Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ajeet Kaushik | + 2198 word(s) | 2198 | 2021-11-01 05:27:52 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 246 word(s) | 2444 | 2021-11-04 08:38:24 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kaushik, A. Graphene-Based Biosensors to Detect Dopamine. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15591 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Kaushik A. Graphene-Based Biosensors to Detect Dopamine. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15591. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Kaushik, Ajeet. "Graphene-Based Biosensors to Detect Dopamine" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15591 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Kaushik, A. (2021, November 01). Graphene-Based Biosensors to Detect Dopamine. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15591

Kaushik, Ajeet. "Graphene-Based Biosensors to Detect Dopamine." Encyclopedia. Web. 01 November, 2021.

Copy Citation

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease in which the neurotransmitter dopamine (DA) depletes due to the progressive loss of nigrostriatal neurons. Therefore, DA measurement might be a useful diagnostic tool for targeting the early stages of PD, as well as helping to optimize DA replacement therapy. Moreover, DA sensing appears to be a useful analytical tool in complex biological systems in PD studies. Graphene-based DA sensors are emerging analytical tools for PD diagnostics.

dopamine

Parkinson’s disease

graphene

biosensing

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common human neurodegenerative disorder, after Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. The disease is diagnosed based on motor impairment, including bradykinesia rigidity or tremor; this is when about 70% of the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta are degenerated due to α-synuclein deposits. PD is also diagnosed clinically once the synucleinopathy is already advanced. Researchers and clinicians indicate a potential temporal window before the onset of specific signs and symptoms of the disorder during which potential disease-modifying therapy could be administered to prevent or delay the disease development and progression. Indeed, there is a need for an early diagnosis primarily based on quantifiable measures (i.e., biomarkers) to refine qualitative assessments [2]. From a neurochemical perspective, PD is a neurodegenerative disease in which depletion of the catecholamine DA in the nigrostriatal system appears due to the loss of nigral neurons and striatal terminals. Over the years, the neurotransmitter loss progresses to reach only 3% of normal DA concentration in the putamen of patients with pathologically proven end-stage PD. In untreated PD patients, most studies found significantly decreased DA levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), reflecting dopaminergic cell loss [3]. Eventually, an individual develops motor symptoms, including bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, and postural instability, which result from this drop in DA level. This means that DA level measurement might be a useful diagnostic tool for targeting the early stage of the defunctionalization of DA-producing neurons (nigrostriatal dopaminergic denervation) to enable the development of approaches to retard progression or even prevent the disease [4].

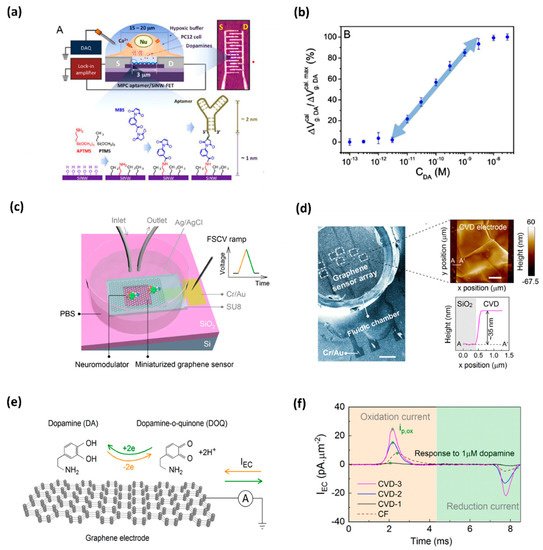

Due to high spatial and temporal resolution, high sensitivity and selectivity, and the possibility of direct monitoring at low cost and with the leverage of user-friendly tools, oxidation-based electrochemical sensing platforms are becoming a more popular and developed technique that is being implemented in a biological environment [5][6][7] and also for DA detection [8]. Efforts have been made to detect in situ DA, e.g., in the brain or living cells. Asif et al. applied the Zn-NiAl LDH/rGO superlattice electrode to track the DA released from human neuronal neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY-5Y [9]. Li et al. demonstrated a developed nanoelectronic biosensor, as shown in Figure 1, for monitoring the DA release from living PC12 cells [10]. Figure 1a shows the illustration of a DNA-aptamer modified by a multiple parallel-connected (MPC) silicon nanowire field-effect transistor (SiNW-FET) device, as well as the process of DNA-aptamer immobilization of the MPC SiNWFET. This device detects the DA under hypoxic stimulation from living PC12 cells. This developed MPC aptamer/SiNW-FET device demonstrated a DA detection limit of up to <10−6 M with high specificity when exposed to other chemicals, such as tyrosine, ascorbic acid (AA), phenethylamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and catechol. Wu et al. fabricated reproducible miniaturized, multi-layered, graphene-based sensors with astonishingly high sensitivity when compared with other sensors [11]. Figure 1b (i) shows the nanofabricated miniaturized multilayer graphene sensor electrodes. Figure 1b (ii) shows the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the top of the sensor array and the AFM image of the sensor surface. Figure 1b (iii) depicts the mechanism behind it. The DA undergoes a redox reaction and is oxidized to dopamine-o-quinone (DOQ) by applying voltage. The sensitivity of the fabricated sensor is monitored by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) measurements. Figure 1b (iv) displays the area-normalized electrochemical current (IEC) curves in response to the DA solution. The fabricated graphene sensor achieved a high sensitivity of 177 pAμm−2μM−1 in response to the DA. It is concluded that the MPC aptamer/SiNW-FET sensor has shown improved specificity and an LOD up to <10−11 M for exocytotic DA detection, as compared to other existing electrochemical sensors. The real-time monitoring of DA induced by hypoxia demonstrates that for triggering the DA secretion, intracellular Ca2+ is required, which is commanded by extracellular Ca2+ influx instead of the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Such a device, capable of coalescing with living cell systems, opens a new gateway towards the biosensor for the futuristic studies of clinical disease diagnostics.

Figure 1. (a) DNA-aptamer-modified MPC SiNW-FET biosensor for dopamine; illustration of FET device for detecting exocytotic dopamine under hypoxic stimulation from living PC12 cells; (b) a semi-log plot of response as a function of dopamine concentration [10]. (c) Schematics of a graphene-based electrode used for measurements of DA; graphene electrode is mounted on a SiO2/Si substrate, and a fluidic chamber is filled with PBS solution containing target dopamine; (d) SEM image of the graphene-based sensor array; AFM topographic image of CVD grown multilayer graphene (e) mechanism behind the FSCV measurements of dopamine; and (f) noticeable area-normalized electrochemical current (IEC) response to the dopamine concentrations [11].

2. Analytical Performances of DA Graphene-Based Biosensors

Detecting biomolecules in real samples is associated with the interaction of other compounds with similar oxidation potentials during detection [12]. Thus, designing sensors for the DA monitoring in biological samples, such as routine clinical ones, is challenging since electrochemically active compounds commonly found in body fluids, such as AA, uric acid (UA), and glucose (Glu), constantly interact with each other during detection due to their similar oxidation potentials. Moreover, the present macromolecules, including proteins, can non-specifically adsorb on the electrode surface, thus hindering the electron transfer rate [13]. Thus, the development of electrochemical methods for the analysis of DA in a complex matrix must address all these possible interactions to enable its successful DA detection in a simple, rapid, and highly selective way.

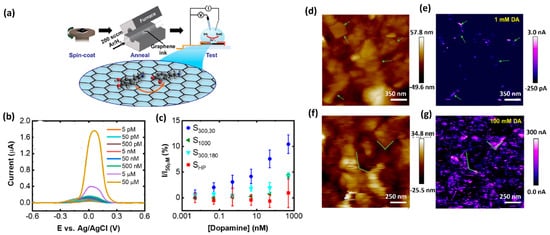

The limitation caused by overlapping voltametric signals of compounds with very close oxidation potentials and relatively poor selectivity can be avoided by applying different sensing layers that enable separate detection of the electrochemical signals. Several electrode-modification substances, such as oxides, conducting polymers, and nanomaterial, have been adopted for this purpose. Nanomaterial-modified electrodes, especially with graphene and its derivatives, such as reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and graphene oxide (GO), have recently attracted great focus in electrochemical biosensing approaches [14][12][15][16][17][18][19]. Due to their unique structure, graphene-based materials increase the conductivity of the compounds used in electrochemical measurement systems. Owing to their large surface area, they offer a high number of accessible active sites to detect analytes (Figure 2) [17]. Graphene is always admired for its excellent properties among the various sensing materials for DA due to its excellent electrical conductivity and π−π interaction between the aromatic rings of DA and graphene. Butler et al. developed a graphene ink-based, ultrasensitive electrochemical sensor for the detection of DA. The lowest limit of detection is reported as 1 nM. This sensitivity and selectivity of the sensor are achieved by tuning the surface chemistry of graphene. Figure 2a shows a schematic illustration of the fabrication of the DA sensor. The curves of Figure 2b depict the effect of annealing the graphene towards the DA response from 55 pM to 50 μM, using DPV measurements. Scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) mapping confirmed that the graphene layer (Figure 2d−g) shows higher oxidation at the edges of the flakes. Figure 2d,f display the height maps for two different regions of the graphene ink film-based sensor. Figure 2, for example, shows the electrochemical mapping of the graphene ink with 100 mM DA in PBS. At different concentrations, the total activity is enhanced, as seen by the increased magnitude of the current in the electrochemical response. Considering the 2D defects and the active edge sites of graphene ink, it can be an ideal candidate for printable and low-cost DA sensing devices/systems.

Figure 2. (a) Schematic representation of fabrication and electrochemical testing process of the graphene ink-based DA sensor. (b) Differential pulse voltammogram of the response towards DA detection from 5 pM to 50 μM. (c) Normalized peak current values versus DA concentration. (d) Height map, measured using scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) and (e) the corresponding electrochemical map with 1 mMDA. (f) A height map of a different region of the graphene film and (g) the corresponding electrochemical map with 100 mM DA [15].

Butler et al. developed ultrasensitive graphene ink which enabled facile post-deposition annealing of electrochemical sensor for DA detection with the lowest detection limit of 1 nM [13][15]. Furthermore, by increasing the affinity of the cationic DA form to the materials’ surface, electroactive oxygen groups in graphene materials play a significant role in its detection [20]. Graphene can also be easily modified with various nanomaterials to attain an enhanced catalytic effect [13]. However, the abovementioned advantages of graphene are limited due to the strong π–π stacking and van der Waals interactions. Therefore, surface modifications of the graphene nanosheets, made to improve its functionalization, must, to be effective, reduce these unfavorable effects while also providing enhancement of the electrocatalysis of graphene, increasing the surface area, and improving the conductivity of the composite materials. Moreover, the biofunctionalization aims not only to improve the analytical performance characteristics, such as sensitivity and selectivity, but also to enable miniaturization of the diagnostic platform to make it convenient for the analysis of real and complex matrices, and to make it able to perform monitoring in real time, as well as in in vivo testing [13].

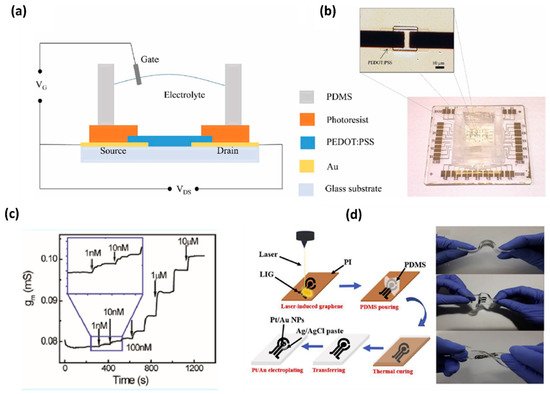

Wang et al. developed organic electrochemical transistors (OECT) for accurate sensing of DA based on the alternative current (AC) measurements [19], as shown in Figure 3. This advanced method was introduced to characterize the behavior of ionic motion and the ion concentrations in aqueous electrolytes, as well as the rapid electrochemical detection of DA with an LOD of 1 nM. This AC method gives a stable and accurate signal in a broad frequency range and a low noise level by introducing a lock-in amplifier. Therefore, the AC method opened a new window for OECT-based sensors [21]. Xue-Xui et al. developed a high-flexibility and high-selectivity DA sensor with a simple fabrication process. Thus, the fabricated Pt–Au/LIG/PDMS sensor exhibited a sensitivity of 865.8μA/mM cm−2 and a limit of detection of 75 nM, and successfully detected DA in human urine. The flexibility of the sensor offers the possibility for continuous DA monitoring in future self-care monitoring systems [22].

Figure 3. (a) Schematic diagram of an OECT device for DA sensing. (b) Optical image of the transistor and the whole OECT array. (c) Channel transconductance (gm) response to additions of DA with different concentrations [21]. (d) Fabrication of flexible electrochemical DA sensor with a Pt-AuNPs/LIG/PDMS electrode and display of flexibility of the fabricated electrode [22].

Along with the electrochemical biosensors, fluorescence biosensors are attractive due to their high sensitivity and rapid response. In terms of signal transduction, fluorescence biosensors are categorized as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [23], chemiluminescence [24], fluorescence dye staining [25], fluorescent probe [26], and fluorescence anisotropy [27] biosensors, and have been proven to be promising devices for diagnostics. The GO derivatives of graphene have the ability to quench the fluorescence of the adsorbed dyes due to their conjugated structure. A. Teniou et al. developed GO-based fluorescent aptasensor for DA detection [23]. In this sensor, there is a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) device where GO plays the role of an energy donor and a carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled aptamer is the energy acceptor. The thus-developed GO-based aptasensor depicts a linear relationship between DA concentration (3 to 1680 nm) and fluorescence recovery. The calculated value of the LOD is 0.031 nM. R.

3. Challenges and Perspectives towards POC Diagnostics of DA

The detection of DA has been of great interest for clinical implications because the neurotransmitter can be used as a biomarker for PD diagnosis, and which can help with monitoring the disease progression and its treatment effectiveness [28]. In fact, as the disease progresses and side effects appear, individualization of therapy is recommended. Because of the nonlinearities of levodopa, DA, and basal ganglia dynamics, which account for PD progression, there is an unmet need to estimate individuals’ parameters, including DA level, for DRT dosing adaptation. So far, algorithms have been developed to tailor DRT based on information acquired by wearable sensors which estimate the physiological and pharmacokinetic parameters [29][30]. Simultaneous monitoring of DA levels could improve individualized drug regimen optimization and help predict sudden waning in levodopa’s effect. The development of in vivo sensing devices is currently in its beginning; the currently available electrochemical devices dedicated to DA detection are too large for on-field inspection [13].

Fulfilling this goal is associated with moving away from time- and cost-consuming laboratory analysis that requires skilled technicians to point of care testing (POCT), i.e., medical tests performed close to the site of patient care. The POC devices face significant challenges for achieving reliable results quickly (a few minutes) without sample pretreatment. They should be portable and user-friendly while providing acceptable analytical performance and clinical significance. Electrochemical sensors meet the main requirements of POCT, such as sensitivity, selectivity, ease of handling, affordability, disposability, stability, and flexibility. Electrochemical biosensors, which can be miniaturized, facilitate work with real samples in small volumes (μL-nL) without any pretreatment and versatility due to multiple sensor arrays, and show advantages compared to optical biosensors when used in POC devices [31].

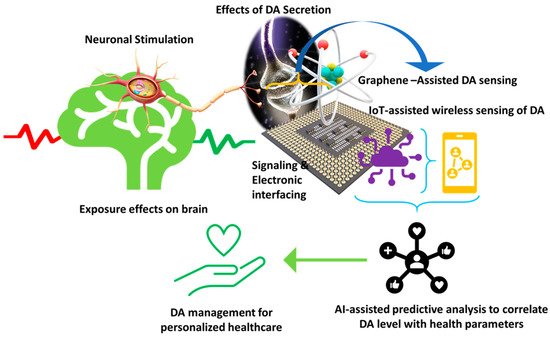

Considering the acceptable selectivity and sensitivity of the graphene-modified electrochemical biosensors for DA, and the simplicity of the measurement process, they can potentially be applied to POC testing [32]. Hence, developing a portable and miniaturized sensing platform for DA detection is significant for this approach. Moreover, since electrochemical biosensors can be easily combined with digital signal readout, smartphone-based integrated systems for simultaneous detection of biomolecules, including DA, have been developed (Figure 4). They allow real onsite measurement of DA, which can immediately be shared with the clinician [31]. The systems usually consist of a disposable sensor with a graphene-modified electrode, a coin-size detector, and a smartphone equipped with application software.

Figure 4. Illustration of a futuristic approach based on sensor-IoT-AI-goal of PD management.

Another area of research that still requires increased attention is the development method for noninvasive DA detection with acceptable reproducibility and stability in clinical diagnostics. In this sense, the measurement of salivary DA without pretreatment or modification of the samples, and with satisfactory results that are comparable to the clinical test, is highly desirable.

The POCT approach appears to be a promising step toward optimizing DRT and clinical trial designing as well; however, it requires translation of the findings into a mobile health decision tool. As Lingervelder et al. have reviewed, for general practitioners, the clinical utility of POC testing is the most critical aspect [26]. To ensure POCT’s usefulness to clinicians, future research [33], despite focusing on the analytical and technical performances of a test, should also tackle the aspects relating to the clinical utility and risks [34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42].

References

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912.

- Cheng, H.C.; Ulane, C.M.; Burke, R.E. Clinical progression in Parkinson disease and the neurobiology of axons. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 67, 715–725.

- Eldrup, E.; Mogensen, P.; Jacobsen, J.; Pakkenberg, H.; Christensen, N.J. CSF and plasma concentrations of free norepinephrine, dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), and epinephrine in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1995, 92, 116–121.

- Goldstein, D.S.; Sullivan, P.; Holmes, C.; Kopin, I.J.; Basile, M.J.; Mash, D.C. Catechols in post-mortem brain of patients with Parkinson disease. Eur J. Neurol 2011, 18, 703–710.

- Asif, M.; Liu, H.; Aziz, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Ajmal, M.; Xiao, F.; Liu, H. Core-shell iron oxide-layered double hydroxide: High electrochemical sensing performance of H2O2 biomarker in live cancer cells with plasma therapeutics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 97, 352–359.

- Asif, M.; Aziz, A.; Ashraf, G.; Iftikhar, T.; Sun, Y.; Xiao, F.; Liu, H. Unveiling microbiologically influenced corrosion engineering to transfigure damages into benefits: A textile sensor for H2O2 detection in clinical cancer tissues. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131398.

- Asif, M.; Haitao, W.; Shuang, D.; Aziz, A.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, F.; Liu, H. Metal oxide intercalated layered double hydroxide nanosphere: With enhanced electrocatalyic activity towards H2O2 for biological applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 239, 243–252.

- Atcherley, C.W.; Laude, N.D.; Monroe, E.B.; Wood, K.M.; Hashemi, P.; Heien, M.L. Improved Calibration of voltammetric sensors for studying pharmacological effects on dopamine transporter kinetics in vivo. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 1509–1516.

- Asif, M.; Aziz, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Ajmal, M.; Xiao, F.; Chen, X.; Liu, H. Superlattice stacking by hybridizing layered double hydroxide nanosheets with layers of reduced graphene oxide for electrochemical simultaneous determination of dopamine, uric acid and ascorbic acid. Mikrochim. Acta 2019, 186, 61.

- Li, B.R.; Hsieh, Y.J.; Chen, Y.X.; Chung, Y.T.; Pan, C.Y.; Chen, Y.T. An ultrasensitive nanowire-transistor biosensor for detecting dopamine release from living PC12 cells under hypoxic stimulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16034–16037.

- Wu, T.; Alharbi, A.; Kiani, R.; Shahrjerdi, D. Quantitative principles for precise engineering of sensitivity in graphene electrochemical sensors. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1805752.

- Ji, D.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Low, S.S.; Lu, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhu, L.; Li, C.; Liu, Q. Smartphone-based integrated voltammetry system for simultaneous detection of ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid with graphene and gold nanoparticles modified screen-printed electrodes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 119, 55–62.

- Cernat, A.; Ştefan, G.; Tertis, M.; Cristea, C.; Simon, I. An overview of the detection of serotonin and dopamine with graphene-based sensors. Bioelectrochemistry 2020, 136, 107620.

- Si, Y.; Park, Y.E.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, H.J. Nanocomposites of poly(l-methionine), carbon nanotube-graphene complexes and Au nanoparticles on screen printed carbon electrodes for electrochemical analyses of dopamine and uric acid in human urine solutions. Analyst 2020, 145, 3656–3665.

- Butler, D.; Moore, D.; Glavin, N.R.; Robinson, J.A.; Ebrahimi, A. Facile Post-deposition Annealing of Graphene Ink Enables Ultrasensitive Electrochemical Detection of Dopamine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 11185–11194.

- Bhardwaj, S.K.; Chauhan, R.; Yadav, P.; Ghosh, S.; Mahapatro, A.K.; Singh, J.; Basu, T. Bi-enzyme functionalized electrochemically reduced transparent graphene oxide platform for triglyceride detection. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 1598–1606.

- Sheetal, K.B.; Basu, T. Study on binding phenomenon of lipase enzyme with tributyrin on the surface of graphene oxide array using surface plasmon resonance. Thin Solid Films 2018, 645, 10–18.

- Bhardwaj, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Ghosh, S.; Basu, T.; Mahapatro, A.K. Biosensing Test-Bed Using Electrochemically Deposited Reduced Graphene Oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 24350–24360.

- Bhardwaj, S.K.; Basu, T.; Mahapatro, A.K. Triglyceride detection using reduced graphene oxide on ITO surface. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2017, 184, 92–98.

- Minta, D.; Moyseowicz, A.; Gryglewicz, S.; Gryglewicz, G. A Promising Electrochemical Platform for Dopamine and Uric Acid Detection Based on a Polyaniline/Iron Oxide-Tin Oxide/Reduced Graphene Oxide Ternary Composite. Molecules 2020, 25, 5869.

- Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yan, F. AC Measurements Using Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Accurate Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 25834–25840.

- Hui, X.; Xuan, X.; Kim, J.; Park, J.Y. A highly flexible and selective dopamine sensor based on Pt-Au nanoparticle-modified laser-induced graphene. Electrochimica Acta 2019, 328, 135066.

- Ahlem, T.; Amina, R.; Gaëlle, C. A Simple Fluorescent Aptasensing Platform Based on Graphene Oxide for Dopamine Determination. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021.

- Cheng, R.; Ge, C.; Qi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, J.; Huang, H.; Pan, T.; Dai, Q.; Dai, L. Label-Free Graphene Oxide Förster Resonance Energy Transfer Sensors for Selective Detection of Dopamine in Human Serums and Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 13314–13321.

- Wang, Y.; Kang, K.; Wang, S.; Kang, W.; Cheng, C.; Niu, L.M.; Guo, Z. A novel label-free fluorescence aptasensor for dopamine detection based on an Exonuclease III- and SYBR Green I- aided amplification strategy. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 305, 127348.

- Suzuki, Y. Development of Magnetic Nanobeads Modified by Artificial Fluorescent Peptides for the Highly Sensitive and Selective Analysis of Oxytocin. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20, 5956.

- Walsh, R.; DeRosa, M.C. Retention of function in the DNA homolog of the RNA dopamine aptamer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 388, 732–735.

- Steckl, A.J.; Ray, P. Stress Biomarkers in Biological Fluids and Their Point-of-Use Detection. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 2025–2044.

- Véronneau-Veilleux, F.; Ursino, M.; Robaey, P.; Lévesque, D.; Nekka, F. Nonlinear pharmacodynamics of levodopa through Parkinson’s disease progression. Chaos 2020, 30, 093146.

- Thomas, I.; Alam, M.; Bergquist, F.; Johansson, D.; Memedi, M.; Nyholm, D.; Westin, J. Sensor-based algorithmic dosing suggestions for oral administration of levodopa/carbidopa microtablets for Parkinson’s disease: A first experience. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 651–658.

- Campuzano, S.; Pedrero, M.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. New challenges in point of care electrochemical detection of clinical biomarkers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 345, 130349.

- Shen, X.; Ju, F.; Li, G.; Ma, L. Smartphone-Based Electrochemical Potentiostat Detection System Using PEDOT: PSS/Chitosan/Graphene Modified Screen-Printed Electrodes for Dopamine Detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 2781.

- Lingervelder, D.; Koffijberg, H.; Kusters, R.; IJzerman, M.J. Point-of-care testing in primary care: A systematic review on implementation aspects addressed in test evaluations. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 73, e13392.

- Nehra, M.; Uthappa, U.T.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Dixit, C.; Dilbaghi, N.; Mishra, Y.K.; Kumar, S.; Kaushik, A. Nanobiotechnology-assisted therapies to manage brain cancer in personalized manner. J. Control. Release 2021, 338, 224–243.

- Khunger, A.; Kaur, N.; Mishra, Y.K.; Chaudhary, G.R.; Kaushik, A. Perspective and prospects of 2D MXenes for smart biosensing. Mater. Lett. 2021, 304, 130656.

- Fuletra, I.; Chansi; Nisar, S.; Bharadwaj, R.; Saluja, P.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Asokan, K.; Basu, T. Self-assembled gold nano islands for precise electrochemical sensing of trace level of arsenic in water. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 12, 100528.

- Pal, K.; Asthana, N.; A Aljabali, A.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Kralj, S.; Penkova, A.; Thomas, S.; Zaheer, T.; de Souza, F.G. A critical review on multifunctional smart materials ‘nanographene’ emerging avenue: Nano-imaging and biosensor applications. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2021, 1–17.

- Sharma, P.K.; Kim, E.-S.; Mishra, S.; Ganbold, E.; Seong, R.-S.; Kaushik, A.K.; Kim, N.-Y. Ultrasensitive and Reusable Graphene Oxide-Modified Double-Interdigitated Capacitive (DIDC) Sensing Chip for Detecting SARS-CoV-2. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 3468–3476.

- Ortiz-Casas, B.; Galdámez-Martínez, A.; Gutiérrez-Flores, J.; Baca Ibañez, A.; Kumar Panda, P.; Santana, G.; de la Vega, H.A.; Suar, M.; Gutiérrez Rodelo, C.; Kaushik, A.; et al. Bio-Acceptable 0D and 1D ZnO nanostructures for cancer diagnostics and treatment. Mater. Today 2021.

- Kaushik, A.; Khan, R.; Solanki, P.; Gandhi., S.; Gohel, H.; Mishra, Y.K. From Nanosystems to a Biosensing Prototype for an Efficient Diagnostic: A Special Issue in Honor of Professor Bansi, D. Malhotra. Biosensors 2021, 11, 359.

- Sharma, K.P.; Ruotolo, A.; Khan, R.; Mishra, Y.K.Y.; Kaushik, N.K.; Kim, N.-Y.; Kaushik, A.K. Perspectives on 2D-borophene flatland for smart bio-sensing. Mater. Lett. 2021, 308, 31089.

- Bhardwaj, S.K.; Mujawar, M.; Mishra, Y.K.; Hickman, N.; Chavali, M.; Kaushik, A. Bio-inspired graphene-based nano-systems for biomedical applications. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 502001.

More

Information

Subjects:

Engineering, Biomedical

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.0K

Entry Collection:

Neurodegeneration

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

04 Nov 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No