Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leucio Rossi | + 4609 word(s) | 4609 | 2021-12-14 09:10:49 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 4609 | 2022-01-13 07:14:22 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 4609 | 2022-01-13 07:29:51 | | | | |

| 4 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 4609 | 2022-01-13 07:34:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Rossi, L. Green Diesel Production by Hydrodeoxygenation. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17976 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Rossi L. Green Diesel Production by Hydrodeoxygenation. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17976. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Rossi, Leucio. "Green Diesel Production by Hydrodeoxygenation" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17976 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Rossi, L. (2022, January 10). Green Diesel Production by Hydrodeoxygenation. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17976

Rossi, Leucio. "Green Diesel Production by Hydrodeoxygenation." Encyclopedia. Web. 10 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Non-renewable fossil fuels and the air pollution associated with their combustion have made it necessary to develop fuels that are environmentally friendly and produced from renewable sources. Vegetable oils are a renewable source widely used to produce biofuels due to their high energy density and similar chemical composition to petroleum derivatives, making them the perfect feedstock for biofuel production. Green diesel and other hydrocarbon biofuels, obtained by the catalytic deoxygenation of vegetable oils, represent a sustainable alternative to mineral diesel, as they have physico-chemical properties similar to derived oil fuels.

hydrodeoxygenation reaction

catalysis

green diesel

renewable raw materials

1. Green Diesel vs. Biodiesel

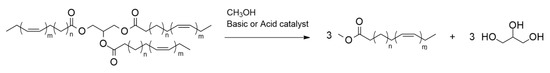

Biodiesel is the product obtained from the transesterification of edible and non-edible vegetable oils with methanol or ethanol in the presence of acid or basic catalysts [1]. The fatty acids contained in vegetable oil triglycerides are converted into the corresponding methyl esters (FAME) by the transesterification reaction (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Transesterification reaction for biodiesel production.

The main advantages of biodiesel relay to the use of renewable materials and to the reduction of polluting gas emissions. Moreover, the production process leads to high yields and requires mild operating conditions [2]. However, several drawbacks, such as high oxygen content, high corrosivity, storage instability, and limited miscibility with conventional fossil fuels, make biodiesel an unsuitable substitute for petrol diesel [3]. A valuable alternative to biodiesel is green diesel, which is obtained by the catalytic deoxygenation (DO) of vegetable oils. DO is a thermal process, typically conducted in a hydrogen atmosphere and with a heterogeneous metal catalyst, in which vegetable oils are converted into hydrocarbons. A DO commercial process was patented by Neste Oil [4]. This treatment produces a biofuel mainly consisting of n-alkanes, which is therefore chemically similar to mineral diesel, making it completely compatible and miscible in every proportion. The differences between biodiesel, green diesel, and petrol diesel can be seen in Table 1 [5].

Table 1. Physical properties of petrol diesel, biodiesel, and green diesel (Figure modified from [6]).

| Properties | Petrol Diesel | Biodiesel | Green Diesel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cetane Number 1 | 40 | 50–65 | 70–90 |

| Energy Density (MJ/kg) | 43 | 38 | 44 |

| Density (g/mL) | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.78 |

| Sulfur (ppm) | <10 | <1 | <1 |

| Cloud Point (°C) | −5 | −5, +15 | −20, +20 |

| Oxidative Stability | Good | Marginal | Good |

| Cold Flow Properties | Good | Poor | Poor |

1 Cetane number is an indicator of the combustion speed and compression needed for ignition of diesel fuel.

Both green diesel and biodiesel have a higher cetane number than conventional petrol diesel (higher for green diesel). Biodiesel is chemically different from petrol diesel. In fact, it has a high oxygen content and as a result a lower calorific value, energy density, and energy content [7]. In contrast, green diesel is chemically similar to petrol diesel and more suitable than biodiesel as its substitute. Both biodiesel and green diesel have low sulfur emissions [8], but unlike green diesel, biodiesel has higher nitrogen emissions. CO2 emissions are also significantly reduced. Han et al. [9] observed a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions of 41–63% in the case of jet biofuels produced by catalytic deoxygenation. Compared to green diesel, biodiesel has better properties as a lubricant, and it also has a higher flash point. In contrast, it has poorer oxidation stability, storage, and also poor cold flow properties [10]. On the other hand, green diesel has high oxidation stability, storage stability, and when properly treated by a hydroisomerization reaction (a reaction in which the n-alkanes of green diesel are partially converted into the corresponding branched isomers) it also has excellent cold properties [11]. Furthermore, the different chemical composition between biodiesel and petrol diesel implies that the former can only be used in a mixture with conventional diesel. In fact, it can be used pure only after the adaptation of the engine [10]. Green diesel, on the other hand, being chemically similar to petrol diesel, can completely replace conventional diesel.

2. Catalytic Deoxygenation (DO) Process

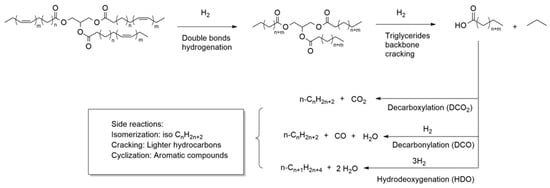

Catalytic deoxygenation (DO) is a thermic treatment, in a hydrogen atmosphere and with a heterogeneous catalyst, in which the triglycerides of vegetable oils are converted into hydrocarbon compounds. Gosselink and co-workers have written an exhaustive review on the reaction pathways that occur during DO over a model compound or real feedstock [12] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Possible reaction pathway during catalytic deoxygenation of vegetable oil (figure modified from [13]).

As suggested by Kubicka et al., the first step of DO involves the hydrogenation of the double bonds of unsaturated fatty acids [14]. Then, the triglycerides are broken down to obtain free fatty acids. The most common mechanism of triglyceride cleavage is a β-elimination reaction in which the triglyceride is converted into a free fatty acid and an unsaturated diglyceride. The diglyceride needs to be re-hydrogenated before undergoing further β-elimination to release a second fatty acid molecule. The third step of hydrogenation and β-elimination leads to the release of the third fatty acid and a propane molecule [15]. The free fatty acids can then follow three different reaction pathways according to the selectivity of the process: (a) a hydrodeoxygenation reaction (HDO), which forms an alkane with the same number of carbon atoms as the starting fatty acid and water; (b) decarbonylation (DCO); (c) decarboxylation (DCO2) reactions in which an alkane with a carbon atom less than the starting fatty acid is formed and the oxygen is released as CO and H2O (DCO) or CO2 (DCO2) [16]. Reaction selectivity can be driven by varying operating parameters, such as temperature and pressure, but also by varying the nature of the metal catalysts and the supporting material. The HDO route is preferable from the point of view of atom economy because it produces H2O as a by-product, though it consumes more hydrogen. In addition, water produced during the reaction could deactivate the catalyst [17]. The DCO2 route does not consume hydrogen but, on the other hand, it has a lower atom economy and produces CO2, which is a greenhouse gas. The catalytic deoxygenation produces a liquid product consisting of n-alkanes. Since it is chemically similar, green diesel is fully compatible with conventional diesel, and they can be mixed in any proportion. At this stage, however, the produced biofuel is not very suitable because it has poor cold properties [18]. Through the hydroisomerization process, a DO-similar process, the linear n-alkanes are converted into the corresponding branched isomers leading to a product with better cold properties [19]. The process is generally conducted at higher temperatures than DO; zeolite-supported metals (such as Pt/SAPO-11 where SAPO-11 are a medium-pore silicoaluminophosphate molecular sieve) are used as catalysts. Interestingly, after the isomerization reaction, the biofuel retains a similar cetane value [20]. Cracking and other secondary reactions favored by high temperatures are possible in DO. In these reactions, alkanes and fatty acids undergo a thermal cleavage yielding short-chain compounds. This reaction is an undesirable event if the intention is to produce a green diesel type of biofuel, while it is desirable for producing jet fuels or gasoline range biofuels [21]. Another possible side reaction is the aromatization reaction (cyclization of saturated alkanes followed by dehydrogenation). Normally, it is an undesirable reaction, as the aromatic compounds lower the calorific value of the fuel and lead to the deactivation of the catalysts. Nevertheless, in the case of jet fuels, a small percentage of aromatics is desirable [21]. Another possible reaction is the coking reaction in which alkanes, or aromatic compounds, can polymerize to form a carbonaceous residue consisting of heavy hydrocarbons. This reaction is highly undesirable because the presence of coke strongly deactivates the catalyst by adsorbing on it and blocking its pores. It is possible to reduce the effect of secondary reactions by changing the reaction parameters. The reactions mentioned so far take place in the liquid phase, but gas phase reactions are also possible (Figure 3).

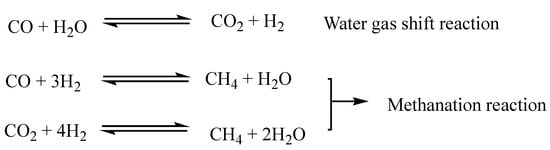

Figure 3. Gas phase reactions in catalytic deoxygenation of vegetable oils.

Considering the water–gas shift reaction, it is evident that driving the reaction towards H2 production would be profitable from the point of view of H2 consumption, but at the same time, it would be necessary to counteract methanation reactions that consume large quantities of hydrogen. DCO/DCO2 consume less H2 than HDO, but the formation of CO and CO2 in addition to strong methanation could lead DCO/DCO2 reactions to consume more H2 than HDO [22].

Catalytic deoxygenation can be affected by a large number of variables: the nature of the catalyst, temperature, reaction atmosphere, hydrogen pressure, solvent (whatever the reaction that was conducted in the presence of a solvent), the substrate, and also the reactor used. All these parameters influence conversion, reaction selectivity, hydrocarbon mixture distribution (gasoline range, jet fuel range, diesel range), isomerization, coke formation, and catalyst deactivation.

2.1. Catalyst and Support

As previously reported, DO reaction is a thermic, energy demanding treatment. The use of a catalyst reduces this demand. Here, we report the more promising catalysts for energy-saving and cost-effective processes, thanks to milder operating conditions. The choice of the active phase and support can greatly influence the distribution of products in the liquid phase and the conversion of the feedstock. The most commonly used catalysts are sulfided transition metal catalysts such as Mo and W doped with promoters such as Ni and Co (HDS catalysts). Kubicka et al., investigating the DO of rapeseed oil over sulfided NiMo/γ-Al2O3, Ni/γ-Al2O3 and Co/γ-Al2O3, observed that the bimetallic catalyst was more active than the monometallic ones. Moreover, Ni is more selective towards DCO/DCO2 and Mo towards HDO. The same amounts of the products deriving from both reactions were obtained using NiMo [23]. Comparative analysis of sulfided NiMo, NiW, CoMo, and CoW, supported on γ-Al2O3, SiO2, TiO2, SBA-15 (Santa Barbara amorphous-15 mesoporous silica), and HT (hydrotalcites layered double hydroxides), in rapeseed oil hydrotreatment, was performed by Horceck et al. [24]. They concluded that the most active catalyst was NiMo/γ-Al2O3. NiMo/γ-Al2O3 was also more active than NiCoMo and NiCoW trimetallic catalysts. They also studied the effect of the support, observing that the most active support was alumina together with SBA-15. If compared to SiO2, SBA-15 shows greater activity and different selectivity; with SBA-15, there is a greater prevalence of HDO, while SiO2 prefers DCO/DCO2. This is due to the high surface area of SBA-15 (650 m2/g) compared to SiO2 (57 m2/g) that improves the diffusion of the reagents inhibiting the breaking of the C–C bonds (and thus the DCO/DCO2) [24]. These catalysts are very active but also have the significant disadvantage of rapid deactivation via sulfur leaching. A catalyst’s deactivation by leaching can be minimized by using a sulfiding agent that reduces the leaching of the catalyst [25]. Senol et al. have also analyzed the effect of two sulfiding agents, H2S and CS2, observing that H2S was more effective than CS2. They actively participate in promoting DO by increasing the acidity of the catalyst and preventing catalyst deactivation. However, this leads to the formation of pollutant gases and contamination of the biofuel with sulfur [26]. Because of these limitations, the scientific community has focused on the development of non-sulfided catalysts. Generally, these catalysts are based on noble metals because are they are generally more active, although more expensive, than the corresponding reduced-transition metals [16][27]. Snare et al. compared the activity of several noble metals (Pd, Pt, Ir, Ru, Os) and Ni supported on AC (activated carbon), γ-Al2O3, Cr2O3, and SiO2 in the DO of oleic acid. It was evident that the most active catalysts were based on Pd and Pt, followed by Ni [16]. Morgan et al., investigating the hydrotreatment of tristearin, triolein, and soybean oil over 20 wt% Ni/C, 5 wt% Pd/C, and 1 wt% Pt/C under nitrogen atmosphere, observed that a sufficiently high content of supported metal can lead a Ni-based metal catalyst to be more active than a noble metal catalyst [28]. Additionally, Veriansyah et al., comparing the activity of monometallic Pd, Pt, and Ni-based catalysts with bimetallic catalysts such as reduced NiMo in the DO of soybean oil, observed that NiMo is also more active than noble catalysts [13]. Metal transition-based catalysts can also be a good alternative to typical sulfided catalysts. In fact, by comparing the activity of reduced bimetallic catalysts with sulfided bimetallic catalysts, Harnos et al. suggest that non-sulfided catalysts may be a valuable alternative due to their comparable activity and higher stability than the corresponding sulfided catalyst [29]. As an alternative to the above-mentioned catalysts, phosphide, carbide, and nitride catalysts have also been developed [18]. Table 3 resumes the results obtained in the DO process of several triglycerides and model compounds using different metal catalysts.

In all cases reported, it is evident that the choice of the active phase is as much important as the choice of the support. Snare et al. have correlated the increased activity of their catalyst supported on activated carbon with its high surface area, leading to lower deactivation via sintering and coking [16]. The beneficial effect of a support with high superficial area was also reported by Wang et al. in the hydrotreatment of soybean oil over NiMo carbide catalysts. They observed that the best conversion (100%) and diesel selectivity (97%) were achieved with the lab-made NiMo/Al-SBA-15 (zeolite SBA-15 enriched with Al), which has the highest surface area and the largest porosity [30]. The correlation between support surface area and catalyst activity has been observed by several authors [31][32][33][34]. The acidity of the support is another parameter that can affect the deoxygenation reaction. Peng et al., in the DO of palmitic acid over Pd, Pt, and Ni supported on ZrO2, Al2O3, HZSM-5 (hydrogen form of zeolite Socony Mobil-5), HBEA (hydrogen form of β-zeolite) and C, reported that metal supported on a support with weak or medium acidity, such as ZrO2 and zeolites, showed increased catalytic activity [35]. Furthermore, in another work, they correlate the increased activity of catalysts supported on ZrO2 with its reducible oxide properties which, through oxygen vacancies, actively participate in the reaction by adsorbing oxygenated compounds [36].

Table 3. Catalytic deoxygenation of vegetable oils and related compounds with different catalysts.

| Type | Catalyst | Support | Feedstock | Reaction Condition | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (%) | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | P (Bar) | T (h) | |||||||

| Sulfided | NiMo, CoMo, NiW | Al2O3, B2O3-Al2O3 | Waste cooking oil | 250–350 | 70 | 3 | 100 | 87% n-C15-C18 7.5% i-C 1 |

[37] |

| NiMo | SiO2, Al2O3, HY 2, HZSM-5 3, SiO2-Al2O3 | Jatropha oil, palm oil, canola oil | 350 | 40 | LHSV 4 = 7.6 h−1 | 100 | 90% n-C11-C20 | [38] | |

| NiW NiMo |

SiO2-Al2O3 Al2O3 |

Waste soybean oil, refinery oil | 340–380 | 50 | LHSV = 2.4 h−1 | >99 | 96–83% n-C15-C18 (NiMo) 79–43% n-C15-C18 (NiW) | [39] | |

| NiMo NiW |

Al2O3 TiO2, ZrO2 |

Rapeseed oil, sunflower oil, palm oil, tall oil + atmospheric gas oil | 320–360 | 20–110 | LHSV = 1.0 h−1 | 100 | 2–4% i-C15-C18 84–91% n-C15-C18 |

[40] | |

| NiMo | Al2O3 | Palm oil | 270–420 | 15–80 | LHSV = 0.25–5 h−1 | 100 | 96% n-C15-C18 | [41] | |

| Reduced | Ni | SiO2; Al2O3; SAPO-11 5; HZSM-5; HY | Methyl palmitate | 220 | 20 | 6 | 99.8 | 3% i-C15-C16 87% n-C15-C16 |

[42] |

| Ni | SiO2; Al2O3; HZSM-5; | Stearic acid | 260–290 | 8 | 6 | 100 | 90% n-C17 1.5% n-C18 |

[43] | |

| Ni | HPW 6/Al2O3 | Jatropha oil | 320–380 | 33 | LHSV = 1.0 h−1 | 99.8 | 85.5% n-C15-C18 | [44] | |

| CoMo 7 | Al2O3 | Sunflower oil | 300–380 | 40–60 | LHSV = 1.0 h−1 | 100 | 83–89% n-C15-C18 | [45] | |

| CoMo | Al2O3 | Sunflower oil | 300–380 | 20–80 | LHSV = 1.0 h−1 | 100 | 69.5–73% n-C11-C19 25–44.5% i-C |

[46] | |

| Noble | Pd | Al2O3 | Stearic acid | 350 | 6–14 (H2 or N2) | 3 | 100 | 9% n-C18 91% n-C17 |

[47] |

| Pd | SBA-15 8 | Stearic acid | 300 | 17 (5%H2/Ar) | 5 | 96 | 98% n-C17 | [48] | |

| Ru, Pd, Pt, Rh | HZSM-5 | Stearic acid, methyl stearate | 160–260 | 30 | 8 | 90.8 | 77% n-C17-C18 | [49] | |

| Pd | C | Palmitic acid, stearic acid | 300 | 17 (5%H2/Ar) | 3 | 98 | >99% n-C15-C17 | [50] | |

| Pt, Pt-Re | SiO2, SiO2-Al2O3, HZSM-5, USY 9, BEA 10, HY, H-MOR 11, PER 12, L 13 | Jatropha oil | 270 | 65 (91%H2/Ar) | 12 | 100 | 95% n-C10-C20 | [51] | |

| Carbide, Phosphide, Nitride | W2C, Mo2C | CNF 14 | Oleic acid | 350 | 50 | 5 | 100 | 85% n-C18 | [52] |

| Mo2C | AC 15 | Methyl palmitate | 280 | 10 | 4 | 100 | 4% n-C15 91% n-C16 |

[53] | |

| Mo2C | RGO 16 | Oleic acid (OA), soybean oil (SO) | 350 | 50 | LHSV = 2 h−1 | 95 (OA), 71.8 (SO) | 85% n-C18 | [54] | |

| Mo2C | CNF | Methyl palmitate | 260 | 25 | 3 | 98 | 91.5% n-C16 | [55] | |

| Ni2P | SiO2 | Methyl laurate | 300 | 20 | WHSV 17 = 5.2 h−1 | 97.2 | 84% n-C11 15% n-C12 |

[56] | |

| NiP | AC | Palmitic acid | 350 | 1 (5%H2/Ar) | 2.5 | 99.4 | 11% n-C11-C14 74% n-C15 |

[57] | |

| Mo2N, VN,WN | Al2O3 | Oleic acid, canola oil | 380–410 | 71.5 | GHSV 18 = 1850 h−1 | 97 | 84% hydrocarbons fuel | [58] | |

| NiMoC, NiMoN | ZSM-5 | Soybean oil | 360–450 | 45 | LHSV = 1 h−1 | 100 | 50 wt% hydrocarbon fuel | [59] | |

| MoC, MoN, MoP | Al2O3 | Rapeseed oil | 350–390 | 55 | LHSV = 1–4 h−1 | -- | 73–80% diesel-like fuel | [60] | |

1 i-C = isoalkanes; 2 HY = hydrogen form of zeolite Y; 3 HZSM-5 = hydrogen form of zeolite Socony Mobil-5; 4 LHSV = liquid hourly space velocity; 5 SAPO-11 = medium-pore silicoaluminophosphate molecular sieve; 6 HPW = phosphotungstic acid; 7 commercial; 8 SBA-15 = Santa Barbara amorphous-15; 9 USY = ultrastable zeolite Y; 10 BEA = beta zeolite; 11 MOR = hydrogen form of mordenite zeolite; 12 FER = ferrierite zeolite; 13 L = zeolite type L; 14 CNF = carbon nanofibers; 15 AC = activated carbon; 16 RGO = reduced graphene oxide; 17 WHSV = weight hourly space velocity; 18 GHSV = gas hourly space velocity.

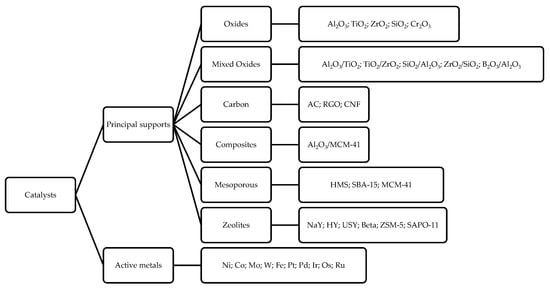

In another work, Peng et al. analyzed the DO reaction of oil extracted from microalgae using two Ni-based catalysts supported on H-ZSM5 and H-β. With Ni/H-ZSM5 the reaction shows a high degree of cracking (43%) and coke formation [61]; the authors correlate these phenomena to the higher concentration of Bronsted acid sites of this catalyst that greatly favor cracking. They found that when increasing the zeolite’s Si/Al ratio (as the Si/Al ratio increases, the zeolite’s acidity decreases) cracking and coke formation decrease, but at the same time, the conversion decreased too. The acidity–cooking correlation has also been reported by Ardiyanti et al. in the upgrading of fast pyrolysis oil using NiCu/γ-Al2O3 and NiCu/δ-Al2O3 [62]. They observed that using δ-Al2O3 (less acidic than γ-Al2O3) leads to a minor amount of coke. Adequate acidity is necessary for triglycerides conversion, and it is necessary to avoid a too high acidity, as it favors cracking reactions and coke formation. In addition, the support can also influence the HDO, DCO/DCO2 reaction selectivity [35][36][61]. As observed by Twaiq et al., the size of the pores is also important. By studying the cracking reaction of palm oil over various zeolites (HZSM-5, β-Zeolite, USY), ref. [63] the authors suggest that the support pore size strongly affects the hydrocarbon distribution in the diesel mixture; USY (ultrastable Y) zeolite, which has a larger pore size, leads to less cracking (gasoline range 4–17%) than HZSM-5 zeolite (gasoline range 17–28%). The same results are obtained in aromatization, leading to a lower formation of aromatic hydrocarbon (20–38% for HZSM-5 versus 3–13% for USY). A sufficiently large pore size would tend to minimize cracking, thus leading to a greater diesel selectivity. Indeed, mesoporous materials are experiencing increasing interest as the mesoporous pores of these materials allow for easier diffusion of the substrate, which implies less coking and cracking reactions [59][63]. A scheme reassuming the principal catalysts and supports used in DO reaction is reported in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Principal metal catalysts and supports used in DO reaction.

2.2. Temperature

Temperature is a very important variable in the catalytic deoxygenation reaction, as it can significantly influence rate, conversion, hydrocarbon distribution, cracking, and to a lesser extent, reaction selectivity. Snare et al., studying the DO of ethyl stearate over Pd/C, observed that an increase in temperature from 300 to 360 °C leads to a fourfold increase in conversion [64]. Similar results were reported by Madsen et al. in the oleic acid/tripalmitin mixture (1:3) hydrotreating in H2 atmosphere over Pt/Al2O3 [27]. The authors showed an increase in conversion from 6% at 250 °C to 100% at 325 °C. An increase in conversion with temperature has also been observed by Maki-Arvela et al., but more interestingly, they reported that an increase in temperature also leads to a higher degree of dehydrogenation as the n-heptadecane/n-heptadecene ratio decreases [65]. The effect of the reaction temperature on the dehydrogenation reaction was also observed by Cheng et al. in the hydrotreating of soybean oil over NiMo/HY (HY = hydrogen form of the zeolite Y) for the production of jet biofuel [66]. In their work, they reported an increase in the formation of aromatic hydrocarbons as the temperature rises. In fact, at temperatures above 390 °C, the aromatic content increased from 17.6 to 28.7%. A similar trend was also observed by Li et al. [67]. The temperature also has a great influence on the range of hydrocarbon distributions in the biofuel. Verma et al. found that a temperature increase (375–450 °C) leads to an increase in the distribution of hydrocarbons in the kerosene range (425 °C), indicating an improved cracking reaction with the temperature and, as consequences, they also observed an increase in isomerization selectivity as the temperature increases [68]. Working at 375 °C led to higher diesel selectivity (85–96%); if higher temperatures were used (450 °C), the cracking is prevailing, leading to a decrease in the kerosene range in favor of gaseous products. Similar results were observed by Srifa et al. [41]. The correlation between cracking and temperature has also been observed by Pinto et al. in the DO of pomace oil olives [69]. As the temperature increased, an increase in light hydrocarbons and a decrease in heavy fractions was observed. This phenomenon improves with longer reaction time. Moreover, analyzing the gas phase of the reaction, they observed that as the temperature increases, the presence of gases such as methane, ethane, and other gaseous hydrocarbons increases, indicating a greater degree of cracking. They also observed an increase in CO and CO2 concentration, which seems to indicate that an increase in temperature leads to higher selectivity of reaction towards DCO/DCO2, and this is in agreement with the endothermic nature of these reactions. On the other hand, HDO is exothermic and therefore favored at lower temperatures [70][71]. Liu et al. investigated the isomerization of palm oil over Ni/SAPO-11 (medium-pore silicoaluminophosphate molecular sieve), observing that low reaction temperatures (320 °C) yield low isomerization (in favor of a higher selectivity towards n-alkanes in the diesel range), while higher temperatures considerably increase isomerization activity, often accompanied by a considerable cracking. Isomerization selectivity greater than 80% and a liquid hydrocarbon yield of 70% were obtained [72]. Considering all the above reported, it is evident that temperature control is crucial in order to obtain the desired type of fuel. Moreover, the temperature also plays an important role in the deactivation of the catalyst. Higher temperatures can lead to catalysts sintering, increasing the formation of aromatics and coke, which leads to rapid deactivation of the catalyst [73].

2.3. Reaction Atmosphere

The catalytic deoxygenation reaction can be performed in an inert atmosphere, typically He and Ar, in a hydrogen atmosphere, or even in an H2/He or Ar mixture. The DO reaction can be greatly influenced by the type and the pressure of the gas used. Snare et al. conducted the reaction on different substrates (oleic acid, linoleic acid, and methyl oleate) over Pd/C, varying the reaction atmosphere. Pure H2, pure Ar, and H2–Ar mixture were used. Working in an H2-rich atmosphere, where the deoxygenation reaction is strongly promoted, they observed, for each substrate used, a greater conversion of hydrocarbons [74]. Similar results were obtained in the hydrotreating of ethyl stearate over Pd/C [75]. The authors observed that an H2-rich atmosphere promotes the hydrogenation of unsaturated species and therefore increases the concentration of saturated hydrocarbons in the biofuel. Kubickova et al. showed a lower number of aromatic hydrocarbons and a high concentration of saturated hydrocarbons in the H2 atmosphere, but more interesting, they also reported better conversion and catalyst TOF (turnover frequency) in 5%H2/Ar atmosphere [76]. In addition, the authors showed that pH2 affects the reaction; higher pressure leads to a lesser amount of unsaturated hydrocarbon compound. Particularly interesting results were reported by Santillan-Jimenez et al. in the DO of stearic acid and tristearin with Pd(5%)/C and Ni(20%)/C in pure H2, pure N2, and 10% miH2/N2 [77]. They observed different the catalysts’ activity depending on the atmosphere used; Ni/C is more promising in pure H2, while Pd/C is better in 10%H2/N2. In conjunction with the reaction atmosphere, pH2 can greatly influence the catalytic deoxygenation reaction. In methyl oleate, hydrotreatment over Pd/SBA-15, Lee and co-workers reported that an increase in pressure from 25 to 60 bar leads to a significant improvement in C15–C18 conversion and selectivity (up to 100% conversion and 70% selectivity C15–C18) [78]. A further increase from 60 to 80 bar leads to a decrease in conversion, and this is due to increased competition between the substrate and H2 for the catalyst’s active sites [78][79]. The positive effect of partial hydrogen pressure has also been reported by Nimkarde et al. in the DO of Karanja oil over NiMo and CoMo catalysts [80]. By increasing the pressure from 15 to 30 bar the conversion increased from 62.1 to 88.4% over NiMo and from 60.1 to 85.6% over CoMo. Sotelo-Boyas et al. observed a progressive increase in conversion and selectivity to HDO by increasing the pressure from 50 to 110 bar. A decrease in the percentage of heavy fractions in favor of light C5–C12 fractions, indicating that high pressures seem to favor a higher degree of cracking, was also observed [81]. This seems to be in contrast to what was observed by Yang et al. studying the DO of a mixture of C18 acids over sulfided NiW/SiO2-Al2O3. Varying the pressure from 20–80 bar, the C3–C11 light fraction yield decreased as the pressure increased, while the diesel yield increased up to 40 bar and then decreased at higher pressures [82]. The authors suggested that high pressure restrains cracking reactions and explained this with the Le Chatelier Principle. They also observed a decrease in DCO/DCO2 selectivity and a higher prevalence of HDO, at higher pressure, due to the major amount of hydrogen available for HDO. Higher pressure tends also to inhibit isomerization due a higher amount of H2 adsorbed on the catalyst sites used for isomerization. Anand et al. studied the DO of jatropha oil by varying the P from 20 to 90 bar [83]. Their work shows that an increase in conversion from 91 to 98% by increasing the pressure from 40 to 90 bar but a drastic reduction in conversion (31%) by working at pressures of 20 bar. Despite the high conversion obtained at 40 bar, the biofuel has a high concentration of oligomerized product (20% > C18), which decreases by increasing the pressure. The authors report that under their conditions the optimum pressure value is 80 bar.

2.4. Other Parameters

In addition to the previously discussed parameters, there are other variables that can influence the catalytic deoxygenation reaction such as the solvent, substrate, and reactor. Maki-Arvela et al. have observed a different reaction selectivity of their catalyst using free fatty acids (FFA) or methyl esters [75]. Using FFA, the reaction proceeds via DCO2, while using the corresponding methyl esters it appears that the reaction proceeds via DCO. In addition, the authors have also observed that compounds with longer chains tend to retard the reaction rate. Morgan et al., studying the DO of triolein and soybean oil under an inert atmosphere over a hydrotalcite-type catalyst, observed high cracking and coking activity only with soybean oil, which suggests that a higher degree of substrate unsaturation tends to favor cocking and cracking [84]. In addition, as observed by Kiatkittipong and co-workers, in the DO of CPO (crude palm oil), DPO (degummed palm oil), and PFAD (palm fatty acids distillate), the degree of substrate pre-treatment also seems to influence the reaction [85]. Using PFAD, the reaction requires less drastic conditions, and a better hydrocarbon yield is obtained. In addition, the authors also observed that Pd/C is more promising when working with PFAD, while sulfided NiMo/γ-Al2O3 is preferred with triglyceride-type substrates. The catalytic deoxygenation reaction can be performed in batch, semi-batch, or continuous reactors. Compared to continuous reactors, batch reactors allow for preliminary studies to be made to optimize reaction conditions and to generate kinetic data in an easy and economical manner [86]. The use of continuous and semi-batch reactors has the advantage of purging the reactor of COx formed during the reaction, and this has a dual advantage; one is to shift the balance of the reaction towards the products and the other is to avoid the poisoning of the catalysts by CO adsorption [79][87]. By comparing the same reaction conditions with the same catalyst (Pd/C), Snare et al. observed higher productivity in the semi-batch mode compared to the continuous reactor by attributing the cause to the mass transfer limitations in the fixed-bed reactor [74]. The solvent used can also slightly influence the catalytic deoxygenation reaction. Gosselink et al. evaluated the effect of the solvent by comparing n-decane, n-dodecane, and mesitylene and reported that n-decane and mesitylene led to better catalytic activity than n-dodecane [12]. Low-boiling solvents guarantee better activity [57][62]. The solvent can also modulate the activity of the catalysts, since Pt/C is more active than Pd/C in the DO of FFA in aqueous media while the opposite is the case in organic media [88][89].

References

- Mehrpooya, M.; Ghorbani, B.; Abedi, H. Biodiesel production integrated with glycerol steam reforming process, solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) power plant. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 206, 112467.

- Wang, W.C.; Thapaliya, N.; Campos, A.; Stikeleather, L.F.; Roberts, W.L. Hydrocarbon fuels from vegetable oils via hydrolysis and thermo-catalytic decarboxylation. Fuel 2012, 95, 622–629.

- Shi, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Tian, S. Catalytic deoxygenation of methyl laurate as a model compound to hydrocarbons on nickel phosphide catalysts: Remarkable support effect. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 118, 161–170.

- Jakkula, J.; Niemi, V.; Nikkonen, J.; Purola, V.; Myllyoja, J.; Aalto, P.; Lehtonen, J.; Alopaeus, V. Process for Producing a Hydrocarbon Component of Biological Origin. U.S. Patent 7,232,935 B2, 19 June 2007.

- Vonortas, A.; Papayannakos, N. Comparative analysis of biodiesel versus green diesel. WIREs Energy Environ. 2014, 3, 3–23.

- Na, J.G.; Yi, B.E.; Kim, J.N.; Yi, K.B.; Park, S.Y.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.N.; Ko, C.H. Hydrocarbon production from decarboxylation of fatty acid without hydrogen. Catal. Today 2010, 156, 44–48.

- Knothe, G.; Dunn, R.O.; Bagby, M.O. Biodiesel: The Use of Vegetable Oils and Their Derivatives as Alternative Diesel Fuels. ACS Symp. Ser. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 666, 172–208.

- Han, J.; Elgowainy, A.; Cai, H.; Wang, M.Q. Life-cycle analysis of bio-based aviation fuels. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 150, 447–456.

- Knothe, G. Biodiesel and renewable diesel: A comparison. Prog. Energy. Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 364–373.

- Galadima, A.; Muraza, O. Hydroisomerization of sustainable feedstock in biomass-to-fuel conversion: A critical review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2015, 39, 741–759.

- Gosselink, R.W.; Hollak, S.A.W.; Chang, S.W.; Van Haveren, J.; De Jong, K.P.; Bitter, J.H.; Van Es, D.S. Reaction Pathways for the Deoxygenation of Vegetable Oils and Related Model Compounds. ChemSusChem 2013, 6, 1576–1594.

- Veriansyah, B.; Han, J.Y.; Kim, S.K.; Hong, S.A.; Kim, Y.J.; Lim, J.S.; Shu, Y.W.; Oh, S.G.; Kim, J. Production of renewable diesel by hydroprocessing of soybean oil: Effect of catalysts. Fuel 2012, 94, 578–585.

- Kubička, D.; Bejblová, M.; Vlk, J. Conversion of vegetable oils into hydrocarbons over CoMo/MCM-41 catalysts. Top. Catal. 2010, 53, 168–178.

- Rogers, K.A.; Zheng, Y. Selective Deoxygenation of Biomass-Derived Bio-oils within Hydrogen-Modest Environments: A Review and New Insights. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 1750–1772.

- Snåre, M.; Kubičková, I.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Eränen, K.; Murzin, D.Y. Heterogeneous catalytic deoxygenation of stearic acid for production of biodiesel. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 5708–5715.

- Şenol, O.I.; Viljava, T.R.; Krause, A.O.I. Hydrodeoxygenation of aliphatic esters on sulphided NiMo/γ-Al2O3 and CoMo/γ-Al2O3 catalyst: The effect of water. Catal. Today 2005, 106, 186–189.

- Li, X.; Luo, X.; Jin, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, A.; Xie, J. Heterogeneous sulfur-free hydrodeoxygenation catalysts for selectively upgrading the renewable bio-oils to second generation biofuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3762–3797.

- Wang, C.; Tian, Z.; Wang, L.; Xu, R.; Liu, Q.; Qu, W.; Ma, H.; Wang, B. One-step hydrotreatment of vegetable oil to produce high quality diesel-range alkanes. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1974–1983.

- Wang, W.C.; Tao, L. Bio-jet fuel conversion technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 801–822.

- Khan, S.; Kay Lup, A.N.; Qureshi, K.M.; Abnisa, F.; Wan Daud, W.M.A.; Patah, M.F.A. A review on deoxygenation of triglycerides for jet fuel range hydrocarbons. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 140, 1–24.

- Donnis, B.; Egeberg, R.G.; Blom, P.; Knudsen, K.G. Hydroprocessing of bio-oils and oxygenates to hydrocarbons. Understanding the reaction routes. Top. Catal. 2009, 52, 229–240.

- Kubička, D.; Kaluža, L. Deoxygenation of vegetable oils over sulfided Ni, Mo and NiMo catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 372, 199–208.

- Horáček, J.; Tišler, Z.; Rubáš, V.; Kubička, D. HDO catalysts for triglycerides conversion into pyrolysis and isomerization feedstock. Fuel 2014, 121, 57–64.

- Kubička, D.; Horáček, J. Deactivation of HDS catalysts in deoxygenation of vegetable oils. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2011, 394, 9–17.

- Şenol, O.I.; Viljava, T.R.; Krause, A.O.I. Effect of sulphiding agents on the hydrodeoxygenation of aliphatic esters on sulphided catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2007, 326, 236–244.

- Madsen, A.T.; Ahmed, E.H.; Christensen, C.H.; Fehrmann, R.; Riisager, A. Hydrodeoxygenation of waste fat for diesel production: Study on model feed with Pt/alumina catalyst. Fuel 2011, 90, 3433–3438.

- Morgan, T.; Grubb, D.; Santillan-Jimenez, E.; Crocker, M. Conversion of triglycerides to hydrocarbons over supported metal catalysts. Top. Catal. 2010, 53, 820–829.

- Harnos, S.; Onyestyák, G.; Kalló, D. Hydrocarbons from sunflower oil over partly reduced catalysts. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2012, 106, 99–111.

- Wang, H.; Yan, S.; Salley, S.O.; Simon Ng, K.Y. Support effects on hydrotreating of soybean oil over NiMo carbide catalyst. Fuel 2013, 111, 81–87.

- Kaewpengkrow, P.; Atong, D.; Sricharoenchaikul, V. Catalytic upgrading of pyrolysis vapors from Jatropha wastes using alumina, zirconia and titania based catalysts. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 163, 262–269.

- Taufiqurrahmi, N.; Mohamed, A.R.; Bhatia, S. Nanocrystalline zeolite beta and zeolite y as catalysts in used palm oil cracking for the production of biofuel. J. Nanopart. Res. 2011, 13, 3177–3189.

- Yenumala, S.R.; Maity, S.K.; Shee, D. Hydrodeoxygenation of karanja oil over supported nickel catalysts: Influence of support and nickel loading. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 3156–3165.

- Asikin-Mijan, N.; Lee, H.V.; Abdulkareem-Alsultan, G.; Afandi, A.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H. Production of green diesel via cleaner catalytic deoxygenation of Jatropha curcas oil. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1048–1059.

- Peng, B.; Zhao, C.; Kasakov, S.; Foraita, S.; Lercher, J.A. Manipulating Catalytic Pathways: Deoxygenation of Palmitic Acid on Multifunctional Catalysts. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2013, 19, 4732–4741.

- Peng, B.; Yuan, X.; Zhao, C.; Lercher, J.A. Stabilizing catalytic pathways via redundancy: Selective reduction of microalgae oil to alkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9400–9405.

- Toba, M.; Abe, Y.; Kuramochi, H.; Osako, M.; Mochizuki, T.; Yoshimura, Y. Hydrodeoxygenation of waste vegetable oil over sulfide catalysts. Catal. Today 2011, 164, 533–537.

- Liu, Y.; Sotelo-Boyás, R.; Murata, K.; Minowa, T.; Sakanishi, K. Hydrotreatment of vegetable oils to produce bio-hydrogenated diesel and liquefied petroleum gas fuel over catalysts containing sulfided Ni-Mo and solid acids. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 4675–4685.

- Tiwari, R.; Rana, B.S.; Kumar, R.; Verma, D.; Kumar, R.; Joshi, R.K.; Garg, M.O.; Sinha, A.K. Hydrotreating and hydrocracking catalysts for processing of waste soya-oil and refinery-oil mixtures. Catal. Commun. 2011, 12, 559–562.

- Mikulec, J.; Cvengroš, J.; Joríková, Ľ.; Banič, M.; Kleinová, A. Second generation diesel fuel from renewable sources. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 917–926.

- Srifa, A.; Faungnawakij, K.; Itthibenchapong, V.; Viriya-empikul, N.; Charinpanitkul, T.; Assabumrungrat, S. Production of bio-hydrogenated diesel by catalytic hydrotreating of palm oil over NiMoS2/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 158, 81–90.

- Zuo, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, T.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q. Hydrodeoxygenation of methyl palmitate over supported Ni catalysts for diesel-like fuel production. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 3747–3755.

- Kumar, P.; Yenumala, S.R.; Maity, S.K.; Shee, D. Kinetics of hydrodeoxygenation of stearic acid using supported nickel catalysts: Effects of supports. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2014, 471, 28–38.

- Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Zhou, G.; Tian, W.; Rong, L. A cleaner process for hydrocracking of jatropha oil into green diesel. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2013, 44, 221–227.

- Krár, M.; Kovács, S.; Kalló, D.; Hancsók, J. Fuel purpose hydrotreating of sunflower oil on CoMo/Al2O3 catalyst. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 9287–9293.

- Krár, M.; Kasza, T.; Kovács, S.; Kalló, D.; Hancsók, J. Bio gas oils with improved low temperature properties. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 886–892.

- Berenblyum, A.S.; Podoplelova, T.A.; Shamsiev, R.S.; Katsman, E.A.; Danyushevsky, V.Y. On the mechanism of catalytic conversion of fatty acids into hydrocarbons in the presence of palladium catalysts on alumina. Pet. Chem. 2011, 51, 336–341.

- Lestari, S.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Eränen, K.; Beltramini, J.; Max Lu, G.Q.; Murzin, D.Y. Diesel-like hydrocarbons from catalytic deoxygenation of stearic acid over supported pd nanoparticles on SBA-15 catalysts. Catal. Lett. 2010, 134, 250–257.

- Chen, J.; Xu, Q. Hydrodeoxygenation of biodiesel-related fatty acid methyl esters to diesel-range alkanes over zeolite-supported ruthenium catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 7239–7251.

- Lestari, S.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Simakova, I.; Beltramini, J.; Lu, G.Q.M.; Murzin, D.Y. Catalytic deoxygenation of stearic acid and palmitic acid in semibatch mode. Catal. Lett. 2009, 130, 48–51.

- Murata, K.; Liu, Y.; Inaba, M.; Takahara, I. Production of synthetic diesel by hydrotreatment of jatropha oils using Pt-Re/H-ZSM-5 catalyst. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 2404–2409.

- Hollak, S.A.W.; Gosselink, R.W.; Van Es, D.S.; Bitter, J.H. Comparison of tungsten and molybdenum carbide catalysts for the hydrodeoxygenation of oleic acid. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2837–2844.

- Han, J.; Duan, J.; Chen, P.; Lou, H.; Zheng, X. Molybdenum Carbide-Catalyzed Conversion of Renewable Oils into Diesel-like Hydrocarbons. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2577–2583.

- Kim, S.K.; Yoon, D.; Lee, S.C.; Kim, J. Mo2C/graphene nanocomposite as a hydrodeoxygenation catalyst for the production of diesel range hydrocarbons. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 3292–3303.

- Qin, Y.; Chen, P.; Duan, J.; Han, J.; Lou, H.; Zheng, X.; Hong, H. Carbon nanofibers supported molybdenum carbide catalysts for hydrodeoxygenation of vegetable oils. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 17485–17491.

- Chen, J.; Shi, H.; Li, L.; Li, K. Deoxygenation of methyl laurate as a model compound to hydrocarbons on transition metal phosphide catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 144, 870–884.

- Xin, H.; Guo, K.; Li, D.; Yang, H.; Hu, C. Production of high-grade diesel from palmitic acid over activated carbon-supported nickel phosphide catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 187, 375–385.

- Monnier, J.; Sulimma, H.; Dalai, A.; Caravaggio, G. Hydrodeoxygenation of oleic acid and canola oil over alumina-supported metal nitrides. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 382, 176–180.

- Wang, H.; Yan, S.; Salley, S.O.; Ng, K.Y.S. Hydrocarbon fuels production from hydrocracking of soybean oil using transition metal carbides and nitrides supported on ZSM-5. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 10066–10073.

- Horáček, J.; Akhmetzyanova, U.; Skuhrovcová, L.; Tišler, Z.; de Paz Carmona, H. Alumina-supported MoNx, MoCx and MoPx catalysts for the hydrotreatment of rapeseed oil. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 263, 118328.

- Peng, B.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Lercher, J.A. Towards Quantitative Conversion of Microalgae Oil to Diesel-Range Alkanes with Bifunctional Catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2072–2075.

- Ardiyanti, A.R.; Khromova, S.A.; Venderbosch, R.H.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Heeres, H.J. Catalytic hydrotreatment of fast-pyrolysis oil using non-sulfided bimetallic Ni-Cu catalysts on a δ-Al2O3 support. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 117–118, 105–117.

- Twaiq, F.A.; Zabidi, N.A.M.; Bhatia, S. Catalytic conversion of palm oil to hydrocarbons: Performance of various zeolite catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 3230–3237.

- Snåre, M.; Kubičková, I.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Eränen, K.; Wärnå, J.; Murzin, D.Y. Production of diesel fuel from renewable feeds: Kinetics of ethyl stearate decarboxylation. Chem. Eng. J. 2007, 134, 29–34.

- Mäki-Arvela, P.; Rozmysłowicz, B.; Lestari, S.; Simakova, O.; Eränen, K.; Salmi, T.; Murzin, D.Y. Catalytic deoxygenation of tall oil fatty acid over palladium supported on mesoporous carbon. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 2815–2825.

- Cheng, J.; Li, T.; Huang, R.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. Optimizing catalysis conditions to decrease aromatic hydrocarbons and increase alkanes for improving jet biofuel quality. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 158, 378–382.

- Li, T.; Cheng, J.; Huang, R.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. Conversion of waste cooking oil to jet biofuel with nickel-based mesoporous zeolite Y catalyst. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 197, 289–294.

- Verma, D.; Rana, B.S.; Kumar, R.; Sibi, M.G.; Sinha, A.K. Diesel and aviation kerosene with desired aromatics from hydroprocessing of jatropha oil over hydrogenation catalysts supported on hierarchical mesoporous SAPO-11. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2015, 490, 108–116.

- Pinto, F.; Varela, F.T.; Gonçalves, M.; Neto André, R.; Costa, P.; Mendes, B. Production of bio-hydrocarbons by hydrotreating of pomace oil. Fuel 2014, 116, 84–93.

- Huber, G.W.; O’Connor, P.; Corma, A. Processing biomass in conventional oil refineries: Production of high quality diesel by hydrotreating vegetable oils in heavy vacuum oil mixtures. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2007, 329, 120–129.

- Kim, S.K.; Brand, S.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J. Production of renewable diesel by hydrotreatment of soybean oil: Effect of reaction parameters. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 228, 114–123.

- Liu, Q.; Zuo, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Ma, L. Hydrodeoxygenation of palm oil to hydrocarbon fuels over Ni/SAPO-11 catalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 2014, 35, 748–756.

- Patel, M.; Kumar, A. Production of renewable diesel through the hydroprocessing of lignocellulosic biomass-derived bio-oil: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 1293–1307.

- Snåre, M.; Kubičková, I.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Chichova, D.; Eränen, K.; Murzin, D.Y. Catalytic deoxygenation of unsaturated renewable feedstocks for production of diesel fuel hydrocarbons. Fuel 2008, 87, 933–945.

- Mäki-Arvela, P.; Kubickova, I.; Snåre, M.; Eränen, K.; Murzin, D.Y. Catalytic Deoxygenation of Fatty Acids and Their Derivatives. Energy Fuels 2007, 21, 30–41.

- Kubičková, I.; Snåre, M.; Eränen, K.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Murzin, D.Y. Hydrocarbons for diesel fuel via decarboxylation of vegetable oils. Catal. Today 2005, 106, 197–200.

- Santillan-Jimenez, E.; Morgan, T.; Lacny, J.; Mohapatra, S.; Crocker, M. Catalytic deoxygenation of triglycerides and fatty acids to hydrocarbons over carbon-supported nickel. Fuel 2013, 103, 1010–1017.

- Lee, S.P.; Ramli, A. Methyl oleate deoxygenation for production of diesel fuel aliphatic hydrocarbons over Pd/SBA-15 catalysts. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7, 149.

- Immer, J.G.; Kelly, M.J.; Lamb, H.H. Catalytic reaction pathways in liquid-phase deoxygenation of C18 free fatty acids. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 375, 134–139.

- Nimkarde, M.R.; Vaidya, P.D. Toward Diesel Production from Karanja Oil Hydrotreating over CoMo and NiMo Catalysts. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 3107–3112.

- Sotelo-Boyás, R.; Liu, Y.; Minowa, T. Renewable diesel production from the hydrotreating of rapeseed oil with Pt/zeolite and NiMo/Al2O3 catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 2791–2799.

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, G. Hydrotreating of C18 fatty acids to hydrocarbons on sulfided NiW/SiO2-Al2O3. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 116, 165–174.

- Anand, M.; Sinha, A.K. Temperature-dependent reaction pathways for the anomalous hydrocracking of triglycerides in the presence of sulfided Co-Mo-catalyst. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 126, 148–155.

- Morgan, T.; Santillan-Jimenez, E.; Harman-Ware, A.E.; Ji, Y.; Grubb, D.; Crocker, M. Catalytic deoxygenation of triglycerides to hydrocarbons over supported nickel catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 189–190, 346–355.

- Kiatkittipong, W.; Phimsen, S.; Kiatkittipong, K.; Wongsakulphasatch, S.; Laosiripojana, N.; Assabumrungrat, S. Diesel-like hydrocarbon production from hydroprocessing of relevant refining palm oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 116, 16–26.

- Noriega, A.K.; Tirado, A.; Méndez, C.; Marroquín, G.; Ancheyta, J. Hydrodeoxygenation of vegetable oil in batch reactor: Experimental considerations. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 1670–1683.

- Mäki-Arvela, P.; Snåre, M.; Eränen, K.; Myllyoja, J.; Murzin, D.Y. Continuous decarboxylation of lauric acid over Pd/C catalyst. Fuel 2008, 87, 3543–3549.

- Fu, J.; Lu, X.; Savage, P.E. Catalytic hydrothermal deoxygenation of palmitic acid. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 311–317.

- Fu, J.; Lu, X.; Savage, P.E. Hydrothermal Decarboxylation and Hydrogenation of Fatty Acids over Pt/C. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 481–486.

More

Information

Subjects:

Green & Sustainable Science & Technology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.4K

Revisions:

4 times

(View History)

Update Date:

13 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No