Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luca Cucullo | + 2804 word(s) | 2804 | 2021-11-12 04:28:08 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 2804 | 2022-01-14 02:15:36 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 2804 | 2022-03-28 04:49:16 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Cucullo, L. Protective Role of NRF2. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18216 (accessed on 13 January 2026).

Cucullo L. Protective Role of NRF2. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18216. Accessed January 13, 2026.

Cucullo, Luca. "Protective Role of NRF2" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18216 (accessed January 13, 2026).

Cucullo, L. (2022, January 13). Protective Role of NRF2. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18216

Cucullo, Luca. "Protective Role of NRF2." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (NRF2) is the major modulator of the xenobiotic-activated receptor (XAR) and is accountable for activating the antioxidative response elements (ARE)-pathway modulating the detoxification and antioxidative responses of the cells.

NRF2

cerebrovascular

neurodegenerative

1. NRF2 Regulation and Response to Oxidative Stress

Domain analysis by high-resolution crystal structure and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy has shown that the molecular structure of NRF2 includes seven functional domains (Neh1–Neh7) that regulate its transcriptional activity and stability [1]. The first conserved domain, Neh1, containing basic bZIP motif binds, to the ARE sequence exposing a nuclear localization signal required for translocation of released NRF2 from Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) into the nucleus [2][3][4]. Neh1 and Neh2 play differing roles with respect to NRF2 regulation. While Neh1 modulates NRF2 protein stability through interaction with the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, Neh2, a negative regulatory domain located in the N-terminal region, promotes NRF2 ubiquitination followed by proteasomal degradation, which is a result of increased KEAP1–NRF2 binding [5]. While Neh3 (which is located in the carboxyl-terminal region of the protein) modulates the transcriptional activation of the ARE genes [1][6], the Neh4 and Neh5 domains play a cooperative role in facilitating NRF2 transcription by binding to a transcriptional co-activator [7] and also increases NRF2–ARE gene expression by interfacing with the nuclear cofactor RAC3/AIB1/SRC-3 [7][8]. The Neh6 and Neh7 domains control KEAP1-independent degradation of NRF2 and regulate the activity of NRF2 so that KEAP1-alternative pathway of NRF2 degradation arises based on the recognition of phosphorylated Neh6 by the E3 ligase adapter beta-TrCP [9][10][11] and Neh7 inhibits NRF2 via interaction with retinoid X receptor α [12]. The main step in detoxification is the nuclear and cytoplasmic disposition of NRF2 so that under basal conditions, NRF2 is rapidly polyubiquitinated while cellular redox homeostasis is sustained by the accumulation of the NRF2 in the nucleus to mediate the normal expression of ARE-dependent genes [13][14].

KEAP1, the main intracellular regulator of NRF2, is composed of three main domains (totaling 624 amino acids) including the Broad-complex (1), Tramtrack (2), and the Bric-a-Brac (BTB) domain (3) which includes a cysteine-rich region and a double glycine repeat -DGR- binding site between KEAP1 and NRF2. Several cysteine residues within the BTB domain act as OS sensors and/or inducer ligands within the cell’s environment [1]. The activity of the NRF2–ARE signaling pathway is controlled by degradation and sequestration of NRF2 in the cytoplasm through binding with KEAP1 [15][13]. Other factors including post-transcription changes, gene polymorphisms in the promoter region, and protein–protein interactions are also influenced by NRF2 basal activity [14][16]. It is noteworthy that in response to mitochondrial oxidative stressors NRF2 provides direct interaction with the mitochondrial membrane [17].

Under basal conditions, KEAP1 binds to NRF2 in the cytoplasm and enhances the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of NRF2, whereas in response to oxidative stress condition, the NRF2 DLG motif is released from the DGR domain in KEAP1, which then undergoes conformational changes and dissociate NRF2 from itself to shift into the nucleus freely [14]. Independently from KEAP1 activity, not only phosphorylation of NRF2’s serine enhance separation of NRF2 from KEAP1 [13], but also glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), synthesis of specific microRNAs, methylation of CpG islands, histone phosphorylation, and acetylation modulate the expression and activation of NRF2 [18][19][20][21]. This cytoprotective pathway encompasses detoxification systems such as oxidation/reduction factors (Phase I), conjugation enzymes (Phase II), and drug efflux transporters (Phase III) [14][21]. NRF2 also controls/enhances the expression of active efflux transporters that remove or keep out potentially detrimental endogenous or xenobiotics of the cell [14] as well as tight junction (TJ) expression and BBB integrity at the neurovascular unit [22]. NRF2 nuclear accumulation can also have harmful effects [3] which accounts for the necessity of autoregulating the cellular levels of NRF2 [6][23]. For this end, the cullin3/ring box 1 (Cul3/Rbx1) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex promotes polyubiquitination of NRF2 coupled with KEAP 1 followed by NRF2 proteasomal degradation. This mechanism controls the “switching off” of NRF2-activated gene expression in the nucleus [6].

2. Role of NRF2 in Aging and Traumatic Brain Injury

Non-effective antioxidative responses to excessive ROS production and changes in redox signaling playing are one of the major reasons for advanced aging, whereas the inability to properly counteract OS leads to the progressive accumulation of OS-induced cellular damage [24][25]. Recent studies have, in fact, shown that age-related OS damages are dependent upon decreased antioxidant responses, as well as proteasome reduction, and reduced efficiency of mitochondrial proteases. The resulting effect of this impaired antioxidative response and inability to effectively maintain the redox balance is an accumulation of intracellular and intramitochondrial aggregates of oxidized proteins [26]. Similarly, the decreased level NADPH and GSH with aging could likely be due to a decreased cellular antioxidative capacity, as well as reduced intake of dietary antioxidants. Although there is a lot of dispute over the effect of age on the basal expression levels of antioxidative response factors, it seems that the primary underlying cause is a reduced NRF2 activity [27][28][29].

In respect to traumatic brain injury (TBI), disruption in the normal brain function following TBI is one of the foremost causes of death as well as severe emotional, physical, and cognitive impairments [30][31][32]. In spite of the pathogenic role of the primary brain injury immediate to TBI, the post-traumatic secondary injury derived from OS, inflammation, excitotoxicity, enhanced vascular permeability, and BBB impairment can significantly worsen post-traumatic brain damage as well as clinical outcomes [33][34]. Excessive ROS generation following cell damage, neuronal cell death, and brain dysfunction are the results of several secondary biochemical and metabolic changes in the cells [35]. According to recent studies, NRF2 plays a neuroprotective role in TBI so that NRF2 activation counteracts TBI-induced OS, loss of BBB integrity, etc. Unsurprisingly, impairments of the NRF2–ARE pathway leading to reduced activity of this protective system can result in more extensive post-TBI tissue damage, thus aggravating the secondary injury and worsening outcome. Accordingly, promoting upregulation of NRF2 activity could be exploited to reduce post-traumatic brain injuries, improve clinical outcomes, and reduce the risk of additional neurological disorders [36][37].

3. Ischemic Stroke and Protective Role of NRF2

Stroke, the fifth leading cause of death in the United States and a major cause of permanent disability, is defined by a bursting or blockage of blood vessels resulting in the sudden interruption of the local blood supply and the initiation of an anoxic and hypoglycemic state in the affected brain tissue [38]. Moreover, neuronal cell membrane depolarization causes the release of the neurotransmitter glutamate, which is the activator of the ionotropic glutamate receptor N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) [15]. The resulting opening of these non-selective cation channels leads to calcium overload and neuronal cell death [39]. These events are associated with excessive ROS production by the mitochondria which overwhelm the antioxidant defenses, leading to post-ischemic inflammation and enhanced brain tissue damage [40][41][42][43]. Furthermore, degradation of the structural proteins of the vascular wall and loss of BBB integrity also occur as a result of blood flow restoration, which suddenly enhances tissue oxygenation further exacerbating ROS production, inflammatory responses, and OS damage [15]. Adhesion of leukocytes across the blood vessels and transmigration into the brain parenchyma is facilitated by the concurrent expression of vascular adhesion molecules on the luminal surface of the vascular walls. Based on these premises, it is evident that control of ROS levels and OS prevention could be a potential therapeutic strategy to address post-ischemic secondary brain injury and improve stroke outcome [15][44][45][46]. Recent studies demonstrated that the protective effect of interactions between p62 and the NRF2–EpRE signaling pathway inhibited OS damage during cerebral ischemia/ reperfusion in rat undergoing transient middle artery occlusion (tMCAO) and also promoted NRF2 activity to lower the infarct volume and post-ischemic neurocognitive impairments [47][48]. NRF2 activity is also crucial to protect the brain against injury. In fact, NRF2 activation through the use of pharmacological enhancers improved neuronal cell viability, decreased BBB permeability, and promoted the transcription of cytoprotective genes [49][50]. Furthermore, enhanced infarct size, inflammatory damages, and neurological deficits were reported in NRF2 KO mice when compared to controls (wild-type mice). By contrast to controls, the use of NRF2 enhancer in knock out mice did not elicit any beneficial effect [51]. Most recently, other studies have shown that NRF2 downregulated the activity of the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome by acting on thioredoxin-1 (Trx1)/thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP) complex [44]. The NLRP3 inflammasome plays a key role in inflammation damage in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting the activity of interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis which contributes to the ischemic reperfusion damage at the CNS [52]. The activation of NLRP3 is dependent upon the interaction with TXNIP, which dissociates from the Trx1/TXNIP complex under OS. Thus, it is clear how targeting NRF2 represent a viable target for the treatment of ischemia and reperfusion injury.

4. Role of NRF2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases

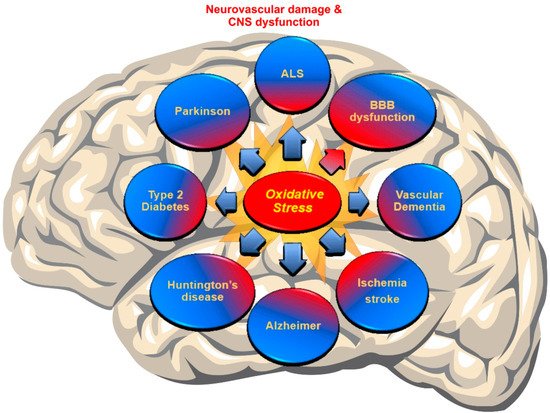

Recent discoveries have mentioned OS as a major pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders (NDDs) due to the accumulation of ROS [38][53]. In fact, a failure in maintaining the proper balance between ROS generation and their neutralization causes a disruption of brain homeostasis leading to neurodegenerative disorders [54][55] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the Cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases associated with impaired redox metabolism and oxidative stress.

Alzheimer’s disease: A neuropathological hallmark of AD is the formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and extracellular senile plaques (SPs) composed of small Aβ peptides [56]. Several studies propose that OS is an early prodromal event for progressive neurodegenerative disorders [57]. According to several studies on AD, NRF2 was able to provide a neuroprotective effect by decreasing ROS generation and ROS-induced toxicity mediated by Aβ [58][59]. Supporting data have shown that NRF2 activators, such as sulforaphane (SFN) lower toxin-induced Aβ1-42 secretion, while enhancing cell viability and improving cognitive function [60][61]. These beneficial effects may be due to the formation of Aβ aggregates or the inhibition of the release of monomer/oligomeric Aβ from dead cells [62]. A recent study also outlined the role of NRF2 in facilitating autophagy as well as altering β-Amyloid precursor proteins (APP) and Aβ processing whereas NRF2 knockout APP/PS1 mice showed increased accumulation of insoluble APP fragments and Aβ as well as mammalian targets of rapamycin (mTOR) activity [15][63]. The investigators also found that overexpression of mitochondria catalase in APP transgenic mice (Tg2576), decreases the formation of full-length APPs and lowers soluble and insoluble Aβ levels. From a clinical perspective, this may translate into extending the lifespan of the patient while improving working memory [15]. In a recent study, Rojo et al. demonstrated the protective effect of NRF2 against exacerbation of astrogliosis and microgliosis using transgenic mouse models [62]. Specifically, the investigators have shown a reduction in homeostatic responses with aging along with NRF2 activity resulting in reduced protection against proteotoxic, inflammatory and oxidative stress stimuli [15][64].

Parkinson’s disease: PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by lowered dopamine levels in the striatum due to the loss of dopaminergic neurons located in the substantia nigra affecting movement [65]. The initial symptoms in PD patients sometimes are tremors affecting one hand or slowing of movement. With the progression of the disease controls over movement is completely compromised and the effects are extended to neurocognitive functions dementia [15]. The certain diagnosis of PD in both familial and sporadic PD patients is the presence of Lewy bodies (LBs) as abnormal protein aggregates developing inside nerve cells. The main constituent of LBs is Alpha-synuclein (αSyn) which is a small protein with 140 amino acids. αSyn is abundant in presynaptic nerve terminals playing a role in synaptic transmission and dopamine levels adjustment [15]. Recent studies strongly postulate the association between PD with abnormal ROS production promoted by the dopamine metabolism, excitatory amino acids and iron content [57]. Moreover, it is emphasized that this increased OS plays a pivotal role in αSyn proteostasis, whereas NRF2 activity can counteract αSyn production and the associated cellular damage [58][66][67][68][69]. Recently, NRF2 overexpression has not only confirmed the reduction of the generation of αSyn aggregates in the CNS [70], but also the activation of NRF2 has appeared to prevent the loss of dopaminergic neurons mediated by αSyn and the consequent impairment of motor functions [15][71]. NRF2 deficiency and promoted expression of αSyn experienced enhanced loss of dopaminergic neuron and increased neuroinflammation and protein aggregation, whereas the enhanced expression level of NRF2 in a mutant αSyn transgenic mouse model, provided neuroprotective effects [15][72][69].

Huntington’s disease: HD as an inherited neurodegenerative disease is characterized by the loss of GABAergic inhibitory spiny projection neurons in the striatum [65] due to abnormally elongated poly-glutamine (polyQ) stretch encoded by the atypical expansion of adenine, cytosine, and guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeats at the huntingtin protein (Htt). According to several in vitro studies, NRF2 activation can play a protective role in the reduction of mHtt-induced toxicity, while in HD patients the initiation of the NRF2–ARE system in striatal cells in response to OS failed because of the concurrent activation of the autophagy pathway [73][74]. Moreover, additional data have confirmed that Htt aggregation directly enhanced ROS generation promoting cell toxicity [75]. Furthermore, co-transfection of NRF2 with mHtt in primary striatal neurons, reduction of the mean lifetime of mHtt N-terminal fragments, and, subsequently, improvement of cell viability suggest that NRF2 is more likely to decrease mHtt -toxicity by negatively affecting its aggregation [76].

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: ALS is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by the loss of motor neurons in the ventral horn of the spinal cord and in the motor cortex. The disease leads to progressive motor weakness and loss of controls of voluntary movements [15][65]. Although, for more than two decades, the mutation of Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) was the only genetic aberration relevant to the initiation of familial ALS, recent studies have found more abnormalities associated with the onset of sporadic and non-SOD1 familial ALS, including a host of RNA/DNA-binding proteins such as the 43-kDa transactive response (TAR) DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) and the fused in sarcoma/translocated in liposarcoma (FUS/TLS) [15]. Several recent studies support that NRF2 activation plays a protective role against OS and cell death promoted by the SOD1 mutant protein so that glial NRF2 overexpression improves the survival of the spinal cord’s motor neurons and extends their viable lifespan [77][78]. Additional studies will be required to evaluate the impact of NRF2 on cellular proteostasis as well as other ALS-associated gene mutations and the effect of NRF2 stimulation on late-stage microglia activation to prevent OS.

7. Role of NRF2 in Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Integrity and Function

In the central nervous system, the vascular endothelium acquires a set of specific characteristics and functions that differ from other vascular beds [79]. This specialized endothelium, which forms the BBB, becomes a dynamic functional interface between the blood and the brain that strictly regulates the passage of substances, maintains the brain homeostasis, and protects the brain from pathogens as well as endogenous and xenobiotic substances [30]. According to numerous studies, there is a relationship between NRF2 and BBB relevant to cerebrovascular disorders, so that NRF2 signaling plays a neurovascular protective role in the conservation of the BBB and CNS [80][81][82][83]. With regard to BBB endothelium, it has been emphasized that NRF2 upregulates the expression of tight junctional proteins (TJ), promotes redox metabolic functions, and produces ATP with mitochondrial biogenesis [84][81][83][85]. In fact, recently published data from side by side experiments investigating the impact of electronic cigarettes (e-Cig) versus TS on mouse primary brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC) clearly showed that NRF2 was strongly activated by the resulting OS and promoted upregulation of its downstream signaling molecule NQO-1 [83], whereas NQO-1 exerts acute detoxification and cytoprotective functions. However, chronic exposure to these pro-oxidative stimuli ended up compromising NRF2 activity and that of its downstream effector NQO-1. These resulted in an overall impairment of BBB integrity associated with increased permeability to paracellular markers and decreased trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) [45][83]. In addition to the loss of BBB integrity, in vivo data also showed upregulation of inflammatory markers including vascular adhesion molecules and pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as blood hemostasis changes favoring blood coagulation and, therefore, risk of stroke. Recent preliminary data and work by others have also clearly demonstrated that NRF2 modulates mitochondrial biogenesis, redox metabolism, and antioxidant/detoxification functions, thus, strongly suggesting that impairment of NRF2 activity can negatively affect mitochondrial biogenesis and function [84]. Altogether, these studies have shown that NRF2 plays a major role in critical BBB cellular functions ranging from modulation of barrier integrity, inflammatory responses, redox metabolism, and antioxidative responses [38][15][18][21][27][50][62][82][83][86][87]. In fact, cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative disorders such as subarachnoid brain hemorrhage, MS, ALS, AD, PD, stroke, and type-2 diabetes mellitus (TD2M) have been tied to dysfunctions of NRF2 activity [18][81][88][82][89][90][91][92][93]. Unsurprisingly, the activation of the NRF2–ARE system can potentially prevent/reduce the BBB impairments and, consequently, decrease some types of brain injury [94]. Since vascular endothelial dysfunction and consequent CNS damages have been relevant to ROS [95][96][97] and OS-driven inflammation [98], NRF2 activation is likely to preserve the BBB by maintaining ROS homeostasis that ultimately leads to a decrease in the risk of cerebrovascular, neurodegenerative, and CNS disorders [47][94][99][100][101]. For instance, the well-known NRF2 promoter/activator Sulforaphane (SFN) has been shown to have neuroprotective characteristics that counteract oxidative stress by enhancing NRF2 activation [88][94][102][103][104][105][106][107][108][109] and regulating antioxidant reactions [110].

References

- Cardozo, L.F.; Pedruzzi, L.M.; Stenvinkel, P.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; Daleprane, J.B.; Leite Jr, M.; Mafra, D. Nutritional strategies to modulate inflammation and oxidative stress pathways via activation of the master antioxidant switch Nrf2. Biochimie 2013, 95, 1525–1533.

- Baird, L.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. The cytoprotective role of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway. Arch. Toxicol. 2011, 85, 241–272.

- Cominacini, L.; Mozzini, C.; Garbin, U.; Pasini, A.; Stranieri, C.; Solani, E.; Vallerio, P.; Tinelli, I.A.; Pasini, A.F. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and Nrf2 signaling in cardiovascular diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 233–242.

- Bellezza, I.; Giambanco, I.; Minelli, A.; Donato, R. Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 721–733.

- Plafker, K.S.; Nguyen, L.; Barneche, M.; Mirza, S.; Crawford, D.F.; Plafker, S.M. The ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, UbcM2, can regulate the stability and activity of the anti-oxidant transcription factor, Nrf2. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 23064–23074.

- Niture, S.K.; Khatri, R.; Jaiswal, A.K. Regulation of Nrf2—An update. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 66, 36–44.

- Xiang, M.; Namani, A.; Wu, S.; Wang, X. Nrf2: bane or blessing in cancer? J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 140, 1251–1259.

- Krajka-Kuźniak, V.; Paluszczak, J.; Baer-Dubowska, W. The Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway: an update on its regulation and possible role in cancer prevention and treatment. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017, 69, 393–402.

- Rada, P.; Rojo, A.I.; Chowdhry, S.; McMahon, M.; Hayes, J.D.; Cuadrado, A. SCF/-TrCP promotes glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor in a Keap1-independent manner. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 31, 1121–1133.

- Rada, P.; Rojo, A.I.; Evrard-Todeschi, N.; Innamorato, N.G.; Cotte, A.; Jaworski, T.; Tobon-Velasco, J.C.; Devijver, H.; Garcia-Mayoral, M.F.; Van Leuven, F.; et al. Structural and functional characterization of Nrf2 degradation by the glycogen synthase kinase 3/beta-TrCP axis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 3486–3499.

- Chowdhry, S.; Zhang, Y.; McMahon, M.; Sutherland, C.; Cuadrado, A.; Hayes, J.D. Nrf2 is controlled by two distinct beta-TrCP recognition motifs in its Neh6 domain, one of which can be modulated by GSK-3 activity. Oncogene 2013, 32, 3765–3781.

- Bai, X.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.; Huang, M.; Jin, J. Emerging role of NRF2 in chemoresistance by regulating drug-metabolizing enzymes and efflux transporters. Drug Metab. Rev. 2016, 48, 541–567.

- Vomhof-DeKrey, E.E.; Picklo Sr, M.J. The Nrf2-antioxidant response element pathway: a target for regulating energy metabolism. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1201–1206.

- Naik, P.; Cucullo, L. Pathobiology of tobacco smoking and neurovascular disorders: untied strings and alternative products. Fluids Barriers CNS 2015, 12, 25.

- Sivandzade, F.; Prasad, S.; Bhalerao, A.; Cucullo, L. NRF2 and NF-κB interplay in cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative disorders: Molecular mechanisms and possible therapeutic approaches. Redox Biol. 2019, 21, 101059.

- Bryan, H.K.; Olayanju, A.; Goldring, C.E.; Park, B.K. The Nrf2 cell defence pathway: Keap1-dependent and-independent mechanisms of regulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 705–717.

- Strom, J.; Xu, B.; Tian, X.; Chen, Q.M. Nrf2 protects mitochondrial decay by oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 66–80.

- Sandberg, M.; Patil, J.; D’angelo, B.; Weber, S.G.; Mallard, C. NRF2-regulation in brain health and disease: implication of cerebral inflammation. Neuropharmacology 2014, 79, 298–306.

- Salazar, M.; Rojo, A.I.; Velasco, D.; de Sagarra, R.M.; Cuadrado, A. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibits the xenobiotic and antioxidant cell response by direct phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of the transcription factor Nrf2. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 14841–14851.

- Espada, S.; Rojo, A.I.; Salinas, M.; Cuadrado, A. The muscarinic M1 receptor activates Nrf2 through a signaling cascade that involves protein kinase C and inhibition of GSK-3beta: connecting neurotransmission with neuroprotection. J. Neurochem. 2009, 110, 1107–1119.

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 39, 199–218.

- Sajja, R.K.; Green, K.N.; Cucullo, L. Altered Nrf2 signaling mediates hypoglycemia-induced blood-brain barrier endothelial dysfunction in vitro. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122358.

- Niture, S.K.; Jain, A.K.; Shelton, P.M.; Jaiswal, A.K. Src subfamily kinases regulate nuclear export and degradation of transcription factor Nrf2 to switch off Nrf2-mediated antioxidant activation of cytoprotective gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 2048.

- Zhang, H.; Davies, K.J.; Forman, H.J. Oxidative stress response and Nrf2 signaling in aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 314–336.

- Sohal, R.S.; Orr, W.C. The redox stress hypothesis of aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 539–555.

- Ngo, J.K.; Pomatto, L.C.; Davies, K.J. Upregulation of the mitochondrial Lon Protease allows adaptation to acute oxidative stress but dysregulation is associated with chronic stress, disease, and aging. Redox Biol. 2013, 1, 258–264.

- Tarantini, S.; Valcarcel-Ares, M.N.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Tucsek, Z.; Hertelendy, P.; Kiss, T.; Gautam, T.; Zhang, X.A.; Sonntag, W.E.; de Cabo, R.; et al. Nrf2 Deficiency Exacerbates Obesity-Induced Oxidative Stress, Neurovascular Dysfunction, Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption, Neuroinflammation, Amyloidogenic Gene Expression, and Cognitive Decline in Mice, Mimicking the Aging Phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 853–863.

- Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Davies, K.J.; Sioutas, C.; Finch, C.E.; Morgan, T.E.; Forman, H.J. Nrf2-regulated phase II enzymes are induced by chronic ambient nanoparticle exposure in young mice with age-related impairments. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 2038–2046.

- Silva-Palacios, A.; Ostolga-Chavarria, M.; Zazueta, C.; Konigsberg, M. Nrf2: Molecular and epigenetic regulation during aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 31–40.

- Sivandzade, F.; Cucullo, L. In-vitro blood–brain barrier modeling: A review of modern and fast-advancing technologies. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 0271678X18788769.

- Hasan, A.; Deeb, G.; Rahal, R.; Atwi, K.; Mondello, S.; Marei, H.E.; Gali, A.; Sleiman, E. Mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 28.

- Semple, B.D.; Zamani, A.; Rayner, G.; Shultz, S.R.; Jones, N.C. Affective, neurocognitive and psychosocial disorders associated with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 123, 27–41.

- Dong, W.; Yang, B.; Wang, L.; Li, B.; Guo, X.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, J.; Pi, J.; Guan, D. Curcumin plays neuroprotective roles against traumatic brain injury partly via Nrf2 signaling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 346, 28–36.

- Angeloni, C.; Prata, C.; Vieceli Dalla Sega, F.; Piperno, R.; Hrelia, S. Traumatic brain injury and NADPH oxidase: a deep relationship. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015.

- Smith, J.A.; Park, S.; Krause, J.S.; Banik, N.L. Oxidative stress, DNA damage, and the telomeric complex as therapeutic targets in acute neurodegeneration. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 62, 764–775.

- He, Y.; Yan, H.; Ni, H.; Liang, W.; Jin, W. Expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 following traumatic brain injury in the human brain. Neuroreport 2019, 30, 344–349.

- Zhou, Y.; Tian, M.; Wang, H.D.; Gao, C.C.; Zhu, L.; Lin, Y.X.; Fang, J.; Ding, K. Activation of the Nrf2-ARE signal pathway after blast induced traumatic brain injury in mice. Int. J. Neurosci. 2019, 129, 801–807.

- Buendia, I.; Michalska, P.; Navarro, E.; Gameiro, I.; Egea, J.; León, R. Nrf2–ARE pathway: An emerging target against oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 157, 84–104.

- Suvanish Kumar, V.; Gopalakrishnan, A.; Naziroglu, M.; Rajanikant, G. Calcium ion–the key player in cerebral ischemia. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 2065–2075.

- Pradeep, H.; Diya, J.B.; Shashikumar, S.; Rajanikant, G.K. Oxidative stress–assassin behind the ischemic stroke. Folia Neuropathol. 2012, 50, 219–230.

- Stephenson, D.; Yin, T.; Smalstig, E.B.; Hsu, M.A.; Panetta, J.; Little, S.; Clemens, J. Transcription factor nuclear factor-κB is activated in neurons after focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2000, 20, 592–603.

- Kunz, A.; Abe, T.; Hochrainer, K.; Shimamura, M.; Anrather, J.; Racchumi, G.; Zhou, P.; Iadecola, C. Nuclear factor-κB activation and postischemic inflammation are suppressed in CD36-null mice after middle cerebral artery occlusion. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1649–1658.

- Harari, O.A.; Liao, J.K. NF-κB and innate immunity in ischemic stroke. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2010, 1207, 32–40.

- Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, Q.; Li, L.; Xie, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J. Nrf2 inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation through regulating Trx1/TXNIP complex in cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 336, 32–39.

- Kaisar, M.A.; Villalba, H.; Prasad, S.; Liles, T.; Sifat, A.E.; Sajja, R.K.; Abbruscato, T.J.; Cucullo, L. Offsetting the impact of smoking and e-cigarette vaping on the cerebrovascular system and stroke injury: Is Metformin a viable countermeasure? Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 353–362.

- Liu, L.; Locascio, L.M.; Dore, S. Critical Role of Nrf2 in Experimental Ischemic Stroke. Front. Pharm. 2019, 10, 153.

- Prasad, S.; Kaisar, M.A.; Cucullo, L. Unhealthy smokers: scopes for prophylactic intervention and clinical treatment. BMC Neurosci. 2017, 18, 70.

- Wang, W.; Kang, J.; Li, H.; Su, J.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y.; Yu, H.; Xiang, X.; Yi, H.; Lu, Y. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress in rat cortex by p62/ZIP through the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE signalling pathway after transient focal cerebral ischaemia. Brain Inj. 2013, 27, 924–933.

- Wang, B.; Zhu, X.; Kim, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, S.; Saleem, S.; Li, R.C.; Xu, Y.; Dore, S.; Cao, W. Histone deacetylase inhibition activates transcription factor Nrf2 and protects against cerebral ischemic damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 928–936.

- Zhao, J.; Moore, A.N.; Redell, J.B.; Dash, P.K. Enhancing expression of Nrf2-driven genes protects the blood brain barrier after brain injury. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 10240–10248.

- Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Cui, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Ji, H.; Du, Y. Ursolic acid promotes the neuroprotection by activating Nrf2 pathway after cerebral ischemia in mice. Brain Res. 2013, 1497, 32–39.

- Wang, H.; Zhong, D.; Chen, H.; Jin, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, G. NLRP3 inflammasome activates interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis during ischaemia-reperfusion injury in cerebral ischaemia in mice. Life Sci. 2019, 227, 101–113.

- Kaisar, M.A.; Sivandzade, F.; Bhalerao, A.; Cucullo, L. Conventional and electronic cigarettes dysregulate the expression of iron transporters and detoxifying enzymes at the brain vascular endothelium: In vivo evidence of a gender-specific cellular response to chronic cigarette smoke exposure. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 682, 1–9.

- Carvalho, C.; Machado, N.; Mota, P.C.; Correia, S.C.; Cardoso, S.; Santos, R.X.; Santos, M.S.; Oliveira, C.R.; Moreira, P.I. Type 2 diabetic and Alzheimer’s disease mice present similar behavioral, cognitive, and vascular anomalies. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 35, 623–635.

- Wevers, N.R.; de Vries, H.E. Morphogens and blood-brain barrier function in health and disease. Tissue Barriers 2016, 4, e1090524.

- De Strooper, B. Proteases and proteolysis in Alzheimer disease: a multifactorial view on the disease process. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 465–494.

- Freeman, L.R.; Keller, J.N. Oxidative stress and cerebral endothelial cells: Regulation of the blood–brain-barrier and antioxidant based interventions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1822, 822–829.

- Bae, E.-J.; Ho, D.-H.; Park, E.; Jung, J.W.; Cho, K.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, K.P.; Lee, S.-J. Lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal promotes seeding-capable oligomer formation and cell-to-cell transfer of α-synuclein. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2013, 18, 770–783.

- Li, X.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Lu, J.-M.; Tian, R.-B.; Wei, J. Allicin ameliorates cognitive deficits ageing-induced learning and memory deficits through enhancing of Nrf2 antioxidant signaling pathways. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 514, 46–50.

- Eftekharzadeh, B.; Maghsoudi, N.; Khodagholi, F. Stabilization of transcription factor Nrf2 by tBHQ prevents oxidative stress-induced amyloid β formation in NT2N neurons. Biochimie 2010, 92, 245–253.

- Kim, H.V.; Kim, H.Y.; Ehrlich, H.Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, Y. Amelioration of Alzheimer’s disease by neuroprotective effect of sulforaphane in animal model. Amyloid 2013, 20, 7–12.

- Rojo, A.I.; Pajares, M.; Garcia-Yague, A.J.; Buendia, I.; Van Leuven, F.; Yamamoto, M.; Lopez, M.G.; Cuadrado, A. Deficiency in the transcription factor NRF2 worsens inflammatory parameters in a mouse model with combined tauopathy and amyloidopathy. Redox Biol. 2018, 18, 173–180.

- Mao, P.; Manczak, M.; Calkins, M.J.; Truong, Q.; Reddy, T.P.; Reddy, A.P.; Shirendeb, U.; Lo, H.-H.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondria-targeted catalase reduces abnormal APP processing, amyloid β production and BACE1 in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: implications for neuroprotection and lifespan extension. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 2973–2990.

- Rojo, A.I.; Pajares, M.; Rada, P.; Nunez, A.; Nevado-Holgado, A.J.; Killik, R.; Van Leuven, F.; Ribe, E.; Lovestone, S.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. NRF2 deficiency replicates transcriptomic changes in Alzheimer’s patients and worsens APP and TAU pathology. Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 444–451.

- Gan, L.; Johnson, J.A. Oxidative damage and the Nrf2-ARE pathway in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis. Dis. 2014, 1842, 1208–1218.

- Näsström, T.; Fagerqvist, T.; Barbu, M.; Karlsson, M.; Nikolajeff, F.; Kasrayan, A.; Ekberg, M.; Lannfelt, L.; Ingelsson, M.; Bergström, J. The lipid peroxidation products 4-oxo-2-nonenal and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal promote the formation of α-synuclein oligomers with distinct biochemical, morphological, and functional properties. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 428–437.

- Lastres-Becker, I.; Garcia-Yague, A.J.; Scannevin, R.H.; Casarejos, M.J.; Kugler, S.; Rabano, A.; Cuadrado, A. Repurposing the NRF2 Activator Dimethyl Fumarate as Therapy Against Synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, 25, 61–77.

- Woo, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Moon, M.K.; Han, S.-H.; Yeon, S.K.; Choi, J.W.; Jang, B.K.; Song, H.J.; Kang, Y.G.; Kim, J.W. Discovery of vinyl sulfones as a novel class of neuroprotective agents toward Parkinson’s disease therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1473–1487.

- Gan, L.; Vargas, M.R.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Astrocyte-specific overexpression of Nrf2 delays motor pathology and synuclein aggregation throughout the CNS in the alpha-synuclein mutant (A53T) mouse model. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 17775–17787.

- He, Q.; Song, N.; Jia, F.; Xu, H.; Yu, X.; Xie, J.; Jiang, H. Role of α-synuclein aggregation and the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2/heme oxygenase-1 pathway in iron-induced neurotoxicity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 1019–1030.

- Barone, M.C.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Bohmann, D. Genetic activation of Nrf2 signaling is sufficient to ameliorate neurodegenerative phenotypes in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Dis. Models Mech. 2011, 4, 701–707.

- Innamorato, N.G.; Cuadrado, A.; Lastres-Becker, I.; Kirik, D.; Sahin, G.; Ulusoy, A.; Rábano, A. α-Synuclein expression and Nrf2 deficiency cooperate to aggravate protein aggregation, neuronal death and inflammation in early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 3173–3192.

- Jin, Y.N.; Yanxun, V.Y.; Gundemir, S.; Jo, C.; Cui, M.; Tieu, K.; Johnson, G.V. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and Nrf2 signaling contribute to compromised responses to oxidative stress in striatal cells expressing full-length mutant huntingtin. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57932.

- Stack, C.; Ho, D.; Wille, E.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Williams, C.; Liby, K.; Sporn, M.; Dumont, M.; Beal, M.F. Triterpenoids CDDO-ethyl amide and CDDO-trifluoroethyl amide improve the behavioral phenotype and brain pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 147–158.

- Hands, S.; Sajjad, M.U.; Newton, M.J.; Wyttenbach, A. In vitro and in vivo aggregation of a fragment of huntingtin protein directly causes free radical production. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44512–44520.

- Tsvetkov, A.S.; Arrasate, M.; Barmada, S.; Ando, D.M.; Sharma, P.; Shaby, B.A.; Finkbeiner, S. Proteostasis of polyglutamine varies among neurons and predicts neurodegeneration. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 586.

- Kanno, T.; Tanaka, K.; Yanagisawa, Y.; Yasutake, K.; Hadano, S.; Yoshii, F.; Hirayama, N.; Ikeda, J.-E. A novel small molecule, N-(4-(2-pyridyl)(1,3-thiazol-2-yl))-2-(2,4,6-trimethylphenoxy) acetamide, selectively protects against oxidative stress-induced cell death by activating the Nrf2–ARE pathway: Therapeutic implications for ALS. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 2028–2042.

- Mead, R.J.; Higginbottom, A.; Allen, S.P.; Kirby, J.; Bennett, E.; Barber, S.C.; Heath, P.R.; Coluccia, A.; Patel, N.; Gardner, I. S Apomorphine is a CNS penetrating activator of the Nrf2-ARE pathway with activity in mouse and patient fibroblast models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 61, 438–452.

- Liebner, S.; Czupalla, C.J.; Wolburg, H. Current concepts of blood-brain barrier development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2011, 55, 467–476.

- Sajja, R.K.; Prasad, S.; Tang, S.; Kaisar, M.A.; Cucullo, L. Blood-brain barrier disruption in diabetic mice is linked to Nrf2 signaling deficits: Role of ABCB10? Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 653, 152–158.

- Prasad, S.; Sajja, R.K.; Park, J.H.; Naik, P.; Kaisar, M.A.; Cucullo, L. Impact of cigarette smoke extract and hyperglycemic conditions on blood–brain barrier endothelial cells. Fluids Barriers CNS 2015, 12, 18.

- Alfieri, A.; Srivastava, S.; Siow, R.C.; Modo, M.; Fraser, P.A.; Mann, G.E. Targeting the Nrf2–Keap1 antioxidant defence pathway for neurovascular protection in stroke. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 4125–4136.

- Prasad, S.; Sajja, R.K.; Kaisar, M.A.; Park, J.H.; Villalba, H.; Liles, T.; Abbruscato, T.; Cucullo, L. Role of Nrf2 and protective effects of Metformin against tobacco smoke-induced cerebrovascular toxicity. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 58–69.

- Sajja, R.K.; Kaisar, M.A.; Vijay, V.; Desai, V.G.; Prasad, S.; Cucullo, L. In Vitro Modulation of Redox and Metabolism Interplay at the Brain Vascular Endothelium: Genomic and Proteomic Profiles of Sulforaphane Activity. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12708.

- Naik, P.; Sajja, R.K.; Prasad, S.; Cucullo, L. Effect of full flavor and denicotinized cigarettes exposure on the brain microvascular endothelium: a microarray-based gene expression study using a human immortalized BBB endothelial cell line. BMC Neurosci. 2015, 16, 38.

- Lu, X.-Y.; Wang, H.-D.; Xu, J.-G.; Ding, K.; Li, T. Deletion of Nrf2 exacerbates oxidative stress after traumatic brain injury in mice. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 35, 713–721.

- Wang, X.; Campos, C.R.; Peart, J.C.; Smith, L.K.; Boni, J.L.; Cannon, R.E.; Miller, D.S. Nrf2 upregulates ATP binding cassette transporter expression and activity at the blood–brain and blood–spinal cord barriers. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 8585–8593.

- Taguchi, K.; Fujikawa, N.; Komatsu, M.; Ishii, T.; Unno, M.; Akaike, T.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 degradation by autophagy for the maintenance of redox homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13561–13566.

- Chen, G.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Z. Role of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosci. Res. 2011, 89, 515–523.

- Petri, S.; Körner, S.; Kiaei, M. Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway: key mediator in oxidative stress and potential therapeutic target in ALS. Neurol. Res. Int. 2012, 2012.

- Lee, D.-H.; Gold, R.; Linker, R.A. Mechanisms of oxidative damage in multiple sclerosis and neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic modulation via fumaric acid esters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 11783–11803.

- Prasad, S.; Sajja, R.K.; Naik, P.; Cucullo, L. Diabetes mellitus and blood-brain barrier dysfunction: an overview. J. Pharmacovigil. 2014, 2, 125.

- Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Fang, H.; Wang, H.; Zang, H.; Xie, T.; Wang, W. Activation of Nrf2-ARE signal pathway protects the brain from damage induced by epileptic seizure. Brain Res. 2014, 1544, 54–61.

- Alfieri, A.; Srivastava, S.; Siow, R.C.; Cash, D.; Modo, M.; Duchen, M.R.; Fraser, P.A.; Williams, S.C.; Mann, G.E. Sulforaphane preconditioning of the Nrf2/HO-1 defense pathway protects the cerebral vasculature against blood–brain barrier disruption and neurological deficits in stroke. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 1012–1022.

- Patel, M. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Central Nervous System Disorders. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2016, 37, 768–778.

- Salim, S. Oxidative Stress and the Central Nervous System. J. Pharm. Exp. 2017, 360, 201–205.

- Yaribeygi, H.; Panahi, Y.; Javadi, B.; Sahebkar, A. The Underlying Role of Oxidative Stress in Neurodegeneration: A Mechanistic Review. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2018, 17, 207–215.

- Solleiro-Villavicencio, H.; Rivas-Arancibia, S. Effect of Chronic Oxidative Stress on Neuroinflammatory Response Mediated by CD4(+)T Cells in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2018, 12, 114.

- Chen, Z.; Mao, X.; Liu, A.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Ye, M.; Ye, J.; Liu, P.; Xu, S.; Liu, J. Osthole, a natural coumarin improves cognitive impairments and BBB dysfunction after transient global brain ischemia in C57 BL/6J mice: involvement of Nrf2 pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 186–194.

- Imai, T.; Takagi, T.; Kitashoji, A.; Yamauchi, K.; Shimazawa, M.; Hara, H. Nrf2 activator ameliorates hemorrhagic transformation in focal cerebral ischemia under warfarin anticoagulation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 89, 136–146.

- Li, W.; Suwanwela, N.C.; Patumraj, S. Curcumin by down-regulating NF-kB and elevating Nrf2, reduces brain edema and neurological dysfunction after cerebral I/R. Microvasc. Res. 2016, 106, 117–127.

- Tarozzi, A.; Angeloni, C.; Malaguti, M.; Morroni, F.; Hrelia, S.; Hrelia, P. Sulforaphane as a potential protective phytochemical against neurodegenerative diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 415078.

- Mao, L.; Yang, T.; Li, X.; Lei, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhang, F. Protective effects of sulforaphane in experimental vascular cognitive impairment: Contribution of the Nrf2 pathway. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 0271678X18764083.

- Soane, L.; Li Dai, W.; Fiskum, G.; Bambrick, L.L. Sulforaphane protects immature hippocampal neurons against death caused by exposure to hemin or to oxygen and glucose deprivation. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 88, 1355–1363.

- Yu, C.; He, Q.; Zheng, J.; Li, L.Y.; Hou, Y.H.; Song, F.Z. Sulforaphane improves outcomes and slows cerebral ischemic/reperfusion injury via inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 45, 74–78.

- Holloway, P.M.; Gillespie, S.; Becker, F.; Vital, S.A.; Nguyen, V.; Alexander, J.S.; Evans, P.C.; Gavins, F.N. Sulforaphane induces neurovascular protection against a systemic inflammatory challenge via both Nrf2-dependent and independent pathways. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2016, 85, 29–38.

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kostov, R.V. Glucosinolates and isothiocyanates in health and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 337–347.

- Zhao, X.; Wen, L.; Dong, M.; Lu, X. Sulforaphane activates the cerebral vascular Nrf2–ARE pathway and suppresses inflammation to attenuate cerebral vasospasm in rat with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Brain Res. 2016, 1653, 1–7.

- Takaya, K.; Suzuki, T.; Motohashi, H.; Onodera, K.; Satomi, S.; Kensler, T.W.; Yamamoto, M. Validation of the multiple sensor mechanism of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 817–827.

- Santín-Márquez, R.; Alarcón-Aguilar, A.; López-Diazguerrero, N.E.; Chondrogianni, N.; Königsberg, M. Sulfoaphane—Role in aging and neurodegeneration. GeroScience 2019, 1–16.

More

Information

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

802

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No