Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Md Al Saber | + 3130 word(s) | 3130 | 2021-12-27 09:32:42 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3130 | 2022-01-10 02:29:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Al Saber, M. Recent Advancements in Cancer Immunotherapy. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17876 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Al Saber M. Recent Advancements in Cancer Immunotherapy. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17876. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Al Saber, Md. "Recent Advancements in Cancer Immunotherapy" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17876 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Al Saber, M. (2022, January 07). Recent Advancements in Cancer Immunotherapy. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17876

Al Saber, Md. "Recent Advancements in Cancer Immunotherapy." Encyclopedia. Web. 07 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

This entry broadly focuses on recent immunotherapeutic techniques against cancer.

cancer immunotherapy

1. Background

The mechanisms involved in immune responses to cancer have been extensively studied for several decades, and considerable attention has been paid to harnessing the immune system’s therapeutic potential. Cancer immunotherapy has established itself as a promising new treatment option for a variety of cancer types. Various strategies including cancer vaccines, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), adoptive T-cell cancer therapy and CAR T-cell therapy have gained prominence through immunotherapy. However, the full potential of cancer immunotherapy remains to be accomplished.

2. The Current Immunotherapies That Are Used in Cancer Treatment

2.1. Adoptive Cell Therapy

Adoptive cell therapy is a form of treatment strategy that uses the cells of our immune system to eradicate the cancer of our body, mainly known as cellular immunotherapy. Cellular immunotherapy approaches directly involve the isolating of our own immune cells and simply increasing their numbers, whereas others require gene therapy for genetically engineering immune effector cells to enhance their anticancer capabilities [1]. Significant cancer immunotherapy approaches are illustrated here as tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL), engineered T-cell receptor (TCR), chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell and engineered natural killer cell (NK) therapy.

2.1.1. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL)

Naturally occurring T cells are powerful immune cells in our immune system that are engaged to fight against cancer cells, but the “killer-like T cells” are enabled to recognize and alleviate the cancer cells in a very particular way. To effectively kill cancer cells and activity for a durable period in order to sustain an effective antitumor response, killer T cells need to be harvested by ex vivo expansion from cancer patients to activate and expand the T cell numbers. Potentially, the huge amount of activated T cells are re-infused into patients and can directly encounter and destroy tumor cells [2]. Recent clinical reports proposed that tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) have been extensively used for patients who developed solid tumors, metastatic melanoma, ovarian cancer, renal cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and so on [3]. A clinical research study of the use of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) on cutaneous melanoma patients reported that TIL grade is a strong predictor of survival and sentinel lymph node (SLN) condition in patients with melanoma, and patients with a significant TIL impact have an increased survival rate [4]. Donastas et al., 2019 [5], noted that tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) showed potential anticancer activity on HLA-matched ovarian cancer cell lines, which was prior or post resistant to chemotherapy. In addition, many other research studies have demonstrated that tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) show strong anticancer activity on both the breast cancer and triple negative breast cancer research model [6][7].

2.1.2. Engineered T-Cell Receptor (TCR) Therapy

In some cases, T cells are unable to counter the advanced forms of cancer, so we requisition engineered T-cell receptors for action against solid tumors. This approach takes T cells from cancer patients and introduces the engineered novel receptors that enable them to target specific cancer antigens and tumor lysis, and eradicate the tumor cells. Here we declare that engineered T cells demonstrate their outstanding functions and their longevity in the tumor microenvironment [8]. Engineered T-cell receptors (TCRs) are composed of the α and β chains that are associated with δ, ε and γ chains, and the largest signaling regions of this receptor are known as the ζ chains. These novel T-cell receptors encounter the tumor antigens via the MHC-I/MHC-II and, with the advantage of engineered T cells, are able to identify suitable target antigens, overcome immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments, prevent antigen escape and reduce toxicities [9].

Adoptive immunotherapy with TCR-engineered T cells has been identified as a significant strategy for cancer treatment, with promising results from recent clinical trials [10]. This evolution was also demonstrated in clinical trials involving MART-1 TCR-engineered T cells in 2009 and 2014 [11][12]. Johnson et al. demonstrated that 19% of patients who were treated with T cells engineered with the gp100 TCR had an effective anticancer response [11]. Many other research studies have identified that patients with metastatic melanoma, multiple myeloma, colorectal carcinoma and synovial sarcoma possessed significant survival rates after treatment with TCR-engineered T cells [13][14][15].

2.1.3. Engineered Natural Killer (NK)-Cell Therapy

NK cell therapy involves augmenting the capability of NK cell antitumor responses via the introduction of antigen specificity by using genetic modification. Herein, CAR NK cells’ basic structural framework has similarity to CAR T cells, mainly CAR composed of extracellular, hinge, transmembrane as well as intracellular domains. The extracellular domain of CARs is ScFvs, which interact with the hinge domain and the transmembrane domains connected between the hinge and intracellular domains, such as CD3ζ and/or CD28. In addition to that fact, CAR-mediated NK cells require co-stimulatory molecules such as CD28, 4-1BB and CD134 in order to increase the proliferation and cytotoxicity effect against the solid tumor [16]. These cutting-edge approaches (CAR NK therapy) might be potential substitutes for the existing time-consuming technology CAR T-cell therapy. Here, CAR NK-cell therapy is more significant due to some basic criteria, for example, it is less expensive, easy to be isolated and secretes safer cytokines (IFN-γ and GM-CSF) [17]. Throughout the past years, many research groups have developed NK-92 cells for expressing different CARs, including CD19 and CD20 on B-cell leukemia/lymphoid, CD38 and CS-1 on pancreatic cancer and HER-2 for endothelial malignancy [18][19][20][21]. Additionally, CAR-modified NK-92 cells can always be injected orally, enabling them to migrate to targeted tumor tissue and exhibit their actual impact through a vaccine-like technique [22]. In addition, although transduction efficiency varies widely with primary NK cells, the translation of NK-92 cells is more consistent, contributing significantly to the homogeneity of the cell line. NK-92 cells have an average transduction efficiency from around 50%, even though non-viral techniques such as electrophoresis or nucleofection are used [23][24].

2.1.4. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy

CAR T-cell therapy depends on efficient, stable and safe gene transfer platforms. Cancer patient T cells can be isolated through leukapheresis and are harvested and genetically modified by ex vivo expansion through viral and non-viral transfection methods. The CAR T cell consists of the extracellular antigen-binding moieties that could be a single-chain fragment variable (scFv) portion consisting of the variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) chains of an antibody, and fused by a peptide spacer. It is interlinked to an intracellular signaling molecule/domain, i.e., TCR CD3ζ signaling chain or immune receptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-containing protein that are bound in tandem with co-stimulation signals such as CD28 or 4-1BB [25]. At the start of CAR T-cell therapy the focus is on the recognition of unprocessed antigens and carbohydrate, as well as glycolipid structures that are present on the tumor cells surface. However, both types of CAR T cells, such as CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells, are recruited and redirected to the target site of the cancer without the expression of MHC-I and MHC-II. These two effective T cells perform the major killing mechanism by cytolysis via perforin and granzyme secretion and, in some cases, follow the death mechanism by expressing the Fas/Fas-ligand (Fas-L) and/or TNF/TNF-receptor (TNF-R) [26]. Feins S et al. (2019) also illustrated that CAR T cells act against the CD19 protein of tumor cells of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and can diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and, thus, this T-cell therapy can be used for the treatment of cancers. Personalized cancer immunotherapy using engineered chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) gene-transduced T-cell (CAR T) therapies has shown significant potential in the development of highly personalized interventional cancer immunotherapy. The first FDA-approved CAR T therapy to treat re-occurring or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the US has recently been approved, named as Novartis’ Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel), which highlights the potential of CAR T-cell-based immunotherapy for the treatment of cancer [27]. With the ability to target different components of the tumor ecosystem, CAR T cells are an effective instrument to target different components of the tumor environment, including malignant cells and their microenvironment [28][29][30].

2.2. Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators are directly interlinked to the modification of the immune system and along with these stimulatory molecules enable checkpoint blockers [31], enhance cytokines secretion and act as an agonist for blocking cancer progression and enhancing the potential activity of immune cells. Basically, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) manifests on the surface of T cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs) and counteracts the activity of the T-cell co-stimulatory receptor (CD28). After recognition of the antigen, the CD28 molecules strongly amplify TCR signaling for the T cells activation. Here, we can clearly say that CD28 and/or CTLA-4 represent identical ligands such as CD80 and CD86 [32]. Notably, CTLA-4 has a higher affinity for both ligands (CD80 and CD86) and expression of the ligands on the surface of T cells dampens the activation of T cells by outcompeting CD28, as well as actively delivering inhibitory signals to the T cell [33]. On the contrary, programmed death-1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand-1 (PDL-1) play crucial roles in tumor progression and the survival of tumors in the tumor microenvironment. Mainly, PD-1 is found on several immune cells such as T cells, B cells, dendritic cells as well as monocytes [34]. Tumor cells and antigen-presenting cells express PDL-1 and interact with the T cells’ PD-1 and may cause T cell dysfunction, neutralization and exhaustion. It has been reported that PDL-1 is expressed on tumor cells and can escape the cytotoxic T cell-mediated cell killing and develop a tumor mass in the body [35]. However, when checkpoint inhibitors inhibit the pathway of PD-1/PDL-1 and CTL-4, they are capable of helping T cells to inhibit the advancement of tumor mass.

Cytokines are proteins or proteolytic enzymes secreted by immune cells that act as mediators of immunity and directly modulate immunomodulatory cells. Immunostimulatory cytokines such as IFNs, IL-2, IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18 are known to enhance immune responses against cancer [36]. The major cytokine IL-2 is able to promote the expansion of helper T cells (CD4+ T) and NK cells and facilitates the synthesis of Ig-type antibodies. The crucial role of IL-2 is in the Fas-mediated activation of CD4+ T cells that induce the cancerous cell’s death [37]. The research study by Dranoff G [38] reported that two major cytokines, namely IL-4 and IL-7, directly engage in the enhancement of the T cell’s function, but IL-4 activates eosinophil and eradicates the cancer cells from the body. IL-15 is needed for the activation, proliferation and cytotoxic action of NK cells and CD8+ T cells, which are able to release cytokines such as IFN-γ, leading to potential antitumor activity. Importantly, IFN-α is a specialized cytokine to use for the treatment of several malignancies and solid tumors through the maturation of dendritic cells and T lymphocytes [39]. Many research studies have now established our understanding of the immunological system and clinical evidence is available for the regulation of the immunologic reaction to malignancies. The role of bacille Calmette–Guerin (BCG) in the management of superficial bladder cancer has been demonstrated [40]. Intravenous BCG instillation causes an inflammatory reaction to the bladder epithelium that leads to inflammation cell recruitment and cytokine production [41]. Metastatic melanoma and renal cell cancer patients who receive IL-2 experience long-term responses, potentially cures [42]. Chemotherapy long-term survivors frequently relapse, while IL-2 responders always remain disease-free. Thus, immunomodulation appears to have been successful in priming the immune system to reject any recurrent tumor cells prior to the onset of clinical disease [43].

2.3. Antibody-Mediated Therapy

Antibodies are proteinaceous compounds that act against cell surface markers or antigens and protect us from several threats produced by B cells. Antibodies such as monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) have a significant cytotoxic effect against tumor cell surface antigens and modify the signal transduction cascade pathway within the tumor cells through the complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and/or antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [44]. In the CDC pathway, MAbs directly modulate the classic complement pathway, when the complement component C1 recognizes the fragment crystallizable region (Fc region) of antibodies and activates C3a, C3b. The C3a recruit immune effector cells at the complement activation site, but C5 convertase is activated by the complement component C3b via the activation of an alternative pathway that forms the membrane attack complex (MAC) to lysis the tumor cells [45]. The process of ADCC involves specific antibodies binding to the immune effector cells such as monocytes, NK cells and other leukocytes to kill the antigen specific tumor cells. Therapeutic antibodies engage with the Fc receptor of the immune effector cells via the Fc region of antibodies, for example, the MAbs Fc region attach the FcγRIII receptors on NK cells for activation and trigger the NK cell to secrete perforin and granzyme resulting in the death of cancer cells. Moreover, NK cells release proinflammatory cytokines due to the recruitment of adaptive immune cells and the inhibitory action plays against the cancer cells [46]. The research study by Christian P. Pallasch and his colleagues noted that the antibody-mediated therapy showed significant anticancer properties in the tumor microenvironment that possessed resistance activity toward several chemotherapeutic drugs [47]. Monoclonal antibody-mediated treatment induced tumor regression through apoptosis [48]. Jessica Marlind et al., 2008, [49] reported that in breast cancer treatment, the antibody-mediated insertion of IL-2 effectively enhanced the efficiency of chemotherapeutics drugs. In addition, several research studies have shown that the antibody-mediated therapy exhibits new promise for the potential treatment of pancreatic cancer and hepatocellular cancer [50][51].

2.4. Formation of Bi-Specific T Cell-Engaging Antibodies for Cancer Therapy

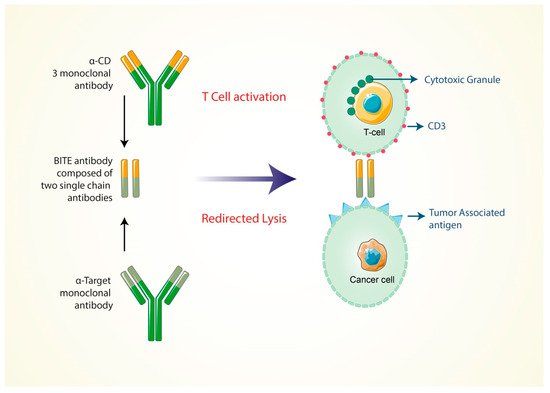

Many research activities have indicated that in both early and late phases of the diseases, T cells are capable of controlling the enhancement of tumor development and progression in cancer patients [52]. However, there are some difficulties because the T cell responses for tumor specific antigens are complex to develop and maintain in cancer patients. Moreover, when immunoediting is taking place, the responses are confined by some of the immune regulatory mechanisms for the selective tumor cells [53]. The production of antibodies is an effective strategy to assemble T cells for the immune-therapeutic treatment of cancers, and these types of antibodies are expressed both on the surface specific antigen of every type of cancer cells and for the CD3 complex on T cells. These types of antibodies are efficient at engaging with any kind of cytotoxic T cells to damage the cancer cells [54].

Independently, the production of antibodies can enhance the specificity of the T-cell receptor, co-stimulation or presentation of peptide antigens. Various research activities have demonstrated that, among bi-specific antibodies derived from T cells, the BITE (bi-specific T-cell engager) antibodies show a promising efficacy in the treatment of both bulky and minimal residual disease [54], and now it is FDA approved for treating several cancers. Kufer and colleagues’ research project showed that the special design of the CD3/target antigen-associated bi-specific antibodies has a very high rate of efficiency and can also involve CD8+ and CD4+T cells to redirect the cancer cell lysis process to the target (E–T ratio) ratios [55]. When the bi-specific antibodies bind only the CD3-specific branch, this shows low efficiency as the monovalent antibodies cannot trigger the T-cell signaling by CD3 (Figure 1). Contrary to this, the “bi-specific T-cell engager” (BITE) antibody is activated to the T cell through the multivalent strategy by the target cells [56][57]. In an in vitro study, the BITE antibody was found to be highly effective at redirecting the damaging response of cancer cells. Additionally, the drug’s potent antitumor activity has been demonstrated in a variety of animal models [58][59].

Figure 1. Formation of bi-specific T-cell engaging antibodies for cancer therapy. Bi-specific antibodies are specific for the CD3 and CD19 marker of cancer cells.

The BITE antibodies (MT110) were tested in a clinical trial with an ovarian cancer patient who, at late stage, had developed ovarian cancer cell metastasis [60]. Moreover, they were tested as a stage 2 clinical trial of cancer patients who had b-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-All) and showed minimum accessorial disease in the patient’s bone marrow [61]. Another BITE antibody, named as MTT110, which is now in the clinical development phase, is bi-specific only, especially for the CD3 complex and the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) [62]. It is currently being clinically tested in patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancer as a part of the clinical trial one. The expression efficiency of the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) has, therefore, been shown to be high on several squamous cell carcinoma types, human adenocarcinoma and cancer stem cells. It has certain limitations because the animal model did not identify the CD3 modulation of T cells by treating BITE antibodies to suppress the cytotoxic granules of T cells [63].

2.5. Formation of Cancer Vaccine

Cancer treatment vaccines enhance the immune system’s capability to signify and damage the cancer antigens more effectively. Cancer cell’s possess specific molecules, named cancer specific antigens, for every type of cancer cell on their cell surface, but they are absent in healthy cells. Generally, cancer vaccines can be produced for individual cancer patients. These categories of cancer vaccines are composed from the tumor sample of the individual cancer patient (Figure 2). For that, surgery is required to find a large enough sample of the tumor cells to make the vaccine against these cancer cells. There are two types of vaccine in cancer treatment. They are the personalized cancer vaccine and the vaccine to target specific cancer antigens [64].

Figure 2. The steps for the formation of cancer vaccine. A surface protein found on the surface of cancer cells and vaccine developed depending on the structure of that protein. Here, the DNA with modified gene will be inserted into the cancer cells by using irradiation of the cancer cells.

Even if cancers can be originated by common mechanisms that are regulated by the mutated genes in the process of cell transformation (i.e., p53, ras), they pass through excessive random mutations in other genes. The expression of foreign antigens is regulated by these mutations and by making a molecular “fingerprint” that absolutely distinguishes the patient’s tumor. Whereas the mutations of genes are regulated indiscriminately, the antigenic fingerprint of one person’s cancer is generally not the same as another person’s cancer. In this way, the particular cancers among the identical pathological group are independent based on their antigens. These essential characteristics demand that the immune system of individual patient’s has to be treated to identify the specific cancer antigens and cancer cells. The novel approaches for generating cancer immune-therapeutics are known as the autologous tumor cell vaccines, allogeneic tumor cell vaccines, dendritic cell vaccines, protein- or peptide-based cancer vaccines, genetic vaccines and the whole tumor lysates [65][66].

The cancer vaccine possesses an effective activity to provide immunity towards the cancer antigens. The response stimulates the activity of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to trigger the functions of T helper cells to provide the antibody against the cancer antigens and also activate the effector or cytotoxic T cells. However, cancer vaccines have some limitations: because the tumor cells or cancer cells express random specific types of antigens, these antigen’s type is not fixed. For that reason, cancer vaccines are not so effective for inhibiting the growth of the cancer cells.

References

- Met, Ö.; Jensen, K.M.; Chamberlain, C.A.; Donia, M.; Svane, I.M. Principles of adoptive T cell therapy in cancer. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 49–58.

- Vonderheide, R.H.; June, C.H. Engineering T cells for cancer: Our synthetic future. Immunol. Rev. 2014, 257, 7–13.

- Andersen, R.; Donia, M.; Westergaard, M.C.; Pedersen, M.; Hansen, M.; Svane, I.M. Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte therapy for ovarian cancer and renal cell carcinoma. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015, 11, 2790–2795.

- Azimi, F.; Scolyer, R.A.; Rumcheva, P.; Moncrieff, M.; Murali, R.; McCarthy, S.W.; Saw, R.P.; Thompson, J.F. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte grade is an independent predictor of sentinel lymph node status and survival in patients with cutaneous melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2678–2683.

- Sakellariou-Thompson, D.; Forget, M.A.; Hinchcliff, E.; Celestino, J.; Hwu, P.; Jazaeri, A.A.; Haymaker, C.; Bernatchez, C. Potential clinical application of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy for ovarian epithelial cancer prior or post-resistance to chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII 2019, 68, 1747–1757.

- Buisseret, L.; Garaud, S.; de Wind, A.; Van den Eynden, G.; Boisson, A.; Solinas, C.; Gu-Trantien, C.; Naveaux, C.; Lodewyckx, J.N.; Duvillier, H.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte composition, organization and PD-1/ PD-L1 expression are linked in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1257452.

- Chung, Y.R.; Kim, H.J.; Jang, M.H.; Park, S.Y. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocyte subsets in breast cancer depends on hormone receptor status. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 161, 409–420.

- Ping, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y. T-cell receptor-engineered T cells for cancer treatment: Current status and future directions. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 254–266.

- Fesnak, A.D.; June, C.H.; Levine, B.L. Engineered T cells: The promise and challenges of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 566–581.

- Rosenberg, S.A.; Restifo, N.P. Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer. Science 2015, 348, 62–68.

- Johnson, L.A.; Morgan, R.A.; Dudley, M.E.; Cassard, L.; Yang, J.C.; Hughes, M.S.; Kammula, U.S.; Royal, R.E.; Sherry, R.M.; Wunderlich, J.R.; et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood 2009, 114, 535–546.

- Chodon, T.; Comin-Anduix, B.; Chmielowski, B.; Koya, R.C.; Wu, Z.; Auerbach, M.; Ng, C.; Avramis, E.; Seja, E.; Villanueva, A.; et al. Adoptive transfer of MART-1 T-cell receptor transgenic lymphocytes and dendritic cell vaccination in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2457–2465.

- Robbins, P.F.; Morgan, R.A.; Feldman, S.A.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Dudley, M.E.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Nahvi, A.V.; Helman, L.J.; Mackall, C.L.; et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 917–924.

- Rapoport, A.P.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Binder-Scholl, G.K.; Goloubeva, O.; Vogl, D.T.; Lacey, S.F.; Badros, A.Z.; Garfall, A.; Weiss, B.; Finklestein, J.; et al. NY-ESO-1-specific TCR-engineered T cells mediate sustained antigen-specific antitumor effects in myeloma. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 914–921.

- Robbins, P.F.; Kassim, S.H.; Tran, T.L.; Crystal, J.S.; Morgan, R.A.; Feldman, S.A.; Yang, J.C.; Dudley, M.E.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Sherry, R.M.; et al. A pilot trial using lymphocytes genetically engineered with an NY-ESO-1-reactive T-cell receptor: Long-term follow-up and correlates with response. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1019–1027.

- Rezvani, K. Adoptive cell therapy using engineered natural killer cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019, 54, 785–788.

- Hu, W.; Wang, G.; Huang, D.; Sui, M.; Xu, Y. Cancer Immunotherapy Based on Natural Killer Cells: Current Progress and New Opportunities. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1205.

- Romanski, A.; Uherek, C.; Bug, G.; Seifried, E.; Klingemann, H.; Wels, W.S.; Ottmann, O.G.; Tonn, T. CD19-CAR engineered NK-92 cells are sufficient to overcome NK cell resistance in B-cell malignancies. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 1287–1294.

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, W.; Shang, P.; Zhang, H.; Fu, W.; Ye, F.; Zeng, T.; Huang, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, W.; et al. Transfection of chimeric anti-CD138 gene enhances natural killer cell activation and killing of multiple myeloma cells. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 297–310.

- Chu, J.; Deng, Y.; Benson, D.M.; He, S.; Hughes, T.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Y.; Mao, H.; Yi, L.; Ghoshal, K.; et al. CS1-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered natural killer cells enhance in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against human multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2014, 28, 917–927.

- Schönfeld, K.; Sahm, C.; Zhang, C.; Naundorf, S.; Brendel, C.; Odendahl, M.; Nowakowska, P.; Bönig, H.; Köhl, U.; Kloess, S.; et al. Selective inhibition of tumor growth by clonal NK cells expressing an ErbB2/HER2-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2015, 23, 330–338.

- Rezvani, K.; Rouce, R.; Liu, E.; Shpall, E. Engineering Natural Killer Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2017, 25, 1769–1781.

- Boissel, L.; Betancur-Boissel, M.; Lu, W.; Krause, D.S.; Van Etten, R.A.; Wels, W.S.; Klingemann, H. Retargeting NK-92 cells by means of CD19- and CD20-specific chimeric antigen receptors compares favorably with antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e26527.

- Rubnitz, J.E.; Inaba, H.; Ribeiro, R.C.; Pounds, S.; Rooney, B.; Bell, T.; Pui, C.H.; Leung, W. NKAML: A pilot study to determine the safety and feasibility of haploidentical natural killer cell transplantation in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 955–959.

- Miliotou, A.N.; Papadopoulou, L.C. CAR T-cell Therapy: A New Era in Cancer Immunotherapy. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2018, 19, 5–18.

- Feins, S.; Kong, W.; Williams, E.F.; Milone, M.C.; Fraietta, J.A. An introduction to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, S3–S9.

- Prasad, V. Immunotherapy: Tisagenlecleucel—The first approved CAR-T-cell therapy: Implications for payers and policy makers. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 11–12.

- Fujiwara, H. Adoptive immunotherapy for hematological malignancies using T cells gene-modified to express tumor antigen-specific receptors. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 1049–1068.

- Park, J.H.; Geyer, M.B.; Brentjens, R.J. CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapeutics for hematologic malignancies: Interpreting clinical outcomes to date. Blood 2016, 127, 3312–3320.

- Maus, M.V.; Grupp, S.A.; Porter, D.L.; June, C.H. Antibody-modified T cells: CARs take the front seat for hematologic malignancies. Blood 2014, 123, 2625–2635.

- Marin-Acevedo, J.A.; Soyano, A.E.; Dholaria, B.; Knutson, K.L.; Lou, Y. Cancer immunotherapy beyond immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 8.

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264.

- Sasidharan Nair, V.; Elkord, E. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy: A focus on T-regulatory cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2018, 96, 21–33.

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, M.; Nie, H.; Yuan, Y. PD-1 and PD-L1 in cancer immunotherapy: Clinical implications and future considerations. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 1111–1122.

- Alsaab, H.O.; Sau, S.; Alzhrani, R.; Tatiparti, K.; Bhise, K.; Kashaw, S.K.; Iyer, A.K. PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Signaling Inhibition for Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanism, Combinations, and Clinical Outcome. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 561.

- Weiss, J.M.; Subleski, J.J.; Wigginton, J.M.; Wiltrout, R.H. Immunotherapy of cancer by IL-12-based cytokine combinations. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2007, 7, 1705–1721.

- Waldmann, T.A. Cytokines in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10.

- Dranoff, G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 11–22.

- Berraondo, P.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Ochoa, M.C.; Etxeberria, I.; Aznar, M.A.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.E.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Castañón, E.; Melero, I. Cytokines in clinical cancer immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 6–15.

- Parekh, D.J.; Bochner, B.H.; Dalbagni, G. Superficial and muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Principles of management for outcomes assessments. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5519–5527.

- Bettex-Galland, M.; Studer, U.E.; Walz, A.; Dewald, B.; Baggiolini, M. Neutrophil-activating peptide-1/interleukin-8 detection in human urine during acute bladder inflammation caused by transurethral resection of superficial cancer and bacillus Calmette-Guérin administration. Eur. Urol. 1991, 19, 171–175.

- Rosenberg, S.A.; Yang, J.C.; White, D.E.; Steinberg, S.M. Durability of complete responses in patients with metastatic cancer treated with high-dose interleukin-2: Identification of the antigens mediating response. Ann. Surg. 1998, 228, 307–319.

- Thotathil, Z.; Jameson, M.B. Early experience with novel immunomodulators for cancer treatment. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2007, 16, 1391–1403.

- Scott, A.M.; Wolchok, J.D.; Old, L.J. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 278–287.

- Hafeez, U.; Gan, H.K.; Scott, A.M. Monoclonal antibodies as immunomodulatory therapy against cancer and autoimmune diseases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2018, 41, 114–121.

- Adams, G.P.; Weiner, L.M. Monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 1147–1157.

- Pallasch, C.P.; Leskov, I.; Braun, C.J.; Vorholt, D.; Drake, A.; Soto-Feliciano, Y.M.; Bent, E.H.; Schwamb, J.; Iliopoulou, B.; Kutsch, N.; et al. Sensitizing protective tumor microenvironments to antibody-mediated therapy. Cell 2014, 156, 590–602.

- Trauth, B.C.; Klas, C.; Peters, A.M.; Matzku, S.; Möller, P.; Falk, W.; Debatin, K.M.; Krammer, P.H. Monoclonal antibody-mediated tumor regression by induction of apoptosis. Science 1989, 245, 301–305.

- Mårlind, J.; Kaspar, M.; Trachsel, E.; Sommavilla, R.; Hindle, S.; Bacci, C.; Giovannoni, L.; Neri, D. Antibody-mediated delivery of interleukin-2 to the stroma of breast cancer strongly enhances the potency of chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 6515–6524.

- Dakhel, S.; Padilla, L.; Adan, J.; Masa, M.; Martinez, J.M.; Roque, L.; Coll, T.; Hervas, R.; Calvis, C.; Messeguer, R.; et al. S100P antibody-mediated therapy as a new promising strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Oncogenesis 2014, 3, e92.

- Xiao, Z.; Chung, H.; Banan, B.; Manning, P.T.; Ott, K.C.; Lin, S.; Capoccia, B.J.; Subramanian, V.; Hiebsch, R.R.; Upadhya, G.A.; et al. Antibody mediated therapy targeting CD47 inhibits tumor progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015, 360, 302–309.

- Krishnamurthy, A.; Jimeno, A. Bispecific antibodies for cancer therapy: A review. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 185, 122–134.

- Runcie, K.; Budman, D.R.; John, V.; Seetharamu, N. Bi-specific and tri-specific antibodies- the next big thing in solid tumor therapeutics. Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 50.

- Dreier, T.; Lorenczewski, G.; Brandl, C.; Hoffmann, P.; Syring, U.; Hanakam, F.; Kufer, P.; Riethmuller, G.; Bargou, R.; Baeuerle, P.A. Extremely potent, rapid and costimulation-independent cytotoxic T-cell response against lymphoma cells catalyzed by a single-chain bispecific antibody. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 100, 690–697.

- Brischwein, K.; Parr, L.; Pflanz, S.; Volkland, J.; Lumsden, J.; Klinger, M.; Locher, M.; Hammond, S.A.; Kiener, P.; Kufer, P.; et al. Strictly target cell-dependent activation of T cells by bispecific single-chain antibody constructs of the BiTE class. J. Immunother. 2007, 30, 798–807.

- Roumenina, L.T.; Daugan, M.V.; Petitprez, F.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Fridman, W.H. Context-dependent roles of complement in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 698–715.

- Baeuerle, P.A.; Kufer, P.; Bargou, R. BiTE: Teaching antibodies to engage T-cells for cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2009, 11, 22–30.

- Bargou, R.; Leo, E.; Zugmaier, G.; Klinger, M.; Goebeler, M.; Knop, S.; Noppeney, R.; Viardot, A.; Hess, G.; Schuler, M.; et al. Tumor regression in cancer patients by very low doses of a T cell-engaging antibody. Science 2008, 321, 974–977.

- Hoffman, L.M.; Gore, L. Blinatumomab, a Bi-Specific Anti-CD19/CD3 BiTE(®) Antibody for the Treatment of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Perspectives and Current Pediatric Applications. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 63.

- Brischwein, K.; Schlereth, B.; Guller, B.; Steiger, C.; Wolf, A.; Lutterbuese, R.; Offner, S.; Locher, M.; Urbig, T.; Raum, T.; et al. MT110: A novel bispecific single-chain antibody construct with high efficacy in eradicating established tumors. Mol. Immunol. 2006, 43, 1129–1143.

- Maetzel, D.; Denzel, S.; Mack, B.; Canis, M.; Went, P.; Benk, M.; Kieu, C.; Papior, P.; Baeuerle, P.A.; Munz, M.; et al. Nuclear signalling by tumour-associated antigen EpCAM. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 162–171.

- Ran, F.A.; Cong, L.; Yan, W.X.; Scott, D.A.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Kriz, A.J.; Zetsche, B.; Shalem, O.; Wu, X.; Makarova, K.S.; et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature 2015, 520, 186–191.

- Swiech, L.; Heidenreich, M.; Banerjee, A.; Habib, N.; Li, Y.; Trombetta, J.; Sur, M.; Zhang, F. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 102–106.

- Saxena, M.; van der Burg, S.H.; Melief, C.J.M.; Bhardwaj, N. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 360–378.

- Guo, C.; Manjili, M.H.; Subjeck, J.R.; Sarkar, D.; Fisher, P.B.; Wang, X.-Y. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: Past, present, and future. Adv. Cancer Res. 2013, 119, 421–475.

- Jain, K.K. Personalized cancer vaccines. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 1637–1647.

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

952

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

10 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No