Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chalid Assaf | + 2712 word(s) | 2712 | 2021-12-30 07:14:24 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | Meta information modification | 2712 | 2022-01-06 07:22:15 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Assaf, C. Contemporary Treatment Patterns in Relapsed/Refractory CTCL. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17772 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Assaf C. Contemporary Treatment Patterns in Relapsed/Refractory CTCL. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17772. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Assaf, Chalid. "Contemporary Treatment Patterns in Relapsed/Refractory CTCL" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17772 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Assaf, C. (2022, January 05). Contemporary Treatment Patterns in Relapsed/Refractory CTCL. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17772

Assaf, Chalid. "Contemporary Treatment Patterns in Relapsed/Refractory CTCL." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

The treatment pattern of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) remains diverse and patient-tailored. A European observational study provided real-world data on the current treatments used in the management of CTCL across three lines of therapy. As a result, there was a significant level of heterogeneity in treatment types than expected by European guidelines.

CTCL

pcALCL

treatment

observational study

survival

mycosis fungoides

sezary syndrome

lymphoma

1. Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) involving T-lymphocytes of the skin, accounting for 4% of all NHLs [1]. CTCL is a debilitating hematological malignancy in the skin lymphoid tissue, for which treatment remains diverse and patient-tailored [1][2][3][4]. Multiple subtypes of CTCL exist; the two most common subtypes are mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS), which together account for 65% of all CTCL cases [1]. Over time, the reported incidence of CTCL has been steadily increasing. In Europe, the incidence of CTCL is approximately 1200 new cases per year, with a prevalence of approximately 16,000 cases [5][6]. The disease is more common among men and has a peak incidence among people between the ages of 70 and 80 years [5][7].

Treatment plans for CTCL are variable and dependent on the extent and anatomical location of skin involvement, type of skin lesions and whether the lymphoma has extracutaneous involvement [8][9][10]. With the exception of an allogeneic stem cell transplant and localized radiotherapy in unilesional MF, there are no curative therapies for this disease [11][12]. Therefore, therapy is multimodal and takes place over the course of a lifetime [12]. Systemic therapy is typically deferred until patients fail to respond to skin-directed therapies [12][13]. Therapy also depends on the subtype of CTCL [10]. Patients with primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (pcALCL) typically present with localized tumors or nodules that are treated with local radiotherapy (RT) or surgical excision [10]. Patients with early-stage MF typically start with skin-directed therapy and local RT when infiltrated plaques occur [10]. Patients refractory to local skin-directed therapy go on to receive a combination of psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) plus systemic therapy, e.g., interferon (IFN) alpha, PUVA plus retinoids, IFN-alpha plus retinoids or total-skin electron-beam irradiation (TSEB) [10]. For patients with advanced and/or refractory disease, systemic mono chemotherapy with methotrexate, gemcitabine or liposomal doxorubicin can be initiated [10].

Newer agents such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors or low-dose folate inhibitors can also be used for systemic therapy in some countries [9]. Patients with SS have systemic disease at onset and are treated with skin-directed therapy (such as PUVA or a potent topical steroid) as adjuvant therapy. Other options considered for patients with systemic SS include extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP), chlorambucil plus prednisone, methotrexate, ECP alone or in combination with IFN-alpha, retinoid, TSEB or PUVA and systemic therapies in combination with PUVA (either IFN-alpha or retinoids) [8][10][14]. Second-line therapy for SS includes alemtuzumab, gemcitabine, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, mogamulizumab, CHOP (i.e., cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), CHOP-like polychemotherapies and other multi-agent chemotherapy. Recently, CD30-targeting agents have been investigated and approved as a therapy for CTCL and may create new treatment opportunities for this disease [15][16][17].

2. Disease Stage across Lines of Therapy

At diagnosis, the proportion of patients with advanced CTCL was 39.0% for MF and SS (stage IIB–IV) compared to 32.4% for non-MF and non-SS subtypes (T3-T4). A shift towards higher stages was observed (upstaging) with increasing lines of therapy. Indeed, ISCLC/EORTC stages I, II, III and IV changed from 44.7%, 18.7%, 8.1% and 15.4% at diagnosis, to 34.1%, 26.1%, 9.8% and 17.1% at first-line treatment initiation, respectively. The observed 10.6% decrease in stage I coincided with a 10.8% increase in stages II, III and IV. Upstaging continued at the time of second-line treatment initiation. Indeed, ISCLC/EORTC stage I, II, III and IV were 26.3%, 28.8%, 13.6% and 17.8%, respectively, indicating a 7.8% decrease in stage I and a coinciding increase of 7.2% in stages II–IV. At the time of second-line treatment initiation (i.e., first R/R population), the proportion of patients with advanced stages was also higher than at diagnosis (MF/SS: 55.9% vs. 39.0%; non-MF/non-SS: 36.4% vs. 32.4%, respectively). At the time of third-line treatment initiation, too many patients had been excluded from the study population (due to patients not being treated after second R/R or treatment being unknown) to be able to interpret the changes observed.

3. Treatments by Lines of Therapy

Among the 157 included patients, 151 proceeded to second-line and 90 to third-line therapy. Six patients who were either untreated or whose treatment was unknown were excluded from the second-line population. Sixty-one patients who were untreated, had an unknown treatment or did not relapse or become refractory after second-line treatment were excluded from the third-line population. The number of patients who received systemic therapy within routine practice (with or without RT/skin-directed therapy) was 147 in the first line, 125 in the second line and 72 in the third line. The number of patients who received RT alone or local skin-directed alone was 10 in the first line, 16 in the second line and 10 in the third line. Finally, the number of patients who received a HSCT or were treated in a clinical trial was 10 in the second and 8 in the third line.

3.1. First-Line Therapy

At the initiation of first-line therapy, 51/157 (32.5%) patients developed new lesions in addition to those present at diagnosis. At that time, the majority of the study population had skin symptoms (i.e., skin symptoms present in 115 (73.2%), absent in 31 (19.7%) and unknown in 11 (7.0%)). The three most common skin symptoms were pruritus/itching in 91 (58.0%), rash in 50 (31.8%) and irritation/burning in 61 (38.9%). The most serious skin symptoms included weeping lesions in two (1.3%), ulceration in three (1.9%), tumors in three (1.9%) and other types of skin cancer in two (1.3%).

A total of 147 patients (93.6%) received systemic therapy as first-line treatment, alone in 47/147 (32.0%), with RT in 12/147 (8.2%), with local skin-directed therapy in 67/147 (45.6%) or with a combination of RT and local skin-directed therapy in 21/147 (14.3%). A total of 10 patients received RT alone or RT with skin-directed therapy. Overall, systemic therapy with local skin-directed therapy was the most common treatment in the first line.

The regimen details of the systemic therapies (excluding ECP) received by 147 patients and used by two or more patients in the first line are presented in Table 1. Systemic therapy was diverse in the first line, including chemotherapy (i.e., methotrexate, single conventional cytotoxic agent and combination of conventional cytotoxic agents) in 67 (45.6%), retinoids including bexarotene in 39 (26.5%), IFN in 31 (21.1%), ECP in 4 (2.7%), corticosteroids in 3 (2.0%) and novel agents in 3 (2.0%). Single-agent chemotherapy (excluding methotrexate) was administered to 23 (15.6%), either alone or in combination with bexarotene or prednisone. Single agents received by more than one patient included gemcitabine in eight (5.4%), chlorambucil in six (4.1%) and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in six (4.1%) (Table 1). Combination chemotherapy was received by 21 (14.3%) and was often administered along with prednisone, methylprednisolone, bexarotene or both a corticosteroid and bexarotene. In the first line, combination chemotherapies were either CHOP/CHOP-like (12.2%) or EPOCH/EPOCH-like (2%). Finally, the new agents alemtuzumab, brentuximab vedotin and bortezomib were received by one patient each, either alone or with chemotherapy. Among the 89 patients who received skin-directed therapy, PUVA phototherapy was the most common non-topical therapy and was used in 43 (48.3%) patients. Topical therapies included corticosteroids, nitrogen mustard (i.e., carmustine) and mechlorethamine. RT was most commonly electron beam, used in 22/43 (51.2%), and its extent was local in 37/43 (86.0%) and total skin (TSEBT) in 6/43 (14.0%).

Table 1. Regimens used by 2 or more patients in at least one line of therapy.

| Systemic Treatment | 1st Line (n = 157) | 2nd Line (n = 151) | 3rd Line (n = 90) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Systemic therapy, N | 147 | - | 125 | - | 72 | - |

| Bexarotene | 25 | 17.0 | 27 | 21.6 | 9 | 12.5 |

| Methotrexate | 23 | 15.6 | 18 | 14.4 | 7 | 9.7 |

| Acitretin | 13 | 8.8 | 6 | 4.8 | 3 | 4.2 |

| Gemcitabine | 8 | 5.4 | 18 | 14.4 | 5 | 6.9 |

| Chlorambucil | 6 | 4.1 | 3 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin | 6 | 4.1 | 3 | 2.4 | 2 | 2.8 |

| Doxorubicin | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 2 | 2.8 |

| CHOP/CHOP-like | 18 | 12.2 | 6 | 4.8 | 3 | 4.2 |

| EPOCH/EPOCH-like | 3 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.4 |

| IFN-α | 29 | 19.7 | 14 | 11.2 | 11 | 15.3 |

| IFN-γ | 2 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Alemtuzumab | 1 | 0.7 | 2 | 1.6 | 3 | 4.2 |

| Brentuximab vedotin | 1 | 0.7 | 8 | 6.4 | 7 | 9.7 |

| Bortezomib | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Total number used in ≥2 patients | 136 | 92.5 | 106 | 84.8 | 55 | 76.4 |

Outcomes of First-Line Therapy: Clinical Response, Skin Symptoms and Time to First R/R

Following first-line therapy, 128 patients had a known global response, including a complete response in 22 (14.0%), a partial response in 46 (29.3%), a stable disease in 20 (12.7%) and progressive disease in 40 (25.5%). Among the 29 patients whose global response was unknown, 17 had a known skin response (i.e., three (1.9%) complete, eight (5.1%) partial, five (3.2%) stable and one (0.6%) progression). ORR based on global and skin response was 79/157 (50.3%). Overall, 41/157 (26.1%) experienced disease progression. These estimates are conservative due to 12 patients with an unknown response being included in the denominator.

After first-line treatment, skin symptoms were present in 101 (64.3%), absent in 35 (22.3%) and unknown in 21 (13.4%). The three most common skin symptoms were again pruritus/itching in 77 (49.0%), rash in 36 (22.9%) and irritation/burning in 56 (35.7%), but, notably, the prevalence was lower compared to when first-line treatment was initiated. The most serious skin symptoms observed included weeping lesions in two (1.3%), ulceration in two (1.3%), tumors in three (1.9%) and other types of skin cancer in three (1.9%).

All patients who received a first-line therapy eventually relapsed or became refractory, as per the inclusion criteria. The median time to first R/R was 10.3 months (range: 0.3–255.1).

3.2. Second-Line Therapy

Among the 151 patients who initiated second-line therapy, 91 (60.3%) developed new lesions at the time of treatment initiation. The median age was 60.0 years (range: 19.0–98.0). A total of 125 patients (82.8%) received systemic therapy as second-line treatment, alone in 50/125 (40.0%), with RT (with or without skin-directed therapy) in 30/125 (24.0%) or with local skin-directed therapy in 45/125 (36.0%). A total of 16 patients received RT alone, skin-directed alone or RT with skin-directed therapy. Overall, systemic therapy alone was the most common therapy in the second line.

The details of the systemic therapies received by 125 patients in the second line are presented in Table 1. Systemic therapies included chemotherapy in 59 (47.2%), retinoids (including bexarotene) in 33 in (26.4%), IFN in 14 (11.2%), novel agents in 10 (8.0%), ECP in 5 (4.0%), corticosteroids in 2 (1.6%) and HDAC-inhibitors in 2 (1.6%). An uptake in the use of novel agents was observed in the second line. Novel agents consisted of alemtuzumab in two (1.6%) and brentuximab vedotin in eight (6.4%). Single-agent chemotherapies were similar to those encountered in the first line, with a predominance of gemcitabine, which was used in 18 patients (Table 1). As in the first line, these single agents were often used along with prednisone, acitretin, IFN, methotrexate and bexarotene. In contrast to the first line, there was a multitude of different combination chemotherapies in the second line. Combination chemotherapies included CHOP in 4.8% of patients. The remainder received a mosaic of combination chemotherapies, including cyclophosphamide-based combinations, gemcitabine-based regimens, cisplatin–cytarabine, thiotepa-busulfan and bendamustine-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. These regimens were again often used with bexarotene, IFN, methotrexate, prednisone, dexamethasone or methylprednisolone. The use of brentuximab vedotin was more prevalent in the second line compared to the first line (8 versus 1, respectively), most often with another chemotherapy agent. PUVA phototherapy was the most common therapy besides topical therapies. Similar to observations in the first line, topical treatment consisted of steroids, carmustine and mechlorethamine. RT was most commonly electron beam, as opposed to X-ray seen in the first line. RT was local in 72.7% and total in 20.5%.

Outcomes of Second-Line Therapy: Clinical Response, Skin Symptoms, Toxicity and Time to R/R

Following second-line therapy, clinical response was evaluated for 141 patients who received systemic therapy (125), RT (14) or local skin-directed therapy (2). Global response was known in 108 patients and included a complete response in 20 (14.2%), a partial response in 41 (29.1%), stable disease in 18 (12.8%) and progressive disease in 29 (20.6%). In the 33 patients whose global response was unknown, local skin response was known in 18. ORR based on global and skin response was 51.1%. Overall, at least 23.4% of patients experienced disease progression based on known responses recorded. Based on data from 119 patients, the median time to second R/R was 11.2 months (range: 0–174.6). In those patients (n = 61) who received bexarotene or methotrexate (with or without other therapies), ORR based on global and skin response was 47.5%. As many as 31.2% of these patients experienced progression.

Among the 141 patients, skin symptoms were present in 67 (47.5%) and absent in 52 (36.9%). The three most common symptoms were again pruritus/itching in 52 (36.9%), irritation/burning in 33 (23.4%) and rash in 31 (22.0%). No weeping lesions were observed after second-line therapy. Ulceration, tumors and other types of skin cancers were observed in one patient each.

Among the 141 patients who received systemic therapy, RT or skin-directed therapy in the second line, non-skin-related adverse events were reported to be present in 45 (31.9%) and absent in 71 (50.4%). Hematologic adverse events included febrile neutropenia (14.9%), anemia (7.8%), leukopenia (3.5%), neutropenia (2.8%) and thrombocytopenia (2.8%). The most common non-hematologic adverse events (present in >10 patients) included alopecia (18.4%), fatigue/asthenia (12.1%) and anorexia (7.1%). Serious adverse events included sepsis and pulmonary embolism, which were experienced by one patient each.

3.3. Third-Line Therapy

Among the 90 patients who initiated third-line therapy, 53 (58.9%) developed new lesions, indicating a worsening of disease in the majority of patients. A total of 72 patients received systemic therapy in the third line, alone in 34/72 (47.2%), with RT (with or without skin-directed therapy) in 16/72 (22.2%) or with skin-directed therapy alone in 22/72 (30.6%). A total of 10 patients received RT alone, RT with skin-directed therapy or skin-directed therapy alone.

Systemic therapy agents received by 72 patients in the third line are presented in Table 1. Systemic therapies included chemotherapy in 31 (43.1%), retinoids (including bexarotene) in 13 (18.1%), IFN in 11 (15.3%) and a novel agent in 11 (15.3%). As in the second line, there was a multitude of combination chemotherapies, including CHOP, EPOCH, cyclophosphamide-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens and vincristine–vinblastine–mitoxantrone. Dexamethasone, bexarotene, prednisone and methylprednisolone were often administered with combination chemotherapy. Again, as in previous lines, PUVA was the most common skin-directed therapy besides topical therapies. RT was local in 68.0% and total in 32.0% of patients.

Outcomes of Third-Line Therapy: Clinical Response, Skin Symptoms, Toxicity and Time to R/R

Following third-line therapy, clinical response was evaluated in 82 patients who received systemic therapy (72), RT (9) or local skin-directed therapy (1). Global response was known in 60 patients and included a complete response in 12 (14.6%), a partial response in 20 (24.4%), stable disease in 11 (13.4%) and progressive disease in 17 (20.7%). In the 22 patients whose global response was unknown, local skin response was known in 11. ORR based on global and skin response was 45.1%. Overall, at least 20 (24.4%) experienced progressive disease. Based on 59 patients, the median time to a third R/R was 7.9 months (range 0.0–39.0).

Among the 82 patients, skin symptoms were present in 33 (40.2%), pruritus/itching in 19 (23.2%), irritation/burning in 15 (18.3%) and rash in 11 (13.4%), being the three most common skin symptoms.

Among the 82 patients who received systemic therapy, RT or skin-directed therapy in the third line, non-skin-related adverse events were present in 18 (22.0%) and absent in 48 (58.5%). The most common hematologic adverse events included febrile neutropenia (12.2%), anemia (6.1%) and leukopenia (4.9%). The most common non-hematologic adverse event (present in > 10 patients) was alopecia (15.9%). Serious adverse events included sepsis in two (2.4%) and both pulmonary embolism and renal failure in one patient.

4. Treatment Pattern Focusing on Systemic Therapies

The broad treatment pattern (including no treatment) across the three lines of therapy is summarized in Table 2. The number of patients treated with chemotherapy, retinoids and IFN decreased with increasing lines of therapy, while the number of untreated patients increased with increasing lines of therapy. The number of patient treated with novel agents and HDAC inhibitors trended towards a slight increase with increasing lines of therapy.

Table 2. Treatment pattern across the 3 lines of therapy.

| Treatment Type | 1st Line | 2nd Line | 3rd Line | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total, N | 157 | 100 | 157 | 100 | 157 | 100 |

| Chemotherapy † | 67 | 42.7 | 59 | 37.6 | 31 | 19.7 |

| Retinoids ‡ | 39 | 24.8 | 33 | 21.0 | 13 | 8.3 |

| IFN and corticosteroids | 34 | 21.7 | 16 | 10.2 | 11 | 7.0 |

| ECP | 4 | 2.5 | 5 | 3.2 | 4 | 2.5 |

| HDAC inhibitors or novel agents | 3 | 1.9 | 12 | 7.6 | 13 | 8.3 |

| RT alone and/or skin-directed therapy alone | 10 | 6.4 | 16 | 10.2 | 10 | 6.4 |

| HSCT or clinical trial * | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 6.4 | 8 | 5.1 |

| No treatment | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 3.8 | 67 | 42.7 |

5. Survival Outcomes

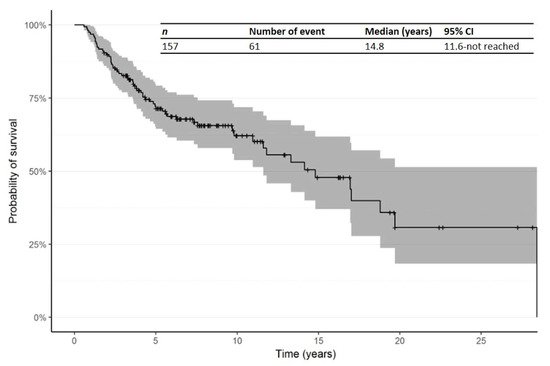

At the date of last follow-up, 61 (38.9%) had died, 93 (59.2%) were alive and 3 (1.9%) had unknown survival status. The median age at time of final status was 67.0 years (range: 25.0–85.0). The median duration of follow-up since time of first R/R was 3.2 years (Range: 0.0–26.0 years; IQR: 1.8–5.5 years). The main causes of death were CTCL (52.5%), CTCL complications or toxicity (18.0%), other causes (19.7%) and unknown (9.8%). The Kaplan–Meier curve for OS from time of diagnosis is shown in Figure 2. The median OS from time of diagnosis was 14.8 years (95% CI: 11.6—not reached).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival (OS) from time of diagnosis. Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; OS: overall survival.

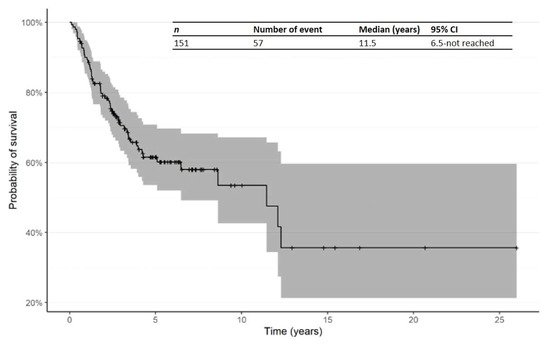

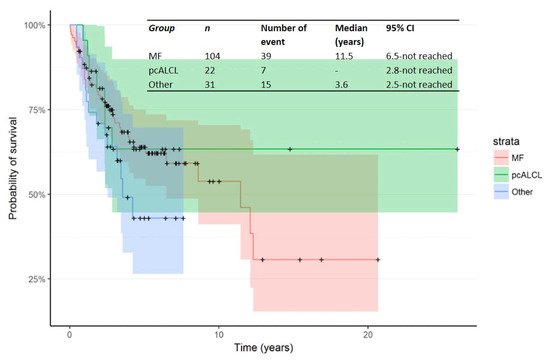

The Kaplan–Meier curve for OS from time of first R/R in patients treated in the second line is shown in Figure 3. The median OS from time of first R/R was 11.5 years (95% CI: 6.5—not reached). In addition, Kaplan–Meier curves for OS from time of R/R1 by primary subtype for Mf, pcALCL and others are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier curve for OS from time of first relapsed/refractory in patients receiving second-line therapy. Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; OS: overall survival; R/R: relapsed/refractory.

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier curve for OS from time of R/R1 by primary subtype.

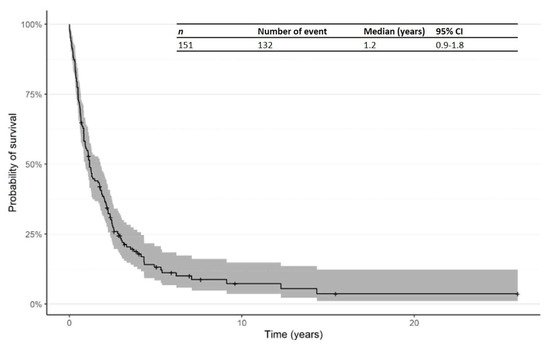

The Kaplan–Meier curve for PFS from time of first R/R in patients treated in the second line is shown in Figure 5. The median PFS from time of first R/R was 1.2 years (95% CI: 0.9–1.8).

Figure 5. Kaplan–Meier curve for progression-free survival (PFS) from time of first R/R in patients receiving second-line therapy. Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; PFS: progression-free survival; R/R: relapsed/refractory.

References

- Zinzani, P.L.; Bonthapally, V.; Huebner, D.; Lutes, R.; Chi, A.; Pileri, S. Panoptic clinical review of the current and future treatment of relapsed/refractory T-cell lymphomas: Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 99, 228–240.

- Olsen, E.A. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Staging of Cutaneous Lymphoma. Dermatol. Clin. 2015, 33, 643–654.

- Photiou, L.; van der Weyden, C.; McCormack, C.; Miles Prince, H. Systemic Treatment Options for Advanced-Stage Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 20, 32.

- Willemze, R.; Jaffe, E.S.; Burg, G.; Cerroni, L.; Berti, E.; Swerdlow, S.H.; Ralfkiaer, E.; Chimenti, S.; Diaz-Perez, J.L.; Duncan, L.M.; et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood 2005, 105, 3768–3785.

- European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Mycosis Fungoides. 2016. Available online: http://www.efpia.eu/diseases/15/59/Mycosis-Fungoides (accessed on 21 December 2016).

- Dobos, G.; Pohrt, A.; Ram-Wolff, C.; Lebbé, C.; Bouaziz, J.D.; Battistella, M.; Bagot, M.; de Masson, A. Epidemiology of Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 16,953 Patients. Cancers 2020, 12, 2921.

- Bradford, P.T.; Devesa, S.S.; Anderson, W.F.; Toro, J.R. Cutaneous lymphoma incidence patterns in the United States: A population-based study of 3884 cases. Blood 2009, 113, 5064–5073.

- Trautinger, F.; Eder, J.; Assaf, C.; Bagot, M.; Cozzio, A.; Dummer, R.; Gniadecki, R.; Klemke, C.D.; Ortiz-Romero, P.L.; Papadavid, E.; et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome—Update 2017. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 77, 57–74.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Primary Cutaneous Lymphomas. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1491 (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Willemze, R.; Hodak, E.; Zinzani, P.L.; Specht, L.; Ladetto, M.; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, vi149–vi154.

- Schlaak, M.; Pickenhain, J.; Theurich, S.; Skoetz, N.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; Kurschat, P. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation versus conventional therapy for advanced primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, 1, CD008908.

- Lansigan, F.; Foss, F.M. Current and emerging treatment strategies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Drugs 2010, 70, 273–286.

- Lymphoma Research Foundation. Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (CTCL). 2014. Available online: http://www.lymphoma.org/site/pp.asp?c=bkLTKaOQLmK8E&b=6300151 (accessed on 21 December 2016).

- Willemze, R.; Hodak, E.; Zinzani, P.L.; Specht, L.; Ladetto, M.; on behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Committee. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, iv30–iv40.

- Prince, H.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Horwitz, S.M.; Dummer, R.; Scarisbrick, J.; Quaglino, P.; Zinzani, P.L.; Wolter, P.; Sanches, J.A.; Ortiz-Romero, P.L.; et al. Brentuximab vedotin or physician’s choice in CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (ALCANZA): An international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 555–566.

- Bagot, M. New Targeted Treatments for Cutaneous T-cell Lymphomas. Indian J. Dermatol. 2017, 62, 142–145.

- Kim, Y.H.; Bagot, M.; Pinter-Brown, L.; Rook, A.H.; Porcu, P.; Horwitz, S.M.; Whittaker, S.; Tokura, Y.; Vermeer, M.; Zinzani, P.L.; et al. Mogamulizumab versus vorinostat in previously treated cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (MAVORIC): An international, open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1192–1204.

More

Information

Subjects:

Dermatology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

775

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No