| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shankargouda Patil | + 1273 word(s) | 1273 | 2021-12-30 04:32:20 | | | |

| 2 | Yvaine Wei | Meta information modification | 1273 | 2022-01-11 02:56:40 | | |

Video Upload Options

Stem cell therapy is an evolving treatment strategy in regenerative medicine. Recent studies report stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth could complement the traditional mesenchymal stem cell sources. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth exhibit mesenchymal characteristics with multilineage differentiation potential. Mesenchymal stem cells are widely investigated for cell therapy and disease modeling.

1. Introduction

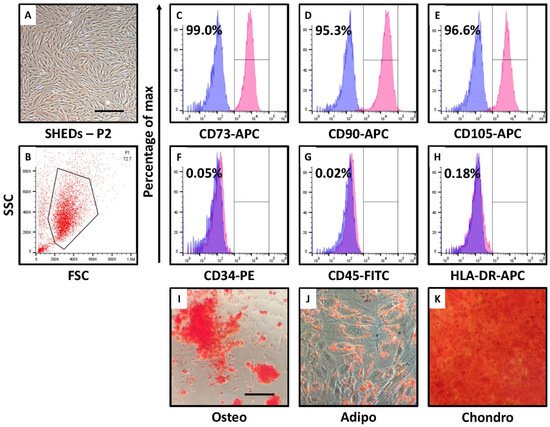

2. SHEDs Show MSC-like Morphology, Cell Surface Marker Expression, and Trilineage Differentiation

3. Research Findings

In regenerative medicine, cell therapy is regarded as a promising strategy to treat the diseases which are caused by cell death. In recent years, the development of treatment methods has been a great hope. However, currently, there are many challenges for implementing stem cell-based therapy widely. One of the most important challenge is the complete functioning and fate of stem cells in the transplanted system. There are many factors which determine the fate of stem cells and the prime important one is the microenvironment. Recently it has been shown that, the tissue microenvironment can determine the proliferation, cell survival, and even de-differentiation of transplanted stem cells [15].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)due to their ability to differentiate into cells of different mesenchymal origin, it is widely under investigation in cell therapy. SHEDs obtained from the pulp of human deciduous pulp open a new avenue, due to the effortlessness of getting the samples and less ethical issues. The multilineage differentiation potential and proliferation potential of SHEDs compared to bone marrow MSCs suggests SHEDs can complement bone marrow MSCs [16]. The success of MSC based cell therapy primarily depends on factors such as status of host immune status, the microenvironment. The microenvironment factors such as inflammation, hypoxia, and extracellular matrix influence the homing and fate of transplanted MSCs [11].

The isolation of the SHEDs was carried out from the human deciduous teeth pulp and characterized. The morphological as well as cell surface marker-based characterization of SHEDs revealed mesenchymal property with a potential to differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic cell lineages. The incubation of SHEDs in nutrient deprived and low glucose medium leads to change in morphology of the cells. Although, phenotypically the cells were not showing mesenchymal morphology these cells showed, low expression of epithelial marker CD29, high expression of mesenchymal markers CD271 and pluripotent stem cell marker CD140b. These indicates the changes in cell morphology may be an adaptation to survive the low nutrient medium. Changes in cell morphology associated with low nutrients is previously reported in primary microglia and BV-2 cells [17]. CD140b is also an angiogenic mediator which might be activated due to the low glucose level [18]. It has been shown hypoxia and serum deprivation can induce angiogenesis [19]. Serum deprivation and low glucose level also reduced the differentiation potential of MSCs to osteogenic lineage.

The results suggests that nutrient deprivation leads to the cell cycle arrest in S-phase via high expression of cyclin inhibitors, low expression of cyclin along with the elevated expression of transcription factor FOXO3. FOXO3 expression is directly regulated by the nutrient sensor AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [20].

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis of energy, controls the metabolic pathways and also nutrient supply. AMPK is often known as cellular energy sensor as it can be activated by various conditions such as decrease in cellular energy levels, low glucose level, hypoxia and exposure to toxins [21]. AMPK primarily controls the balance of ATP and inhibits the anabolic pathways [22]. AMPK also regulates transcription of several metabolomic kinases. Recent studies showed the involvement of AMPK in cell polarity and cytoskeletal dynamics [23].

The research also showed that nutrient deprivation of SHEDs led to reduced proliferation, increased apoptosis, activation of stress sensing molecule AMPK and induced distinct differentiation lineages in SHEDs.

References

- Sah, J.P. Challenges of Stem Cell Therapy in Developing Country. J. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 1, 96–98.

- Prockop, D.J. Marrow Stromal Cells as Stem Cells for Nonhematopoietic Tissues. Science 1997, 276, 71–74.

- Weissman, I.L. Translating Stem and Progenitor Cell Biology to the Clinic: Barriers and Opportunities. Science 2000, 287, 1442–1446.

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage Potential of Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147.

- Govitvattana, N.; Osathanon, T.; Taebunpakul, S.; Pavasant, P. IL-6 regulated stress-induced Rex-1 expression in stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Oral Dis. 2012, 19, 673–682.

- Denu, R.A.; Hematti, P. Effects of Oxidative Stress on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Biology. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 2989076.

- Fonteneau, G.; Bony, C.; Goulabchand, R.; Maria, A.T.J.; Le Quellec, A.; Rivière, S.; Jorgensen, C.; Guilpain, P.; Noël, D. Serum-Mediated Oxidative Stress from Systemic Sclerosis Patients Affects Mesenchymal Stem Cell Function. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 988.

- Anoop, M.; Datta, I. Stem Cells Derived from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHED) in Neuronal Disorders: A Review. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 16, 535–550.

- Nakamura, S.; Yamada, Y.; Katagiri, W.; Sugito, T.; Ito, K.; Ueda, M. Stem Cell Proliferation Pathways Comparison between Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth and Dental Pulp Stem Cells by Gene Expression Profile from Promising Dental Pulp. J. Endod. 2009, 35, 1536–1542.

- Wang, S.; Qu, X.; Zhao, R.C. Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2012, 5, 19.

- Zhou, T.; Yuan, Z.; Weng, J.; Pei, D.; Du, X.; He, C.; Lai, P. Challenges and advances in clinical applications of mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 24.

- Nuschke, A.; Rodrigues, M.; Stolz, D.B.; Chu, C.T.; Griffith, L.; Wells, A. Human mesenchymal stem cells/multipotent stromal cells consume accumulated autophagosomes early in differentiation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 140.

- Farrell, M.; Shin, J.; Smith, L.; Mauck, R. Functional consequences of glucose and oxygen deprivation on engineered mesenchymal stem cell-based cartilage constructs. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 134–142.

- Kulkarni, G.V.; A McCulloch, C. Serum deprivation induces apoptotic cell death in a subset of Balb/c 3T3 fibroblasts. J. Cell Sci. 1994, 107 Pt 5, 1169–1179.

- Wan, P.X.; Wang, B.W.; Wang, Z.C. Importance of the stem cell microenvironment for ophthalmological cell-based therapy. World J. Stem Cells 2015, 7, 448–460.

- Wang, H.; Zhong, Q.; Yang, T.; Qi, Y.; Fu, M.; Yang, X.; Qiao, L.; Ling, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y. Comparative characterization of SHED and DPSCs during extended cultivation in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 6551–6559.

- Yao, Y.; Fu, K.Y. Serum-deprivation leads to activation-like changes in primary microglia and BV-2 cells but not astrocytes. Biomed. Rep. 2020, 13, 51.

- Periasamy, R.; Elshaer, S.L.; Gangaraju, R. CD140b (PDGFRbeta) signaling in adipose-derived stem cells mediates angiogenic behavior of retinal endothelial cells. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2019, 5, 1–9.

- Luo, J.; Martinez, J.; Yin, X.; Sanchez, A.; Tripathy, D.; Grammas, P. Hypoxia induces angiogenic factors in brain microvascular endothelial cells. Microvasc. Res. 2012, 83, 138–145.

- Dávila, D.; Connolly, N.M.C.; Bonner, H.; Weisová, P.; Düssmann, H.; Concannon, C.G.; Huber, H.J.; Prehn, J.H.M. Two-step activation of FOXO3 by AMPK generates a coherent feed-forward loop determining excitotoxic cell fate. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 1677–1688.

- Kim, J.; Yang, G.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Ha, J. AMPK activators: mechanisms of action and physiological activities. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e224.

- Mihaylova, M.M.; Shaw, R.J. The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 1016–1023.

- Mirouse, V.; Billaud, M. The LKB1/AMPK polarity pathway. FEBS Lett. 2010, 585, 981–985.