Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dominic Loske | + 3435 word(s) | 3435 | 2021-12-10 04:48:58 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | Meta information modification | 3435 | 2021-12-16 03:46:06 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Loske, D. Logistics Work, Ergonomics and Social Sustainability. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17145 (accessed on 04 March 2026).

Loske D. Logistics Work, Ergonomics and Social Sustainability. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17145. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Loske, Dominic. "Logistics Work, Ergonomics and Social Sustainability" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17145 (accessed March 04, 2026).

Loske, D. (2021, December 15). Logistics Work, Ergonomics and Social Sustainability. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17145

Loske, Dominic. "Logistics Work, Ergonomics and Social Sustainability." Encyclopedia. Web. 15 December, 2021.

Copy Citation

The methodological basis is a load assessment of the musculoskeletal system in retail intralogistics. Based on the established measurements systems CUELA and OWAS, the specific loads on employees are assessed for four typical logistics workplace settings.

retail logistics

warehousing

ergonomics

health management

1. Introduction

Technology advances are affecting most logistics activities and processes through automatization and digitalization. Examining ergonomics in logistics jobs is warranted due to a high share of manual labor and a direct positive effect on productivity for example in intralogistics: Recent approaches adding the human factor and ergonomics to economic reasoning in warehousing show that quality and performance can be improved [1][2]. This can be connected to the overarching topic of social sustainability addressing working conditions as well as safety and health issues of logistics workers. This implies that the human factor might be highly relevant for increasingly automated and digitalized work systems in logistics. Employee health issues such as physical stress and strain translate to dissatisfaction and reduced commitment to the organization and customers, thus affecting total logistics service quality. Additionally, this extends to workers’ economic welfare and quality of living within the areas of warehousing and intralogistics as investigation examples into learning effects, behavioral issues, energy expenditure, physical effort, fatigue, or other ergonomic indicators show [3]. This paper emphasizes workers’ low back pain issues as it has been established as the prevalent (non-specific) ergonomic issue affecting incapacitation for work for intralogistics professions. This is transferable towards a larger number of logistics jobs, often incorporating physical or driving tasks. Low back pain is non-specific for the majority of cases and can cause disabilities, especially in working-age groups. Even more important for logistics work, people with physically demanding jobs and low socioeconomic status are found as most susceptible to low back pain [4]. For the European Union, four factors outlining workforce health issues, three of which are interesting in the context of this paper—an aging workforce, the growing burden of chronic disease, and widening health inequalities are listed [5]. A current disparity of 1:2 between workers no older than 25 years and workers aged at least 50 years is growing, aggravating the risks of worsening health and withdrawal from the labor market. Health impediments render large parts of the elder population economically inactive already today [6]. Chronic diseases put a burden on the productive capacity of many countries: “For example, 100 million European citizens suffer from chronic musculoskeletal pain and musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), including 40 million workers who attribute their MSD directly to their work” ([4], p. 357). Widening health inequalities play a major role in a vicious circle as for individuals, health is partly determined by income—thus by work and capacity to work. Significant inequality in the labor market extends to distortions in public health as a whole [7] as, for instance, [8] finding positive effects of private insurance on health [9]. This is important as the incentives to keep up workability are increasing for all parties involved.

2. Theoretical Framework for Human Factors in Operations

2.1. General Systems Theory and Human-Technology Interaction

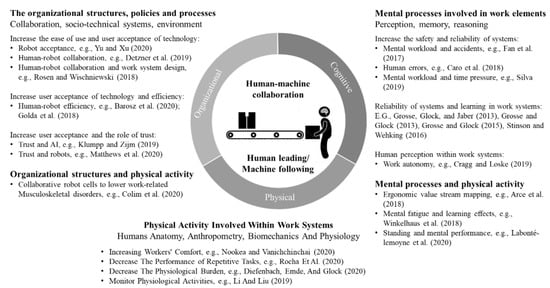

Engineered systems are sociotechnical systems and comprise social and technical elements, see Figure 1 [10]. Human factors (synonymous with ergonomics) as a scientific discipline is concerned with the understanding of the social element within these systems aspiring to optimize human well-being and the overall system performance [11]. This includes investigating the interaction of humans and other elements of a system, as well as planning, developing, applying, and evaluating methodologies that optimize the human well-being and employees’ performance within the system [11]. General systems theory is the theoretical basis for these approaches [12] and sociotechnical systems theory is one subfield within this domain. With the recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics, sociotechnical systems theory has been developed further, leading to the formulation of sociotechnical systems [13] that currently are extended to cyber sociotechnical systems theory [14], in which autonomous and intelligent software (cyber), humans (social), and hardware elements (technical) work jointly to achieve a common goal [15].

Figure 1. Theoretical framework for the human factor in operations processes.

This indicates that the technical element can take various forms, including advanced technologies, e.g., artificial intelligence (human-AI system) and robots (human-robot system), as well as non-advanced technologies, e.g., machines (human-machine system) [16]. Additionally, the interaction may occur in the form of coexistence (shared work time and workspace), cooperation (shared work time, workspace, and work objective), or collaboration (shared work time, workspace, work objective, and work contact) [17]. Furthermore, humans or technical elements may lead this interaction resulting in human leading/technology following or technology leading/human following relationships [18].

To further specify the underlying work task, [19] differentiations between routine tasks that follow a set of rules that can be computerized and non-routine tasks that are, at a certain point in time, not sufficiently well-understood to be computerized and executed by machines [20]. Non-routine tasks are divided further into abstract non-routine tasks that require intuition or creativity, and manual non-routine tasks [21]. This taxonomy is also applicable to picker-to-parts order picking systems and grasping and stacking processes represent a manual non-routine.

In summary, researchers position the empirical research and the contribution to the existing literature within the area of non-advanced human-machine interaction assigned to sociotechnical systems theory as a subfield of general systems theory. Additionally, researchers are concerned with the aspect of collaboration in a human leading/technology following relationship in manual material handling of picker-to-parts order picking systems as a manual non-routine work task.

2.2. The Human Factor in Human-Machine Collaboration

For many years, productions and operations management (OM) was concerned with the optimization of flows and the reduction of bottlenecks by applying methodologies from the domain of operations research [22]. This lead to the development of theories that focus on swift and even material flow while proposing that humans play a subordinate role in the outcome of operations, e.g., the theory of swift and even flow [23]. Although it is possible to automate warehouse processes, for example, human workers’ activities are still required [24].

Therefore, leading scholars claim that human behavior is essential for the understanding of operations [25][26]. Following these calls, researchers can observe the emergence streams incorporating the social aspect of human-technology interaction, e.g., behavioral operations management from an OM perspective [27][28][29] and human factors from an engineering perspective [30][31]. Because behavioral operations management is more concerned with cognitive aspects and resulting decisions of human operators, the empirical research is more associated with the physical ergonomics area of human factors. To foster the understanding for this subfield and further position the contribution, researchers review literature including physical ergonomics and the overlaps towards organizational and cognitive ergonomics. Additionally, the review is directed towards the design of warehouse and picking workplaces, possible measures to mitigate ergonomic issues, and leveraging the burden of logistics workers in warehousing processes as outlined in later sections of this paper.

2.2.1. Organizational Ergonomics

Organizational ergonomics, also commonly referred to as macro-ergonomics, centers on optimizing socio-technical systems and organizational structures, e.g., policies, organizational structures, and processes [32]. The primary goals are to increase the ease of use of new technology, often leading to work system design-related questions and to foster the technology acceptance of blue-collar, as well as white-collar workforces.

Positioned in the research stream regarding the ease of use of new technology, Rosen and Wischniewski elaborate on how to design hybrid work systems using lightweight robots [33]. The analyses reveal that task variability, timing, and method control have a substantial impact on employees’ wellbeing. Stadnicka and Antonelli develop a framework for the collaborative teamwork process between human workers and intelligent machines and propose a concrete redesign of industrial assembly cells [34]. Ender et al. outline a human-centered design solution for industrial workplaces, particularly considering the needs of workforces within human-robot collaboration [35]. Regarding technology acceptance, the question concerning the level of control transferred to machines is relevant, addressing different levels of acceptance and trust in human-computer interaction, as well as the possible danger of an artificial divide at the individual and firm level [36]. Other researchers investigate predictors of trust in an autonomous robot detecting threat on either a physics-based or psychological basis. The results indicate that the negative attitudes toward robots scale are specifically associated with lower psychological trust [37]. Barosz et al. present a simulation-based analysis of productivity in a manufacturing line where machines can be operated by humans or robots [38]. The authors propose to implement a robotic line from an industry based on the results for the overall factory efficiency metric. Yu and Xu review the influencing factors of robot acceptance from three aspects: robot factors, human factors, and human-robot interaction factors [39]. Datzner et al. present a novel task description language for human-robot interaction in warehouse logistics to let human workers interact with robots naturally [40].

Altogether, it can be stated that there are studies addressing the changes for sociotechnical systems and organizational structures through the increasing automation of operational processes. However, the intersection of organizational structures and physical ergonomics is hardly addressed and researchers aspire to contribute to this intersection by empirical and practice-oriented research.

2.2.2. Cognitive Ergonomics

The goal of cognitive ergonomics is to increase the safety and reliability of systems, as well as to decrease fatigue and physical stress. Within the first stream of memory and reasoning of the human workforce, Caro et al. develop a model for the cognitive architecture for a dry foods company’s semi-mechanized order picking operation when aspiring to decrease human errors and, therefore, increase service level [41]. Silva examines the mental workload, tasks, and activities of press operators in a recycling cooperative that works under various time pressures, physical loads, stresses, and tensions [42]. Furthermore, Fan et al. study the mental workload, attention, or fatigue of seafarers and propose to optimize the crew training system based on simulators [43]. A second research field in cognitive ergonomics is human learning within operations systems. Stinson et al. conducted an experimental analysis of manual order picking processes in a learning warehouse [44] and Grosse et al. present an experimental investigation of learning effects in order picking systems at a manufacturer of household products [45]. Further contributions related to learning curves in order picking develop analytical models, simulations, or theoretical frameworks, aiming to describe the process of learning in order picking [46][47][48]. A third research stream in cognitive ergonomics investigates the perception of humans, e.g., the perceived work autonomy of human order pickers in manual man to good order picking systems [49].

In summary, cognitive ergonomics and especially learning processes are well-examined fields in engineering-driven human factor analysis. The intersection of cognitive and physical ergonomics is highly relevant for routine tasks. However, addressing this intersection requires a detailed understanding of physical factors in human-machine collaboration where researchers aspire to contribute to a more solid foundation.

2.2.3. Physical Ergonomics

In manual and labor-intensive blue-collar operations processes, the investigation of physical activity involved within work systems and its impact on human anatomy, anthropometry, biomechanics, and physiology is of specific interest [50]. Therein, the goal of physical ergonomics is to improve the working environment by (1) increasing workers’ comfort, (2) decreasing the negative impacts of repetitive tasks, (3) decreasing the physiological burden, and (4) monitoring physiological activities. As the contribution of physical ergonomics depends on the research perspective, researchers additionally structured the research streams in planning work systems, designing work systems, evaluating work system practices, and the relationship of employee health and performance. Before creating a working system, the planning of work systems is required, which is increasingly done by using digital human models [51]. Although there are only a few contributions in warehouse logistics, e.g., an approach developing a digital human model within a logistics sorting operation system to improve the working efficiency and workers’ comfort [52], the methodology is well developed for production scenarios [53][54][55][56][57][58][59].

Designing the work system in the next step is examined for more than four decades [60][61][62]. Plonka proposes the application of autonomous mobile robots for the automation of transporting trolleys in hospital logistics, aspiring to relieve the human workforce from frequently carrying high loads and performing repetitive tasks [63]. When focusing on the evaluation of practices in work systems, Diefenbach et al. investigate the physiological stress of handling bins on different levels of a tow train wagon by a computational study that proposes an optimal storage plan, which can significantly ease the physiological burden on the workforce [64]. Another research stream within workplace practices in physical ergonomics is represented by studies dealing with wearable sensors for continuous health monitoring, movement analysis, or rehabilitation [65]. After planning and designing the work system or evaluating workplace practices, the relationship of employee health and performance is the last relevant field in the physical-oriented stream of ergonomics. One example is a study examining how to increase picking efficiency and decrease the physiological burden on the workforce by storing products in bins at an appropriate height. The results indicate that bending and tiptoe significantly decreased by 71.3% and 100%, and the efficiency was improved by 15% [66].

Positioned at the overlap of cognitive and physical factors, research streams investigate physiological factors that influence cognitive factors of the human workforce. Researchers address the overlap of cognitive and physical factors when studying the effects of human fatigue on learning in an explorative experimental analysis—findings show that mental fatigue appears to have a negative influence on learning effects [67]. A further example for an investigation positioned at the intersection of cognitive and physical factors is a study to determine if using a standing desk would affect the productivity of workers, based on the type of work they perform. The researchers found out that a standing desk had no negative effect on performance or perception, but it did lead to increased brain activity [68]. Aspiring to merge ergonomics and performance, current research approaches propose the application of ergonomic value stream mapping [69]. At the interface of organizational and physical factors, research streams investigate the impact of automation on physical activity involved within work systems. Other authors claim that work-related musculoskeletal disorders are one of the leading occupational health problems and develop a physical ergonomics framework at an assembly workstation of a large furniture enterprise and derive requirements for the creation of a collaborative robot cell [70]. Similar results are presented by a study applying the concept of overall equipment effectiveness, to find out how to model robotized, and manually operated workstations through computer simulation software [71].

Altogether, researchers identify a research gap for empirical investigations focusing on the aspect of physical ergonomics in retail logistics, especially with a comprehensive perspective on blue-collar workers and routine tasks including order pickers, as well as forklift operators, or industrial truck drivers. Furthermore, measures derived from quantitative analyses, possibly introduced in the context of an operational health management program, are, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, hardly addressed in logistics-oriented scientific contributions. Although performance and quality are discussed as the primary outcomes of operations systems, the contribution lies in quantifying workers’ well-being as a third dimension for sustainable productions and operations systems.

2.2.4. Impact of Low Back Pain

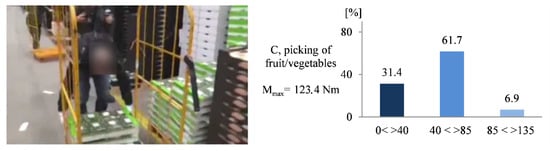

Low back pain is identified as a widespread symptom occurring in countries of all incomes and overall age groups [72][73]. 100 million European citizens have been reported [5][74] to suffer from chronic musculoskeletal pain and musculoskeletal disorders, generally affecting their work performance and to a significant proportion (40 Million) [75] resultant from work activities. In 2015, the prevalence of activity-limiting low back pain was 7.3%, corresponding to 540 million affected people. In 2015, low back pain accounted for 60.1 million lost healthy life years, an increase of 54 million since 1990. [4]. Figure 2 represents typical bowing in warehouse picking leading—among other factors—to such back pain issues as an example, including the torque measures included.

Figure 2. Picking of fruit and corresponding torque in the lumbar spine area (%, Nm).

Most low back pain issues are classified as non-specific, as single-cause explanations are rare. Analogously, the condition affects a range of dimensions (biophysical, psychological, social, social participation, individual finance) and affects both healthcare and social support systems [4][76]. With respect to relatively affluent societies, concerns have been raised regarding the burden of low back pain treatments on healthcare systems [77]. While low back pain is identified by its location, a specific source is usually not identified, and the condition is thus classified as non-specific [78]. Most cases of persistent low back pain are accompanied by pain in other sites, and the prevalence of general health problems, both physical and mental (comorbidity) [79]. A number of potential contributors to this multi-causal condition have been investigated, e.g., intervertebral disc, facet joint, vertebral endplates [80][81][82][83][84]. The rare specific pathological causes include vertebral fracture, axial spondylarthrosis, infections, and malignancy, among others [85][86][87].

As it remains non-specific for the majority of cases, causes disability, especially in working age groups and as people with physically demanding jobs and low socioeconomic status are listed as most susceptible to low back pain [4], examining workplace settings for jobs intensive in manual labor in logistics appear worthwhile. While many physical contributors seem likely, it is essential to note that psychological factors (psychological distress, depression, anxiety) are often present, contribute in ways, which are not fully understood, and merit close investigation and acknowledgment in remedial and preventive activities [88][89]. Instances of treatment methods focusing primarily on beliefs and behaviors rather than direct pain alleviation have been reported for chronic pain treatment before [90]. Also, demographics need consideration, as “low back pain is most prevalent and burdensome in working populations, and in older people low back pain is associated with increased activity limitation” [4], p. 2364.

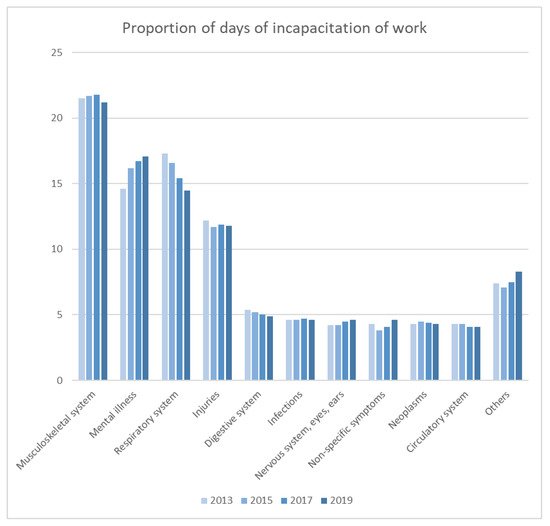

Statistics for Germany (where the study took place) list musculoskeletal pain and mental illness as the top two diagnostic causes of work disability, measured in days away from work (Figure 3) [91].

Figure 3. Causes of incapacitation for work (days of absence, Germany) [91].

Structural and muscular strain, e.g., in the lower back area, can be caused by the handling of heavy weights and prolonged maintenance of static postures. Both pose a major cause for injuries, pain, and related symptoms in logistics and production. Working under such conditions for extended periods is extremely likely to induce back injuries and pain, as studies such as the one by Garg et al. [92] show.

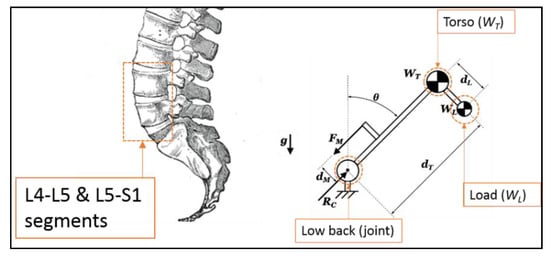

2.3. Low Back Pain and Ergonomics in Retail Operations

A number of activities common to occupations in warehouse logistics and in retail, both inside storage facilities and at the point of sale (e.g., replenishment, retrieval, picking), promote exposure of the lumbar spine (especially L4/L5 & L5/S1; compare, e.g., to compression forces at both unhealthy levels and durations [93]. The high operating cost contribution of warehousing activities [94] has been an incentive for research and optimization efforts into layouts [95], storage assignment [96], and processes such as replenishment and retrieval [97], thus generally aiming at the minimization of travel time and/or distance [98][99]. As long as human workers are involved in warehousing processes such as manual order picking, these objectives need to be characterized as short-term oriented and non-sustainable, as adverse health effects and their cost (e.g., exposure of the lumbar spine to unhealthy levels of compression forces) are either ignored or externalized [100][101] to employees and (public) health insurance. Under time and/or distance objectives, items may be located such that movements and efforts (bending, rotational movements with heavy loads) are imposed on workers who expose, e.g., their spine to hazardous conditions. “Low back disorders, which are the most common type of musculoskeletal disorders, have been shown to occur especially in risk environments where human workers have to move heavy and difficult to handle items in awkward body postures” [102], p. 516—which aptly characterizes the situations observed for the current research.

Figure 4 [103] presents a 2D-model (sagittal plane, right part of Figure 4) exposing the most critical components of forces exerted on the lumbar spine for cases of weight handling with some trunk inclination (e.g., forward bend) [104][105].

Figure 4. Segments of the lumbar spine and compressive loads [103], p. 6.

This is sufficient for a general qualitative understanding of the biomechanics of the lumbar spine during a lifting task, which is, of course, varied and extended, e.g., by rotation in the four activities examined in this paper. It should be noted that considerable lumbar compression forces are generated by the spinal muscles. Compensation of forces generated by loads carried usually requires the spinal muscles to generate large counteracting forces as their closeness to the vertebrae prohibits any considerable leverage. Further, inertial forces add to the load on the lumbar spine (e.g., by rapid movements and rotation) [106]. A detailed description is given in [104]. Here, the lumbar spine is modeled as a rotational joint that connects the torso mass WT to the pelvis. To simplify matters, the pelvis is treated as if attached to the ground. The spinal muscles, responsible for back extension, are not explicit in the figure, but represented by force FM, directed parallel (at distance dM) to the spine. Force RC, reacting at the joint, captures the lumbar compressive loads. The external object (e.g., crates, packages, etc. being carried by workers) is represented by mass WL, rigidly (and perpendicular for simplicity) connected to the upper body.

References

- Gualtieri, L.; Palomba, I.; Merati, F.A.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R. Design of Human-Centered Collaborative Assembly Workstations for the Improvement of Operators’ Physical Ergonomics and Production Efficiency: A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3606.

- Savino, M.M.; Riccio, C.; Menanno, M. Empirical study to explore the impact of ergonomics on workforce scheduling. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 415–433.

- Kong, F. Development of metric method and framework model of integrated complexity evaluations of production process for ergonomics workstations. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2429–2445.

- Hartvigsen, J.; Hancock, M.J.; Kongsted, A.; Louw, Q.; Ferreira, M.L.; Genevay, S.; Hoy, D.; Karppinen, J.; Pransky, G.; Sieper, J.; et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018, 391, 2356–2367.

- Bevan, S. Economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) on work in Europe. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 29, 356–373.

- Schofield, D.J.; Shrestha, R.N.; Passey, M.E.; Earnest, A.; Fletcher, S.L. Chronic disease and labour force participation among older Australians. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 189, 447–450.

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Bell, R.; Bloomer, E.; Goldblatt, P.; Consortium for the European Review of Social Determinants of Health and the Health Divide. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012, 380, 1011–1029.

- Hullegie, P.; Klein, T.J. The effect of private health insurance on medical care utilization and self-assessed health in Germany. Health Econ. 2010, 19, 1048–1062.

- Thomson, S.; Mossialos, E. Choice of public or private health insurance: Learning from the experience of Germany and the Netherlands. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2006, 16, 315–327.

- Neumann, W.P.; Winkelhaus, S.; Grosse, E.H.; Glock, C.H. Industry 4.0 and the human factor—A systems framework and analysis methodology for successful development. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 233, 107992.

- International Ergonomics Association. Human Factors/Ergonomics (HF/E): Definition and Applications. 2021. Available online: https://iea.cc/what-is-ergonomics/#:~:text=Ergonomics%20 (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Skyttner, L. General Systems Theory; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2006.

- Clegg, C.W. Sociotechnical principles for system design. Appl. Ergon. 2000, 31, 463–477.

- Patriarca, R.; Falegnami, A.; Costantino, F.; Di Gravio, G.; De Nicola, A.; Villani, M.L. WAx: An integrated conceptual framework for the analysis of cyber-socio-technical systems. Saf. Sci. 2021, 136, 105142.

- Winkelhaus, S.; Grosse, E.H. Logistics 4.0: A systematic review towards a new logistics system. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 18–43.

- Fragapane, G.; de Koster, R.B.M.; Sgarbossa, F.; Strandhagen, J.O. Planning and control of autonomous mobile robots for intralogistics: Literature review and research agenda. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 405–426.

- Schmidtler, J.; Knott, V.; Hölzel, C.; Bengler, K. Human Centered Assistance Applications for the working environment of the future. Occup. Ergon. 2015, 12, 83–95.

- Pasparakis, A.; de Vries, J.; de Koster, R.B.M. In Control or under Control?: Human-Robot Collaboration in Warehouse Order Picking. SSRN J. 2021.

- Autor, D.H. Why Are There Still So Many Jobs?: The History and Future of Workplace Automation. J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 3–30.

- Deschacht, N. The digital revolution and the labour economics of automation: A review. ROBONOMICS J. Autom. Econ. 2021, 1, 8.

- Autor, D.H.; Levy, F.; Murnane, R.J. The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration. Q. J. Econ. 2003, 118, 1279–1333.

- Lewis, M.A. Operations Management: A Research Overview; Routledge Focus; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Schmenner, R.W.; Swink, M.L. On theory in operations management. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 17, 97–113.

- Lee, J.A.; Chang, Y.S.; Choe, Y.H. Assessment and Comparison of Human-Robot Co-work Order Picking Systems Focused on Ergonomic Factors. In Proceedings of the AHFE 2017 International Conference on Safety Management and Human Factors, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17–21 July 2017; pp. 516–523.

- Gino, F.; Pisano, G.P. Toward a Theory of Behavioral Operations. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2008, 10, 676–691.

- Bendoly, E.; Donohue, K.; Schultz, K.L. Behavior in operations management: Assessing recent findings and revisiting old assumptions. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 737–752.

- Donohue, K.; Özer, Ö.; Zheng, Y. Behavioral Operations: Past, Present, and Future. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2020, 22, 191–202.

- Bendoly, E.; Croson, R.; Goncalves, P.; Schultz, K. Bodies of knowledge for research in behavioral operations. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2010, 19, 434–452.

- Loch, C.H.; Wu, Y. Behavioral Operations Management. Found. Trends Technol. Inf. Oper. Manag. 2005, 1, 121–232.

- Patrick Neumann, W.; Dul, J. Human factors: Spanning the gap between OM and HRM. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2010, 30, 923–950.

- Setayesh, A.; Grosse, E.H.; Glock, C.H.; Neumann, W.P. Determining the source of human-system errors in manual order picking with respect to human factors. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021.

- Bau, L.M.S.; Farias, J.P.; Buso, S.A.; Passero, C.R.M. Organizational ergonomics of occupational health methods and processes in a Brazilian oil refinery. Work 2012, 41 (Suppl. 1), 2817–2821.

- Rosen, P.H.; Wischniewski, S. Task Design in Human-Robot-Interaction Scenarios—Challenges from a Human Factors Perspective. Int. Conf. Hum. Factors Syst. Interact. 2017, 592, 71–82.

- Stadnicka, D.; Antonelli, D. Human-robot collaborative work cell implementation through lean thinking. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2019, 32, 580–595.

- Ender, J.; Wagner, J.C.; Kunert, G.; Larek, R.; Pawletta, T.; Guo, F.B. Design of an Assisting Workplace Cell for Human-Robot Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Interdisciplinary PhD Workshop (IIPhDW), Wismar, Germany, 15–17 May 2019; pp. 51–56.

- Klumpp, M.; Zijm, H. Logistics Innovation and Social Sustainability: How to Prevent an Artificial Divide in Human-Computer Interaction. J. Bus. Logist. 2019, 40, 265–278.

- Matthews, G.; Lin, J.; Panganiban, A.R.; Long, M.D. Individual Differences in Trust in Autonomous Robots: Implications for Transparency. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2020, 50, 234–244.

- Barosz, P.; Gołda, G.; Kampa, A. Efficiency Analysis of Manufacturing Line with Industrial Robots and Human Operators. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2862.

- Yu, F.; Xu, L. Factors that influence robot acceptance. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 496–510.

- Detzner, P.; Kirks, T.; Jost, J. A Novel Task Language for Natural Interaction in Human-Robot Systems for Warehouse Logistics. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Science and Education, Toronto, ON, Canada, 19–21 August 2019; pp. 725–730.

- Caro, M.; Quintana, L.; Castillo, M.J.A.; Zea, C. Cognitive Model of a Semi-Mechanized Picking Operation. Rev. Cienc. Salud 2018, 16, 39.

- Silva, H.R. Analysis of the Mental Workloads Applied to Press Operators during the Reuse and Recycling of Materials. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Human Systems Integration, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–10 February 2019; Volume 903, pp. 673–678.

- Fan, S.; Yan, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J. A review on human factors in maritime transportation using seafarers’ physiological data. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety, Banff, AB, Canada, 8–10 August 2017; pp. 104–110.

- Stinson, M.; Wehking, K.-H. Experimental analysis of manual order picking processes in a Learning Warehouse. Logist. J. Proc. 2016, 2016.

- Grosse, E.H.; Glock, C.H. An experimental investigation of learning effects in order picking systems. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2013, 24, 850–872.

- Grosse, E.H.; Glock, C.H. The effect of worker learning on manual order picking processes. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 170, 882–890.

- Grosse, E.H.; Glock, C.H.; Jaber, M.Y. The effect of worker learning and forgetting on storage reassignment decisions in order picking systems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2013, 66, 653–662.

- Shafer, S.M.; Nembhard, D.A.; Uzumeri, M.V. The Effects of Worker Learning, Forgetting, and Heterogeneity on Assembly Line Productivity. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 1639–1653.

- Cragg, T.; Loske, D. Perceived work autonomy in order picking systems: An empirical analysis. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 1872–1877.

- Drury, C.G. Global quality: Linking ergonomics and production. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2000, 38, 4007–4018.

- Peters, M.; Quadrat, E.; Nolte, A.; Wolf, A.; Miehling, J.; Wartzack, S.; Leidholdt, W.; Bauer, S.; Fritzsche, L.; Wischniewski, S. Biomechanical Digital Human Models: Chances and Challenges to Expand Ergonomic Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Human Systems Engineering and Design, Reims, France, 25–27 October 2018; CHU-Université de Reims Champagne: Ardenne, France; Volume 876, pp. 885–890.

- Li, Y.; Liu, L. Investigation into Ergonomics in Logistics Sorting Equipment. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computation, Communication and Engineering, Fujian, China, 8–10 November 2019; pp. 167–169.

- Chaffin, D.B. Improving digital human modelling for proactive ergonomics in design. Ergonomics 2005, 48, 478–491.

- Chaffin, D.B. Human motion simulation for vehicle and workplace design. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2007, 17, 475–484.

- Jung, K.; Kwon, O.; You, H. Development of a digital human model generation method for ergonomic design in virtual environment. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2009, 39, 744–748.

- Fritzsche, L. Ergonomics risk assessment with digital human models in car assembly: Simulation versus real life. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2010, 20, 287–299.

- Faccio, M.; Ferrari, E.; Gamberi, M.; Pilati, F. Human Factor Analyser for work measurement of manual manufacturing and assembly processes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 103, 861–877.

- Sun, X.; Houssin, R.; Renaud, J.; Gerdoni, M. Towards a human factors and ergonomics integration framework in the early product design phase: Function-Task-Behaviour. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 4941–4953.

- van Lingen, P.; van Rhijn, G.; de Looze, M.; Vink, P.; Koningsveld, G.; Tuinzaad, G.; Leskinen, T. ERGOtool for the integral improvement of ergonomics and process flow in assembly. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2002, 40, 3973–3980.

- Ayoub, M.M. Work place design and posture. Hum. Factors 1973, 15, 265–268.

- Jørgensen, K.; Fallentin, N.; Sidenius, B. The strain on the shoulder and neck muscles during letter sorting. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 1989, 3, 243–248.

- Plonka, F.E. Developing a lean and agile work force. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 1997, 7, 11–20.

- Rocha, C.; Sousa, I.; Ferreira, F.; Sobreira, H.; Lima, L.; Veiga, G.A.; Moreira, P. Development of an Autonomous Mobile Towing Vehicle for Logistic Tasks. In Robot 2019: Fourth Iberian Robotics Conference; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Silva, M., Luís Lima, J., Reis, L., Sanfeliu, A., Tardioli, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1092.

- Diefenbach, H.; Emde, S.; Glock, C.H. Loading tow trains ergonomically for just-in-time part supply. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 284, 325–344.

- Chander, H.; Burch, R.F.; Talegaonkar, P.; Saucier, D.; Luczak, T.; Ball, J.E.; Turner, A.; Kodithuwakka Arachige, S.N.K.; Caroll, W.; Smith, B.K.; et al. Wearable Stretch Sensors for Human Movement Monitoring and Fall Detection in Ergonomics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3554.

- Nookea, W.; Vanichchinchai, A. An Ergonomics-Based Storage Bin Allocation for Picking Efficiency Improvement. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications, Bangkok, Thailand, 16–21 April 2020; pp. 307–310.

- Winkelhaus, S.; Sgarbossa, F.; Calzavara, M.; Grosse, E.H. The effects of human fatigue on learning in order picking: An explorative experimental investigation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 832–837.

- Labonté-LeMoyne, E.; Jutras, M.-A.; Léger, P.-M.; Senecal, S.; Fredette, M.; Begon, M.; Mathieu, M.-E. Does Reducing Sedentarity with Standing Desks Hinder Cognitive Performance? Hum. Factors 2020, 62, 603–612.

- Arce, A.; Romero-Dessens, L.F.; Leon-Duarte, J.A. Ergonomic Value Stream Mapping: A Novel Approach to Reduce Subjective Mental Workload. In Advances in Social & Occupational Ergonomics, Proceedings of the AHFE 2017 International Conference on Social & Occupational Ergonomics, The Westin Bonaventure Hotel, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17–21 July 2017; Goosens, R.H.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 605, pp. 307–317.

- Colim, A.; Faria, C.; Braga, A.C.; Sousa, N.; Rocha, L.; Carneiro, P.; Costa, N.; Arezes, P. Towards an Ergonomic Assessment Framework for Industrial Assembly Workstations—A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3048.

- Gołda, G.; Kampa, A.; Paprocka, I. Analysis of human operators and industrial robots performance and reliability. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2019, 9, 24–33.

- Hoy, D.; Bain, C.; Williams, G.; March, L.; Brooks, P.; Blyth, F.; Woolf, A.; Vos, T.; Buchbinder, R. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 2028–2037.

- Kamper, S.J.; Henschke, N.; Hestbaek, L.; Dunn, K.M.; Williams, C.M. Musculoskeletal pain in children and adolescents. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2016, 20, 275–284.

- Veale, D.J.; Woolf, A.D.; Carr, A.J. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and arthritis: Impact, attitudes and perceptions. Ir. Med. J. 2008, 101, 208–210.

- European Commission. Commission Asks Workers and Employers What Action Should Be Taken to Combat Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2004. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_04_1358 (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Maniadakis, N.; Gray, A. The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain 2000, 84, 95–103.

- Deyo, R.A.; Mirza, S.K.; Turner, J.A.; Brook, I.M. Overtreating chronic back pain: Time to back off? J. Am. Board Fam. Med. JABFM 2009, 22, 62–68.

- Maher, C.; Underwood, M.; Buchbinder, R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2017, 389, 736–747.

- Hartvigsen, J.; Natvig, B.; Ferreira, M. Is it all about a pain in the back? Best practice & research. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 27, 613–623.

- Määttä, J.H.; Karppinen, J.; Paananen, M.; Bow, C.; Luk, K.D.K.; Cheung, K.M.C.; Samartzis, D. Refined Phenotyping of Modic Changes: Imaging Biomarkers of Prolonged Severe Low Back Pain and Disability. Medicine 2016, 95, e3495.

- Brinjikji, W.; Diehn, F.E.; Jarvik, J.G.; Carr, C.M.; Kallmes, D.F.; Murad, M.H.; Luetmer, P.H. MRI Findings of Disc Degeneration are More Prevalent in Adults with Low Back Pain than in Asymptomatic Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2015, 36, 2394–2399.

- Maas, E.T.; Juch, J.N.S.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Groeneweg, J.G.; Kallewaard, J.W.; Koes, B.W.; Verhagen, A.P.; Huygen, F.J.M.; van Tulder, M.W. Systematic review of patient history and physical examination to diagnose chronic low back pain originating from the facet joints. Eur. J. Pain 2017, 21, 403–414.

- Maas, E.T.; Ostelo Raymond, W.J.G.; Niemisto, L.; Jousimaa, J.; Hurri, H.; Malmivaara, A.; van Tulder, M.W. Radiofrequency denervation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015.

- Hancock, M.J.; Maher, C.G.; Latimer, J.; Spindler, M.F.; McAuley, J.H.; Laslett, M.; Bogduk, N. Systematic review of tests to identify the disc, SIJ or facet joint as the source of low back pain. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 1539–1550.

- Schousboe, J.T. Epidemiology of Vertebral Fractures. J. Clin. Densitom. Off. J. Int. Soc. Clin. Densitom. 2016, 19, 8–22.

- Stolwijk, C.; van Onna, M.; Boonen, A.; van Tubergen, A. Global Prevalence of Spondyloarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 1320–1331.

- Lewandrowski, K.-U. Retrospective analysis of accuracy and positive predictive value of preoperative lumbar MRI grading after successful outcome following outpatient endoscopic decompression for lumbar foraminal and lateral recess stenosis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2019, 179, 74–80.

- Campbell, P.; Bishop, A.; Dunn, K.M.; Main, C.J.; Thomas, E.; Foster, N.E. Conceptual overlap of psychological constructs in low back pain. Pain 2013, 154, 1783–1791.

- Lee, H.; Hübscher, M.; Moseley, G.L.; Kamper, S.J.; Traeger, A.C.; Mansell, G.; McAuley, J.H. How does pain lead to disability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies in people with back and neck pain. Pain 2015, 156, 988–997.

- Frost, H.; Klaber Moffett, J.A.; Moser, J.S.; Fairbank, J.C. Randomised controlled trial for evaluation of fitness programme for patients with chronic low back pain. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1995, 310, 151–154.

- Statistika. Number of Incapacitation for Work in Days in Germany by Diagnosis for the Years 2013–2019. 2021. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/77239/umfrage/krankheit---hauptursachen-fuer-arbeitsunfaehigkeit/ (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Garg, A.; Boda, S.; Hegmann, K.T.; Moore, J.S.; Kapellusch, J.M.; Bhoyar, P.; Thiese, M.S.; Merryweather, A.; Deckow-Schaefer, G.; Bloswick, D.; et al. The NIOSH lifting equation and low-back pain, Part 1: Association with low-back pain in the backworks prospective cohort study. Hum. Factors 2014, 56, 6–28.

- Meakin, J.R.; Smith, F.W.; Gilbert, F.J.; Aspden, R.M. The effect of axial load on the sagittal plane curvature of the upright human spine in vivo. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2850–2854.

- Richards, G. Warehouse Management: A Complete Guide to Improving Efficiency and Minimizing Costs in the Modern Warehouse, 3rd ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; New Dehli, India, 2018.

- Mowrey, C.H.; Parikh, P.J. Mixed-width aisle configurations for order picking in distribution centers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 232, 87–97.

- Rao, S.S.; Adil, G.K. Class-based storage with exact S-shaped traversal routeing in low-level picker-to-part systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 4979–4996.

- Petersen, C.G.; Aase, G. A comparison of picking, storage, and routing policies in manual order picking. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2004, 92, 11–19.

- de Koster, R.B.M.; Le-Duc, T.; Roodbergen, K.J. Design and control of warehouse order picking: A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 182, 481–501.

- Yang, P.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, H. Order batch picking optimization under different storage scenarios for e-commerce warehouses. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 136, 101897.

- Ayres, R.U.; Kneese, A.V. Production, Consumption, and Externalities. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 282–297.

- Spash, C. The Development of Environmental Thinking in Economics. Environ. Values 1999, 8, 413–435.

- Glock, C.H.; Grosse, E.H.; Abedinnia, H.; Emde, S. An integrated model to improve ergonomic and economic performance in order picking by rotating pallets. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 516–534.

- Toxiri, S.; Koopman, A.S.; Lazzaroni, M.; Ortiz, J.; Power, V.; de Looze, M.P.; O’Sullivan, L.; Caldwell, D.G. Rationale, Implementation and Evaluation of Assistive Strategies for an Active Back-Support Exoskeleton. Front. Robot. AI 2018, 5, 53.

- Toxiri, S.; Ortiz, J.; Masood, J.; Fernandez, J.; Mateos, L.A.; Caldwell, D.G. A wearable device for reducing spinal loads during lifting tasks: Biomechanics and design concepts. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Zhuhai, China, 6–9 December 2015; pp. 2295–2300.

- Anderson, C.K.; Chaffin, D.B.; Herrin, G.D.; Matthews, L.S. A biomechanical model of the lumbosacral joint during lifting activities. J. Biomech. 1985, 18, 571–584.

- Reeves, N.P.; Cholewicki, J. Modeling the human lumbar spine for assessing spinal loads, stability, and risk of injury. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 31, 73–139.

More

Information

Subjects:

Anthropology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.6K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 Dec 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No