| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bahauddeen M. Alrfaei | + 2402 word(s) | 2402 | 2022-01-05 09:02:36 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2402 | 2022-01-13 06:54:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

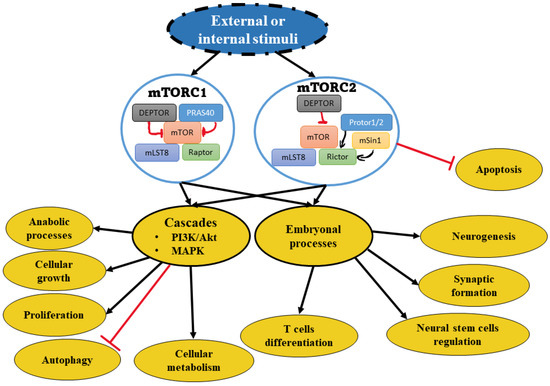

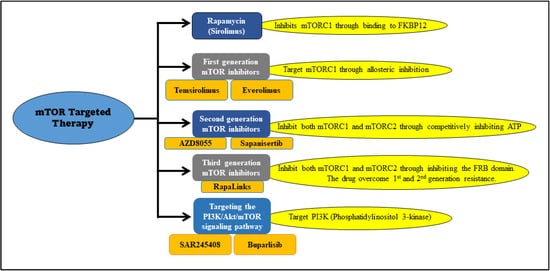

Medulloblastoma is a common fatal pediatric brain tumor. The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is one of the major pathways that have been activated during medulloblastoma development. It is a master regulator for signaling pathways that organize organismal development and homeostasis, because of its involvement in protein and lipid synthesis besides controlling the cell cycle and the cellular metabolism. mTOR inhibitors are a class of drugs that suppress the mTOR. In the clinic, they are primarily used as immunosuppressants and for the treatment of multiple cancers. Three generations of mTOR-targeted therapy have been developed to date. Resistance has been observed against mTOR inhibitor-targeted therapy in medulloblastoma.

1. mTOR Molecular Pathway

2. mTOR Involvement in Medulloblastoma

3. mTOR-Targeted Therapy in Medulloblastoma

| Drug | Target | Patients Groups | Medulloblastoma Cases/Total Tumor Cases |

Phase | Status/ Result | The National Clinical Trial Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sirolimus in combination with metronomic therapy |

mTOR | Children with recurrent or refractory solid and brain tumors |

2 / 18 | I | Complete/ well tolerated |

NCT01331135 |

| Everolimus | mTOR | Pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors | 3 / 41 | I | Complete/ well tolerated |

NCT00187174 |

| Temsirolimus | mTOR | Pediatric patients with recurrent/refractory solid tumors | 2 / 71 | I | Complete/ did not meet efficacy |

NCT00106353. |

| Temsirolimus in combination with irinotecan and temozolomide | mTOR | Children, adolescents, and young adults with relapsed or refractory solid tumors | 2 / 72 | I | Complete/ tolerated dose | NCT01141244 |

| Temsirolimus with perifosine | mTOR AKT |

Recurrent pediatric solid tumors |

2 / 23 | I | Complete/ tolerable toxicity | NCT01049841 |

| Vismodegib in combination with temozolomide versus temozolomide alone | Smo mTOR |

Patients with medulloblastomas with an activation of the Sonic hedgehog pathway | 24 / 24 | I II |

Terminated/ unclear |

NCT01601184 |

References

- Yang, H.; Rudge, D.G.; Koos, J.D.; Vaidialingam, B.; Yang, H.J.; Pavletich, N.P. mTOR Kinase Structure, Mechanism and Regulation by the Rapamycin-Binding Domain. Nature 2013, 497, 217–223.

- Jhanwar-Uniyal, M.; Wainwright, J.V.; Mohan, A.L.; Tobias, M.E.; Murali, R.; Gandhi, C.D.; Schmidt, M.H. Diverse Signaling Mechanisms of mTOR Complexes: MTORC1 and MTORC2 in Forming a Formidable Relationship. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2019, 72, 51–62.

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. MTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976.

- Yan, J.; Wang, R.; Horng, T. MTOR Is Key to T Cell Transdifferentiation. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 241–242.

- LiCausi, F.; Hartman, N.W. Role of mTOR Complexes in Neurogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1544.

- Huang, H.; Long, L.; Zhou, P.; Chapman, N.M.; Chi, H. MTOR Signaling at the Crossroads of Environmental Signals and T-Cell Fate Decisions. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 295, 15–38.

- Jaworski, J.; Spangler, S.; Seeburg, D.P.; Hoogenraad, C.C.; Sheng, M. Control of Dendritic Arborization by the Phosphoinositide-3′-kinase-akt-mammalian Target of Rapamycin Pathway. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 11300–11312.

- Bateup, H.S.; Takasaki, K.T.; Saulnier, J.L.; Denefrio, C.L.; Sabatini, B.L. Loss of tsc1 In Vivo Impairs Hippocampal Mglur-ltd and Increases Excitatory Synaptic Function. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 8862–8869.

- Murugan, A.K. MTOR: Role in Cancer, Metastasis and Drug Resistance. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 59, 92–111.

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Yang, C.; Lin, J. The Role of Shh Signalling Pathway in Central Nervous System Development and Related Diseases. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2021, 39, 180–189.

- Wu, C.-C.; Hou, S.; Orr, B.A.; Kuo, B.R.; Youn, Y.H.; Ong, T.; Roth, F.; Eberhart, C.G.; Robinson, G.W.; Solecki, D.J.; et al. MTORC1-Mediated Inhibition of 4EBP1 Is Essential for Hedgehog Signaling-Driven Translation and Medulloblastoma. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 673–688.

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, V.; McGuire, T.; Coulter, D.W.; Sharp, J.G.; Mahato, R.I. Challenges and Recent Advances in Medulloblastoma Therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 1061–1084.

- Bao, S.; Wu, Q.; McLendon, R.E.; Hao, Y.; Shi, Q.; Hjelmeland, A.B.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Bigner, D.D.; Rich, J.N. Glioma Stem Cells Promote Radioresistance by Preferential Activation of the DNA Damage Response. Nature 2006, 444, 756–760.

- Lineham, E.; Tizzard, G.J.; Coles, S.J.; Spencer, J.; Morley, S.J. Synergistic effects of inhibiting the mnk-eif4e and pi3k/akt/ mTOR pathways on cell migration in mda-mb-231 cells. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 14148–14159.

- Chaturvedi, N.K.; Kling, M.J.; Coulter, D.W.; McGuire, T.R.; Ray, S.; Kesherwani, V.; Joshi, S.S.; Sharp, J.G. Improved therapy for medulloblastoma: Targeting hedgehog and pi3k-mTOR signaling pathways in combination with chemotherapy. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16619.

- Dimitrova, V.; Arcaro, A. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Pathway in Medulloblastoma. Curr. Mol. Med. 2015, 15, 82–93.

- Robinson, G.; Parker, M.; Kranenburg, T.A.; Lu, C.; Chen, X.; Ding, L.; Phoenix, T.N.; Hedlund, E.; Wei, L.; Zhu, X.; et al. Novel Mutations Target Distinct Subgroups of Medulloblastoma. Nature 2012, 488, 43–48.

- Pei, Y.; Liu, K.-W.; Wang, J.; Garancher, A.; Tao, R.; Esparza, L.A.; Maier, D.L.; Udaka, Y.T.; Murad, N.; Morrissy, S.; et al. HDAC and PI3K Antagonists Cooperate to Inhibit Growth of MYC-Driven Medulloblastoma. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 311–323.

- Chaturvedi, N.K.; Kling, M.J.; Griggs, C.N.; Kesherwani, V.; Shukla, M.; McIntyre, E.M.; Ray, S.; Liu, Y.; McGuire, T.R.; Sharp, J.G. A novel Combination Approach Targeting an Enhanced Protein Synthesis Pathway in Myc-driven (group 3) Medulloblastoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 1351–1362.

- Aldaregia, J.; Odriozola, A.; Matheu, A.; Garcia, I. Targeting MTOR as a Therapeutic Approach in Medulloblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1838.

- Cavalli, F.M.G.; Remke, M.; Rampasek, L.; Peacock, J.; Shih, D.J.H.; Luu, B.; Garzia, L.; Torchia, J.; Nor, C.; Morrissy, A.S.; et al. Intertumoral Heterogeneity within Medulloblastoma Subgroups. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 737–754.

- Paul, R.; Bapat, P.; Deogharkar, A.; Kazi, S.; Singh, S.K.V.; Gupta, T.; Jalali, R.; Sridhar, E.; Moiyadi, A.; Shetty, P.; et al. MiR-592 Activates the MTOR Kinase, ERK1/ERK2 Kinase Signaling and Imparts Neuronal Differentiation Signature Characteristic of Group 4 Medulloblastoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, 2416–2428.

- Snuderl, M.; Batista, A.; Kirkpatrick, N.D.; de Almodovar, C.R.; Riedemann, L.; Walsh, E.C.; Anolik, R.; Huang, Y.; Martin, J.D.; Kamoun, W. Targeting Placental Growth Factor/neuropilin 1 Pathway Inhibits Growth and Spread of Medulloblastoma. Cell 2013, 152, 1065–1076.

- Sabers, C.J.; Martin, M.M.; Brunn, G.J.; Williams, J.M.; Dumont, F.J.; Wiederrecht, G.; Abraham, R.T. Isolation of a Protein Target of the FKBP12-Rapamycin Complex in Mammalian Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 815–822.

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. Research Progress of mTOR Inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 208, 112820.

- Meng, L.; Zheng, X.S. Toward Rapamycin Analog (Rapalog)-Based Precision Cancer Therapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 1163–1169.

- Mizuno, T.; Fukuda, T.; Christians, U.; Perentesis, J.P.; Fouladi, M.; Vinks, A.A. Population Pharmacokinetics of Temsirolimus and Sirolimus in Children with Recurrent Solid Tumours: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 1097.

- Qayed, M.; Cash, T.; Tighiouart, M.; MacDonald, T.J.; Goldsmith, K.C.; Tanos, R.; Kean, L.; Watkins, B.; Suessmuth, Y.; Wetmore, C.; et al. A phase i study of sirolimus in combination with metronomic therapy (choanome) in children with recurrent or refractory solid and brain tumors. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28134.

- Hudes, G.; Carducci, M.; Tomczak, P.; Dutcher, J.; Figlin, R.; Kapoor, A.; Staroslawska, E.; Sosman, J.; McDermott, D.; Bodrogi, I.; et al. Temsirolimus, Interferon Alfa, or Both for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 356, 2271–2281.

- Spunt, S.L.; Grupp, S.A.; Vik, T.A.; Santana, V.M.; Greenblatt, D.J.; Clancy, J.; Berkenblit, A.; Krygowski, M.; Ananthakrishnan, R.; Boni, J.P.; et al. Phase I Study of Temsirolimus in Pediatric Patients With Recurrent/Refractory Solid Tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2933.

- Bagatell, R.; Norris, R.; Ingle, A.; Ahern, C.; Voss, S.; Fox, E.; Little, A.; Weigel, B.; Adamson, P.; Blaney, S. Phase 1 Trial of Temsirolimus in Combination with Irinotecan and Temozolomide in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults with Relapsed or Refractory Solid Tumors: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 833–839.

- Becher, O.J.; Gilheeney, S.W.; Khakoo, Y.; Lyden, D.C.; Haque, S.; De Braganca, K.C.; Kolesar, J.M.; Huse, J.T.; Modak, S.; Wexler, L.H.; et al. A Phase I Study of Perifosine with Temsirolimus for Recurrent Pediatric Solid Tumors. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, 1–9.

- Gills, J.J.; Dennis, P.A. Perifosine: Update on a Novel Akt Inhibitor. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2009, 11, 102–110.

- Geoerger, B.; Kerr, K.; Tang, C.-B.; Fung, K.-M.; Powell, B.; Sutton, L.N.; Phillips, P.C.; Janss, A.J. Antitumor Activity of the Rapamycin Analog CCI-779 in Human Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor/Medulloblastoma Models as Single Agent and in Combination Chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1527–1532.

- Li, J.; Kim, S.G.; Blenis, J. Rapamycin: One Drug, Many Effects. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 373–379.

- Fouladi, M.; Laningham, F.; Wu, J.; O’Shaughnessy, M.A.; Molina, K.; Broniscer, A.; Spunt, S.L.; Luckett, I.; Stewart, C.F.; Houghton, P.J.; et al. Phase I Study of Everolimus in Pediatric Patients With Refractory Solid Tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 25, 4806–4812.

- Dancey, J.E. Therapeutic Targets: MTOR and Related Pathways. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006, 5, 1065–1073.

- Chresta, C.M.; Davies, B.R.; Hickson, I.; Harding, T.; Cosulich, S.; Critchlow, S.E.; Vincent, J.P.; Ellston, R.; Jones, D.; Sini, P.; et al. AZD8055 Is a Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable ATP-Competitive Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Kinase Inhibitor with In Vitro and In Vivo Antitumor Activity. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 288–298.

- Asahina, H.; Nokihara, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Yamada, Y.; Tamura, Y.; Honda, K.; Seki, Y.; Tanabe, Y.; Shimada, H.; Shi, X.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of AZD8055 in Japanese Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors; A Dose-Finding Phase i Study. Invest. New Drugs 2013, 31, 677–684.

- Houghton, P.J.; Gorlick, R.; Kolb, E.A.; Lock, R.; Carol, H.; Morton, C.L.; Keir, S.T.; Reynolds, C.P.; Kang, M.H.; Phelps, D.; et al. Initial Testing (Stage 1) of the mTOR Kinase Inhibitor AZD8055 by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2012, 58, 191–199.

- Kang, M.H.; Reynolds, C.P.; Maris, J.M.; Gorlick, R.; Kolb, E.A.; Lock, R.; Carol, H.; Keir, S.T.; Wu, J.; Lyalin, D.; et al. Initial Testing (Stage 1) of the Investigational MTOR Kinase Inhibitor MLN0128 by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 1486–1489.

- Rodrik-Outmezguine, V.S.; Okaniwa, M.; Yao, Z.; Novotny, C.J.; McWhirter, C.; Banaji, A.; Won, H.; Wong, W.; Berger, M.; de Stanchina, E.; et al. Overcoming MTOR Resistance Mutations with a New Generation MTOR Inhibitor. Nature 2016, 534, 272–276.

- Fan, Q.; Aksoy, O.; Wong, R.A.; Ilkhanizadeh, S.; Novotny, C.J.; Gustafson, W.C.; Truong, A.Y.-Q.; Cavanan, G.; Simonds, E.F.; Haas-Kogan, D.; et al. A Kinase Inhibitor Targeted to MTORC1 Drives Regression in Glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 424–435.