| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cecilia Ambrosi | + 2831 word(s) | 2831 | 2021-12-03 04:43:56 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 2831 | 2021-12-15 02:50:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

Chaperone-usher fimbrial adhesins are powerful weapons against the uropathogens that allow the establishment of urinary tract infections (UTIs). As the antibiotic therapeutic strategy has become less effective in the treatment of uropathogen-related UTIs, the anti-adhesive molecules active against fimbrial adhesins, key determinants of urovirulence, are attractive alternatives. The best-characterized bacterial adhesin is FimH, produced by uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC). Hence, a number of high-affinity mono- and polyvalent mannose-based FimH antagonists, characterized by different bioavailabilities, have been reported. Given that antagonist affinities are firmly associated with the functional heterogeneities of different FimH variants, several FimH inhibitors have been developed using ligand-drug discovery strategies to generate high-affinity molecules for successful anti-adhesion therapy. As clinical trials have shown d-mannose’s efficacy in UTIs prevention, it is supposed that mannosides could be a first-in-class strategy not only for UTIs, but also to combat other Gram-negative bacterial infections.

1. Introduction

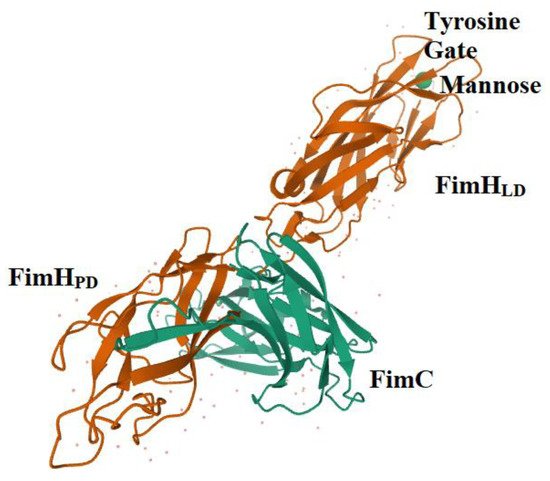

2. FimH is a Highly Adapted Virulence Factor

3. FimH and Glycomimetics

4. FimH Antagonists, Biochemical Characteristics and Bioavailability

References

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: Epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–284.

- Behzadi, P.; Behzadi, E.; Pawlak-Adamska, E.A. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) or genital tract infections (GTIs)? It’s the diagnostics that count. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2019, 14.

- Chockalingam, A.; Stewart, S.; Xu, L.; Gandhi, A.; Matta, M.K.; Patel, V.; Sacks, L.; Rouse, R. Evaluation of immunocompetent urinary tract infected Balb/C mouse model for the study of antibiotic resistance development using Escherichia Coli CFT073 infection. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 170.

- Issakhanian, L.; Behzadi, P. Antimicrobial agents and urinary tract infections. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 1409–1423.

- Behzadi, P. Classical chaperone-usher (CU) adhesive fimbriome: Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2020, 65, 45–65.

- Hozzari, A.; Behzadi, P.; Kerishchi Khiabani, P.; Sholeh, M.; Sabokroo, N. Clinical cases, drug resistance, and virulence genes profiling in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Genet. 2020, 61, 265–273.

- Momtaz, H.; Karimian, A.; Madani, M.; Safarpoor Dehkordi, F.; Ranjbar, R.; Sarshar, M.; Souod, N. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli in Iran: Serogroup distributions, virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance properties. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2013, 12.

- Jahandeh, N.; Ranjbar, R.; Behzadi, P.; Behzadi, E. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence genes: Invaluable approaches for designing DNA microarray probes. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2015, 68, 452–458.

- Behzadi, P.; Najafi, A.; Behzadi, E.; Ranjbar, R. Microarray long oligo probe designing for Escherichia coli: An in-silico DNA marker extraction. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2016, 69, 105–111.

- Scribano, D.; Sarshar, M.; Prezioso, C.; Lucarelli, M.; Angeloni, A.; Zagaglia, C.; Palamara, A.T.; Ambrosi, C. D-Mannose Treatment neither Affects Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Properties nor induces stable fimh modifications. Molecules. 2020, 25, 316.

- Umpiérrez, A.; Scavone, P.; Romanin, D.; Marqués, J.M.; Chabalgoity, J.A.; Rumbo, M.; Zunino, P. Innate immune responses to proteus mirabilis flagellin in the urinary tract. Microbes Infect. 2013, 15, 688–696.

- Behzadi, E.; Behzadi, P. The role of toll-like receptors (TLRs) in urinary tract infections (UTIs). Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2016, 69, 404–410.

- Terlizzi, M.E.; Gribaudo, G.; Maffei, M.E. UroPathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) infections: Virulence factors, bladder responses, antibiotic, and non-antibiotic antimicrobial strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1566.

- Behzadi, P.; Urbán, E.; Matuz, M.; Benkő, R.; Gajdács, M. The role of gram-negative bacteria in urinary tract infections: Current concepts and therapeutic options. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 10.

- Schaffer, J.N.; Pearson, M.M. Proteus mirabilis and urinary tract infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3.

- Wyres, K.L.; Lam, M.; Holt, K.E. Population genomics of klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 344–359.

- Psonis, J.J.; Thanassi, D.G. Therapeutic approaches targeting the assembly and function of chaperone-usher pili. EcoSal Plus 2019, 8.

- Kleeb, S.; Pang, L.; Mayer, K.; Eris, D.; Sigl, A.; Preston, R.C.; Zihlmann, P.; Sharpe, T.; Jakob, R.P.; Abgottspon, D.; et al. FimH antagonists: Bioisosteres to improve the in vitro and in vivo PK/PD profile. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 2221–2239.

- Hartmann, M.; Papavlassopoulos, H.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Grabosch, C.; Beiroth, F.; Lindhorst, T.K.; Röhl, C. Inhibition of bacterial adhesion to live human cells: Activity and cytotoxicity of synthetic mannosides. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 1459–1465.

- Stahlhut, S.G.; Struve, C.; Krogfelt, K.A. Klebsiella pneumoniae type 3 fimbriae agglutinate yeast in a mannose-resistant manner. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 61, 317–322.

- Sokurenko, E.V.; Chesnokova, V.; Dykhuizen, D.E.; Ofek, I.; Wu, X.R.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Struve, C.; Schembri, M.A.; Hasty, D.L. Pathogenic adaptation of Escherichia coli by natural variation of the FimH adhesin. Proc. Nat.l Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 8922–8926.

- Sarshar, M.; Scribano, D.; Marazzato, M.; Ambrosi, C.; Aprea, M.R.; Aleandri, M.; Pronio, A.; Longhi, C.; Nicoletti, M.; Zagaglia, C.; et al. Genetic diversity, phylogroup distribution and virulence gene profile of pks positive Escherichia coli colonizing human intestinal polyps. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 112, 274–278.

- Ambrosi, C.; Sarshar, M.; Aprea, M.R.; Pompilio, A.; Di Bonaventura, G.; Strati, F.; Pronio, A.; Nicoletti, M.; Zagaglia, C.; Palamara, A.T.; et al. Colonic adenoma-associated Escherichia coli express specific phenotypes. Microbes Infect. 2019, 21, 305–312.

- Mydock-McGrane, L.K.; Hannan, T.J.; Janetka, J.W. Rational design strategies for FimH antagonists: New drugs on the horizon for urinary tract infection and Crohn’s disease. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2017, 12, 711–731.

- Rafsanjany, N.; Senker, J.; Brandt, S.; Dobrindt, U.; Hensel, A. In vivo consumption of cranberry exerts ex vivo antiadhesive activity against FimH-Dominated uropathogenic Escherichia coli: A combined in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro study of an extract from vaccinium macrocarpon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8804–8818.

- Mayer, K.; Eris, D.; Schwardt, O.; Sager, C.P.; Rabbani, S.; Kleeb, S.; Ernst, B. Urinary tract infection: Which conformation of the bacterial lectin FimH is therapeutically relevant? J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 5646–5662.

- Rosen, D.A.; Pinkner, J.S.; Walker, J.N.; Elam, J.S.; Jones, J.M.; Hultgren, S.J. Molecular variations in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli FimH affect function and pathogenesis in the urinary tract. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 3346–3356.

- Zhou, G.; Mo, W.J.; Sebbel, P.; Min, G.; Neubert, T.A.; Glockshuber, R.; Wu, X.R.; Sun, T.T.; Kong, X.P. Uroplakin Ia is the urothelial receptor for uropathogenic Escherichia coli: Evidence from in vitro FimH binding. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 4095–4103.

- Kątnik-Prastowska, I.; Lis, J.; Matejuk, A. glycosylation of uroplakins. Implications for bladder physiopathology. Glycoconj. J. 2014, 31, 623–636.

- Lewis, A.J.; Richards, A.C.; Mulvey, M.A. Invasion of host cells and tissues by uropathogenic bacteria. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4.

- Bates, J.M.; Raffi, H.M.; Prasadan, K.; Mascarenhas, R.; Laszik, Z.; Maeda, N.; Hultgren, S.J.; Kumar, S. Tamm-Horsfall protein knockout mice are more prone to urinary tract infection: Rapid communication. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 791–797.

- Eto, D.S.; Jones, T.A.; Sundsbak, J.L.; Mulvey, M.A. Integrin-Mediated host cell invasion by type 1-piliated uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3.

- Zalewska-Piątek, B.M.; Piątek, R.J. Alternative treatment approaches of urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2019, 66, 129–138.

- Ribić, R.; Meštrović, T.; Neuberg, M.; Kozina, G. Effective anti-adhesives of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Acta Pharm. 2018, 68, 1–18.

- Hung, C.S.; Bouckaert, J.; Hung, D.; Pinkner, J.; Widberg, C.; DeFusco, A.; Auguste, C.G.; Strouse, R.; Langermann, S.; Waksman, G.; et al. Structural basis of tropism of Escherichia coli to the bladder during urinary tract infection. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 44, 903–915.

- Mydock-McGrane, L.K.; Cusumano, Z.T.; Janetka, J.W. Mannose-Derived FimH antagonists: A promising anti-virulence therapeutic strategy for urinary tract infections and Crohn’s disease. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016, 26, 175–197.

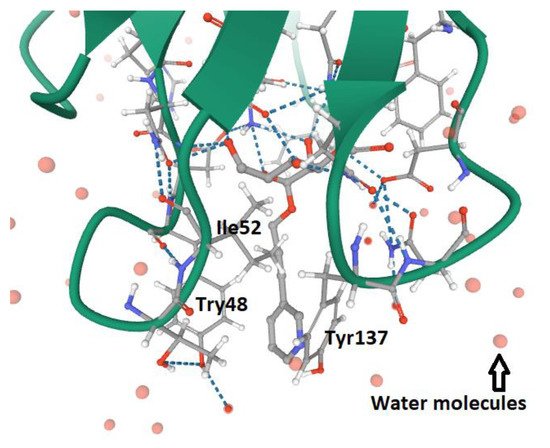

- Wellens, A.; Lahmann, M.; Touaibia, M.; Vaucher, J.; Oscarson, S.; Roy, R.; Remaut, H.; Bouckaert, J. The tyrosine gate as a potential entropic lever in the receptor-binding site of the bacterial adhesin FimH. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 4790–4799.

- Rabbani, S.; Krammer, E.M.; Roos, G.; Zalewski, A.; Preston, R.; Eid, S.; Zihlmann, P.; Prévost, M.; Lensink, M.F.; Thompson, A.; et al. Mutation of Tyr137 of the universal Escherichia coli fimbrial adhesin FimH relaxes the tyrosine gate prior to mannose binding. IUCr J. 2017, 4, 7–23.

- Chen, S.L.; Hung, C.S.; Pinkner, J.S.; Walker, J.N.; Cusumano, C.K.; Li, Z.; Bouckaert, J.; Gordon, J.I.; Hultgren, S.J. Positive selection identifies an in vivo role for FimH during urinary tract infection in addition to mannose binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 22439–22444.

- Duguid, J.P.; Gillies, R.R. Fimbriæ and adhesive properties in dysentery bacilli. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1957, 74.

- Ofek, I.; Mirelman, D.; Sharon, N. Adherence of Escherichia coli to human mucosal cells mediated by mannose receptors. Nature 1977, 265, 623–625.

- Firon, N.; Ofek, I.; Sharon, N. Interaction of mannose-containing oligosaccharides with the fimbrial lectin of Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982, 105, 1426–1432.

- Firon, N.; Ofek, I.; Sharon, N. Carbohydrate specificity of the surface lectins of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Salmonella typhimurium. Carbohydr. Res. 1983, 120, 235–249.

- Neeser, J.R.; Koellreutter, B.; Wuersch, P. Oligomannoside-type glycopeptides inhibiting adhesion of Escherichia coli strains mediated by type 1 pili: Preparation of potent inhibitors from plant glycoproteins. Infect. Immun. 1986, 52, 428–436.

- Koliwer-Brandl, H.; Siegert, N.; Umus, K.; Kelm, A.; Tolkach, A.; Kulozik, U.; Kuballa, J.; Cartellieri, S.; Kelm, S. Lectin inhibition assays for the analysis of bioactive milk sialoglycoconjugates. Int. Dairy J. 2011, 21, 413–420.

- Chalopin, T.; Brissonnet, Y.; Sivignon, A.; Deniaud, D.; Cremet, L.; Barnich, N.; Bouckaert, J.; Gouin, S.G. Inhibition profiles of mono- and polyvalent FimH antagonists against 10 different Escherichia coli strains. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 11369–11375.

- Mydock-McGrane, L.; Cusumano, Z.; Han, Z.; Binkley, J.; Kostakioti, M.; Hannan, T.; Pinkner, J.S.; Klein, R.; Kalas, V.; Crowley, J.; et al. Antivirulence c-mannosides as antibiotic-sparing, oral therapeutics for urinary tract infections. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9390–9408.

- Sattin, S.; Bernardi, A. Glycoconjugates and glycomimetics as microbial anti-adhesives. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 483–495.

- Ernst, B.; Magnani, J.L. From carbohydrate leads to glycomimetic drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 661–677.

- Firon, N.; Ashkenazi, S.; Mirelman, D.; Ofek, I.; Sharon, N. Aromatic alpha-glycosides of mannose are powerful inhibitors of the adherence of type 1 fimbriated Escherichia coli to yeast and intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 1987, 55, 472–476.

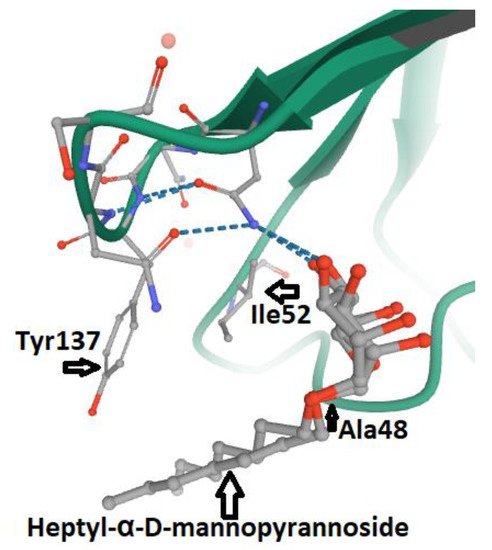

- Vanwetswinkel, S.; Volkov, A.N.; Sterckx, Y.G.; Garcia-Pino, A.; Buts, L.; Vranken, W.F.; Bouckaert, J.; Roy, R.; Wyns, L.; van Nuland, N.A. Study of the structural and dynamic effects in the FimH adhesin upon α-d-heptyl mannose binding. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1416–1427.

- Chabre, Y.M.; Roy, R. Multivalent glycoconjugate syntheses and applications using aromatic scaffolds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4657–4708.

- Lee, Y.C.; Lee, R.T. Carbohydrate-protein interactions: Basis of glycobiology. Acc. Chem. Res. 1995, 28, 321–327.

- Hartmann, M.; Lindhorst, T.K. The bacterial lectin FimH, a target for drug discovery-carbohydrate inhibitors of type 1 fimbriae-mediated bacterial adhesion. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 3583–3609.

- Bouckaert, J.; Mackenzie, J.; de Paz, J.L.; Chipwaza, B.; Choudhury, D.; Zavialov, A.; Mannerstedt, K.; Anderson, J.; Piérard, D.; Wyns, L.; et al. The affinity of the FimH fimbrial adhesin is receptor-driven and quasi-independent of Escherichia coli pathotypes. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 61, 1556–1568.

- Han, Z.; Pinkner, J.S.; Ford, B.; Obermann, R.; Nolan, W.; Wildman, S.A.; Hobbs, D.; Ellenberger, T.; Cusumano, C.K.; Hultgren, S.J.; et al. Structure-Based drug design and optimization of mannoside bacterial FimH antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4779–4792.

- Schönemann, W.; Lindegger, M.; Rabbani, S.; Zihlmann, P.; Schwardt, O.; Ernst, B. 2-C-Branched mannosides as a novel family of FimH antagonists-synthesis and biological evaluation. Perspect. Sci. 2017, 11, 53–61.

- Ribić, R.; Meštrović, T.; Neuberg, M.; Kozina, G. Proposed dual antagonist approach for the prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Med. Hypotheses 2019, 124, 17–20.

- Sehad, C.; Shiao, T.C.; Sallam, L.M.; Azzouz, A.; Roy, R. Effect of dendrimer generation and aglyconic linkers on the binding properties of mannosylated dendrimers prepared by a combined convergent and onion peel approach. Molecules 2018, 23, 1890.

- Touaibia, M.; Krammer, E.M.; Shiao, T.C.; Yamakawa, N.; Wang, Q.; Glinschert, A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Mousavifar, L.; Maes, E.; Oscarson, S.; et al. Sites for dynamic protein-carbohydrate interactions of O- and C-Linked mannosides on the E. coli FimH adhesin. Molecules 2017, 22, 1101.

- Kalas, V.; Hibbing, M.E.; Maddirala, A.R.; Chugani, R.; Pinkner, J.S.; Mydock-McGrane, L.K.; Conover, M.S.; Janetka, J.W.; Hultgren, S.J. Structure-Based discovery of glycomimetic FmlH ligands as inhibitors of bacterial adhesion during urinary tract infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2819–E2828.

- Johnson, B.K.; Abramovitch, R.B. Small molecules that sabotage bacterial virulence. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 339–362.

- Asadi, A.; Razavi, S.; Talebi, M.; Gholami, M. A review on anti-adhesion therapies of bacterial diseases. Infection 2019, 47, 13–23.

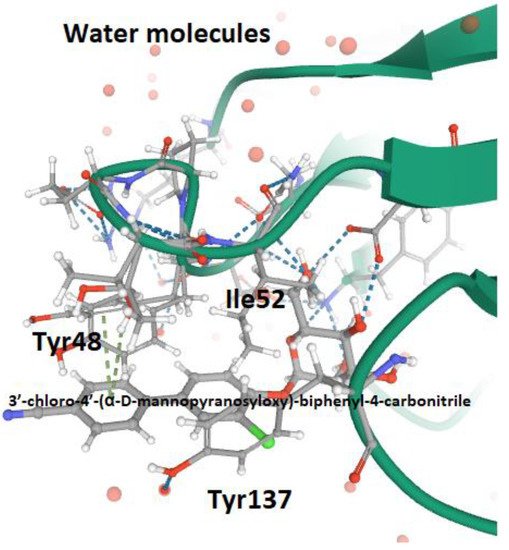

- Bouckaert, J.; Berglund, J.; Schembri, M.; De Genst, E.; Cools, L.; Wuhrer, M.; Hung, C.S.; Pinkner, J.; Slättegård, R.; Zavialov, A.; et al. Receptor binding studies disclose a novel class of high-affinity inhibitors of the Escherichia coli FimH adhesin. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 441–455.

- Mousavifar, L.; Vergoten, G.; Charron, G.; Roy, R. Comparative study of aryl O-, C-, and S-mannopyranosides as potential adhesion inhibitors toward uropathogenic E. coli FimH. Molecules 2019, 24, 3566.

- Mousavifar, L.; Touaibia, M.; Roy, R. Development of mannopyranoside therapeutics against adherent-invasive Escherichia coli infections. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2937–2948.

- Klein, T.; Abgottspon, D.; Wittwer, M.; Rabbani, S.; Herold, J.; Jiang, X.; Kleeb, S.; Lüthi, C.; Scharenberg, M.; Bezençon, J.; et al. FimH antagonists for the oral treatment of urinary tract infections: From design and synthesis to in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 8627–8641.

- Han, Z.; Pinkner, J.S.; Ford, B.; Chorell, E.; Crowley, J.M.; Cusumano, C.K.; Campbell, S.; Henderson, J.P.; Hultgren, S.J.; Janetka, J.W. Lead optimization studies on FimH antagonists: Discovery of potent and orally bioavailable ortho-substituted biphenyl mannosides. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3945–3959.

- Schwardt, O.; Rabbani, S.; Hartmann, M.; Abgottspon, D.; Wittwer, M.; Kleeb, S.; Zalewski, A.; Smieško, M.; Cutting, B.; Ernst, B. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of mannosyl triazoles as FimH antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 6454–6473.

- Heidecke, C.D.; Lindhorst, T.K. Iterative synthesis of spacered glycodendrons as oligomannoside mimetics and evaluation of their antiadhesive properties. Chemistry 2007, 13, 9056–9067.

- Gupta, K.; Chou, M.Y.; Howell, A.; Wobbe, C.; Grady, R.; Stapleton, A.E. Cranberry products inhibit adherence of p-fimbriated Escherichia coli to primary cultured bladder and vaginal epithelial cells. J. Urol. 2007, 177, 2357–2360.

- Hisano, M.; Bruschini, H.; Nicodemo, A.C.; Srougi, M. Cranberries and lower urinary tract infection prevention. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012, 67, 661–668.

- Nicolosi, D.; Tempera, G.; Genovese, C.; Furneri, P.M. Anti-Adhesion activity of A2-type proanthocyanidins (a Cranberry Major Component) on uropathogenic E. coli and P. mirabilis Strains. Antibiotics 2014, 3, 143–154.

- Scharf, B.; Sendker, J.; Dobrindt, U.; Hensel, A. Influence of cranberry extract on tamm-horsfall protein in human urine and its antiadhesive activity against uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 126–138.