| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sébastien Menzinger | + 3955 word(s) | 3955 | 2021-08-27 07:34:31 | | | |

| 2 | Lily Guo | -1121 word(s) | 2834 | 2021-11-03 03:23:00 | | | | |

| 3 | Lily Guo | Meta information modification | 2834 | 2021-11-03 05:10:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

The term “pseudomalignancy” covers a large, heterogenous group of diseases characterized by a benign cellular proliferation, hyperplasia, or infiltrate that resembles a true malignancy clinically or histologically.

1. Introduction

The term “pseudomalignancy” covers a large, heterogenous group of diseases characterized by a benign cellular proliferation, hyperplasia, or infiltrate that resembles a true malignancy clinically or histologically. Several inflammatory skin diseases or benign skin proliferations in children can mimic malignant neoplasms [1]. However, when examining a child’s skin biopsy, the pathologist must bear in mind that benign disorders are more frequent than malignancies.

In this entry we provide a non-exhaustive review of several inflammatory skin diseases and benign skin proliferations that can mimic a malignant neoplasm in children, give pathologists some helpful clues to guide their diagnosis, and highlight pitfalls to be avoided. Here, we review cellular infiltrates of the skin that can mimic neoplasms of the skin in children. The article is divided into three subsections, according to the specific type of cellular infiltrate (lymphocytic, histiocytic, and melanocytic infiltrates).

2. Lymphocytic Infiltrates

Cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates that mimic lymphoma can be referred to cutaneous pseudolymphomas. This heterogenous group has been described in the literature as reactive lymphoproliferation that histopathologically and clinically imitates cutaneous lymphomas[2]. The causes are many and varied. Cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates can be subdivided as a function of the histological pattern or the predominant immunophenotype (T or B), amongst others.

Vitiligo

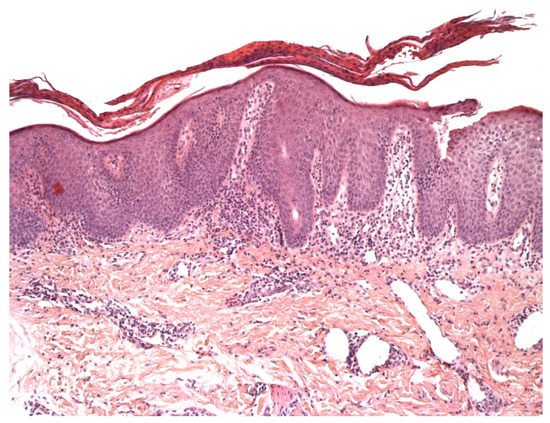

Vitiligo is an acquired chronic depigmentation disorder results from the selective destruction of melanocytes; although the etiology is unknown, an auto-inflammatory or auto-immune mechanism is most strongly suspected[3]. Clinical differentiation between vitiligo and MF in children can be challenging, especially because hypopigmented MF is particularly frequent in children with a darker skin type [4] and can clinically mimic vitiligo or other pathologies with hypopigmentation or depigmentation. In the early (inflammatory) phase of vitiligo, a marked superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate can be observed; it sometimes has a lichenoid pattern and can be mistaken for epidermotropism [1](Figure 1). Moreover, the intra-epidermal lymphocytes in inflammatory vitiligo are predominantly CD8-positive[2], as in hypopigmented MF[2][3]. Some features tend to indicate a diagnosis of hypopigmented MF: partial depigmentation, the persistence of some melanocytes, wiry fibrosis of the papillary dermis, and increased density of the dermal infiltrate. When observed, the loss of cell surface “pan-T” antigens (CD2, CD5, and CD7) and the presence of clonal T-cell receptor rearrangements may be of diagnostic value. In difficult cases, the observation of clinical-pathological correlations and the course of the disease should enable a definitive diagnosis.

Pityriasis lichenoides

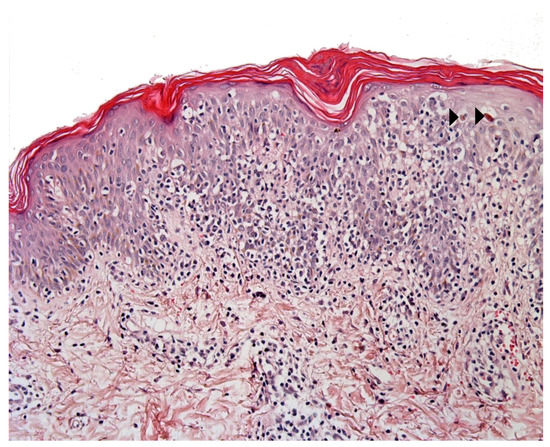

Pityriasis lichenoides (PL) is an infrequent skin disorder that predominantly affects children and young adults. The clinical presentation usually differs from that of MF, although the histological picture can be very similar. Moreover, PL can be present before (or at the same time as) MF in children. The histological picture in PL usually includes parakeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, variable numbers of necrotic keratinocytes, interface changes with prominent lymphocytic exocytosis, perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates in the superficial and deep dermis, and red blood cell extravasation[4]. However, some cases present with prominent intra-epidermal lymphocytes, basal cell replacement by lymphocytes, and nuclei surrounded by a clear halo - as in MF (Figure 2). The immunohistochemical findings are not usually helpful, unless “pan-T” antigen (CD2, CD5, and CD7) loss is highlighted. Moreover, a screen for monoclonality is not very helpful because many PL cases show a clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement [5][6]. Some findings tend to indicate a diagnosis of PL: the presence of necrotic keratinocytes, superficial epidermal pallor, red blood cell extravasation (especially intra-epidermal extravasation), and the presence of deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates.

Scabies nodules and insect bite reactions

The histological features of insect bite reactions (including scabies and post-scabies nodules) may mimic those of LyP, with a dense, lymphoid, wedge-shaped infiltrate containing large numbers of eosinophils and atypical or large CD30+ lymphoid cells[8][9]. The presence of CD30+ large lymphoid cells is a feature of many infectious diseases of the skin and is considered to be a sign of lymphocyte activation[10]. CD30 is a member of the tumor necrosis factor super-family and probably has a role in the immune response to infections[11]. In LyP in children, the high eosinophil count can mask the presence of large, atypical lymphocytes. A screen for monoclonality may help in some cases. Clinical-histological correlations, and sometimes additional biopsies and/or response to empiric therapy, are often the only means of making a firm diagnosis[12].

Lymphoplasmacytic plaque and Acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma of children

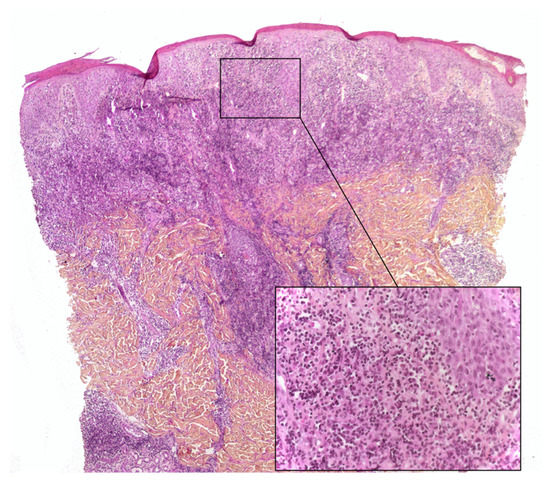

Lymphoplasmacytic plaque (LPP) is a rare, recent characterized clinicopathological entity that mostly affects children. It features an asymptomatic, linear, reddish-brown, violaceous plaque, usually on the leg - hence the name “tibial” or “pretibial” LPP[13][14]. Since the initial reports, however, cases affecting other parts of the body have been described[15]. The histopathology is characterized by a dense nodular infiltrate within the upper reticular dermis or the whole dermis. This infiltrate is an admixture of plasma cells, lymphocytes, scattered histiocytes and (in some cases) epithelioid granulomas, together with vascular hyperplasia. The overlying epidermis may be hyperplastic and spongiotic[13][16] (Figure 3). Importantly, the histological presentation of LP can be confused with that of cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma, a low-grade B cell lymphoma that very rarely affects children and occasionally affects teenagers[17]. Immunohistochemical analysis of the plasma cells in LPP shows a polytypic pattern of immunoglobulin light chain expression, and PCR studies do not show monoclonality[14][16][18].

This disease is closely related to another pseudolymphomatous disorder called “acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma of children” (APACHE) and may be a part of the same spectrum is a rare disease with female predominance[19]. It is characterized clinically by unilateral, asymptomatic, erythematous-violaceous papules and nodules with an acral distribution[20]. The histology findings are characterized by a dense superficial and deep dermal infiltrate, and a prominent vascular pattern of capillaries lined with plump endothelial cells. The infiltrate comprises lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils. The epidermis may also show hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, and lymphocyte exocytosis[20]. Immunohistochemical studies show a slight predominance of T lymphocytes (with equal numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ cells, or slightly more CD4+ cells) and a large number of B lymphocytes. To the best of our knowledge, the presence or absence of CD30 in APACHE has not been studied immunohistochemically. A PCR analysis reveals that APACHE is a polyclonal disorder[21][22].

3. Histiocytic Infiltrates

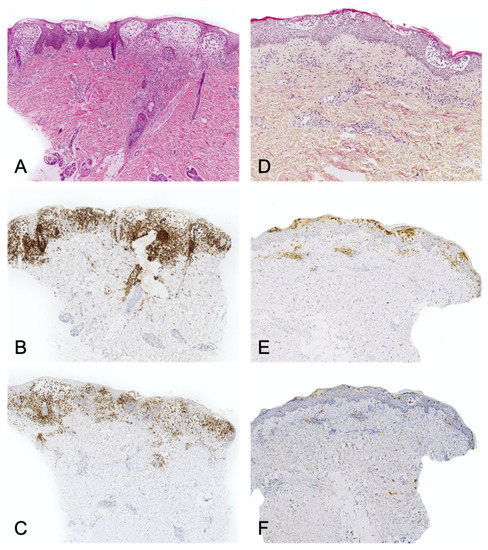

CD1a+ dendritic cell hyperplasia

CD1a+ dendritic cell hyperplasia (CD1a+ DCH) has been described in children as part of a large number of disorders including scabies, arthropod bite reactions, prurigo, warts, molluscum contagiosum, spongiotic dermatoses, psoriasis, PL, and interface dermatitis[23][24][25]. CD1a+ DCH can also be observed in proliferative processes, such as regressive melanocytic nevi, lymphoproliferative disorders, and the stroma of various tumors[26] [27]. The CD1a+ DCH may have the typical aspect of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), i.e. round, medium-sized histiocytes with eosinophilic cytoplasm and, in some cases, large reniform or “coffee bean” shaped nuclei. This LCH-mimicking phenomenon is often referred to as “Langerhans cell hyperplasia” and can lead to misdiagnosis. There are a few histological features that facilitate the differential diagnosis between CD1a+ DCH and LCH:

- the infiltrate’s architecture: in CD1a+ DCH, cells are mostly located around the vessels in the dermis and do not accumulate in the papillary dermis as in LCH.

- the infiltrate’s polymorphism: the CD1a+ cells are rarely predominant and are mixed with other cell types.

- immunoreactivity: importantly, the cells are not true Langerhans cells because they do not usually express CD207 (Langerin); in fact, they are CD1a+/CD207- dendritic cells that lack Birbeck granules[23][28]. CD207 is a very sensitive, specific marker of Birbeck granules, which are located in the cytoplasm of Langerhans cells. (Figure 4).

Juvenile xanthogranuloma

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is the most frequent subtype of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis and one of the commonest skin tumors in children. This benign disorder usually affects young children and typically presents as a single erythematous to yellow papule, nodule or plaque in the head and neck area. JXG usually regresses spontaneously and is very rarely associated with systemic disease[29]. Most JXG lesions appear during the first few years of life. It can mimic sarcoma in general and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans in particular. Accordingly, a biopsy is essential. The neonatal cases of JXG can also mimic malignancies histologically, since they usually display a large number of mitotic figures and have a high mitotic index (Ki67). Furthermore, early-stage JXG does not show xanthomization, and the cells tend to be monomorphous or even spindled. Early-stage JXG may also lack granulomatous inflammatory cells and thus can mimic spindle-cell sarcoma, round-cell sarcoma, or monoblastic leukemia. However, the cells do not show marked atypia and are commonly CD163+ and FXIIIa+ – at least focally.

4. Melanocytic disorders

Melanoma is rare in children; it accounts for 3% of all pediatric cancers. Both sexes are affected equally. Although 2% of melanomas occur in patients under the age of 20, only 0.3% occur in prepubertal children.

A number of common but histologically ambiguous melanocytic lesions can easily be misconstrued as melanoma; they include (i) Spitz nevus and its variants, (ii) proliferative nodules in congenital nevi, (iii) acquired melanocytic nevi on particular, “special” anatomic sites (such as the scalp, genital area, acral sites and conjunctiva), and (iv) lesions on the blue nevus spectrum[30].

Melanocytic lesions in newborns

Melanoma is very rare in the neonatal period. The tumor either arises in a giant congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN) or grows from transplacental metastases of the mother’s melanoma[31][32]. The estimated risk of developing a melanoma associated with CMN is between 1 and 2% but might be as high as 10 to 15% for large and giant CMN.

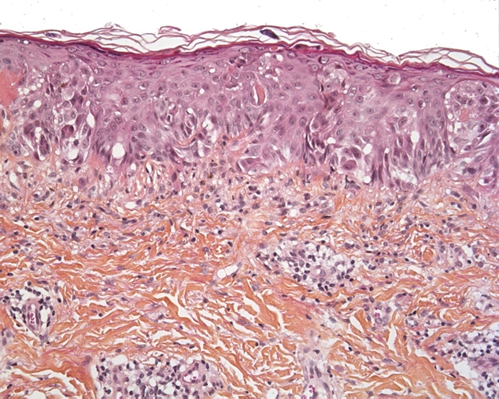

Melanocytic lesions in newborns can show worrisome histological features. The junctional component may show irregularly distributed and sometimes non cohesive nests. Pagetoid spread (a helpful criterion in the diagnosis of adult melanoma) should be interpreted with caution because it is displayed by many melanocytic lesions in newborns[30] and can therefore mimic superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) (Figure 5). The lesions may also be nodular and ulcerated, with many mitotic figures and a high proliferation index (Ki67/ MIB); it can therefore mimic nodular melanoma. These lesions must be interpreted carefully so that melanoma is not erroneously diagnosed in this population. Ancillary immunochemistry or molecular biology test can be helpful (see the following section). Ideally, the clinician should seek an expert opinion before diagnosing melanoma. If doubt persists, excision of the lesion with broad margins (if possible) and long-term follow-up is recommended.

Figure 5. Junctional component of a congenital nevus in a newborn. Irregularly distributed melanocytes with pagetoid spread. HE x 250.

Figure 5. Junctional component of a congenital nevus in a newborn. Irregularly distributed melanocytes with pagetoid spread. HE x 250.

Melanocytic lesions associated with a congenital melanocytic nevus

A distinct, benign, nodular proliferation arising on a congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN) and particularly on a giant CMN is referred to as a “proliferative nodule” (PN). This entity is relatively common and can mimic the clinical and histological features of melanoma[33]. The cell density is higher in the PN than in the adjacent congenital nevus. A PN can sometimes exhibit worrisome clinical features, such as rapid growth or ulceration. The typical histological characteristics of melanoma can also be seen in PN; these include a high mitotic index, sheets of large melanocytes with an epithelioid morphology, nuclear atypia, and even atypical mitoses and necrosis(34). The features of this kind of lesion must be interpreted with caution because large/giant CMN is nevertheless the main risk factor for the development of melanoma in childhood[35][36].

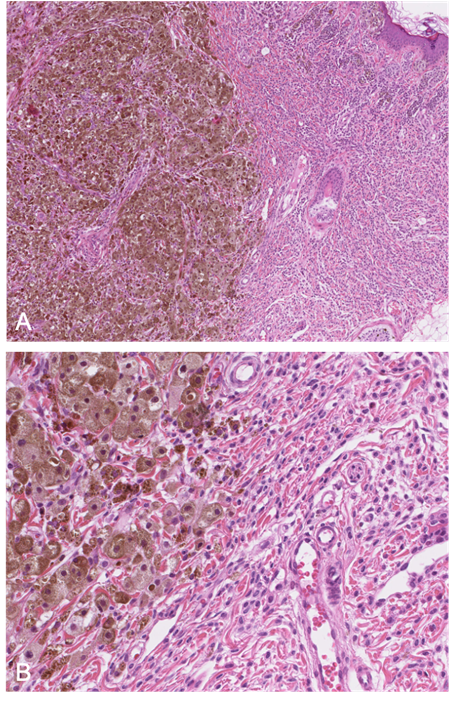

Several subtypes or morphological patterns have been described, including epithelioid, Spitzoid, small round blue cell-like, blue nevus-like, nevoid melanoma-like, and complex subtypes[34]. The recent literature has provided many characteristics, features and clues of value in distinguishing between melanoma and PN[34][37][38]. The first important observation is that PN is much more frequent than melanoma. Secondly, and in contrast to melanoma, PN presents frequently as multiple lesions. Ulceration is suggestive of melanoma, especially when extensive. Blending (i.e. a smooth transition between PN cells and nevus cells), favors PN, even when focal (Figure 6). However, this feature is not always observed, and its significance is subject to debate. A very high mitotic index, necrosis within the nodule, inflammation, pleomorphism, and high-grade atypia increase the likelihood of a diagnosis of melanoma[32]. Ancillary tests, such as immunochemistry and molecular assays (FISH, CGH) are sometimes of diagnostic value.

Figure 6. A: (HE x 40) Proliferative nodule in a congenital melanocytic lesion. B: (HE x 250) The melanocytes of the proliferative nodule are epithelioid and with a dusty cytoplasm, without nuclear atypia. Note the delicate transition (blending), which may be very focal and unconspicuous.

Figure 6. A: (HE x 40) Proliferative nodule in a congenital melanocytic lesion. B: (HE x 250) The melanocytes of the proliferative nodule are epithelioid and with a dusty cytoplasm, without nuclear atypia. Note the delicate transition (blending), which may be very focal and unconspicuous.

Juvenile nevi

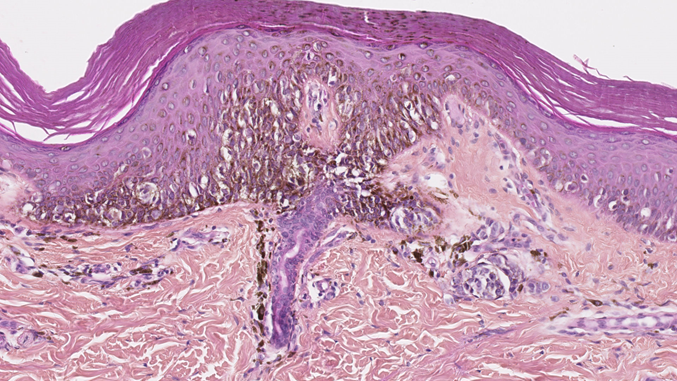

In principle, SSM does not occur in prepubertal children. However, common, acquired “juvenile-type” nevi occasionally show worrisome histological features that mimic SSM. Most of these lesions present as epithelioid Spitz nevi with a predominantly epithelioid appearance characterized by enlarged round-to-oval nuclei, often with a delicate open chromatin pattern. Some lesions are flat but some may be polypoid. These “juvenile-type” nevi may contain suprabasal intraepidermal melanocytes - especially in young children. At most one can see features of “pagetoid Spitz nevus”, with the prominent pagetoid growth of solitary units and nests of melanocytes in the stratum spinosum throughout the lesion (Figure 7). Care must be taken not to confuse a pagetoid Spitz nevus with in situ melanoma. The presence of Spitzoid cytologic features, a small lesion diameter, and sharp demarcations are important parameters for the diagnosis of a Spitz nevus rather than SSM[39].

Figure 7. Pagetoid Spitz nevus (HE x 250). Epithelioid or spindle melanocytes with large nuclei and abundant “ground glass” cytoplasm, and pagetoid spread.

Figure 7. Pagetoid Spitz nevus (HE x 250). Epithelioid or spindle melanocytes with large nuclei and abundant “ground glass” cytoplasm, and pagetoid spread.

Spitz nevus and atypical Spitz tumor

Spitz nevus and Spitzoid melanocytic lesions are part of a spectrum of melanocytic proliferations with a distinctive cellular morphology. The clinical-pathologic classification, diagnosis, and management of these lesions are among the most problematic topics in dermatopathology[40].

Histologically, Spitz nevi are mainly compound nevi and consist of epithelioid and spindle melanocytes with large nuclei and abundant “ground glass” cytoplasm. They show symmetry, sharp demarcation, uniform maturation (zonation), epidermal hyperplasia, Kamino bodies, no pleomorphism, no high-grade atypia, few mitoses, no mitoses in deep tissue, and no subcutaneous tissue involvement.

Some Spitzoid lesions present atypia and are therefore referred to as an “atypical Spitz nevi” or “atypical Spitz tumors”. These atypia include a diameter >10 mm, asymmetry, subcutaneous fat involvement, a “pushing” deep margin, ulceration, poor demarcation, pagetoid migration, lack of maturation and zonation, few or no Kamino bodies, a high mitotic index (>2-6/mm2), deep mitoses, a proliferation index ≥10%, and cytological atypia (e.g. a high nucleocytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromatism, and large nucleoli)[41][42].

5. Conclusion

Many skin conditions in children can mimic the clinical and histologic features of malignancies. The pathologist must bear in mind that a neoplasm in a young child (and especially a newborn) will frequently have a high mitosis count or mitotic index, which are usually indicative of malignancy in adults. All dermatologists and dermatopathologists are aware of the importance of clinical-pathological correlations. This is particularly true in pediatrics, and these correlations - along with careful monitoring of the disease’s clinical course – sometimes constitute the only means of reaching a firm diagnosis. Except during the neonatal period, cutaneous malignancies are very rare in children; hence, the clinician is more likely to make a false-positive diagnosis than to truly miss a malignant disorder. It is also very important to ask for a second opinion from an expert center, when indicated.

References

- Werner B, Brown S, Ackerman AB. “Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides” is not always mycosis fungoides! Am J Dermatopathol. 2005 Feb;27(1):56–67.

- Furlan FC, de Paula Pereira BA, da Silva LF, Sanches JA. Loss of melanocytes in hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a study of 18 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2014 Feb;41(2):101–7.

- Castano E, Glick S, Wolgast L, Naeem R, Sunkara J, Elston D, et al. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in childhood and adolescence: a long-term retrospective study. J Cutan Pathol. 2013 Nov;40(11):924–34.

- Menzinger S, Frassati-Biaggi A, Leclerc-Mercier S, Bodemer C, Molina TJ, Fraitag S. Pityriasis Lichenoides: A Large Histopathological Case Series With a Focus on Adnexotropism. Am J Dermatopathol. 2020 Jan;42(1):1–10.

- Dereure O, Levi E, Kadin ME. T-Cell clonality in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a heteroduplex analysis of 20 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000 Dec;136(12):1483–6.

- Weinberg JM, Kristal L, Chooback L, Honig PJ, Kramer EM, Lessin SR. The clonal nature of pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol. 2002 Aug;138(8):1063–7.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Palmedo G, Fraitag S, Schaerer L, Kutzner H. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta with numerous CD30(+) cells: a variant mimicking lymphomatoid papulosis and other cutaneous lymphomas. A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012 Jul;36(7):1021–9.

- Cepeda LT, Pieretti M, Chapman SF, Horenstein MG. CD30-positive atypical lymphoid cells in common non-neoplastic cutaneous infiltrates rich in neutrophils and eosinophils. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003 Jul;27(7):912–8.

- Hwong H, Jones D, Prieto VG, Schulz C, Duvic M. Persistent atypical lymphocytic hyperplasia following tick bite in a child: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001 Dec;18(6):481–4.

- Gallardo F, Barranco C, Toll A, Pujol RM. CD30 antigen expression in cutaneous inflammatory infiltrates of scabies: a dynamic immunophenotypic pattern that should be distinguished from lymphomatoid papulosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2002 Jul;29(6):368–73.

- Marín ND, García LF. The role of CD30 and CD153 (CD30L) in the anti-mycobacterial immune response. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2017 Jan;102:8–15.

- Miquel J, Fraitag S, Hamel‐Teillac D, Molina T, Brousse N, Prost Y, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis in children: a series of 25 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):1138–46.

- Moulonguet I, Hadj-Rabia S, Gounod N, Bodemer C, Fraitag S. Tibial lymphoplasmacytic plaque: a new, illustrative case of a recently and poorly recognized benign lesion in children. Dermatology. 2012;225(1):27–30.

- Bierbrier RM, Amdemichael E, Adam DN. Pretibial Lymphoplasmacytic Plaque in Children: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019 Apr;41(4):300–2.

- Tsilika K, Montaudié H, Castela E, Cardot‐Leccia N, Passeron T, Lacour J ‐P. A case of lymphoplasmacytic plaque in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol [Internet]. 2019 Apr [cited 2021 Mar 21];33(4). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jdv.15408

- Moulonguet I, Gantzer A, Bourdon-Lanoy E, Fraitag S. A pretibial plaque in a five and a half year-old girl. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012 Feb;34(1):113–6.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Buechner SA, Graf M, Zettl A, Zimmermann DR, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma in children: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014 Aug;36(8):661–6.

- Fried I, Wiesner T, Cerroni L. Pretibial lymphoplasmacytic plaque in children. Arch Dermatol. 2010 Jan;146(1):95–6.

- Tokuda Y, Arakura F, Murata H, Koga H, Kawachi S, Nakazawa K. Acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma of children: a case report with immunohistochemical study of antipodoplanin antigen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012 Dec;34(8):e128-132.

- Lessa PP, Jorge JCF, Ferreira FR, Lira ML de A, Mandelbaum SH. Acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma: case report and literature review. An Bras Dermatol. 2013 Dec;88(6 Suppl 1):39–43.

- Hagari Y, Hagari S, Kambe N, Kawaguchi T, Nakamoto S, Mihara M. Acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma of children: immunohistochemical and clonal analyses of the infiltrating cells. J Cutan Pathol. 2002 May;29(5):313–8.

- Evans MS, Burkhart CN, Bowers EV, Culpepper KS, Googe PB, Magro CM. Solitary plaque on the leg of a child: A report of two cases and a brief review of acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma of children and unilesional mycosis fungoides. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Jan;36(1):e1–5.

- Bhattacharjee P, Glusac EJ. Langerhans cell hyperplasia in scabies: a mimic of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2007 Sep;34(9):716–20.

- Hatter AD, Zhou X, Honda K, Popkin DL. Langerhans Cell Hyperplasia From Molluscum Contagiosum. The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 2015 Aug;37(8):e93–5.

- Kim SH, Kim DH, Lee KG. Prominent Langerhans’ cell migration in the arthropod bite reactions simulating Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2007 Dec;34(12):899–902.

- Jokinen CH, Wolgamot GM, Wood BL, Olerud J, Argenyi ZB. Lymphomatoid papulosis with CD1a+ dendritic cell hyperplasia, mimicking Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2007 Jul;34(7):584–7.

- Ezra N, Van Dyke GS, Binder SW. CD30 positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma mimicking Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 2009 Oct 9;37(7):787–92.

- Drut R, Peral CG, Garone A, Rositto A. Langerhans cell hyperplasia of the skin mimicking Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a report of two cases in children not associated with scabies. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2010;29(4):231–8.

- Gianotti F, Caputo R. Histiocytic syndromes: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 Sep;13(3):383–404.

- Busam KJ, Scolyer RA, Gerami P. Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors E-Book [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 Jun 8]. Available from: https://nls.ldls.org.uk/welcome.html?ark:/81055/vdc_100063476428.0x000001

- Stefanaki C, Chardalias L, Soura E, Katsarou A, Stratigos A. Paediatric melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Oct;31(10):1604–15.

- Masson Regnault M, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Fraitag S. Les mélanomes d’apparition précoce (congénitaux, néonataux, du nourrisson) : revue systématique des cas de la littérature. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie. 2020 Nov;147(11):729–45.

- Pavlova O, Fraitag S, Hohl D. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine Expression in Proliferative Nodules Arising within Congenital Nevi Allows Differentiation from Malignant Melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Dec;136(12):2453–61.

- Yélamos O, Arva NC, Obregon R, Yazdan P, Wagner A, Guitart J, et al. A comparative study of proliferative nodules and lethal melanomas in congenital nevi from children. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015 Mar;39(3):405–15.

- Kinsler VA, O’Hare P, Bulstrode N, Calonje JE, Chong WK, Hargrave D, et al. Melanoma in congenital melanocytic naevi. Br J Dermatol. 2017 May;176(5):1131–43.

- Lacoste C, Avril M-F, Frassati-Biaggi A, Dupin N, Chrétien-Marquet B, Mahé E, et al. Malignant Melanoma Arising in Patients with a Large Congenital Melanocytic Naevus: Retrospective Study of 10 Cases with Cytogenetic Analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015 Jul;95(6):686–90.

- Aoyagi S, Akiyama M, Mashiko M, Shibaki A, Shimizu H. Extensive proliferative nodules in a case of giant congenital naevus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008 Mar;33(2):125–7.

- van Houten AH, van Dijk MCRF, Schuttelaar M-LA. Proliferative nodules in a giant congenital melanocytic nevus-case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2010 Jul;37(7):764–76.

- Busam KJ, Barnhill RL. Pagetoid Spitz nevus. Intraepidermal Spitz tumor with prominent pagetoid spread. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995 Sep;19(9):1061–7.

- Ferrara G, Gianotti R, Cavicchini S, Salviato T, Zalaudek I, Argenziano G. Spitz nevus, Spitz tumor, and spitzoid melanoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic overview. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):589–98, viii.

- Barnhill RL. The Spitzoid lesion: rethinking Spitz tumors, atypical variants, “Spitzoid melanoma” and risk assessment. Mod Pathol. 2006 Feb;19 Suppl 2:S21-33.

- Dika E, Ravaioli GM, Fanti PA, Neri I, Patrizi A. Spitz Nevi and Other Spitzoid Neoplasms in Children: Overview of Incidence Data and Diagnostic Criteria. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 Jan;34(1):25–32.