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 7558–7565.

- Aureliano, M.; Gumerova, N.I.; Sciortino, G.; Garribba, E.; Rompel, A.; Crans, D.C. Polyoxovanadates with emerging biomedical activities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 447, 214143.

- Guedes, G.; Wang, S.; Santos, H.A.; Sousa, F.L. Polyoxometalate Composites in Cancer Therapy and Diagnostics. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 2121–2132.

- Guedes, G.; Wang, S.; Fontana, F.; Figueiredo, P.; Linden, J.; Correia, A.; Pinto, R.J.B.; Hietala, S.; Sousa, F.L.; Santos, H.A. Dual-Crosslinked Dynamic Hydrogel Incorporating with pH and NIR Responsiveness for Chemo-Photothermal Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007761.

- Karimian, D.; Yadollahi, B.; Mirkhani, V. Dual functional hybrid-polyoxometalate as a new approach for multidrug delivery. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 247, 23–30.

- Nienberg, C.; Garmann, C.; Gratz, A.; Bollacke, A.; Götz, C.; Jose, J. Identification of a Potent Allosteric Inhibitor of Human Protein Kinase CK2 by Bacterial Surface Display Library Screening. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 6.

- Prudent, R.; Moucadel, V.; Laudet, B.; Barette, C.; Lafanechère, L.; Hasenknopf, B.; Li, J.; Bareyt, S.; Lacote, E.; Thorimbert, S.; et al. Identification of Polyoxometalates as Nanomolar Noncompetitive Inhibitors of Protein Kinase CK2. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 683–692.

- Pimpão, C.; da Silva, I.V.; Mósca, A.F.; Pinho, J.O.; Gaspar, M.M.; Gumerova, N.I.; Rompel, A.; Aureliano, M.; Soveral, G. The aquaporin-3-inhibiting potential of polyoxotungstates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2467.

- Soveral, G.; Casini, A. Aquaporin modulators: A patent review (2010–2015). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016, 27, 49–62.

- Fraqueza, G.; Ohlin, C.A.; Casey, W.H.; Aureliano, M. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase interactions with decaniobate, decavanadate, vanadate, tungstate and molybdate. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 107, 82–89.

- Fraqueza, G.; Carvalho, L.A.; de Marques, E.B.; Marques, M.P.M.; Maia, L.; Ohlin, C.A.; Casey, W.H.; Aureliano, M. Decavanadate, decaniobate, tungstate and molybdate interactions with sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase: Quercetin prevents cysteine oxidation by vanadate but does not reverse ATPase inhibition. Dalt. Trans. 2012, 41, 12749.

- Gumerova, N.; Krivosudský, L.; Fraqueza, G.; Breibeck, J.; Al-Sayed, E.; Tanuhadi, E.; Bijelic, A.; Fuentes, J.; Aureliano, M.; Rompel, A. The P-type ATPase inhibiting potential of polyoxotungstates. Metallomics 2018, 10, 287–295.

- Fraqueza, G.; Fuentes, J.; Krivosudský, L.; Dutta, S.; Mal, S.S.; Roller, A.; Giester, G.; Rompel, A.; Aureliano, M. Inhibition of Na+/K+- and Ca2+-ATPase activities by phosphotetradecavanadate. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 197, 110700.

- Fonseca, C.; Fraqueza, G.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Aureliano, M. The Ca2+-ATPase inhibition potential of gold (I,III) compounds. Inorganics 2020, 8, 49.

- Berrocal, M.; Cordoba-Granados, J.J.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Gutierrez-Merino, C.; Aureliano, M.; Mata, A.M. Gold Compounds Inhibit the Ca2+-ATPase Activity of Brain PMCA and Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells and Decrease Cell Viability. Metals 2021, 11, 1934.

- Lee, S.Y.; Fiene, A.; Li, W.; Hanck, T.; Brylev, K.A.; Fedorov, V.E.; Lecka, J.; Haider, A.; Pietzsch, H.J.; Zimmermann, H.; et al. Polyoxometalates—Potent and selective ecto-nucleotidase inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 171–181.

- Saeed, S.H.; Al-Oweini, R.; Haider, A.; Kortz, U.; Iqbal, J. Cytotoxicity and enzyme inhibition studies of polyoxometalates and their chitosan nanoassemblies. Toxicol. Rep. 2014, 1, 341–352.

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733.

- Flütsch, A.; Schroeder, T.; Grütter, M.G.; Patzke, G.R. HIV-1 protease inhibition potential of functionalized polyoxometalates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 1162–1166.

- Qi, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Qi, Y.; Li, J.; Niu, J.; Zhong, J. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus infection by polyoxometalates. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 392–398.

- Witvrouw, M.; Weigold, H.; Pannecouque, C.; Schols, D.; De Clercq, E.; Holan, G. Potent anti-HIV (type 1 and type 2) activity of polyoxometalates: Structure-activity relationship and mechanism of action. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 778–783.

- Francese, R.; Civra, A.; Rittà, M.; Donalisio, M.; Argenziano, M.; Cavalli, R.; Mougharbel, A.; Kortz, U.; Lembo, D. Anti-zika virus activity of polyoxometalates. Antivir. Res. 2019, 163, 29–33.

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, K.; Qi, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Wang, E.; Wu, Z.; Kan, G.Z. Broad-spectrum antiviral property of polyoxometalate localized on a cell surface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 9785–9789.

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Zeng, Y. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry by a keggin polyoxometalate. Viruses 2018, 10, 265.

- Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Qi, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Niu, J. Antiviral effects of a niobium-substituted heteropolytungstate on hepatitis B virus-transgenic mice. Drug Dev. Res. 2019, 80, 1062–1070.

- Zhang, H.; Qi, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Chi, X.; Li, J.; Niu, J. Synthesis, characterization and biological activity of a niobium-substituted-heteropolytungstate on hepatitis B virus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 1664–1669.

- Hosseini, S.M.; Amini, E.; Kheiri, M.T.; Mehrbod, P.; Shahidi, M.; Zabihi, E. Anti-influenza Activity of a Novel Polyoxometalate Derivative (POM-4960). Int. J. Mol. Cell. Med. 2012, 1, 21–29.

- Shigeta, S.; Mori, S.; Yamase, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Yamamoto, N. Anti-RNA virus activity of polyoxometalates. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2006, 60, 211–219.

- Chanh, C.T.; Dreesman, G.R.; Kennedy, R.C. Monoclonal anti-idiotypic antibody mimics the CD4 receptor and binds human immunodeficiency virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 3891–3895.

- Douglas, T.; Young, M. Host-guest encapsulation of materials by assembled virus protein cages. Nature 1998, 393, 152–155.

- Yamase, T. Polyoxometalates Active against Tumors, Viruses, and Bacteria. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 2013, 54, 65–116.

- Liu, J.; Mei, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, E.; Ji, L.; Tao, P. Antiviral Activity of Mixed-Valence Rare Earth Borotungstate Heteropoly Blues against Influenza Virus in Mice. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2000, 11, 367–372.

- Shao, C.; Wang, J.-P.; Yang, G.-C.; Su, Z.-M.; Hu, D.-H.; Sun, C.-C. Interactions of 2− and its derivatives substituted with organic groups inhibitor with SARS-CoV 3CLpro by molecular modeling. Gaodeng Xuexiao Huaxue Xuebao/Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2008, 29, 165–169.

- Hu, D.; Shao, C.; Guan, W.; Su, Z.; Sun, J. Studies on the interactions of Ti-containing polyoxometalates (POMs) with SARS-CoV 3CLpro by molecular modeling. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007, 101, 89–94.

- Raynaud, M.; Chermann, J.C.; Plata, F.; Mathé, G. Inhibitors of viruses of the leukemia and murine sarcoma group. Biological inhibitor CJMR. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Seances L’academie des Sci. Ser. D 1971, 272, 2038–2040.

- Inoue, M.; Segawa, K.; Matsunaga, S.; Matsumoto, N.; Oda, M.; Yamase, T. Antibacterial activity of highly negative charged polyoxotungstates, K27 and K18, and Keggin-structural polyoxotungstates against Helicobacter pylori. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005, 99, 1023–1031.

- Inoue, M.; Suzuki, T.; Fujita, Y.; Oda, M.; Matsumoto, N.; Yamase, T. Enhancement of antibacterial activity of beta-lactam antibiotics by P2W18O62]6-, 4-, and 7− against methicillin-resistant and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006, 100, 1225–1233.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No