| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Natasha Elizabeth Mckean | + 6208 word(s) | 6208 | 2021-12-14 03:58:18 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 6208 | 2021-12-23 03:14:55 | | |

Video Upload Options

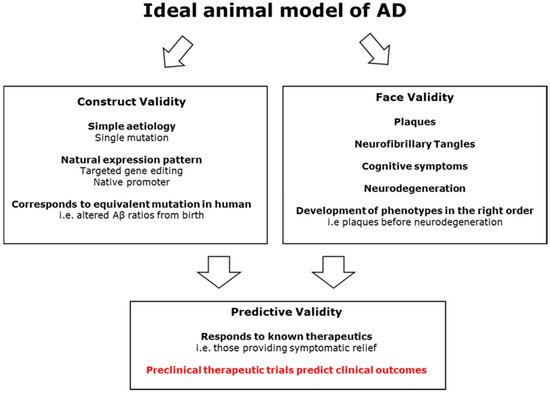

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the looming health crises of the near future. Increasing lifespans and better medical treatment for other conditions mean that the prevalence of this disease is expected to triple by 2050. The impact of AD includes both the large toll on individuals and their families as well as a large financial cost to society. So far, we have no way to prevent, slow, or cure the disease. Current medications can only alleviate some of the symptoms temporarily. Many animal models of AD have been created, with the first transgenic mouse model in 1995. Mouse models have been beset by challenges, and no mouse model fully captures the symptomatology of AD without multiple genetic mutations and/or transgenes, some of which have never been implicated in human AD. Over 25 years later, many mouse models have been given an AD-like disease and then ‘cured’ in the lab, only for the treatments to fail in clinical trials.

1. Introduction

2. Modelling AD in Animals

3. Small Animal Models of AD

3.1. Mouse Models

3.1.1. Plaque Pathology in Mouse Models

| Name | Type of Modification |

FAD Mutations | MAPT Mutations |

Plaques | Tangles | Neurodegeneration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDAPP | Transgenesis | Indiana in APP | X | [21] | |||

| Tg2576 | Transgenesis | Swedish in APP | X | [22] | |||

| TgCRND8 | Transgenesis | Swedish and Indiana in APP | X | [23] | |||

| PSAPP | Transgenesis | Swedish in APP, M146L in PSEN1 | X | [24] | |||

| BRI-Aβ40 | Transgenesis | Aβ1–40 peptide | [25] | ||||

| BRI-Aβ42 | Transgenesis | Aβ1–42 peptide | X | [25] | |||

| 5XFAD | Transgenesis | Swedish, Florida, London in APP. M146L and L286V in PSEN1 | X | X | [26] | ||

| JNPL3 | Transgenesis | P301L in MAPT | X | X | [27] | ||

| rTg4510 | Transgenesis | P301L in MAPT | X | X | [28] | ||

| 3xTg | Transgenesis | Swedish in APP, M146L in PSEN1 | P301L in MAPT | X | X | X | [29] |

| TAPP | Transgenesis | Swedish in APP | P301L in MAPT | X | X | X | [30] |

3.1.2. Replicating AD Tau Pathology

3.1.3. Construct Validity of Transgenic Mouse Models of AD

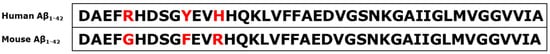

3.1.4. Murine APP Knock in Models

3.1.5. Murine PSEN1 Knock in Models

3.1.6. Construct Validity of MAPT Mouse Models

3.1.7. Predictive Validity of Murine Models

3.1.8. Murine Model Summary

3.2. Rat Models of AD

4. Large Animal Models in AD Research

| Species | Scientific Name | Plaques | Tangles | Neurodegeneration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chimpanzee | Pan troglodytes | X | X | [120][121] | |

| Orang-Utan | Pongo spp. | X | [122] | ||

| Western Gorilla | Gorilla | X | X | [123][124] | |

| Eastern Gorilla | Gorilla beringei | X | X | [125] | |

| Cynomolgus Monkey | Macaca fascicularis | X | X | [126][127][128][129] | |

| Rhesus Macaque | Macaca mulattas | X | X | [130][131] | |

| Stump Tailed macaque | Macaca arctoides | X | X | [132] | |

| Vervet Monkey | Chlorocebus aethiops | X | X | [133] | |

| Baboon | Papio hamadryas | X | X | [134][135][136] | |

| Cotton Topped Tamarin | Saguinus oedipus | X | [137] | ||

| Mouse Lemur | Microcebus murinus | X | X | X | [138][139][140] |

| Common Marmoset | Callithrix jacchus | X | X | [141][142] | |

| Squirrel Monkey | Saimiri sciureus | X | [143][144] | ||

| Pigs | Sus domesticus | X * | X * | [145] | |

| Domestic Sheep | Ovis aries | X | X | [118][146][147][148] | |

| Domestic Goat | Capra hircus | X | [146] | ||

| Bactrian Camel | Camelus bactrianus | X | [149] | ||

| Reindeer | Rangifer tarandus | X | [150] | ||

| American Bison | Bison | X | [150] | ||

| Domestic Dog | Canis familiaris | X | X | X | [151][152][153][154][155][156] |

| Domestic Cat | Felis catus | X | X | X | [157][158] |

| Leopard Cat | Prionailurus bengalensis | X | X | [159] | |

| Polar Bear | Ursus maritimus | X | [160] | ||

| Brown Bear | Ursus arctos | X | [160] | ||

| Black Bear | Ursus americanus | X | [161] | ||

| Wolverine | Gulo | X | X | [162] | |

| Harbor Seal species | Phoca largha, Phoca vitulina | X | X | [163] | |

| Sea Lion species | Eumetopias jubatus, Zalophus californianus, Neophoca cinerea | X | X | [163] | |

| Walrus | Odobenus rosmarus | X | X | [163] |

4.1. Primate Models of AD

4.2. Larger Non-Primate Mammalian Models

4.2.1. Larger Companion Animals

4.2.2. Farm Animals

4.2.3. Pigs

4.2.4. Sheep

References

- Khachaturian, Z.S. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Neurol. 1985, 42, 1097–1105.

- Hebert, L.E.; Beckett, L.A.; Scherr, P.A.; Evans, D.A. Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2001, 15, 169–173.

- Sloane, P.D.; Zimmerman, S.; Suchindran, C.; Reed, P.; Wang, L.; Boustani, M.; Sudha, S. The public health impact of Alzheimer’s disease, 2000–2050: Potential implication of treatment advances. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2002, 23, 213–231.

- Fox, P.J.; Kohatsu, N.; Max, W.; Arnsberger, P. Estimating the costs of caring for people with Alzheimer disease in California: 2000–2040. J. Public Health Policy 2001, 22, 88–97.

- Katzman, R.; Fox, P. The World-Wide Impact of Dementia. Projections of Prevalance and Costs. In Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s Disease: From Gene to Prevention; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1999; pp. 1–17.

- Tagarelli, A.; Piro, A.; Tagarelli, G.; Lagonia, P.; Quattrone, A. Alois Alzheimer: A hundred years after the discovery of the eponymous disorder. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006, 2, 196.

- Glenner, G.G.; Wong, C.W. Alzheimer’s disease: Initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984, 120, 885–890.

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G. A century of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 2006, 314, 777–781.

- Kidd, M. Paired helical filaments in electron microscopy of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 1963, 197, 192–193.

- Cummings, J.; Lee, G.; Zhong, K.; Fonseca, J.; Taghva, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2021. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2021, 7, e12179.

- Cummings, J.; Feldman, H.H.; Scheltens, P. The “rights” of precision drug development for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 1–14.

- Cummings, J.L.; Morstorf, T.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: Few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 1–7.

- Justice, M.J.; Dhillon, P. Using the Mouse to Model Human Disease: Increasing Validity and Reproducibility; The Company of Biologists Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2016.

- Toledano, A.; Alvarez, M.I. Lesion-Induced Vertebrate Models of Alzheimer Dementia. Neuromethods 2011, 48, 295–345.

- Beach, T.G.; Potter, P.E.; Kuo, Y.M.; Emmerling, M.R.; Durham, R.A.; Webster, S.D.; Walker, D.G.; Sue, L.I.; Scott, S.; Layne, K.J.; et al. Cholinergic deafferentation of the rabbit cortex: A new animal model of A beta deposition. Neurosci. Lett. 2000, 283, 9–12.

- Wenk, G.L. A Primate Model of Alzheimers-Disease. Behav. Brain Res. 1993, 57, 117–122.

- Ridley, R.M.; Murray, T.K.; Johnson, J.A.; Baker, H.F. Learning Impairment Following Lesion of the Basal Nucleus of Meynert in the Marmoset—Modification by Cholinergic Drugs. Brain Res. 1986, 376, 108–116.

- Coyle, J.T.; Price, D.L.; Delong, M.R. Alzheimers-Disease—A Disorder of Cortical Cholinergic Innervation. Science 1983, 219, 1184–1190.

- Whitehouse, P.J.; Price, D.L.; Struble, R.G.; Clark, A.W.; Coyle, J.T.; Delong, M.R. Alzheimers-Disease and Senile Dementia—Loss of Neurons in the Basal Forebrain. Science 1982, 215, 1237–1239.

- McGonigle, P. Animal models of CNS disorders. Biochem. Pharm. 2014, 87, 140–149.

- Games, D.; Adams, D.; Alessandrini, R.; Barbour, R.; Borthelette, P.; Blackwell, C.; Carr, T.; Clemens, J.; Donaldson, T.; Gillespie, F. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. Nature 1995, 373, 523–527.

- Hsiao, K.; Chapman, P.; Nilsen, S.; Eckman, C. Correlative memory deficits, A beta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 1996, 274, 98.

- Chishti, M.A.; Yang, D.-S.; Janus, C.; Phinney, A.L.; Horne, P.; Pearson, J.; Strome, R.; Zuker, N.; Loukides, J.; French, J. Early-onset amyloid deposition and cognitive deficits in transgenic mice expressing a double mutant form of amyloid precursor protein 695. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 21562–21570.

- Holcomb, L.; Gordon, M.N.; McGowan, E.; Yu, X.; Benkovic, S.; Jantzen, P.; Wright, K.; Saad, I.; Mueller, R.; Morgan, D. Accelerated Alzheimer-type phenotype in transgenic mice carrying both mutant amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 transgenes. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 97–100.

- McGowan, E.; Pickford, F.; Kim, J.; Onstead, L.; Eriksen, J.; Yu, C.; Skipper, L.; Murphy, M.P.; Beard, J.; Das, P. Aβ42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron 2005, 47, 191–199.

- Oakley, H.; Cole, S.L.; Logan, S.; Maus, E.; Shao, P.; Craft, J.; Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.; Ohno, M.; Disterhoft, J.; Van Eldik, L. Intraneuronal β-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: Potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10129–10140.

- Lewis, J.; McGowan, E.; Rockwood, J.; Melrose, H.; Nacharaju, P.; Van Slegtenhorst, M.; Gwinn-Hardy, K.; Murphy, M.P.; Baker, M.; Yu, X. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 402–405.

- Ramsden, M.; Kotilinek, L.; Forster, C.; Paulson, J.; McGowan, E.; SantaCruz, K.; Guimaraes, A.; Yue, M.; Lewis, J.; Carlson, G.; et al. Age-dependent neurofibrillary tangle formation, neuron loss, and memory impairment in a mouse model of human tauopathy (P301L). J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 10637–10647.

- Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A.; Kitazawa, M.; Tseng, B.P.; LaFerla, F.M. Amyloid deposition precedes tangle formation in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2003, 24, 1063–1070.

- Lewis, J.; Dickson, D.W.; Lin, W.-L.; Chisholm, L.; Corral, A.; Jones, G.; Yen, S.-H.; Sahara, N.; Skipper, L.; Yager, D. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science 2001, 293, 1487–1491.

- Irizarry, M.C.; Soriano, F.; McNamara, M.; Page, K.J.; Schenk, D.; Games, D.; Hyman, B.T. Abeta deposition is associated with neuropil changes, but not with overt neuronal loss in the human amyloid precursor protein V717F (PDAPP) transgenic mouse. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 7053–7059.

- King, D.L.; Arendash, G.W. Behavioral characterization of the Tg2576 transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease through 19 months. Physiol. Behav. 2002, 75, 627–642.

- Westerman, M.A.; Cooper-Blacketer, D.; Mariash, A.; Kotilinek, L.; Kawarabayashi, T.; Younkin, L.H.; Carlson, G.A.; Younkin, S.G.; Ashe, K.H. The relationship between Aβ and memory in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 1858–1867.

- Kotilinek, L.A.; Bacskai, B.; Westerman, M.; Kawarabayashi, T.; Younkin, L.; Hyman, B.T.; Younkin, S.; Ashe, K.H. Reversible memory loss in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 6331–6335.

- Janus, C.; Phinney, A.L.; Chishti, M.A.; Westaway, D. New developments in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2001, 1, 451–457.

- Borchelt, D.R.; Thinakaran, G.; Eckman, C.B.; Lee, M.K.; Davenport, F.; Ratovitsky, T.; Prada, C.-M.; Kim, G.; Seekins, S.; Yager, D. Familial Alzheimer’s disease–linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Aβ1–42/1–40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 1996, 17, 1005–1013.

- Citron, M.; Westaway, D.; Xia, W.; Carlson, G.; Diehl, T.; Levesque, G.; Johnson-Wood, K.; Lee, M.; Seubert, P.; Davis, A.; et al. Mutant presenilins of Alzheimer’s disease increase production of 42-residue amyloid beta-protein in both transfected cells and transgenic mice. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 67–72.

- Duff, K.; Eckman, C.; Zehr, C.; Yu, X.; Prada, C.-M.; Perez-Tur, J.; Hutton, M.; Buee, L.; Harigaya, Y.; Yager, D. Increased amyloid-β42 (43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1. Nature 1996, 383, 710–713.

- Borchelt, D.R.; Ratovitski, T.; Van Lare, J.; Lee, M.K.; Gonzales, V.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G.; Price, D.L.; Sisodia, S.S. Accelerated amyloid deposition in the brains of transgenic mice coexpressing mutant presenilin 1 and amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron 1997, 19, 939–945.

- Jawhar, S.; Trawicka, A.; Jenneckens, C.; Bayer, T.A.; Wirths, O. Motor deficits, neuron loss, and reduced anxiety coinciding with axonal degeneration and intraneuronal Abeta aggregation in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 196.e29–196.e40.

- Chen, F.; David, D.; Ferrari, A.; Gotz, J. Posttranslational modifications of tau—Role in human tauopathies and modeling in transgenic animals. Curr. Drug Targets 2004, 5, 503–515.

- Rademakers, R.; Cruts, M.; van Broeckhoven, C. The role of tau (MAPT) in frontotemporal dementia and related tauopathies. Hum. Mutat. 2004, 24, 277–295.

- Santacruz, K.; Lewis, J.; Spires, T.; Paulson, J.; Kotilinek, L.; Ingelsson, M.; Guimaraes, A.; Deture, M.; Ramsden, M.; McGowan, E. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science 2005, 309, 476–481.

- Eriksen, J.L.; Janus, C.G. Plaques, tangles, and memory loss in mouse models of neurodegeneration. Behav. Genet. 2007, 37, 79–100.

- Yamada, T.; Sasaki, H.; Furuya, H.; Miyata, T.; Goto, I.; Sakaki, Y. Complementary DNA for the mouse homolog of the human amyloid beta protein precursor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987, 149, 665–671.

- Liu, K.; Doms, R.W.; Lee, V.M.-Y. Glu11 site cleavage and N-terminally truncated Aβ production upon BACE overexpression. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 3128–3136.

- Cai, H.; Wang, Y.; McCarthy, D.; Wen, H.; Borchelt, D.R.; Price, D.L.; Wong, P.C. BACE1 is the major -secretase for generation of A peptides by neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 233.

- Kawasumi, M.; Chiba, T.; Yamada, M.; Miyamae-Kaneko, M.; Matsuoka, M.; Nakahara, J.; Tomita, T.; Iwatsubo, T.; Kato, S.; Aiso, S.; et al. Targeted introduction of V642I mutation in amyloid precursor protein gene causes functional abnormality resembling early stage of Alzheimer’s disease in aged mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 19, 2826–2838.

- Tanaka, S.; Shiojiri, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Kitaguchi, N.; Ito, H.; Kameyama, M.; Kimura, J.; Nakamura, S.; Ueda, K. Tissue-specific expression of three types of beta-protein precursor mRNA: Enhancement of protease inhibitor-harboring types in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989, 165, 1406–1414.

- Tanaka, S.; Liu, L.; Kimura, J.; Shiojiri, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Kitaguchi, N.; Nakamura, S.; Ueda, K. Age-related changes in the proportion of amyloid precursor protein mRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1992, 15, 303–310.

- Moir, R.D.; Lynch, T.; Bush, A.I.; Whyte, S.; Henry, A.; Portbury, S.; Multhaup, G.; Small, D.H.; Tanzi, R.E.; Beyreuther, K.; et al. Relative increase in Alzheimer’s disease of soluble forms of cerebral Abeta amyloid protein precursor containing the Kunitz protease inhibitory domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 5013–5019.

- Higgins, L.S.; Catalano, R.; Quon, D.; Cordell, B. Transgenic mice expressing human beta-APP751, but not mice expressing beta-APP695, display early Alzheimer’s disease-like histopathology. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993, 695, 224–227.

- Sasahara, M.; Fries, J.W.; Raines, E.W.; Gown, A.M.; Westrum, L.E.; Frosch, M.P.; Bonthron, D.T.; Ross, R.; Collins, T. PDGF B-chain in neurons of the central nervous system, posterior pituitary, and in a transgenic model. Cell 1991, 64, 217–227.

- Caroni, P. Overexpression of growth-associated proteins in the neurons of adult transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. Methods 1997, 71, 3–9.

- Asante, E.A.; Gowland, I.; Linehan, J.M.; Mahal, S.P.; Collinge, J. Expression pattern of a mini human PrP gene promoter in transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 10, 1–7.

- Sturchler-Pierrat, C.; Abramowski, D.; Duke, M.; Wiederhold, K.-H.; Mistl, C.; Rothacher, S.; Ledermann, B.; Bürki, K.; Frey, P.; Paganetti, P.A. Two amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models with Alzheimer disease-like pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 13287–13292.

- Jankowsky, J.L.; Slunt, H.H.; Gonzales, V.; Savonenko, A.V.; Wen, J.C.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G.; Younkin, L.H.; Lester, H.A.; Younkin, S.G. Persistent amyloidosis following suppression of Aβ production in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e355.

- Yasuda, M.; Johnson-Venkatesh, E.M.; Zhang, H.; Parent, J.M.; Sutton, M.A.; Umemori, H. Multiple forms of activity-dependent competition refine hippocampal circuits in vivo. Neuron 2011, 70, 1128–1142.

- Liu, P.; Paulson, J.B.; Forster, C.L.; Shapiro, S.L.; Ashe, K.H.; Zahs, K.R. Characterization of a novel mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease—Amyloid pathology and unique β-Amyloid oligomer profile. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e126317.

- Reaume, A.G.; Howland, D.S.; Trusko, S.P.; Savage, M.J.; Lang, D.M.; Greenberg, B.D.; Siman, R.; Scott, R.W. Enhanced amyloidogenic processing of the β-amyloid precursor protein in gene-targeted mice bearing the Swedish familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations and a “humanized” Aβ sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 23380–23388.

- Li, H.; Guo, Q.; Inoue, T.; Polito, V.A.; Tabuchi, K.; Hammer, R.E.; Pautler, R.G.; Taffet, G.E.; Zheng, H. Vascular and parenchymal amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer disease knock-in mouse model: Interplay with cerebral blood flow. Mol. Neurodegener 2014, 9, 28.

- Saito, T.; Matsuba, Y.; Mihira, N.; Takano, J.; Nilsson, P.; Itohara, S.; Iwata, N.; Saido, T.C. Single App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 661–663.

- Masuda, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kogo, N.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Itohara, S. Cognitive deficits in single App knock-in mouse models. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2016, 135, 73–82.

- Jankowsky, J.L.; Zheng, H. Practical considerations for choosing a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener 2017, 12, 89.

- Anantharaman, M.; Tangpong, J.; Keller, J.N.; Murphy, M.P.; Markesbery, W.R.; Kiningham, K.K.; Clair, D.K.S. β-Amyloid mediated nitration of manganese superoxide dismutase: Implication for oxidative stress in a APPNLH/NLH X PS-1P264L/P264L double knock-in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 168, 1608–1618.

- Zhang, C.; McNeil, E.; Dressler, L.; Siman, R. Long-lasting impairment in hippocampal neurogenesis associated with amyloid deposition in a knock-in mouse model of familial Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 204, 77–87.

- Saito, T.; Matsuba, Y.; Yamazaki, N.; Hashimoto, S.; Saido, T.C. Calpain activation in Alzheimer’s model mice is an artifact of APP and presenilin overexpression. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 9933–9936.

- Hashimoto, S.; Ishii, A.; Kamano, N.; Watamura, N.; Saito, T.; Ohshima, T.; Yokosuka, M.; Saido, T.C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease: Overexpression paradigm versus knockin paradigm. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 3118–3125.

- Drummond, E.; Wisniewski, T. Alzheimer’s disease: Experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 155–175.

- Dickson, D.W.; Crystal, H.A.; Mattiace, L.A.; Masur, D.M.; Blau, A.D.; Davies, P.; Yen, S.-H.; Aronson, M.K. Identification of normal and pathological aging in prospectively studied nondemented elderly humans. Neurobiol. Aging 1992, 13, 179–189.

- Nakano, Y.; Kondoh, G.; Kudo, T.; Imaizumi, K.; Kato, M.; Miyazaki, J.i.; Tohyama, M.; Takeda, J.; Takeda, M. Accumulation of murine amyloidβ42 in a gene-dosage-dependent manner in PS1 ‘knock-in’mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 2577–2581.

- Flood, D.G.; Reaume, A.G.; Dorfman, K.S.; Lin, Y.-G.; Lang, D.M.; Trusko, S.P.; Savage, M.J.; Annaert, W.G.; De Strooper, B.; Siman, R. FAD mutant PS-1 gene-targeted mice: Increased Aβ42 and Aβ deposition without APP overproduction. Neurobiol. Aging 2002, 23, 335–348.

- Holcomb, L.A.; Gordon, M.N.; Jantzen, P.; Hsiao, K.; Duff, K.; Morgan, D. Behavioral changes in transgenic mice expressing both amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 mutations: Lack of association with amyloid deposits. Behav. Genet. 1999, 29, 177–185.

- Huang, X.; Yee, B.; Nag, S.; Chan, S.; Tang, F. Behavioral and neurochemical characterization of transgenic mice carrying the human presenilin-1 gene with or without the leucine-to-proline mutation at codon 235. Exp. Neurol. 2003, 183, 673–681.

- Janus, C.; D’Amelio, S.; Amitay, O.; Chishti, M.; Strome, R.; Fraser, P.; Carlson, G.; Roder, J.; George–Hyslop, P.S.; Westaway, D. Spatial learning in transgenic mice expressing human presenilin 1 (PS1) transgenes. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 541–549.

- Dineley, K.T.; Xia, X.; Bui, D.; Sweatt, J.D.; Zheng, H. Accelerated plaque accumulation, associative learning deficits, and up-regulation of α7 nicotinic receptor protein in transgenic mice co-expressing mutant human presenilin 1 and amyloid precursor proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 22768–22780.

- Jankowsky, J.L.; Fadale, D.J.; Anderson, J.; Xu, G.M.; Gonzales, V.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G.; Lee, M.K.; Younkin, L.H.; Wagner, S.L. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue β-amyloid peptide in vivo: Evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific γ secretase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 159–170.

- Casas, C.; Sergeant, N.; Itier, J.-M.; Blanchard, V.; Wirths, O.; van der Kolk, N.; Vingtdeux, V.; van de Steeg, E.; Ret, G.; Canton, T. Massive CA1/2 neuronal loss with intraneuronal and N-terminal truncated Aβ 42 accumulation in a novel Alzheimer transgenic model. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 165, 1289–1300.

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G.; Jakes, R.; Rutherford, D.; Crowther, R.A. Multiple Isoforms of Human Microtubule-Associated Protein-Tau—Sequences and Localization in Neurofibrillary Tangles of Alzheimers-Disease. Neuron 1989, 3, 519–526.

- Hampel, H.; Blennow, K.; Shaw, L.M.; Hoessler, Y.C.; Zetterberg, H.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Total and phosphorylated tau protein as biological markers of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 30–40.

- McMillan, P.; Korvatska, E.; Poorkaj, P.; Evstafjeva, Z.; Robinson, L.; Greenup, L.; Leverenz, J.; Schellenberg, G.D.; D’Souza, I. Tau Isoform Regulation Is Region- and Cell-Specific in Mouse Brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008, 511, 788–803.

- Liu, C.; Götz, J. Profiling murine tau with 0N, 1N and 2N isoform-specific antibodies in brain and peripheral organs reveals distinct subcellular localization, with the 1N isoform being enriched in the nucleus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84849.

- Roberson, E.D.; Scearce-Levie, K.; Palop, J.J.; Yan, F.; Cheng, I.H.; Wu, T.; Gerstein, H.; Yu, G.-Q.; Mucke, L. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid ß-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science 2007, 316, 750–754.

- Wegmann, S.; Maury, E.A.; Kirk, M.J.; Saqran, L.; Roe, A.; DeVos, S.L.; Nicholls, S.; Fan, Z.; Takeda, S.; Cagsal-Getkin, O. Removing endogenous tau does not prevent tau propagation yet reduces its neurotoxicity. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 3028–3041.

- Sabbagh, J.J.; Kinney, J.W.; Cummings, J.L. Animal systems in the development of treatments for Alzheimer’s disease: Challenges, methods, and implications. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 169–183.

- Mullane, K.; Williams, M. Alzheimer’s therapeutics: Continued clinical failures question the validity of the amyloid hypothesis-but what lies beyond? Biochem. Pharm. 2013, 85, 289–305.

- Allen, B.; Ingram, E.; Takao, M.; Smith, M.J.; Jakes, R.; Virdee, K.; Yoshida, H.; Holzer, M.; Craxton, M.; Emson, P.C. Abundant tau filaments and nonapoptotic neurodegeneration in transgenic mice expressing human P301S tau protein. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 9340–9351.

- Förstl, H.; Kurz, A. Clinical features of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1999, 249, 288–290.

- Perel, P.; Roberts, I.; Sena, E.; Wheble, P.; Briscoe, C.; Sandercock, P.; Macleod, M.; Mignini, L.E.; Jayaram, P.; Khan, K.S. Comparison of treatment effects between animal experiments and clinical trials: Systematic review. Br. Med. J. 2007, 334, 197–200.

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Extrapolating from Animals to Humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 151ps15.

- Holmes, C.; Boche, D.; Wilkinson, D.; Yadegarfar, G.; Hopkins, V.; Bayer, A.; Jones, R.W.; Bullock, R.; Love, S.; Neal, J.W.; et al. Long-term effects of A beta(42) immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: Follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 216–223.

- Gilman, S.; Koller, M.; Black, R.S.; Jenkins, L.; Griffith, S.G.; Fox, N.C.; Eisner, L.; Kirby, L.; Rovira, M.B.; Forette, F.; et al. Clinical effects of A beta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology 2005, 64, 1553–1562.

- Bard, F.; Cannon, C.; Barbour, R.; Burke, R.L.; Games, D.; Grajeda, H.; Guido, T.; Hu, K.; Huang, J.P.; Johnson-Wood, K.; et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 916–919.

- Dodart, J.C.; Bales, K.R.; Gannon, K.S.; Greene, S.J.; DeMattos, R.B.; Mathis, C.; DeLong, C.A.; Wu, S.; Wu, X.; Holtzman, D.M.; et al. Immunization reverses memory deficits without reducing brain A beta burden in Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 452–457.

- Salloway, S.P.; Black, R.; Sperling, R.; Fox, N.; Gilman, S.; Schenk, D.; Grundman, M. A Phase 2 Multiple Ascending Dose Trial of Bapineuzumab in Mild to Moderate Alzheimer Disease Reply. Neurology 2010, 74, 2026–2027.

- Farlow, M.; Amold, S.E.; van Dyck, C.H.; Aisen, P.S.; Snider, B.J.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Friedrich, S.; Dean, R.A.; Gonzales, C.; Sethuraman, G.; et al. Safety and biomarker effects of Solanezumab in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2012, 8, 261–271.

- Doody, R.S.; Thomas, R.G.; Farlow, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Vellas, B.; Joffe, S.; Kieburtz, K.; Raman, R.; Sun, X.Y.; Aisen, P.S.; et al. Phase 3 Trials of Solanezumab for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 311–321.

- Abyadeh, M.; Gupta, V.; Gupta, V.; Chitranshi, N.; Wu, Y.; Amirkhani, A.; Meyfour, A.; Sheriff, S.; Shen, T.; Dhiman, K. Comparative Analysis of Aducanumab, Zagotenemab and Pioglitazone as Targeted Treatment Strategies for Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2022, 12, 1964–1976.

- Holtzman, D.M.; Bales, K.R.; Tenkova, T.; Fagan, A.M.; Parsadanian, M.; Sartorius, L.J.; Mackey, B.; Olney, J.; McKeel, D.; Wozniak, D. Apolipoprotein E isoform-dependent amyloid deposition and neuritic degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 2892–2897.

- Jay, T.R.; Hirsch, A.M.; Broihier, M.L.; Miller, C.M.; Neilson, L.E.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Lamb, B.T.; Landreth, G.E. Disease progression-dependent effects of TREM2 deficiency in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 637–647.

- Lewandowski, C.T.; Weng, J.M.; LaDu, M.J. Alzheimer’s disease pathology in APOE transgenic mouse models: The Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 139, 104811.

- Do Carmo, S.; Cuello, A.C. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic rats. Mol. Neurodegener 2013, 8, 37.

- Lin, J.H. Species similarities and differences in pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1995, 23, 1008–1021.

- Jacob, H.J.; Kwitek, A.E. Rat genetics: Attachign physiology and pharmacology to the genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 33–42.

- Echeverria, V.; Ducatenzeiler, A.; Alhonen, L.; Janne, J.; Grant, S.M.; Wandosell, F.; Muro, A.; Baralle, F.; Li, H.S.; Duff, K.; et al. Rat transgenic models with a phenotype of intracellular A beta accumulation in hippocampus and cortex. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2004, 6, 209–219.

- Leon, W.C.; Canneva, F.; Partridge, V.; Allard, S.; Ferretti, M.T.; DeWilde, A.; Vercauteren, F.; Atifeh, R.; Ducatenzeiler, A.; Klein, W. A novel transgenic rat model with a full Alzheimer’s-like amyloid pathology displays pre-plaque intracellular amyloid-β-associated cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 20, 113–126.

- Flood, D.G.; Lin, Y.-G.; Lang, D.M.; Trusko, S.P.; Hirsch, J.D.; Savage, M.J.; Scott, R.W.; Howland, D.S. A transgenic rat model of Alzheimer’s disease with extracellular Aβ deposition. Neurobiol. Aging 2009, 30, 1078–1090.

- Cohen, R.M.; Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Weitz, T.M.; Rentsendorj, A.; Gate, D.; Spivak, I.; Bholat, Y.; Vasilevko, V.; Glabe, C.G.; Breunig, J.J.; et al. A Transgenic Alzheimer Rat with Plaques, Tau Pathology, Behavioral Impairment, Oligomeric A beta, and Frank Neuronal Loss. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 6245–6256.

- Hanes, J.; Zilka, N.; Bartkova, M.; Caletkova, M.; Dobrota, D.; Novak, M. Rat tau proteome consists of six tau isoforms: Implication for animal models of human tauopathies. J. Neurochem. 2009, 108, 1167–1176.

- Kosik, K.S.; Orecchio, L.D.; Bakalis, S.; Neve, R.L. Developmentally regulated expression of specific tau sequences. Neuron 1989, 2, 1389–1397.

- Filipcik, P.; Zilka, N.; Bugos, O.; Kucerak, J.; Koson, P.; Novak, P.; Novak, M. First transgenic rat model developing progressive cortical neurofibrillary tangles. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1448–1456.

- Koson, P.; Zilka, N.; Kovac, A.; Kovacech, B.; Korenova, M.; Filipcik, P.; Novak, M. Truncated tau expression levels determine life span of a rat model of tauopathy without causing neuronal loss or correlating with terminal neurofibrillary tangle load. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 239–246.

- Hrnkova, M.; Zilka, N.; Minichova, Z.; Koson, P.; Novak, M. Neurodegeneration caused by expression of human truncated tau leads to progressive neurobehavioural impairment in transgenic rats. Brain Res. 2007, 1130, 206–213.

- Aigner, B.; Renner, S.; Kessler, B.; Klymiuk, N.; Kurome, M.; Wunsch, A.; Wolf, E. Transgenic pigs as models for translational biomedical research. J. Mol. Med. 2010, 88, 653–664.

- Luo, Y.L.; Lin, L.; Bolund, L.; Jensen, T.G.; Sorensen, C.B. Genetically modified pigs for biomedical research. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2012, 35, 695–713.

- Jacobsen, J.C.; Bawden, C.S.; Rudiger, S.R.; McLaughlan, C.J.; Reid, S.J.; Waldvogel, H.J.; MacDonald, M.E.; Gusella, J.F.; Walker, S.K.; Kelly, J.M. An ovine transgenic Huntington’s disease model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, ddq063.

- Johnstone, E.; Chaney, M.; Norris, F.; Pascual, R.; Little, S. Conservation of the sequence of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid peptide in dog, polar bear and five other mammals by cross-species polymerase chain reaction analysis. Mol. Brain Res. 1991, 10, 299–305.

- Reid, S.J.; Mckean, N.E.; Henty, K.; Portelius, E.; Blennow, K.; Rudiger, S.R.; Bawden, C.S.; Handley, R.R.; Verma, P.J.; Faull, R.L. Alzheimer’s disease markers in the aged sheep (Ovis aries). Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 58, 112–119.

- Papaioannou, N.; Tooten, P.C.; van Ederen, A.M.; Bohl, J.R.; Rofina, J.; Tsangaris, T.; Gruys, E. Immunohistochemical investigation of the brain of aged dogs. I. Detection of neurofibrillary tangles and of 4-hydroxynonenal protein, an oxidative damage product, in senile plaques. Amyloid 2001, 8, 11–21.

- Rosen, R.F.; Farberg, A.S.; Gearing, M.; Dooyema, J.; Long, P.M.; Anderson, D.C.; Davis-Turak, J.; Coppola, G.; Geschwind, D.H.; Pare, J.F.; et al. Tauopathy with paired helical filaments in an aged chimpanzee. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008, 509, 259–270.

- Gearing, M.; Rebeck, G.W.; Hyman, B.T.; Tigges, J.; Mirra, S.S. Neuropathology and apolipoprotein E profile of aged chimpanzees: Implications for Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 9382–9386.

- Gearing, M.; Tigges, J.; Mori, H.; Mirra, S. β-Amyloid (Aβ) deposition in the brains of aged orangutans. Neurobiol. Aging 1997, 18, 139–146.

- Kimura, N.; Nakamura, S.; Goto, N.; Narushima, E.; Hara, I.; Shichiri, S.; Saitou, K.; Nose, M.; Hayashi, T.; Kawamura, S.; et al. Senile plaques in an aged Western lowland gorilla. Exp. Anim. Tokyo 2001, 50, 77–81.

- Perez, S.E.; Raghanti, M.A.; Hof, P.R.; Kramer, L.; Ikonomovic, M.D.; Lacor, P.N.; Erwin, J.M.; Sherwood, C.C.; Mufson, E.J. Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the neocortex and hippocampus of the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). J. Comp. Neurol. 2013, 521, 4318–4338.

- Perez, S.E.; Sherwood, C.C.; Cranfield, M.R.; Erwin, J.M.; Mudakikwa, A.; Hof, P.R.; Mufson, E.J. Early Alzheimer’s disease–type pathology in the frontal cortex of wild mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei). Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 39, 195–201.

- Nakamura, S.; Kiatipattanasakul, W.; Nakayama, H.; Ono, F.; Sakakibara, I.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Goto, N.; Doi, K. Immunohistochemical characteristics of the constituents of senile plaques and amyloid angiopathy in aged cynomolgus monkeys. J. Med. Primatol. 1996, 25, 294–300.

- Darusman, H.S.; Gjedde, A.; Sajuthi, D.; Schapiro, S.J.; Kalliokoski, O.; Kristianingrum, Y.P.; Handaryani, E.; Hau, J. Amyloid Beta1–42 and the Phoshorylated Tau Threonine 231 in Brains of Aged Cynomolgus Monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 313.

- Nakamura, S.i.; Nakayama, H.; Goto, N.; Ono, F.; Sakakibara, I.; Yoshikawa, Y. Histopathological studies of senile plaques and cerebral amyloidosis in cynomolgus monkeys. J. Med. Primatol. 1998, 27, 244–252.

- Nakamura, S.; Kimura, N.; Nishimura, M.; Torii, R.; Terao, K. Neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in aged cynomolgus monkeys. In Proceedings of the AFLAS and CALAS, Kyoto, Japan, 20–22 September 2008.

- Wisniewski, H.M.; Ghetti, B.; Terry, R.D. Neuritic Senile Plaques and Filamentous Changes in Aged Rhesus-Monkeys. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1973, 32, 566–584.

- Paspalas, C.D.; Carlyle, B.C.; Leslie, S.; Preuss, T.M.; Crimins, J.L.; Huttner, A.J.; van Dyck, C.H.; Rosene, D.L.; Nairn, A.C.; Arnsten, A.F. The aged rhesus macaque manifests Braak stage III/IV Alzheimer’s-like pathology. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 680–691.

- Toledano, A.; Álvarez, M.; López-Rodríguez, A.; Toledano-Díaz, A.; Fernández-Verdecia, C. Does Alzheimer disease exist in all primates? Alzheimer pathology in non-human primates and its pathophysiological implications (II). Neurología 2014, 29, 42–55.

- Latimer, C.S.; Shively, C.A.; Keene, C.D.; Jorgensen, M.J.; Andrews, R.N.; Register, T.C.; Montine, T.J.; Wilson, A.M.; Neth, B.J.; Mintz, A. A nonhuman primate model of early Alzheimer’s disease pathologic change: Implications for disease pathogenesis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 15, 93–105.

- Ndung’u, M.; Hartig, W.; Wegner, F.; Mwenda, J.M.; Low, R.W.C.; Akinyemi, R.O.; Kalaria, R.N. Cerebral amyloid beta(42) deposits and microvascular pathology in ageing baboons. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurol. 2012, 38, 487–499.

- Schultz, C.; Dehghani, F.; Hubbard, G.B.; Thal, D.R.; Struckhoff, G.; Braak, E.; Braak, H. Filamentous tau pathology in nerve cells, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes of aged baboons. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2000, 59, 39–52.

- Schultz, C.; Hubbard, G.B.; Rub, U.; Braak, E.; Braak, H. Age-related progression of tau pathology in brains of baboons. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 905–912.

- Lemere, C.A.; Oh, J.; Stanish, H.A.; Peng, Y.; Pepivani, I.; Fagan, A.M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Westmoreland, S.V.; Mansfield, K.G. Cerebral amyloid-beta protein accumulation with aging in cotton-top tamarins: A model of early Alzheimer’s disease? Rejuvenation Res. 2008, 11, 321–332.

- Giannakopoulos, P.; Silhol, S.; Jallageas, V.; Mallet, J.; Bons, N.; Bouras, C.; Delaere, P. Quantitative analysis of tau protein-immunoreactive accumulations and β amyloid protein deposits in the cerebral cortex of the mouse lemur, Microcebus murinus. Acta Neuropathol. 1997, 94, 131–139.

- Kraska, A.; Dorieux, O.; Picq, J.-L.; Petit, F.; Bourrin, E.; Chenu, E.; Volk, A.; Perret, M.; Hantraye, P.; Mestre-Frances, N. Age-associated cerebral atrophy in mouse lemur primates. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 894–906.

- Mestre, N.; Bons, N. Age-related cytological changes and neuronal loss in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in Microcebus murinus (Lemurian primate). Neurodegeneration 1993, 2, 25–32.

- Geula, C.; Nagykery, N.; Wu, C.-K. Amyloid-β deposits in the cerebral cortex of the aged common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus): Incidence and chemical composition. Acta Neuropathol. 2002, 103, 48–58.

- Rodriguez-Callejas, J.D.; Fuchs, E.; Perez-Cruz, C. Evidence of tau hyperphosphorylation and dystrophic microglia in the common marmoset. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 315.

- Elfenbein, H.A.; Rosen, R.F.; Stephens, S.L.; Switzer, R.C.; Smith, Y.; Pare, J.; Mehta, P.D.; Warzok, R.; Walker, L.C. Cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy in aged squirrel monkeys. Histol. Histopathol. 2007, 22, 155–167.

- Walker, L.; Masters, C.; Beyreuther, K.; Price, D. Amyloid in the brains of aged squirrel monkeys. Acta Neuropathol. 1990, 80, 381–387.

- Smith, D.; Chen, X.; Nonaka, M.; Trojanowski, J.; Lee, V.-Y.; Saatman, K.; Leoni, M.; Xu, B.; Wolf, J.; Meaney, D. Accumulation of amyloid β and tau and the formation of neurofilament inclusions following diffuse brain injury in the pig. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1999, 58, 982–992.

- Braak, H.; Braak, E.; Strothjohann, M. Abnormally phosphorylated tau protein related to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads in the cerebral cortex of sheep and goat. Neurosci. Lett. 1994, 171, 1–4.

- Nelson, P.; Saper, C. Ultrastructure of neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex of sheep. Neurobiol. Aging 1995, 16, 315–323.

- Nelson, P.T.; Greenberg, S.G.; Saper, C.B. Neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex of sheep. Neurosci. Lett. 1994, 170, 187–190.

- Nakamura, S.-I.; Nakayama, H.; Uetsuka, K.; Sasaki, N.; Uchida, K.; Goto, N. Senile plaques in an aged two-humped (Bactrian) camel (Camelus bactrianus). Acta Neuropathol. 1995, 90, 415–418.

- Härtig, W.; Klein, C.; Brauer, K.; Schüppel, K.-F.; Arendt, T.; Brückner, G.; Bigl, V. Abnormally phosphorylated protein tau in the cortex of aged individuals of various mammalian orders. Acta Neuropathol. 2000, 100, 305–312.

- Colle, M.-A.; Hauw, J.-J.; Crespeau, F.; Uchihara, T.; Akiyama, H.; Checler, F.; Pageat, P.; Duykaerts, C. Vascular and parenchymal Aβ deposition in the aging dog: Correlation with behavior. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 695–704.

- Yu, C.H.; Song, G.S.; Yhee, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Im, K.S.; Nho, W.G.; Lee, J.H.; Sur, J.H. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Comparison of the Brain of Human Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and the Brain of Aged Dogs with Cognitive Dysfunction. J. Comp. Pathol. 2011, 145, 45–58.

- Abey, A.; Davies, D.; Goldsbury, C.; Buckland, M.; Valenzuela, M.; Duncan, T. Distribution of tau hyperphosphorylation in canine dementia resembles early Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 2021, 31, 144–162.

- Ozawa, M.; Chambers, J.K.; Uchida, K.; Nakayama, H. The Relation between canine cognitive dysfunction and age-related brain lesions. J. Vet. Med Sci. 2016, 78, 991–1006.

- Schmidt, F.; Boltze, J.; Jäger, C.; Hofmann, S.; Willems, N.; Seeger, J.; Härtig, W.; Stolzing, A. Detection and quantification of β-amyloid, pyroglutamyl Aβ, and tau in aged canines. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2015, 74, 912–923.

- Smolek, T.; Madari, A.; Farbakova, J.; Kandrac, O.; Jadhav, S.; Cente, M.; Brezovakova, V.; Novak, M.; Zilka, N. Tau hyperphosphorylation in synaptosomes and neuroinflammation are associated with canine cognitive impairment. J. Comp. Neurol. 2016, 524, 874–895.

- Fiock, K.L.; Smith, J.D.; Crary, J.F.; Hefti, M.M. β-amyloid and tau pathology in the aging feline brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2020, 528, 112–117.

- Sordo Sordo, L. Neuropathology, Diagnosis, and Potential Treatment of Feline Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome and Its Similarities to Alzheimer’s Disease; University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2021.

- Chambers, J.K.; Uchida, K.; Harada, T.; Tsuboi, M.; Sato, M.; Kubo, M.; Kawaguchi, H.; Miyoshi, N.; Tsujimoto, H.; Nakayama, H. Neurofibrillary tangles and the deposition of a beta amyloid peptide with a novel N-terminal epitope in the brains of wild Tsushima leopard cats. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46452.

- Cork, L.C.; Powers, R.E.; Selkoe, D.J.; Davies, P.; Geyer, J.J.; Price, D.L. Neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in aged bears. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1988, 47, 629–641.

- Uchida, K.; Yoshino, T.; Yamaguchi, R.; Tateyama, S.; Kimoto, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Goto, N. Senile plaques and other senile changes in the brain of an aged American black bear. Vet. Pathol. 1995, 32, 412–414.

- Roertgen, K.E.; Parisi, J.E.; Clark, H.B.; Barnes, D.L.; O’Brien, T.D.; Johnson, K.H. Aβ-associated cerebral angiopathy and senile plaques with neurofibrillary tangles and cerebral hemorrhage in an aged wolverine (Gulo gulo). Neurobiol. Aging 1996, 17, 243–247.

- Takaichi, Y.; Chambers, J.K.; Takahashi, K.; Soeda, Y.; Koike, R.; Katsumata, E.; Kita, C.; Matsuda, F.; Haritani, M.; Takashima, A. Amyloid β and tau pathology in brains of aged pinniped species (sea lion, seal, and walrus). Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2021, 9, 1–15.

- Finch, C.E. Evolution of the human lifespan and diseases of aging: Roles of infection, inflammation, and nutrition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1718–1724.

- Knight, A. The beginning of the end for chimpanzee experiments? Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 2008, 3, 1–14.

- Shumaker, R.W.; Wich, S.A.; Perkins, L. Reproductive life history traits of female orangutans (Pongo spp.). In Primate Reproductive Aging; Karger Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2008; Volume 36, pp. 147–161.

- Nishida, T.; Corp, N.; Hamai, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Hiraiwa-Hasegawa, M.; Hosaka, K.; Hunt, K.D.; Itoh, N.; Kawanaka, K.; Matsumoto-Oda, A. Demography, female life history, and reproductive profiles among the chimpanzees of Mahale. Am. J. Primatol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Primatol. 2003, 59, 99–121.

- Li, H.W.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C. Current state of research on non-human primate models of Alzheimer’s disease. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2019, 2, 227–238.

- Uno, H. Age-related pathology and biosenescent markers in captive rhesus macaques. Age 1997, 20, 1–13.

- Souder, D.C.; Dreischmeier, I.A.; Smith, A.B.; Wright, S.; Martin, S.A.; Sagar, M.A.K.; Eliceiri, K.W.; Salamat, S.M.; Bendlin, B.B.; Colman, R.J. Rhesus monkeys as a translational model for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13374.

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991, 82, 239–259.

- Picq, J.-L. Aging affects executive functions and memory in mouse lemur primates. Exp. Gerontol. 2007, 42, 223–232.

- Mestre-Francés, N.; Trouche, S.G.; Fontes, P.; Lautier, C.; Devau, G.; Lasbleiz, C.; Dhenain, M.; Verdier, J.-M. Old Gray Mouse Lemur Behavior, Cognition, and Neuropathology. In Conn’s Handbook of Models for Human Aging; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 287–300.

- Bons, N.; Mestre, N.; Petter, A. Senile plaques and neurofibrillary changes in the brain of an aged lemurian primate, Microcebus murinus. Neurobiol. Aging 1992, 13, 99–105.

- Bons, N.; Mestre, N.; Ritchie, K.; Petter, A.; Podlisny, M.; Selkoe, D. Identification of Amyloid-Beta Protein in the Brain of the Small, Short-Lived Lemurian Primate Microcebus-Murinus. Neurobiol. Aging 1994, 15, 215–220.

- Bons, N.; Rieger, F.; Prudhomme, D.; Fisher, A.; Krause, K.H. Microcebus murinus: A useful primate model for human cerebral aging and Alzheimer’s disease? Genes Brain Behav. 2006, 5, 120–130.

- Dhenain, M.; Chenu, E.; Hisley, C.K.; Aujard, F.; Volk, A. Regional atrophy in the brain of lissencephalic mouse lemur primates: Measurement by automatic histogram-based segmentation of MR images. Magn. Reson. Med. Off. J. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 2003, 50, 984–992.

- Okano, H.; Hikishima, K.; Iriki, A.; Sasaki, E. The common marmoset as a novel animal model system for biomedical and neuroscience research applications. In Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 336–340.

- King, A. The search for better animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2018, 559, S13.

- Ramirez, M.; Ridley, R.; Baker, H.; Maclean, C.; Honer, W.; Francis, P. Chronic elevation of amyloid precursor protein in the neocortex or hippocampus of marmosets with selective cholinergic lesions. J. Neural Transm. 2001, 108, 809–826.

- Trouche, S.G.; Asuni, A.; Rouland, S.; Wisniewski, T.; Frangione, B.; Verdier, J.-M.; Sigurdsson, E.M.; Mestre-Francés, N. Antibody response and plasma Aβ1-40 levels in young Microcebus murinus primates immunized with Aβ1-42 and its derivatives. Vaccine 2009, 27, 957–964.

- Seneca, N.; Cai, L.; Liow, J.-S.; Zoghbi, S.S.; Gladding, R.L.; Hong, J.; Pike, V.W.; Innis, R.B. Brain and whole-body imaging in nonhuman primates with MeS-IMPY, a candidate radioligand for β-amyloid plaques. Nuclear Med. Biol. 2007, 34, 681–689.

- Liang, S.H.; Holland, J.P.; Stephenson, N.A.; Kassenbrock, A.; Rotstein, B.H.; Daignault, C.P.; Lewis, R.; Collier, L.; Hooker, J.M.; Vasdev, N. PET neuroimaging studies of CABS13 in a double transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease and nonhuman primates. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 535–541.

- Heuer, E.; Jacobs, J.; Du, R.; Wang, S.; Keifer, O.P.; Cintron, A.F.; Dooyema, J.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Walker, L.C. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in an Aged Squirrel Monkey with Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 57, 519–530.

- Stöhr, J.; Watts, J.C.; Mensinger, Z.L.; Oehler, A.; Grillo, S.K.; DeArmond, S.J.; Prusiner, S.B.; Giles, K. Purified and synthetic Alzheimer’s amyloid beta (Aβ) prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11025–11030.

- Goedert, M. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: The prion concept in relation to assembled Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. Science 2015, 349.

- Ridley, R.; Baker, H.; Windle, C.; Cummings, R. Very long term studies of the seeding of β-amyloidosis in primates. J. Neural Transm. 2006, 113, 1243–1251.

- Beckman, D.; Morrison, J.H. Towards developing a rhesus monkey model of early Alzheimer’s disease focusing on women’s health. Am. J. Primatol. 2021, e23289.

- Forny-Germano, L.; e Silva, N.M.L.; Batista, A.F.; Brito-Moreira, J.; Gralle, M.; Boehnke, S.E.; Coe, B.C.; Lablans, A.; Marques, S.A.; Martinez, A.M.B. Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology induced by amyloid-β oligomers in nonhuman primates. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 13629–13643.

- Beckman, D.; Chakrabarty, P.; Ott, S.; Dao, A.; Zhou, E.; Janssen, W.G.; Donis-Cox, K.; Muller, S.; Kordower, J.H.; Morrison, J.H. A novel tau-based rhesus monkey model of Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 933–945.

- Seita, Y.; Morimura, T.; Watanabe, N.; Iwatani, C.; Tsuchiya, H.; Nakamura, S.; Suzuki, T.; Yanagisawa, D.; Tsukiyama, T.; Nakaya, M. Generation of transgenic cynomolgus monkeys overexpressing the gene for Amyloid-β precursor protein. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 75, 45–60.

- Sato, K.; Sasaguri, H.; Kumita, W.; Inoue, T.; Kurosaki, Y.; Nagata, K.; Mihira, N.; Sato, K.; Sakuma, T.; Yamamoto, T. A non-human primate model of familial Alzheimer’s disease. bioRxiv 2020.

- Zeiss, C.J. Utility of spontaneous animal models of Alzheimer’s disease in preclinical efficacy studies. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 380, 273–286.

- Bosch, M.N.; Pugliese, M.; Gimeno-Bayon, J.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Mahy, N. Dogs with Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome: A Natural Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2012, 9, 298–314.

- Head, E. Brain aging in dogs: Parallels with human brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Vet. Ther. 2001, 2, 247–260.

- Head, E. A canine model of human aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2013, 1832, 1384–1389.

- Prpar Mihevc, S.; Majdič, G. Canine Cognitive Dysfunction and Alzheimer’s Disease–Two Facets of the Same Disease? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 604.

- Insua, D.; Suárez, M.-L.; Santamarina, G.; Sarasa, M.; Pesini, P. Dogs with canine counterpart of Alzheimer’s disease lose noradrenergic neurons. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 625–635.

- Neilson, J.C.; Hart, B.L.; Cliff, K.D.; Ruehl, W.W. Prevalence of behavioral changes associated with age-related cognitive impairment in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 1787–1791.

- Salvin, H.E.; McGreevy, P.D.; Sachdev, P.S.; Valenzuela, M.J. The canine cognitive dysfunction rating scale (CCDR): A data-driven and ecologically relevant assessment tool. Vet. J. 2011, 188, 331–336.

- Madari, A.; Farbakova, J.; Katina, S.; Smolek, T.; Novak, P.; Weissova, T.; Novak, M.; Zilka, N. Assessment of severity and progression of canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome using the CAnine DEmentia Scale (CADES). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 171, 138–145.

- Osella, M.; Re, G.; Odore, R.; Girardi, C.; Badino, P.; Barbero, R.; Bergamasco, L. Canine Cognitive Dysfunction: Prevalence, Clinical Signs and Treatment with a Nutraceutical; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2005; pp. 66–72.

- Wisniewski, H.; Johnson, A.; Raine, C.; Kay, W.; Terry, R. Senile plaques and cerebral amyloidosis in aged dogs. A histochemical and ultrastructural study. Lab. Investig. 1970, 23, 287–296.

- Pugliese, M.; Geloso, M.C.; Carrasco, J.L.; Mascort, J.; Michetti, F.; Mahy, N. Canine cognitive deficit correlates with diffuse plaque maturation and S100β (−) astrocytosis but not with insulin cerebrospinal fluid level. Acta Neuropathol. 2006, 111, 519.

- Butterfield, D.A.; Barone, E.; Di Domenico, F.; Cenini, G.; Sultana, R.; Murphy, M.P.; Mancuso, C.; Head, E. Atorvastatin treatment in a dog preclinical model of Alzheimer’s disease leads to up-regulation of haem oxygenase-1 and is associated with reduced oxidative stress in brain. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 15, 981–987.

- Barone, E.; Mancuso, C.; Di Domenico, F.; Sultana, R.; Murphy, M.P.; Head, E.; Butterfield, D.A. Biliverdin reductase-A: A novel drug target for atorvastatin in a dog pre-clinical model of Alzheimer disease. J. Neurochem. 2012, 120, 135–146.

- Di Domenico, F.; Perluigi, M.; Barone, E. Biliverdin Reductase-A correlates with inducible nitric oxide synthasein in atorvastatin treated aged canine brain. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 1925.

- Bosch, M.N.; Bayon, J.G.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Pugliese, M.; Mahy, N. Rapid improvement of canine cognitive dysfunction with immunotherapy designed for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2013, 10, 482–493.

- Head, E.; Moffat, K.; Das, P.; Sarsoza, E.; Poon, W.W.; Landsberg, G.; Cotman, C.W.; Murphy, M.P. beta-amyloid deposition and tau phosphorylation in clinically characterized aged cats. Neurobiol. Aging 2005, 26, 749–763.

- Nakamura, S.-i.; Nakayama, H.; Kiatipattanasakul, W.; Uetsuka, K.; Uchida, K.; Goto, N. Senile plaques in very aged cats. Acta Neuropathol. 1996, 91, 437–439.

- Klug, J.; Snyder, J.M.; Darvas, M.; Imai, D.M.; Church, M.; Latimer, C.; Keene, C.D.; Ladiges, W. Aging pet cats develop neuropathology similar to human Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Pathobiol. Ther. 2020, 2, 120–125.

- Sordo, L.; Gunn-Moore, D.A. Cognitive dysfunction in cats: Update on neuropathological and behavioural changes plus clinical management. Vet. Rec. 2021, 188, e3.

- Gunn-Moore, D.; Moffat, K.; Christie, L.A.; Head, E. Cognitive dysfunction and the neurobiology of ageing in cats. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2007, 48, 546–553.

- Perleberg, C.; Kind, A.; Schnieke, A. Genetically engineered pigs as models for human disease. Dis. Models Mech. 2018, 11, dmm030783.

- Prather, R.S.; Lorson, M.; Ross, J.W.; Whyte, J.J.; Walters, E. Genetically engineered pig models for human diseases. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2013, 1, 203–219.

- Walters, E.M.; Agca, Y.; Ganjam, V.; Evans, T. Animal models got you puzzled? Think pig. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1245, 63–64.

- Hoffe, B.; Holahan, M.R. The use of pigs as a translational model for studying neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 838.

- Kragh, P.M.; Nielsen, A.L.; Li, J.; Du, Y.; Lin, L.; Schmidt, M.; Bøgh, I.B.; Holm, I.E.; Jakobsen, J.E.; Johansen, M.G. Hemizygous minipigs produced by random gene insertion and handmade cloning express the Alzheimer’s disease-causing dominant mutation APPsw. Transgenic Res. 2009, 18, 545–558.

- Søndergaard, L.V.; Ladewig, J.; Dagnæs-Hansen, F.; Herskin, M.S.; Holm, I.E. Object recognition as a measure of memory in 1–2 years old transgenic minipigs carrying the APPsw mutation for Alzheimer’s disease. Transgenic Res. 2012, 21, 1341–1348.

- Hall, V.J.; Lindblad, M.M.; Jakobsen, J.E.; Gunnarsson, A.; Schmidt, M.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Volke, D.; Zuchner, T.; Hyttel, P. Impaired APP activity and altered Tau splicing in embryonic stem cell-derived astrocytes obtained from an APPsw transgenic minipig. Dis. Models Mech. 2015, 8, 1265–1278.

- Jakobsen, J.E.; Johansen, M.G.; Schmidt, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Callesen, H.; Melnikova, M.; Habekost, M.; Matrone, C.; Bouter, Y. Expression of the Alzheimer’s disease mutations AβPP695sw and PSEN1M146I in double-transgenic göttingen minipigs. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 53, 1617–1630.

- Weber, K.; Pearce, D.A. Large animal models for Batten disease: A review. J. Child Neurol. 2013, 28, 1123–1127.

- Cook, R.; Jolly, R.; Palmer, D.; Tammen, I.; Broom, M.; McKinnon, R. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in Merino sheep. Aust. Vet. J. 2002, 80, 292–297.

- Jolly, R.; Arthur, D.; Kay, G.; Palmer, D. Neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis in Borderdale sheep. N. Z. Vet. J. 2002, 50, 199–202.

- Jolly, R.; Janmaat, A.; West, D.a.; Morrison, I. Ovine ceroid-lipofuscinosis: A model of Batten’s disease. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurol. 1980, 6, 195–209.

- Kelly, J.M.; Kleemann, D.O.; Walker, S.K. Enhanced efficiency in the production of offspring from 4-to 8-week-old lambs. Theriogenology 2005, 63, 1876–1890.

- Reid, S.J.; Patassini, S.; Handley, R.R.; Rudiger, S.R.; McLaughlan, C.J.; Osmand, A.; Jacobsen, J.C.; Morton, A.J.; Weiss, A.; Waldvogel, H.J. Further molecular characterisation of the OVT73 transgenic sheep model of Huntington’s disease identifies cortical aggregates. J. Huntingt. Dis. 2013, 2, 279–295.

- Handley, R.R.; Reid, S.J.; Brauning, R.; Maclean, P.; Mears, E.R.; Fourie, I.; Patassini, S.; Cooper, G.J.; Rudiger, S.R.; McLaughlan, C.J. Brain urea increase is an early Huntington’s disease pathogenic event observed in a prodromal transgenic sheep model and HD cases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 201711243.

- Pfister, E.L.; DiNardo, N.; Mondo, E.; Borel, F.; Conroy, F.; Fraser, C.; Gernoux, G.; Han, X.; Hu, D.; Johnson, E. Artificial miRNAs reduce human mutant Huntingtin throughout the striatum in a transgenic sheep model of Huntington’s disease. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 663–673.

- Jiang, Y.; Xie, M.; Chen, W.; Talbot, R.; Maddox, J.F.; Faraut, T.; Wu, C.; Muzny, D.M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. The sheep genome illuminates biology of the rumen and lipid metabolism. Science 2014, 344, 1168–1173.

- Kendrick, K.M.; da Costa, A.P.; Leigh, A.E.; Hinton, M.R.; Peirce, J.W. Sheep don’t forget a face. Nature 2001, 414, 165–166.

- Morton, A.J.; Avanzo, L. Executive decision-making in the domestic sheep. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e15752.

- Perentos, N.; Martins, A.Q.; Watson, T.C.; Bartsch, U.; Mitchell, N.L.; Palmer, D.N.; Jones, M.W.; Morton, A.J. Translational neurophysiology in sheep: Measuring sleep and neurological dysfunction in CLN5 Batten disease affected sheep. Brain 2015, 138, 862–874.

- Sawiak, S.J.; Perumal, S.R.; Rudiger, S.R.; Matthews, L.; Mitchell, N.L.; McLaughlan, C.J.; Bawden, C.S.; Palmer, D.N.; Kuchel, T.; Morton, A.J. Rapid and Progressive Regional Brain Atrophy in CLN6 Batten Disease Affected Sheep Measured with Longitudinal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132331.