| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xuewei Zhu | + 3012 word(s) | 3012 | 2020-08-13 11:02:48 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | -1614 word(s) | 1398 | 2020-08-24 06:26:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

As a critical component of the innate immune system, the nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome can be activated by various endogenous and exogenous danger signals. Activation of this cytosolic multiprotein complex triggers the release of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 and initiates pyroptosis, an inflammatory form of programmed cell death. The NLRP3 inflammasome fuels both chronic and acute inflammatory conditions and is critical in the emergence of inflammaging. Recent advances have highlighted that various metabolic pathways converge as potent regulators of the NLRP3 inflammasome. This review focuses on our current understanding of the metabolic regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and the contribution of the NLRP3 inflammasome to inflammaging.

1. Definition

The NLRP3 inflammasome is composed of the sensor NLRP3, the adaptor ASC, and the effector caspase-1.

2. Introduction

Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages occurs in two steps, each with a different activating signal [1–6]. First, macrophages are primed through the recognition of an initial “danger” signal (Signal 1), which induces the transcription and production of inactive pro-IL-1β and NLRP3, which is subsequently ubiquitinated. Typically, the recognition of the bacterial cell wall component lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a pathogen associated molecular patter (PAMP), by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) acts as a priming signal for innate immune cells such as monocytes or macrophages and activates transcription via NF-κB. Second, the recognition of a second activation signal initiates assembly of the inflammasome complex (Signal 2). Second signals are notably diverse, such as mitochondrial oxidative damage, lysosomal membrane rupture, and plasma membrane potassium efflux [1][2][3][4][5][6]. Currently, how macrophages assemble the inflammasome complex in response to a variety of danger signals is still not entirely clear [5], but interestingly, several cellular metabolic pathways have been implicated in both stages of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In this review, we will focus on the current understanding of how cellular metabolism regulates the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and then discuss its implications on our understanding of inflammatory diseases and “inflammaging”.

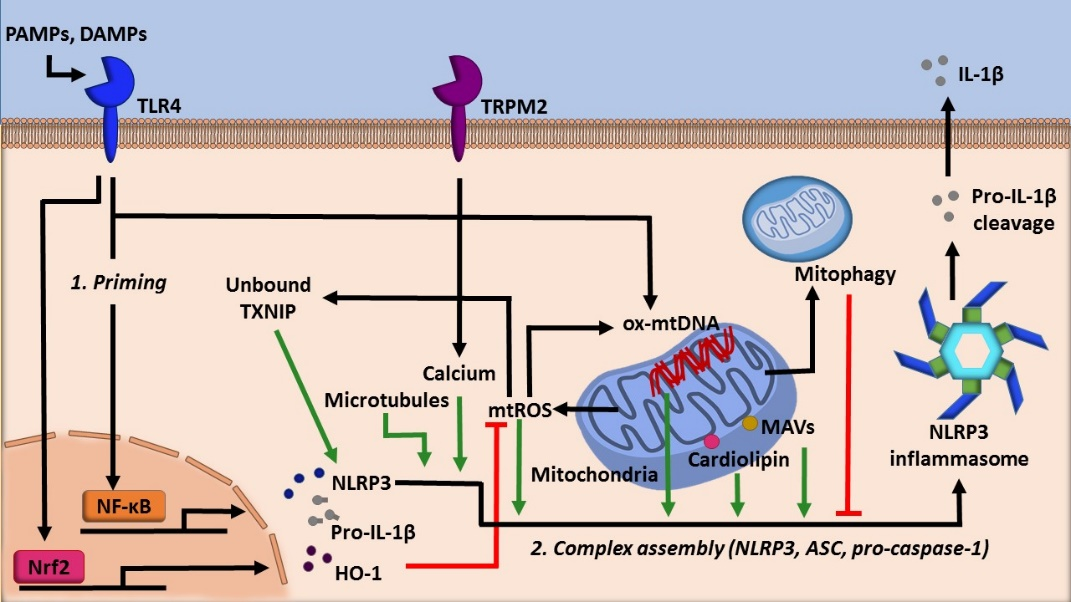

3. Mitochondria as the central metabolic organelle

Mitochondria, well known as the powerhouse of the cell, act as a critical regulator of many cellular processes such as cell death, cellular signaling, and energetic homeostasis [7]. Mitochondrial dynamics, such as number and location, profoundly influence the metabolic status of a cell [8]. Inflammasomes are highly tuned to this as well. Evidence has shown that the NLRP3 inflammasome utilizes several mitochondria centric mechanisms to assemble (Figure 1). Firstly, NLRP3 possesses an N-terminal sequence that allows for it to localize to the mitochondria. Upon activation, components of the NLRP3 inflammasome translocate to mitochondria, an event dependent by the adaptor protein mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) [9]. Microtubules also promote the localization of the NLRP3 inflammasome to the mitochondria in the presence of activating signals by mediating the association of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC) on the mitochondria to NLRP3 [10]. The association of ASC and NLRP3 was also shown to be facilitated by calcium flux [11]. Finally, this localization is facilitated by cardiolipin, a mitochondria specific phospholipid. Cardiolipin can translocate from the inner mitochondrial membrane to the outer mitochondrial membrane, where cardiolipin directly binds NLRP3 to promote its activation [12].

Figure 1. The role of mitochondria in regulating NLRP3 activity.

Furthermore, in eukaryotic cells, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated by NADPH oxidases (NOXs) as well as via mitochondrial respiration and other metabolic processes [13][14]. Mitochondrial ROS is a potent NLRP3 inflammasome activator and is one indicator of cellular stress [15]. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is also shown to promote inflammasome activation (Figure 1). Mitochondrial damage following environmental or metabolic stress induces oxidation of mtDNA. Oxidized mtDNA can be released into the cytosol, where it binds NLRP3, leading to inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion [7]. More recently, it has been demonstrated that specifically, newly synthesized mtDNA is critical for the NLRP3 inflammasome activation [16].

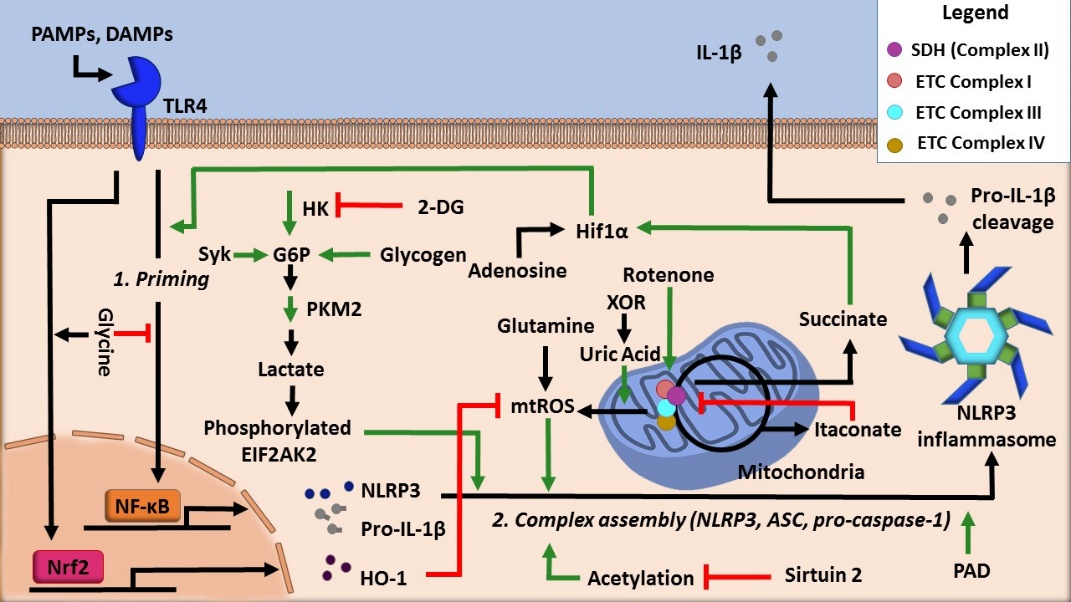

Moreover, the production of ATP in the mitochondria via oxidative phosphorylation is a process intimately linked with the inflammasome activity. For example, acute immune activation the suppression of oxidative phosphorylation-mediated ATP production favors Warburg glycolysis, a state that is coupled with increased succinate levels [17]. Notably, both of these changes facilitate NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activity by cellular metabolic pathways.

4. Carbohydrates and glycolysis

To date, it is still unclear whether glycolytic flux positively or negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activity. Some studies show that the inhibition of glycolytic flux attenuates the inflammasome. For example, one study showed that treatment of classically activated macrophages with aminooxyacetic acid, an inhibitor of aspartate aminotransferase, decreases glycolysis, concurrently reducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation [18]. Seemingly in conflict with these observations, a study demonstrated that the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages is inversely related to glycolysis such that inhibition of glycolysis activates the NLRP3 inflammasome [19]. Further investigations are needed to understand this discrepancy as to whether glycolysis promotes or attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nonetheless, cellular conditions such as cellular redox balance and metabolite prevalence may play a broader role in this regulation.

With this discrepancy in mind, several glycolysis regulators have been implicated in controlling the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome (Figure 2). Hexokinase, a glycolytic enzyme that adds a phosphate group onto glucose to initiate glycolysis, was shown to be essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation by activating glycolytic flux [20]. Another well-known regulator is pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), which is responsible for catalyzing the final rate-limiting step of glycolysis. One study found that inflammasome activation is dependent on the activity of PKM2. IL-1β secretion resulted from PKM2-dependent lactate production, which promoted phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 2 (EIF2AK2), a protein that is known to be implicated in inflammasome activation [21].

5. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammaging

Akin to the inflammation of chronic inflammatory conditions, inflammaging is the long term, low-grade immune activation from sterile sources that develops with aging. This type of inflammation contributes to the aging process [22], following a lifetime of inflammation from origins such as the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Two well-characterized conditions, in which the aberrant activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to and exacerbates pathology, leading to inflammaging, are obesity and diabetes. Obesity and specifically obesity-associated insulin resistance have been linked to the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome [23][24]. Saturated fatty acids such as palmitate, which are enriched in high-fat diet, activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, driving insulin resistance [25]. NLRP3-dependent IL-1β secretion has been shown to impair pancreatic beta cell function [23][24][26], adipocyte function, and insulin sensitivity [27], promoting the progression of obesity and insulin resistance. The deletion of NLRP3 or inhibition of caspase-1 in mice was shown to improve insulin sensitivity and ameliorate obesity-associated pathologies [25][27][28]. Moreover, obesity accelerates age-related thymic atrophy and decreases T cell diversity [29]. Elimination of NLRP3 or ASC attenuates this age-related thymic atrophy and promotes T cell repertoire diversity [30]. In addition to the dysregulation of T cell homeostasis, age-associated B cell expansion in adipose tissues impairs tissue metabolism and promotes visceral adiposity in the elderly, a process regulated by the NLRP3 inflammasome [31]. Together, these two studies suggest that targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome has a potential beneficial effect on the re-establishment of immune competence in the elderly. Lastly, it was reported that individuals over 85 years of age could be stratified into two groups based on their expression level of inflammasome gene modules, as either constitutive or non-constitutive. The former group was associated with measures of all-cause mortality, again supporting the concept that targeting inflammasome components may ameliorate chronic inflammation and various other age-associated conditions [32].

Atherosclerosis is another condition in which the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome promotes pathogenesis. Atherogenic factors such as cholesterol crystals [33] and oxidized LDL [34] activate the NRLP3 inflammasome. Deletion or inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex, including NLRP3, ASC, or IL-1β, was shown to improve lipid metabolism, and to decrease inflammation, pyroptosis, and infiltration of more immune cells into plaques, thus ameliorating inflammatory responses and atherosclerosis progression [33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43].

Chronic NLRP3 inflammasome activity was shown to be exacerbated by defective autophagy in aged individuals, and enhancement of autophagy improves health outcomes [44]. Importantly, healthy metabolic status, such as the maintenance of SIRT2 activity, has been shown to have beneficial impacts on aging. Aging reduces SIRT2 expression and increases mitochondrial stress, leading to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in hematopoietic stem cells [45]. This age-driven functionality decline of hematopoietic stem cells was countered by SIRT2 overexpression, or NLRP3 inactivation [45]. Additionally, the activity of SIRT2 can prevent NLRP3 inflammasome-induced cell death [10]. In line with these findings, increased NAD+ levels along with sirtuin activation have been shown to improve mitochondrial homeostasis, organ function, and lifespan [46].

References

- Lamkanfi, M.; Dixit, V.M. Mechanisms and Functions of Inflammasomes. Cell 2014, 157, 1013–1022, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.007.

- Henao-Mejia, J.; Elinav, E.; Thaiss, C.A.; Flavell, R.A. Inflammasomes and Metabolic Disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2014, 76, 57–78, doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170324.

- Rathinam, V.A.K.; Vanaja, S.K.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Regulation of inflammasome signaling. Nat Immunol 2012, 13, 333–332, doi:10.1038/ni.2237.

- Lamkanfi, M.; Dixit, V.M. Inflammasomes and Their Roles in Health and Disease. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 2012, 28, 137–161, doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155745.

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P.-Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nature Reviews Immunology 2019, 19, 477–489, doi:10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0.

- Mangan, M.S.J.; Olhava, E.J.; Roush, W.R.; Seidel, H.M.; Glick, G.D.; Latz, E. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 588–606, doi:10.1038/nrd.2018.97.

- Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg, H.; Ouchida, A.T.; Norberg, E. The role of mitochondria in metabolism and cell death. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2017, 482, 426–431, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.088.

- Mishra, P.; Chan, D.C. Metabolic regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. J Cell Biol 2016, 212, 379–387, doi:10.1083/jcb.201511036.

- Subramanian, N.; Natarajan, K.; Clatworthy, M.R.; Wang, Z.; Germain, R.N. The Adaptor MAVS Promotes NLRP3 Mitochondrial Localization and Inflammasome Activation. Cell 2013, 153, 348–361, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.054.

- Misawa, T.; Takahama, M.; Kozaki, T.; Lee, H.; Zou, J.; Saitoh, T.; Akira, S. Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 454–460, doi:10.1038/ni.2550.

- Elliott, E.I.; Miller, A.N.; Banoth, B.; Iyer, S.S.; Stotland, A.; Weiss, J.P.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Cassel, S.L. Cutting Edge: Mitochondrial Assembly of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Complex Is Initiated at Priming. The Journal of Immunology 2018, ji1701723, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1701723.

- Iyer, S.S.; He, Q.; Janczy, J.R.; Elliott, E.I.; Zhong, Z.; Olivier, A.K.; Sadler, J.J.; Knepper-Adrian, V.; Han, R.; Qiao, L.; et al. Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 2013, 39, 311–323, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.001.

- Kalogeris, T.; Bao, Y.; Korthuis, R.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: A double edged sword in ischemia/reperfusion vs preconditioning. Redox Biol 2014, 2, 702–714, doi:10.1016/j.redox.2014.05.006.

- Dan Dunn, J.; Alvarez, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Soldati, T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: A nexus of cellular homeostasis. Redox Biol 2015, 6, 472–485, doi:10.1016/j.redox.2015.09.005.

- Spinelli, J.B.; Haigis, M.C. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nature Cell Biology 2018, 20, 745–754, doi:10.1038/s41556-018-0124-1.

- Zhong, Z.; Liang, S.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; He, F.; Shalapour, S.; Lin, X.; Wong, J.; Ding, S.; Seki, E.; Schnabl, B.; et al. New mitochondrial DNA synthesis enables NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2018, 560, 198–203, doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0372-z.

- Mills, E.L.; Kelly, B.; Logan, A.; Costa, A.S.H.; Varma, M.; Bryant, C.E.; Tourlomousis, P.; Däbritz, J.H.M.; Gottlieb, E.; Latorre, I.; et al. Succinate Dehydrogenase Supports Metabolic Repurposing of Mitochondria to Drive Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell 2016, 167, 457-470.e13, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.064.

- Zhao, P.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, L.; Shen, Z.; Chen, W.; Hui, J. Aminooxyacetic acid attenuates post-infarct cardiac dysfunction by balancing macrophage polarization through modulating macrophage metabolism in mice. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 2593–2609, doi:10.1111/jcmm.14972.

- Sanman, L.E.; Qian, Y.; Eisele, N.A.; Ng, T.M.; van der Linden, W.A.; Monack, D.M.; Weerapana, E.; Bogyo, M. Disruption of glycolytic flux is a signal for inflammasome signaling and pyroptotic cell death. Elife 2016, 5, e13663, doi:10.7554/eLife.13663.

- Moon, J.-S.; Hisata, S.; Park, M.-A.; DeNicola, G.M.; Ryter, S.W.; Nakahira, K.; Choi, A.M.K. mTORC1-Induced HK1-Dependent Glycolysis Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Cell Rep 2015, 12, 102–115, doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.046.

- Xie, M.; Yu, Y.; Kang, R.; Zhu, S.; Yang, L.; Zeng, L.; Sun, X.; Yang, M.; Billiar, T.R.; Wang, H.; et al. PKM2-dependent glycolysis promotes NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome activation. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 1–13, doi:10.1038/ncomms13280.

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: a new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2018, 14, 576–590, doi:10.1038/s41574-018-0059-4.

- Zhou, R.; Tardivel, A.; Thorens, B.; Choi, I.; Tschopp, J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nature Immunology 2010, 11, 136–140, doi:10.1038/ni.1831.

- Masters, S.L.; Dunne, A.; Subramanian, S.L.; Hull, R.L.; Tannahill, G.M.; Sharp, F.A.; Becker, C.; Franchi, L.; Yoshihara, E.; Chen, Z.; et al. Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL-1β in type 2 diabetes. Nat Immunol 2010, 11, 897–904, doi:10.1038/ni.1935.

- Wen, H.; Gris, D.; Lei, Y.; Jha, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, M.T.-H.; Brickey, W.J.; Ting, J.P.-Y. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 408–415, doi:10.1038/ni.2022.

- Maedler, K.; Sergeev, P.; Ris, F.; Oberholzer, J.; Joller-Jemelka, H.I.; Spinas, G.A.; Kaiser, N.; Halban, P.A.; Donath, M.Y. Glucose-induced β cell production of IL-1β contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. J Clin Invest 2002, 110, 851–860, doi:10.1172/JCI15318.

- Stienstra, R.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Koenen, T.; van Tits, B.; van Diepen, J.A.; van den Berg, S.A.A.; Rensen, P.C.N.; Voshol, P.J.; Fantuzzi, G.; Hijmans, A.; et al. The Inflammasome-Mediated Caspase-1 Activation Controls Adipocyte Differentiation and Insulin Sensitivity. Cell Metab 2010, 12, 593–605, doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.011.

- Vandanmagsar, B.; Youm, Y.-H.; Ravussin, A.; Galgani, J.E.; Stadler, K.; Mynatt, R.L.; Ravussin, E.; Stephens, J.M.; Dixit, V.D. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nature Medicine 2011, 17, 179–188, doi:10.1038/nm.2279.

- Yang, H.; Youm, Y.-H.; Vandanmagsar, B.; Rood, J.; Kumar, K.G.; Butler, A.A.; Dixit, V.D. Obesity accelerates thymic aging. Blood 2009, 114, 3803–3812, doi:10.1182/blood-2009-03-213595.

- Youm, Y.-H.; Kanneganti, T.-D.; Vandanmagsar, B.; Zhu, X.; Ravussin, A.; Adijiang, A.; Owen, J.S.; Thomas, M.J.; Francis, J.; Parks, J.S.; et al. The NLRP3 Inflammasome Promotes Age-Related Thymic Demise and Immunosenescence. Cell Reports 2012, 1, 56–68, doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2011.11.005.

- Camell, C.D.; Günther, P.; Lee, A.; Goldberg, E.L.; Spadaro, O.; Youm, Y.-H.; Bartke, A.; Hubbard, G.B.; Ikeno, Y.; Ruddle, N.H.; et al. Aging Induces an Nlrp3 Inflammasome-Dependent Expansion of Adipose B Cells That Impairs Metabolic Homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 1024-1039.e6, doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.10.006.

- Furman, D.; Chang, J.; Lartigue, L.; Bolen, C.R.; Haddad, F.; Gaudilliere, B.; Ganio, E.A.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Spitzer, M.H.; Douchet, I.; et al. Expression of specific inflammasome gene modules stratifies older individuals into two extreme clinical and immunological states. Nat Med 2017, 23, 174–184, doi:10.1038/nm.4267.

- Duewell, P.; Kono, H.; Rayner, K.J.; Sirois, C.M.; Vladimer, G.; Bauernfeind, F.G.; Abela, G.S.; Franchi, L.; Nuñez, G.; Schnurr, M.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 2010, 464, 1357–1361, doi:10.1038/nature08938.

- Sheedy, F.J.; Grebe, A.; Rayner, K.J.; Kalantari, P.; Ramkhelawon, B.; Carpenter, S.B.; Becker, C.E.; Ediriweera, H.N.; Mullick, A.E.; Golenbock, D.T.; et al. CD36 coordinates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by facilitating the intracellular nucleation from soluble to particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 812–820, doi:10.1038/ni.2639.

- Zheng, F.; Xing, S.; Gong, Z.; Mu, W.; Xing, Q. Silence of NLRP3 Suppresses Atherosclerosis and Stabilizes Plaques in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice. Mediators Inflamm 2014, 2014, doi:10.1155/2014/507208.

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Mu, N.; Lou, X.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Fan, D.; Tan, H. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes contributes to hyperhomocysteinemia-aggravated inflammation and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. Laboratory Investigation 2017, 97, 922–934, doi:10.1038/labinvest.2017.30.

- Xi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, W.Y.; Jiang, X.; Sha, X.; Cheng, X.; Wang, J.; Qin, X.; Yu, J.; et al. Caspase-1 Inflammasome Activation Mediates Homocysteine-Induced Pyrop-Apoptosis in Endothelial Cells. Circ Res 2016, 118, 1525–1539, doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308501.

- Elhage R.; Maret A.; Pieraggi M.-T.; Thiers J. C.; Arnal J. F.; Bayard F. Differential Effects of Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist and Tumor Necrosis Factor Binding Protein on Fatty-Streak Formation in Apolipoprotein E–Deficient Mice. Circulation 1998, 97, 242–244, doi:10.1161/01.CIR.97.3.242.

- Kirii Hirokazu; Niwa Tamikazu; Yamada Yasuhiro; Wada Hisayasu; Saito Kuniaki; Iwakura Yoichiro; Asano Masahide; Moriwaki Hisataka; Seishima Mitsuru Lack of Interleukin-1β Decreases the Severity of Atherosclerosis in ApoE-Deficient Mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2003, 23, 656–660, doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000064374.15232.C3.

- Bhaskar, V.; Yin, J.; Mirza, A.M.; Phan, D.; Vanegas, S.; Issafras, H.; Michelson, K.; Hunter, J.J.; Kantak, S.S. Monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-1 beta reduce biomarkers of atherosclerosis in vitro and inhibit atherosclerotic plaque formation in Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2011, 216, 313–320, doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.02.026.

- Usui, F.; Shirasuna, K.; Kimura, H.; Tatsumi, K.; Kawashima, A.; Karasawa, T.; Hida, S.; Sagara, J.; Taniguchi, S.; Takahashi, M. Critical role of caspase-1 in vascular inflammation and development of atherosclerosis in Western diet-fed apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2012, 425, 162–168, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.058.

- Abderrazak Amna; Couchie Dominique; Mahmood Dler Faieeq Darweesh; Elhage Rima; Vindis Cécile; Laffargue Muriel; Matéo Véronique; Büchele Berthold; Ayala Monica Rubio; El Gaafary Menna; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Antiatherogenic Effects of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor Arglabin in ApoE2.Ki Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Circulation 2015, 131, 1061–1070, doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013730.

- van der Heijden Thomas; Kritikou Eva; Venema Wouter; van Duijn Janine; van Santbrink Peter J.; Slütter Bram; Foks Amanda C.; Bot Ilze; Kuiper Johan NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition by MCC950 Reduces Atherosclerotic Lesion Development in Apolipoprotein E–Deficient Mice—Brief Report. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2017, 37, 1457–1461, doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309575.

- Marín-Aguilar, F.; Castejón-Vega, B.; Alcocer-Gómez, E.; Lendines-Cordero, D.; Cooper, M.A.; de la Cruz, P.; Andújar-Pulido, E.; Pérez-Alegre, M.; Muntané, J.; Pérez-Pulido, A.J.; et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition by MCC950 in Aged Mice Improves Health via Enhanced Autophagy and PPARα Activity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, doi:10.1093/gerona/glz239.

- Luo, H.; Mu, W.-C.; Karki, R.; Chiang, H.-H.; Mohrin, M.; Shin, J.J.; Ohkubo, R.; Ito, K.; Kanneganti, T.-D.; Chen, D. Mitochondrial Stress-Initiated Aberrant Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Regulates the Functional Deterioration of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Aging. Cell Rep 2019, 26, 945-954.e4, doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.101.

- Katsyuba, E.; Mottis, A.; Zietak, M.; De Franco, F.; van der Velpen, V.; Gariani, K.; Ryu, D.; Cialabrini, L.; Matilainen, O.; Liscio, P.; et al. De novo NAD+ synthesis enhances mitochondrial function and improves health. Nature 2018, 563, 354–359, doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0645-6.