Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ichiro Ieiri | + 1726 word(s) | 1726 | 2021-12-29 07:07:06 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -2 word(s) | 1724 | 2022-01-13 03:50:13 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ieiri, I. Genetic Polymorphisms of Cathepsin A. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18172 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Ieiri I. Genetic Polymorphisms of Cathepsin A. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18172. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Ieiri, Ichiro. "Genetic Polymorphisms of Cathepsin A" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18172 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Ieiri, I. (2022, January 13). Genetic Polymorphisms of Cathepsin A. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18172

Ieiri, Ichiro. "Genetic Polymorphisms of Cathepsin A." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Cathepsin A (CatA) is important as a drug-metabolizing enzyme responsible for the activation of prodrugs, such as the anti-human immunodeficiency virus drug Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF).

cathepsin A

genetic polymorphisms

tenofovir alafenamide

1. Introduction

Prodrugs have played a very important role in drug development. Thirty-one of the 249 medicines approved by the Food and Drug Administration during the decade from 2017 to 2008 were pro-drugs. Nearly two prodrugs were approved each year during the decade except for 2016 [1]. The prodrugs were metabolized into active forms with pharmacological activity. Many metabolizing enzymes, such as carboxylesterase (CES), are involved in metabolic activation, and the effect of the polymorphism of these metabolizing enzymes on the drug metabolic activity is very important from the viewpoint of the appropriate use of the drug [2]. Cases in which the genetic polymorphism of the drug-metabolizing enzyme influenced the pharmacokinetics of the prodrug are shown below. Dabigatran etexilate, a prodrug with improved bioavailability of dabigatran, is activated by the hepatic drug-metabolizing enzyme CES1, and exhibits an antithrombin effect. Previous studies showed that patients with a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of CES1 had lower blood levels of dabigatran and a lower risk of bleeding as a side effect compared with the wild type [3]. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacological effects of tramadol, a known prodrug, were affected by cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) gene polymorphism. The effects of the variants in CYP2D6 were found to be attenuated in poor metabolizers (PM) and enhanced in ultrafast metabolizers (UM) [4]. The incidence of PM in the Japanese population is extremely low, at less than 1.0%, compared with that in Western populations (5~10%), suggesting that CYP2D6 genetic polymorphisms have a limited impact on the Japanese population [5]. Clopidogrel is a prodrug activated by CYP2C19, and CYP2C19 polymorphisms were reported to affect the metabolism of clopidogrel [6]. Eighteen to 22.5% of the Japanese population show decreased CYP2C19 activity, suggesting that the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel in the Japanese population varies among individuals [6][7]. There are large individual differences in the metabolic enzymes involved in the conversion of the prodrug to its active form. It is important for personalized drug therapy to identify genetic factors that contribute to individual differences in drug-metabolizing activity.

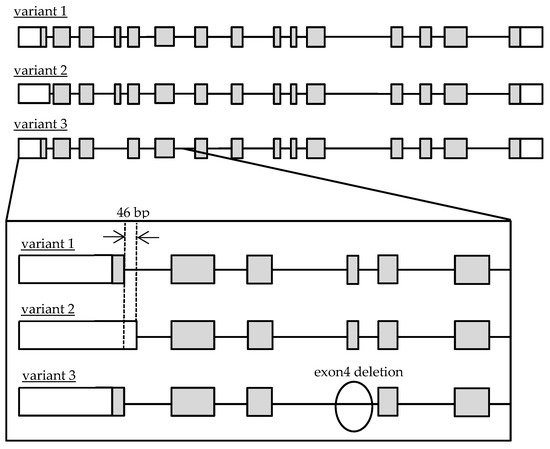

Recently, it was clarified that Cathepsin A (CatA) plays an important role in the metabolic activation of prodrugs such as Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF/GS-7340), which has been used in antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B and Sofosbuvir (SOF/GS-7977/PSI-7977) for hepatitis C virus [8][9]. The importance of CatA as a drug-metabolizing enzyme has been recognized in the research and development of drugs and appropriate use of medicine [8]. CatA is a multifunctional glycoprotein mainly distributed in lysosomes. CatA undergoes several steps to produce a mature protein. First, it is translated as a preprotein and transported to the endoplasmic reticulum, where the signal peptide is cleaved and an N-type sugar chain is added to form a 54-kDa precursor. Subsequently, an approximately 3-kDa polypeptide is removed and converted to mature 31 and 20-kDa forms [10]. CatA is widely expressed in the liver, kidney, and lung [11], and was also found in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) including CD4 + T cells that are HIV target cells [12]. CatA has a protective function such as the stabilization of β-galactosidase and activation of neuraminidase [13][14], and an enzyme function, such as acid carboxypeptidase, neutral esterase, and deamidase [15]. It was reported that an abnormality of CatA caused the galactosialidosis (GS) of autosomal recessive genetic disease, which is a type of lysosomal disease. To date, 36 mutations of the CatA gene have been reported [16]. Genetic analysis of the CatA gene in GS patients has been performed, but the frequency and function of the genetic polymorphisms in healthy adults have not been clarified. Three transcript variants of CatA were reported in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Reference Sequence Database (Refseq), but no major variants have been identified in humans [17][18]. The accession numbers are variant 1 (NM_000308.3 → NP_000299.2), variant 2 (NM_001127695.2 → NP_001121167.1), and variant 3 (NM_00116759.4.2 → NP_001161066.1). The gene structures are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of genomic Cathepsin A variant 1, 2 and 3 structures. Open and gray boxes represent untranslated and translated regions.

2. Quantification of Transcriptional Variants of CatA in Lymphocytes

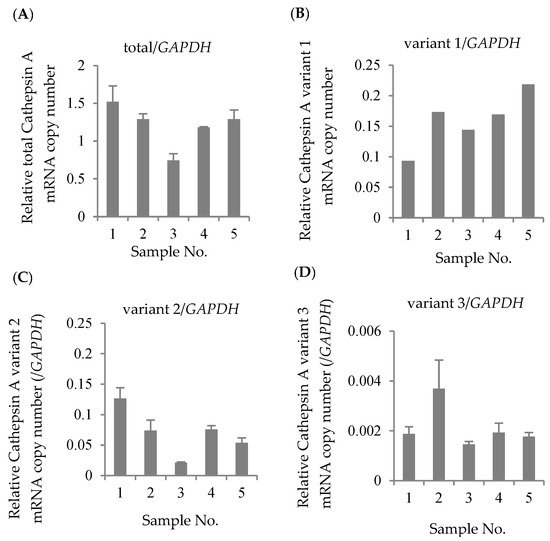

The mRNA expression levels of total CatA, variant 1, variant 2, and variant 3 were quantified by real-time PCR using 5 blood samples of healthy Japanese subjects. The housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal standard. As a result of absolute quantification, expressions of variants 1–3 were observed in all samples (Figure 2). The results showed that variants 1 and 2 were expressed at approximately the same level, and that the expression level of variant 3 was significantly lower than those variants. Thus, the major transcripts of CatA in human lymphocytes were suggested to be variants 1 and 2.

Figure 2. Absolute expression levels in Cathepsin A mRNA in Japanese lymphocytes. The copy numbers of total Cathepsin A variants (A), variant 1 (B), variant 2 (C), and variant 3 (D) were measured by real-time RT-PCR and were normalized by the copy number of GAPDH. The data represented as the mean ± S.D.

3. Genetic Polymorphism of CatA Gene

Genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood of 76 healthy Japanese subjects was used to investigate the genetic polymorphism of CatA. All 15 exons and 600 bp upstream of the translational start site (5′ FLR) of the human CatA gene, which has been reported to affect transcriptional activity [17], were analyzed. The genetic variants were screened by single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, and the sequence of the mutation was identified by the Dye Terminator method. As a result, nine genetic polymorphisms were identified (Table 3). Three of these polymorphisms were located in 5′ FLR, three were in the exon, and the other three were located in the intron. The mutation (85_87CTG>-) in exon 2 caused the deletion of leucine (Leu), resulting in the change of the leucine 9-repeat (Leu9) to 8-repeat (Leu8) in the signal peptide region. Homozygotes (Leu8/Leu8) for 85_87CTG>- were most frequent in 29 of 48 Japanese subjects, followed by heterozygotes (Leu9/Leu8) and the wild type (Leu9/Leu9). The haplotypes were estimated by Arlequin V.3.5 based on the identified genotypes, and five haplotypes were identified (Table 4).

Table 3. Cathepsin A genetic variations in healthy Japanese volunteers.

| Location | CDS Position * | Reference Number |

V/R Allele |

Amino Acid Substitution |

n | Number of | Frequency of Variant Allele (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R/R | V/R | V/V | |||||||

| Exon 1 | −322 | rs2868362 | G>A | - | 76 | 25 | 33 | 18 | 42.11 |

| −223 | rs117529875 | G>A | - | 76 | 74 | 2 | 0 | 1.32 | |

| −43 | rs116893852 | G>T | - | 76 | 54 | 19 | 3 | 16.45 | |

| Exon 2 | 85_87 | rs72555383 | CTG>- | 29 Leu >- | 48 | 2 | 17 | 29 | 78.13 |

| 108 | rs181943893 | G>C | Synonymous | 48 | 39 | 6 | 3 | 12.5 | |

| Exon 3 | 273 | rs742035 | C>G | Synonymous | 48 | 39 | 9 | 0 | 9.38 |

| Intron 9 | 924-19 | rs3215446 | C>- | - | 48 | 14 | 19 | 15 | 51.04 |

| Intron 10 | 1002 + 7 | rs2075961 | G>A | - | 48 | 0 | 13 | 35 | 86.46 |

| Intron 11 | 1142 + 10 | rs4608591 | C>T | - | 48 | 0 | 13 | 35 | 86.46 |

n = 48 or 76, CDS:coding sequence, R:reference allele, V:variant allele, * With respect to the translation start site of Cathepsin A gene; A in ATG is designated +1, Reference allele: Genbank accession no. NM_000308.4.

Table 4. Haplotypes of Cathepsin A 5′-FLR.

| Haplotype Pattern |

Genetic Variations | Estimated Frequency (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −322G>A | −223G>A | −43G>T | ||

| #1 | A | G | G | 45.4 |

| #2 | G | G | G | 37.0 |

| #3 | G | G | T | 16.3 |

| #4 | G | A | G | 1.18 |

| #5 | A | G | T | NE |

Estimated frequency was calculated by Arlequin V3.5. NE: Not estimated.

4. Effects of Polymorphisms of CatA Gene on Transcription Activity

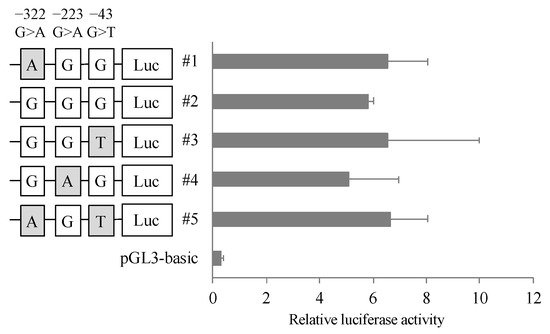

To clarify the effect of the variants in 5′ FLR on the transcriptional activity of the CatA gene, dual luciferase assays were performed. A reporter vector was constructed in which the 5′ FLR sequence of CatA was incorporated upstream of the luciferase gene of the pGL3-basic vector. Blood cell-derived K562 cells transfected with the reporter vector containing 5′ FLR showed higher transcriptional activity than the cells transfected with the control vector, but there was no significant difference in transcriptional activity between the five haplotypes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Reporter gene activities of Cathepsin A 5′-FLR. Luciferase reporter gene vectors containing each polymorphisms were transfected into the K562 cells. Relative luciferase activity of each reporter vector is Firefly luciferase activity normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. The data represented as mean + S.D. of triplicate experiments.

5. Effects of Polymorphism of CatA Gene on Protein Expression

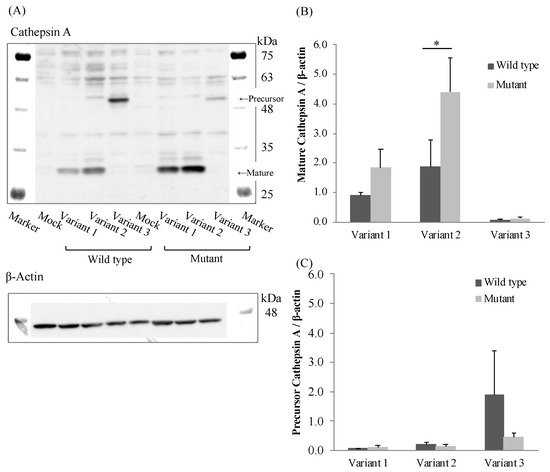

To evaluate the effect of the mutation (85_87CTG>-) in three transcriptional variants on CatA protein expression, we established CatA-stable expressing FLP-in 293 cells using the pcDNA5/FRT vector. CatA protein was quantified by Western blotting using protein extracted from the established cells (Figure 4A). As a result of comparing CatA protein expression levels among the variants, the expression level of mature CatA (31 kDa) tended to be higher in variant 2 than in variant 1 in all genotypes (Figure 4B). While variant 3 showed the strongest precursor CatA (54 kDa) expression among the variants, there was little expression of mature CatA. (Figure 4B,C). The expression of mature CatA in variant 2 was significantly higher in the mutant (Leu8) than in the wild type (Leu9) (p < 0.05) (Figure 4B). There was no significant effect of the mutant (Leu8) on the mature protein expression in variants 1 and 3. On the other hand, the expression level of the CatA precursor was not significantly affected by the mutant (Leu8) in any of the variants (Figure 4C). These results suggest that the mutation (85_87CTG>-) affects only the mature CatA in variant 2.

Figure 4. Western blotting analysis in stably Cathepsin A expressing Flp-in 293 cells. (A) Cathepsin A precursor, mature and β-actin. (B) Densitometric analysis was shown for precursor Cathepsin A/β-actin of the blots. (C) Densitometric analysis was shown for mature Cathepsin A/β-actin of the blots. The data represented as mean + S.D. of triplicate experiments. (t-test * p < 0.05).

6. Effects of Polymorphism of CatA on Metabolic Activity

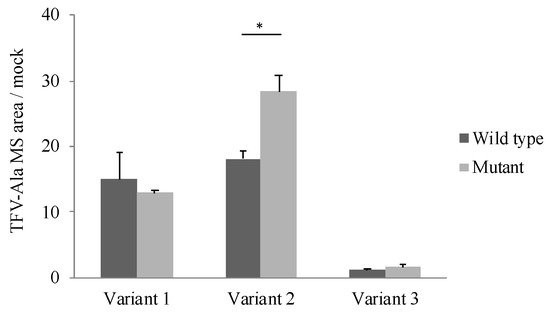

The effect of the polymorphism (85_87CTG>-) on CatA enzyme activity was examined. TAF, which has been reported as a specific substrate for CatA, was incubated for 60 min at a concentration of 5 μM in the cells stably expressing the CatA transcriptional variant with the polymorphism (85_87CTG>-). Tenofovir alanine (TFV-Ala), a metabolite of TAF, was measured by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometer (LC/MS/MS). In all variants, TFV-Ala was detected in CatA-stable expressing cells (Figure 5). The amount of TFV-Ala was markedly lower in the variant 3-transfected cells than that in variants 1 and 2. On the other hand, a significant increase in TFV-Ala was observed in variant 2 with the mutant (Leu8) compared with the wild type (Leu9) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Metabolism of TAF to TFV-Ala in stably Cathepsin A expressing Flp-in 293 cells. Cells were incubated with 5 µM TAF for 60 min. TFV-Ala in supernatants was quantified by LC-MS/MS. The data represented as mean + S.D. of triplicate experiments. (t-test * p < 0.05).

References

- Najjar, A.; Karaman, R. The prodrug approach in the era of drug design. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 1–5.

- Fukami, T.; Yokoi, T. The Emerging Role of Human Esterases. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2012, 27, 466–477.

- Paré, G.; Eriksson, N.; Lehr, T.; Connolly, S.; Eikelboom, J.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Axelxxon, T.; Haertter, S.; Oldgren, J.; Reilly, P.; et al. Genetic determinants of dabigatran plasma levels and their relation to bleeding. Circulation 2013, 127, 1404–1412.

- Crews, K.R.; Gaedigk, A.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Leeder, J.S.; Klein, T.E.; Caudle, K.E.; Haidar, C.E.; Shen, D.D.; Callaghan, J.T.; Sadhasivam, S.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy: 2014 update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 95, 376–382.

- Chida, M.; Yokoi, T.; Kosaka, Y.; Chiba, K.; Nakamura, H.; Ishizaki, T.; Yokota, J.; Kinoshita, M.; Sato, K.; Inaba, M.; et al. Genetic polymorphism of CYP2D6 in the Japanese population. Pharmacogenetics 1999, 9, 601–605.

- Kobayashi, M.; Kajiwara, M.; Hasegawa, S. A Randomized Study of the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacodynamics, and Pharmacokinetics of Clopidogrel in Three Different CYP2C19 Genotype Groups of Healthy Japanese Subjects. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2015, 22, 1186–1196.

- Furuta, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Shirai, N.; Ishizaki, T. CYP2C19 pharmacogenomics associated with therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastro-esophageal reflux diseases with a proton pump inhibitor. Pharmacogenomics 2007, 8, 1199–1210.

- Birkus, G.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Kutty, N.; MacArthur, H.; Cihlar, T.; Gibbs, C.; Swaminathan, S.; Lee, W.; McDermott, M.; et al. Cathepsin A is the major hydrolase catalyzing the intracellular hydrolysis of the antiretroviral nucleotide phosphonoamidate prodrugs GS-7340 and GS-9131. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 543–550.

- Murakami, E.; Tolstykh, T.; Bao, H.; Niu, C.; Steuer, H.M.; Bao, D.; Chang, W.; Espiritu, C.; Bansal, S.; Lam, A.M.; et al. Mechanism of activation of PSI-7851 and its diastereoisomer PSI-7977. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 34337–34347.

- Kolli, N.; Garman, S.C. Proteolytic activation of human cathepsin A. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 11592–11600.

- Satake, A.; Itoh, K.; Shimmoto, M.; Saido, T.C.; Sakuraba, H.; Suzuki, Y. Distribution of lysosomal protective protein in human tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 205, 38–43.

- Reich, M.; Spindler, K.D.; Burret, M.; Kalbacher, H.; Boehm, B.O.; Burster, T. Cathepsin A is expressed in primary human antigen-presenting cells. Immunol. Lett. 2010, 128, 143–147.

- Van Der Spoel, A.; Bonten, E.; d’Azzo, A. Transport of human lysosomal neuraminidase to mature lysosomes requires protective protein/cathepsin A. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 1588–1597.

- Morreau, H.; Galjart, N.J.; Willemsen, R.; Gillemans, N.; Zhou, X.Y.; d’Azzo, A. Human lysosomal protective protein. Glycosylation, intracellular transport, and association with β-galactosidase in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 17949–17956.

- Jackman, H.L.; Tan, F.L.; Tamei, C.; Beurling-Harbury, C.; Li, X.Y.; Skidgel, R.A.; Erdös, E.G. A peptidase in human Platelets that deamidates tachykinins. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 11265–11272.

- Nakajima, H.; Ueno, M.; Adachi, K.; Nanba, E.; Naria, A.; Tsukimoto, J.; Itoh, K.; Kawakami, A. A new heterozygous compound mutation in the CTSA gene in galactosialidosis. Hum. Genome Var. 2019, 6, 4–8.

- Rottier, R.J.; d’Azzo, A. Identification of the Promoters for the Human and Murine Protective Protein/Cathepsin A Genes. DNA Cell Biol. 1997, 16, 599–610.

- Galjart, N.J.; Gillemans, N.; Harris, A.; van der Horst, G.T.; Verheijen, F.W.; Galjaard, H.; d’Azzo, A. Expression of cDNA encoding the human “protective protein” associated with lysosomal β-galactosidase and neuraminidase: Homology to yeast proteases. Cell 1988, 54, 755–764.

More

Information

Subjects:

Allergy

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

694

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

13 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No