Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andrés J. Cortés | + 2065 word(s) | 2065 | 2021-09-27 08:38:30 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 2065 | 2021-10-09 04:10:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Cortés, A.J. Pre-Breeding for Biotic Resistance. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/14906 (accessed on 14 March 2026).

Cortés AJ. Pre-Breeding for Biotic Resistance. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/14906. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Cortés, Andrés J.. "Pre-Breeding for Biotic Resistance" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/14906 (accessed March 14, 2026).

Cortés, A.J. (2021, October 08). Pre-Breeding for Biotic Resistance. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/14906

Cortés, Andrés J.. "Pre-Breeding for Biotic Resistance." Encyclopedia. Web. 08 October, 2021.

Copy Citation

Genes and markers involved in resistance to biotic stress can be divided into two categories. The first is involved in pathogen recognition (e.g., RGA genes, resistance gene analogues), while the other is more involved in defense responses (e.g., DGA genes or defense gene analogues). The best-studied RGAs are leucine-rich repeats of nucleotide binding sites, kinase receptor-like proteins, pentatricopeptide repeats, and apoplastic peroxidases.

antagonistic biotic interactions

biotic stress

omnigenetics

pre-adaptation

genomics

1. Introduction

Forecasting tree responses to climate change has typically considered shifts in their phenology and geographic distribution in the face of changing abiotic pressures. However, biotic interactions may equally be altered by niche decoupling [1], in turn affecting tree populations’ adaptive and migration potentials [2]. Therefore, better and more integrative predictions require comprehensively assessing whether antagonistic and facilitated biotic interactions may be enhanced, maintained, or decoupled as a result of environmental fluctuations [3][4]. Otherwise, key forest services, both ecological (i.e., resources of biodiversity) and industrial (i.e., renewable materials such as wood, cellulose for the pulp industry, and lignin and hemicelluloses for energy production), may be jeopardized [5].

Fluctuating biotic interactions due to antagonistic biota such as pathogens, insect pests, and weeds are responsible for yield losses ranging from 17.2% up to 30.0% in major food crops [6]. Although studied to a lesser extent, the forestry sector presumably exhibits similar losses [7]. Despite the lack of explicit comprehensive assessments for forest trees, the effect of altered biotic stresses on forests must not be downplayed [8].

The pace at which climatic threats may be altering biotic interactions urges intensifying novel experimental and analytical approaches to better comprehend the effect on the plant disease triangle (PDT). PDT postulates that any plant disease is the result of the interaction between a host’s genotype, the biotic stress, and their environment [9]. Genomic prediction, machine learning, and gene editing strategies, although usually disentangled, offer powerful opportunities for trans-disciplinary and emergent inferences at the interface among the fields of forest genomics, pathology, and ecology [10].

Therefore, this review article aims to highlight major ecological evolutionary genomics’ tools to assist identification, conservation, and pre-breeding of biotic resistance in forest trees. Specifically, our first goal is to summarize the main trends when exploring the genomic basis (i.e., architecture) of biotic stress resistance in forest tree species, by wondering whether resistance types segregate as major Mendelian loci, a prediction from the Fisherian runaway [11] pathogen–host concerted arms-race [12] evolutionary model [13], or exhibit polygenic signatures across various phases of stress perception, signal amplification, and downstream responses. As a second goal, we aim to outline an integrative pipeline to detect and harness natural tree adaptation and pre-breeding for resistance to biotic stresses [14]. Powering integrative studies will enable a better understanding of climate change effects on forest trees’ responses to biotic stresses.

2. Novel Strategies to Speed up Tree Pre-Breeding for Biotic Stress Resistance

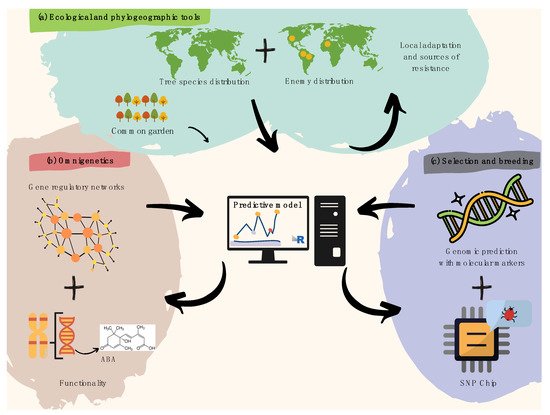

Tree pre-breeding requires an interdisciplinary approach [15] to speed up breeding cycles and increase selection accuracy in the face of jeopardizing climate change effects [16]. Such intersection (Figure 1) must happen among pathologists, botanists, ecologists, ecophysiologists, geneticists, biometeorologists, dendrologists, paleoecologists, and phylogeographers. DNA variation studies must not be disconnected from ecologically relevant trait variation in provenance trials, capable of revealing pre-adaptations to naturally high incidence of pathogenic fungi in humid niches, and insects that threaten the diversity of trees worldwide [17].

Figure 1. Recommendations for harnessing pre-breeding in forest tree pathology. (a) Spatial modeling of plant species and overlapping infectious agents is useful to identify resistance hotspots and pre-adaptations, later validated by common garden trials. (b) Gene regulatory networks (i.e., omnigenetics) enable to better explain the missing heritability in biotic resistance traits (diagram above within the pink bubble), while understanding trans-generational epigenetic inheritance as well as the metabolic bases for resistance (diagram below within the pink bubble). The diagram above functionality refers to a hypothetical example on metabolic pathways (e.g., biosynthesis of abscisic acid). (c) A last step aiming to search for molecular markers involved in attack and defense processes can further leverage pre-breeding for forest pathology via integrative predictive modeling of polygenic breeding values (diagram above within the purple bubble), which can easily be scalable using targeted genotyping SNP arrays/chips (diagram below within the purple bubble).

2.1. Leveraging Integrative Approaches

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in merging several disciplines to gather more cohesive inferences in the field of forest genetics [18]. For instance, molecular genetics has successfully coupled with the field of ecological biogeography and landscape ecology [19] to better understand the adaptive equilibrium between tree populations, and the niches where they occur [20]. This innovation has in turn informed potential long-term evolutionary responses [21].

The impact of pests and diseases on the distribution of forest trees, and their regeneration mechanisms [22], has been suggested as one of the main explanations for the high diversity of species in tropical forests [23]. Consequently, this hotspot is a valuable reservoir for sources of resistance. A better interaction between the fields of tree pre-breeding and phylogeography will allow a more comprehensive reconstruction of the ecological drivers, including antagonistic biotic interactions, of today’s diversity [7]. A first step in this regard requires mapping the geographical distributions of genealogical lineages across heterogeneous landscapes, for both pests and hosts (Figure 2a). The extent of overlap among trees and pathogens’ geographical distributions can then be used as a proxy to infer the likelihood for concerted evolution [24], and potential pre-adaptations [25]. Within this framework, evolutionary genetics may also offer promising avenues because it specifically deals with the mechanisms that explain the existence and maintenance of genetic variation across traits. While joint species distribution modeling prospectively informs the magnitude of biotic interactions at regional scales [23], multi-locality common garden (i.e., provenance trials), and clonal trials with trans-located biotic treatments, can in turn illuminate the other end of the spectrum [26]. Controlled reciprocal trials may offer a more mechanistic understanding of the ecological genomics of co-evolutionary interactions at local-scales [27].

2.2. Acknowledging and Harnessing Local Adaptation in Biotic Interactions

Local adaptation conceptualizes the trend that local populations tend to have a higher average fitness in their native environment than in other environments, or when compared with foreign introduced populations [28]. Despite this, local adaptation [29] has typically been over-simplified as driven by abiotic [30] heterogenetic interactions [31]. Until now, biotic interactions are starting to be recognized as major drivers, too [32]. Yet, one of the key challenges that remain in the study of local adaptation is to explore its genomic basis [23], either via loci exhibiting antagonistic pleiotropy or conditional neutrality [33]. These ecological and phylogeographic trends must be interpreted in the light of interacting gene networks (i.e., omnigenetics approach [34], Figure 1b).

Attempts to identify candidate genes of adaptive importance, and to relate genetic variation in these genes to phenotypic expressions in multi-locality field trials, have typically been hampered by a complex polygenic architecture [35], and a limited understanding of the physiological trade-offs [23]. For instance, theoretical expectations dictate that local selection at a single locus will promote local adaptation in the absence of gene flow (i.e., selection–migration balance [28]). However, more complex polygenic quantitative adaptation can even be established and maintained in the presence of high gene flow [36]. While the discipline of molecular quantitative tree genetics [37] merges with the field of ‘big data’ analytics [38], an expanded view of complex traits is arising, moving from a polygenic framework to a view in which all genes are liable to affect adaptation to biotic stresses (the omnigenic model described above, Figure 2b [34]), so that most heritability can be explained by the effects of rare variants, their second order epistatic interactions, and with epigenetic factors, even accounting in this way for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [39]. However, looking back, the metabolic basis of tree evolution still has the potential to improve plantations’ yields because natural selection has tested more options than humans ever will. Mining the molecular footprint of selection and adaptation from in situ sampling for tree pre-breeding and climate adaptation will benefit from bridging the gap between phenotyping and genotyping across provenances, and the more deterministic quantitative and population genetic models.

A useful type of polygenic model, yet to be calibrated within an omnigenic framework [34], is genomic prediction (GP) [40]. Predictive breeding via GP allows assessing genetic estimated values (GEVs) for biotic stress resistance [41]. GP uses historical resistance data to calibrate marker-based infinitesimal additive predictive models [42], which provide a more comprehensive representation of a quantitative polygenic trait than traditional genetic mapping [43], a tendency that several biotic resistances have started exhibiting [44]. Therefore, GP offers a key path to assist the introgression breeding of biotic stress resistance from key donors (via genomic-assisted recurrent backcrosses—GABC, as successfully applied in the breeding program for blight resistant in American chestnut trees [45]). GP’s predictive ability can be significantly enhanced after performing a priori weighted resistance mapping through more conventional methods such as quantitative-trait loci (QTL) mapping or genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [46]. These mapping strategies enable choosing target SNP arrays for high throughput genotyping of multi-parental populations [47] via SNP-Chips (Figure 1c).

GP may also go beyond pre-breeding efforts, and feedback on restoration optimization [48] and provenance characterization [49] (e.g., by predicting biotic resistance and yield) even across thousands of half-sib families that could hardly be tested at once in field and lab trials for pests and herbivore resistance [50]. Expectations within these half-sib families are likely similar to the ones previously discussed, which are as follows: (i) a nascent trend towards a more polygenetic architecture of the resistance, and (ii) the occurrence of pleiotropic genes in response to multiple biotic stresses despite the apparent absence of phenotypic correlations in the components of resistance [41].

2.3. Genetic Edition Coupled with Gene Drives May Enable Tree Defense Responses

Genetic drift refers to random allelic fluctuations within genepools [51]. It is typically a consequence of limited population size and rampant selection, and thus becomes stronger in secluded hosts and pathogens’ populations. Rare alleles are likely to disappear completely from populations, while previously polymorphic loci might become fixed. Remarkably, in some cases, pathogens may overcome natural genetic drift by utilizing genetic elements from their host as a way to develop resistance to plant defenses. For instance, whitefly, through a horizontal gene transfer event, acquired the plant-derived phenolic glycoside malonyltransferase gene (BtPMaT1), which allows whiteflies to neutralize phenolic glycosides [52].

On the other hand, modern CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology is capable of modifying the immune response function in eukaryotic cells via a highly specific RNA-guided complex [53]. This technology has broad applications in all biological fields, including tree pathology [54]. Bottlenecks are the availability of fine-mapped candidate genes for resistance with major effects, in vitro protocols for tissue culture, and legal regulation [55]. Still, the prospect for gene editing remains open. Interestingly, coupling gene editing with selfish elements in Mendelian segregation distortion due to meiotic drive [56] may efficiently introgress resistance at the population level [57] in a snowball manner [58]. Although promising, combining gene editing with gene drives remains speculative because factual trajectories may prove undesired.

2.4. Harnessing Data Access

Joint research efforts to study more systematically the genomics of forest pathology across the enviromics continuum must be envisioned [59]. At the genomic and breeding level, similar initiatives already exist, such as the European EVOLTREE consortium (http://www.evoltree.eu/, accessed on 16 September 2021), and North Carolina State University’s Central America and Mexico Coniferous Resources Cooperative (CAMCORE, https://camcore.cnr.ncsu.edu/, accessed on 16 September 2021) a not-for-profit international tree breeding organization partnered with private companies in the forestry sector around the world. Both alliances may serve as inspiration to build a stronger networking around breeding for biotic resistance in forest trees. Ultimately, promoting more of these partnership efforts will enhance multi-locality trials and data sharing among countries [60], while improving the understanding of the dynamics of co-evolutionary antagonistic interactions in forest ecosystems through genomic, ecological, and evolutionary studies.

3. Conclusions

-

Forest pathology must start integrating more thoroughly disciplines that allow understanding the biology and natural evolution of trees under biotic stress, seeking the conservation of the mechanisms by which species have defended themselves from biotic antagonistic agents.

-

Polygenetic biotic resistance must be acknowledged as an equally plausible pre-adaptation as Mendelian inheritance.

-

Another prerogative must focus on deepening our ecological understating at the pathogen–species–environment interface, while better integrating this classical PDT paradigm with the modern disciplines of forest genomics, molecular biology, phylo-geography, and predictive breeding (i.e., genomic prediction).

-

Promoting open access and information agreements among national and international parties (i.e., research centers, tree breeding cooperatives, and industries form the forestry sector) is equally relevant to build more cohesive input datasets to ultimately leverage these ‘big data’ integrative approaches for forest pathology breeding.

References

- Cobb, R.C.; Metz, M.R. Tree Diseases as a Cause and Consequence of Interacting Forest Disturbances. Forests 2017, 8, 147.

- Polle, A.; Rennenberg, H. Physiological Responses to Abiotic and Biotic Stress in Forest Trees. Forests 2019, 10, 711.

- Isabel, N.; Holliday, J.A.; Aitken, S.N. Forest genomics: Advancing climate adaptation, forest health, productivity, and conservation. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 3–10.

- Holliday, J.A.; Aitken, S.N.; Cooke, J.E.K.; Fady, B.; Gonz Alez-Martinez, S.C.; Heuertz, M.; Jaramillo-Correa, J.P.; Lexer, C.; Staton, M.; Whetten, R.W.; et al. Advances in ecological genomics in forest trees and applications to genetic resources conservation and breeding. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 706–717.

- Tuskan, G.A.; Groover, A.T.; Schmutz, J.; DiFazio, S.P.; Myburg, A.; Grattapaglia, D.; Smart, L.B.; Yin, T.; Aury, J.-M.; Kremer, A.; et al. Hardwood Tree Genomics: Unlocking Woody Plant Biology. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1799.

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 430–439.

- Teshome, D.T.; Zharare, G.E.; Naidoo, S. The Threat of the Combined Effect of Biotic and Abiotic Stress Factors in Forestry Under a Changing Climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11.

- Mphahlele, M.M.; Isik, F.; Hodge, G.R.; Myburg, A.A. Genomic Breeding for Diameter Growth and Tolerance to Leptocybe Gall Wasp and Botryosphaeria/Teratosphaeria Fungal Disease Complex in Eucalyptus grandis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 1–15.

- Sniezko, R.; Koch, J. Breeding trees resistant to insects and diseases: Putting theory into application. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3377–3400.

- Healey, A.L.; Shepherd, M.; King, G.J.; Butler, J.B.; Freeman, J.S.; Lee, D.J.; Potts, B.M.; Silva-Junior, O.B.; Baten, A.; Jenkins, J.; et al. Pests, diseases, and aridity have shaped the genome of Corymbia citriodora. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 537.

- Fisher, R. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1930.

- Van Valen, L. A new evolutionary law. Evol. Theory 1973, 1, 1–30.

- Papkou, A.; Guzella, T.; Yang, W.; Koepper, S.; Pees, B.; Schalkowski, R.; Barg, M.-C.; Rosenstiel, P.C.; Teotónio, H.; Schulenburg, H. The genomic basis of Red Queen dynamics during rapid reciprocal host–pathogen coevolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 923–928.

- Telford, A.; Cavers, S.; Ennos, R.A.; Cottrell, J.E. Can we protect forests by harnessing variation in resistance to pests and pathogens? Forestry 2015, 88, 3–12.

- Marsh, J.I.; Hu, H.; Gill, M.; Batley, J.; Edwards, D. Crop breeding for a changing climate: Integrating phenomics and genomics with bioinformatics. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1677–1690.

- Cortés, A.J.; López-Hernández, F.; Osorio-Rodriguez, D. Predicting Thermal Adaptation by Looking Into Populations’ Genomic Past. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 1093.

- Pautasso, M. Geographical genetics and the conservation of forest trees. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009, 11, 157–189.

- Resende, M.D.V.; Resende, M.F.R., Jr.; Sansaloni, C.P.; Petroli, C.D.; Missiaggia, A.A.; Aguiar, A.M.; Abad, J.M.; Takahashi, E.K.; Rosado, A.M.; Faria, D.A.; et al. Genomic selection for growth and wood quality in Eucalyptus: Capturing the missing heritability and accelerating breeding for complex traits in forest trees. New Phytol. 2012, 194, 116–128.

- Aitken, S.N.; Whitlock, M.C. Assisted Gene Flow to Facilitate Local Adaptation to Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 44, 367–388.

- Mahony, C.R.; MacLachlan, I.R.; Lind, B.M.; Yoder, J.B.; Wang, T.; Aitken, S.N. Evaluating genomic data for management of local adaptation in a changing climate: A lodgepole pine case study. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 116–131.

- Manel, S.; Schwartz, M.K.; Luikart, G.; Taberlet, P. Landscape genetics: Combining landscape ecology and population genetics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 189–197.

- Garbelotto, M.; Gonthier, P. Variability and Disturbances as Key Factors in Forest Pathology and Plant Health Studies. Forests 2017, 8, 441.

- Eldridge, K. Tropical Forest Genetics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1975; Volume 255, ISBN 9783540373964.

- Meyer, F.E.; Shuey, L.S.; Naidoo, S.; Mamni, T.; Berger, D.K.; Myburg, A.A.; van den Berg, N.; Naidoo, S. Dual RNA-Sequencing of Eucalyptus nitens during Phytophthora cinnamomi Challenge Reveals Pathogen and Host Factors Influencing Compatibility. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 191.

- Naidoo, S.; Külheim, C.; Zwart, L.; Mangwanda, R.; Oates, C.N.; Visser, E.A.; Wilken, F.E.; Mamni, T.B.; Myburg, A.A. Uncovering the defence responses of Eucalyptus to pests and pathogens in the genomics age. Tree Physiol. 2014, 34, 931–943.

- Naidoo, S.; Slippers, B.; Plett, J.M.; Coles, D.; Oates, C.N. The road to resistance in forest trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1–8.

- Gamboa, O.M.; Valverde, Y.B.; Parajeles, F.R.; Córdoba, G.T.; Vanegas, D.C.; Mora, R.C. Cultivo de Especies Maderables Nativas de alto Valor para Pequeños y Medianos Productores; Costa Rica: San José, CA, USA, 2015.

- Lascoux, M.; Glémin, S.; Savolainen, O. Local Adaptation in Plants. eLS 2016, 1–7.

- Cortés, A.J.; Waeber, S.; Lexer, C.; Sedlacek, J.; Wheeler, J.A.; van Kleunen, M.; Bossdorf, O.; Hoch, G.; Rixen, C.; Wipf, S.; et al. Small-scale patterns in snowmelt timing affect gene flow and the distribution of genetic diversity in the alpine dwarf shrub Salix herbacea. Heredity 2014, 113, 233–239.

- Sedlacek, J.F.; Bossdorf, O.; Cortés, A.J.; Wheeler, J.A.; van Kleunen, M. What role do plant–soil interactions play in the habitat suitability and potential range expansion of the alpine dwarf shrub Salix herbacea? Basic Appl. Ecol. 2014, 15, 305–315.

- Little, C.J.; Wheeler, J.A.; Sedlacek, J.; Cortés, A.J.; Rixen, C. Small-scale drivers: The importance of nutrient availability and snowmelt timing on performance of the alpine shrub Salix herbacea. Oecologia 2016, 180, 1015–1024.

- Wheeler, J.A.; Schnider, F.; Sedlacek, J.; Cortés, A.J.; Wipf, S.; Hoch, G.; Rixen, C. With a little help from my friends: Community facilitation increases performance in the dwarf shrub Salix herbacea. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2015, 16, 202–209.

- Anderson, J.T.; Lee, C.-R.; Rushworth, C.A.; Colautti, R.I.; Mitchell-Olds, T. Genetic trade-offs and conditional neutrality contribute to local adaptation. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 699–708.

- Boyle, E.A.; Li, Y.I.; Pritchard, J.K. An Expanded View of Complex Traits: From Polygenic to Omnigenic. Cell 2017, 169, 1177–1186.

- Barghi, N.; Hermisson, J.; Schlötterer, C. Polygenic adaptation: A unifying framework to understand positive selection. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 769–781.

- Csilléry, K.; Rodríguez-Verdugo, A.; Rellstab, C.; Guillaume, F. Detecting the genomic signal of polygenic adaptation and the role of epistasis in evolution. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 606–612.

- Cortés, A.J.; Restrepo-Montoya, M.; Bedoya-Canas, L.E. Modern Strategies to Assess and Breed Forest Tree Adaptation to Changing Climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1606.

- Myburg, A.A.; Hussey, S.G.; Wang, J.P.; Street, N.R.; Mizrachi, E. Systems and Synthetic Biology of Forest Trees: A Bioengineering Paradigm for Woody Biomass Feedstocks. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 775.

- Miska, E.A.; Ferguson-Smith, A.C. Transgenerational inheritance: Models and mechanisms of non–DNA sequence–based inheritance. Science 2016, 354, 59–63.

- Crossa, J.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuevas, J.; Montesinos-López, O.; Jarquín, D.; de los Campos, G.; Burgueño, J.; González-Camacho, J.M.; Pérez-Elizalde, S.; Beyene, Y.; et al. Genomic Selection in Plant Breeding: Methods, Models, and Perspectives. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 961–975.

- Capador-Barreto, H.D.; Bernhardsson, C.; Milesi, P.; Vos, I.; Lundén, K.; Wu, H.X.; Karlsson, B.; Ingvarsson, P.K.; Stenlid, J.; Elfstrand, M. Killing two enemies with one stone? Genomics of resistance to two sympatric pathogens in Norway spruce. Mol. Ecol. 2021.

- Desta, Z.A.; Ortiz, R. Genomic selection: Genome-wide prediction in plant improvement. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 592–601.

- Grattapaglia, D.; Silva-Junior, O.B.; Resende, R.T.; Cappa, E.P.; Müller, B.S.F.; Tan, B.; Isik, F.; Ratcliffe, B.; El-Kassaby, Y.A. Quantitative Genetics and Genomics Converge to Accelerate Forest Tree Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1693.

- Shi, A.; Gepts, P.; Song, Q.; Xiong, H.; Michaels, T.E.; Chen, S. Genome-Wide Association Study and Genomic Prediction for Soybean Cyst Nematode Resistance in USDA Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Core Collection. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12.

- Westbrook, J.W.; Zhang, Q.; Mandal, M.K.; Jenkins, E.V.; Barth, L.E.; Jenkins, J.W.; Grimwood, J.; Schmutz, J.; Holliday, J.A. Optimizing genomic selection for blight resistance in American chestnut backcross populations: A trade-off with American chestnut ancestry implies resistance is polygenic. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 31–47.

- Spindel, J.E.; Begum, H.; Akdemir, D.; Collard, B.; Redoña, E.; Jannink, J.-L.; McCouch, S. Genome-wide prediction models that incorporate de novo GWAS are a powerful new tool for tropical rice improvement. Heredity 2016, 116, 395–408.

- Scott, M.F.; Ladejobi, O.; Amer, S.; Bentley, A.R.; Biernaskie, J.; Boden, S.A.; Clark, M.; Dell’Acqua, M.; Dixon, L.E.; Filippi, C.V.; et al. Multi-parent populations in crops: A toolbox integrating genomics and genetic mapping with breeding. Heredity 2020, 125, 396–416.

- Arenas, S.; Cortés, A.J.; Mastretta-Yanes, A.; Jaramillo-Correa, J.P. Evaluating the accuracy of genomic prediction for the management and conservation of relictual natural tree populations. Tree Genet. Genomes 2021, 17, 12.

- Reyes-Herrera, P.H.; Muñoz-Baena, L.; Velásquez-Zapata, V.; Patiño, L.; Delgado-Paz, O.A.; Díaz-Diez, C.A.; Navas-Arboleda, A.A.; Cortés, A.J. Inheritance of Rootstock Effects in Avocado (Persea americana Mill.) cv. Hass. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11.

- de Sousa, I.C.; Nascimento, M.; Silva, G.N.; Nascimento, A.C.C.; Cruz, C.; Silva, F.F.; de Almeida, D.P.; Pestana, K.; Azevedo, C.F.; Zambolim, L.; et al. Genomic prediction of leaf rust resistance to Arabica coffee using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Agric. 2021, 78.

- Latta, R.G.; Linhart, Y.B.; Mitton, J.B. Cytonuclear Disequilibrium and Genetic Drift in a Natural Population of Ponderosa Pine. Genetics 2001, 158, 843–850.

- Xia, J.; Guo, Z.; Yang, Z.; Han, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Yang, F.; Wu, Q.; Xie, W.; et al. Whitefly hijacks a plant detoxification gene that neutralizes plant toxins. Cell 2021, 184, 1693–1705.

- Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346.

- Dort, E.N.; Tanguay, P.; Hamelin, R.C. CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing: An Unexplored Frontier for Forest Pathology. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1–14.

- Eriksson, D.; Ortiz, R.; Visser, R.G.F.; Vives-Vallés, J.A.; Prieto, H. Editorial: Leeway to Operate With Plant Genetic Resources. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 911.

- Ågren, J.A.; Clark, A.G. Selfish genetic elements. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14.

- Kyrou, K.; Hammond, A.M.; Galizi, R.; Kranjc, N.; Burt, A.; Beaghton, A.K.; Nolan, T.; Crisanti, A. A CRISPR–Cas9 gene drive targeting doublesex causes complete population suppression in caged Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 1062–1066.

- Scudellari, M. Self-destructing mosquitoes and sterilized rodents: The promise of gene drives. Nature 2019, 571, 160–162.

- Crossa, J.; Fritsche-Neto, R.; Montesinos-Lopez, O.A.; Costa-Neto, G.; Dreisigacker, S.; Montesinos-Lopez, A.; Bentley, A.R. The Modern Plant Breeding Triangle: Optimizing the Use of Genomics, Phenomics, and Enviromics Data. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12.

- Spindel, J.E.; McCouch, S.R. When more is better: How data sharing would accelerate genomic selection of crop plants. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 814–826.

More

Information

Subjects:

Forestry

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

976

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

09 Oct 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No