Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Noha Attia Hussien | + 4652 word(s) | 4652 | 2022-01-07 04:42:30 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 4652 | 2022-01-09 09:40:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Attia Hussien, N. Cell-Based Therapy for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17883 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Attia Hussien N. Cell-Based Therapy for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17883. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Attia Hussien, Noha. "Cell-Based Therapy for the Treatment of Glioblastoma" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17883 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Attia Hussien, N. (2022, January 07). Cell-Based Therapy for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17883

Attia Hussien, Noha. "Cell-Based Therapy for the Treatment of Glioblastoma." Encyclopedia. Web. 07 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Glioblastoma (GB), an aggressive primary tumor of the central nervous system, represents about 60% of all adult primary brain tumors. It is notorious for its extremely low (~5%) 5-year survival rate which signals the unsatisfactory results of the standard protocol for GB therapy. This issue has become, over time, the impetus for bringing novel therapeutics to the surface and challenging them so they can be improved. The cell-based approach in treating GB found its way to clinical trials thanks to a marvelous number of preclinical studies that probed various types of cells aiming to combat GB and increase the survival rate.

glioma

stem cell

CAR-T cell

immune cell therapy

cell therapy

cancer

1. Cell Therapy for Glioblastoma

1.1. Immune Cell Therapy

A large body of literature provides evidence for the promising potential of immunotherapy in the treatment of GB. Being notorious for its extensive local invasion into deeper areas of the CNS, GB is always difficult to resect. Due to this obstacle, immunotherapy is taking the forefront as a promising treatment option for those diagnosed with GB. Various immune cell types are reported to specifically attack the tumor cells using myriad mechanisms of recognition and destruction. Many of those cells will be discussed separately below.

1.1.1. Lymphocytes/CAR-T

When considering immune cells, it is always important to discuss the role of T and B lymphocytes. Both cell types work together to formulate the immune responses our bodies have towards invasive antigens and substances. They can easily cross the BBB under certain physiological and pathological conditions [1], and they perform well when combating tumors. Nair and colleagues induced certain T cells in vitro to become CMV pp65-specific, thus acquiring the capability to recognize and kill tumor cells at an increased rate [2]. T cells can elicit a powerful mechanism to eliminate internal and external pathogens. Therefore, they are being used therapeutically to manage different malignancies with promising outcomes [1].

In a recent study, Lee-Chang et al. [3] developed a vaccine utilizing B cells activated with CD40 agonism and IFNy stimulation. This vaccine aims to travel to secondary lymphoid organs and increase antigen cross-presentation. As a result, this vaccine promotes the survival and functionality of CD8+ T cells [3]. It was found that when this vaccine was combined with other treatments such as radiation and PD-L1 blockade, this combination was able to elicit immunological memory that prevented the growth of new tumor cells.

The chimeric antigen receptors (CAR-) T cells are a product of genetic engineering in an effort to achieve a long-term outcome in cases of malignancies such as GB. CAR-T cells are genetically programmed to attack tumor cells by recognizing the surface proteins expressed [4]. They are developed to target tumor-associated antigens (TAA), such as interleukin 13 receptor α 2 (IL13Rα2), epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular carcinoma A2 (EphA2) [5][6]. These artificial proteins are composed of an extracellular antigen-binding domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular T-Cell signaling domain like Cd3 ζ (with or without costimulatory components) [7]. Different generations of CAR-T cells have been studied with outstanding outcomes in redirecting the cytotoxic nature of T lymphocytes to become independent of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restrictions and without requiring antigen priming [8]. First generation CAR-T cells have an antigen recognition domain (scFv) and the activating signal CD3 ζ, a costimulatory molecule, can be added to form a second and third generation CAR with two costimulatory molecules [9]. Recently, Bielamowicz et al. Bielamowicz, Fousek [10] stated that GB cells overexpress different and targetable surface antigens, such as HER2, IL13Rα2, EphA2 and EGFRvIII which have been targeted using CAR-T cells with promising outcomes.

EGFRvIII is a variant of EGFR present in 31–64% of patients with GB that promote tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis in the tumor environment [11]. EFRON vIII CAR-T cells localized to intracerebral tumors reduce the expression of EGFRvIII in cancer cells [12]. Chen et al. [11] generated an EGFRvIII-targeting CAR (806-28Z CAR) using the epitope of 806 antibody, which is only fully exposed on EGFRvIII or activated EGFR, for in vitro and in vivo testing with an SQ xenograft established by injecting 1 × 107 GL261/EGFRvIII cells mixed with Matrigel (4:1) into the right limb of C57BL/6 mice. They reported dose-dependent cytotoxicity against mouse GL261/EGFRvIII cells, effective inhibition of tumor growth, effective lysis of mixed heterogenous GL261 cells accompanied with high concentrations of granzyme B which can be used as a predictive marker to determine the effectiveness of CAR-T cells as a therapeutic approach [11]. Likewise, Ravanpay et al. [13] used EFGR806-CAR through intracranial administration to treat xenograft GB mouse models. Placing the CAR-T cells near the target site lowered the risk of side effects outside the CNS and ensured consistent regression of orthotopic glioma.

HER2 antigen is over expressed in about 80% of GB cases and was incorporated in the design of a third generation anti-HER2 CAR (anti-HER2 scFv-CD28-CD137-CD3ζ) combined with a PD1 blockade and anti-HER2 scFv from the 4D5 antibody for CAR construction to avoid a decreased binding of CAR to antigen [9]. The costimulatory molecule, CD28, induced and increased production of IL-2, enhancing the clonal expansion and endurance of CAR T cells that, when combined with 4-1BB/CD137, were more efficient in INF-γ production and lysis of tumor cells [9]. TanCAR combined two antigen recognition domains for HER2 and IL13Rα2 previously proved to provide a “near-complete tumor elimination” in previous work by Hedge et al. [14]. Higher density of TanCAR-mediated HER2-IL13Rα2 heterodimers was observed on STED super resolution microscopes and confirmed by PLA in addition to increased IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion; all supporting the antitumor characteristic of this therapy [15]. Bielamowicz et al. [10] demonstrated that nearly 100% of tumor cells were killed, in vitro and in vivo, with UCAR-T, a trivalent transgene combining IL13Rα2 binding IL-13 mutein, HER2-specific single chain variable fragment 9scFv), FRP5, and Epha2-specific scFv 4H5 with CD28 as a costimulatory molecule and ζ-signaling domain of the T cell receptor (TCR). The UCAR T cell showed better signaling, increased engagement of a larger domain of GB cells and an almost entire activation and proliferation of the 3 CARs as demonstrated in surface staining [10].

In efforts to evidence long term immunity after therapy with CAR T cells, Pituch et al. [6] proposed the utilization of IL13Rα2-CARCD28ζ CAR-T cells and observed an increased number of CD8α+DC cells known to efficiently cross-present both cell-bound and soluble antigens in the MHC class I, therefore inducing a CD8+ T cell response. Krenciute et al. [5] designed the IL13Rα2-CAR.IL15T cell by modifying T cells with a retroviral vector that encoded an IL13Rα2-specific scFv with CD28.ζ endodomain and a retroviral vector that encoded inducible caspase-9, NGFR with a shortened cytoplasmic domain and IL15 separated by 2A sequence demonstrating that the action of IL15 in IL13Rα2-CAR T cells enhanced their effector functions. Although IL15 did not show any significant improvement in the proliferation of IL13Rα2-CAR T cells or cytokine production after the first antigen-specific stimulation, it showed significant proliferation after the third stimulation [5]. In light of the fact that steroids (e.g., dexamethasone) form part of the standard protocol of treatment for patients with different malignancies for alleviation of symptoms, it was demonstrated that the antitumor response and presence of intracranial IL13BBζ in T cell-treated mice were not significantly impaired after dexamethasone was given, when compared to the control group, by Brown, Aguilar [16].

Another molecule believed to be effective if used with CAR T cells is B7-H3, a type I transmembrane protein encoded by chromosome 15, which has costimulatory and co-inhibitory functions on T cell subsets [17]. B7-H3.CAR with CD28 costimulation showed a faster antitumor effect in comparison with 4-1BB co-stimulation with no markable difference in antiproliferative activity in general [18]. Although both costimulations showed cross-reactivity to murine B7-H3 without toxicity when infused systematically, and antitumor activity, using in vitro and xenograft GB murine models, allowed the elimination of both differentiated tumor cells and cancer stem cells (CSCs). The low expression of B7-H3 in one third of GB cells demonstrated effective killing by B7-H3.CAR-T cells [18].

In an effort to understand the dynamics of the cytotoxic effects of T-cells in GB to establish better delivery of therapies, Murty, Haile [19] used intravital microscopy to evidence the use of CAR-T cells along with focal radiation, achieving complete tumor regression in vivo. In another study, the IV administration of IL13BBζ was shown to be ineffective, possibly due to deficient cell trafficking to the intracranial tumors, pointing out intracranial therapy with CAR-T cells as a better option for long-term survival [16].

Nevertheless, tumor recurrence is the top burden in the development of effective therapies for GB. Patients treated with IL13Rα2-targeted CAR-T cells showed recurrence with loss and/reduced expression of IL13Rα2 reducing the efficacy of the therapy and making it even more difficult after treatments [8]. Moreover, to achieve complete eradication of GB, there are some barriers yet to concur, such as the suboptimal penetration of CAR-T cells within the tumor stroma, the poor effector function of T cells which inhibits a continuous antigen-driven stimulation and the minimal antigen specificity as a consequence of the heterogeneity of the GB tumor that could cause off-site toxicities [19]. There is also a need for further investigation on how to enhance the endurance of CAR-T cells within the tumor environment to eradicate large tumors or even better early detection and eradication of tumor recurrence [18].

1.1.2. Natural Killer (NK) Cells

The use of NK cells is the most preferred immunotherapy approach discussed in the literature regarding the GB treatment. The NK cells can be used for the targeted killing of glioma cells. Further, they can be used in combination with other immunotherapies including inhibitors for immune checkpoints, drugs targeting immune-related genes, or specific antibodies that block the action of proteins protecting NK cells from immunosuppression [20][21][22][23]. Although a large body of evidence suggests a positive effect of NK cells as immunotherapy in GB treatment, the major hurdle is to mitigate the suppression of the cytotoxic effects of NK cells.

A study by Lee et al. reported the potential use of NK cells in the inhibition of systemic metastasis of GB cells in the mice model. This was attributed to the cytotoxic effects of NK cells against GB cells. Therefore, adequate supplementation of NK cells to the brain can be considered as a promising immunotherapy to treat GB [21]. The killer Ig-like receptor (KIR) genotypes in NK cells are correlated with various tumor types. The presence of KIR2DS2 immuno-genotype NK cells was shown to be associated with more potent cytotoxic activity against GB [20].

Another approach discussed in the literature includes the adoptive transfer of CAR-modified immune cells for the treatment of GB. A Han et al. study elucidated the use of CAR-engineered NK cells in the treatment of GB via targeting wild-type EGFR as well as mutant form EGFRvIII. These EGFR-CAR engineered NK cells demonstrated increased tumor cell lysis capacity, stimulated production of IFN-γ, and further suppressed the tumor growth and subsequently improved survival outcome for a long period [24]. The observations of another study published in 2016 were concordant with the above-mentioned evidence [25].

A study by Tanaka et al. reported another approach using a combination of ex vivo-expanded highly purified natural killer cells (genuine induced NK cells (GiNK)) and the chemotherapeutic agent temozolomide for the treatment of GB. This therapy has been shown to help to stimulate anticancer effects including the stimulation of tumor cell death in human GB cells in vitro [26]. In addition, another study demonstrated that the use of the pretreatment approach of GB with another anticancer agent, bortezomib, helped to stimulate the cytotoxicity of NK cells by inducing TRAIL-R2 expression and enhanced GB lysis due to increased IFN-γ release [27]. Recent research involving the treatment of NK cells with IL-2/HSP70 stimulated BBB crossing and the subsequent antitumor effects of NK cells and resulted in a substantial tumor growth inhibition and prolonged survival in an in vivo study [28].

In a study published in 2005, tumor-derived RNA transfected dendritic cells (DCs) were shown to increase the cytotoxic ability of NK-like T cells by recognizing and killing the tumor cells using adaptive as well as innate immune systems, thereby enhancing antitumor effects against the tumor from which RNA was originated [29].

Furthermore, NK cells were used as a vehicle for oncolytic enterovirus delivery in several recently published studies [30][31]. Recently published evidence by Shaim et al. reported an innovative mechanism of NK cell immune evasion by GB stem cells by targeting the integrin-TGF-β axis, leading to its inhibition and consequently improving the antitumor effects of NK cells against GB [32].

1.1.3. Dendritic Cells (DCs)

Many different experiments have utilized dendritic cells (DCs) in different ways to aid in therapies. In a study conducted in 2018, it was found that if DCs were used to mediate the delivery of nano-DOX, it would result in the stimulation of GB cell immunogenicity and this method would result in an antitumor immune response in GB [33]. Additionally, there have also been vaccines created that have improved the survival rates and tumor regression rates by elevating the antitumor immune function. One of these vaccines, named STEDNVANT, was established in 2018 and it was found to upregulate PD-1 and its ligand on PD-L1 effector T cells, DCs, and GB tissues [34]. This resulted in an increase of regulatory T cells in the brain tissue and lymph nodes. When this vaccine was combined with the antibodies of anti-PDL1 it was proven to show a greater survival rate and a decrease in the T-regulatory cell population in the brain [34].

1.1.4. Monocytes/Macrophages

Another immune cell subtype, monocytes, was also studied and proven to be beneficial against gliomas. In 2017, Wang et al. found that monocytes loaded with nano-doxorubicin were able to successfully cross an artificial endothelial barrier and were able to release drugs in GB spheroids once they got inside [35]. This drug release method was proven to improve the effectiveness of the drugs they were meant to deliver to the mice in this experiment and improved their tumors [35]. Utilizing a similar method, another study was able to deliver monocytes that were loaded with conjugated polymer nanoparticles into GB cells and that allowed for the expansion and improvement of photodynamic therapy for GB [36]. Additionally, another experiment by Gattas and colleagues, [37] used primary monocytes that were cultured in the presence of U87MG-conditioned media, and co-cultured with GB spheroids. They found that monocytes differentiated and acquired clear M2 phenotypes, while also inducing alterations in the cell cultures. The fact that these monocytes upregulated CD206, CD163 and MERTK surface markers on the CD11b and CD14 populations made them strong inducers of anti-inflammatory macrophages [37]. These three studies can be referenced together to show the range of ways that immune cells can be used to provide care to those with life-devastating tumors.

1.1.5. Neutrophils

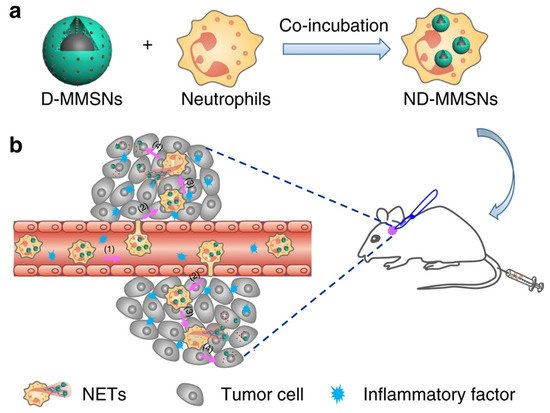

Neutrophils are considered one of the promising immune system cells that are useful in the intracranial treatment of GB in terms of an effective drug delivery system to the target area by enhanced penetration through the BBB. A recently developed novel approach for GB includes an ultrasound augmented chemo/immunotherapy using a neutrophil-delivered nanosensitizer [38][39][40]. In a Li Y, et al. study, authors introduced a novel design wherein a hollow titania (TiO2)-covered persistent luminescent nanosensitizer was used for optical imaging-guided, ultrasound-augmented chemo/immunotherapy against GB. Specifically, neutrophils were used as drug delivery vehicles wherein they were loaded with hollow titania (ZGO@TiO2@ALP-NEs) which can cross BBB and reach target GB cells effectively. The postactivation of this system using ultrasound radiation results in ROS generation from ZGO@TiO2@ALP further causing liposome destruction and drug release at the GB sites. This ultimately leads to local inflammation thereby enhancing the migration of more drug-loaded NEs into the tumor sites for augmented and sustained therapy. This treatment approach showed improved survival in a mice model with GB which provides the benefit of immuno-surveillance of recurrent tumors for a long period [38]. In addition, other studies also provide evidence in support of neutrophils as a promising drug delivery system in GB therapy, as seen in Figure 1 [40].

Figure 1. Fabrication and targeted-therapeutic schematics of ND-MMSNs to achieve residual tumor theranostics. (a) Schematic illustration of the preparation of ND-MMSNs. (b) Schematic shows that inflammation-activatable ND-MMSNs target inflamed glioma sites and phagocytized D-MMSNs would be released to achieve residual tumor theranostics [40] (CC by 4.0).

Despite the great promise immunotherapy has in cases of GB, the disease is quite notorious for its high recurrence rate [41]. The recurring tumor cells depict high heterogeneity and serious radiotherapy/chemotherapy-induced genotoxicity. Moreover, most of the time, those tumors often engage in antigen escape after immunotherapy, thus it is not feasible to apply immunotherapy on recurring GB [42]. For instance, CAR-T cell and vaccination therapies did not achieve satisfactory results in clinical trials on cases with recurrent GB [43].

1.2. Stem Cell Therapy

The potential utility of stem cells as sources for cell-based therapy has been viewed as the next generation treatment for GB. The therapeutic effect of various types of stem cells were tested on GB in preclinical and clinical settings. Stem cells are capable of self-replication, differentiation, tumor tropism, and many other features rendering them appealing therapeutic candidates. In addition to their ability to regenerate CNS cells after tissue injury following surgery and/or chemotherapy, they have been believed to exhibit direct/indirect antitumor effects. The preclinical evidence for such therapeutic effects of stem cells in GB is discussed next.

1.2.1. Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)

In 1966, the existence of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in bone marrow was reported by Friedenstein et al. [44]. The term “mesenchymal stem cells” was proposed by Caplan, in 1991 [45]. This term reflected their ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes. Later, MSCs were found to be present in many other tissues, like adipose tissue, umbilical cord, menstrual blood, dental pulp, etc. [46][47][48][49].

Overtime, MSCs were recognized to have the inherent ability of self-renewal. However, there was no definite marker for MSCs so far [50][51][52][53]. Therefore, the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established the minimal criteria for MSCs that were defined based on their biological features. Firstly, MSCs must have plastic adherent growth. Secondly, MSCs must have positively expressed CD73, CD90, and CD105 surface antigens and have negative expression of CD14 or CD11b, CD 19 or CD 79α, CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR surface molecules. Thirdly, MSCs must show differentiation ability towards osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro [54][55].

Of note, the MSCs in human GB can demonstrate ISCT criteria [56]. However, they can express slightly different cell surface markers. These are desmin, vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and nerval/glial antigen [57][58]. This shows that cell surface expression is not limited to ISCT criteria. MSCs taken from different sources have also been shown to differentiate into multiple cell lines under specific in vivo and in vitro conditions [58]. The biological features of MSCs are complex and manifold in their regulation. The main reason for the slight differences in the biological characteristics of MSCs is due to the microenvironment conditions in the different sources. miRNAs are relatively newer mechanisms that can regulate the biological features of MSCs. The microenvironment and signaling pathway interactions of MSCs can be better understood in their role in modulating the biological features of MSCs in the treatment of GB [59].

1.2.2. Neural Stem Cells (NSCs)

Neural stem cells (NSCs) have two main characteristics: the capacity of self-renewal and their potential to differentiate into neural progenitor cells (limited potential, limited self-renewal) including the cells of the neuronal lineage, such as neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [60]. Progenitor cells are typically found in the brain and spinal cord and easily differentiate into neural or glial progenitor cells [60]. Alongside the developing brain, the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricle has been identified as a source of adult animal NSC generation and is also subject to biopsy and cell culture [61].

Due to the link between NSCs and GB, NSCs are presently being explored as optimal models to further explore the knowledge of GB. Additionally, the switch seen between neurogenic to gliogenic is characterized by a burst of oncogenic alterations, which has further indicated that transcription factor AP-1—typically seen in basal gene expression—would ultimately inhibit gliomagenesis if it were transiently inhibited [62]. Ultimately, the use of NSCs to explore the progression of glioma tumorigenesis has uncovered imperative information that would be beneficial to the treatment of GB. Additionally, the NSCs have a unique GB tumor-homing property that would make them beneficial for targeted therapies, such as delivering apoptosis-inducing ligands that can be targeted to the tumorigenic cells and work to induce apoptosis on the tumor cells [63][64].

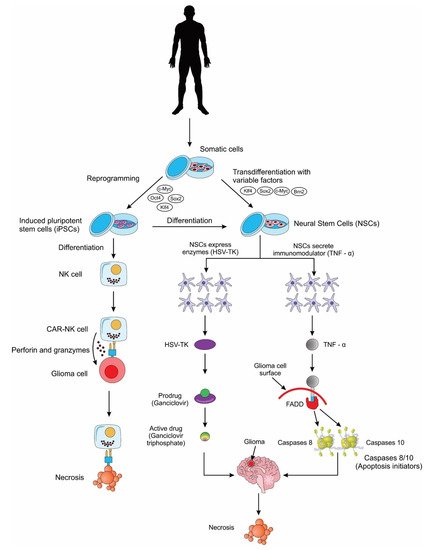

Induced neural stem cells (iNSCs), cells that undergo transdifferentiation from the patients’ skin, are used as drug carriers with an innate tropism to neural cells including GB [65]. These cell derivatives can be genetically engineered to express cytotoxic proteins, which aid in cancer destruction as the cells will naturally migrate towards the cancer-invading area [65]. The iNSCs could carry therapeutic agents such as TNF α, and thymidine kinase [65]. Of these agents, the TNF α is a TNF α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) that can diffuse to nearby cells [65]. TRAIL, once in the diffused cells, can induce caspase-mediated apoptosis via engagement of the death receptor with negligible off-target toxicities [65]. The other agent, thymidine kinase TK, is an agent that remains inactive until the prodrug valganciclovir is co-administered and is hydrolyzed to ganciclovir [65]. The TK agent of the iNSCs will phosphorylate the circulating ganciclovir into cytotoxic ganciclovir triphosphate and accentuate the method of action of the drug, which is the inhibition of DNA polymerase—killing iNSCs as well as tumor cells [65].

Along the lines of the TK agent, there is also the notion of the bystander effect from lentiviral vectors followed with doxycycline or ganciclovir [64]. The bystander effect is the idea that the NSCs would only act as a bystander, only needed to deliver the vector [66]. The majority of the action is done by the vector that is delivered by the bystander, in this case, the bystander is the NSCs, and the vector is the agent targeting the cancerous cells. The results of the study showed that the lentiviral vector was compatible with human clinical use, though the timing of ganciclovir administration should be taken into consideration—weaker effects are seen when ganciclovir is administered a week following the transfer of the mesenchymal cells and vector [64].

Presently, the examination of lymphocyte-directed treatment is under examination as well as the use of bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) on the efficacy of recruiting T cells and the production of proinflammatory cytokines interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) [67]. Bispecific T-cell engagers consist of two single-chain variable fragments connected by a flexible linker [67]. One of the singe-chain variable fragments is directed to a thymidine-adenosine-adenosine and the other to CD3 epsilon that is expressed on T cells [67]. Bispecific T-cell engagers have a specificity to tumor therapeutic potential when pairing with a recombinant molecule [67]. Studies have shown that neural stem cells that have been modified to produce BiTEs are capable of recruiting T cells as well as the proinflammatory cytokines interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) [67]. Additionally, it is also seen that there is the effective killing of GB cancer cells with the NSCs modified with BiTEs, specifically the promotion of T-cell killing of IL13Rα2+ tumor cells by engaging the tumor cell antigen with CD3 epsilon T cells that effectively target them [67]. Overall, NSCs can also be applied as a means for an innate reaction.

As the use of NSCs for the delivery of therapeutics has become a highly explored subject, the efficacy of drug usage has been explored with a three-dimensional culture system to confirm the efficacy as well [68]. Through a three-dimensional culture system, NSCs were analyzed based on tumor location for the effect of their migration [68]. It was seen that when NSCs were implanted 2mm lateral from the tumor foci, they were found to colocalize with multiple tumors and preferred to migrate to the tumor foci that were near the site of implantation [68].

It is additionally observed that NSCs can speed up the tumor formation process [69]. Thus, if a treated NSC that is to be used as a vector proves to be defective, it is possible for the NSC that is introduced to further contribute and move the disease process along [69]. It is postulated that NSCs are self-limited and the process in which the cells are used in treatment additionally includes a termination process that also limits the cells from progressing into a cell line [64].

1.2.3. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

Since Shinya Yamanaka created induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in 2006, the field of stem cell research has been revolutionized [70][71][72]. With the somatic cell reprogramming technology, it is now possible to reprogram virtually any somatic cells to a pluripotent embryonic stem cell-like state by delivery into the somatic cells of a mixture of reprogramming transcription factors [72]. Like embryonic stem cells (ESCs), iPSCs can proliferate infinitely in culture and will differentiate into the three embryonic germ cell layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), thus can develop into all cells of an adult organism, including neural stem cells (NSCs) [72]. Since ESCs are derived from pre-implantation embryos, their embryonic origin raises strong ethical concerns relating to embryo destruction, thus hampering their clinical application. iPSCs avoid these ethical issues thus opening the way for the progression of pluripotent stem cell research clinically [72].

Namba and colleagues, in 2014, demonstrated that both iPSCs and iPSC-NSCs had a similar potent tumor tropism following transplantation, thus showing that iPSCs and their derivatives can be useful tools as vehicles of transport in stem cell-based gene therapy for the treatment of GB [73]. In two separate preclinical studies, Bago and colleagues use the process of transdifferentiation (TD) to generate iNSCs for the treatment of glioma [74][75]. TD involves the direct reprogramming of somatic cells into a lineage-specific cell (in this case NSCs), bypassing the dedifferentiation into a pluripotent stem cell. The resulting mouse and human iNSCs were engineered to produce a transmembrane protein called tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL). TRAIL can recruit Fas-associated proteins with death domain (FADD), which in turn bind to apoptotic caspases 8/10, thus inducing apoptosis and cell death in malignant cells [76][77][78][79][80][81]. The efficacy of this cytotoxic factor-based therapy study was demonstrated by the decrease in tumor size and the improvement in survival rates of the mice glioma model compared with controls [74][75]. In the second preclinical study, Bago and team tested the widely popular suicide-protein-based therapy method along with the cytotoxic-factor based therapy [75]. The suicide-protein-based therapy, or the enzyme/prodrug strategy involves a gene encoding an enzyme (suicide protein) into the stem cell. Once injected to the tumor site, the enzyme converts the non-toxic pro-drug into a toxic pro-drug which helps to regress the tumor cells. The most used combination is the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) with ganciclovir (GCV). The HSV-TK converts GCV into GCV monophosphate, and this is further phosphorylated to GCV triphosphate. GCV triphosphate is a toxic antimetabolite that inhibits DNA polymerase thus leading to tumor cell death [82]. The HSV-TK/GCV suicide-gene system was further demonstrated recently using human iPSC-derived NSCs and it showed considerable therapeutic potential for the treatment of GB [64]. Interestingly, in another study by Bhere et al. iPSC-derived NSCs were engineered to secrete both TRAIL and HSV-TK and a profound antitumor efficacy was demonstrated [83] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A schematic showing the different applications of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cells (iPSC-NSCs) for the treatment of glioblastoma cells. NK cell: natural killer cell; CAR: chimeric antigen receptor; HSV-TK: herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha; FADD: Fas-associated proteins with death domain.

NK cells are specialized killer cells of the innate immune system, with the natural ability to eliminate abnormal (tumor) cells without prior sensitization (unlike T-cells that require prior sensitization). Scientists have genetically modified human NK cells with CARs to further weaponize them for the treatment of gliomas. A few preclinical studies have now successfully demonstrated the use of iPSC-derived NK cells for the treatment of GB, thus providing proof-of-concept for the use of these cells in future clinical trials [84][85] (Figure 2).

References

- Kim, G.B.; Aragon-Sanabria, V.; Randolph, L.; Jiang, H.; Reynolds, J.A.; Webb, B.S.; Madhankumar, A.; Lian, X.; Connor, J.R.; Yang, J.; et al. High-affinity mutant Interleukin-13 targeted CAR T cells enhance delivery of clickable biodegradable fluorescent nanoparticles to glioblastoma. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 624–635.

- Nair, S.K.; De Leon, G.; Boczkowski, D.; Schmittling, R.; Xie, W.; Staats, J.; Liu, R.; Johnson, L.A.; Weinhold, K.; Archer, G.E.; et al. Recognition and killing of autologous, primary glioblastoma tumor cells by human cytomegalovirus pp65-specific cytotoxic T cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2684–2694.

- Lee-Chang, C.; Miska, J.; Hou, D.; Rashidi, A.; Zhang, P.; Burga, R.A.; Jusué-Torres, I.; Xiao, T.; Arrieta, V.A.; Zhang, D.Y.; et al. Activation of 4-1BBL+B cells with CD40 agonism and IFNγ elicits potent immunity against glioblastoma. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 218, e20200913.

- Wang, D.; Aguilar, B.; Starr, R.; Alizadeh, D.; Brito, A.; Sarkissian, A.; Ostberg, J.R.; Forman, S.J.; Brown, C.E. Glioblastoma-targeted CD4+CAR T cells mediate superior antitumor activity. JCI Insight 2018, 3, 99048.

- Krenciute, G.; Prinzing, B.L.; Yi, Z.; Wu, M.-F.; Liu, H.; Dotti, G.; Balyasnikova, I.V.; Gottschalk, S. Transgenic expression of IL15 improves antiglioma activity of IL13Rα2-CAR T cells but results in antigen loss variants. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 571–581.

- Pituch, K.C.; Miska, J.; Krenciute, G.; Panek, W.K.; DeFelice, G.; Rodriguez-Cruz, T.; Wu, M.; Han, Y.; Lesniak, M.S.; Gottschalk, S.; et al. Adoptive transfer of IL13Rα2-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells creates a Pro-inflammatory environment in glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 986–995.

- Yang, D.; Sun, B.; Dai, H.; Li, W.; Shi, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, S.; Zhao, X. T cells expressing NKG2D chimeric antigen receptors efficiently eliminate glioblastoma and cancer stem cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 171.

- Wang, D.; Starr, R.; Chang, W.-C.; Aguilar, B.; Alizadeh, D.; Wright, S.L.; Yang, X.; Brito, A.; Sarkissian, A.; Ostberg, J.R.; et al. Chlorotoxin-directed CAR T cells for specific and effective targeting of glioblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, 2672.

- Shen, L.; Li, H.; Bin, S.; Li, P.; Chen, J.; Gu, H.; Yuan, W. The efficacy of third generation anti-HER2 chimeric antigen receptor T cells in combination with PD1 blockade against malignant glioblastoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 1549–1557.

- Bielamowicz, K.; Fousek, K.; Byrd, T.T.; Samaha, H.; Mukherjee, M.; Aware, N.; Wu, M.-F.; Orange, J.S.; Sumazin, P.; Man, T.-K.; et al. Trivalent CAR T cells overcome interpatient antigenic variability in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, 506–518.

- Chen, M.; Sun, R.; Shi, B.; Wang, Y.; Di, S.; Luo, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, H. Antitumor efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor T cells against EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastoma in C57BL/6 mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 113, 108734.

- Choi, B.D.; Yu, X.; Castano, A.P.; Darr, H.; Henderson, D.B.; Bouffard, A.A.; Larson, R.C.; Scarfò, I.; Bailey, S.R.; Gerhard, G.M.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 disruption of PD-1 enhances activity of universal EGFRvIII CAR T cells in a preclinical model of human glioblastoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 304.

- Ravanpay, A.C.; Gust, J.; Johnson, A.J.; Rolczynski, L.S.; Cecchini, M.; Chang, C.A.; Hoglund, V.J.; Mukherjee, R.; Vitanza, N.A.; Orentas, R.J.; et al. EGFR806-CAR T cells selectively target a tumor-restricted EGFR epitope in glioblastoma. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 7080–7095.

- Hegde, M.; Corder, A.; Chow, K.K.; Mukherjee, M.; Ashoori, A.; Kew, Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Baskin, D.S.; Merchant, F.; Brawley, V.S.; et al. Combinational targeting offsets antigen escape and enhances effector functions of adoptively transferred T cells in glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 2087–2101.

- Hegde, M.; Mukherjee, M.; Grada, Z.; Pignata, A.; Landi, D.; Navai, S.; Wakefield, A.; Fousek, K.; Bielamowicz, K.; Chow, K.K.; et al. Tandem CAR T cells targeting HER2 and IL13Rα2 mitigate tumor antigen escape. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3036–3052.

- Brown, C.E.; Aguilar, B.; Starr, R.; Yang, X.; Chang, W.-C.; Weng, L.; Chang, B.; Sarkissian, A.; Brito, A.; Sanchez, J.F.; et al. Optimization of IL13Rα2-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells for improved anti-tumor efficacy against glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 31–44.

- Tang, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Guo, G.; Tong, A.; et al. B7-H3 as a novel CAR-T therapeutic target for glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2019, 14, 279–287.

- Nehama, D.; Di Ianni, N.; Musio, S.; Du, H.; Patanè, M.; Pollo, B.; Finocchiaro, G.; Park, J.H.; Dunn, D.E.; Edwards, D.; et al. B7-H3-redirected chimeric antigen receptor T cells target glioblastoma and neurospheres. EBioMedicine 2019, 47, 33–43.

- Murty, S.; Haile, S.T.; Beinat, C.; Aalipour, A.; Alam, I.S.; Murty, T.; Shaffer, T.M.; Patel, C.B.; Graves, E.E.; Mackall, C.L.; et al. Intravital imaging reveals synergistic effect of CAR T-cells and radiation therapy in a preclinical immunocompetent glioblastoma model. OncoImmunology 2020, 9, 1757360.

- Navarro, A.G.; Kmiecik, J.; Leiss, L.; Zelkowski, M.; Engelsen, A.; Bruserud, Ø.; Zimmer, J.; Enger, P.Ø.; Chekenya, M. NK Cells with KIR2DS2 immunogenotype have a functional activation advantage to efficiently kill glioblastoma and prolong animal survival. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 6192–6206.

- Lee, S.J.; Kang, W.Y.; Yoon, Y.; Jin, J.Y.; Song, H.J.; Her, J.H.; Kang, S.M.; Hwang, Y.K.; Kang, K.J.; Joo, K.M.; et al. Natural killer (NK) cells inhibit systemic metastasis of glioblastoma cells and have therapeutic effects against glioblastomas in the brain. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 1–13.

- Zhang, Q.; Bi, J.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Peng, H.; Wei, H.; et al. Blockade of the checkpoint receptor TIGIT prevents NK cell exhaustion and elicits potent anti-tumor immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 723–732.

- Hung, A.L.; Maxwell, R.; Theodros, D.; Belcaid, Z.; Mathios, D.; Luksik, A.S.; Kim, E.; Wu, A.; Xia, Y.; Garzon-Muvdi, T.; et al. TIGIT and PD-1 dual checkpoint blockade enhances antitumor immunity and survival in GBM. OncoImmunology 2018, 7, e1466769.

- Han, J.; Chu, J.; Chan, W.K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cohen, J.; Victor, A.; Meisen, W.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Grandi, P.; et al. CAR-engineered NK cells targeting wild-type EGFR and EGFRvIII enhance killing of glioblastoma and patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11483.

- Genßler, S.; Burger, M.C.; Zhang, C.; Oelsner, S.; Mildenberger, I.; Wagner, M.; Steinbach, J.P.; Wels, W.S. Dual targeting of glioblastoma with chimeric antigen receptor-engineered natural killer cells overcomes heterogeneity of target antigen expression and enhances antitumor activity and survival. OncoImmunology 2016, 5, e1119354.

- Tanaka, Y.; Nakazawa, T.; Nakamura, M.; Nishimura, F.; Matsuda, R.; Omoto, K.; Shida, Y.; Murakami, T.; Nakagawa, I.; Motoyama, Y.; et al. Ex vivo-expanded highly purified natural killer cells in combination with temozolomide induce antitumor effects in human glioblastoma cells in vitro. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212455.

- Navarro, A.G.; Espedal, H.; Joseph, J.V.; Trachsel-Moncho, L.; Bahador, M.; Gjertsen, B.T.; Kristoffersen, E.K.; Simonsen, A.; Miletic, H.; Enger, P.Ø.; et al. Pretreatment of glioblastoma with Bortezomib potentiates natural killer cell cytotoxicity through TRAIL/DR5 mediated apoptosis and prolongs animal survival. Cancers 2019, 11, 996.

- Sharifzad, F.; Mardpour, S.; Mardpour, S.; Fakharian, E.; Taghikhani, A.; Sharifzad, A.; Kiani, S.; Heydarian, Y.; Los, M.J.; Ebrahimi, M.; et al. HSP70/IL-2 treated NK cells effectively cross the blood brain barrier and target tumor cells in a rat model of induced glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2263.

- Vichchatorn, P.; Wongkajornsilp, A.; Petvises, S.; Tangpradabkul, S.; Pakakasama, S.; Hongeng, S. Dendritic cells pulsed with total tumor RNA for activation NK-like T cells against glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neuro-Oncology 2005, 75, 111–118.

- Podshivalova, E.S.; Semkina, A.S.; Kravchenko, D.S.; Frolova, E.I.; Chumakov, S.P. Efficient delivery of oncolytic enterovirus by carrier cell line NK-92. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2021, 21, 110–118.

- Rich, J.N. Cancer stem cells in radiation resistance. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8980–8984.

- Shaim, H.; Shanley, M.; Basar, R.; Daher, M.; Gumin, J.; Zamler, D.B.; Uprety, N.; Wang, F.; Huang, Y.; Gabrusiewicz, K.; et al. Targeting the αv integrin/TGF-β axis improves natural killer cell function against glioblastoma stem cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131.

- Li, T.-F.; Li, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Yue, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, S.-J.; Liu, X.; Wen, Y.; Han, M.; et al. Dendritic cell-mediated delivery of doxorubicin-polyglycerol-nanodiamond composites elicits enhanced anti-cancer immune response in glioblastoma. Biomaterials 2018, 181, 35–52.

- Zhu, S.; Lv, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Zang, G.; Yang, N.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.-J.; et al. An effective dendritic cell-based vaccine containing glioma stem-like cell lysate and CpG adjuvant for an orthotopic mouse model of glioma. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 144, 2867–2879.

- Wang, C.; Li, K.; Li, T.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Y.; Liu, X.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Han, M.; et al. Monocyte-mediated chemotherapy drug delivery in glioblastoma. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 157–178.

- Ibarra, L.; Beaugé, L.; Arias-Ramos, N.; Rivarola, V.; Chesta, C.; López-Larrubia, P.; Palacios, R. Trojan horse monocyte-mediated delivery of conjugated polymer nanoparticles for improved photodynamic therapy of glioblastoma. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 1687–1707.

- Gattas, M.; Estecho, I.; Huvelle, M.L.; Errasti, A.; Silva, E.C.; Simian, M. A heterotypic tridimensional model to study the interaction of macrophages and glioblastoma in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5105.

- Li, Y.; Teng, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Yan, X.; Li, J. Neutrophil delivered hollow titania covered persistent luminescent nanosensitizer for ultrosound augmented chemo/immuno glioblastoma therapy. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2004381.

- Xue, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xue, L.; Shen, S.; Wen, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L.; Kong, L.; Sun, H.; et al. Neutrophil-mediated anticancer drug delivery for suppression of postoperative malignant glioma recurrence. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 692–700.

- Wu, M.; Zhang, H.; Tie, C.; Yan, C.; Deng, Z.; Wan, Q.; Liu, X.; Yan, F.; Zheng, H. MR imaging tracking of inflammation-activatable engineered neutrophils for targeted therapy of surgically treated glioma. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–13.

- Goenka, A.; Tiek, D.; Song, X.; Huang, T.; Hu, B.; Cheng, S.-Y. The many facets of therapy resistance and tumor recurrence in glioblastoma. Cells 2021, 10, 484.

- Lim, M.; Xia, Y.; Bettegowda, C.; Weller, M. Current state of immunotherapy for glioblastoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 422–442.

- Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Guo, G.; Yu, J. Immunotherapy for recurrent glioblastoma: Practical insights and challenging prospects. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1–15.

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Piatetzky, S., II; Petrakova, K.V. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1966, 16, 381–390.

- Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal stem cells. J. Orthop. Res. 1991, 9, 641–650.

- Rogers, I.; Casper, R.F. Umbilical cord blood stem cells. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obs. Gynaecol. 2004, 18, 893–908.

- Bussolati, B.; Bruno, S.; Grange, C.; Buttiglieri, S.; Deregibus, M.C.; Cantino, D.; Camussi, G. Isolation of renal progenitor cells from adult human kidney. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 545–555.

- Wang, X.-J.; Xiang, B.-Y.; Ding, Y.-H.; Chen, L.; Zou, H.; Mou, X.-Z.; Xiang, C. Human menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a cellular vehicle for malignant glioma gene therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 58309–58321.

- Wexler, S.A.; Donaldson, C.; Denning-Kendall, P.; Rice, C.; Bradley, B.; Hows, J.M. Adult bone marrow is a rich source of human mesenchymal ‘stem’ cells but umbilical cord and mobilized adult blood are not. Br. J. Haematol. 2003, 121, 368–374.

- Chen, L.-B.; Jiang, X.-B.; Yang, L. Differentiation of rat marrow mesenchymal stem cells into pancreatic islet beta-cells. World J. Gastroenterology 2004, 10, 3016–3020.

- Lee, K.-D.; Kuo, T.K.-C.; Whang-Peng, J.; Chung, Y.-F.; Lin, C.-T.; Chou, S.-H.; Chen, J.-R.; Chen, Y.-P.; Lee, O.K.-S. In vitro hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Hepatology 2004, 40, 1275–1284.

- Chang, D.-Y.; Jung, J.-H.; Kim, A.A.; Marasini, S.; Lee, Y.J.; Paek, S.H.; Kim, S.-S.; Suh-Kim, H. Combined effects of mesenchymal stem cells carrying cytosine deaminase gene with 5-fluorocytosine and temozolomide in orthotopic glioma model. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 1429–1441.

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147.

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.J.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E.M. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The international society for cellular therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317.

- Attia, N.; Mashal, M. Mesenchymal stem cells: The past present and future. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1312, 107–129.

- Mushahary, D.; Spittler, A.; Kasper, C.; Weber, V.; Charwat, V. Isolation, cultivation, and characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cytom. Part A 2018, 93, 19–31.

- Yi, D.; Xiang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Cen, Y.; Su, Q.; Zhang, F.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Fu, P. Human Glioblastoma-derived Mesenchymal stem cell to Pericytes transition and Angiogenic capacity in Glioblastoma microenvironment. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 46, 279–290.

- Zhang, Q.; Xiang, W.; Yi, D.-Y.; Xue, B.-Z.; Wen, W.-W.; Abdelmaksoud, A.; Xiong, N.-X.; Jiang, X.-B.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Fu, P. Current status and potential challenges of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for malignant gliomas. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 228.

- Attia, N.; Mashal, M.; Puras, G.; Pedraz, J. Mesenchymal stem cells as a gene delivery tool: Promise, problems, and prospects. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 843.

- Völker, J.; Engert, J.; Völker, C.; Bieniussa, L.; Schendzielorz, P.; Hagen, R.; Rak, K. Isolation and characterization of neural stem cells from the rat inferior colliculus. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 12.

- Zhang, G.-L.; Wang, C.-F.; Qian, C.; Ji, Y.-X.; Wang, Y.-Z. Role and mechanism of neural stem cells of the subventricular zone in glioblastoma. World J. Stem Cells 2021, 13, 877–893.

- Wang, X.; Zhou, R.; Xiong, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yan, X.; Wang, M.; Fan, L.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Sequential fate-switches in stem-like cells drive the tumorigenic trajectory from human neural stem cells to malignant glioma. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 684–702.

- Satterlee, A.B.; Dunn, D.; Lo, D.C.; Khagi, S.; Hingtgen, S. Tumoricidal stem cell therapy enables killing in novel hybrid models of heterogeneous glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2019, 21, 1552–1564.

- Tamura, R.; Miyoshi, H.; Morimoto, Y.; Oishi, Y.; Sampetrean, O.; Iwasawa, C.; Mine, Y.; Saya, H.; Yoshida, K.; Okano, H.; et al. Gene therapy using neural stem/progenitor cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells: Visualization of migration and bystander killing effect. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 352–366.

- Bomba, H.N.; Sheets, K.T.; Valdivia, A.; Khagi, S.; Ruterbories, L.; Mariani, C.L.; Borst, L.; Tokarz, D.A.; Hingtgen, S.D. Personalized-induced neural stem cell therapy: Generation, transplant, and safety in a large animal model. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2021, 6, 1.

- Li, S.; Tokuyama, T.; Yamamoto, J.; Koide, M.; Yokota, N.; Namba, H. Bystander effect-mediated gene therapy of gliomas using genetically engineered neural stem cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005, 12, 600–607.

- Pituch, K.C.; Zannikou, M.; Ilut, L.; Xiao, T.; Chastkofsky, M.; Sukhanova, M.; Bertolino, N.; Procissi, D.; Amidei, C.; Balyasnikova, I.V. Neural stem cells secreting bispecific T cell engager to induce selective antiglioma activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, 9.

- Carey-Ewend, A.G.; Hagler, S.B.; Bomba, H.N.; Goetz, M.J.; Bago, J.R.; Hingtgen, S.D. Developing bioinspired three-dimensional models of brain cancer to evaluate tumor-homing neural stem cell therapy. Tissue Eng. Part A 2020, 10, 1089.

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Meng, H.; Guan, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, G.; Wu, A.; Chen, L.; Yu, X. Neural stem cells promote glioblastoma formation in nude mice. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 21, 1551–1560.

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676.

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872.

- Omole, A.E.; Fakoya, A.O.J. Ten years of progress and promise of induced pluripotent stem cells: Historical origins, characteristics, mechanisms, limitations, and potential applications. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4370.

- Yamazoe, T.; Koizumi, S.; Yamasaki, T.; Amano, S.; Tokuyama, T.; Namba, H. Potent tumor tropism of induced pluripotent stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cells in the mouse intracerebral glioma model. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 46, 147–152.

- Bago, J.R.; Alfonso-Pecchio, A.; Okolie, O.; Dumitru, R.; Rinkenbaugh, A.; Baldwin, A.S.; Miller, C.; Magness, S.T.; Hingtgen, S.D. Therapeutically engineered induced neural stem cells are tumour-homing and inhibit progression of glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10593.

- Bagó, J.R.; Okolie, O.; Dumitru, R.; Ewend, M.G.; Parker, J.S.; Werff, R.V.; Underhill, T.M.; Schmid, R.S.; Miller, C.R.; Hingtgen, S.D. Tumor-homing cytotoxic human induced neural stem cells for cancer therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9.

- Pitti, R.M.; Marsters, S.A.; Ruppert, S.; Donahue, C.J.; Moore, A.; Ashkenazi, A. Induction of apoptosis by apo-2 ligand, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor Cytokine family. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 12687–12690.

- Oberst, A.; Pop, C.; Tremblay, A.G.; Blais, V.; Denault, J.-B.; Salvesen, G.S.; Green, D.R. Inducible dimerization and inducible cleavage reveal a requirement for both processes in caspase-8 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 16632–16642.

- Wang, J.; Chun, H.; Wong, W.; Spencer, D.M.; Lenardo, M.J. Caspase-10 is an initiator caspase in death receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 13884–13888.

- Hingtgen, S.; Ren, X.; Terwilliger, E.; Classon, M.; Weissleder, R.; Shah, K. Targeting multiple pathways in gliomas with stem cell and viral delivered S-TRAIL and Temozolomide. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 3575–3585.

- Kock, N.; Kasmieh, R.; Weissleder, R.; Shah, K. Tumor therapy mediated by lentiviral expression of shBcl-2 and S-TRAIL. Neoplasia 2007, 9, 435–442.

- Balyasnikova, I.V.; Ferguson, S.D.; Han, Y.; Liu, F.; Lesniak, M.S. Therapeutic effect of neural stem cells expressing TRAIL and bortezomib in mice with glioma xenografts. Cancer Lett. 2011, 310, 148–159.

- Calinescu, A.-A.; Kauss, M.C.; Sultan, Z.; Al-Holou, W.N.; O’Shea, S.K. Stem cells for the treatment of glioblastoma: A 20-year perspective. CNS Oncol. 2021, 10, CNS73.

- Bhere, D.; Khajuria, R.K.; Hendriks, W.T.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bagci-Onder, T.; Shah, K. Stem cells engineered during different stages of reprogramming reveal varying therapeutic efficacies. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 932–942.

- Miller, J.; Cichocki, F.; Ning, J.; Bjordahl, R.; Davis, Z.; Tuininga, K.; Wang, H.; Rogers, P.; He, M.; Chen, C. 155 iPSC-derived NK cells mediate robust anti-tumor activity against glioblastoma. J. ImmunoTher. Cancer 2020, 8, A93–A94.

- Yu, M.; Mansour, A.G.; Teng, K.Y.; Sun, G.; Shi, Y.; Caligiuri, M.A. Abstract 3313: iPSC-derived natural killer cells expressing EGFR-CAR against glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 3313.

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

735

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

09 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No