| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rob Barlow | + 2044 word(s) | 2044 | 2021-09-24 10:24:48 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 576 word(s) | 2620 | 2021-09-28 08:17:10 | | |

Video Upload Options

Phygital consumer experiences provide marketers an opportunity to combine and leverage the benefits of in-person shopping with digital payment in ways that are already transforming the modern retail shopping environment.

1. Introduction

The concept of “phygital” consumption experiences is relatively new, reflecting the novelty of the emerging digital technologies that empower them [1][2]. Phygital marketing involves crafting a consumer journey that integrates physical and digital experiences in a seamless way, creating experiences that are only possible due to the rise of emerging digital technologies [3]. For example, popular phygital approaches involve incorporating contactless payment systems, interactive touch screens, seamless digital payment systems, and augmented reality into the customer experience [4][5]. Ultimately, the use of such strategies has a wide application across industries (e.g., education, tourism, banking, etc.), but we focus exclusively on retail applications here.

There is significant excitement about the proliferation of phygital marketing in the future of retail commerce [6][7]. While research on the subject is still nascent, early work has found that phygital experiences can be designed to provide a novel and seamless experience that users enjoy, influencing customer perceptions of product value while generating trust and minimizing confusion [8]. In this paper, we review relevant findings from the literatures on retail consumer purchasing behavior, including work on the underlying psychology and neuroscience that helps to explain it, in order to better understand the role that technological innovations, including digital sensing technologies and the rise of augmented and virtual reality, can play in compensating for challenges that arise out of the digital purchasing environment. Presumably, these technologies hold potential to combine many appealing features of the “in person” purchasing experience with the ease of digital search and payment, an exciting and increasingly common combination that has recently been referred to as a “phygital revolution” [9].

Implicit in the excitement about phygital marketing is that physical experiences provide unique value above and beyond what can be offered via digital means. However, the specific sources of this marketing potential remain undertheorized, and the factors determining the appropriateness of such strategies from the standpoint of their capacity to increase sales and net ROI remain unclear. In this paper, we review relevant theoretical models and research findings in consumer psychology and consumer neuroscience with direct application to these issues. Grounded by this literature, we develop a theoretical framework to help explain the potential power of phygital marketing experiences, accounting for their unique value. In doing so, our overarching goal is to equip academics and practitioners with a scientific and practically useful understanding of the dimensions contributing to the potential value of such approaches when integrated as part of a company’s retail marketing strategies. Based on the findings of our review, we develop an account isolating two elements of the consumer experience as particularly important factors contributing to phygital marketing’s power: the pre-purchase product experience and the payment experience. Specifically, we argue that these dimensions comprise a primary source of phygital marketing’s contribution to mental gain and loss calculations dictating retail consumers’ purchasing decisions. We conclude by outlining a more general set of criteria contributing to these calculations, based on the extensive review of relevant literatures, and pose further questions for direct empirical testing and research.

2. Phygital Ideal Types

3. The Psychology and Neuroscience of Purchasing Behavior

3.1. Product Experiences

3.2. Payment Experience

3.3. The Phygital Advantage

4. Additional Dimensions of Phygital Impact: A General Framework

4.1. Anticipated Costs (“Pain of Paying”)

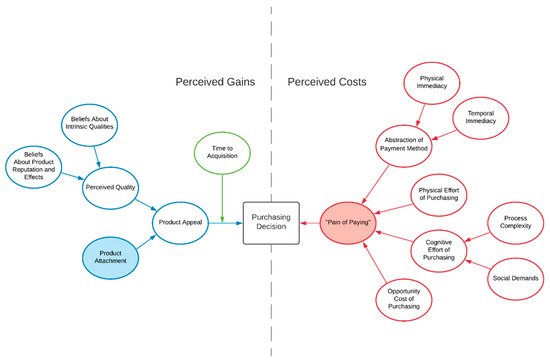

We begin with a more fine-grained analysis of the elements contributing to consumer calculations regarding the anticipated costs of buying goods and of phygital’s potential impact on them, when applicable. As we have seen, these costs are described in terms of the “pain of paying” within dominant psychology and neuroscience literatures on consumer behavior. Existing research suggests that four main elements (captured on the right hand side of Figure 1) contribute to such calculations, each of which may be comprised of multiple dimensions: abstraction of payment method, physical effort of purchasing, cognitive effort of purchasing, and opportunity cost of purchasing. A description of each dimension along with lists of potential measurement variables, key questions, and relevant resources are provided in Table 1.

| Dimension | Description | Measurement Variables | Key Questions | Related Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abstraction of payment method | Does the purchase take place through a direct exchange of currency for goods, or are there vehicles for indirect transacting involved? | Physical immediacy (e.g., cash vs. debit payment) | How does the physical means of transacting affect purchase likelihood and associated brain function? | [19][20][21] |

| Temporal immediacy (e.g., immediate cash/debit vs. credit/financing payment; paying in advance vs. paying upon receipt of good or service) | How does the temporal separation of purchase and payment (i.e., the degree of “coupling”) during the process of transaction affect purchase likelihood and associated brain function? | [22][23][24][21][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33] | ||

| Opportunity cost of purchasing | The amount of time it takes to complete a purchase (e.g., do customers have to wait in a real or virtual line?) | Average time to completion of purchase | How does the real or anticipated amount of time it will take to complete an initial purchase affect purchase likelihood and associated brain function? | [34][32][35][36][37][38] |

| Physical effort of purchasing | The degree of physical “strain” required to complete the purchase (e.g., does it take physical exertion to search for products or present them for purchase?) | Time spent engaging in physical vs. virtual product search, extent of physical labor involved in act of purchasing | How does the real or anticipated amount of physical effort it will take to complete a purchase affect purchase likelihood and associated brain function? | [33][39][35][40] |

| Cognitive effort of purchasing | The degree of cognitive “strain” required to complete the purchase | Process complexity | How does the complication and complexity of the purchasing process affect purchase likelihood and associated brain function? | [6][41][32] |

| Social demands | How does the amount of social interaction involved in the purchasing process affect purchase likelihood and associated brain function? | [6][42][43][44] |

4.2. Anticipated Gains

| Dimension | Description | Measurement Variables | Key Questions | Related Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product appeal (perceived quality) | Consumer beliefs about a product’s level of quality | Consumer beliefs about a product’s intrinsic qualities (e.g., “intrinsic quality” dimensions might include perceived attractiveness, durability, functionality, etc.) | When, for whom, for what types of products, and to what extent do consumer beliefs about a product’s “intrinsic qualities” affect purchase likelihood? | [45][46][47][48][49][50][51] |

| Consumer beliefs about product reputation and associated effects (e.g., what do others think about the product and what will owning the product lead others to think about me? | When, for whom, for what types of products, and to what extent do consumer beliefs about product and/or brand reputation affect purchase likelihood? | [49][50][51] | ||

| Product appeal (product attachment) | The extent to which a given means of showcasing the product provides consumers with experiences that generate product attachment or a sense of “psychological ownership” | Consumer attachment levels as evidenced by, e.g., self-report, willingness to exchange for a product of equal perceived quality, increased valuation relative to pre-exposure levels | For a given level of perceived product quality, how (if at all) do different types of pre-purchase “exposure” to the product (e.g., image vs. video vs. AR/VR interaction vs. first-person use) affect product attachment and purchase likelihood? How are these effects mediated by product and customer type and/or time to acquisition? | [17][52][32][53][54][55] |

| Time to acquisition | The length of time a customer must wait between completing the transaction and receiving the good or service | Consumer beliefs about time to product acquisition after completion of initial transaction | How does the anticipated time to product acquisition affect purchase likelihood? How are these effects mediated by product and customer type? | [56][57][58] |

References

- Cabigiosu, A. Digitalization in the Luxury Fashion Industry; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020.

- Shi, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q. Conceptualization of omnichannel customer experience and its impact on shopping intention: A mixed-method approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 325–336.

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Sprott, D.E.; Andreassen, T.W.; Costley, C.; Klaus, P.; Kuppelwieser, V.; Karahasanovic, A.; Taguchi, T.; Islam, J.U.; Rather, R.A. Customer engagement in evolving technological environments: Synopsis and guiding propositions. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2018–2023.

- Nofal, E.; Reffat, M.; Vande Moere, A. Phygital heritage: An approach for heritage communication. Immersive Learn. In Immersive Learning Research Network; Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 2017; pp. 220–229.

- Moravcikova, D.; Kliestikova, J. Brand Building with Using Phygital Marketing Communication. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2017, 5, 148–153.

- Riegger, A.-S.; Klein, J.F.; Merfeld, K.; Henkel, S. Technology-enabled personalization in retail stores: Understanding drivers and barriers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 140–155.

- Batat, W. Experiential Marketing: Consumer Behavior, Customer Experience and the 7Es; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Purcărea, T. Modern Marketing, CX, CRM, Customer Trust and Identity 2019. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/hmm/journl/v9y2019i1p42-55.html (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Belghiti, S.; Ochs, A.; Lemoine, J.-F.; Badot, O. The Phygital Shopping Experience: An Attempt at Conceptualization and Empirical Investigation; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 61–74.

- Kestenbaum, R. The Impact of 3000 Amazon Go Stores Will Be Massive. Forbes 2018. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/richardkestenbaum/2018/09/23/3000-amazon-go-stores-ibm-cisco-ncr-fujitsu-toshiba-oracle/?sh=73d942585147#2cd9567c5147’ (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- CB Insights. Beyond Amazon Go: The Technologies and Players Shaping Cashier-Less Retail. CB Insights 2018. Available online: https://www.cbinsights.com/research/cashierless-retail-technologies-companies-trends/ (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Papagiannis, H. How AR is Redefining Retail in the Pandemic. Harvard Bus Rev Digit Artic 2020. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/10/how-ar-is-redefining-retail-in-the-pandemic (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- NielsenI, Q. Augmented retail: The New Consumer Reality. 2019. Available online: https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/analysis/2019/augmented-retail-the-new-consumer-reality-2/ (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Hackl, C.; Wolfe, S.G. Marketing New Realities: An Introduction to Virtual Reality & Augmented Reality Marketing, Branding, & Communications; Meraki Press: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2017.

- Raheem, A.R.; Vishnu, P.A.R.M.A.R.; Ahmed, A.M. Impact of product packaging on consumer’s buying behavior. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 122, 125–134.

- Dawar, N.; Parker, P. Marketing universals: Consumers’ use of brand name, price, physical appearance, and retailer reputation as signals of product quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 81–95.

- Knutson, B.; Rick, S.; Wimmer, G.E.; Prelec, D.; Loewenstein, G. Neural Predictors of Purchases. Neuron 2007, 53, 147–156.

- Jai, T.-M.C.; Fang, D.; Bao, F.S.; James, R.N., III; Chen, T.; Cai, W. Seeing It Is Like Touching It: Unraveling the Effective Product Presentations on Online Apparel Purchase Decisions and Brain Activity (An fMRI Study). J. Interact. Mark. 2021, 53, 66–79.

- Runnemark, E.; Hedman, J.; Xiao, X. Do consumers pay more using debit cards than cash? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 285–291.

- Soetevent, A.R. Payment Choice, Image Motivation and Contributions to Charity: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Am. Econ. Journal: Econ. Policy 2011, 3, 180–205.

- Soman, D. Effects of Payment Mechanism on Spending Behavior: The Role of Rehearsal and Immediacy of Payments. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 27, 460–474.

- Hafalir, E.I.; Loewenstein, G.F. The impact of credit cards on spending: A field experiment. SSRN Electron. J. 2011, 1–29.

- Prelec, D.; Simester, D. Always Leave Home Without It: A Further Investigation of the Credit-Card Effect on Willingness to Pay. Mark. Lett. 2001, 12, 5–12.

- Prelec, D.; Loewenstein, G. The Red and the Black: Mental Accounting of Savings and Debt. Mark. Sci. 1998, 17, 4–28.

- Thaler, R. Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsistency. Econ. Lett. 1981, 8, 201–207.

- Loewenstein, G. Anticipation and the Valuation of Delayed Consumption. Econ. J. 1987, 97, 666–684.

- Redelmeier, N.A.; Heller, D.N. Time Preference in Medical Decision Making and Cost—Effectiveness Analysis. Med. Decis. Mak. 1993, 13, 212–217.

- Benzion, U.; Rapoport, A.; Yagil, J. Discount Rates Inferred from Decisions: An Experimental Study. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 270–284.

- Green, L.; Fristoe, N.; Myerson, J. Temporal discounting and preference reversals in choice between delayed outcomes. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 1994, 1, 383–389.

- Green, L.; Fry, A.F.; Myerson, J. Discounting of Delayed Rewards: A Life-Span Comparison. Psychol. Sci. 1994, 5, 33–36.

- Ingene, C.A. Productivity and functional shifting in spatial retailing-private and social perspectives. J. Retail. 1984, 60, 15–36.

- Gupta, A.; Su, B.-C.; Walter, Z. An Empirical Study of Consumer Switching from Traditional to Electronic Channels: A Purchase-Decision Process Perspective. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2004, 8, 131–161.

- Burke, R.R. Technology and the Customer Interface: What Consumers Want in the Physical and Virtual Store. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 411–432.

- Granzin, K.L.; Painter, J.J.; Valentin, E. Consumer logistics as a basis for segmenting retail markets: An exploratory inquiry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 1997, 4, 99–107.

- Knutson, B.; Wimmer, G.E.; Rick, S.; Hollon, N.G.; Prelec, D.; Loewenstein, G. Neural Antecedents of the Endowment Effect. Neuron 2008, 58, 814–822.

- Fenech, T.; O’Cass, A. Internet users’ adoption of Web retailing: User and product dimensions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2001, 10, 361–381.

- Choudhary, A.S. Investigation of Consumers Waiting in Line at a Fashion Store. BEST Int. J. Humanit. Arts Med. Sci. 2016, 4, 83–88.

- Kirby, K.N. Bidding on the future: Evidence against normative discounting of delayed rewards. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1997, 126, 54–70.

- Meuter, M.L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Roundtree, R.I.; Bitner, M.J. Self-Service Technologies: Understanding Customer Satisfaction with Technology-Based Service Encounters. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 50–64.

- Meuter, M.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Brown, S.W. Choosing among Alternative Service Delivery Modes: An Investigation of Customer Trial of Self-Service Technologies. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 61–83.

- Hafner, R.J.; White, M.P.; Handley, S.J. Spoilt for choice: The role of counterfactual thinking in the excess choice and reversibility paradoxes. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 28–36.

- Frederick, S.; Loewenstein, G.; O’Donoghue, T. Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Time Decis. Econ. Psychol. Perspect Intertemporal Choice 2003, 40, 13–86.

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656.

- Wedel, M.; Bigné, E.; Zhang, J. Virtual and augmented reality: Advancing research in consumer marketing. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 443–465.

- Sun, J.J.; Bellezza, S.; Paharia, N. Buy Less, Buy Luxury: Understanding and Overcoming Product Durability Neglect for Sustainable Consumption. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 28–43.

- Handfield, R.; Ghosh, S.; Fawcett, S. Quality-Driven Change and its Effects on Financial Performance. Qual. Manag. J. 1998, 5, 13–30.

- Garvin, D.A. Product quality: An important strategic weapon. Bus. Horizons 1984, 27, 40–43.

- Jacobson, R.; Aaker, D.A. The Strategic Role of Product Quality. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 31.

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J.; Louviere, J. The impact of brand credibility on consumer price sensitivity. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2002, 19, 1–19.

- Teller, C.; Reutterer, T.; Schnedlitz, P. Hedonic and utilitarian shopper types in evolved and created retail agglomerations. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2008, 18, 283–309.

- Rindova, V.P.; Williamson, I.; Petkova, A.P.; Sever, J.M. Being Good or Being Known: An Empirical Examination of the Dimensions, Antecedents, and Consequences of Organizational Reputation. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 1033–1049.

- Peck, J.; Shu, S.B. The Effect of Mere Touch on Perceived Ownership. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 434–447.

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011.

- Kahneman, D.; Knetsch, J.L.; Thaler, R.H. Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem. J. Politi-Econ. 1990, 98, 1325–1348.

- Novemsky, N.; Kahneman, D. The Boundaries of Loss Aversion. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 119–128.

- Ma, S. Fast or free shipping options in online and Omni-channel retail? The mediating role of uncertainty on satisfaction and purchase intentions. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 1099–1122.

- Cao, Y.; Ajjan, H.; Hong, P. Post-purchase shipping and customer service experiences in online shopping and their impact on customer satisfaction: An empirical study with comparison. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 400–416.

- Huang, W.-H.; Shen, G.C.; Liang, C.-L. The effect of threshold free shipping policies on online shoppers’ willingness to pay for shipping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 105–112.