| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | xin sui | + 6002 word(s) | 6002 | 2021-09-18 08:15:31 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -20 word(s) | 5982 | 2021-09-28 10:27:09 | | |

Video Upload Options

Due to the development of the petroleum industrial, numerous petroleum pollutants are discharged into the soil, destroying the structure and properties of the soil, and even endangering the health of plants and humans. Microbial remediation and combined microbial methods remediation of petroleum-contaminated soil are currently recognized remediation technologies, which have the advantages of no secondary pollution, low cost and convenient operation. This entry includes the sources and composition of petroleum pollutants and their harm to soil, plants and humans. Subsequently, the focus is on the mechanism of microbial method and combined microbial methods to degrade petroleum pollutants. Finally, the challenges of the current combined microbial methods are pointed out.

1. Introduction

Petroleum enters the soil environment through processes such as extraction com, processing and transportation (pipe rupture) [1][2]. Toxic and harmful aliphatic, cycloaliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons are the main pollutants of petroleum-contaminated soil [3]. They reduce the diversity of plants and microorganisms in the soil, destroy soil fertility, affect soil ecological balance, and even endanger human health [4]. The germination of crops in high petroleum-contaminated soil is delayed, the chlorophyll content is low, and some crops die [5]. In addition, pollutants can enter the human body through breathing, skin contact, or eating food containing petroleum contaminants, causing contact dermatitis, visual and auditory hallucinations, and gastrointestinal diseases, and even greatly increasing the risk of children suffering from leukemia. Although some low-molecular-weight hydrocarbon pollutants will be weathered and degraded over time, high-molecular-weight hydrocarbon pollutants, due to their hydrophobicity, exist in the soil for a long time and cause secondary pollution to the surrounding environment [6][7]. Therefore, repairing petroleum-contaminated soil has become a topic of widespread concern.

At present, the methods to treat petroleum-contaminated soil include incineration, landfill, leaching, chemical oxidation and microbial treatment. These remediation technologies can extract, remove, transform or mineralize petroleum pollutants in the polluted environment into a less harmful, harmless and stable form [8]. Although 99.0% and 92.3% of total petroleum hydrocarbons(TPH) can be removed by incineration and chemical oxidation, these repair techniques still have drawbacks [9][10]. Toxic substances such as dioxins, furans, polychlorinated biphenyls and volatile heavy metals from incomplete incineration of petroleum will be released into the atmosphere [11]. At the same time, as the incineration temperature rises from 200°C to 1,050°C, the carbon in the soil is lost 49-98%, and the organic matter and carbonate in the soil are decomposed into light hydrocarbons (C2H2, C2H4 and CH4) and carbon dioxide separately [12][13]. After chemically oxidizing the petroleum pollutants in the soil with 5% hydrogen peroxide and persulfate for 10 days, the total number of soil microorganisms decreased from 104CFU g−1 to 103 CFU g−1 and 102 CFU g−1 separately. And the bacteria grow slowly in the next 10 days [14]. The incomplete combustion of petroleum increases the hidden dangers of environmental safety, while the loss of carbon and organic matter limits the recovery ability of the soil ecosystem. The addition of oxidants will inhibit the growth of soil microorganisms. Therefore, while reducing the concentration of soil petroleum pollutants, it will not cause secondary pollution to the soil and the surrounding environment, which has become the main consideration for selecting remediation technologies.

Microbial remediation is inexpensive, and it can completely mineralize organic pollutants into carbon dioxide, water, inorganic compounds and cell proteins, or convert complex organic pollutants into other simpler organics [15]. Microorganisms can use organic pollutants as the sole carbon source to grow and metabolize, so as to achieve the purpose of degrading organic pollutants in the soil [16][17]. Within 150-270d, microorganisms degraded 62-75% of petroleum hydrocarbons in the soil [18][19]. Within 60 days, 2.3-6.8% of petroleum hydrocarbons were degraded by free microorganisms, but when biochar was used as a carrier, 7.2-30.3% of petroleum hydrocarbons were degraded [20]. On day 20, the degradation rate of petroleum in the immobilized system (sodium alginate-diatomite beads) was as high as 29.8%, while the degradation rate of free cells was 21.2% [21]. At 4°C and 10°C, the microbial mineralization of hexadecane produced 45% CO2, but at 25°C, the microbial mineralization of hexadecane produced 68% CO2 within 50 days [22]. When the soil salinity is higher than 8%, and the pH value is lower than 4 and higher than 9, the activity of Acinetobacter baylyi ZJ2 is affected, and a certain amount of lipopeptide surfactant cannot be produced, thereby reducing the degradation of petroleum by microorganisms [23].

In summary, extreme environmental conditions (soil environmental temperature less than 10°C, pH less than 4 and greater than 9) reduce microbial activity, which reduces the removal effect of petroleum pollutants. Current research shows that the best conditions for microbial remediation of oily soil are: pH 5.5-8.8, temperature 15-45°C, oxygen content 10%, soil type: low clay or silt content, C/N/P: 100:10:1 [24][25]. Microbial remediation has problems such as long remediation time and poor remediation effect of free microorganisms. In order to overcome the difficulty of microbial remediation of petroleum in the soil, the microbial combination method is used to improve the biodegradation efficiency of microorganisms.

This entry first discusses the source, classification and composition of hydrocarbon pollution in soil, as well as its impact on the environment and human health. Subsequently, the types and advantages of combined microbial repair methods are discussed. The focus is on the microbial remediation mechanism of petroleum pollutants and the microbial-biochar/nutrients/plants interaction in the microbial combined method. Finally, the advantages and challenges of the current microbial combined method repair technology are proposed.

2. Petroleum contaminated soil

2.1. Sources of petroleum pollutants

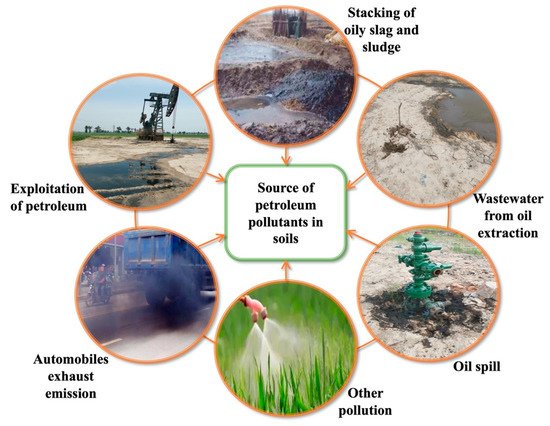

As shown in Fig. 1, petroleum pollutants leak to the soil through petroleum extraction, petroleum residue and sludge stacking, oily wastewater and accidental petroleum spills, automobile exhaust emissions, and other methods (using pesticides) [26]. Petroleum spills are one of the main sources of hydrocarbon pollution in the soil. The global natural petroleum leakage is estimated to be 600,000 metric tons per year [27]. It is estimated that 3.5 million locations in Europe may be contaminated by petroleum [28]. About 4.8 million hectares of soil petroleum content in China may exceed the safe value [29]. Different countries and regions have different sampling and transportation methods, and the sources and degrees of petroleum pollution are also different. Moreover, through the washing and leaching of rainwater, the pollutants are leached into the surrounding and deep soil in the horizontal and vertical directions, and even into the groundwater system.

Compared with high-molecular-weight hydrocarbons, low-molecular-weight hydrocarbons are more volatile and easier to penetrate into groundwater, but volatilization and permeability are affected by the physical and chemical properties of soil, climate, and vegetation [28]. Although low-molecular-weight hydrocarbons will weather and degrade over time, high-molecular-weight hydrocarbons can remain in the soil for a long time due to their hydrophobicity [6][7]. The natural decay half-life of petroleum hydrocarbons increases as the concentration of petroleum hydrocarbons increases (when the petroleum concentration is 250mg/L, the half-life is 217d) [30] . As the molecular weight increases, the natural half-life of alkane and aromatic contaminants increases. For example, the half-life of three-ring molecule phenanthrene under natural conditions is 16 to 126 days, while the half-life of five-ring molecule benzo[α]pyrene is 229 to 1,400 days [31]. Although the contaminated soil itself has some special microorganisms that can biodegrade and bio-transform these hydrocarbons, assimilating them into biomass in the soil [32][33]. However, due to the non-polarity and chemical inertness of pollutants, small amounts of hydrocarbons (such as long chain and high molecular weight hydrocarbons) are still difficult to handle in the environment [34].

2.2. Composition of petroleum pollutants

Petroleum-contaminated soil usually consists of petroleum, water and solid particles. Petroleum contaminants are usually shown in the form of water-in-petroleum (W/O). Petroleum is composed of a mixture of different hydrocarbons. The chemical elements that make up petroleum are mainly carbon (83% ~ 87%), hydrogen (11% ~ 14%), and the rest are sulfur (0.06% ~ 0.8%) and nitrogen (0.02% ~ 1.7%), oxygen (0.08% ~ 1.82%) and trace metal elements (nickel, vanadium, iron, antimony, etc.) [35]. Hydrocarbons formed by the combination of carbon and hydrogen constitute the main component of petroleum, accounting for about 95% to 99%. Various hydrocarbons are classified according to their structure: alkanes, cycloalkanes, and aromatic hydrocarbons.

Alkanes are the main components of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel [36][37]. The molecular structure is linear, branched and cyclic. The general formula of linear-alkanes is CnH2n+2, the general formula of branched alkanes is CnH2n+2(n > 2), and the general formula of cycloalkanes is CnH2n( n > 3). Aromatics are found in gasoline, diesel, lubricants, kerosene, tar and asphalt [38]. The molecular structure is similar to cycloalkanes, but they contain at least one benzene ring [39]. The general formula of aromatics is CnH2n-6.

Petroleum comes from the source rock bitumen, and the heaviest and most polar molecules in the asphaltene are strongly adsorbed on the source rock and are difficult to discharge into the reservoir. Therefore, saturated hydrocarbons with the lowest polarity are the most common, followed by aromatics [40]. The degradability of hydrocarbons is affected by their molecular weight. The bioavailability of low-molecular-weight hydrocarbons is higher than that of high-molecular-weight hydrocarbons [41][42]. Therefore, the sensitivity of hydrocarbons to microbial degradation is generally: linear alkanes> branched alkanes> low-molecular-weight aromatics> cyclic alkanes [15][43].

2.3. Toxic effects of petroleum on the environment

Petroleum mainly contains saturates, aromatics and other toxic and harmful hydrocarbons [29]. Specific petroleum pollutants (PAHs, BTEX) that are highly toxic will have a negative impact on soil, plants and humans. High concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons ( PAHs) in the soil can cause toxic effects on terrestrial invertebrates such as tumors, reproduction, development and immunity [44]. Low concentration (10 mg/kg) PAHs can promote tomato growth. However, when the concentration of PAHs was greater than 20 mg/kg, tomato growth was inhibited [45]. Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX) can create problems for nervous system, liver kidney, and respiratory system of human being [46]. Pollutants block soil pores, change the composition and structure of soil organic matter, reduce the activity and diversity of soil microorganisms and plants, and ultimately threaten human health through the food chain [47]. The petroleum in the soil also pollutes the groundwater environment through diffusion and migration, which poses unfavorable pressure on many aspects of the human living environment.

2.3.1. Toxic effects of petroleum on soil

Petroleum destroys the stability of soil ecological structure and function [6], and significantly affects the content of soil moisture, pH, total organic carbon, total nitrogen, exchangeable potassium, and enzyme activity (urease, catalase and dehydrogenase)[48][49][50][51]. As the concentration of pollutants increases, the clay content in the contaminated soil increases [52], the soil porosity decreases, and the impermeability and hydrophobicity increase [53], which inhibits the growth of plant roots and soil the number of bacteria. When the petroleum hydrocarbon content in the soil was 7791 mg/kg, the root length of Lepidium sativum, Sinapis alba, and Sorghum saccharatum was suppressed by 65.1%, 42.3% and 47.3% [54]. Straight-chain alkanes have the greatest influence on the number of bacteria species. The order of influence is as follows: 320.5±5.5(in the control soil)> 289.1±4.7(in the aromatic hydrocarbon-contaminated soil)> 258.6±2.5(in the branched-chain alkane contaminated soil)> 229.7±2.0(in straight-chain and cyclic alkanes hydrocarbons contaminate soil) [55]. Studies have found that benzo[a]pyrene in petroleum is the main pollutant that causes soil salinization and acidification [56].

2.3.2. Toxic effects of petroleum on plants

Petroleum contaminants can penetrate the surface of plants and migrate in the intercellular space and vascular system. Plant roots can absorb petroleum pollutants in the soil, move to leaves and fruits and accumulate, and can also transfer pollutants from the leaves to the roots. Petroleum pollution significantly reduced the germination rate, plant height, leaf area and dry matter yield of corn [56]. Due to the lack of oxygen and nutrients in the contaminated soil, plant growth is retarded, stem length and diameter are shortened, aboveground tissue length is reduced, and root length and plant leaf area changes(depending on the plant species) [57]. Studies have shown that low concentration(10 g/kg) petroleum hydrocarbon can promote plant root vitality, while medium concentration(30 g/kg) and high concentration(50 g/kg) petroleum hydrocarbon can inhibit plant root vitality. At the same time, the chlorophyll content of 50 g/kg petroleum-contaminated soil is nearly 60% lower than that of non-petroleum-contaminated soil [58].

2.3.3. Toxic effects of petroleum on human health

Direct (breathing polluted air and direct contact with skin) or indirect (bathing in contaminated water and eating contaminated food) exposure to petroleum and petroleum products can cause serious health problems to humans [59]. Many petroleum contaminants are toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic, such as benzene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Some aromatics affect the human normal functions of liver and kidney and even causing cancer [60]. And PAHs are highly lipophilic, so they are easily absorbed by mammals through the gastrointestinal tract [44]. Workers who have been exposed to contaminated sites for a long time have symptoms such as fatigue, breathing, eye irritation and headaches, and women have an increased risk of spontaneous abortion [61].

3. Advances in the utilization of microorganisms in petroleum remediation

Search for articles in "web of science" databases,databases contain the Core Collection (WOS), Derwent innovations index(DII), Korean Journal Database (KJD), MEDLINE (MEDLINE), Russian Science Citation Index (RSCI) and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SCIELO) six databases. The searched articles were published limited to 1950-2020. The specific search terms result is “Microbial degradation petroleum”. The search time is September 17, 2020, and the results are statistically analyzed.

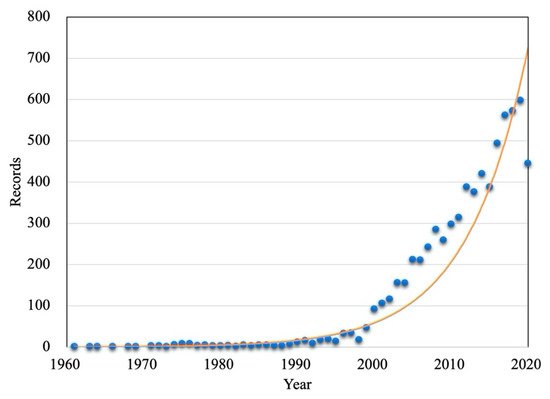

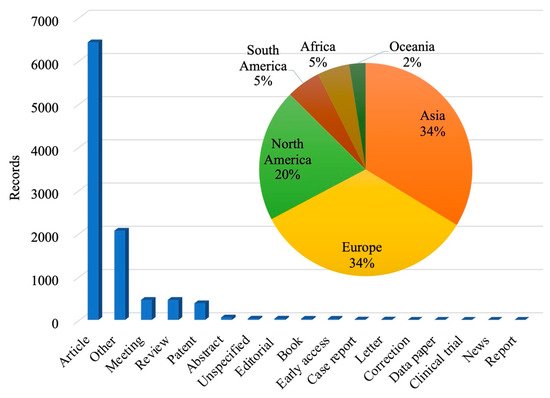

Fig. 2 summarizes the record number of research results of microbial remediation of petroleum pollution from 1950 to 2020. The number of recorded research results has increased year by year, indicating that the microbial remediation technology of petroleum has attracted the attention of scholars at home and abroad in recent years. Fig. 3 Statistics of research output types and the percentage of countries/regions researched. The aggregated data show that the article is the main research output

4. Microbial remediation

Compared with physical and chemical remediation methods, bioaugmentation shows high feasibility and economic applicability [62][63]. Bioaugmentation can be accomplished by introducing lipophilic bacteria [64]. Oleophilic bacteria widely exist in petroleum contaminated environment[6], such as seawater, coastline, sludge and soil. They can use various hydrocarbons as the sole carbon source for growth, while decomposing or mineralizing toxic and harmful petroleum pollutants [65][66].

Currently, studies have shown that a variety of microorganisms can degrade petroleum pollutants, such as Rhodococcus sp., Pseudomonas sp. and Scedosporium boydii [67][68][69]. Strains mainly degrade hydrocarbons through aerobic pathways [70]. Generally, the catabolism of hydrocarbons is faster when oxygen acts as an electron acceptor [71]. The reactions that mediate degradation are oxidation, reduction, hydroxylation and dehydrogenation that occur in aerobic mode. Enzymes such as monooxygenase, dioxygenase, cytochrome P450, peroxidase, hydroxylase and dehydrogenase play an important role in the biodegradation of hydrocarbons [70][72][73][74][75].

At present, microorganisms that degrade alkanes and PAHs in inorganic salt liquid medium have been successfully separated(as shown in Table 1). That microorganism metabolism alkanes and PAHs main through terminal oxidation, subterminal oxidation, ω-oxidation and β-oxidation. Alkanes are main degraded by terminal oxidation pathway. Molecular oxygen is introduced into hydrocarbons by alkane hydroxylase to oxidize terminal methyl to form alcohols, which are further oxidized to aldehydes and fatty acids, and finally, carbon dioxide and water are generated through β-oxidation pathway to form tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA)[76][77][78]. On the contrary, PAHs show strong recalcitrance to biodegradation due to the structural stability. PAHs are main metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzyme mediated mixed functional oxidase system with oxidation or hydroxylation as the first step, and the formation of diols as intermediate products. These intermediates undergo ortho-cleavage or meta-cleavage pathways to form catechol intermediates, which are finally incorporated into the TCA cycle [70][77].

Table 1. Common microorganisms that degrade alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

|

Substrates |

Microorganisms |

Source of strain |

Main findings |

Reference |

|||

|

Substrate concentration |

Incubation conditions |

Degradation rate |

|||||

|

PAHs |

bacteria |

Achromobacter sp.HZ01 |

Crude oil-contaminated seawater, China. |

100mg/kg anthracene, phenanthrene and pyrene. |

109 cells mL-1bacterial suspension /28 °C/150 rpm/30 days. |

Strain remove anthracene, phenanthrene and pyrene about 29.8%, 50.6% and 38.4% respectively. |

[79] |

|

Acinetobacter sp. WSD |

Crude oil-contaminated groundwater, Shanxi province of northern China. |

1 mg/kg phenanthrene, 2 mg/kg fluorine and 0.14 mg/kg pyrene. |

5 % actively growing cells /33 °C/150 rpm/6 days. |

Approximately 90 % of fluorine, 90 % of phenanthrene and 50 % of pyrene were degraded. |

[80] |

||

|

Bacillus subtilis BMT4i (MTCC 9447) |

Automobile contaminated soil, Uttarakhand, India. |

50 g /ml Benzo [a] Pyrene. |

1x108 cells ml-1 /37 °C/120 rpm/28 days. |

Strain started degrading Benzo [a] Pyrene achieving maximum degradation of approximately 84.66 %. |

[81] |

||

|

Caulobacter sp. (T2A12002) |

From King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals Department of Life Sciences laboratory. |

100 ppm pyrene. |

2 ml inoculum suspension(in 100 ml mineral salts) /37 °C and 25 °C /120 rpm/18 days/ pH 5.0 and pH 9.0. |

Strain degraded 35% and 36% of pyrene at 25 °C and 37 °C. |

[82] |

||

|

Enterobacter sp. (MM087) |

Engine oil contaminated soil, Puchong and Seri Kembangan, Selangor Malaysia. |

500 mg/l phenanthrene and 250 mg/l pyrene. |

5% v/v bacterial cells 1x10⁶cells ml-1/37±0.5⁰C/200 rpm/24 hours. |

Strain with 80.2% degradations for phenanthrene and 59.7% degradations for pyrene. |

[83] |

||

|

Klebsiella pneumoniaeAWD5 |

Automobile contaminated soil, Silchar, Assam. |

0.005% PAH (Pyrene, Chrysene, Benzo(a)pyrene). |

OD600=0.4/30°C/140 rpm/9 days. |

Strain degraded pyrene (56.9%), chrysene (36.5%) and benzo(a)pyrene (50.5%), respectively. |

[84] |

||

|

Mycobacterium vanbaalenii PYR-1 |

Oil contaminated sediment and water, the watershed of Redfish Bay near Port Aransas, Tex. |

0.5 ug/ml pyrene. |

1.5x106 cells ml-1/ 24°C /150 rpm/48 to 96 h. |

After incubation, 47.3 to 52.4% of pyrene was mineralized to CO2. |

[85] |

||

|

Raoultella planticola |

Near a car repair station, Hangzhou, China. |

20 mg L−1 pyrene and 10 mg L−1 benzo[a]pyrene. |

2.0 × 108 cells mL−1/30°C /180 rpm/10 days. |

Strain degraded 52.0% of pyrene and 50.8% of benzo[a]pyrene. |

[86] |

||

|

Rhodococcus sp. P14 |

Oil contaminated sediments, Xiamen, China. |

50 mg/L phenanthrene, pyrene and benzo[a]pyrene. |

200 μl cell suspension(in 20ml Inorganic salt medium )/ 30°C /150 rpm/30 days. |

Strain degraded 34% of the pyrene, about 43% of the phenanthrene and 30% of the Benzo[a]pyrene. |

[87] |

||

|

Pseudomonas sp. MPDS |

PAHs and petrochemicals contaminated soil and mud, Tianjin[89]. |

1mg/ml naphthalene, 0.1mg/ml dibenzofuran, 0.1mg/ml dibenzothiophene, 0.1mg/ml fluorene. |

OD600 = 5.0(in 50ml)/25°C /200 rpm/84 h, 96 h and 72 h. |

Strain could completely degrade naphthalene in 84 h. A total of 65.7% dibenzofuran and 32.1% dibenzothiophene could be degraded in 96 h and 40.3% fluorene could be degraded in 72 h. |

[88] |

||

|

Pseudoxanthomonas sp. DMVP2 |

Hydrocarbon contaminated sediment, Gujarat, India. |

300 ppm phenanthrene |

cell suspension (4%, v/v)/ 37 °C/ 150 rpm/72 h. |

Strain was able to degrade 86% phenanthrene. |

[89] |

||

|

Sphinogmonas sp. |

Typical mangrove swamp(surface sediment (0–2 cm)), Ho Chung, Hong Kong. |

5000 mg L-1 phenanthrene. |

180rpm/ 7 days. |

Strain was obtained to degrade 99.4% phenanthrene at the end of 7 days. |

[90] |

||

|

Stenotrophomonas sp. IITR87 |

—1 |

phenanthrene(10ppm), pyrene(10ppm), and benzo-α-pyrene(10ppm). |

200 μl of cells suspension(in 25 ml minimal medium)/ 30 °C/ 175rpm/15 days. |

Strain showed >99, 98 and <50% degradation of phenanthrene, pyrene, and benzo-α-pyrene respectively. |

[91] |

||

|

Streptomyces sp. (ERI-CPDA-1) |

Oil contaminated soil, Chennai, India. |

naphthalene(0.1%), phenanthrene(0.1%). |

3%, v/v cells suspension/30 °C/ 200rpm/7 days. |

Strain could remove 99.14% naphthalene and 17.5% phenanthrene. |

[92] |

||

|

fungus |

Aspergillus sp. RFC-1 |

Rumaila oilfield(surface polluted sludge (1–10 cm)), Basra, Iraq. |

50 mg/L naphthalene, 20 mg/L phenanthrene, 20 mg/L pyrene. |

10% v/v cells suspension/30 °C/ 120rpm/7 days. |

Biodegradation efficiencies of crude oil, naphthalene, phenanthrene, and pyrene were 84.6%, 50.3%, and 55.1%, respectively. |

[93] |

|

|

Nocardia sp. H17-1 |

Oil-contaminated soil |

aliphatic and aromatic(1%, w/v). |

30 °C/6 days. |

The aliphatic and aromatic fractions were degraded 99.0 ± 0.1% and 23.8 ± 0.8%, respectively. |

[94] |

||

|

Penicillium sp. CHY-2 |

Soil, Antarctic. |

100 mg L−1 butylbenzene, naphthalene, acenaphthene, ethylbenzene, and benzo[a]pyrene. |

20 °C/110rpm/28days. |

Strain showed the level of degradation for butylbenzene (42.0%), naphthalene (15.0%), acenaphthene (10.0%), ethylbenzene (4.0%), and benzo[a]pyrene (2.0%). |

[95] |

||

|

Trichoderma sp. |

—1 |

100 mg kg-1 pyrene and benzo(a)pyrene. |

240 h |

Strain degraded 63% of pyrene(100 mg kg-1) and 34% of benzo(a)pyrene(100 mg kg-1) after 240 h of incubation. |

[98] |

||

|

Fusarium sp. |

—1 |

100 mg kg-1 pyrene and benzo(a)pyrene. |

240 h |

Strain degraded 69% of pyrene(100 mg kg-1) and 37% of benzo(a)pyrene(100 mg kg-1) after 240 h of incubation. |

[96] |

||

|

alkanes |

bacteria |

Achromobacter sp.HZ01 |

Crude oil-contaminated seawater, China. |

2% (w/v) diesel oil |

28 °C/150 rpm/10 days. |

Strain degraded the total n-alkanes reached up to 96.6%. |

[79] |

|

Acinetobacter sp.(KC211013) |

Coal chemical industry wastewater treatment plant, northeast China. |

700mg/L alkanes. |

35˚C |

The degradation rate reached 58.7%. |

[97] |

||

|

Bacillus subtilis |

Petroleum-polluted soil, Shengli Oilfield, China. |

0.3% (w/v) crude oil. |

6%(v/v) cells suspension/30 °C/ 150rpm/5 days. |

The results indicated that 30–80% of the n-alkanes (C13–C30) were degraded by strain. |

[98] |

||

|

Pseudomonas sp. WJ6 |

Xinjiang oilfield, China. |

0.5% (w/v) n-alkanes. |

1010 CFU ml-1/ 37 °C/ 180 rpm/20 days. |

N-dodecane (C12) was degraded by 46.65%. 42.62%, 31.69% and 23.62% of C22, C32 and C40 were degraded, respectively. |

[99] |

||

|

Rhodococcus sp. |

Bay of Quinte, Ontario, Canada. |

0.1% (v/v) diesel fuel. |

OD600=0.025/ 0°C/ 150 rpm/ 102 days. |

After 102 days of incubation at 0°C, strain mineralized C12 (8%), C16 (6.1%), C28 (1.6%), and C32 (4.3%). |

[100] |

||

|

fungus |

Cladosporium resinae |

Soil, Australian. |

12.5%(v/v) n-alkanes. |

0.3-0.5ml cells suspension(in 40ml minimal medium)/ 35°C/ 35 days. |

All higher n-alkanes from n-nonane to n-octadecane were assimilated by the fungus. |

[101] |

|

|

Penicillium sp. CHY-2 |

Soil, Antarctic. |

100 mg L−1 decane, dodecane and octane. |

20 °C/110 rpm/28 days. |

Strain was degraded decane (49.0%), dodecane (33.0%) and octane (8.0%). |

[95] |

||

|

actinomycetes |

Gordonia sp. |

Hydrocarbon-contaminated mediterranean shoreline, west coast of Sicily, Italy. |

1 g L-1 eicosane and octacosane. |

30 °C /28 days. |

Eicosane and octacosane were degraded from 53% to 99% in 28 days. |

[102] |

|

|

Tsukamurella sp. MH1 |

Petroleum-contaminated soil, Pitești, Romania. |

0.5% (v/v) liquid alkanes. |

30 °C |

Strain capable to use a wide range of n-alkanes as the only carbon source for growth. |

[103] |

||

1 There is no clear description in the entry.

Low-molecular-weight saturated hydrocarbons and aromatic hydrocarbons are easily degraded by microorganisms, while petroleum hydrocarbons with higher-molecular-weight have strong resistance to microbial degradation [104]. The order of microbial degradation is as follows n-alkanes > branched-chain alkanes > branched alkenes> low-molecular-weight n-alkyl aromatics > monoaromatics > cyclic alkanes > polynuclear aromatics > asphaltenes [105]. After 45 days of degradation of asphaltenes by Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the methylene content in asphaltenes decreased by 14% and 8%, respectively [105]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa can degrade 63.8% of n-hexadecane within 60 days [106]. Most of the microbial degradation of petroleum pollutants experiments remain in the laboratory tests in the mineral basal medium (liquid)(as shown in Table 1 ), and lack of application in actual petroleum contaminated soil. At the same time, a single bioremediation technology faces challenges such as long repair time, unstable microbial activity and poor degradation of free microorganisms. Therefore, the combined microbial methods (synergistic repair involving microorganisms in the degradation process) is used to improve degradation effect and practical applicability.

5. Combined microbial methods remediation

The microbial combination method is mainly summarized into three categories: microorganism-physical, microorganism-chemical, and microorganism-biology. Many materials and methods have been used in microbial combined method to degrade petroleum-contaminated soil (Table 2). Due to the hydrophobicity and fluidity of petroleum, most remediation combined methods are designed to improve microbial activity and aeration of contaminated soil. Therefore, electric field, nutrients, biocarrier, biochar, biosurfactants and plants were added to the petroleum-contaminated soil to improve the degradation rate of the system [107][108][109]

|

Table 2. The microbial combined materials and methods were used for the degradation of petroleum-contaminated soils

|

|||||

|

Methods |

Materials |

Main findings |

Reference |

||

|

Substrate concentration |

Incubation conditions |

Degradation rate |

|||

|

microorganism-physical |

biochar(walnut shell biochar (900°C)/ pinewood biochar (900°C)) |

24,000, 16,000 and 21,000 mg/kg total petroleum hydrocarbons(TPH). |

50 g soil/ 5% pinewood biochar/ C:N:P at 800:13.3:1/ 25 °C/ 60 days. |

The combined remediation of biochar and fertilizer reduces the TPH in the soil to 10000 mg/kg(the US EPA clean up standard). |

[107] |

|

biochar(rice straw (500 °C)) |

16,300 mg kg−1 TPH (saturated hydrocarbons, 8260 mg kg−1; aromatic hydrocarbons, 5130 mg kg−1; polar components, 2910 mg kg−1). |

1,000 g soil/ 2% (w/w) biochar/ 60% water holding capacity/ C:N:P ratio 100:10:5/ 80 days. |

TPH removal rate was 84.8%. |

[110] |

|

|

electrokinetics |

12,500 mg/kg TPH. |

600 g soil/C:N:P 100:10:1/ 30 days. |

The degradation rate of TPH was 88.3%. |

[108] |

|

|

β-cyclodextrin |

1,000mg/kg PAHs |

1.5, 3.0, 5.0 mmol/kgβ-cyclodextrin/ 25 °C. |

Compared with the co-metabolism of glucose, the addition of β-cyclodextrin more strongly enhanced oil remediation in soil. |

[111] |

|

|

bulking agents (chopped bermudagrass-hay/sawdust/vermiculite) |

10% TPH |

C:N:P 1000:10:1/ 15-35°C/ 12 weeks. |

Tillage and adding bulking agents enhanced remediation of oil-contaminated soil. The most rapid rate of remediation occurred during the first 12 weeks, where the TPH decreased 82% and the initial concentration of TPH was 10%. |

[112] |

|

|

aeration (tillage/forced aeration). |

|||||

|

biocarrier(activated carbon/zeolite) |

49.81 mg g−1 TPH |

800g soil/ 50 g biocarrier + 150 mL planktonic bacterial culture / C:N:P 100:10:1/ 30 °C/ 33 days. |

Biocarrier enhanced the biodegradation of TPH, with 48.89% removal, compared to natural attenuation with 13.0% removal. |

[113] |

|

|

microorganism-chemical |

biostimulation |

19.8 ± 0.38 g kg−1 TPH |

0.8 kg soil/ 108 cfu g−1 petroleum degrading flora/ 15% soil moisture/ C:N:P 100:10:1/ 24 °C/ 12 weeks. |

Biostimulation achieved 60% oil hydrocarbon degradation. |

[114] |

|

biosurfactants(rhamnolipids) |

47.5 g kg−1 TPH |

500 g soil/ 7 g of rhamnolipids (dissolved in 1 L deionized water)/ 500 ml bacterial consortium (in sterile 0.9% NaCl solution)/ 20% (w/w) moisture content/ C:N:P 100:10:1/ 30 days. |

TPH degradation of 77.6% was observed in the soil inoculated with hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria supplemented with rhamnolipids and nutrients. |

[109] |

|

|

permanganate/activated persulfate/modified-Fenton/Fenton |

263.6 ± 73.3 and 385.2 ± 39.6 mg·kg−1Σ16 PAHs. |

50 g soil/ the final volume of the Milli-Q water and oxidant was 100 mL/ 150 rpm/ 15 days. |

The removal efficiency of PAHs was ordered: permanganate (90.0%–92.4%) > activated persulfate (81.5%–86.54%) > modified Fenton (81.5%–85.4%) > Fenton (54.1%–60.0%). |

[10] |

|

|

activator (low ammonia and acetic acid) |

29,500 mg kg−1 TPH. |

18–20% moisture content/ 12 weeks. |

Macro-alkanes in soils were efficiently degraded. |

[115] |

|

|

microorganism-biology |

Lolium perenne |

6.19% TPH |

750 g soil/ 20–30% moisture content/ 162 days. |

The results show that the combination of ryegrass with mixed microbial strains gave the best result with a degradation rate of 58%. |

[116] |

|

Medicaga sativa |

30%(40% TPH oily sludge)+70% non-pollution soil. |

1kg soil/ N:P 10:1/ 75-80% moisture content/ 60 days. |

Consortium degraded more than 63% TPH. |

[117] |

|

|

Medicaga sativa/vicia faba/Lolium perenne |

1.13% TPH. |

2kg soil/ 18 months. |

The TPH degradation in the soil cultivated with broad beans and alfalfa was 36.6% and 35.8%, respectively, compared with 24% degradation in case of ryegrass. |

[118] |

|

|

biopiles(bark chips) |

700 mg kg-1 TPH |

soil to bulking agent was approximately 1:3/ 15–20°C / 5 months. |

The TPH content in the pile with oil-contaminated soil decreased with 71%. |

[119] |

|

|

biopiles(peanut hull powder) |

29,500 mg kg−1 TPH |

5 kg of soil/15% w/w peanut hull powder/ 18–20% moisture content/ C:N:P 100:10:1/ 25–30 °C/ 12 weeks. |

Biodegradation was enhanced with free-living bacterial culture and biocarrier with a TPH removal ranging from 26% to 61%. |

[120] |

|

|

biopiles(food waste) |

2% diesel oil |

soil [77% (w/w)] and food waste [23% (w/w)]/ C:N 11:1/ 13 days. |

84% of the TPH was degraded, compared with 48% of removal ratio in control reactor without inoculum. |

[121] |

|

|

earthworms (Eisenia fetidaAllolobophora chlorotica/Lumbricus terrestris) |

10,000 mg/kg TPH |

1000 g soil/ ten adult worms per container/ 28 days. |

The TPH concentration decreased by 30–42% in samples with L. terrestris, by 31–37% in samples with E. fetida, and by 17–18% in samples with A. chlorotica. |

[122] |

|

Figure 4. The frequency of citations of the article with three microbial combined methods for remediation of oil contaminated soil.

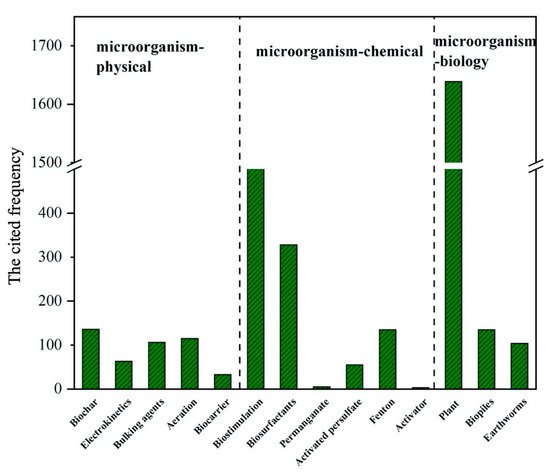

Through six databases in “web of science”, the time limit is limited to 2016-2020. The specific search terms results are “Microbial biochar(electrokinetics/ bulking agents/ aeration/ biocarrier/ biostimulation/ biosurfactants/ permanganate/ activated persulfate/ fenton/ activator/ plant/ biopiles/ earthworms) remediation of petroleum contaminated soil”. The search time is September 17, 2020, and the results are statistically analyzed. Fig. 4 shows the highest citation frequency of articles using the three combined microbial methods to remediate petroleum contaminated soil from 2016 to 2020. The compiled data indicate that microorganism-biochar, microorganism-nutrients and microorganism-plant combined microbial methods have been widely adopted for hydrocarbon degradation in current research.

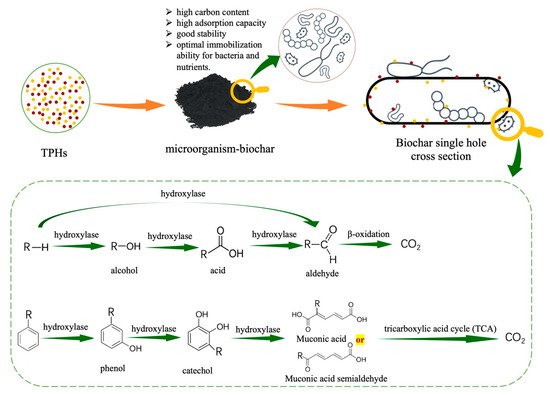

5.1. Microorganism-biochar interactions in remediation of hydrocarbons

Biochar has a high carbon content, strong adsorption capacity, good stability, and the best immobilization capacity for bacteria and nutrients. The porous structure of biochar can provide attachment sites and suitable habitats for the survival of microorganisms. The addition of biochar of different properties to the soil is conducive to the enrichment of specific functional groups of microorganisms and the enhancement of biological activity [123][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][124][125]. The functional groups on the surface of biochar, easily decomposable carbon source and nitrogen source help to improve the activity of microorganisms and affect the growth, development and metabolism of microorganisms. Using biochar to immobilize microorganisms with different functional characteristics can strengthen the release of some nutrients in the soil and improve the degradation efficiency of pollutants. Studies have shown that biochar can absorb pollutants in petroleum, thereby reducing soil toxicity, and has no obvious negative impact on soil microorganisms [112]. In addition, the joint input of biochar and petroleum-degrading bacteria improves the diversity of microbial populations and the bioavailability of hydrocarbons [126].

Figure 5. Proposed mechanism for the microbial metabolization of alkanes and aromatic hydrocarbons.

Fig. 5 outlines the general interactions that occur in the microorganism-biochar remediation of contaminants. Microorganism-biochar remediation mechanism can be divided into the adsorption, biodegradation and mineralization or a combination of these three methods. Due to the large specific surface area and rough surface structure of biochar, it is beneficial to the attached microorganisms to secrete biofilm, which increases the adsorption and degradation rate of hydrocarbons, and also increases the abundance of soil and active microorganisms. At the same time, studies have shown that fixed bacteria can use carbon chains more widely than free bacteria, and the removal rate of hydrocarbons has increased by about 21%-49% [126].

5.2. Microorganism-nutrients interactions in remediation of hydrocarbons

The input of a large amount of carbon sources (petroleum pollutants) often leads to the rapid depletion of the available pools of the main inorganic nutrients (such as nitrogen(N) and phosphorus(P)) in the soil, while the essential nutrients (such as N, P and terminal electron acceptors (TEA), etc.) is a key factor in reducing the rate of microbial metabolism [88]. Although the microorganisms in the soil show obvious pollution remediation potential, the lack of essential nutrients or the lack of stimulation of the degradation metabolic pathways leads to the inhibition or delay of microbial remediation. Therefore, it is necessary to add nutrients from external sources to stimulate the biodegradation of inorganic pollutants [127].

If the soil environment is anaerobic for a long time and the carbon content of the pollutant is high, the metabolism of denitrifying bacteria in the soil will reduce the total nitrogen content of the soil, thereby limiting this nutrient [128]. Studies have shown that the content of ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) and phosphorus (PO43−-P) in the soil drops rapidly after 15 days of restoration [129]. Nitrate has a significant advantage in increasing the potential of soil biodegradation of organic pollutants. Adding N to nutrient-deficient samples with rich hydrocarbons can increase the rate of cells growth and hydrocarbon degradation. Because nitrate has thermodynamic advantages as TEA, it participates in the assimilation and/or dissimilatory reduction process under oxygen limitation and anaerobic conditions, which promotes the heterotrophic or autotrophic denitrification process and simultaneously oxidizes organic matter (especially alkanes) [130]. At the same time, in the terrestrial underground environment, the phosphorus content is very low. Although some areas contain a lot of apatite, it cannot be used by biology. Several inorganic and organic forms of phosphate have been successfully used to stimulate environmental pollution [131]. Therefore, the addition of nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus contributes to the effective oxidation of carbon substrates and accelerates bacterial growth and hydrocarbon catabolism[88]. At present, the best C:N:P for efficient biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons has been reported as 100:10:1 [132].

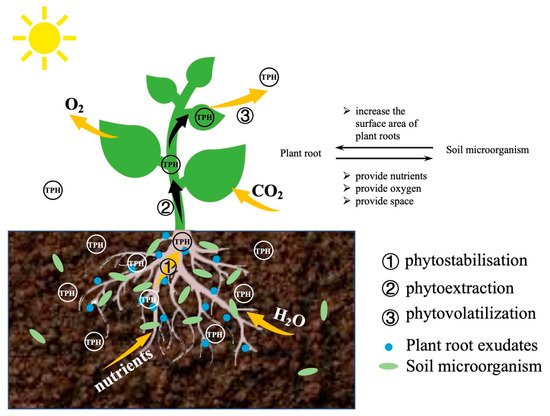

5.3. Microorganism-plant interactions in remediation of hydrocarbons

The microorganism-plant combined method is the most common method for in-situ remediation. Studies have shown that in phytoremediation, organic pollutants are mainly mineralized by plant-related microorganisms. It has also been suggested that the remediation potential of plants depends to some extent on the number of bacteria in their surrounding environment [133].Therefore, in the process of remediation of pollutants, the synergy between plants and microorganisms accelerates the degradation and mineralization of pollutants. Plants and microorganisms have special enzymes and other substances, which can convert many toxic and complex chemical substances into simple and less toxic compounds. This process is conducive to their growth under polluted conditions. Plant rhizosphere can provide nutrients for microorganisms, oxygen and provide space for their attachment and growth [134][135]. These microorganisms increase the surface area of plant roots, allowing the roots to contact the soil and obtain more nutrients necessary for plant growth. Therefore, the inoculated bacteria are more concentrated in the soil around the roots of the vegetation [136]. At the same time, plant root exudates can stimulate the degradation process of microorganisms by changing the composition of the microbial community and improving microbial activity[137].

Figure 6. The general interactions that occur in the microorganism-plant remediation of contaminants.

Studies have shown that plants such as Merr.,Setaria viridis Beauv., Plantago asiatica L., Phragmites communis, Medicago sativa, Festuca elata Keng ex E.Alexeev and Lolium perenne L. are suitable for the climate and environment in China, and these are candidates for phytoremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil in China [138]. After 90 days of repairing petroleum-contaminated soil by Festuca elata Keng ex E.Alexeev, the petroleum removal rate is about 64% [139]. Festuca elata Keng ex E.Alexeev can not only effectively remove benzopyrene from the soil [140], but its growth also promotes soil biological activity in saline-alkali areas with petroleum pollution [52]. Fig. 6 outlines the general interactions that occur in the microorganism-plant remediation of contaminants.

Microorganism-plant remediation mechanism can be divided into the degradation, extraction, inhibition and a combination of three methods. Roots not only provide oxygen to rhizosphere bacteria through respiration, but also promote the secretion of root exudates and the degradation of rhizosphere pollutants [141]. Subsequently, through the expression of special enzymes(such as nitroreductase, dehalogenase, laccase and peroxidase etc.), plants and strains degrade hydrocarbons into simpler organic compounds [142]. Some pollutants are adsorbed on the root surface and accumulate in the root through the hemicellulose of the plant cell wall and the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane [143]. Part of the pollutants are absorbed by phytoextraction/plant transfer to the upper part (stems and leaves) of plants [144]. Finally, some pollutants are released into the atmosphere through phytovolatilization [145]. Due to the self-protection mechanism of plants, some plants restrict the transportation of hydrocarbons from the roots to the ground, so that more hydrocarbons are retained in the root tissues. This restriction protects the chlorophyll and other nutrient synthesis systems of plants and ensures the normal operation of photosynthesis [144]. This is to ensure the normal photosynthesis activities of plants to generate more energy for survival and repair process.

6. Advantages and challenges in combined microbial methods application for hydrocarbon removal

With the exploitation of petroleum, the release of toxic pollutants in the soil environment has increased dramatically. Bioremediation has the characteristics of convenient operation, economic feasibility and no secondary pollution etc., which is currently a research hotspot for remediation of oily soil[64]. The combination of biochar, nutrients and plant with microorganisms not only increases the biological stability and activity of microorganisms, but also improves the ability of microorganisms to degrade petroleum pollutants. Three combined microbial methods have the following advantages. These methods will not damage the soil environment, physical, chemical and biological properties, and even better than the original properties after restoration. In addition, they can degrade organic pollutants into completely harmless inorganic substances (carbon dioxide and water) without secondary pollution problems.

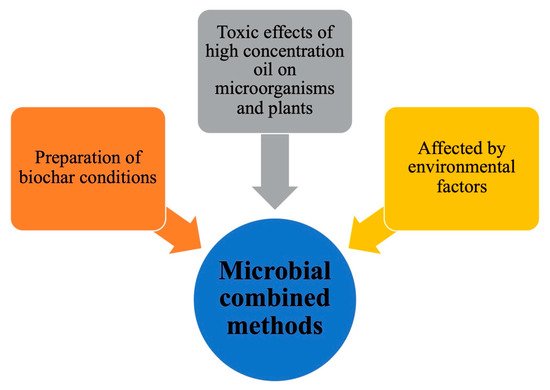

Figure 7. Some challenges of three microbial combined methods.

At present, the three repair methods only stay in the laboratory stage, and there are few strains used in engineering repair. Many influencing factors and degradation mechanisms are not yet clear, so further research is needed. Some challenges of three combined microbial methods are summarized in Fig. 7. The long-term stability and tolerance of biochar is one of the challenges faced by microorganism-biochar combined restoration. The high temperature pyrolysis biochar has a lower H/C ratio, which leads to enhanced electron donor-acceptor interaction, which makes the adsorption efficiency of biochar higher [146]. However, changes in environmental conditions (such as pH) and the abiotic or biodegradation of biochar will promote the desorption of PAH from biochar to sediment.

The ability of strains and plants to metabolize petroleum pollutants is the main challenge for microorganism-nutrients and microorganism -plants combined remediation. Excessive petroleum pollution in contaminated soil will negatively affect the growth and metabolism of microorganisms and plants, and soil environmental factors(temperature, humidity and pH) also affect the ability of microorganisms and plants to metabolize pollutants.

7. Conclusions

This entry outlines the method of remediation of petroleum-contaminated soil by the combined microbial methods. Although a combination of microorganisms-biochar/nutrients/plants can be used to remediate petroleum-contaminated soil to remedy the problems of a single remediation, there is no single method that is most suitable for all types of pollutants and various specific location conditions that occur in the affected environment. Therefore, it is necessary to construct an effective joint remediation technology based on the physical and chemical properties of soil at different contaminated sites and the types of pollutants. And study the migration, distribution, degradation mechanism of pollutants in the combined system, and the interaction and relationship with microorganisms. Select specific remedial measures by clarifying the internal and external factors that affect the restoration. Therefore, constructing a microbial joint remediation technology with a wide range of degradable pollutants, high degradation efficiency, strong stability and eco-friendly is the best choice for the current petroleum-contaminated soil remediation technology.

References

- Abbaspour, A.; Zohrabi, F.; Dorostkar, V.; Faz, A.; Acosta, J.A. Remediation of an oil-contaminated soil by two native plants treated with biochar and mycorrhizae. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 254, 109755.

- Freedman, B. Oil pollution. In Environmental Ecology, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 159–188.

- Suganthi, S.H.; Murshid, S.; Sriram, S. Enhanced biodegradation of hydrocarbons in petroleum tank bottom oil sludge and characterization of biocatalysts and biosurfactants. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 220, 87–95.

- Ansari, N.; Hassanshahian, M.; Ravan, H. Study the microbial communities’ changes in desert and farmland soil after crude oil pollution. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2018, 12, 391–398.

- Ekundayo, E.O.; Emede, T.O.; Osayande, D.I. Effects of crude oil spillage on growth and yield of maize (Zea mays L.) in soils of midwestern Nigeria. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2001, 56, 313–324.

- Kumari, S.; Regar, R.K.; Manickam, N. Improved polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation in a crude oil by individual and a consortium of bacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 254, 174–179.

- Ozigis, M.S.; Kaduk, J.D.; Jarvis, C.H. Detection of oil pollution impacts on vegetation using multifrequency SAR, multispectral images with fuzzy forest and random forest methods. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113360.

- O’Callaghan-Gordo, C.; Orta-Martínez, M.; Kogevinas, M. Health effects of non-occupational exposure to oil extraction. Environ. Health 2016, 15, 1–4.

- Maletić, S.; Dalmacija, B.; Rončević, S. Petroleum hydrocarbon biodegradability in soil–implications for bioremediation. Intech 2013, 43, 43–64.

- Sankaran, S.; Pandey, S.; Sumathy, K. Experimental investigation on waste heat recovery by refinery oil sludge incineration using fluidised-bed technique. Environ. Lett. 1998, 33, 829–845.

- Liao, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, H.; Su, C. Effect of various chemical oxidation reagents on soil indigenous microbial diversity in remediation of soil contaminated by PAHs. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 483–491.

- Giannopoulos, D.; Kolaitis, D.I.; Togkalidou, A.; Skevis, G.; Founti, M.A. Quantification of emissions from the co-incineration of cutting oil emulsions in cement plants—Part II: Trace species. Fuel 2007, 86, 2491–2501.

- Vidonish, J.E.; Zygourakis, K.; Masiello, C.A.; Sabadell, G.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Thermal treatment of hydrocarbon-impacted soils: A Review of technology innovation for sustainable remediation. Engineering 2016, 2, 426–437.

- Kang, C.-U.; Kim, D.-H.; Khan, M.A.; Kumar, R.; Ji, S.-E.; Choi, K.-W.; Paeng, K.-J.; Park, S.; Jeon, B.-H. Pyrolytic remediation of crude oil-contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136498.

- Ku-Fan, C.; Yu-Chen, C.; Wan-Ting, C. Remediation of diesel-contaminated soil using in situ chemical oxidation (ISCO) and the effects of common oxidants on the indigenous microbial community: A comparison study. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 1877–1888.

- Das, N.; Chandran, P. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminants: An overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011, 10, 1–13.

- Senko, J.M.; Campbell, B.S.; Henriksen, J.R.; Elshahed, M.S.; Dewers, T.A.; Krumholz, L.R. Barite deposition resulting from phototrophic sulfide-oxidizing bacterial activity. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2004, 68, 773–780.

- Velacano, M.; Castellanohinojosa, A.; Vivas, A.F.; Toledo, M.V.M. Effect of Heavy Metals on the Growth of Bacteria Isolated from Sewage Sludge Compost Tea. Adv. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 644–655.

- Chaîneau, C.H.; Rougeux, G.; Yéprémian, C.J. Oudot. Effects of nutrient concentration on the biodegradation of crude oil and associated microbial populations in the soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 1490–1497.

- ChaIneau, C.-H.; Morel, J.-L.; Oudot, J. Microbial degradation in soil microcosms of fuel oil hydrocarbons from drilling cuttings. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 29, 1615–1621.

- Pino, N.J.; Muñera, L.M.; Peñuela, G.A. Bioaugmentation with immobilized microorganisms to enhance phytoremediation of PCB-contaminated soil. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2016, 25, 419–430.

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Zhao, J.; Gao, D.-M.; Li, F.-M.; Xing, B. Biodegradation of crude oil in contaminated soils by free and immobilized microorganisms. Pedosphere 2012, 22, 717–725.

- Hamamura, N.; Fukui, M.; Ward, D.M.; Inskeep, W.P. Assessing soil microbial populations responding to crude-oil amendment at different temperatures using phylogenetic, functional gene (alkB) and physiological analyses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 7580–7586.

- Zou, C.; Wang, M.; Xing, Y.; Lan, G.; Ge, T.; Yan, X.; Gu, T. Characterization and optimization of biosurfactants produced by Acinetobacter baylyi ZJ2 isolated from crude oil-contaminated soil sample toward microbial enhanced oil recovery applications. Biochem. Eng. J. 2014, 90, 49–58.

- Das, M.; Adholeya, A. Role of Microorganisms in Remediation of Contaminated Soil. In Microorganisms in Environmental Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012.

- Wu, M.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Ye, X. Effect of bioaugmentation and biostimulation on hydrocarbon degradation and microbial community composition in petroleum-contaminated loessal soil. Chemosphere 2019, 237, 124456.

- Fanaei, F.; Moussavi, G.; Shekoohiyan, S. Enhanced treatment of the oil-contaminated soil using biosurfactant-assisted washing operation combined with H2O2-stimulated biotreatment of the effluent. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110941.

- Abioye, O.P. Biological remediation of hydrocarbon and heavy metals contaminated soil. Soil Contam. 2011, 7, 127–142.

- Adipah, S. Introduction of petroleum hydrocarbons contaminants and its human effects. J. Environ. Sci. Public Health 2018, 3, 001–009.

- Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Norbu, N.; Liu, W. The harm of petroleum-polluted soil and its remediation research. Aip Conf. Proc. 2017, 1864, 020222.

- Kachieng’a, L.; Momba, M.N.B. Kinetics of petroleum oil biodegradation by a consortium of three protozoan isolates (Aspidisca sp., Trachelophyllum sp. and Peranema sp.). Biotechnol. Rep. 2017, 15, 125–131.

- Sarma, H.; Nava, A.R.; Prasad, M.N.V. Mechanistic understanding and future prospect of microbe-enhanced phytoremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2019, 13, 318–330.

- Brakstad, O.G.; Ribicic, D.; Winkler, A.; Netzer, R. Biodegradation of dispersed oil in seawater is not inhibited by a commercial oil spill dispersant. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 555–561.

- Włodarczyk-Makuła, M. Half-Life of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in stored sewage sludge. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2012, 38, 33–44.

- Elumalai, P.; Parthipan, P.; Karthikeyan, O.P.; Rajasekarcorresponding, A. Enzyme-mediated biodegradation of long-chain n-alkanes (C32 and C40) by thermophilic bacteria. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 1–10.

- Aguelmous, A.; Zegzouti, Y.; Khadra, A.; Fels, L.E.; Souabi, S.; Hafidi, M. Landfilling and composting efficiency to reduce genotoxic effect of petroleum sludge. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 20, 101047.

- Schirmer, A.; Rude, M.A.; Li, X.; Popova, E.; Cardayre, S.B.D. Microbial Biosynthesis of Alkanes. Science 2010, 329, 559–562.

- Ryckaert, J.P.; Bellemans, A. Molecular dynamics of liquid alkanes. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 1978, 66, 95–106.

- Zakaria, M.P.; Bong, C.-W.; Vaezzadeh, V. Fingerprinting of petroleum hydrocarbons in malaysia using environmental forensic techniques: A 20-year field data review. In Oil Spill Environmental Forensics Case Studies; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2018; Chapter 16; pp. 345–372.

- Sadeghbeigi, R. Chapter 3—FCC Feed Characterization. In Fluid Catalytic Cracking Handbook, 3rd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2012.

- Tissot, B.P.; Welte, D.H. Composition of crude oils. In Petroleum Formation and Occurrence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; Chapter 1; pp. 333–368.

- Vasconcelos, I.U.; FrançaI, F.P.D.; OliveiraII, F.J.S. Removal of high-molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Química Nova 2011, 34, 218–221.

- Haines, J.R.; Alexander, M. Microbial degradation of high-molecular-weight alkanes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1974, 28, 1084–1085.

- Imam, A.; Suman, S.K.; Ghosh, D.K. Kanaujia, P. Analytical approaches used in monitoring the bioremediation of hydrocarbons in petroleum-contaminated soil and sludge. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 50–64.

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 107–123.

- Fooladi, M.; Moogouei, R.; Jozi, S.A.; Golbabaei, F.; Tajadod, G. Phytoremediation of BTEX from indoor air by Hyrcanian plants. Environ. Health Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 6, 233–240.

- Wei, Z.; Wang, J.J.; Meng, Y.; Li, J.; Gaston, L.A.; Fultz, L.M.; DeLaune, R.D. Potential use of biochar and rhamnolipid biosurfactant for remediation of crude oil-contaminated coastal wetland soil: Ecotoxicity assessment. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126617.

- Gomez-Eyles, J.L.; Collins, C.D.; Hodson, M.E. Using deuterated PAH amendments to validate chemical extraction methods to predict PAH bioavailability in soils. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 918–923.

- Achuba, F.I.; Peretiemo-Clarke, B.O. Effect of spent engine oil on soil catalase and dehydrogenase activities. Int. Agrophys. 2008, 22, 1–4.

- Polyak, Y.; Bakina, L.G.; Bakina, L.G.; Chugunova, M.V.; Bure, V. Effect of remediation strategies on biological activity of oil-contaminated soil—A field study. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 126, 57–68.

- Wei, Y.; Li, G. Effect of oil pollution on water characteristics of loessial soil. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 170, 032154.

- Barua, D.; Buragohain, J.; Sarma, S.K. Certain physico-chemical changes in the soil brought about by contamination of crude oil in two oil fields of Assam. NE India Pelagia Res. Libr. 2011, 1, 154–161.

- Osuji, L.C.; Idung, I.D.; Ojinnaka, C.M. Preliminary investigation on Mgbede-20 oil-polluted site in Niger Delta, Nigeria. Chem. Biodivers. 2006, 3, 568–577.

- Xin, L.; Hui-hui, Z.; Bing-bing, Y.; Nan, X.; Wen-xu, Z.; Ju-wei, H.; Guang-yu, S. Effects of Festuca arundinacea on the microbial community in crude oil-contaminated saline-alkaline soil. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 23, 3414–3420.

- Steliga, T.; Kluk, D. Application of Festuca arundinacea in phytoremediation of soils contaminated with Pb, Ni, Cd and petroleum hydrocarbons. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 194, 110409.

- Mangse, G.; Werner, D.; Meynet, P.; Ogbaga, C.C. Microbial community responses to different volatile petroleum hydrocarbon class mixtures in an aerobic sandy soil. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 114738.

- Uzoho, B.; Oti, N.; Onweremadu, E. Effect of crude oil pollution on maize growth and soil properties in Ihiagwa, Imo State, Nigeria. Int. J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2006, 5, 91–100.

- Lorestani, B.; Kolahchi, N.; Ghasemi, M.; Cheraghi, M.; Yousefi, N. Survey the effect of oil pollution on morphological characteristics in Faba Vulgaris and Vicia Ervilia. J. Chem. Health Risks 2012, 2, 2251–6727.

- Zhen, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.; Song, B.; Wang, Y.; Tang, J. Combination of rhamnolipid and biochar in assisting phytoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminated soil using Spartina anglica. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 85, 107–118.

- Kuppusamy, S.; Raju, M.N.; Mallavarapu, M.; Kadiyala, V. Impact of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons on Human Health. In Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 139–165.

- Haller, H.; Jonsson, A. Growing food in polluted soils: A review of risks and opportunities associated with combined phytoremediation and food production (CPFP). Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126826.

- Hussain, I.; Puschenreiter, M.; Gerhard, S.; Sani, S.G.A.S.; Khan, W.-u.-d.; Reichenauer, T.G. Differentiation between physical and chemical effects of oil presence in freshly spiked soil during rhizoremediation trial. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 18451–18464.

- Tao, K.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Hu, X.; Cao, L.; Yuan, X. Biodegradation of crude oil by a defined co-culture of indigenous bacterial consortium and exogenous Bacillus subtilis. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 224, 327–332.

- Abena, M.T.B.; Li, T.; Shah, M.N.; Zhong, W. Biodegradation of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) in highly contaminated soils by natural attenuation and bioaugmentation. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 864–874.

- Bacosa, H.P.; Suto, K.; Inoue, C. Bacterial community dynamics during the preferential degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons by a microbial consortium. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 74, 109–115.

- Lee, D.W.; Lee, H.; Kwon, B.-O.; Khim, J.S.; Yim, U.H.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, J.-J. Biosurfactant-assisted bioremediation of crude oil by indigenous bacteria isolated from Taean beach sediment. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 254–264.

- Wang, B.; Teng, Y.; Yao, H.; Christie, P. Detection of functional microorganisms in benzene [a] pyrene-contaminated soils using DNA-SIP technology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124788.

- Pi, Y.; Chen, B.; Bao, M.; Fan, F.; Cai, Q.; Ze, L.; Zhang, B. Microbial degradation of four crude oil by biosurfactant producing strain Rhodococcus sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 232, 263–269.

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Kong, D.; Liu, X.; Shen, S. Synergistic degradation of crude oil by indigenous bacterial consortium and T exogenous fungus Scedosporium boydii. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 264, 190–197.

- Varjani, S.J.; Upasani, V.N. Biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons by oleophilic strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5514. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 222, 195–201.

- Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Lai, Q.; Shao, Z. Gene diversity of CYP153A and AlkB alkane hydroxylases in oil-degrading bacteria isolated from the Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 1230–1242.

- Cao, B.; Nagarajan, K.; Loh, K.C. Biodegradation of aromatic compounds: Current status and opportunities for biomolecular approaches. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 85, 207–228.

- Margesin, R.; Zimmerbauer, A.; Schinner, F. Soil lipase activity–A useful indicator of oil biodegradation. Biotechnol. Tech. 1999, 13, 859–863.

- Sirajuddin, S.; Rosenzweig, A.C. Enzymatic Oxidation of Methane. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 2283–2294.

- Liu, Y.-C.; Li, L.-Z.; Wu, Y.; Tian, W.; Zhang, L.-P.; Xu, L.; Shen, Q.-R.; Shen, B. Isolation of an alkane-degrading Alcanivorax sp. strain 2B5 and cloning of the alkB gene. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 310–316.

- Huan, L.; Jing, X.; Rubing, L.; Jianhua, L.; ONE, D.A.J.P. Characterization of the Medium- and Long-Chain n-Alkanes Degrading Pseudomonas aeruginosa Strain SJTD-1 and Its Alkane Hydroxylase Genes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105506.

- Liu, J.; Zhao, B.; Lan, Y.; Ma, T. Enhanced degradation of different crude oils by defined engineered consortia of Acinetobacter venetianus RAG-1 mutants based on their alkane metabolism. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 327, 124787.

- Mimmi, T.-H.; Alexander, W.; Trond, E.E.; Hans-Kristian, K.; Sergey, B.Z. Identification of novel genes involved in long-chain n-alkane degradation by Acinetobacter sp. strain DSM 17874. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 3327–3332.

- Abouseoud, M.; Yataghene, A.; Amrane, A.; Maachi, R. Biosurfactant production by free and alginate entrapped cells of Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 35, 1303–1308.

- Hesham, E.L.; Mawad, A.M.M.; Mostafa, Y.M.; Shoreit, A.J.M. Study of enhancement and inhibition phenomena and genes relating to degradation of petroleum polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in isolated bacteria. Microbiology 2014, 83, 599–607.

- Varjani, S.J. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 223, 277–286.

- Champion, P.M.; Gunsalus, I.C.; Wagner, G.C. Resonance Raman investigations of cytochrome P450CAM from Pseudomonas putida. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 3743–3751.

- Noble, M.E.M.; Cleasby, A.; Johnson, L.N.; Egmond, M.R.; Frenken, L.G.J. The crystal structure of triacylglycerol lipase from Pseudomonas glumae reveals a partially redundant catalytic aspartate. FEBS Lett. 1993, 331, 123–128.

- Rojo, F. Degradation of alkanes by bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 2477–2490.

- Xia, Y.; Min, H.; Rao, G.; Lv, Z.; Liu, J.; Ye, Y.; Duan, X. Isolation and character- ization of phenanthrene-degrading Sphingomonas paucimobilis strain ZX4. Biodegradation 2005, 16, 393–402.

- Oyetibo, G.O.; Chien, M.F.; Ikeda-Ohtsubo, W.; Suzuki, H.; Obayori, O.S.; Adebusoye, S.A.; Ilori, M.O.; Amund, O.O.; Endo, G. Biodegradation of crude oil and phenanthrene by heavy metal resistant Bacillus subtilis isolated from a multi-polluted industrial wastewater creek. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 120, 143–151.

- Deng, M.-C.; Li, J.; Liang, F.-R.; Wang, J.-H. Isolation and characterization of a novel hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium Achromobacter sp HZ01 from the crude oil-contaminated seawater at the Daya Bay, southern China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 83, 79–86.

- Lily, M.K.; Bahuguna, A.; Dangwal, K.; Garg, V. Degradation of Benzo [a] Pyrene by a novel strain Bacillus subtilis BMT4i (MTCC 9447). Braz. J. Microbiol. 2009, 40, 884–892.

- Al-Thukair, A.A.; Malik, K. Pyrene metabolism by the novel bacterial strains Burkholderia fungorum (T3A13001) and Caulobacter sp (T2A12002) isolated from an oil-polluted site in the Arabian Gulf. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 110, 32–37.

- Darma, U.Z.; Aziz, N.A.A.; Zulkefli, S.Z.; Mustafa, M. Identification of Phenanthrene and Pyrene degrading bacteria from used engine oil contaminated soil. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2016, 7, 680–686.

- Rajkumari, J.; Singha, L.P.; Pandey, P. Genomic insights of aromatic hydrocarbon degrading Klebsiella pneumoniae AWD5 with plant growth promoting attributes: A paradigm of soil isolate with elements of biodegradation. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 1–22.

- Heitkamp, M.A.; Freeman, J.P.; Miller, D.W.; Cerniglia, C.E. Pyrene degradation by a Mycobacterium sp.: Identification of ring oxidation and ring fission products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 2556–2565.

- Ping, L.; Guo, Q.; Chen, X.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, H. Biodegradation of pyrene and benzo[a]pyrene in the liquid matrix and soil by a newly identified Raoultella planticola strain. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 56.

- Song, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Hu, Z. Isolation, characterization of Rhodococcus sp. P14 capable of degrading high-molecular-weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and aliphatic hydrocarbons. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2122–2128.

- Liu, Y.; Hu, H.; Zanaroli, G.; Xu, P.; Tang, H. A Pseudomonas sp. strain uniquely degrades PAHs and heterocyclic derivatives via lateral dioxygenation pathways. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123956.

- Patel, V.; Cheturvedula, S.; Madamwar, D. Phenanthrene degradation by Pseudoxanthomonas sp. DMVP2 isolated from hydrocarbon contaminated sediment of Amlakhadi canal, Gujarat, India. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 201, 43–51.

- Chen, J.; Wong, M.H.; Wong, Y.S.; Tam, N.F.Y. Multi-factors on biodegradation kinetics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) by Sphingomonas sp. a bacterial strain isolated from mangrove sediment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2008, 57, 695–702.

- Tiwari, B.; Manickam, N.; Kumari, S.; Tiwari, A. Biodegradation and dissolution of polyaromatic hydrocarbons by Stenotrophomonas sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 216, 1102–1105.

- Balachandran, C.; Duraipandiyan, V.; Balakrishna, K.; Ignacimuthu, S. Petroleum and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) degradation and naphthalene metabolism in Streptomyces sp. (ERI-CPDA-1) isolated from oil contaminated soil. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 112, 83–90.

- Al-Hawash, A.B.; Zhang, X.; Ma, F. Removal and biodegradation of different petroleum hydrocarbons using the filamentous fungus Aspergillus sp. RFC-1. Microbiologyopen 2019, 8, e00619.

- Baek, K.-H.; Yoon, B.-D.; Oh, H.-M.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, I.-S. Biodegradation of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons by Nocardia sp. H17-1. Geomicrobiol. J. 2007, 23, 253–259.

- Govarthanan, M.; Fuzisawa, S.; Hosogai, T.; Chang, Y.-C. Biodegradation of aliphatic and aromatichydrocarbons using the filamentous fungusPenicillium sp. CHY-2 and characterization of itsmanganese peroxidase activity. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 20716–20723.

- Wang, X.; Gong, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X. Degradation of pyrene and benzo(a)pyrene in contaminated soil by immobilized fungi. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2008, 25, 677–684.

- Liu, Y.; Han, H.; Fang, F. Degradation of long-chain n-alkanes by Acinetobacter sp. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 726–731, 2151–2155.

- Wang, D.; Lin, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons by bacillus subtilis BL-27, a strain with weak hydrophobicity. Molecules 2019, 24, 3021.

- Whyte, L.G.; Hawari, J.; Zhou, E.; Bourbonnière, L.; Inniss, W.E.; Greer, C.W. Biodegradation of Variable-Chain-Length Alkanes at Low Temperatures by a Psychrotrophic Rhodococcussp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2578–2584.

- Teh, J.S.; Lee, K.H. Utilization of n-Alkanes by Cladosporium resinae. Appl. Microbiol. 1973, 25, 454–457.

- Quatrini, P.; Scaglione, G.; Pasquale, C.D.; Riela, S.; Puglia, A.M. Isolation of Gram-positive n-alkane degraders from a hydrocarbon-contaminated Mediterranean shoreline. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 104, 251–259.

- Chiciudean, I.; Nie, Y.; Tănase, A.-M.; Stoica, I.; Wu, X.-L. Complete genome sequence of Tsukamurella sp. MH1: A wide-chain length alkane-degrading actinomycete. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 268, 1–5.

- Atlas, R.M. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons: An environmental perspective. Microbiol. Rev. 1981, 45, 180–209.

- Chen, Y.-A.; Liu, P.-W.G.; Whang, L.-M.; Wu, Y.-J.; Cheng, S.-S. Effect of soil organic matter on petroleum hydrocarbon degradation in diesel/fuel oil-contaminated soil. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 129, 603–612.

- Zhang, H.; Hu, Z.; Hou, S.; Xu, T. Effects of microbial degradation on morphology, chemical compositions and microstructures of bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 248, 118569.

- Hajieghrari, M.; Hejazi, P. Enhanced biodegradation of n-Hexadecane in solid-phase of soil by employing immobilized Pseudomonas Aeruginosa on size-optimized coconut fibers. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 122134.

- Premnath, N.; Mohanrasu, K.; Rao, R.G.R.; Dinesh, G.H.; Prakash, G.S.; Ananthi, V.; Ponnuchamy, K.; Muthusamy, G.; Arun, A. A crucial review on polycyclic aromatic Hydrocarbons–Environmental occurrence and strategies for microbial degradation. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130608.

- Heitkamp, M.A.; Cerniglia, C.E. Effects of chemical structure and exposure on the microbial degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in freshwater and estuarine ecosystems. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1987, 6, 535–546.

- Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Wen, D.; Fu, R.; Feng, L. Application of alkyl polyglycosides for enhanced bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil using Sphingomonas changbaiensis and Pseudomonas stutzeri. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 719, 137456.

- Lladó, S.; Solanas, A.M.; Lapuente, J.D.; Borràs, M.; Viñas, M. A diversified approach to evaluate biostimulation and bioaugmentation strategies for heavy-oil-contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 435, 262–269.

- Mukome, F.N.D.; Buelowa, M.C.; Shang, u.; Peng, J.; Rodriguez, M.; Mackay, D.M.; Pignatello, J.J.; Sihota, N.; Hoelen, T.P.; Parikh, S.J. Biochar amendment as a remediation strategy for surface soils impacted by crude oil. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 115006.

- Dong, Z.-Y.; Huang, W.-H.; Xing, D.-F.; Zhang, H.-F. Remediation of soil co-contaminated with petroleum and heavy metals by the integration of electrokinetics and biostimulation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 399–408.

- Tahseen, R.; Afzal, M.; Iqbal, S.; Shabir, G.; Khan, Q.M.; Khalid, Z.M.; Banat, I.M. Rhamnolipids and nutrients boost remediation of crude oil-contaminated soil by enhancing bacterial colonization and metabolic activities. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 115, 192–198.

- Qin, G.; Gong, D.; Fan, M.-Y. Bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil by biostimulation amended with biochar. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 85, 150–155.

- Zhao, L.; Deng, J.; Hou, H.; Li, J.; Yang, Y. Investigation of PAH and oil degradation along with electricity generation in soil using an enhanced plant-microbial fuel cell. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 678–683.

- Rhykerd, R.L.; Crews, B.; Mclnnes, K.J.; Weaver, R.W. Impact of bulking agents, forced aeration, and tillage on remediation of oil-contaminated soil. Bioresour. Technol. 1999, 67, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dai, D.; Li, G. Porous biocarrier-enhanced biodegradation of crude oil contaminated soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2009, 63, 80–87. Rhykerd, R.L.; Crews, B.; Mclnnes, K.J.; Weaver, R.W. Impact of bulking agents, forced aeration, and tillage on remediation of oil-contaminated soil. Bioresour. Technol. 1999, 67, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dai, D.; Li, G. Porous biocarrier-enhanced biodegradation of crude oil contaminated soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2009, 63, 80–87. Rhykerd, R.L.; Crews, B.; Mclnnes, K.J.; Weaver, R.W. Impact of bulking agents, forced aeration, and tillage on remediation of oil-contaminated soil. Bioresour. Technol. 1999, 67, 279–285.

- Xu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, P.; Xu, L. Oil-addicted biodegradation of macro-alkanes in soils with activator. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 159, 107578.

- Tang, J.; Wang, R.; Niu, X.; Zhou, Q. Enhancement of soil petroleum remediation by using a combination of ryegrass (Lolium perenne) and different microorganisms. Soil Tillage Res. 2010, 110, 87–93.

- Shahzad, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Bano, A.; Sattar, S.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Qin, M.; Shakoor, A. Hydrocarbon degradation in oily sludge by bacterial consortium assisted with alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and maize (Zea mays L.). Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 1–12.

- Yateem, A.; Balba, M.T.; El-Nawawy, A.S.; Al-Awadhi, N. Plants-associated microflora and the remediation of oil-contaminated soil. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2008, 2, 183–191.

- Jørgensen, K.S.; Puustinen, J.; Suortti, A.-M. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil by composting in biopiles. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 107, 245–254.

- Xu, Y.; Lu, M. Bioremediation of crude oil-contaminated soil: Comparison of different biostimulation and bioaugmentation treatments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 183, 395–401.

- Joo, H.-S.; Ndegwa, P.M.; Shoda, M.; Phae, C.-G. Bioremediation of oil-contaminated soil using Candida catenulata and food waste. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 156, 891–896.

- Schaefer, M.; Petersen, S.O.; Filser, J. Effects of Lumbricus terrestris, Allolobophora chlorotica and Eisenia fetida on microbial community dynamics in oil-contaminated soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 2065–2076.

- Luo, C.; Lü, F.; Shao, L.; He, P. Application of eco-compatible biochar in anaerobic digestion to relieve acid stress and promote the selective colonization of functional microbes. Water Res. 2014, 70, 710–718.

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil by petroleum-degrading bacteria immobilized on biochar. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 35304–35311.

- Margesin, R.; Schinner, F. Bioremediation (natural attenuation and biostimulation) of diesel-oil-contaminated soil in an alpine glacier skiing area. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 3127–3133.

- Kanissery, R.G.; Sims, G.K. Biostimulation for the enhanced degradation of herbicides in soil. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2011, 2011, 988–1027.

- Hazen, T.C. Bioremediation. In Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010.

- Sun, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Hu, X. Nutrient depletion is the main limiting factor in the crude oil bioaugmentation process. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 100, 317–327.

- Sarkar, J.; Kazy, S.K.; Gupta, A.; Dutta, A.; Mohapatra, B.; Roy, A.; Bera, P.; Mitra, A.; Sar, P. Biostimulation of Indigenous Microbial Community for Bioremediation of Petroleum Refinery Sludge. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1407.

- Bento, F.M.; Camargo, F.A.O.; Okeke, B.C.; Frankenberger, W.T. Comparative bioremediation of soils contaminated with diesel oil by natural attenuation, biostimulation and bioaugmentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96, 1049–1055.

- Varjani, S.; Upasani, V.N. Influence of abiotic factors, natural attenuation, bioaugmentation and nutrient supplementation on bioremediation of petroleum crude contaminated agricultural soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 245, 358–366.

- Rehman, K.; Imran, A.; Amin, I.; Afzal, M. Inoculation with bacteria in floating treatment wetlands positively modulates the phytoremediation of oil field wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 349, 242–251.

- Weyens, N.; Lelie, D.V.D.; Taghavi, S.; Newman, L.; Vangronsveld, J. Exploiting plant–microbe partnerships to improve biomass production and remediation. Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 591–598.

- Muhammad, A.; Sohail, Y.; Thomas, G.R.; Angela, S. The inoculation method affects colonization and performance of bacterial inoculant strains in the phytoremediation of soil contaminated with diesel oil. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2018, 14, 35–47.

- Shehzadi, M.; Afzal, M.; Khan, M.U.; Islam, E.; Mobin, A.; Anwar, S.; Khan, Q.M. Enhanced degradation of textile effluent in constructed wetland system using Typha domingensis and textile effluent-degrading endophytic bacteria. Water Res. 2014, 58, 152–159.