Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Zhao, H. NiO-TiO2 p-n Heterojunction. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16608 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Zhao H. NiO-TiO2 p-n Heterojunction. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16608. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Zhao, Heng. "NiO-TiO2 p-n Heterojunction" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16608 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Zhao, H. (2021, December 01). NiO-TiO2 p-n Heterojunction. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16608

Zhao, Heng. "NiO-TiO2 p-n Heterojunction." Encyclopedia. Web. 01 December, 2021.

Copy Citation

NiO is a typical p-type semiconductor and it has widely been combined with TiO2 to form the p-n heterojunction due to its suitable energy band structure, high charge carrier concentration, high chemical stability and low cost. Decreasing the size of NiO to nanoclusters helps to improve the electron transfer channels on the surface of TiO2, thus enhance photocatalytic hydrogen production efficiency.

hydrogen production

photocatalysis

p-n heterojunction

NiO

TiO2

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, environmental pollution and energy depletion have become increasingly critical. Photocatalysis has been realized as a potential strategy to solve these two global issues [1]. For a long time, environmental photocatalysis over semiconductors has been widely investigated for environmental remediation such as waste water treatment [2]. Since Fujishima and Honda firstly demonstrated the photoelectrolysis of water over crystalline TiO2, photocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen production and photocatalytic carbon dioxide valorization have also attracted great attention as the environmentally friendly solutions to further overcome energy and environmental crisis [3][4][5]. Solar-driven water splitting over transition metal oxides [6][7][8], composite oxides [9][10], carbonitride and chalcogenides [11][12] have been widely investigated, wherein n-type anatase TiO2 is the most commonly used photocatalyst due to its nontoxicity, high chemical stability, cost-effectiveness and facile structure modification [13][14]. However, its limited quantum efficiency because of the high recombination rate of electron-hole pairs and its intrinsic wide band gap still hinder its commercialization. Herein, numerous strategies have been applied to improve the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 materials, such as forming heterostructure with other semiconductors, doping, dye sensitization, and exposed facets modification [14][15]. Among them, heterostructures has been revealed to be an efficient method to improve photocatalytic efficiency [16][17][18][19]. As a typical heterostructure, p-n junction constructed by combining a n-type semiconductor (electron-rich) with a p-type semiconductor (hole-rich) can be a very efficient strategy to realize the separation of photogenerated electrons and holes. The charge separation is spontaneously driven by a formed built-in electric field and then the enhanced photocatalytic performance can be realized [20][21][22].

NiO is a typical p-type semiconductor and it has widely been combined with TiO2 to form the p-n heterojunction due to its suitable energy band structure, high charge carrier concentration, high chemical stability and low cost [23]. To date, many methods have already been developed to prepare NiO-TiO2 nanocomposites, such as hydrothermal, incipient wetness impregnation, sol-gel, and evaporation-induced methods [24][25][26][27]. Although an inner-built electric field is a very efficient manner to improve the transfer of charge carriers between TiO2 and NiO, the commonly fabricated nanocomposites usually suffer an untight contact between these two components, leading to a fast charge accumulation at a nanoparticle surface during the photocatalytic process. These accumulated charges become a recombination center to reduce the photocatalytic quantum efficiency.

2. Discussion

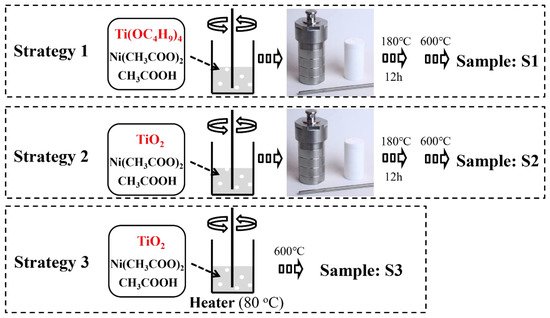

Figure 1 illustrates three fabrication processes for NiO-TiO2 nanoparticles. Strategy 1 (S1) shows a process by using both precursors of NiO and TiO2 (nickel acetate and tetraisopropyl titanate) directly. A nanocrystal of TiO2 covered by NiO clusters can be obtained during a sol-gel process and the following thermal treatment endows the nanocrystal with high crystallinity. This method can generate NiO-TiO2 nanocomposites with low NiO loading according to our previous work [28]. However, this method also leads to a crystal transformation of NiO to form NiTiO3, which has negative effects on photocatalytic hydrogen production [29]. To avoid the formation of NiTiO3, crystalline TiO2 was used to replace its precursor tetraisopropyl titanate in strategy 2 (S2). During a hydrothermal process, nickel ions are only absorbed on a surface of TiO2 rather than penetrated into TiO2 crystal as the high crystallinity of TiO2 inhibits a crystal transformation. NiO-TiO2 nanocomposites with a high dispersion of NiO can herein be obtained after calcination. However, the second strategy can only prepare NiO-TiO2 nanocomposites with a low NiO loading due to a weak electrostatic adsorption ability of a TiO2 surface. Herein, to further improve the loading of NiO, strategy 3 (S3) was employed by directly heating the suspension of TiO2 and nickel acetate followed by calcination. The effects of photocatalyst preparation strategies on NiO loading, a crystal size, a pore size/distribution, and photocatalytic hydrogen production were compared as shown in Table 1. It appears that the samples from S1 have almost the same parameters and performance as those from S2. Higher NiO content endows the samples from S1 and S2 with better photocatalytic hydrogen production. However, further increasing NiO content by S3 causes a decrease in hydrogen evolution.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of three different fabrication processes for NiO-TiO2 nanoparticles.

Table 1. Structural parameters along with photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of each sample.

| Sample | NiO Content (wt%) | Crystallite Size XRD (nm) | Crystallite Size SEM (nm) | SBET/m2g−1 | Pore Size (nm) | H2 Evolution rate/mmolh−1g−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiO | - | 55 | 40–80 | 9.5 | N/A | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| TiO2 | - | 25 | 20–30 | 31.9 | 5–50 | 6.6 ± 0.7 |

| S1-10% | 1.7 | 20 | 20–40 | 38.0 | 5–50 | 17.7 ± 0.9 |

| S1-20% | 3.3 | 30 | 20–40 | 39.5 | 5–50 | 23.5 ± 1.2 |

| S2-10% | 1.5 | 35 | 25–45 | 36.4 | 5–40 | 16.3 ± 0.8 |

| S2-20% | 3.1 | 35 | 25–45 | 35.6 | 5–40 | 20.4 ± 1.0 |

| S3-10% | 9.8 | 40 | 30–50 | 50.7 | 5–40 | 8.9 ± 0.7 |

| S3-20% | 19.4 | 45 | 30–50 | 52.7 | 5–40 | 8.8 ± 0.7 |

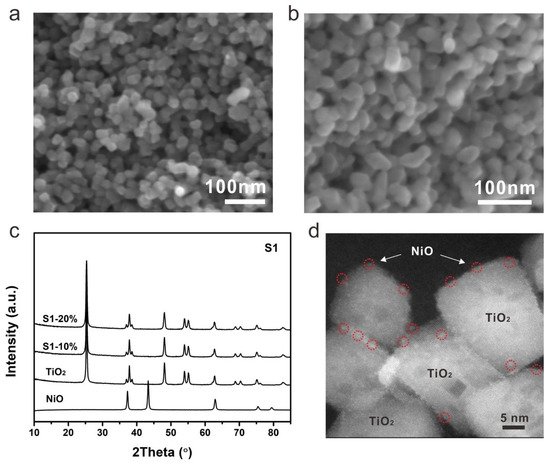

The morphology of NiO-TiO2 composites prepared by strategy 1 was firstly investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Nanocrystals with a size of around 20 nm can be clearly observed for S1-10% (Figure 2a). Further increasing the loading of NiO, the size increased to around 30 nm for S2-20% (Figure 2b). The XRD patterns demonstrated that both S1-10% and S1-20% were mainly composed by anatase TiO2 with high crystallinity, indicating the presence of NiO with extremely low content in the as-fabricated composites (Figure 2c). The presence and distribution of NiO can be revealed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). NiO nanocrystals with a size of around 30 nm were observed, with high crystallinity as evidenced by the distinguishable lattice fringe (Figure 3d). Numerous bright dots can be clearly observed on the surface of a TiO2 nanocrystal, which were ascribed to the loaded NiO, indicating that the presence of NiO was in the form of an ultrafine nanocluster and its distribution was uniform on the surface of TiO2. The even dispersion of NiO increases the photocatalytic performance due to the formation of numerous p-n heterojunction channels. However, the content of NiO by this method was limited to <3.33% as further increasing NiO loading would introduce the formation of NiTiO3 [28].

Figure 2. SEM images of (a) S1-10% and (b) S1-20%, (c) XRD patterns and (d) HR-TEM image of S1-20%.

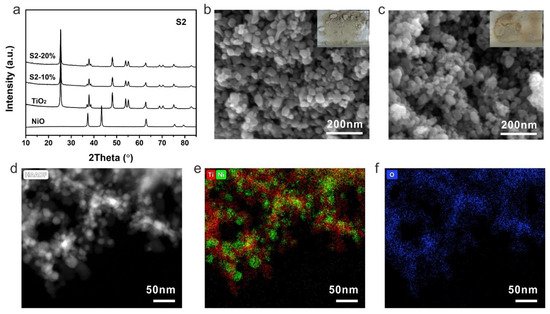

Figure 3. (a) XRD patterns, SEM images of (b) S2-10%, (c) S2-20%, (d) HAADF-STEM image of S2-20% and the corresponding elemental mapping (e) Ti (red), Ni (green) and (f) O (blue). Insets are the corresponding photographs of S2-10% and S2-20%.

The samples prepared by strategy 2 were then investigated by XRD to firstly check their components. Similar to the samples from strategy 1, typical TiO2 with an anatase phase was detected and no peak of NiO was observed due to a low content of NiO (Figure 3a). Nanocrystals can be identified from SEM images for both S2-10% and S2-20% (Figure 3b,c). Because of the low content of NiO, the obtained photocatalysts exhibited a light grey color. As crystalline TiO2 was used to prepare the composites, NiTiO3 can be avoided even at a high concentration of a nickel precursor. The dispersion and interaction between TiO2 and NiO were then investigated by TEM. The high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) showed a distinguishable nanocrystal of S2-20% (Figure 3d). The corresponding elemental mapping of Ti and Ni demonstrated a uniform distribution of NiO on TiO2, indicating the formation of uniform p-n heterojunction within the photocatalyst by strategy 2 (Figure 3e,f).

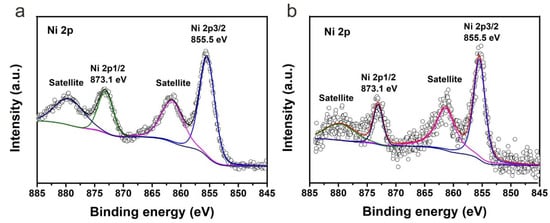

Due to the low content of NiO in S1 and S2, XRD did not show the typical peaks of NiO. To further demonstrate the chemical state of nickel in S1 and S2, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on samples S1-20% and S2-20%. The high-resolution XPS signal of Ni 2p was shown in Figure 4. It is clear that the Ni 2p spectrum of S1-20% has the same peak positions compared with that of S2-20%, indicating the chemical state of nickel in S1-20% and S2-20% is the same. Typical peaks at 855.5 eV and 873.1 eV corresponds to Ni 2p3/2 and Ni 2p1/2 respectively. The corresponding satellite peaks were also detected. The splitting energy of Ni 2p3/2 and Ni 2p1/2 is 17.6 eV, indicating the presence of nickel species is NiO rather than metallic nickel.

Figure 4. High-resolution XPS signal of Ni 2p of (a) S1-20% and (b) S2-20%.

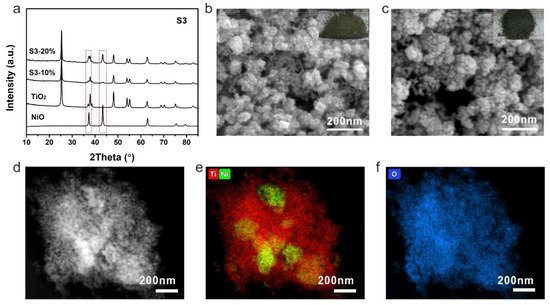

The samples prepared by strategy 3 were then investigated by XRD to check their components and crystallinity. Different from previous photocatalysts, the S3-10% and S3-20% showed typical diffusion peaks of NiO apart from the anatase TiO2 (Figure 5a). The intensities of NiO peaks were much higher of S3-20% than that of S3-10%, indicating a higher content of NiO in S3-20%. With high NiO loading, the color of NiO-TiO2 composites turned to black, which helps to improve the utilization of incident light. The morphology of S3-10% was quite different to that of the previous samples. A smooth surface of TiO2 nanocrystal changed to a rough surface due to the coverage of NiO on TiO2 and stick-like NiO can also be identified among the TiO2 nanocrystals (Figure 5b). The aggregation was more obvious with a higher NiO content (Figure 5c). Even though high NiO loading can be obtained by this method, the dispersion of NiO in the composite was revealed to be uneven. The NiO aggregation can clearly be observed by the HAADF-STEM and corresponding elemental mapping results (Figure 5d–f).

Figure 5. (a) XRD patterns, SEM images of (b) S3-10%, (c) S3-20%, (d) HAADF-STEM image of S3-20% and the corresponding elemental mapping (e) Ti (red), Ni (green) and (f) O (blue). Insets are the corresponding photographs of S3-10% and S3-20%.

References

- Schneider, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Zhang, J.L.; Horiuchi, Y.; Anpo, M.; Bahnemann, D.W. Understanding TiO2 photocatalysis: Mechanisms and materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986.

- Kubacka, A.; Fernandez-Garcia, M.; Colon, G. Advanced nanoarchitectures for solar photocatalytic applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1555–1614.

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38.

- Kudo, A.; Miseki, Y. Heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 253–278.

- Maeda, K.; Domen, K. Photocatalytic water splitting: Recent progress and future challenges. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 2655–2661.

- Dinh, C.T.; Yen, H.; Kleitz, F.; Do, T.O. Three-dimensional ordered assembly of thin-shell Au/TiO2 hollow nanospheres for enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6618–6623.

- Zhang, L.J.; Li, S.; Liu, B.K.; Wang, D.; Xie, T.F. Highly efficient CdS/WO3 photocatalysts: Z-scheme photocatalytic mechanism for their enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution under visible light. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 3724–3729.

- Wang, G.M.; Yang, X.Y.; Qian, F.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, Y. Double-sided CdS and CdSe quantum dot co-sensitized ZnO nanowire arrays for photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1088–1092.

- Sun, S.M.; Wang, W.Z.; Li, D.Z.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, D. Solar light driven pure water splitting on quantum sized BiVO4 without any cocatalyst. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 3498–3503.

- Kato, H.; Asakura, K.; Kudo, A. Highly efficient water splitting into H2 and O2 over lanthanum-doped NaTaO3 photocatalysts with high crystallinity and surface nanostructure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 3082–3089.

- Sathish, A.; Viswanath, R.P. Photocatalytic generation of hydrogen over mesoporous CdS nanoparticle: Effect of particle size, noble metal and support. Catal. Today 2007, 129, 421–427.

- Holmes, M.A.; Townsend, T.K.; Osterloh, F.E. Quantum confinement controlled photocatalytic water splitting by suspended CdSe nanocrystals. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 371–373.

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, C.; Ma, Z.; Ren, Z.; Fan, H.; Yang, X. Elementary photocatalytic chemistry on TiO2 surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 3701–3730.

- Ge, M.Z.; Cao, C.Y.; Huang, J.Y.; Li, S.H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, K.Q.; Al-Deyab, S.S.; Lai, Y.K. A review of one-dimensional TiO2 nanostructured materials for environmental and energy applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 6772–6801.

- Park, H.; Kim, H.I.; Moon, G.H.; Choi, W. Photoinduced charge transfer processes in solar photocatalysis based on modified TiO2. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 411–433.

- Moniz, S.J.A.; Shevlin, S.A.; Martin, D.J.; Guo, Z.X.; Tang, J.W. Visible-light driven heterojunction photocatalysts for water splitting—A critical review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 731–759.

- Zhao, H.; Yu, X.; Li, C.-F.; Yu, W.; Wang, A.; Hu, Z.-Y.; Larter, S.; Li, Y.; Golam Kibria, M.; Hu, J. Carbon quantum dots modified TiO2 composites for hydrogen production and selective glucose photoreforming. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 64, 201–208.

- Zhao, H.; Liu, P.; Wu, X.; Wang, A.; Zheng, D.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Larter, S.; Li, Y.; Su, B.-L.; et al. Plasmon enhanced glucose photoreforming for arabinose and gas fuel co-production over 3DOM TiO2-Au. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 291, 120055.

- Zhao, H.; Li, C.F.; Hu, Z.Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Chen, L.H.; Su, B.L. Size effect of bifunctional gold in hierarchical titanium oxide-gold-cadmium sulfide with slow photon effect for unprecedented visible-light hydrogen production. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 604, 131–140.

- Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.H.; Guo, W.B.; Qiu, J.C.; Mou, X.N.; Li, A.X.; Claverie, J.P.; Liu, H. NiO-TiO2 p-n heterostructured nanocables bridged by zero-bandgap rGO for highly efficient photocatalytic water splitting. Nano Energy 2015, 16, 207–217.

- Rawool, S.A.; Pai, M.R.; Banerjee, A.M.; Arya, A.; Ningthoujam, R.S.; Tewari, R.; Rao, R.; Chalke, B.; Ayyub, P.; Tripathi, A.K.; et al. pn heterojunctions in NiO:TiO2 composites with type-II band alignment assisting sunlight driven photocatalytic H2 generation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 221, 443–458.

- Ren, X.; Gao, P.; Kong, X.; Jiang, R.; Yang, P.; Chen, Y.; Chi, Q.; Li, B. NiO/Ni/TiO2 nanocables with Schottky/p-n heterojunctions and the improved photocatalytic performance in water splitting under visible light. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 530, 1–8.

- Lin, Z.Y.; Du, C.; Yan, B.; Wang, C.X.; Yang, G.W. Two-dimensional amorphous NiO as a plasmonic photocatalyst for solar H2 evolution. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4036.

- Uddin, M.T.; Nicolas, Y.; Olivier, C.; Jaegermann, W.; Rockstroh, N.; Junge, H.; Toupance, T. Band alignment investigations of heterostructure NiO/TiO2 nanomaterials used as efficient heterojunction earth-abundant metal oxide photocatalysts for hydrogen production. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 19279–19288.

- Kamegawa, T.; Kim, T.H.; Morishima, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Anpo, M. Preferential oxidation of CO impurities in the presence of H2 on NiO-loaded and unloaded TiO2 photocatalysts at 293 K. Catal. Lett. 2009, 129, 7–11.

- Chen, S.F.; Zhang, S.J.; Liu, W.; Zhao, W. Preparation and activity evaluation of p-n junction photocatalyst NiO/TiO2. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 155, 320–326.

- Chockalingam, K.; Ganapathy, A.; Paramasivan, G.; Govindasamy, M.; Viswanathan, A. NiO/TiO2 nanoparticles for photocatalytic disinfection of bacteria under visible light. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 2499–2505.

- Zhao, H.; Li, C.F.; Liu, L.Y.; Palma, B.; Hu, Z.Y.; Renneckar, S.; Larter, S.; Li, Y.; Kibria, M.G.; Hu, J.; et al. n-p Heterojunction of TiO2-NiO core-shell structure for efficient hydrogen generation and lignin photoreforming. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 585, 694–704.

- Li, M.-W.; Yuan, J.-P.; Gao, X.-M.; Liang, E.-Q.; Wang, C.-Y. Structure and optical absorption properties of NiTiO3 nanocrystallites. Appl. Phys. A 2016, 122, 725.

More

Information

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.4K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

19 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No