| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yonas Bekele | + 2760 word(s) | 2760 | 2021-12-21 08:55:51 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 2760 | 2021-12-31 02:48:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

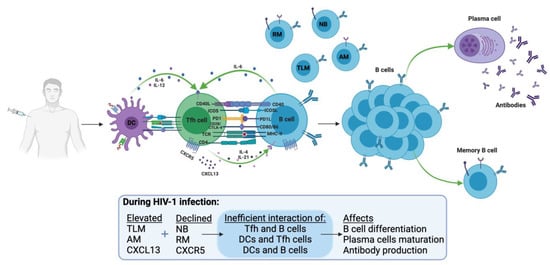

Disease progression and liver-related complications are more common in HIV-1/HBV co-infected than HBV mono-infected individuals. Response to HBV vaccine is suboptimal in HIV-1-infected individuals. Several factors affect HBV vaccine response during HIV-1 infection including CD4+ T cell counts, B cell response, vaccine formulation, schedules, and timing of antiretroviral therapy (ART). Thus, regular follow-up for antibody titer and a booster dose is warranted to prevent HBV transmission in HIV-1 infected people.

1. Introduction

2. HBV Infection in HIV-1 Infected Individuals

3. The Impact of Immunological and Virological Parameters on Response to HBV Vaccine in HIV-1 Infected Individuals

The most common schedule for HBV vaccination is three doses of the vaccine at 0–1–6 months; however, an accelerated vaccination schedule at 0–4–8 weeks is also recommended for high-risk individuals to increase vaccine compliance and elicit higher antibody responses. In the latter schedule, a fourth dose was recommended to slow down the decline of anti-HBs antibodies and for long-term protection. Several studies in different settings showed a decline in the anti-HBs antibodies a few or several years after vaccination, depending on the vaccination strategies and other factors. Lower response to HBV vaccine and short duration of protection were reported in HIV-1-infected individuals.

In support of the role of CD4+ T cell count, a study conducted in Rwanda reported an association between HBV vaccine response in HIV-1-infected children and adolescents with CD4+ T cell counts higher than 350 cells/μL and a viral load below 40 RNA copies/mL [25]. An association between CD4+ T cell counts and response to HBV vaccine was also observed in adults with AIDS receiving an efavirenz-based ART regiment [26].

Regarding a gender effect, the likelihood of responding to the HBV vaccine was higher in adult HIV-1-infected women, compared to men, when these patients presented with CD4+ T cell counts >350 cells/μL [27].

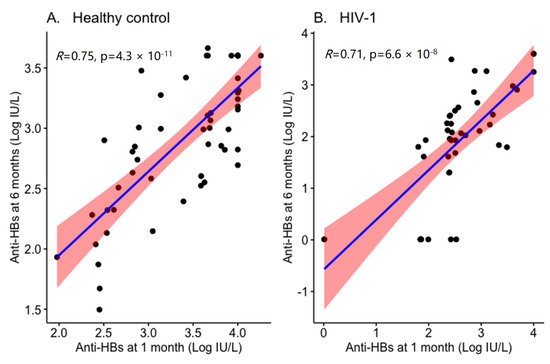

Initial response to the vaccine was also predictive of sustained vaccine responses. Lopes and colleagues [28] reported that in HIV-1 infected individuals the persistence of protective anti-HBs antibody titers relates to the response levels at primary vaccination; in addition, in patients with a pronounced (>1000 IU/I) vaccine response at primary vaccination, the meantime loss of effective anti-HBs titer was 4.4 years [28]. Similarly, we have also found a direct correlation between anti-HBs antibody titer at 1 month and 6 months from the last dose of HBV vaccination in Ethiopian children (Figure 1). The immunological correlates presented by Lopes et al., (2013) remain somehow unclear, as a high CD4+ T cell count paradoxically was inversely correlated to strong response at primary vaccination.

4. Booster or the Additional Dose of HBV Vaccine for HIV-1 Infected Individuals

Long-term protection and anamnestic response were reported after childhood HBV vaccination in immunocompetent individuals (Table 1). Protective anti-HBs titers were measured in only 37% of healthy participants (n = 300) attending the health center of Rafsanjan (Kerman province, southeast of Iran) 20 years from primary vaccination [37]; a single booster was administered to participants who had less than 10 IU/L of anti-HBs and the majority (>97%) responded to re-vaccination, suggesting the presence of an anamnestic response in previously vaccinated immunocompetent individuals [37]. The study shows that in immunocompetent individuals, loss of protective antibody does not necessarily imply the absence of immunity against HBV and contributes to the discussion on whether a booster dose of HBV vaccine should be administered to immunocompetent individuals [38]. Other studies also confirm that administration of booster dose(s) may not be necessary for these individuals and that childhood HB vaccination is sufficient to prevent HBV infection [20][39][40][41][42]. However, further studies should be conducted to prevent breakthrough infection of vaccine escape mutants in immunocompetent individuals living in the hyperendemic regions.

| No | Schedule at Birth | Duration of Follow-Ups (Years) | Anamnestic Response and Timing | Response Rate for Non-Responder upon the 2nd Dose | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2, 4 & 6 months age | 9 months to 16 years | Single-dose 10 μg. At 1 month: 95% for pre-booster detectable anti-HBs. 85% for undetectable pre-booster level. |

3 doses; 92.3% | Egypt | [39] |

| 2 | 0, 1, and 6 months | 5–15 years | 0–1–6 months, 10 μg. For < 10 mIU/mL *: 95.65% at 1 month. For > 10 mIU/mL *: 100% at 1 month. |

NA | China | [43] |

| 3 | 3 doses, at birth or 12 years | 17.2 and 19.3 years after the last vaccination | Single-dose; at 1 month 88.8%. | Another dose, 100% | Italy | [44] |

| 4 | 3 or more doses, at birth or young age | Single-dose; at 1 month 89.9%. | 2 more doses; 96.2% | Italy | [45] | |

| 5 | 4 doses; First 2 years of life | Aged 14–15 years | Single-dose 10 µg. At 1 month. For < 6.2 mIU/mL *: 82.9%. For > 6.2–<10 mIU/mL *: 100%. For > 10 mIU/mL *: 98.6%. |

NA | Germany | [46] |

| 6 | 3 doses, at birth or during adolescence | 18–20 years | Single-dose 10 μg. At 1 month: 97.7% for pre-booster detectable anti-HBs. 88.8% for undetectable pre-booster level. |

2 more doses; 100% | Italy | [47] |

| 7 | 3 doses; first year of life (2 days of birth, 1.5 and 9 months) | 20 years | Single-dose 20 μg; 97.1% after 4 weeks. | NA | Iran | [37] |

| 8 | 3–4 doses; all vaccinated during adulthood | 20–30 years | Single-dose 20 μg. For < 10 mIU/mL *: 70% at day 7 and 100% at 1 month. For > 10 mIU/mL *: 100% at both day 7 and 1 month. |

NA | Canada and Belgium | [40] |

5. Conclusions

References

- McAleer, W.J.; Buynak, E.B.; Maigetter, R.Z.; Wampler, D.E.; Miller, W.J.; Hilleman, M.R. Human hepatitis B vaccine from recombinant yeast. Nature 1984, 307, 178–180.

- WHO. Hepatitis B; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Polaris Observatory, C. Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: A modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 383–403.

- WHO. Global Progress Report on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2021: Accountability for the Global Health Sector Strategies 2016–2021: Actions for Impact; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Van Damme, P.; Ward, J.; Shouval, D.; Wiersma, S.; Zanetti, A. Hepatitis B Vaccines. In Vaccines; Plotkin, S.A., Orenstein, W.A., Offit, P.A., Edwards, K.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; Volume 205, p. 234.

- Klinger, G.; Chodick, G.; Levy, I. Long-term immunity to hepatitis B following vaccination in infancy: Real-world data analysis. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2288–2292.

- Tajiri, K.; Shimizu, Y. Unsolved problems and future perspectives of hepatitis B virus vaccination. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 7074–7083.

- Bekele, Y.; Yibeltal, D.; Bobosha, K.; Andargie, T.E.; Lemma, M.; Gebre, M.; Mekonnen, E.; Habtewold, A.; Nilsson, A.; Aseffa, A.; et al. T follicular helper cells and antibody response to Hepatitis B virus vaccine in HIV-1 infected children receiving ART. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8956.

- Kerneis, S.; Launay, O.; Turbelin, C.; Batteux, F.; Hanslik, T.; Boelle, P.Y. Long-term immune responses to vaccination in HIV-infected patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis 2014, 58, 1130–1139.

- Kim, H.N.; Harrington, R.D.; Crane, H.M.; Dhanireddy, S.; Dellit, T.H.; Spach, D.H. Hepatitis B vaccination in HIV-infected adults: Current evidence, recommendations and practical considerations. Int. J. STD AIDS 2009, 20, 595–600.

- Mizusawa, M.; Perlman, D.C.; Lucido, D.; Salomon, N. Rapid loss of vaccine-acquired hepatitis B surface antibody after three doses of hepatitis B vaccination in HIV-infected persons. Int. J. STD AIDS 2014, 25, 201–206.

- Whitaker, J.A.; Rouphael, N.G.; Edupuganti, S.; Lai, L.; Mulligan, M.J. Strategies to increase responsiveness to hepatitis B vaccination in adults with HIV-1. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 966–976.

- Collaborators, G.H. Global, regional, and national sex-specific burden and control of the HIV epidemic, 1990-2019, for 204 countries and territories: The Global Burden of Diseases Study 2019. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e633–e651.

- Cheng, Z.; Lin, P.; Cheng, N. HBV/HIV Coinfection: Impact on the Development and Clinical Treatment of Liver Diseases. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 713981.

- Bianco, E.; Stroffolini, T.; Spada, E.; Szklo, A.; Marzolini, F.; Ragni, P.; Gallo, G.; Balocchini, E.; Parlato, A.; Sangalli, M.; et al. Case fatality rate of acute viral hepatitis in Italy: 1995-2000. An update. Dig. Liver Dis. 2003, 35, 404–408.

- Kourtis, A.P.; Bulterys, M.; Hu, D.J.; Jamieson, D.J. HIV-HBV coinfection—a global challenge. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1749–1752.

- Levy, V.; Grant, R.M. Antiretroviral therapy for hepatitis B virus-HIV-coinfected patients: Promises and pitfalls. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 904–910.

- Parvez, M.K. HBV and HIV co-infection: Impact on liver pathobiology and therapeutic approaches. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 121–126.

- Mancinelli, S.; Pirillo, M.F.; Liotta, G.; Andreotti, M.; Mphwere, R.; Amici, R.; Marazzi, M.C.; Vella, S.; Palombi, L.; Giuliano, M. Antibody response to hepatitis B vaccine in HIV-exposed infants in Malawi and correlation with HBV infection acquisition. J. Med. Virol. 2018, 90, 1172–1176.

- Lapphra, K.; Angkhananukit, P.; Saihongthong, S.; Phongsamart, W.; Wittawatmongkol, O.; Rungmaitree, S.; Chokephaibulkit, K. Persistence of Hepatitis B Immunity Following 3-dose Infant Primary Series in HIV-infected Thai Adolescents and Immunologic Response to Revaccination. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017, 36, 863–868.

- Abushady, E.A.; Gameel, M.M.; Klena, J.D.; Ahmed, S.F.; Abdel-Wahab, K.S.; Fahmy, S.M. HBV vaccine efficacy and detection and genotyping of vaccinee asymptomatic breakthrough HBV infection in Egypt. World J. Hepatol. 2011, 3, 147–156.

- Mendy, M.; Peterson, I.; Hossin, S.; Peto, T.; Jobarteh, M.L.; Jeng-Barry, A.; Sidibeh, M.; Jatta, A.; Moore, S.E.; Hall, A.J.; et al. Observational study of vaccine efficacy 24 years after the start of hepatitis B vaccination in two Gambian villages: No need for a booster dose. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58029.

- Powell, E.A.; Razeghi, S.; Zucker, S.; Blackard, J.T. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in a Previously Vaccinated Injection Drug User. Hepat. Mon. 2016, 16, e34758.

- Gerlich, W.H. Breakthrough of hepatitis B virus escape mutants after vaccination and virus reactivation. J. Clin. Virol. 2006, 36, S18–S22.

- Singh, K.P.; Crane, M.; Audsley, J.; Avihingsanon, A.; Sasadeusz, J.; Lewin, S.R. HIV-hepatitis B virus coinfection: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. AIDS 2017, 31, 2035–2052.

- De Clercq, E.; Ferir, G.; Kaptein, S.; Neyts, J. Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections. Viruses 2010, 2, 1279–1305.

- Mutwa, P.R.; Boer, K.R.; Rusine, J.B.; Muganga, N.; Tuyishimire, D.; Reiss, P.; Lange, J.M.; Geelen, S.P. Hepatitis B virus prevalence and vaccine response in HIV-infected children and adolescents on combination antiretroviral therapy in Kigali, Rwanda. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013, 32, 246–251.

- Paitoonpong, L.; Suankratay, C. Immunological response to hepatitis B vaccination in patients with AIDS and virological response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 40, 54–58.

- Irungu, E.; Mugo, N.; Ngure, K.; Njuguna, R.; Celum, C.; Farquhar, C.; Dhanireddy, S.; Baeten, J.M. Immune response to hepatitis B virus vaccination among HIV-1 infected and uninfected adults in Kenya. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 402–410.

- Lopes, V.B.; Hassing, R.J.; de Vries-Sluijs, T.E.; El Barzouhi, A.; Hansen, B.E.; Schutten, M.; de Man, R.A.; van der Ende, M.E. Long-term response rates of successful hepatitis B vaccination in HIV-infected patients. Vaccine 2013, 31, 1040–1044.

- Bekele, Y.; Lemma, M.; Bobosha, K.; Yibeltal, D.; Nasi, A.; Gebre, M.; Nilsson, A.; Aseffa, A.; Howe, R.; Chiodi, F. Homing defects of B cells in HIV-1 infected children impair vaccination responses. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2348–2355.

- Pippi, F.; Bracciale, L.; Stolzuoli, L.; Giaccherini, R.; Montomoli, E.; Gentile, C.; Filetti, S.; De Luca, A.; Cellesi, C. Serological response to hepatitis B virus vaccine in HIV-infected children in Tanzania. HIV Med. 2008, 9, 519–525.

- Herrero-Fernandez, I.; Pacheco, Y.M.; Genebat, M.; Rodriguez-Mendez, M.D.M.; Lozano, M.D.C.; Polaino, M.J.; Rosado-Sanchez, I.; Tarancon-Diez, L.; Munoz-Fernandez, M.A.; Ruiz-Mateos, E.; et al. Association between a Suppressive Combined Antiretroviral Therapy Containing Maraviroc and the Hepatitis B Virus Vaccine Response. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, AAC.02050-17.

- Cagigi, A.; Nilsson, A.; Pensieroso, S.; Chiodi, F. Dysfunctional B-cell responses during HIV-1 infection: Implication for influenza vaccination and highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 499–503.

- Amu, S.; Ruffin, N.; Rethi, B.; Chiodi, F. Impairment of B-cell functions during HIV-1 infection. AIDS 2013, 27, 2323–2334.

- Poonia, B.; Ayithan, N.; Nandi, M.; Masur, H.; Kottilil, S. HBV induces inhibitory FcRL receptor on B cells and dysregulates B cell-T follicular helper cell axis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15296.

- Burton, A.R.; Pallett, L.J.; McCoy, L.E.; Suveizdyte, K.; Amin, O.E.; Swadling, L.; Alberts, E.; Davidson, B.R.; Kennedy, P.T.; Gill, U.S.; et al. Circulating and intrahepatic antiviral B cells are defective in hepatitis B. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 4588–4603.

- Pensieroso, S.; Galli, L.; Nozza, S.; Ruffin, N.; Castagna, A.; Tambussi, G.; Hejdeman, B.; Misciagna, D.; Riva, A.; Malnati, M.; et al. B-cell subset alterations and correlated factors in HIV-1 infection. AIDS 2013, 27, 1209–1217.

- Bagheri-Jamebozorgi, M.; Keshavarz, J.; Nemati, M.; Mohammadi-Hossainabad, S.; Rezayati, M.T.; Nejad-Ghaderi, M.; Jamalizadeh, A.; Shokri, F.; Jafarzadeh, A. The persistence of anti-HBs antibody and anamnestic response 20 years after primary vaccination with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine at infancy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 3731–3736.

- Poorolajal, J.; Mahmoodi, M.; Majdzadeh, R.; Nasseri-Moghaddam, S.; Haghdoost, A.; Fotouhi, A. Long-term protection provided by hepatitis B vaccine and need for booster dose: A meta-analysis. Vaccine 2010, 28, 623–631.

- Salama, I.I.; Sami, S.M.; Said, Z.N.; Salama, S.I.; Rabah, T.M.; Abdel-Latif, G.A.; Elmosalami, D.M.; Saleh, R.M.; Abdel Mohsin, A.M.; Metwally, A.M.; et al. Early and long term anamnestic response to HBV booster dose among fully vaccinated Egyptian children during infancy. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2005–2011.

- Van Damme, P.; Dionne, M.; Leroux-Roels, G.; Van Der Meeren, O.; Di Paolo, E.; Salaun, B.; Surya Kiran, P.; Folschweiller, N. Persistence of HBsAg-specific antibodies and immune memory two to three decades after hepatitis B vaccination in adults. J. Viral Hepat. 2019, 26, 1066–1075.

- Cocchio, S.; Baldo, V.; Volpin, A.; Fonzo, M.; Floreani, A.; Furlan, P.; Mason, P.; Trevisan, A.; Scapellato, M.L. Persistence of Anti-Hbs after up to 30 Years in Health Care Workers Vaccinated against Hepatitis B Virus. Vaccines 2021, 9, 323.

- Zhao, Y.L.; Han, B.H.; Zhang, X.J.; Pan, L.L.; Zhou, H.S.; Gao, Z.; Hao, Z.Y.; Wu, Z.W.; Ma, T.L.; Wang, F.; et al. Immune persistence 17 to 20 years after primary vaccination with recombination hepatitis B vaccine (CHO) and the effect of booster dose vaccination. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 482.

- Wu, Z.; Yao, J.; Bao, H.; Chen, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Ren, J.; Xu, K.J.; et al. The effects of booster vaccination of hepatitis B vaccine on children 5-15 years after primary immunization: A 5-year follow-up study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 1251–1256.

- Bini, C.; Grazzini, M.; Chellini, M.; Mucci, N.; Arcangeli, G.; Tiscione, E.; Bonanni, P. Is hepatitis B vaccination performed at infant and adolescent age able to provide long-term immunological memory? An observational study on healthcare students and workers in Florence, Italy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 450–455.

- Bianchi, F.P.; Gallone, M.S.; Gallone, M.F.; Larocca, A.M.V.; Vimercati, L.; Quarto, M.; Tafuri, S. HBV seroprevalence after 25 years of universal mass vaccination and management of non-responders to the anti-Hepatitis B vaccine: An Italian study among medical students. J. Viral Hepat. 2019, 26, 136–144.

- Schwarz, T.F.; Behre, U.; Adelt, T.; Donner, M.; Suryakiran, P.V.; Janssens, W.; Mesaros, N.; Panzer, F. Long-term antibody persistence against hepatitis B in adolescents 14–15-years of age vaccinated with 4 doses of hexavalent DTPa-HBV-IPV/Hib vaccine in infancy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 235–241.

- Papadopoli, R.; De Sarro, C.; Torti, C.; Pileggi, C.; Pavia, M. Is There Any Opportunity to Provide an HBV Vaccine Booster Dose Before Anti-Hbs Titer Vanishes? Vaccines 2020, 8, 227.

- European Consensus Group on Hepatitis B Immunity. Are booster immunisations needed for lifelong hepatitis B immunity? Lancet 2000, 355, 561–565.

- Leuridan, E.; Van Damme, P. Hepatitis B and the need for a booster dose. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 68–75.

- Jin, H.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, P. Comparison of Accelerated and Standard Hepatitis B Vaccination Schedules in High-Risk Healthy Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133464.

- Van Herck, K.; Leuridan, E.; Van Damme, P. Schedules for hepatitis B vaccination of risk groups: Balancing immunogenicity and compliance. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2007, 83, 426–432.

- Giacomet, V.; Masetti, M.; Nannini, P.; Forlanini, F.; Clerici, M.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Trabattoni, D. Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses after a booster dose of HBV vaccine in HIV-infected children, adolescents and young adults. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192638.

- Lao-Araya, M.; Puthanakit, T.; Aurpibul, L.; Taecharoenkul, S.; Sirisanthana, T.; Sirisanthana, V. Prevalence of protective level of hepatitis B antibody 3 years after revaccination in HIV-infected children on antiretroviral therapy. Vaccine 2011, 29, 3977–3981.

- Abzug, M.J.; Warshaw, M.; Rosenblatt, H.M.; Levin, M.J.; Nachman, S.A.; Pelton, S.I.; Borkowsky, W.; Fenton, T.; International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1024 and P1061s Protocol Teams. Immunogenicity and immunologic memory after hepatitis B virus booster vaccination in HIV-infected children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 935–946.

- Sit, D.; Esen, B.; Atay, A.E.; Kayabasi, H. Is hemodialysis a reason for unresponsiveness to hepatitis B vaccine? Hepatitis B virus and dialysis therapy. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 761–768.

- Gilbert, C.L.; Stek, J.E.; Villa, G.; Klopfer, S.O.; Martin, J.C.; Schodel, F.P.; Bhuyan, P.K. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant hepatitis B vaccine manufactured by a modified process in renal pre-dialysis and dialysis patients. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6521–6526.

- Chaves, S.S.; Daniels, D.; Cooper, B.W.; Malo-Schlegel, S.; Macarthur, S.; Robbins, K.C.; Kobetitsch, J.F.; McDaniel, A.; D’Avella, J.F.; Alter, M.J. Immunogenicity of hepatitis B vaccine among hemodialysis patients: Effect of revaccination of non-responders and duration of protection. Vaccine 2011, 29, 9618–9623.

- Fourati, S.; Cristescu, R.; Loboda, A.; Talla, A.; Filali, A.; Railkar, R.; Schaeffer, A.K.; Favre, D.; Gagnon, D.; Peretz, Y.; et al. Pre-vaccination inflammation and B-cell signalling predict age-related hyporesponse to hepatitis B vaccination. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10369.