Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stephen Pruett-Jones | + 3135 word(s) | 3135 | 2021-08-30 08:20:13 |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Pruett-Jones, S. Naturalized Parrots. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15241 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Pruett-Jones S. Naturalized Parrots. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15241. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Pruett-Jones, Stephen. "Naturalized Parrots" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15241 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Pruett-Jones, S. (2021, October 21). Naturalized Parrots. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15241

Pruett-Jones, Stephen. "Naturalized Parrots." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 October, 2021.

Copy Citation

Parrots have been transported and traded by humans for at least the last 2000 years and this trade continues unabated today. This transport of species has involved the majority of recognized parrot species (300+ of 382 species). Inevitably, some alien species either escape captivity or are released and may establish breeding populations in the novel area. With respect to parrots, established but alien populations are becoming common in many parts of the world.

naturalized parrots

introduced species

invasive species

world parrot trade

invasion biology

1. Introduction

Parrots have been transported and traded by humans for at least the last 2000 years and this trade continues today [1]. Cardador et al. [2] summarized trade data available through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES [3]) and documented that during the 20-year period 1975 to 2015, more than 19 million individual parrots of 336 species were legally traded among countries. This involved an average of more than half a million birds each year, with the parrot trade representing approximately 25% of all legal bird trade [2].

Inevitably, some individuals of introduced alien species either escape captivity and/or are accidentally or purposefully released and may begin breeding in the wild in the novel area [4][5]. Parrots are no exception and released or escaped parrots are often quite successful at surviving in the wild in new areas. Over time, if a successful breeding population is established, the species would be considered naturalized in that area. In some cases, the new populations can expand rapidly and grow exponentially in size [6][7][8][9][10]. If the species extends its naturalized range and establishes additional populations, it may become invasive.

Naturalized and invasive species are increasing worldwide, and parrots represent an increasingly large proportion of the naturalized bird species [11][12]. Although the invasive nature of established foreign parrot species is debated [13][14][15], naturalized parrot populations are increasing in distribution and size. Additionally, their interactions with humans are also increasing and becoming more complex and involve both positive and negative aspects [16][17][18][19][20]. This interaction with humans also includes control of some populations. In many cities around the world two common introduced parrots, the Rose-ringed Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) and Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) are being controlled due to real or perceived problems with human activity. This is also true for some species in their native distribution [21].

The wildlife trade that ultimately gives rise to naturalized populations of parrots can also directly and negatively impact populations of species in their native ranges [22]. In many cases, this trade is causing species to be endangered in their native area, while at the same time inadvertently creating the possible situation where a population may establish itself in a novel and foreign area. In addition, the established populations can have impacts on local and native species [13]. It seems critical, therefore, to know exactly how many parrot species have established breeding populations in novel areas outside of their natural distribution. Such information is critical for monitoring introduced populations, informing management priorities, and understanding how introduced population may relate to the conservation of endangered populations in the native range of species [20]. That is the purpose of this review. We summarize multiple databases and attempt to arrive at an estimate for the number of parrot species both introduced and naturalized in the world. Our effort includes providing a database combining information from separate sources for use by other researchers.

Efforts to estimate the number of naturalized parrots have been made for almost two decades, and a comparison of the results highlights that the number and distribution of naturalized parrots is increasing. In one of the first efforts at counting naturalized parrots, Lever [23]; see also [24] reported that 34 species of parrots established naturalized populations. Two years later, Runde et al. [25] reported that there were 39 naturalized parrot species. Subsequently, Menchetti and Mori [13] reported about 60 parrot species were breeding outside their native distribution, and Avery and Shiels [26] reported 54 species have been introduced into foreign areas and 38 of these have become established. Most recently, Royle and Donner [24] examined records in the Global Avian Invasion Atlas (GAVIA) database [27] from 1993–2012 and documented records of 129 species of parrots observed in 106 countries. From these records, Royle and Donner concluded that there were at least 47 species of parrots in 21 genera that are naturalized in at least one country outside their native range. Lastly, a recent estimate of the geographical range of naturalized parrots is that of Mori and Menchetti [15] in which they conclude that species are found in 47 countries and all continents except Antarctica [28][29][30]. The variation in recent estimates is due in part to the sources of the information reviewed, and the time frame considered. Although our study is also subject to the same limitations, our review represents the first attempt to estimate the number of naturalized species based on a combination of the available data sets that have previously been analyzed separately. Additionally, for the United States, we compare the data from the public data sets with detailed reviews and field observations to examine the consistency and accuracy in the public data sets.

3. Current Researches and Results

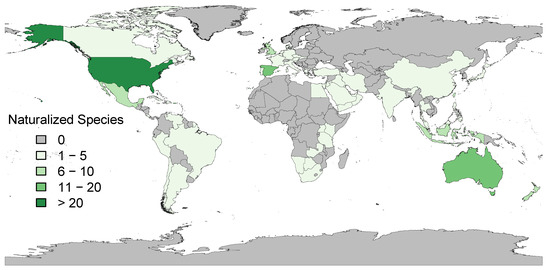

Based on the GAVIA, eBird, and iNaturalist databases (hereafter referred to as the combined database), there are records of 166 species of Psittaciformes having been introduced (seen in the wild) in 120 countries or territories outside of the native range (Figure 1; Tables S1 and S2). These species comprise 43% (166 of 382) of all known species of Psittaciformes and approximately half (49.4%, 166 of 336) of the species of parrots identified in the international parrot trade [2]. Of these 166 species, 60 species have been recorded or are now known to be naturalized and an additional 11 species are breeding in at least one country outside of their native range, being present in a total 86 countries or territories.

Figure 1. The distribution of naturalized and breeding species of parrots (Psittaciformes), according to the GAVIA (Dyer et al., 2017) dataset. The map depicts how many species of introduced Psittaciformes are naturalized or breeding per country. See text for definitions.

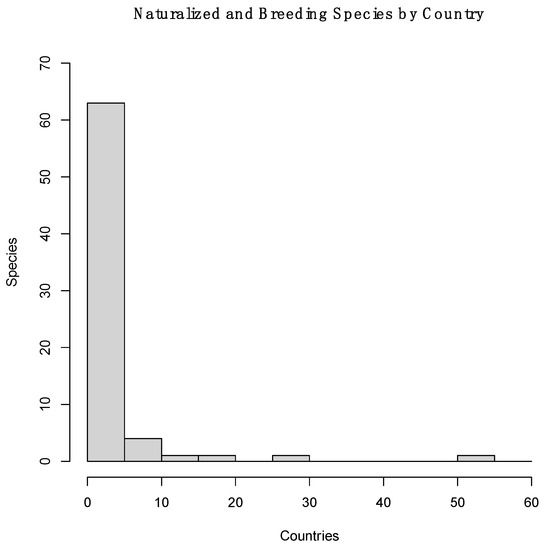

For the 71 species either breeding or naturalized, the mean number of countries (or territories) in which these species occur is 3.8 with a wide range of 1–51 (Figure 2). Almost half (30) of these species are recorded as either breeding or having a naturalized population in just one country. The six most widely distributed naturalized parrots, in terms of countries occupied are: Rose-ringed Parakeet, naturalized in 47 countries or territories; Monk Parakeet, naturalized in 26 countries or territories; Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus), naturalized in 12 countries or territories; Alexandrine Parakeet (Psittacula eupatria) naturalized in 12 countries or territories; Brown-throated Parakeet (Eupsittula pertinax), naturalized in eight countries or territories; and Grey-headed Lovebird (Agapornis canus), naturalized in six countries or territories (Table S1).

Figure 2. The frequency distribution of introduced and naturalized or breeding species of parrots (Psittaciformes) across countries.

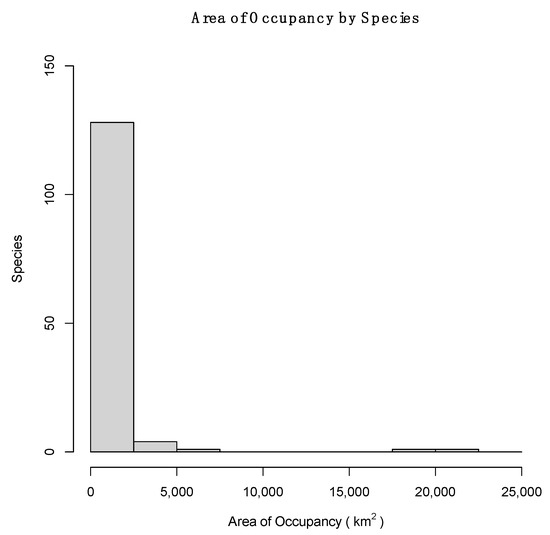

Countries vary enormously in size, and the area of occupancy (AOO) is a more objective measure of the geographical distribution of introduced populations than number of countries occupied. For introduced parrots (species observed in the wild outside their native range), the AOO varied widely. The mean AOO was 714.3 km2 (n = 135; range = 4–21,944 km2; SD = 2595.7; Figure 3). Above, the six most widely distributed parrots are listed in terms of countries occupied. This list changes when considering AOO. The six species with the largest AOO of introduced populations are: Monk Parakeet (21,944 km2), Rose-ringed Parakeet (18,812 km2), Eastern Rosella (Platycercus eximus, 5976 km2), Nanday Parakeet (Aratinga nenday, 4840 km2), Red-crowned Amazon (Amazona viridigenalis, 3376 km2) and Budgerigar (3172 km2). Only the Monk Parakeet and Rose-ringed Parakeets overlap in these two ranked lists. Figures S1–S6 illustrate the global distributions of the sightings of these six species outside their native ranges.

Figure 3. The frequency distribution of introduced and naturalized or breeding species of parrots (Psittaciformes) by their AOO (Area of Occupancy). The AOO only refers to introduced populations.

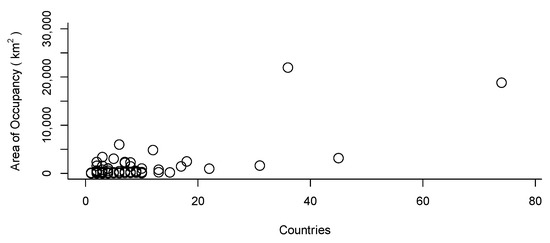

Despite the difference between countries as an indicator of geographical spread and AOO, there was a significant correlation between the number of countries a species was introduced in and the AOO (Figure 4; Spearman Rs = 0.732, p < 0.001).

Figure 4. Relationship between area of occupancy and the number of countries that introduced parrots have been seen in the wild or are naturalized or breeding.

In terms of countries supporting naturalized parrots, and based on the combined database, the six countries or territories with the largest number of naturalized or breeding species are: United States (40 species), Australia, Spain, and Puerto Rico each with 14 species, Taiwan (9 species), and Singapore (8 species). This order is different if we consider records for all introduced species combined. That list is: United States (87 species), Brazil and Spain with 52 species, Australia and Puerto Rico with 35 species, and Mexico (20 species) (Table S1).

The records for Australia of 13 naturalized species (Table S1) illustrate the complexity of the parrot trade and the current distribution of introduced species. Currently in Australia, there is only one introduced species likely to be naturalized at present, the Rose-ringed Parakeet [31]. The other naturalized species in Australia isted in Table S1 are native to Australia but introduced in areas outside of their native range on the continent [31]. Thus, these species fall within the definition of transported, introduced, and naturalized used by authors, but the species’ novel distributions are still within their native country Australia.

For the continental United States, there are records of 85 species of parrots introduced, breeding, or naturalized (Tables S1 and S2). At least two of these records are suspected to be in error or are inaccurate (that of Kuhl’s Lorikeet Vini kuhlii and Kakapo Strigops habroptila), leaving 83 species. In comparison, the work by Uehling et al. [32][33], focusing on the continental United States during the 15-year period from 2002–2016, documented records of 56 species of parrots either introduced or naturalized. These two lists (the combined database (Table S1) and Uehling et al. [33][34]) overlap considerably when only considering naturalized species, but less so when considering all species. Thus, of the 25 naturalized species listed in [33], all but three are listed as naturalized or breeding in the combined database. Similarly, of the 22 species listed as naturalized in the combined database, 16 species are also listed as naturalized by Uehling et al. [33]. There is even greater overlap for the data in Hawaii and Puerto Rico. Of the five species of parrots listed by VanderWerf and Kalodimos [35] as naturalized in Hawaii, each of those species is listed as naturalized in the combined database (Table S3). For Puerto Rico, of the 12 naturalized species identified by Falcón and Tremblay [32], all of these species are listed as either introduced, breeding, or naturalized in the combined database (Table S3). Despite this considerable overlap when considering currently known naturalized species, the combined database (Table S1) also contains records of many species that have not been recently confirmed or verified. Thus, for the continental US, the combined database contains records of 28 introduced and eight breeding or naturalized species not confirmed by Uehling et al. [33][34].

Combining the lists of the recent studies [32][33][34][35], 28 species of Psittaciformes are naturalized in either the continental US, Hawaii, or Puerto Rico, and an additional 15 species are breeding there (43 species total). If we ask the same question of the combined database, there are records of 26 species as naturalized in either the continental US, Hawaii, or Puerto Rico, and an additional 14 species are breeding there (40 species total).

3. Discussion

Parrots are one of the most endangered groups of birds in the world, and in part this is because of the global trade driven primarily by the pet trade. As a result of this international trade, parrots as introduced and naturalized species are also among the most widely distributed groups of birds in the world, although much of this distribution is in novel areas outside of species’ native ranges. It was our goal in this review to attempt to estimate the number of naturalized species of parrots in the world. This effort updates past estimates [13][23][25][26] and provides a combined database of parrot specific records from GAVIA, eBird, and iNaturalist available for use by other researchers. While previous efforts have utilized separate data sets, by combining data sets our goal was to a reliable, current estimate for introduced parrots around the world.

Of the 382 extant species of Psittaciformes, the majority of these (336) have been transported around the world through the global pet trade [2]. Our review indicates that almost half of these species (49.4%, 166 of 336) have escaped captivity or been released in novel areas and observed in the wild in no less than 120 countries or territories. Not surprisingly, introduction in a new area does not guarantee establishment success, but nevertheless at least 71 species are known to have established breeding or naturalized populations in 86 different countries or territories. Considering past estimates of the number of naturalized species [13][23][25][26] it is obvious that the number of naturalized parrots has increased over time. Part of this increase is related to a general increase in parrot trade around the globe [2], although this trade has changed drastically in some areas due to bans on trade that been imposed by the governments in some areas, e.g., the United States and the European Union (2,4,11,45). Some of the increase in naturalized parrots is likely also related to increased numbers of escapes or releases of individuals already present in a locality as the result of past trade activity.

There are necessary qualifications to the data that we summarized as well as our methods of analysis. Citizen science data are increasingly used to examine distributional patterns of species worldwide including introduced parrots [24][32][36][37][38]. Nevertheless, issues concerning species identification and spatial and temporal biases in sampling must be considered in analysis and interpretation [37][38][39][40]. Our combined database (Table S1) is subject to these considerations, and our conclusions about the numbers of introduced and naturalized species should be viewed as our best attempt to conservatively review the data available in public databases.

The GAVIA database is an important resource as a starting point, but given that it is not being updated with respect to changes in taxonomy and current research on the distribution and status of individual species, the importance of this database will likely decrease over time. It is also the case for many species, the status as based on publications listed in the GAVIA database needs confirmation from more recent sources. Similarly, our use of a 250 km distance as a filter for observations from eBird affects our conclusion about the number of introduced species. Without such a filter, every extralimital observation of a species would have been included but, in our opinion, would not have improved our understanding of the number or distribution of naturalized parrots. If a transported species establishes a new population on a new island or in a far-distant country, it is clearly a novel naturalized population. However, if an extralimital population establishes itself close to the native population, it is simply a matter of judgement or semantics whether that population is considered naturalized or just an example of a range expansion. This is particularly true in some countries, e.g., Australia, where the majority of naturalized parrot species are also species native to Australia. It is also the case that for some poorly studied species, the actual native distribution may not be fully known. In these cases, observations listed in eBird and iNaturalized that meet our distance criteria of 250 km may, in fact, simply be observations of birds in the native range but misclassified as representing introduced populations.

For any geographical area, combining citizen science records with detailed field observations by knowledgeable researchers will ultimately yield the most accurate and reliable records for distribution of introduced parrots, as exemplified by [35]. We hope that by providing the combined database (Table S1) other researchers can use these data as the starting point for such field observations. Our comparison of the combined database with recent publications on parrots in the United States illustrates one method of checking for consistency and accuracy. This comparison showed general but not exact agreement for species either breeding or naturalized, but less so for all introduced species. Considerable overlap was expected given that both Uehling et al. [33] and this study made use of eBird data. However, Uehling et al. [33] reported species for which there was at least one observation recorded in eBird, whereas we used a minimum of three observations. Clearly, any conclusion we or other researchers reach is dependent on the exact data set examined. Although not summarized specifically here, comparison of the combined database with recent surveys of introduced parrots in England [41], Europe [42], Spain and Portugal [43], and South Africa [44] also show general agreement with respect to naturalized and breeding species.

Calculation of the area of occupancy (AOO) for introduced species allows for a more objective analysis of a species’ spread than just comparing the number of countries a species is recorded in. The number of countries a species has colonized as a naturalized species is important, but we expect that any examination of life-history correlates of success would be more likely to identify significant factors if such analyses focused on AOO. A comparison of the data for the two most common introduced species, the Rose-ringed Parakeet and Monk Parakeet, highlight the value of examining both measures of success. The Rose-ringed Parakeet is now naturalized in 47 countries, whereas naturalized Monk Parakeets are found in 26 countries. In contrast, the AOO of Monk Parakeets is ~15% larger than that of Rose-ringed Parakeets (21,944 km2 compared to 18,812 km2; Table S1). One possible explanation for this difference is that the Rose-ringed Parakeet is more widely traded worldwide in the pet trade than is the Monk Parakeet, leading to Rose-rings establishing themselves in more countries. In contrast, Monk Parakeets are highly adaptable and successful in areas where they establish themselves [45], leading to population increases and range expansions that would be observed through calculation of the AOO. We encourage consideration of both the AOO and countries occupied in future studies of the spread and success of introduced parrots.

Naturalized parrots are increasingly common in some areas and can present a host of both positive and negative interactions with humans. As Kiacz and Brightsmith [20] review, naturalized parrots offer timely and significant opportunities for conservation, research, and human society. The potential negative impacts of naturalized parrots, thoroughly reviewed by Mori and Menchetti [15] and Brightsmith and Kiacz [14] can be significant in some situations, as with damage to electrical infrastructure by Monk Parakeets or localized agriculture by some species. Nevertheless, overall, Brightsmith and Kiacz [14] conclude that these impacts are minor and do not in general justify the widespread and indiscriminate control of naturalized parrot species.

Given that populations of naturalized parrots are expanding, becoming urbanized in many cities, and generally representing larger fractions of local avifaunas, a greater understanding of their population biology, behavior, and interactions with humans is needed. We encourage regular local and regional surveys for species presence and abundance as well as large scale reviews of global patterns. Accurate data on the species richness and diversity of naturalized parrots will be critical for understanding the role of parrots as introduced and possibly invasive species, conservation efforts of threatened or endangered species, any management efforts when needed, and increasing the public knowledge and understanding of this important group of birds.

References

- Scheffers, B.R.; Oliveira, B.F.; Lamb, L.; Edwards, D.P. Global wildlife trade across the tree of life. Science 2019, 366, 71–76.

- Cardador, L.; Abellán, P.; Anadón, J.D.; Carrete, M.; Tella, J.L. The world parrot trade. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 13–21.

- CITES Trade Database. 2015. Available online: http://trade.cites.org/ (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Carrete, M.; Tella, J. Wild-bird trade and exotic invasions: A new link of conservation concern? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 6, 207–211.

- Vall-llosera, M.; Cassey, P. Leaky doors: Private captivity as a prominent source of bird introductions in Australia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172851.

- van Bael, S.; Pruett-Jones, S. Exponential population growth of monk parakeets in the United States. Wilson Bull. 1996, 108, 584–588.

- Hobson, E.A.; Smith-Vidaurre, G.; Salinas-Melgoza, A. History of nonnative Monk Parakeets in Mexico. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184771.

- Postigo, J.L.; Shwartz, A.; Strubbe, D.; Muñoz, A.R. Unrelenting spread of the alien monk parakeet in Israel. Is it time to sound the alarm? Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 349–353.

- Postigo, J.L.; Strubbe, D.; Mori, E.; Ancillotto, L.; Carneiro, I.; Latsoudis, P.; Menchetti, M.; Pârâu, L.G.; Parrott, D.; Rein, L.; et al. Mediterranean versus Atlantic monk parakeets Myiopsitta monachus: Towards differentiated management at the European scale. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 915–922.

- Jackson, H.A. Global invasion success of the rose-ringed parakeet. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 159–172.

- Cardador, L.; Lattuada, M.; Strubbe, D.; Tella, J.L.; Reino, L.; Figueira, R.; Carrete, M. Regional bans on wild-bird trade modify invasion risks at a global scale. Conservat. Lett. 2017, 10, 717–725.

- Aloysius, S.; Yong, D.; Lee, J.; Jain, A. Flying into extinction: Understanding the role of Singapore’s international parrot trade in growing domestic demand. Bird Conserv. Internat. 2020, 30, 139–155.

- Menchetti, M.; Mori, E. Worldwide impact of alien parrots (Aves Psittaciformes) on native biodiversity and environment: A review. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 26, 172–194.

- Brightsmith, D.J.; Kiacz, S. Are naturalized parrots priority invasive species? In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 133–155.

- Mori, E.; Menchetti, M. The ecological impact of introduced parrots. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 87–101.

- Senar, J.C.; Domènech, J.; Arroyo, L.; Torre, I.; Gordo, O. An evaluation of monk parakeet damage to crops in the metropolitan area of Barcelona. Anim. Biodiver. Conserv. 2016, 39, 141–145.

- Crowley, S.L. Human dimensions of naturalized parrots. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 41–53.

- Crowley, S.L.; Hinchliffe, S.; McDonald, R.A. Conflict in invasive species management. Front. Ecol. Environ 2017, 15, 133–141.

- Crowley, S.L.; Hinchliffe, S.; McDonald, R.A. The parakeet protectors: Understanding opposition to introduced species management. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 229, 120–132.

- Kiacz, S.; Brightsmith, D.J. Naturalized parrots: Conservation and Research Opportunites. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 71–86.

- Bucher, E.H. Management of human-parrot conflicts: The South American Experience. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 123–132.

- Tella, J.L.; Hiraldo, F. Illegal and legal parrot trade shows a long-term, cross-cultural preference for the most attractive species increasing their risk of extinction. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107546.

- Lever, C. Naturalised Birds of the World; A&C Black: London, UK, 2005.

- Royle, K.; Donner, W.B. The distribution of naturalized parrot populations. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 22–40.

- Runde, D.E.; Pitt, W.C.; Foster, J. Population ecology and some potential impacts of emerging populations of exotic parrots. In Managing Vertebrate Invasive Species: Proceedings of an International Symposium; Witmer, G.W., Pitt, W.C., Flagerstone, K.A., Eds.; USDA/APHIS Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Center: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2007; pp. 338–360.

- Avery, M.L.; Shiels, A.B. Monk and rose-ringed parakeets. In Ecology and Management of Terrestrial Vertebrate Invasive Species in the United States; Pitt, W.C., Beasley, J.C., Witmer, G.W., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 333–357.

- Dyer, E.E.; Redding, D.W.; Blackburn, T.M. The Global Avian Invasions Atlas: A database of alien bird distributions worldwide. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170041.

- Ancillotto, L.; Strubbe, D.; Menchetti, M.; Mori, E. An overlooked invader? Ecological niche, invasion success and range dynamics of the Alexandrine parakeet in the invaded range. Biol. Invas. 2015, 18, 583–595.

- Menchetti, M.; Mori, E.; Angelici, F.M. Effects of the recent world invasion by ring–necked parakeets Psittacula krameri. In Problematic Wildlife. A Cross-Disciplinary Approach; Angelici, F.M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 253–266.

- iNaturalist Alien Parrots Observatory. 2019. Available online: https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/alien-parrots-observatory?tab=species (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Rogers, A.M.; Kark, S. Australia’s urban cavity nesters and introduced parrots: Patterns, processes, and impact. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 277–292.

- Falcón, W.; Tremblay, R.L. From the cage to the wild: Introductions of Psittaciformes to Puerto Rico. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5669.

- Uehling, J.; Tallant, J.; Pruett-Jones, S. Status of naturalized parrots in the United States. J. Ornith. 2019, 160, 907–921.

- Uehling, J.; Tallant, J.; Pruett-Jones, S. Introduced and naturalized parrots in the Continental United States. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 193–210.

- VanderWerf, E.; Kalodimos, N.P. Statis of naturalized parrots in the Hawaiian Islands. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 211–226.

- Bonter, D.N.; Zuckerberg, B.Z.; Dickinson, J.L. Invasive birds in a novel landscape: Habitat associations and effects on established species. Ecography 2010, 33, 494–502.

- Dickinson, J.L.; Zuckerberg, B.; Bonter, D. Citizen science as an ecological research tool: Challenges and benefits. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2010, 41, 149–172.

- Minor, E.S.; Appelt, C.W.; Grabiner, S.; Ward, L.; Moreno, A.; Pruett-Jones, S. Distribution of exotic monk parakeets across an urban landscape. Urban Ecosys. 2012, 15, 979–991.

- Ratnieks, F.L.; Schrell, F.; Sheppard, R.C.; Brown, E.; Bristow, O.E.; Garbuzov, M. Data reliability in citizen science: Learning curve and the effects of training method, volunteer background and experience on identification accuracy of insects visiting ivy flowers. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1226–1235.

- Robinson, O.J.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.; Fink, D. Correcting for bias in distribution modelling for rare species using citizen science data. Diver. Distribut. 2018, 24, 460–472.

- Butler, C.J. Naturalized parrots in the United Kingdom. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 249–259.

- Braun, M.P. Introduced and naturalized parrots in Europe. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 227–239.

- Carrete, M.; Abellán, P.; Cardador, L.; Anadón, J.D.; Tella, J.L. The fate of multistage parrot invasions in Spain and Portugal. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 240–248.

- Symes, C.T.; Ivanova, I.M.; Howes, C.G.; Martin, R.O. Introduced and naturalized parrots of South Africa: Colonization and the wildlife trade. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 260–276.

- Calzada Preston, C.E.; Pruett-Jones, S.; Eberhard, J.R. Monk parakeets as a globally naturalized species. In Naturalized Parrots of the World: Distribution, Ecology, and Impacts of the World’s Most Colorful Colonizers; Pruett-Jones, S., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 173–192.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

905

Revision:

1 time

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Oct 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No