| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andrea del Carmen Carrillo Andrade | + 1300 word(s) | 1300 | 2022-01-06 09:14:46 | | | |

| 2 | Yvaine Wei | Meta information modification | 1300 | 2022-01-11 03:23:21 | | |

Video Upload Options

Social media has become a fundamental platform where users interact and promote public values. Memetics facilitates this phenomenon. Memes have three main characteristics: (1) Diffuse at the micro-level but shape the macrostructure of society; (2) Are based on popular culture; (3) Travel through competition and selection. The findings suggest that, during a public discussion, it is common to use humor based on popular culture to question authority. Furthermore, a message becomes a meme when it evidences the gap between reality and expectations (normativity).

1. Introduction

In the era of Web 2.0 and the hipermediations (Scolari 2008), presidential debates are commented by everybody and anybody, without intermediates or filters in diverse platforms simultaneously. The preferred platform is the microblogging site Twitter: It resembles more traditional news media; besides, it is conceived to distribute and share news (Boehmer and Tandoc 2015). For instance, “the 2012 U.S. presidential election has been described as the “Twitter election” (McKinney et al. 2013, p. 556) based on the fact that “Twitter political activity increased dramatically over the course of the campaign” (Houston et al. 2013, p. 549). “Social media are platforms which can bring about the further personalization of politics (…) in how we discuss and document our experience of political issues” (Highfield 2016). One way in which this personalization occurs is through memes. Political memes are units of content that travel through competition and selection and diffuse at the micro-level but shape the macrostructure of society; also, they use and have become cultural items that people can potentially imitate.

2. Results

2.1. The First American Debate

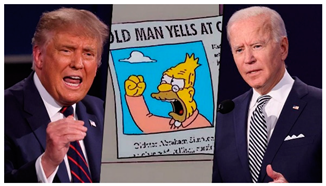

Table 1 shows two of the most popular memes and interactions developed towards the candidate debate.

| Meme 1 | Meme 2 |

|---|---|

|

|

| Classification: Public discussion memes Cultural items: Cartoon of grandpa Simpson, under the title “Old man yells at cloud”, surrounded by the pictures of Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Critical. Scope: First result under the search engine “debate Trump Biden meme”. In this case, 109 interactions from the original meme. |

Classification: Public discussion memes Cultural items: Actor Mark Hamill, who interprets Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars saga; The Star Wars Holiday Special (a spin-off). Critical. Scope: 1,000,000 likes and 97,000 comments. |

2.2. The Ecuadorian Debate

In general terms, citizens criticized the form of the debate and the interventions as any candidate went deep enough to clarify how they would deliver on their promises (Table 2). Interestingly, both candidates used data and sources to reply to the questions. Nevertheless, it can be dangerous because the evidence presented was tendentious, contributing to disinformation (Cervi and Carrillo-Andrade 2019), a critical aspect of Ecuador’s political system.

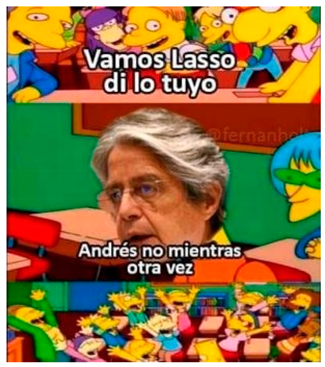

| Meme 3 | Meme 4 |

|---|---|

|

|

| Copy: “Come on, Lasso, say the line”; “Andrés, don’t lie again”. Classification: Public discussion memes Cultural items: Frame series of a famous chapter of The Simpsons with Lasso’s catchy phrase against Arauz. Scope: First result under the search engine “debate Lasso Arauz meme”; part of Meme Generator |

Copy: If I were the moderator #PresidentialDebateEC. “Quit talking and hit him” Classification: Public discussion memes Cultural items: Frame of the famous series “Malcolm in the Middle” with Dewey (the youngest brother” saying, “Quit talking and hit him”. Scope: More than 1000 likes, 412 retweets, and 11 comments. |

3. Findings

Memes mutate and adapt constantly, not just in their content but also in their form. The use of text placed on the interface of Twitter is becoming a more popular form of meme; it is read as an image, and even it looks similar to plain text, it gives crucial information as the source. In this sense, some messages become famous by their creator rather than by their words. Nevertheless, these tend to have a short life because common prosumers cannot reproduce them and acquired the same impact: They may be sticky but not easily spreadable (Jenkins et al. 2013). The life of these memes is even shorter if they belong to the public discussion memes category.

Ecuador and the United States share cultural items and humor; this becomes evident when analyzing public discussion memes. Both countries use Simpsons’ frames to generate humor and to criticize reality. This evidences how reappropriation occurs as an American T.V. show can be a common tongue for Latin America. In contrast, the debate of the United States originated new memes and a template for them; that is the case of “That Debate Was The Worst Thing I’ve Ever Seen”. Ecuadorian popular memes were merely an adaptation of old ones that have already been circulating on the Internet. Then, it is crucial to hold in mind that “humorous texts relate to the symbols and stereotypes specific to the place and time of their creation, reflecting norms and aspirations, power structures, and collective fears” (Shifman et al. 2014, p. 727). So, that a developing country shares the cultural items of a member of the G7 shows an inner relationship of power.

Moreover, normativity in social media comes from sharing public values. What occurs with memes is that they give the impression that while all citizens share these public values, politicians do not: Humor and critics originate. Then, memes reflect rivalry between citizens and politicians and normalize problematic perspectives. Nevertheless, what occurs is that messages—because they need to impact—tend to ambiguity and trivialization of issues or even to the manipulation by political elites (Phillips and Milner 2017). What is more, in Ecuadorian politics, populism has reinforced the perception of politicians as “the others”; then, memes tend to spread more when they call to citizen identification against the ones that govern.

References

- Scolari, Carlos. 2008. Hipermediaciones: Elementos Para Una Teoría de la Comunicación Digital Interactiva. Barcelona: Gedisa Editorial.

- Boehmer, Jan, and Edson C. Tandoc. 2015. Why We Retweet: Factors Influencing Intentions to Share Sport News on Twitter. International Journal of Sport Communication 8: 212–32.

- McKinney, Mitchell S., J. Brian Houston, and Joshua Hawthorne. 2013. Social Watching a 2012 Republican Presidential Primary Debate. American Behavioral Scientist 58: 556–73.

- Houston, J. Brian, Mitchell Mckinney, Joshua Hawthorne, and Matthew Spialek. 2013. Frequency of Tweeting During Presidential Debates: Effect on Debate Attitudes and Knowledge. Communication Studies 64: 548–60.

- Highfield, Tim. 2016. Social Media and Everyday Politis. Ebook. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Troi, Ernesto, and Alvarado Chávez. 2018. Los Memes Como Manifestación Satírica de la Opinión Pública en la Política Ecuatoriana: Estudio del Caso ‘Rayo Correizador’. Master’s thesis, Universidad Casa Grande, Guayaquil, Ecuador; pp. 1–135.

- Shifman, Limor. 2013a. Memes in a Digital Culture. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Phillips, Whitney, and Ryan Milner. 2017. The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Cambridge: Polity Pr.

- Ryan, Charlotte, and William A. Gamson. 2006. The Art of Reframing Political Debates. Contexts 5: 13–18.

- Dailymail. 2020. Internet Explodes with Memes as Despairing Viewers Watch Farcical Contest between Trump and Biden. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8788455/Internet-explodes-memes-Trump-Biden-debate.html (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Parker, Marla A., and Barry Bozeman. 2018. Social Media as a Public Values Sphere. Public Integrity 20: 386–400.

- Cervi, Laura, and Andrea Carrillo-Andrade. 2019. Post-Truth and Disinformation: Using Discourse Analysis to Understand the Creation of Emotional and Rival Narratives Post-Verdad y Desinformación. Uso del Análisis del Discurso Para Comprender la Creación de Narrativas Emocionales y Rivales en Brexit Pó 10: 125–50.

- La Verdad. 2021. Lo Mejor del Debate: Los Memes. Aquí te Mostramos Algunos. Available online: https://www.laverdad.ec/entretenimiento/2021/3/22/lo-mejor-del-debate-los-memes-aqui-te-mostramos-algunos-5591.html (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media. New York: New York University Press.

- Shifman, Limor, Hadar Levy, and Mike Thelwall. 2014. Internet Jokes: The Secret Agents of Globalization? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19: 727–43.