| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Litvaitis | + 2250 word(s) | 2250 | 2021-10-26 05:22:19 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | -59 word(s) | 2191 | 2021-12-01 05:20:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

Public lands alone are insufficient to address the needs of most at-risk wildlife species in the U.S. As a result, a variety of voluntary incentive programs have emerged to recruit private landowners into conservation efforts that restore and manage the habitats needed by specific species. There is one of such effort, Working Lands for Wildlife (WLFW), initiated by the Natural Resources Conservation Service in partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

1. Introduction

As human populations and their influence expand, the challenge of maintaining adequate habitat for species that are threatened with extinction has become urgent. In the United States, just over 13% of the terrestrial land area is protected (e.g., designated as national parks, wilderness areas, permanent conservation easements, state parks, national wildlife refuges, and national monuments) [1]. As a result, privately owned lands are especially important when addressing the needs of at-risk taxa because these lands support populations of more than two-thirds of the species listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, with 10% of the listed species occurring only on private lands [2]. Additionally, hundreds of species that are in documented declines occur on private lands [2]. Because rates of habitat destruction within the range of imperiled species are greater on private lands than protected lands [3], it is clear that efforts to maintain at-risk taxa require working on both public and privately owned lands [4][5][6][7].

Although some landowners consider their conservation responsibilities as a priority [8][9], others may perceive wildlife as a liability [10]. Because economic concerns affect decisions made by private landowners, incentive programs have been developed by state and federal agencies or non-governmental organizations to encourage landowner participation in conservation actions. These programs are intended to benefit a range of taxa from popular game species to at-risk plants and animals. They include monetary grants, cost sharing, incentive payments, rental contracts, and conservation easement purchases [2]. Grants or cost-share programs pay all or part of the costs associated with restoration or enhancement of habitats for specific species or communities. For example, a cost-share program in the state of Wisconsin provides funds to landowners to manage, restore, and preserve woodlands, savannah, wetlands, and prairie. That program provides funds for the cost of labor for prescribed burning, as well as in-kind materials, such as burning equipment and grass seed. A 10-year commitment is made by participating landowners, and the cost-share funds come from the sale of turkey and pheasant hunting permits purchased by hunters [11].

At the national level, several agencies are involved with the conservation of important vegetation communities on private lands. The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) was established over 80 years ago as the Soil Conservation Service to address soil conservation needs in response to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Today, the NRCS works with private landowners to conserve soil, water, air, plants, and animals that contribute toward productive lands and healthy ecosystems [12]. In 2012, NRCS and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) developed a partnership to provide long-term predictability in regulation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners who voluntarily participate in Working Lands for Wildlife (WLFW) projects [12]. Specifically, participating landowners in WLFW are in compliance with ESA regulations as long as they follow their NRCS-approved conservation plans.

A substantial portion of the needed funds is provided through the U.S. Farm Bill, legislation that covers most federal government policies related to agriculture in the United States. Conservation programs within the Farm Bill are the largest single federal source of funding for private land conservation. It is renewed approximately every 5 years [13], and support for conservation efforts on private lands has grown. The 1985 Farm Bill included the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which provided rental payments and cost-share assistance to establish grass or tree cover on environmentally sensitive croplands. Following the passage of the 2002 Farm Bill, the Conservation Effects Assessment Project (CEAP) was created by multiple agencies within the USDA to document the benefits of conservation practices and programs and to provide the science and education base needed for effective planning, implementation, management decisions, and policy [14]. In the 2018 Farm Bill, funding for the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), the primary program for funding conservation practices on working lands, increased to $9.2 billion for the years 2019 to 2023, with the expressed goal of maximizing the environmental benefits of conservation funding [15]. In the 2018 Farm Bill, WLFW was codified by the U.S. Congress as a permanent mechanism of the NRCS for directing EQIP and other Farm Bill program funds toward strategic conservation initiatives. WLFW is not a funded program itself; instead, it is an approach used to target and measure both outputs (e.g., area affected) and outcomes (e.g., threats mitigated or species recovered) across landscapes using Farm Bill funds and NRCS staff expertise. Initial efforts were targeted to benefit specific at-risk species [2]. So far, WLFW projects have affected more than 4 million hectares in 48 states [16].

2. Case Studies

Rather than delay recovery until a listing decision was made, several governmental (USFWS, NRCS, and state fish and wildlife agencies within the current range of the NEC) and non-governmental organizations initiated efforts to restore and expand habitats for NECs [17] and prepared a conservation strategy [18]. These efforts included plans to systematically develop and maintain habitat for NECs on public and private lands [18], and were considered sufficient enough that in 2015, the USFWS decided not to list the NEC as threatened or endangered under the ESA [19].

Once a landowner’s goals and objectives are clear, next comes the discussion of funding. Although landowners are willing to host a project on their property, they are generally unwilling to spend their own money on implementation. The NRCS provides financial assistance based on various metrics, especially the size of the area being managed. Cost-share payments from the NRCS to landowners enrolled in NEC projects are typically 75% or 90% of the project costs and cover actions that promote early-successional vegetation (e.g., brush mowing, tree removal, and herbicide treatments). Where landowners are unwilling to pay for the costs, matching grants are often necessary and are brought in by a third party.

To understand the drivers of population decline and develop a conservation strategy, a group of government agencies, conservation organizations, and academics formed the Golden-winged Warbler Working Group in 2004. This group prepared a status review and conservation plan [20] that included three primary goals: (a) increase the range-wide breeding habitat by 400,000 hectares, (b) stabilize the Appalachian Mountains population by doubling the number of breeding adults, and (c) grow the range-wide population by 50% by 2050. The plan also identified focal areas for implementing vegetation management. Focal areas are defined as places where the maintenance of core breeding populations will be important for sustaining and expanding the species’ current distribution, and their boundaries were delineated based on expert opinion, remote sensing data (elevation and percent forest cover), and distance to blue-winged warbler breeding populations. At the same time, habitat management guidelines were developed to provide landowners and managers with descriptions of actions for creating and enhancing habitats for golden-winged warbler (GWW) [20][21][22].

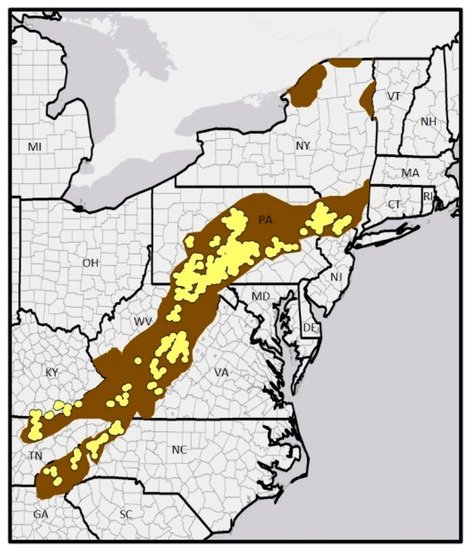

In 2012, the inclusion of the GWW by the NRCS as one of nine target species for the WLFW partnership added considerable funding and momentum toward efforts on private lands in several Appalachian states ( Figure 1 ). Landowners interested in participating in the WLFW GWW program first contacted their local NRCS office to determine if their property met the general requirements for enrollment in the initiative (i.e., it fell within the initiative’s boundary and was within a local landscape dominated by forest cover). If a property met these initial screening criteria, a partner forester and/or biologist conducted a site visit to discuss the landowner’s stewardship objectives and to identify areas that have potential for habitat management. If it was determined that a property was a good fit for the WLFW GWW program, the landowner completed an NRCS application which included a conservation plan that was prepared by the partner staff. All applications for a given fiscal year are ranked based on a set of criteria that considers each application’s potential for success. The NRCS provides cost-share funding to the highest ranked applications until all available funding has been obligated.

3. Management of Working Lands for Wildlife (WLFW)

Although several species aided by WLFW projects have been or are currently being considered for listing under the ESA (including GWW), this is not a requirement for WLFW support. Listed species have waited a median of 12.1 years to receive ESA protection [23]. Notably, NEC were first listed as a candidate for listing in 1989 and it was not until 2015 that the USFWS decided not to list them as threatened or endangered, largely because of the recovery efforts that were initiated by the partners and WLFW several years earlier.

WLFW was originally established to focus on large-scale conservation challenges based on a suite of target species that either already had ESA status or were at some risk of being listed as threatened or endangered. Over time, WLFW has expanded to include other species (e.g., the northern bobwhite quail, Colinus virginianus ) with well-documented habitats and population declines but no ESA implications, and has shifted its emphasis from single target species to a greater emphasis on restoring at-risk ecosystems such as native grasslands and the wildlife communities at large therein. As a result, monitoring and outcome assessments include tracking single-species responses as well as landscape-wide effects.

Nonetheless, quantifying the responses by target species remains a valuable metric beyond amount of land enrolled, as it provides the conservation community an understanding of the extent to which WLFW contributes to achieving population goals and addressing regulatory considerations. Acknowledging the difficulties of monitoring does not dismiss the need for improvement. Collaborative monitoring of management activities and their outcomes among landowners, NRCS personnel, and research scientists could establish information feedback loops between actions taken and conservation outcomes, and subsequently improve outcomes [24]. Although it was not the focus of this study, WLFW also conducts outcomes assessments for the economic impacts of the initiatives on landowners and communities, and this dual focus is key to the conservation of working lands conducted by the NRCS and its partners.

Landowners' experiences with conservation programs are important in affecting management outcomes [25][26]. Among the landowners involved in the GWW initiative, those who interacted with monitoring technicians in the field showed a greater level of agency trust than those landowners who did not interact with monitoring technicians [27], suggesting that personnel interactions could bolster program enrollment. Surprisingly, the presence of GWWs had a negative effect on continued management, suggesting that results for the target species may have been outweighed by broader landowner priorities for participation in conservation programs. This is not unusual or to be lamented, as developing a shared vision with landowners is not dependent on shared motivations. Beyond wildlife, other benefits (e.g., enhancing forest health and scenery) could affect landowners’ behavior [28].

4. Conclusion

The contributions of WLFW projects for developing and protecting habitats for at-risk species have been substantial, and these efforts are usually nested within larger partnerships with agencies that track population trends as part of their mission. The NRCS itself does not set population goals or track population trends. Instead, the NRCS conducts broader assessments that document priority species’ use of implemented projects to meet basic habitat needs, measures and tracks ecosystem health, and assesses local economic benefits to gauge WLFW’s effectiveness. Recognizing and appealing to landowner motivations are essential toward developing good relationships. Having a shared vision with private landowners should aid in ensuring the longevity of conservation actions in agricultural or timbered landscapes.

WLFW is built upon a foundational philosophy of encouraging win–win solutions for producers (“Working Lands”) and target species (“For Wildlife”). The NRCS develops implementation plans based on threats, conservation actions, and habitat and population goals identified by integrated partnerships of state and federal agencies collaborating with non-government conservation organizations, university experts, and private landowners. WLFW initiative partners strive to incorporate principles from existing conservation frameworks designed to achieve multiple objectives for wildlife, natural resources, and humans (e.g., [29]). In our examples, the conservation strategy for the New England cottontail and the golden-winged warbler's status assessment and conservation plan were developed by technical committees representing each target species' recovery needs. These existing conservation strategies were enhanced by monitoring and modeling to guide the delivery of WLFW [30] using many components of effective conservation planning (e.g., [29]). It cannot be overstated that well-funded conservation efforts such as WLFW have great potential for addressing resource concerns (i.e., forest health, water quality) and recovering declining wildlife populations, but the degree to which such programs are impactful, efficient, and sustained will largely be dependent upon the use of proven conservation frameworks and adaptive management.

References

- Protected Planet. Discover the world’s Protected Areas—United States of America. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/country/USA (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Baier, L.E. Saving Species on Private Lands—Unlocking Incentives to Conserve Wildlife and Their Habitats; Rowman & Littlefield: Lantham, MD, USA, 2020.

- Eichenwald, A.J.; Evans, M.J.; Malcom, J.W. US imperiled species are most vulnerable to habitat loss on private lands. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 18, 439–446.

- Knight, R.L. Private lands: The neglected geography. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 223–224.

- Kremen, C.; Merenlender, A.M. Landscapes that work for biodiversity and people. Science 2018, 362.

- Robles, M.D.; Flather, C.H.; Stein, S.M.; Nelson, M.D.; Cutko, A. The geography of private forests that support at-risk species in the conterminous United States. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 6, 301–307.

- Clancy, N.G.; Draper, J.P.; Wolf, J.M.; Abdulwahab, U.A.; Pendleton, M.C.; Brothers, S.; Brahney, J.; Weathered, J.; Hammill, E.; Atwood, T.B. Protecting endangered species in the USA requires both public and private land conservation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11925.

- Alexander, L.; Kellert, S.R. Forest landowners’ perspectives on wildlife management in New England. Trans. N. Am. Wildl. Nat. Resour. Conf. 1984, 49, 164–173.

- Daley, S.S.; Cobb, D.T.; Bromley, P.T.; Sorenson, C.E. Landowner attitudes regarding wildlife management on private land in North Carolina. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2004, 32, 209–219.

- Noonan, P.F.; Zagata, M.D. Wildlife in the market place: Using the profit motive to maintain wildlife habitat. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1982, 10, 46–49.

- Defenders of Wildlife. Conservation in America: State Government Incentives for Habitat Conservation: A Status Report. 2002. Available online: https://www.defenders.org/sites/default/files/publications/conservation_in_america.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Martinez, M. Working lands for wildlife: Targeted landscape-scale wildlife habitat conservation. Nat. Resour. Environ. 2015, 29, 36–39.

- Land Trust Alliance. Farm Bill Conservation Programs. 2018. Available online: https://www.landtrustalliance.org/topics/federal-programs/farm-bill-conservation-programs (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Duriancik, L.; Bucks, D.; Dobrowolski, J.; Drewes, T.; Eckles, S.; Jolley, L.; Kellogg, R.; Lund, D.D.; Makuch, J.R.; O’Neill, M.; et al. The first five years of the Conservation Effects Assessment Project. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2008, 63, 185A–197A.

- Natural Resources Conservation Service. Environmental Quality Incentives Program. Fed. Reg. 2020, 85, 67637–67648.

- Natural Resources Conservation Services. Supporting America’s Working Lands. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/programs/initiatives/?cid=stelprdb1046975 (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Arbuthnot, M. A Landowner’s Guide to New England Cottontail Habitat Management. Environmental Defense Fund. Available online: http://apps.edf.org/documents/8828_New-England-Cottontail-Guide.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2013).

- Fuller, S.; Tur, A. Conservation Strategy for the New England Cottontail (Sylvilagus Transitionalis). Available online: http://www.newenglandcottontail.org/sites/default/files/research_documents/conservation_strategy_final_12-3-12.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2013).

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; 12-month finding on a petition to list the New England cottontail as an endangered or threatened species. Fed. Reg. 2015, 80, 55286–55304.

- Roth, A.M.; Rohrbaugh, R.W.; Will, T.; Swarthout, S.B.; Buehler, D.A. (Eds.) Golden-Winged Warbler Status Review and Conservation Plan, 2nd ed. 2019. Available online: www.gwwa.org//wp-content/uploads/2020/06/GWWA_Conservation-Plan_191007_low-res.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Bakermans, M.H.; Smith, B.W.; Jones, B.C.; Larkin, J.L. Stand and within-stand factors influencing Golden-winged Warbler use of regenerating stands in the central Appalachian Mountains. Avian Conserv. Ecol. 2015, 10, 10.

- Bakermans, M.H.; Larkin, J.L.; Smith, B.W.; Fearer, T.M.; Jones, B.C. Golden-Winged Warbler Habitat Best Management Practices for Forestlands in Maryland and Pennsylvania; American Bird Conservancy: The Plains, Virginia, 2011; 26p.

- Puckett, E.E.; Kesler, D.C.; Greenwald, D.N. Taxa, petitioning agency, and lawsuits affect time spent awaiting listing under the US Endangered Species Act. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 201, 220–229.

- Briske, D.D.; Bestlemeyer, B.T.; Brown, J.R.; Brunson, M.W.; Thurow, T.L.; Tanka, J.A. Assessment of USDA-NRCS rangeland conservation programs: Recommendation for evidence-based conservation platform. Ecol. Appl. 2017, 27, 94–104.

- Selinske, M.J.; Coetzee, J.; Purnell, K.; Knight, A.T. Understanding the motivations, satisfaction, and retention of landowners in private land conservation programs. Conserv. Lett. 2015, 8, 282–289.

- Farmer, J.R.; Ma, Z.; Drescher, M.; Knackmuhs, E.G.; Dickinson, S.L. Private landowners, voluntary conservation programs, and implementation of conservation friendly land management practices. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 58–66.

- Lutter, S.H.; Dayer, A.A.; Heggenstaller, E.; Larkin, J.L. Effects of biological monitoring and results outreach on private landowner conservation management. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194740.

- Lutter, S.H.; Dayer, A.A.; Rodewald, A.D.; McNeil, D.J.; Larkin, J.L. Early successional forest management on private lands as a coupled human and natural system. Forest 2019, 10, 499.

- Schwartz, M.W.; Cook, C.N.; Pressey, R.L.; Pullin, A.S.; Runge, M.C.; Salafsky, N.; Sutherland, W.J.; Williamson, M.A. Decision support frameworks and tools for conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12385.

- Naugle, D.E.; Maestas, J.D.; Allred, B.W.; Hagen, C.A.; Jones, M.O.; Falkowski, M.J.; Randall, B.; Rewa, C.A. CEAP quantifies conservation outcomes for wildlilfe and people on western grazing lands. Rangelands 2019, 41, 211–217.