Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Harlina Suzana Jaafar | + 3026 word(s) | 3026 | 2021-12-07 03:42:25 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | Meta information modification | 3026 | 2021-12-10 03:31:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Jaafar, H. Creating Innovation in Achieving Sustainability: Halal-Friendly Sustainable Port. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16963 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Jaafar H. Creating Innovation in Achieving Sustainability: Halal-Friendly Sustainable Port. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16963. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Jaafar, Harlina. "Creating Innovation in Achieving Sustainability: Halal-Friendly Sustainable Port" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16963 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Jaafar, H. (2021, December 10). Creating Innovation in Achieving Sustainability: Halal-Friendly Sustainable Port. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16963

Jaafar, Harlina. "Creating Innovation in Achieving Sustainability: Halal-Friendly Sustainable Port." Encyclopedia. Web. 10 December, 2021.

Copy Citation

The expansion of liberalized trade has forced companies to consider the global market demand to stay competitive. Hence, ports have started to embrace sustainability practices in their activities throughout port operations. Various research has suggested that there is more innovation when sustainability is adopted as an integral part of their business activities.

sustainability

innovation

ports

halal

environmental

supply chain

1. Introduction

The rise in green and sustainability brings a wave of change to the port and logistics industry [1][2][3]. Koilo [4] highlighted that practitioners are increasingly interested in sustainability issues in the maritime logistics and supply chain industry. This means that the international ports need to fulfill the requirements to be a sustainable port while being able to oblige to customer demand to stay competitive. In terms of economy, the increasing development of liberalization of trade and services has also called for companies to continuously be responsive to the global market demand to remain relevant. Hence, ports have started to embrace sustainability practices in their activities throughout port operations by placing priorities toward achieving economic, eco-social, and efficient operational goals [5][6][7][8]. Various research convinced that innovation is stimulated when sustainability is adopted as a fundamental part of their commercial activities [9][10][11][12].

In another stream of studies, several researchers emphasized that innovation could increase profits, help to cut costs [13][14][15][16], or enhance the quality of current process [17] and increase competitiveness [18]. Flint et al. [19] pointed out that innovation is significant to the logistics industry as it drives companies to be more competitive. However, the concept of innovation has been mainly disregarded in logistics research. They noted that many studies exploring innovation have put much emphasis on product innovation, especially innovation on high technology.

In another scenario, the concept of halal has increasingly attracted business widely. It is a concept gained from the Islamic principles that Muslims must consume halal products. Halal is obtained when all process, including the production and delivery of the products to the final consumers, comply with the Islamic principles. The requirements to be halal are to ensure that the products are free from contamination with haram (forbidden by Islamic law) and hazardous products. As a result, the non-Muslims are becoming attracted to the safety and quality aspect of the halal products. The religious requirement has created the demand for halal products. The failure to consume halal products would result in a sin committed by the Muslims. From the business perspective, halal practice has been considered as a business strategy that would bring market expansion [20] as it addresses the growing number of Muslims and non-Muslims worldwide. The existing literature indicates the focus on producing the halal products from the manufacturing perspective. However, it is insufficient to reach the status of halal products when it reaches the final consumers [21][22][23][24]. Throughout these supply chain activities, several conditions could expose the halal products to the risk of contamination with haram and hazardous substances that would affect the halal status of the product when it reaches the final consumers. Those activities involve handling, storage, warehousing, and transportation, as well as sourcing and manufacturing.

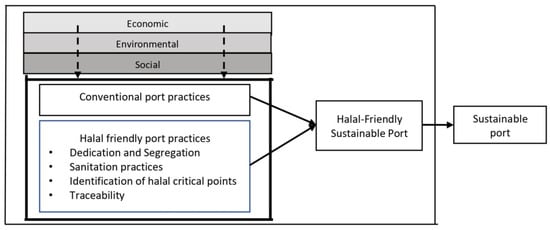

2. Development of Halal-Friendly Sustainable Port (HFSP) Model

Based on the initial interviews and focus group discussion, the respondents generally supported the halal-friendly port as a potential innovation in achieving sustainable practices. Being a Muslim majority country, most respondents are concerned of their responsibility to consume halal goods. Any halal issues should be addressed to ensure that Muslim consume true halal goods. They are also aware of the increasing demand of halal goods throughout the world and having a supply chain of halal goods is particularly crucial to fulfill the consumers’ needs to obtain completely halal goods that comply to the Syariah principle throughout the entire supply chain process. However, they are not aware of the role that they may play in part of the halal supply chain implementation. In most countries, the halal implementation and certification are widely available for the manufacturing of food and beverages only. They do not realize that product contamination may also occur during the handling, transportation, and storing activities along the supply chain. In the context of international trade of halal products, the port handles several activities that may expose the halal products to contamination. Since the purpose of the halal practice is to avoid contamination of haram and hazardous elements, ports play a crucial role as an international gateway in the halal supply chain; thus, they need to comply to the halal requirements. Accordingly, they are eager to learn the roles they can play to fulfil these needs. Most participants in the focus group agreed that the implementation of halal logistics in the port area may address the contamination of halal cargoes handled in ports. The consensus on the feasibility of HFSP implementation among the focus group members led to the discussion on the identification of the criteria needed to establish HFSP. The reviews on the literature and interviews with the port authority prior to the focus group indicates four variables that contribute to the successful implementation of HFSP. The findings from the focus group supported that (1) dedication and segregation practices, (2) sanitation practices in the port operations, (3) determination of halal control points, and (4) traceability of the halal cargo (refer to Figure 1) are four that are vital components for HFSP establishment.

Figure 1. Halal-Friendly Sustainable Port Model.

The components were developed based on halal practices that were derived from the Islamic guidelines that determine the sources of contamination. These can come from haram and harmful sources; thus, halal products can become haram (forbidden) and hazardous, and unsafe for consumption [25]. The lack of temperature control and the sanitation practices may also lead to the contamination of the cargo [26]. This scenario has led to the consensus among the participants of the following components determined as critical in the development of the HFSP model.

2.1. Dedication and Segregation Practices

The findings demonstrate that the practice of HFSP should be based on two types of principle practices: segregation and dedication. When the logistics operations are solely dedicated for halal cargoes, there are less possibilities for the cargoes to be contaminated, thus reducing the number of halal control points. Halal control point is a point, step, or procedure, whereby control can be imposed, and contamination can be prevented and eliminated [27][28][29][30][31][32]. However, when the halal and non-halal cargoes or hazardous and non-hazardous cargoes are consolidated, the principle of segregation should be applied. This is because the possibilities of the cargoes to be contaminated are higher when these cargoes are consolidated. However, in handling the cold chain products, temperature should be controlled to avoid contamination in both situations. To implement a dedicated service, ports may allocate designated areas for halal declared cargoes. This dedicated service is feasible with full container load (FCL) types of shipment in comparison to less container load (LCL) because the container is loaded by halal certified shippers. However, in cases where it is almost impossible to dedicate halal cargo services, the principle of segregation should be applied.

These scenarios have become a major concern among the port stakeholders, especially regarding cost, which has led to several misconceptions on the feasibility of its implementation. They perceive that HFSP requires total transformation of the entire port process flow and may involve heavy investments when the rate of return of the investments is still uncertain. Although the paper is developed based on an ongoing study, the initial findings showed that the implementation of HFSP may involve minor adjustments of the port system, such as the declaration of halal goods in the documentation process, as well as physical cargo flow. HFSP is developed as a value-added service offered to the customer; therefore, the transformation of the entire port system is unnecessary. The additional line of halal cargo handling would not affect other port operations. The halal cargo handling may adopt similar practices to the handling of fragile and temperature-sensitive cargoes.

2.2. Sanitation Practices in Halal Logistics Operation

The standards of halal supply chain underline that cleanliness forms one of its vital components [27][28][29]. Thus, sanitation practices should be listed among the halal supply chain activities. Sanitation has been described by the World Health Organization as the provision of facilities and services for the safe removal of human urine and feces. It explains how hygienic conditions should be preserved through services, such as garbage collection and wastewater disposal. Marriot et al. [33] defined sanitation as “the creation and maintenance of hygienic and healthful conditions.” Sanitation in halal logistics requirements covers the general requirements for premises, infrastructure, facilities, and workers.

The purposes of sanitation are as follows:

-

To reduce contamination and promote the well-being of equipment, workers, and customers;

-

To provide a healthy and pleasant environment;

-

To protect the natural resources (e.g., surface water, groundwater, and soil) as well as to provide safety, security, and dignity for people when they defecate or urinate;

-

To provide barriers between excreta and humans so that the chain of disease and infections could be stopped;

-

To have and promote sustainable sanitation, particularly in developing countries;

-

To meet regulatory environment.

In the context of this study, the suggestion on sanitation practices in port areas were well received by the participants, particularly at the warehouse areas.

2.3. Halal Control Point (HCP)

Following the above, to successfully implement the HFSP operations, the port operator needs to identify the halal control points that may cause contamination to occur on the halal cargoes. Throughout the process flow in the port area, this study found four halal control points, namely:

-

Declaration of halal cargoes at the port entry point;

-

Loading and unloading of cargoes;

-

Storage and warehousing;

-

Cargo inspection.

These halal control points (HCPs) are crucial as it associates with a certain degree of contamination risk towards the halal cargoes. The contamination refers to the contamination with haram and contamination with hazardous, or the halal cargo itself could be contaminated and become haram and hazardous due to lack of monitoring and control during the handling process. HCPs were identified based on guidelines underlined by the Islamic principles. The determination of HCPs along the process flow is vital to ensure that the risks associated with halal cargoes could be eliminated. To preserve the HCP, control measures need to be determined so that prevention may be conducted to reduce the risk of contamination. In any case of contamination occurrence, corrective actions that have been recognized earlier should be taken.

The consensus of non-conformity should be derived from the port operation staff and the Syariah (Islamic law) experts to ensure that halal practices are in line with the halal guidelines. The failure to comply with the standard operating procedure may lead to non-conformity of the process activities, such as the failure to declare the halal cargoes and thus subject to the conduct of corrective actions whenever possible.

2.4. Traceability

The establishment of an effective traceability system was found as crucial to ensure the quality and safety of the halal cargoes, and that product recall may be performed in any event of contamination. This traceability system would then act as an effective tool when the supply chain transparency is improved [34][35][36]. Several authors highlighted the lack of food traceability when the food products and production process information were often mishandled and missing in the companies, as well as among companies along the supply chain [37][38][39][40]. They urged for more detailed studies to be conducted at every stage of the supply chain process so that these processes could be documented, and the issues could be addressed [41][42][43][44]. None of the focus group members were against the fact that traceability drives an efficient halal supply chain within port operations.

Monitoring the movement of halal cargoes and its quality, as well as the process constraints throughout its flow in the port area, complements the safety and quality of the halal cargoes in the entire supply chain. A system that can serve both internal and external supply chain traceabilities is crucial in the development of a fully traceable supply chain [36].

However, despite being regarded as a feasible operation, the requirements to be HFSP were viewed as a complex transformation process by some of the port stakeholders. Thus, they were not convinced with the newly introduced concept of HFSP due to the lack of evidence of a current successful halal port practice. Thus, the implementation of HFSP received low priority among port operators as they have chosen to focus on other strategic priorities of investment, such as digitalization and green practice towards meeting sustainable development goals (SDGs). However, most port stakeholders considered it as a new business model strategy to attract more port stakeholders to choose HFSP as a port of call due to new service offerings that address the SDGs.

3. Mapping the Implementation of HFSP to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

This study embedded all three components of the triple bottom line (i.e., environmental, economic, and social) to produce a sustainability value to the port. Table 1 maps the targets and indicators of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) that could be met by halal-friendly sustainable port.

Table 1. The halal-friendly sustainable port model’s attainment of Sustainable Development Goals.

| Components | Goals | Targets | HFSP: Meeting the Targets of SDG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | 3. Good Health and Well Being Ensures healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages |

3.9 By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. | The foundation of halal practice (i.e., to avoid contamination) may ensure that final goods that reach consumers are safe to be consumed and that the quality may promote health and well-being of the society. |

| Economic | 9. Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation. |

9.1 Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all. | As one of the crucial transport infrastructures, ports could promote industry innovation through the development of value-added services of halal handling that could offer choices to the halal certified manufacturers. |

| Social | 10. Reduced Inequalities Reduce inequality within and among countries |

10.2 By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status. | Addressing the needs of the Muslims dietary requirements that demand them to consume halal food may encourage inclusion of all irrespective of religion. |

| Environment | 12. Responsible Consumption and Production Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

12.3 By 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses. 12.8 By 2030, ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature. |

The reduction in contamination may reduce waste, thus indicating the ability of the model to complement that part of supply chain to reduce food waste and food losses along production and supply chains. Halal-friendly sustainable port forms part of the halal supply chain may create awareness among the society on the importance to have a sustainable lifestyle that move in tandem with nature when the supply chain of halal is completed from end to end. |

| Social | 17. Partnerships for the Goals: A successful sustainable development agenda requires partnerships between governments, the private sector and civil society. These inclusive partnerships built upon principles and values, a shared vision, and shared goals that place people and the planet at the centre, are needed at the global, regional, national and local level. |

17.11 Significantly increase the exports of developing countries, with a view to doubling the least developed countries’ share of global exports by 2020. | Implementing Halal-friendly sustainable port requires cooperation and collaboration among various stakeholders in the port community. Thus, it supports the country aspirations to be the Global Halal Hub through sufficient capacity handling for halal domestic and export cargo. |

From an economic perspective, the aim of avoiding contamination from haram and hazardous cargo in the port area may assist in achieving target 3.9 under Goal 3, i.e., to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages. Ports, as one of the crucial transport infrastructures at the border, also play a key role in economic perspectives to achieve target 9.1 from Goal 9. The new value-added services offered to the customers in addition to the current port services may enhance the development of quality, reliability, sustainability, and resilience of the port to support the economic development. As more halal certified companies emerge in the market, the demand of halal cargo handling will also materialize. HFSP will provide new service offerings that provide choices to their customer, who would like to have a specific service of halal cargo handling, transportation, and storage, leading to service fulfilment.

The reduction in contamination rates may reduce waste, indicating the ability of the model to complement that part of the supply chain to meet the environment target 12.3, particularly by reducing food waste and food losses along the production and supply chains. By introducing HFSP as part of the halal supply chain, the society is going to be more aware of the importance of having a sustainable lifestyle that moves in tandem with nature when the supply chain of halal is completed from end to end and can lead to the achievement of target 12.8.

Accordingly, the social element in this model is reflected in the responsibility of the port in ensuring that the halal cargo handling is free from contamination with haram and hazardous substances, hence influencing the customers’ trust in the port operator. The halal certification holds the branding that guarantees the quality of port services as it reflects its compliance to the halal supply chain standard guideline. Accordingly, it aims to meet target 10.2, i.e., empower and promote the social, economic, and political inclusion of all, irrespective of religion or other status. Thus, the model addresses the crucial requirement of the increased number of Muslims worldwide in accommodating their dietary needs that may also benefits others due to the halal product quality. Implementing a HFSP requires cooperation and collaboration among various stakeholders in the port community. Thus, it supports the country’s aspirations to be the Global Halal Hub through sufficient capacity handling for domestic and export cargo, leading to the attainment of target 17.11.

The assimilation of all these sustainability elements qualifies the model to be called a HFSP.

References

- Acciaro, M.; Ghiara, H.; Cusano, M.I. Energy Management in Seaport: A New Role for Port Authorities. Energy Policy 2014, 71, 4–12.

- Lam, J.S.L.; Notteboom, T. The Greening of Ports: A Comparison of Port Management Tools Used by Leading Ports in Asia and Europe. Transp. Rev. 2014, 34, 169–189.

- Parola, F.; Risitano, M.; Ferretti, M.; Panetti, E. The Drivers of Port Competitiveness: A Critical Review. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 116–138.

- Koilo, V. Sustainability Issues in Maritime Transport and Main Challenges of the Shipping Industry. Environ. Econ. 2019, 10, 48–65.

- Cheon, S.H.; Deakin, E. Supply Chain Coordination for Port Sustainability. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2166, 10–19.

- Denktas-Sakar, G.; Karatas-Cetin, C. Port Sustainability and Stakeholder Management in Supply Chains: A Framework on Resource Dependence Theory. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2012, 28, 301–320.

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a Literature Review to a Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710.

- Wagner, M. The Role of Corporate Sustainability Performance for Economic Performance: A Firm-Level Analysis of Moderation Effects. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1553–1560.

- Adams, C.A. The Sustainable Development Goals, Integrated Thinking and the Integrated Report; International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and ICAS: London, UK, 2017.

- Calic, G.; Mosakowski, E. Kicking Off Social Entrepreneurship: How a Sustainability Orientation Influences Crowdfunding Success. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 738–767.

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F. Beyond the Bounded Instrumentality in Current Corporate Sustainability Research: Toward an Inclusive Notion of Profitability. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 325–345.

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business Models for Sustainability: A Coevolutionary Analysis of Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Transformation. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 264–289.

- Calantone, R.; Tamer Cavusgil, S.; Zhao, Y. Learning Orientation, Firm Innovation Capability and Firm Performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2002, 31, 515–524.

- Dilk, C.; Gleich, R.; Wald, A.; Motwani, J. State and Development Innovation Networks: Evidence from the European Vehicle Sector. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 691–701.

- Grawe, S.J.; Chen, H.; Daugherty, P.J. The Relationship Between Strategic Orientation, Service Innovation, and Performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 282–300.

- Kandampully, J. Innovation as the Core Competency of a Service Organisation: The Role of Technology, Knowledge and Networks. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2002, 5, 18–26.

- Khazanchi, S.; Lewis, M.W.; Boyer, K.K. Innovation-Supportive Culture: The Impact of Organizational Values on Process Innovation. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 871–884.

- McGrath, R.G.; Ming Hone, T.; Venkataraman, S.; MacMillan, I.C. Innovation, Competitive Advantage and Rent: A Model and Test. Manag. Sci. 1996, 42, 389–403.

- Flint, D.J.; Larson, E.; Gammelgaard, B.; Mentzer, J.T. Logistics Innovation: A Customer Value-Oriented Social Process. J. Bus. Logist. 2005, 26, 113–147.

- Nik Muhammad, N.M.; Md Isa, F.; Kifli, B.C. Positioning Malaysia as Halal Hub: Integration Role of Supply Chain Strategy and Halal Assurance System. Asian Soc. Sci. J. 2009, 5, 44–52.

- Mohd Bahruddin, S.S.; Ilyas, M.I.; Desa, M.I. Tracking and Tracing Technology for Halal Product Integrity over the Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Bandung, Indonesia, 17–19 July 2011.

- Jaafar, H.S.; Endut, I.R.; Faisol, N.; Omar, E.N. Innovation in Logistics Services: Halal Logistics. In Proceedings of the 16th International Symposium on Logistics (ISL), Berlin, Germany, 10–13 July 2011; pp. 844–851.

- Omar, E.N.; Jaafar, H.S. Halal Supply Chain in the Food Industry—A Conceptual Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Business, Engineering and Industrial Applications (ISBEIA), Langkawi, Kedah, Malaysia, 25–28 September 2011.

- Omar, E.N.; Jaafar, H.S.; Osman, M.R.; Faisol, N. Halalan Tayyiban Supply Chain: The New Insights in Sustainable Supply Chain Management. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Logistics and Transport (ICLT 2013), Kyoto, Japan, 5 November 2013; p. 137.

- Al-Qaradawi, Y. The Lawful and Prohibited in Islam; Al Falah Foundation for Translation, Publication and Distribution: Cairo, Eqypt, 2001.

- International Forwarding Association. Risks for Food Manufacturers during Shipping. Available online: https://ifa-forwarding.net/blog/sea-freight-in-europe/risks-for-food-manufacturers-during-shipping/ (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Department of Standards Malaysia. Halal Supply Chain Management System—Part 1: Transportation—General Requirements (First Revision); Department of Standards: Selangor, Malaysia, 2019.

- Department of Standards Malaysia. Halal Supply Chain Management System—Part 2: Warehousing—General Requirements (First Revision); Department of Standards: Selangor, Malaysia, 2019.

- Department of Standards Malaysia. Halal Supply Chain Management System—Part 3: Retailing—General Requirements (First Revision); Department of Standards: Selangor, Malaysia, 2019.

- The Standards and Metrology Institute for Islamic Countries. OIC/SMIIC 17-1:2020 Halal Supply Chain Management System—Part 1: Transportation—General Requirements, 1st ed.; SMIIC: Istanbul, Turkey, 2020.

- The Standards and Metrology Institute for Islamic Countries. OIC/SMIIC 17-1:2020 Halal Supply Chain Management System—Part 2: Warehousing—General Requirements, 1st ed.; SMIIC: Istanbul, Turkey, 2020.

- The Standards and Metrology Institute for Islamic Countries. OIC/SMIIC 17-1:2020 Halal Supply Chain Management System—Part 3: Retailing—General Requirements, 1st ed.; SMIIC: Istanbul, Turkey, 2020.

- Marriott, N.G.; Schilling, M.W.; Gravani, R.B. Principles of Food Sanitation, 6th ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018.

- Comba, L.; Belforte, G.; Dabbene, F.; Gay, P. Methods for Traceability in Food Production Processes Involving Bulk Products. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 116, 51–63.

- Dabbene, F.; Gay, P.; Tortia, C. Traceability Issues in Food Supply Chain Management: A Review. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 120, 65–80.

- Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Moga, L.M.; Neculita, M. Modelling and Implementation of the Vegetable Supply Chain Traceability System. Food Control 2013, 30, 341–353.

- Bertolini, M.; Bevilacqua, M.; Massini, R. FMECA Approach to Product Traceability in the Food Industry. Food Control 2006, 17, 137–145.

- Donnelly, K.A.M.; Karlsen, K.M.; Dreyer, B. A Simulated Recall study in Five Major Food Sectors. Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 1016–1031.

- Donnelly, K.A.M.; Karlsen, K.M.; Olsen, P. The Importance of Transformations for Traceability—A Case Study of Lamb and Lamb Products. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 68–73.

- Frederiksen, M.T.; Bremner, A. Fresh Fish Distribution Chains: An Analysis of Three Danish and Three Australian Chains. Food Aust. 2001, 54, 117–123.

- Bechini, A.; Cimino, M.G.C.A.; Marcelloni, F.; Tomasi, A. Patterns and Technologies for Enabling Supply Chain Traceability through Collaborative e-Business. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2008, 50, 342–359.

- Främling, K.; Ala-Risku, T.; Kärkkäinen, M.; Holmström, J. Agent-Based Model for Managing Composite Product Information. Comput. Ind. 2006, 57, 72–81.

- Karlsen, K.M.; Olsen, P. Validity of Method for Analysing Critical Traceability Points. Food Control 2011, 22, 1209–1215.

- Li, M.; Qian, J.P.; Yang, X.T.; Sun, C.H.; Ji, Z.T. A PDA-Based Record-Keeping and Decision-Support System for Traceability in Cucumber Production. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2010, 70, 69–77.

More

Information

Subjects:

Business

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

940

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

10 Dec 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No