Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jarosław Nuszkiewicz | + 3114 word(s) | 3114 | 2022-01-07 04:14:03 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 3114 | 2022-01-12 01:59:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Nuszkiewicz, J. Physical Activity vs. Redox Balance in the Brain. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18056 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Nuszkiewicz J. Physical Activity vs. Redox Balance in the Brain. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18056. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Nuszkiewicz, Jarosław. "Physical Activity vs. Redox Balance in the Brain" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18056 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Nuszkiewicz, J. (2022, January 11). Physical Activity vs. Redox Balance in the Brain. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18056

Nuszkiewicz, Jarosław. "Physical Activity vs. Redox Balance in the Brain." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

It has been proven that physical exercise improves cognitive function and memory, has an analgesic and antidepressant effect, and delays the aging of the brain and the development of diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders. There are even attempts to use physical activity in the treatment of mental diseases. The course of most diseases is strictly associated with oxidative stress, which can be prevented or alleviated with regular exercise. It has been proven that physical exercise helps to maintain the oxidant–antioxidant balance.

physical exercise

oxidant–antioxidant equilibrium

central nervous system

neurodegeneration

exerkines

cognition

memory

1. The Influence of Physical Exercise on the Redox Balance

As early as over 40 years ago, the first studies appeared suggesting that physical exercise can lead to the distortion of the oxidant–antioxidant balance. The fact that oxidative stress occurs after PA is also confirmed by the most recent experimental work [1][2]. The main source of ROS in the organism during physical exertion is skeletal muscles. However, the contribution of other organs and tissues, such as heart, lungs or white blood cells, cannot be excluded [3]. The earlier studies considered mitochondria to be the dominant source of ROS in skeletal muscles and the enhanced generation of ROS was explained by the increase in oxygen consumption that accompanies increased activity of mitochondria during PA [3][4]. More recent studies, however, indicate that mitochondria produce higher levels of ROS in State 4 (basal state, nonphosphorylating conditions) compared to State 3 (active state, phosphorylating conditions) [5][6], which means that ROS generation in mitochondria of skeletal muscles decreases during PA. At the present state of knowledge, therefore, it is hard to determine unequivocally the contribution of mitochondria to ROS generation during physical exertion. Other sources of ROS in muscle fibres during physical exercises are NADPH oxidase, PLA2-dependent processes, and reactions catalysed by xanthine oxidase [7]. Which mechanism becomes the main source of ROS during the performed physical activity is probably dependent on the type of physical effort [8][9]. It can be, among others, aerobic and anaerobic, in relation to intensity, or acute (a single bout of exercise) and chronic (exercise training, repeated bouts of exercise), in relation to frequency. Both aerobic and anaerobic exercise can be performed in a chronic as well as an acute manner [9]. In the course of physical effort with the majority of aerobic processes, mitochondria contribute to ROS generation [4]. After physical effort characterised by increased participation of anaerobic processes in exercise metabolism, enhanced ROS generation occurs mainly as a result of ischemia/reperfusion [4][10]. What becomes the source of ROS under such conditions is the reaction catalysed by xanthine oxidase [10]. Acute exercise, both aerobic and anaerobic, leads to enhanced ROS generation [11]. Chronic physical activity, in turn, may protect against oxidative stress damage [12].

Oxidative damage to macromolecules in blood or in skeletal muscles induced by PA is observed mainly when the exercise is long-term and intensive [7]. Single intense anaerobic exercise (Wingate test) leads to an increase in lipid peroxide concentration in blood plasma in men [13]. An increase in the concentration of oxidative stress markers, i.e., conjugated dienes (CD) and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), was also demonstrated, for example, in untrained healthy men, 40 min after recovery from single submaximal physical exertion on an exercise bicycle [14], or in the blood of sportsmen after training [15][16]. It was also proven, however, that regular physical exercises conducted within a training session can increase the antioxidant abilities of the organism and thereby alleviate ROS levels [17][18]. The impact of training on the processes of oxidoreduction can be both positive and negative, and it depends on the training load, training specificity and the basal level of training [19]. Physical training can, for instance, lead to a compensatory increase in the activity of SOD and CAT in erythrocytes, which was demonstrated in kayakers and rowers after training in alpine conditions [20]. Gomes et al. [21], in turn, observed a reduction in oxidative stress in the skeletal muscles of rats with heart failure subjected to aerobic training of moderate intensity on a treadmill. The most recent research based on meta-analysis in elderly persons also confirms that regular aerobic exercise has a positive impact on the level of oxidative stress in blood (among others, the level of MDA and lipid peroxides decreased, and the level of SOD and total antioxidant potential (TAP) increased) [22]. It has been also demonstrated that physical exercise may have advantageous effects on brain function. The positive effects of physical exertion on the brain include, among other things, the activation of the internal antioxidant enzyme system [23]. Regular moderate aerobic exercise may promote antioxidant capacity in the brain. However, aerobic exhausted exercise, anaerobic high-intensity exercise, or various forms of combining these types of effort may lead to weakening of the antioxidant barrier in the brain [24].

Initially, it was thought that ROS and RNS have only toxic activity, and their enhanced generation results in damage to cellular components [25], including neurodegeneration [26]. More recent research, however, demonstrates that they can also act as critical signalling molecules, inducing advantageous adaptive changes in response to stress. It was shown that ROS released as mediators from systemic tissues/cells during physical training can also contribute to changes in the structure and function of the brain [27]. Regular performance of physical exercises may increase capillarization and neurogenesis via neurotrophic factors, decrease oxidative damage, and enhance repair of oxidative damage in the brain [26]. Physical exertion improves the function of the endothelium by increasing the blood flow, which leads to increased shear stress, stimulating the release of nitric oxide (•NO; a type of RNS) [28]. In the case of neurodegeneration, a disorder in the functioning of the blood–brain barrier, which is built of endothelial cells, is frequently observed [28][29]. The released •NO plays a significant role not only in the functioning of the circulatory system but also in that of the immune and nervous systems (as a neurotransmitter) [30].

2. The Influence of Physical Exercise on Redox Balance in Aging and Brain Diseases

The human population is aging and, consequently, age-related neurodegenerative disorders are becoming an increasingly serious public health problem. Additionally, lack of PA, overeating and sleep disturbances can promote neurodegeneration. These are agents that favor brain aging, as well as mental or neurological diseases [31][32]. As early as 65 years ago, Dr. Denham Harman showed ROS as a source of aging in his free radical theory of aging [33]. Nowadays the theory is still valid. It has only been extended to include free radical-induced mitochondrial DNA mutations [34]. The theory assumes gradual accumulation of oxidative damage to be a fundamental factor of cellular aging. Basically, senescence and degenerative diseases are attributed to the deleterious action of free radicals on cell constituents and connective tissues. In general, inside the cell, free radicals are generated in reactions catalyzed by oxidoreductive enzymes involving molecular oxygen, whereas in connective tissues by transient metals [33]. There are many studies that demonstrate ROS overproduction in the organism. Rodriguez-Manas et al. [35] postulated that age-dependent endothelial dysfunction is a complex process that involves several pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory mediators. They found that the main source of oxidative stress in nonpathological vascular aging is NADPH-dependent superoxide production. It was revealed that the activity of NADPH oxidase and the expression of NF-κB (the major transcription factor in the regulation of the response to oxidative stress) increase with age in humans [35]. Progressive redox imbalance decreases the functionality of neurons and increases the prevalence of ND. ROS, however, are also fundamental in redox signaling as second messengers. They are strictly related to Ca2+-mediated signaling and other critical intracellular pathways. Proper concentrations of OFRs are a basic condition for maintaining homeostasis [36]. As far as the free radical theory of aging is concerned, two main strategies seem to be most important in achieving that goal, namely the limitation of ROS production and strengthening of the antioxidant barrier [37]. Presently, many researchers believe that antioxidants counteract the harmful effects of aging and neurodegeneration [36]. Nevertheless, as already mentioned in Section 3, clinical trials have yielded disappointing and often confusing (mutually exclusive) findings, in contrast to the expected benefits of an antioxidant-based diet [38][39]. As regular physical training stimulates the antioxidant barrier and leads to adaptation to excessive concentrations of OFRs, stimulation of natural antioxidant mechanisms seems to be fully justified and necessary [40][41].

There is growing evidence of the positive effects of PA on aging and brain diseases [42]. It is emphasized that lifestyle factors, including PA, play a great role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. A meta-analysis showed that there is an inverse relationship between regular PA and the risk of developing AD [37]. There are also findings that indicate that aerobic fitness (endurance performance) is negatively correlated with loss of nervous tissue and cognitive deterioration with age [43]. Physical exercises induce adaptive ROS-dependent responses in the nervous system, such as proliferation and differentiation of neuronal stem cells [40]. Cognition improvement related to regular PA may be associated with an intensification of angiogenesis, synaptogenesis, synthesis of neurotransmitters and an increase in antioxidant capacity [37]. Bernardo et al. [44] observed positive alterations in mitochondrial oxygen consumption in both synaptosomal and non-synaptosomal brain mitochondria in AD-like rat models, where the rats were performing regular and long-term physical training (endurance running on a wheel). They observed neurobehavioral improvements in the rats. The authors suggested that endurance training increased mitochondrial biogenesis in the hippocampus through the activation of specific genes. PA can possibly prevent and reverse phenotypic impairments associated with AD. Interestingly, they also found that voluntarily performed PA (irregular and non-standardized) was not able to counteract AD-related deleterious consequences [44]. Mitochondria play a pivotal role in the mechanisms involved in cell death. They have a crucial role in the redox balance, regulate apoptotic pathways and contribute to the regulation of synaptic plasticity (a role in neurotransmission). They are also involved in the regulation of intracellular calcium concentration. Impairment of mitochondrial function results in cellular alterations ranging from subtle changes to cell death and tissue degeneration. Supra-physiological production of mitochondrial ROS due to a defective scavenging system is associated with aging and age-related diseases of the brain, as mentioned in Section 3 [45].

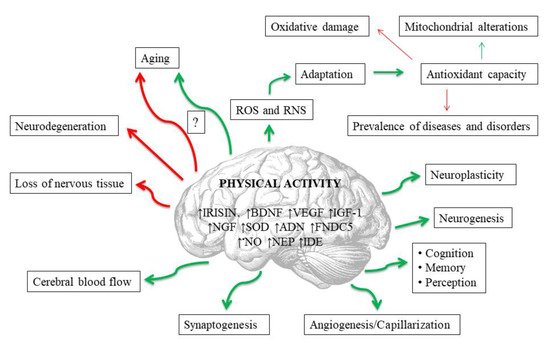

Exerkines are potentially the most important mediators of the neuroprotective effects of exercise [46] (Figure 1). These are the substances produced and secreted by various tissues into the peripheral blood during physical exertion, and which affect the entire organism [47]. For example, physical activity triggers the upregulation of exerkines in various tissues that directly or indirectly alleviate neurodegeneration processes in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [46]. Among these substances an important role is played, i.a., by compounds that affect the redox balance. The probable exercise-induced neuroprotection may result from upregulated antioxidant defense (particularly SOD) and may be related to beneficial mitochondrial adaptations, as well as to an increase in concentrations of other exerkines, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), nerve growth factor (NGF) and VEGF, which are also dependent on redox signaling. Other exerkines that affect oxidant–antioxidant equilibrium include: irisin, adiponectin (ADN), fibronectin type III domain containing 5 (FNDC5), neprilysin (NEP) and insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) [46]. Irisin is the best studied of the aforementioned. This is a skeletal muscle-secreted myokine, produced in response to physical exercise, which has protective functions in both the central and the peripheral nervous systems, including the regulation of BDNF [48]. Irisin enters CNS through the blood–brain barrier, and enhances BDNF synthesis and release, leading to augmented neuroplasticity achieved by the collaboration of irisin and BDNF [48][49]. Moreover, the protein is expressed not only in skeletal muscles but also in the brain [50]. It has been proven, for example, that it largely inhibits brain infarct volume and reduces neuroinflammation and post-ischemic oxidative stress [48][49]. In general, the dynamic changes in exerkine levels could be used as laboratory biomarkers for monitoring the effectiveness and appropriateness of the clinically prescribed exercise interventions, thus enabling the development of customized exercise therapy for individuals of varied ages, genders, and health states [46].

Figure 1. Potential impacts of regular physical activity on brain in human. Red lines mean negative impact, and green ones positive. Abbreviations are listed at the end of the article.

Neuronal benefits resulting from PA are also mediated by •NO, another neurotransmitter. The increase in •NO results in an improvement of the cerebral blood flow, which is associated with increased activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Upregulated antioxidant defense in CNS, as a result of regular physical exercise, leads to a decrease in the concentration of oxidative damage markers that are neurotoxic per se, e.g., 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG; a marker of DNA oxidative damage) [45] (Figure 1). The neuroprotective impact of physical training can also be assumed in PD patients in relation to aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). The metabolism of dopamine results in the formation of toxic 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) and H2O2, which are found in elevated concentrations in PD patients due to decreased vesicular uptake of cytosolic dopamine and decreased DOPAL detoxification by ALDH. Hence, it was reported that regular physical exercise increased the gene expression of ALDH in the brains of senescent female mice [40]. Moreover, Sellami et al. [51] stated that regular PA plays an important role in telomere maintenance and DNA methylation, possibly through its ability to alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation.

As already mentioned, neurodegeneration affects elderly people and PA can also alter antioxidant status in these individuals. Rousseau et al. [41] revealed increased activity of GPX in subjects aged 68.1 ± 3.1 years who were performing a minimum of three training sessions per week, with a session duration of less than 1 h each. PA of moderate intensity proved to be sufficient to improve antioxidant defense. Studied SOD and GR activities did not change in a statistically significant way [41]. Interestingly, Pérez et al. [52] reported that overexpression of antioxidant enzymes in mice did not extend their life span. Melo et al. [53], in turn, found that regular exercise bouts implemented at the early stage of neurodegeneration alleviate oxidative stress (measured by H2O2 levels and SOD activity) and improve neuronal functionality in the motor cortex in rats, which resulted from restored proteostasis. Almeida et al. [54] put forward a similar conclusion. The findings of their study confirm that PA prevents H2O2 production in rats during early neurodegeneration. However, the mechanism still remains unclear.

To date, despite a large number of studies on the effects of PA on the oxidant–antioxidant system, fully consistent conclusions have not been drawn. It is evident that physical exercise can also negatively affect the human organism, including the aging process, especially in aging individuals [55], because of lower antioxidant capacity, as mentioned [56][55]. Basically, high-intensity and prolonged exercise leads to redox imbalance, which has been shown to cause disorders in skeletal muscles and peripheral fatigue [55] (Figure 1). The evaluation of optimal PA intensity seems to be especially important, as it should be appropriate for the individuals who are the focus of the research.

3. Conclusions

It has long been known that PA together with healthy diet are key lifestyle factors that promote health, including brain health [57]. PA delays aging and improves cognition and memory [58][59]. However, exercise bouts may generate large amounts of ROS and RNS, and free radicals are considered to be the main source of molecular damage to cellular constituents resulting in aging [7]. There is no certainty as to whether free radicals are or may be also ethological agents. Nevertheless, most diseases and many disorders are associated with oxidative stress, the most common disturbance of the oxidant–antioxidant balance [60]. The antioxidant defense is inversely dependent on aging—the more advanced age, the weaker the defense. ND, in contrast, are directly dependent on age [56]. Interestingly, PA as a potential source of oxidative stress can lead to beneficial adaptation mechanisms, which are based on increased antioxidant capacity [61][62]. In general, physical exertion also positively affects the redox balance in elderly persons [41]. It was found that ROS released from systemic tissues during PA can contribute as mediators to changes in the structure and function of the brain [27]. Regular performance of physical exercises may, via neurotrophic factors, increase capillarization and neurogenesis, as well as decrease oxidative stress and enhance repair of oxidative damage in the brain [26]. Moreover, regular exercise bouts improve blood supply to the brain (increased •NO concentration) [28] (Figure 1). Lastly, the musculoskeletal system is positively correlated with brain size [58], and endurance performance is negatively correlated with loss of brain tissue and cognitive deterioration with age in humans [43]. This can result from the need of our remote ancestors to move in order to acquire food. This assumption is supported by research in rodents and other animals [58]. All of the aforementioned findings suggest that regular physical training can be a powerful tool for the maintenance of proper brain function throughout the lifespan. This also applies to brain disorders, principally to their prevention or delaying/alleviating their symptoms. Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to implement regular PA in the case of patients suffering from mental or neurodegenerative diseases, due to their restricted mobility in general. For this reason, there are very few direct studies on the impact of PA on these individuals. Effects of PA on the oxidant–antioxidant system in humans have been mainly studied in young and middle-aged adults. Therefore, conclusions on this issue are not fully applicable in the context of patients with neurodegenerative diseases. Apart from that, physical exercise can negatively affect the human organism as far as aging processes are concerned [55]. Thus, the evaluation of optimal PA intensity and appropriate selection of exercise type seem to be of special importance, and should be set individually.

The issue of whether antioxidant supplementation should be advised remains in question. According to current knowledge, it may seem justified and necessary [63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70]. However, there is a problem with the permeability of antioxidants through the blood–brain barrier. It is insufficient to obtain a significant antioxidant effect on neurons. In addition, most studies have been performed in vitro, and clinical trials have shown inconsistent outcomes [38][39]. Nonetheless, promising results have been provided by research on the chemical modification of natural compounds known for their high antioxidant abilities [71]. Moreover, there is debate as to whether consuming large amounts of antioxidants in supplement form actually benefits health [72]. Antioxidants themselves may act as pro-oxidants in some cases and aggravate pathological processes [73]. In 2013, renowned Nobel laureate James Watson warned that antioxidants in late-stage cancers can promote cancer progression [74]. Moreover, antioxidant supplementation may suppress the synthesis and formation of endogenous antioxidants and other cell adaptation mechanisms, such as better energetic metabolism [75]. Mentor and Fisher [76] demonstrated that an excessive intake of antioxidants disturbs blood–brain barrier functionality and angiogenic properties, as well as impairs the repair function of brain capillaries, compromising the patient’s recovery. Many plants and fruits contain potent natural antioxidant compounds that can protect cells against oxidative stress [65]. At the same time, PA has been proven to be effective in enhancing the oxidant–antioxidant balance [61]. Therefore, it seems that the best solution is to use a diet rich in natural antioxidants along with regular, albeit moderate, PA.

References

- Alkhatib, A.; Feng, W.H.; Huang, Y.J.; Kuo, C.H.; Hou, C.W. Anserine reverses exercise-induced oxidative stress and preserves cellular homeostasis in healthy men. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1146.

- Tsao, J.P.; Liu, C.C.; Wang, H.F.; Bernard, J.R.; Huang, C.C.; Cheng, I.S. Oral resveratrol supplementation attenuates exercise-induced interleukin-6 but not oxidative stress after a high cycling challenge in adults. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 2137–2145.

- Powers, S.K.; Jackson, M.J. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1243–1276.

- Woźniak, A. Signs of oxidative stress after exercise. Biol. Sport 2003, 20, 93–112.

- Kavazis, A.N.; Talbert, E.E.; Smuder, A.J.; Hudson, M.B.; Nelson, W.B.; Powers, S.K. Mechanical ventilation induces diaphragmatic mitochondrial dysfunction and increased oxidant production. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 842–850.

- Dominiak, K.; Jarmuszkiewicz, W. The Relationship between mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production and mitochondrial energetics in rat tissues with different contents of reduced coenzyme Q. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 533.

- Powers, S.K.; Nelson, W.B.; Hudson, M.B. Exercise-induced oxidative stress in humans: Cause and consequences. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 942–950.

- Vollaard, N.B.; Shearman, J.P.; Cooper, C.E. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Myths, realities and physiological relevance. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 1045–1062.

- Gomes, E.C.; Silva, A.N.; de Oliveira, M.R. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the beneficial roles of exercise-induced production of reactive species. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 756132.

- Souza-Junior, T.; Lorenço-Lima, L.; Ganini, D.; Vardaris, C.; Polotow, T.; Barros, M. Delayed uric acid accumulation in plasma provides additional anti-oxidant protection against iron-triggered oxidative stress after a wingate test. Biol. Sport. 2014, 31, 271–276.

- Bloomer, R.J.; Goldfarb, A.H.; Wideman, L.; McKenzie, M.J.; Consitt, L.A. Effects of acute aerobic and anaerobic exercise on blood markers of oxidative stress. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 276–285.

- Bouzid, M.M.; Filaire, E.; McCall, A.; Fabre, C. Radical oxygen species, exercise and aging: An update. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1245–1261.

- Taito, S.; Sekikawa, K.; Oura, K.; Kamikawa, N.; Matsuki, R.; Kimura, T.; Takahashi, M.; Inamizu, T.; Hamada, H. Plasma oxidative stress is induced by single-sprint anaerobic exercise in young cigarette smokers. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2013, 33, 241–244.

- Sutkowy, P.; Woźniak, A.; Boraczyński, T.; Mila-Kierzenkowska, C.; Boraczyński, M. Postexercise impact of ice-cold water bath on the oxidant-antioxidant balance in healthy men. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 706141.

- Woźniak, A.; Mila-Kierzenkowska, C.; Szpinda, M.; Chwalbinska-Moneta, J.; Augustyńska, B.; Jurecka, A. Whole-body cryostimulation and oxidative stress in rowers: The preliminary results. Arch. Med. Sci. 2013, 9, 303–308.

- Rakowski, A.; Jurecka, A.; Rajewski, R. Whole-body cryostimulation in kayaker women: A study of the effect of cryogenic temperatures on oxidative stress after the exercise. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2009, 49, 201–207.

- De Sousa, C.V.; Sales, M.M.; Rosa, T.S.; Lewis, J.E.; De Andrade, R.V.; Simões, H.G. The antioxidant effect of exercise: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 277–293.

- Cho, S.Y.; So, W.Y.; Roh, H.T. Effect of C242T polymorphism in the gene encoding the NAD(P)H oxidase p22(phox) subunit and aerobic fitness levels on redox state biomarkers and DNA damage responses to exhaustive exercise: A randomized trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4215.

- Finaud, J.; Lac, G.; Filaire, E. Oxidative stress: Relationship with exercise and training. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 327–358.

- Woźniak, A.; Drewa, G.; Chęsy, G.; Rakowski, A.; Rozwodowska, M.; Olszewska, D. Effect of altitude training on the peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in sportsmen. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1109–1113.

- Gomes, M.J.; Pagan, L.U.; Lima, A.R.R.; Reyes, D.R.A.; Martinez, P.F.; Damatto, F.C.; Pontes, T.H.D.; Rodrigues, E.A.; Souza, L.M.; Tosta, I.F.; et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on cardiac remodelling and skeletal muscle oxidative stress of infarcted rats. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 5352–5362.

- Ye, Y.; Lin, H.; Wan, M.; Qiu, P.; Xia, R.; He, J.; Tao, J.; Chen, L.; Zheng, G. The effects of aerobic exercise on oxidative stress in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2021, 12, 701151.

- Lee, S.J. Effects of preconditioning exercise on nitric oxide and antioxidants in hippocampus of epileptic seizure. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2019, 15, 757–762.

- Camiletti-Moirón, D.; Aparicio, V.A.; Aranda, P.; Radak, Z. Does exercise reduce brain oxidative stress? A systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, e202–e212.

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84.

- Radak, Z.; Ihasz, F.; Koltai, E.; Goto, S.; Taylor, A.W.; Boldogh, I. The redox-associated adaptive response of brain to physical exercise. Free Radic. Res. 2014, 48, 84–92.

- Lucas, S.J.; Cotter, J.D.; Brassard, P.; Bailey, D.M. High-intensity interval exercise and cerebrovascular health: Curiosity, cause, and consequence. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015, 35, 902–911.

- Małkiewicz, M.A.; Szarmach, A.; Sabisz, A.; Cubała, W.J.; Szurowska, E.; Winklewski, P.J. Blood-brain barrier permeability and physical exercise. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 15.

- Zlokovic, B.V. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 2008, 57, 178–201.

- Sutkowy, P.; Woźniak, A.; Mila-Kierzenkowska, C. Positive effect of generation of reactive oxygen species on the human organism. Med. Biol. Sci. 2013, 27, 13–17.

- Petrovic, S.; Arsic, A.; Ristic-Medic, D.; Cvetkovic, Z.; Vucic, V. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant supplementation in neurodegenerative diseases: A review of human studies. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1128.

- Real, C.C.; Binda, K.H.; Landau, A.M. Treadmill exercise and neuroinflammation: Links with aging. In Factors Affecting Neurological Aging; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 385–401.

- Harman, D. Aging: A theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Gerontol. 1956, 11, 298–300.

- Ziada, A.S.; Smith, M.S.R.; Côté, H.C.F. Updating the free radical theory of aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 575645.

- Rodríguez-Mañas, L.; El-Assar, M.; Vallejo, S.; López-Dóriga, P.; Solís, J.; Petidier, R.; Montes, M.; Nevado, J.; Castro, M.; Gómez-Guerrero, C.; et al. Endothelial dysfunction in aged humans is related with oxidative stress and vascular inflammation. Aging Cell. 2009, 8, 226–238.

- Muñoz, P.; Ardiles, Á.O.; Pérez-Espinosa, B.; Núñez-Espinosa, C.; Paula-Lima, A.; González-Billault, C.; Espinosa-Parrilla, Y. Redox modifications in synaptic components as biomarkers of cognitive status, in brain aging and disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 189, 111250.

- Paillard, T. Preventive effects of regular physical exercise against cognitive decline and the risk of dementia with age advancement. Sports Med. Open 2015, 1, 20.

- Angelova, P.R.; Abramov, A.Y. Role of mitochondrial ROS in the brain: From physiology to neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 692–702.

- Ruiz-Perera, L.M.; Höving, A.L.; Schmidt, K.E.; Cenan, S.; Wohllebe, M.; Greiner, J.F.W.; Kaltschmidt, C.; Simon, M.; Knabbe, C.; Kaltschmidt, B. Neuroprotection mediated by human blood plasma in mouse hippocampal slice cultures and in oxidatively stressed human neurons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9567.

- Quan, H.; Koltai, E.; Suzuki, K.; Aguiar, A.S.; Pinho, R.; Boldogh, I.; Berkes, I.; Radak, Z. Exercise, redox system and neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165778.

- Rousseau, A.S.; Margaritis, I.; Arnaud, J.; Faure, H.; Roussel, A.M. Physical activity alters antioxidant status in exercising elderly subjects. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 463–470.

- Vanzella, C.; Neves, J.D.; Vizuete, A.F.; Aristimunha, D.; Kolling, J.; Longoni, A.; Gonçalves, C.A.S.; Wyse, A.T.S.; Netto, C.A. Treadmill running prevents age-related memory deficit and alters neurotrophic factors and oxidative damage in the hippocampus of Wistar rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 334, 78–85.

- Burtscher, J.; Millet, G.P.; Place, N.; Kayser, B.; Zanou, N. The muscle-brain axis and neurodegenerative diseases: The key role of mitochondria in exercise-induced neuroprotection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6479.

- Bernardo, T.C.; Beleza, J.; Rizo-Roca, D.; Santos-Alves, E.; Leal, C.; Martins, M.J.; Ascensão, A.; Magalhães, J. Physical exercise mitigates behavioral impairments in a rat model of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 379, 112358.

- Bernardo, T.C.; Marques-Aleixo, I.; Beleza, J.; Oliveira, P.J.; Ascensão, A.; Magalhães, J. Physical exercise and brain mitochondrial fitness: The possible role against Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2016, 26, 648–663.

- Liang, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.D.; Luo, X.; Wu, L.L.; Chen, Z.W.; Wei, G.H.; Zhang, K.Q.; Du, Z.-A.; Li, R.-Z.; So, K.-F.; et al. All roads lead to Rome—a review of the potential mechanisms by which exerkines exhibit neuroprotective effects in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res. 2022, 17, 1210–1227.

- Yu, M.; Tsai, S.-F.; Kuo, Y.-M. The therapeutic potential of anti-inflammatory exerkines in the treatment of atherosclerosis. IJMS. 2017, 18, 1260.

- Jin, Y.; Sumsuzzman, D.M.; Choi, J.; Kang, H.; Lee, S.-R.; Hong, Y. Molecular and functional interaction of the myokine irisin with physical exercise and Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules 2018, 23, 3229.

- Pesce, M.; La Fratta, I.; Paolucci, T.; Grilli, A.; Patruno, A.; Agostini, F.; Bernetti, A.; Mangone, M.; Paolini, M.; Invernizzi, M.; et al. From exercise to cognitive performance: Role of irisin. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7120.

- Dun, S.L.; Lyu, R.-M.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chang, J.-K.; Luo, J.J.; Dun, N.J. Irisin-immunoreactivity in neural and non-neural cells of the rodent. Neuroscience 2013, 240, 155–162.

- Sellami, M.; Bragazzi, N.; Prince, M.S.; Denham, J.; Elrayess, M. Regular, intense exercise training as a healthy aging lifestyle strategy: Preventing DNA damage, telomere shortening and adverse DNA methylation changes over a lifetime. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 652497.

- Pérez, V.I.; van Remmen, H.; Bokov, A.; Epstein, C.J.; Vijg, J.; Richardson, A. The overexpression of major antioxidant enzymes does not extend the lifespan of mice. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 73–75.

- Melo, K.P.; Silva, C.M.; Almeida, M.F.; Chaves, R.S.; Marcourakis, T.; Cardoso, S.M.; Demasi, M.; Netto, L.E.S.; Ferrari, M.F.R. Mild exercise differently affects proteostasis and oxidative stress on motor areas during neurodegeneration: A comparative study of three treadmill running protocols. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35, 410–420.

- Almeida, M.F.; Silva, C.M.; Chaves, R.S.; Lima, N.C.R.; Almeida, R.S.; Melo, K.P.; Demasi, M.; Fernandes, T.; Oliveira, E.M.; Netto, L.E.S.; et al. Effects of mild running on substantia nigra during early neurodegeneration. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1363–1370.

- Sessa, F.; Messina, G.; Russo, R.; Salerno, M.; Castruccio Castracani, C.; Distefano, A.; Li Volti, G.; Calogero, A.E.; Cannarella, L.; Mongioi’, L.M.; et al. Consequences on aging process and human wellness of generation of nitrogen and oxygen species during strenuous exercise. Aging Male 2020, 23, 14–22.

- Díaz, M.; Mesa-Herrera, F.; Marín, R. DHA and its elaborated modulation of antioxidant defenses of the brain: Implications in aging and AD neurodegeneration. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 907.

- Panegyres, K.P.; Panegyres, P.K. The ancient Greek discovery of the nervous system: Alcmaeon, Praxagoras and Herophilus. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 29, 21–24.

- Di Liegro, C.M.; Schiera, G.; Proia, P.; Di Liegro, I. Physical activity and brain health. Genes 2019, 10, 720.

- Erickson, K.I.; Hillman, C.; Stillman, C.M.; Ballard, R.M.; Bloodgood, G.; Conroy, D.E.; Macko, R.; Marquez, D.X.; Petruzzello, S.J.; Powel, K.E.; et al. Physical activity, cognition, and brain outcomes: A review of the 2018 physical activity guidelines. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1242–1251.

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, C.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aqqurwal, B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1603–1616.

- Peternelj, T.T.; Coombes, J.S. Antioxidant supplementation during exercise training: Beneficial or detrimental? Sports Med. 2011, 41, 1043–1069.

- Sutkowy, P.; Woźniak, A.; Boraczyński, T.; Boraczyński, M.; Mila-Kierzenkowska, C. The oxidant-antioxidant equilibrium, activities of selected lysosomal enzymes and activity of acute phase protein in peripheral blood of 18-year-old football players after aerobic cycle ergometer test combined with ice-water immersion or recovery at room temperature. Cryobiology 2017, 74, 126–131.

- Moosmann, B.; Behl, C. Antioxidants as treatment for neurodegenerative disorders. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2002, 11, 1407–1435.

- Albarracin, S.L.; Stab, B.; Casas, Z.; Sutachan, J.J.; Samudio, I.; Gonzalez, J.; Gonzalo, L.; Capani, F.; Morales, L.; Barreto, G.E. Effects of natural antioxidants in neurodegenerative disease. Nutr. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1–9.

- Vauzour, D. Dietary polyphenols as modulators of brain functions: Biological actions and molecular mechanisms underpinning their beneficial effects. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 914273.

- Feng, Y.; Wang, X. Antioxidant therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 472932.

- Conti, V.; Izzo, V.; Corbi, G.; Russomanno, G.; Manzo, V.; De Lise, F.; Di Donato, A.; Filipelli, A. Antioxidant supplementation in the treatment of aging-associated diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 24.

- Velusamy, T.; Panneerselvam, A.S.; Purushottam, M.; Anusuyadevi, M.; Pal, P.K.; Jain, S.; Essa, M.M.; Guillemin, G.J.; Kandasamy, M. Protective effect of antioxidants on neuronal dysfunction and plasticity in Huntington’s disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 3279061.

- González-Fuentes, J.; Selva, J.; Moya, C.; Castro-Vázquez, L.; Lozano, M.V.; Marcos, P.; Plaza-Oliver, M.; Rodríguez-Robledo, V.; Santander-Ortega, M.; Villaseca-González, N.; et al. Neuroprotective natural molecules, from food to brain. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 721.

- Lee, K.H.; Cha, M.; Lee, B.H. Neuroprotective effect of antioxidants in the brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7152.

- Fernandes, C.; Pinto, M.; Martins, C.; Gomes, M.J.; Sarmento, B.; Oliveira, P.J.; Remião, F.; Borges, F. Development of a PEGylated-based platform for efficient delivery of dietary antioxidants across the blood-brain barrier. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 1677–1689.

- Bast, A.; Haenen, G.R.M.M. Ten misconceptions about antioxidants. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 430–436.

- Sarangarajan, R.; Meera, S.; Rukkumani, R.; Sankar, P.; Anuradha, G. Antioxidants: Friend or foe? Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 1111–1116.

- Watson, J. Oxidants, antioxidants and the current incurability of metastatic cancers. Open Biol. 2013, 3, 120144.

- Salehi, B.; Martorell, M.; Arbiser, J.L.; Sureda, A.; Martins, N.; Maurya, P.K.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kumar, P.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Antioxidants: Positive or negative actors? Biomolecules 2018, 8, 124.

- Mentor, S.; Fisher, D. Aggressive antioxidant reductive stress impairs brain endothelial cell angiogenesis and blood brain barrier function. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2017, 14, 71–81.

More

Information

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

660

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

12 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No