Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dr. Köves Alexandra | + 2598 word(s) | 2598 | 2021-12-17 05:09:27 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 2598 | 2022-01-04 11:10:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Alexandra, D.K. Cuvée Organizations. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17728 (accessed on 13 January 2026).

Alexandra DK. Cuvée Organizations. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17728. Accessed January 13, 2026.

Alexandra, Dr. Köves. "Cuvée Organizations" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17728 (accessed January 13, 2026).

Alexandra, D.K. (2022, January 04). Cuvée Organizations. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17728

Alexandra, Dr. Köves. "Cuvée Organizations." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

The concept of the cuvée organization emerged from participatory backcasting, a normative scenario-building exercise conducted with a sustainability expert panel. In this co-creative process, the panel capitalized on the metaphor of cuvée wine and winemaking, which provided the cognitive means to chart the unknown. The emerged concept of the cuvée organization stands for a business archetype which is designed to serve a prosocial cause, subordinating activities and structural features accordingly.

sustainable business

discounting

decision making

cuvée organization

1. Meta-Level Conceptualization of the Cuvée Organization

What would it take to earn a social license to operate a business organization in 2050? To address the question, the expert participants have formulated a vision for 2050 considering wider socioeconomic and narrower organizational aspects. The following is an excerpt from the backcasting vision:

“In 2050, the economy is the subsystem of society, that is the subsystem of the natural environment. They are fully embedded in each other and interact directly and dynamically. The purpose of economic organizations is to serve human communities and nature, and to solve ecological and social Causes (Cause-driven organizations). Profit maximization is not an end in itself. However, profit exists but it is an indicator of value creation in a specific cause. As a result of convergence between the civil and corporate sectors, Cuvée organizations are operating. Economic organizations are organized into ecosystem-like networks. The nodes of the networks are built around core competencies that are needed to address some of the Causes at the heart of economic organizations. The relationship between the organizations is based on coopetition, an expression reflecting open and unrestricted sharing of knowledge and experience. At the same time, a healthy and constructive competition for development exists and is accepted in the economy. There are self-regulating mechanisms in the network that prevent strong power positions from forming. Decisions are made in a decentralized manner within the network and within economic organizations, at the level closest to the point where the given problem occur. The responsibility of economic organizations extends along the entire supply chain, and all those directly and indirectly involved in the supply chain are all considered stakeholders of the economic organization. The economic organization is the arena for democracy both for external and internal stakeholders. The communities concerned can participate meaningfully in the strategic decision-making and planning processes and have the necessary authority to do so. The characteristics of the product make it clear what social and natural impacts occur throughout its life cycle. The operation of the economic organization and the production process of the products are completely transparent. This transparency acts as a self-regulating mechanism in the economy. The brand of an economic organization is basically the embodiment of the Cause that it seeks to resolve with its core business.”

The single most influential change factor compared to contemporary dominant ways to do business appears to be a meta-level turn: leaving behind profit maximization and instead organizing around cause drivenness. The meta-level is the realm of higher order principles, values and rules which are reflected in the micro-level. The micro-level is shaped by the macro and consists of actions and decisions (relying loosely on Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development framework [1]). Abandoning the supremacy of profit maximizing for the sake of serving a prosocial cause has far-reaching consequences regarding multiple fundamental characteristics of a business organization.

Table 1 summarizes the main perspectives that change with the emergence of the cuvée organizations.

Table 1. Meta level comparison of the business approach to be replaced by the cuvée organization.

| Perspective | Approach to Be Replaced | Cuvée Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Activity focus | manufacturing/service-provision | solution |

| Motivation | profit-maximization | cause-drivenness |

| Brand | image driven by marketing | the cause |

| Profit | ultimate strategic goal | indicator of success in advancing the cause |

| Systems view | atomistic, self-interested | network-based, embedded |

| Relation to other economic Actors | competition | coopetition |

| Power (market) | globally concentrated | decentralised, relocalised |

| Knowledge | protected by patents | open-source |

| Approach | shareholder view | stakeholder view |

| Relation to staff | employee | partner |

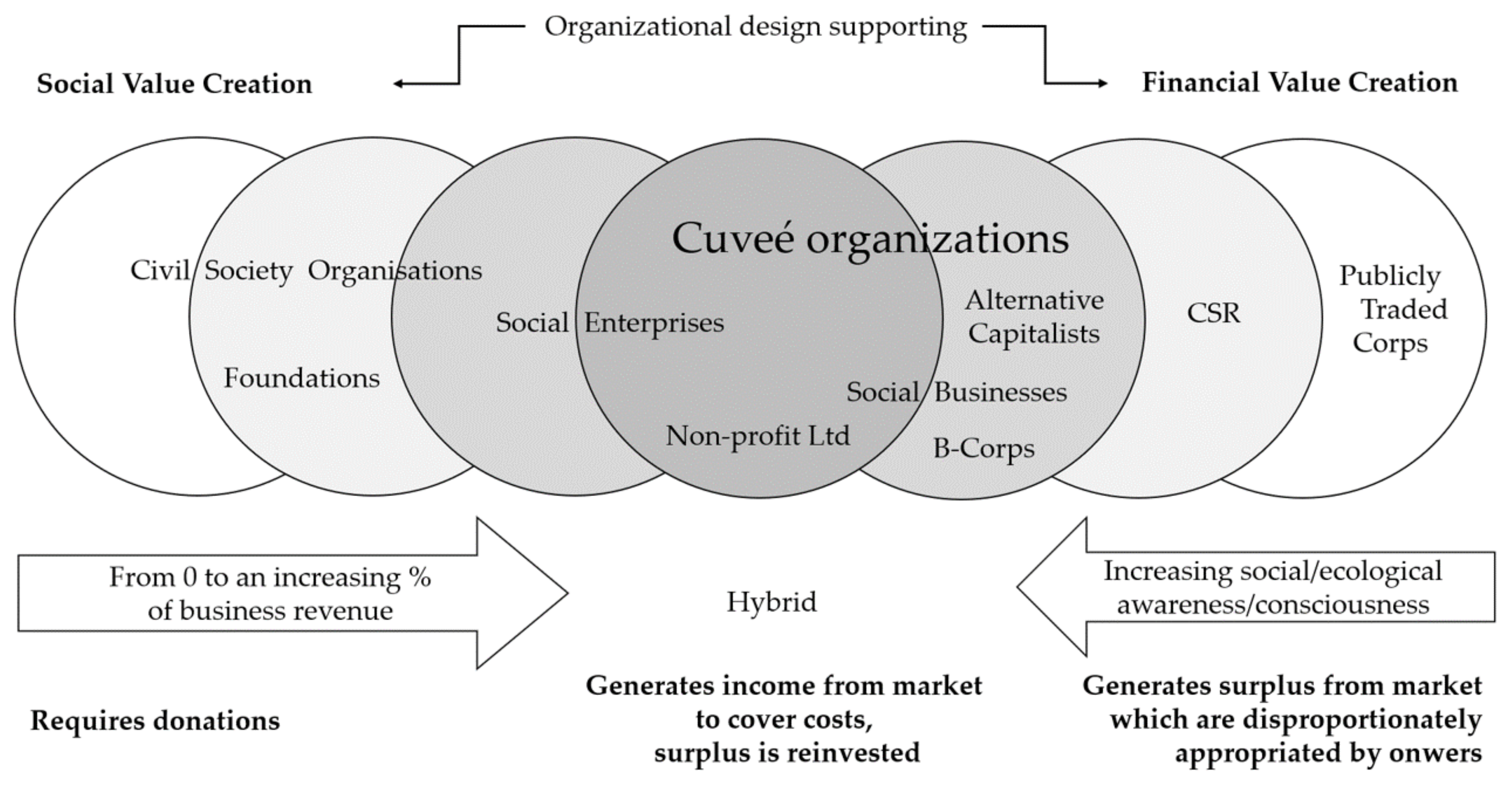

Figure 1 also illustrates that shifting from the realm of social towards financial value creation, the organizational structure and bylaws allow for a higher degree of personal wealth appropriation. A crucial organizational setup therefore is how organizations—capable of generating financial revenues—can channel surplus resources towards the service of the prosocial cause, instead of transforming them into private income or wealth.

Figure 1. Organizations on the cause-profit coordinate system (inspired by Ryder–Vogeley [2] and Wilson and Post [3]).

2. Micro-Level Application of the Concept of the Cuvée Organization: The Example of Fighting Discounting for the Sake of Sustainable Decision Making

The complexity of the cuvée organization does not allow us to cover all aspects of its hypothetical operations. Therefore, it is necessary to zoom into a micro-level application where we can focus on one specific perspective of its functioning to test its suitability to sustainability. Hence, we now turn our attention to behavioral economics when introducing the hypothetical organizational form of the cuvée organization as we agree with scholars who say that it is no longer the lack of knowledge that stops us from acting consciously towards our social and ecological environment but certain attributes of human behavior that makes this endeavor difficult [4][5]. Behavioral economics covers a vast field of psychological phenomena like diverse types of heuristics and biases, affect, and emotions. For the sake of our argumentation in this paper, to investigate how the cuvée organization might differ from currently known mainstream economic actors in their decision making, it is sufficient for us to focus on one dimension of behavioral economics. Our choice fell on the phenomena of discounting because it poses a serious threat to tackling sustainability challenges and currently constitutes an inherent part of the business environment and acts as a serious barrier to change. After a short introduction to the relationship of discounting and sustainability issues, we will introduce those proposed traits of the cuvée organization that may enable it to counterbalance the innate emergence of discounting in their decision-making processes. This should serve as an example of a micro-level application of the concept of cuvée organization.

However, as we venture into the domains of behavioral decision making, it is important to make our stance explicit with regard to the conceptual choices we make in this paper. When it comes to our interpretation of behavioral decision making, our conceptual choice lies with ecological rationality. Ecological rationality supposes that behaviors contradicting the axioms of rationality may still result in successful and accurate decisions. Thus, heuristics and biases—understood as systematic violations of the rational choice theory—should not necessarily have a negative connotation. The rationality of behavior is contextualized; it is contingent on the circumstances of the decision, or as Herbert Simon suggests, on the “structure of task environments” [6] (p. 7). In Simon’s pair of scissors analogy, the two blades of cognition—the computational capabilities of the individual—and the context both play a role. The ecologically rational choice is a “match between mind and environment” [7] (p. xix), and this match can be served well with fast and frugal heuristics requiring less time, information, and computation without compromising accuracy.

2.1. Discounting and Sustainability

For centuries—mainly since the Enlightenment—economic thoughts revolved around rational choice in decision making. It was only around the 1970s when psychologists like Herbert Simon, Amos Tversky, and Daniel Kahneman managed to hit a hole in this canon. Their work gave rise to behavioral economics, a field that investigates human behavior beyond rationality principles when making decisions in the economic sphere [8][9]. As parallel development, it was also in the 1970s when economists like Herman Daly, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, or Kenneth Boulding started questioning another dogma of economic thought, namely the disjunction of the economy from its environment, and they promoted the embeddedness of the economy in the social and the ecological environment. Their work gave rise to ecological economics striving to find a way for the economy to stay within planetary boundaries for the sake of strong sustainability [10]. In current scientific discourses, these two fields often meet up in research that combines the psychological dimensions of behavioral economics and sustainability. This is where limits to rational behavior meet the limits to growth. The topic of discounting in a perfect example.

Although institutionalized discounting in economics and discounting in the psychological realm are strongly related, a distinction must be made. Discounting in economics is an everyday practice justified mainly by marginal opportunity cost of capital and is often criticized by those concerned about sustainability issues because few natural resources can compete with the marginal opportunity cost of capital, and hence profit always reigns over resources [11]. Many argue that the discounting of consumption utility or access to resources is wrong both morally and practically, not only in terms of intergenerational justice but also for aggravating current problems [12][13]. Discounting in behavioral economics—sometimes referred to as judgmental discounting—is the phenomenon whereby humans undervalue the risk of an occurrence when it happens in distant dimensions both in time and space [14]. The different dimensions of discounting are uncertainty, temporal, spatial and social distancing with uncertainty closely related to the time dimension and spatial discounting with social distancing. These dimensions influence each other and are similarly influenced by manipulations. While they may not occur simultaneously in all decision-making processes, the difficulty with sustainability issues lies exactly with the fact that all of them are present at the same time. However, discounting may appear differently when it is seen in terms of losses or in terms of ethical concerns, the latter attracting less discounting [15].

Discounting has a lot to do with psychological distancing both in terms of time and space. Research shows that taking environmental impacts into consideration that happen in the future, 30–40 years from now, are discounted the same way as if they happened outside of one’s own country [14]. At the same time, sustainability is a wicked problem that has long-term impacts: we borrow resources from future generations and due to the complex nature of ecological degradation, and the consequences of our decisions may only impact humans and nonhumans geographically distant from us. Hence, costs and responsibilities of an action that follow a decision in the economic sphere to produce or consume may not rest with those who benefit from that production and consumption. However, the emphasis is on perceived psychological distance. Pro-environmental action is less likely to take place when the decision maker perceives that this individual action may only have an influence on people in the distant future or in faraway lands. The reasons behind temporal discounting include the lack of empathy for non-existent fellow human beings, the lack of certainty regarding the future and the inability to delay gratification. Spatial discounting, on the other hand, can be traced back to lesser emotional burdens of seeing a person suffer who is not in our close vicinity, dampening our moral intuition. [14]. Loewenstein et al. [16] argue that when assessing risks while taking decisions, our feelings also deeply impact our judgments. Anticipated outcomes (including anticipated feelings) together with subjective probabilities and other factors such as immediacy or mood have a direct effect on both our feelings and cognitive evaluation that leads to our behavior and final outcomes (including feelings). Therefore, affect has a significant influence on the way we take our decisions. Effects, however, are highly sensitive to proximities in time [16].

2.2. The Cuvée Organization and Discounting

Any organization aiming for sustainability has the significant challenge of solving current challenges while maintaining a long-term perspective and aiming for resilience both internally and in their environment. When examining firms with contractual relationship between the top management and the shareholders and comparing them to family-owned businesses, Sanjay and Pramodita Sharma [17] found that ownership is an important aspect of patience in return on investments. Even though both types of organizations’ strategic decisions are based on the owners’ goals and perspectives, when relational ownership and management apply, these decisions have longer time horizons. When creating value for current stakeholders, it is important to balance them out for values of future stakeholders even if these may change in the meantime. However, this often requires long-term investments called patient capital [17]. While patient capital can also be used for malign as well as benign purposes, in our case its sheer existence is crucial in running a cuvée organization whose decision making is supposed to be long-term. Patient capital comes from investors who for various reasons are willing to invest in the long-term, often with the intention to protect certain stakeholders’ interests or secure ownership over longer periods of time. The literature on patient capital [18][19][20] focuses on financial returns on investments in the long-term, the participants in the backcasting research intuitively focused on the role of ownership and investor responsibility. Many backcasting interventions that lead to the rise of a cuvée organization deal with these two perspectives. The resulting systems map shows that participants presumed that a higher level of investor responsibility would decrease the “rate of money-generating function of money” as they called it and hence lead to the strengthening of the cause-driven approaches necessary for the penetration of cuvée organizations in the economic sphere. Urging capital to look for high socioecological return instead of high, short-term financial return on investments was deemed a prerequisite for the rise of cuvée organizations. Even though ownership was discussed as a separate issue, in the patient capital literature the two concepts interrelate. In the backcasting research, employee ownership was seen as a tool to enhance participation in strategic decision making and the representation of diverse stakeholder interests. Through these correlations, however, this proves to be also a tool to fight short-termism and discounting.

3. Conclusions

Herein aimed to inspire the ongoing scientific discourse on the role and responsibility of business organizations in a sustainability transition with a thought-provoking hypothetical concept coming from a backcasting research conducted with an expert panel. By introducing the normative concept of cuvée organization stemming from our qualitative research, we aspired to broaden scientific understanding on how the meta-characteristics of economic organizations such as their motivation, worldview, systems view, relationship to other organizations, society as a whole, their employees and other stakeholders lead to sustainability. Testing this concept to sustainability in general would have been too broad to handle, hence we used one particular perspective of sustainable decision making, namely fighting discounting as a micro-level application of these meta-characteristics. In addition, we believe that the winemaking metaphor is of great help in comprehending the details of the necessary changes in the behavior of economic actors when seeking sustainability.

Cuvée organizations are economic actors that act as strongly embedded nodes in not just economic but also social and ecological networks with a purpose to serve a particular cause important to the whole of that network. This worldview of embeddedness, relatedness, and cause drivenness puts a natural limit to the atomistic, self-centered view of profit maximization and induces coopetition instead of competition when working towards a cause. When applying these meta-characteristics to a specific area, namely fighting discounting in a process of sustainable decision making, our findings show that even without a detailed focus on counterbalancing discounting, participants intuitively based their understanding of the ideal future organization on traits that are supposed to challenge our affinity to discount. These include, for example, decentralized decision making with the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders; extensive use of employee ownership; coopetition and networking; open-source knowledge sharing; and intensive trust building through transparency. Testing the meta-characteristics of the cuvée organization on a micro-level application showed how even in just hypothetical settings, these characteristics matter in everyday decision making that serves sustainability.

References

- Ostrom, E. Institutional Analysis and Development: Elements of the Framework in Historical Perspective. Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems, II; Indiana University: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2010.

- Ryder, P.; Vogeley, J. Telling the impact investment story through digital media: An Indonesian case study. Commun. Res. Pract. 2018, 4, 375–395.

- Wilson, F.; Post, J.E. Business models for people, planet (&profits): Exploring the phenomena of social business, a market-based approach to social value creation. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 715–737.

- Gifford, R. The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302.

- Fischer, J.; Dyball, R.; Fazey, I.; Gross, C.; Dovers, C.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Brulle, R.J.; Christensen, C.; Borden, R.J. Human Behavior and Sustainability. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 153–160.

- Simon, H. Invariants of human behaviour. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1990, 41, 1–19.

- Gigerenzer, G. Heuristics: The foundations of Adaptive Behavior; Hertwig, R., Pachur, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011.

- Earl, P. Behavioural Economics; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 1990.

- Brekke, K.A.; Johansson-Stenman, O. The Behavioural Economics of Climate Change. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2008, 24, 280–297.

- Ropke, I. The Early History of Modern Ecological Economics. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 50, 293–314.

- Voinov, A.; Farley, J. Reconciling Sustainability, Systems Theory and Discounting. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 104–113.

- Hampicke, U. Climate Change Economics and Discounted Utilitarianism. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 45–52.

- Rendall, M. Climate Change and the Threat of Disaster: The Moral Case for Taking out Insurance at Our Grandchildren’s Expense. Political Stud. 2011, 59, 884–899.

- Sparkman, G.; Lee, N.R.; Macdonald, B.N.J. Discounting Environmental Policy: The Effects of Psychological Distance over Time and Space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101529.

- Gattig, A.; Hendrickx, L. Judgmental Discounting and Environmental Risk Perception: Dimensional Similarities, Domain Differences, and Implications for Sustainability. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 21–39.

- Loewenstein, G.F.; Hsee, C.K.; Weber, E.U.; Welch, N. Risk as Feelings. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 267–286.

- Sharma, S.; Sharpa, P. Patient Capital; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019.

- Deeg, R.; Hardie, I. What Is Patient Capital and Who Supplies It? Socio-Econ. Rev. 2016, 14, 627–645.

- Deeg, R.; Hardie, I.; Maxfield, S. What Is Patient Capital, and Where Does It Exist? Socio-Econ. Rev. 14 2016, 4, 615–625.

- Knafo, S.; Dutta, S.J. Patient Capital in the Age of Financialized Managerialism. Socio-Econ. Rev. 14 2016, 4, 771–788.

More

Information

Subjects:

Management

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

605

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

04 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No