| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Francesco Saverio Robustelli della Cuna | + 2632 word(s) | 2632 | 2021-09-16 08:39:10 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | + 3 word(s) | 2635 | 2021-09-22 05:18:46 | | | | |

| 3 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 2635 | 2021-09-22 05:19:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

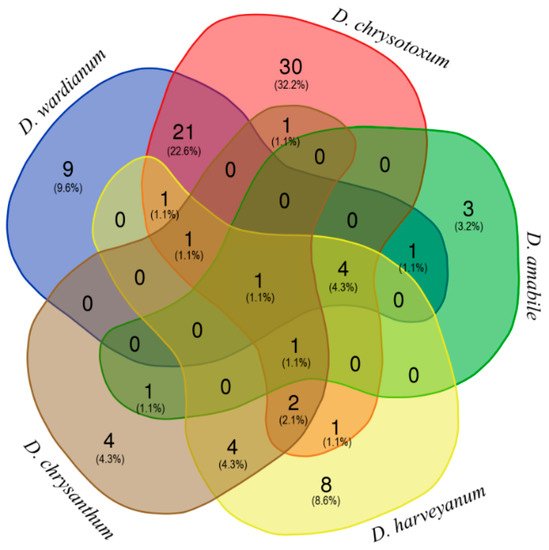

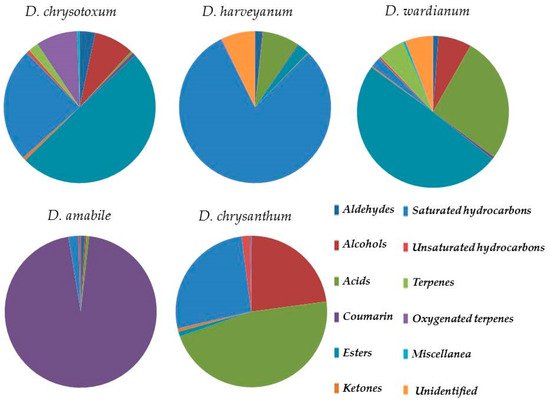

A detailed chemical composition of Dendrobium essential oil has been only reported for a few main species. This article is the first to evaluate the essential oil composition, obtained by steam distillation, of five Indian Dendrobium species: Dendrobium chrysotoxum Lindl., Dendrobium harveyanum Rchb.f., and Dendrobium wardianum R.Warner (section Dendrobium), Dendrobium amabile (Lour.) O’Brien, and Dendrobium chrysanthum Wall. ex Lindl. (section Densiflora). We investigate fresh flower essential oil obtained by steam distillation, by GC/FID and GC/MS. Several compounds are identified, with a peculiar distribution in the species: Saturated hydrocarbons (range 2.19–80.20%), organic acids (range 0.45–46.80%), esters (range 1.03–49.33%), and alcohols (range 0.12–22.81%). Organic acids are detected in higher concentrations in D. chrysantum, D. wardianum, and D. harveyanum (46.80%, 26.89%, and 7.84%, respectively). This class is represented by palmitic acid (13.52%, 5.76, and 7.52%) linoleic acid (D. wardianum 17.54%), and (Z)-11-hexadecenoic acid (D. chrysantum 29.22%). Esters are detected especially in species from section Dendrobium, with ethyl linolenate, methyl linoleate, ethyl oleate, and ethyl palmitate as the most abundant compounds. Alcohols are present in higher concentrations in D. chrysantum (2.4-di-tert-butylphenol, 22.81%), D. chrysotoxum (1-octanol, and 2-phenylethanol, 2.80% and 2.36%), and D. wardianum (2-phenylethanol, 4.65%). Coumarin (95.59%) is the dominant compound in D. amabile (section Densiflora) and detected in lower concentrations (range 0.19–0.54%) in other samples. These volatile compounds may represent a particular feature of these plant species, playing a critical role in interacting with pollinators.

1. Introduction

2. Current Researches and Results

| Compound a | RI b | RI c | Section Dendrobium | Section Densiflora | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. chrysotoxum | D. harvejanum | D. wardianum | D. amabile | D. chrysanthum | Identification d | |||

| % | % | % | % | % | ||||

| Octane | 800 | 800 | - | 0.15 | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Hexanal | 802 | 801 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.02 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| 2-hexanol | 804 | 808 | - | 0.12 | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Diacetone alcohol | 841 | 841 | - | - | - | - | 0.68 | RI, NIST |

| α-pinene | 939 | 931 | 0.21 | - | - | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Benzaldehyde | 960 | 958 | 0.14 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| β-pinene | 979 | 973 | 0.03 | - | - | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Caproic acid | 1005 | 1003 | 0.06 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| α-terpinene | 1017 | 1015 | 0.10 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| o-Cymene | 1026 | 1023 | 0.09 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Limonene | 1029 | 1027 | 0.17 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Benzyl alchol | 1032 | 1035 | 0.21 | - | 0.52 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| β-Isophorone | 1042 | 1041 | 0.51 | - | - | - | RI, NIST | |

| Phenylacetaldehyde | 1042 | 1043 | 0.84 | - | 0.06 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| 2-octenal | 1056 | 1058 | - | 0.13 | - | - | 0.06 | RI, NIST |

| γ-Terpinene | 1060 | 1059 | 0.76 | - | 0.04 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Unidentified | - | 1065 | - | - | 2.89 | - | - | - |

| cis-sabinene hydrate | 1070 | 1067 | 0.27 | - | - | - | - | MS, NIST |

| dihydromyrcenol | 1073 | 1073 | - | 0.04 | - | - | 0.06 | RI, NIST |

| 1-octanol | 1070 | 1074 | 2.80 | - | 0.41 | - | - | MS, NIST |

| trans-sabinene hydrate | 1098 | 1098 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Linalool | 1097 | 1101 | 0.34 | 0.08 | - | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Nonanal | 1102 | 1105 | - | 0.16 | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| 2-phenylethanol | 1107 | 1115 | 2.36 | - | 4.65 | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Methyl octanoate | 1127 | 1127 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| cis-verbenol | 1141 | 1142 | 0.92 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| trans-verbenol | 1145 | 1148 | 4.60 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Camphor | 1150 | 1157 | - | 0.12 | - | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Nonenal | 1162 | 1161 | 0.41 | - | 0.17 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| α-phellandren-8-ol | 1170 | 1169 | 2.15 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1177 | 1179 | 1.53 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Diethyl succinate | 1182 | 1184 | 0.33 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| p-cymen-8-ol | 1183 | 1186 | 0.29 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| α-terpineol | 1189 | 1192 | 0.18 | - | - | - | 0.28 | RI, NIST |

| Ethyl octanoate | 1196 | 1199 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Decanal | 1202 | 1206 | - | - | 0.04 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Verbenone | 1205 | 1210 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | MS, NIST |

| 2,4-nonandienal | 1212 | 1214 | - | - | 0.03 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| 4-vinylphenol | 1224 | 1221 | - | - | 0.52 | 0.08 | - | RI, NIST |

| 3-phenyl-1-propanol | 1232 | 1231 | - | - | 0.08 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Phenylacetic acid ethyl ester | 1247 | 1247 | 0.15 | - | 0.72 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Nerol | 1254 | 1256 | 0.06 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| 2,4-decadienal (E,E) | 1291 | 1295 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.16 | - | RI, NIST |

| 2-methoxy-4-vinyl-phenol | 1315 | 1315 | - | - | 0.24 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| 2,4-decadienal (E,Z) | 1319 | 1317 | 0.63 | 0.88 | 0.48 | 0.72 | RI, NIST | |

| 2-nonenoic acid-γ-lactone | 1345 | 1344 | 0.39 | - | 0.49 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Capric acid | 1359 | 1359 | - | 0.32 | - | RI, NIST | ||

| Eugenol | 1367 | 1366 | - | - | - | 0.10 | - | RI, NIST |

| 1-tetradecene | 1390 | 1393 | - | 0.07 | - | 0.57 | MS, RI | |

| 3,4-dihydrocoumarin | 1398 | 1399 | - | - | - | 0.10 | - | RI, NIST |

| Coumarin | 1434 | 1436 | 0.71 | 0.19 | 0.54 | 95.49 | - | RI, NIST |

| 9-epi-(E)-caryophyllene | 1466 | 1458 | - | - | 1.32 | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Ethyl-cinnammate | 1467 | 1468 | - | - | 0.55 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol | 1494 | 1489 | - | 0.12 | 22.81 | MS, NIST | ||

| β-selinene | 1494 | 1489 | 0.25 | - | 1.30 | - | - | MS, NIST |

| 9-oxo-ethyl-nonanoate | 1507 | 1510 | 1.28 | - | - | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Lauric acid | 1566 | 1568 | 0.23 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Ethyl laurate | 1593 | 1596 | 0.15 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Unidentified | - | 1658 | - | 5.16 | - | - | - | - |

| Pentadecan-2-one | 1667 | 1667 | - | - | 0.26 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Heptadecane | 1700 | 1700 | 0.31 | - | 0.54 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Unidentified | - | 1767 | 0.39 | - | 3.04 | - | - | - |

| Myristic acid | 1780 | 1776 | - | 3.59 | - | - | MS, NIST | |

| 1-octadecene | 1790 | 1796 | 0.32 | - | 0.41 | - | - | MS, RI |

| Methyl pentadecanoate | 1820 | 1828 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Unidentified | - | 1879 | 5.74 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ethyl pentadecanoate | 1890 | 1896 | 0.36 | - | 0.19 | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Heptadecan-2-one | 1902 | 1903 | 0.11 | - | - | - | RI, NIST | |

| Methyl palmitate | 1927 | 1928 | 0.34 | - | 0.44 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| cis-9-hexadecenoic acid | 1942 | 1943 | - | - | - | - | 4.06 | RI, NIST |

| Z-11-Hexadecenoic acid | 1953 | 1953 | - | - | - | - | 29.22 | RI, NIST |

| Palmitic acid | 1958 | 1960 | 0.05 | 7.52 | 5.76 | 0.61 | 13.52 | RI, NIST |

| Neocembrene | 1960 | 1966 | 0.52 | - | 3.07 | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Ethyl palmitate | 1992 | 1997 | 3.05 | - | 0.99 | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Octadecan-1-ol | 2074 | 2071 | 0.17 | - | 0.60 | - | - | MS, NIST |

| Eicosane | 2000 | 2000 | - | 40.42 | - | - | 0.55 | RI, NIST |

| Unidentified | - | 2037 | - | 2.06 | - | - | - | |

| Methyl linoleate | 2051 | 2068 | 7.48 | 2.50 | 13.17 | - | 1.03 | MS, NIST |

| 10-Heneicosene | 2060 | 2073 | - | - | - | 0.43 | - | MS, RI |

| Heneicosane | 2100 | 2100 | 1.01 | 2.92 | 1.66 | 0.25 | - | RI, NIST |

| Linoleic acid | 2144 | 2147 | 0.12 | - | 17.54 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Ethyl linolenate | 2169 | 2171 | 26.98 | - | 32.24 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Ethyl oleate | 2179 | 2181 | 5.39 | - | 0.72 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Ethyl octadecanoate | 2193 | 2198 | 0.80 | - | 0.31 | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Docosane | 2200 | 2204 | 1.66 | 26.82 | - | 1.94 | 17.53 | RI, NIST |

| 9-Triacosene | 2279 | 2275 | 0.31 | - | - | - | - | MS, RI |

| Tricosane | 2300 | 2307 | 9.33 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Tetracosane | 2400 | 2401 | 0.40 | 0.90 | - | - | 2.07 | RI, NIST |

| 9-Pentacosene | 2474 | 2475 | 0.07 | - | - | MS, RI | ||

| Pentacosane | 2500 | 2501 | 0.95 | 6.53 | - | - | 6.40 | RI, NIST |

| Hexacosane | 2600 | 2600 | - | 2.46 | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| 9-Eptacosene | 2676 | 2676 | - | - | - | - | 1.15 | MS, RI |

| Heptacosane | 2700 | 2701 | 0.18 | - | - | - | - | RI, NIST |

| Aldehydes | 3.15 | 1.62 | 1.20 | 0.88 | 0.06 | |||

| Alcohols | 7.97 | 0.12 | 7.02 | 0.30 | 22.81 | |||

| Acids | 0.45 | 7.84 | 26.89 | 0.61 | 46.80 | |||

| Coumarin | 0.71 | 0.19 | 0.54 | 95.59 | - | |||

| Esters | 46.59 | 2.50 | 49.33 | - | 1.03 | |||

| Ketones | 0.62 | 0.12 | 0.26 | - | 0.68 | |||

| Saturated hydrocarbons | 22.84 | 80.20 | 2.20 | 2.19 | 26.55 | |||

| Unsaturated hydrocarbons | 0.69 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 1.72 | |||

| Terpenes | 2.04 | - | 5.73 | - | - | |||

| Oxygenated terpenes | 8.31 | 0.11 | - | - | 0.34 | |||

| Miscellanea | 0.48 | - | 0.49 | - | - | |||

| Unidentified | 6.13 | 7.22 | 5.92 | - | - | |||

3. Discussion

References

- Kaiser, R. The Scent of Orchids: Olfactory and Chemical Investigations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993.

- Ramya, M.; Jang, S.; An, H.R.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, P.M.; Park, P.H. Volatile organic compounds from orchids: From synthesis and function to gene regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1160.

- Schiestl, F.P.; Schlüter, P.M. Floral isolation, specialized pollination, and pollinator behavior in orchids. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2009, 54, 425–446.

- Takamiya, T.; Wongsawad, P.; Sathapattayanon, A.; Tajima, N.; Suzuki, S.; Kitamura, S.; Shioda, N.; Handa, T.; Kitanaka, S.; Iijima, H.; et al. Molecular phylogenetics and character evolution of morphologically diverse groups, Dendrobium section Dendrobium and allies. AoB Plants 2014, 6, plu045.

- Hinsley, A.; de Boer, H.J.; Fay, M.F.; Gale, S.W.; Gardiner, L.M.; Gunasekara, R.S.; Kumar, P.; Masters, S.; Metusala, D.; Roberts, D.L.; et al. A review of the trade in orchids and its implications for conservation. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2018, 186, 435–455.

- Teoh, E.S. Medicinal Orchids of Asia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016.

- Cheng, J.; Dang, P.; Zhao, Z.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, Z.; Wolf, D.; Luo, Y. An assessment of the Chinese medicinal Dendrobium industry: Supply, demand and sustainability. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 229, 81–88.

- Adams, P. Systematics of Dendrobiinae (Orchidaceae), with special reference to Australian taxa. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 166, 105–126.

- Xiang, X.G.; Schuiteman, A.; Li, D.Z.; Huang, W.C.; Chung, S.W.; Jianwu, L.; Zhou, H.L.; Jin, W.T.; Lai, Y.; Li, Z.Y.; et al. Molecular systematics of Dendrobium (Orchidaceae, Dendrobieae) from mainland Asia based on plastid and nuclear sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 69, 950–960.

- Stern, W.L.; Curry, K.J.; Whitten, W.M. Staining fragrance glands in orchid flowers. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club. 1986, 113, 288–297.

- Yukawa, T. Chloroplast DNA Phylogeny and Character Evolution of the Subtribe Dendrobiinae (Orchidaceae). Ph.D. Thesis, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan, 1993.

- Martin, K.P.; Madassery, J. Rapid in vitro propagation of Dendrobium hybrids through direct shoot formation from foliar explants, and protocorm-like bodies. Sci. Hortic. 2006, 108, 95–99.

- Teixeira da Silva, J.; Cardoso, J.; Dobránszki, J.; Zeng, S. Dendrobium micropropagation: A review. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 671–704.

- Calevo, J.; Copetta, A.; Marchioni, I.; Bazzicalupo, M.; Pianta, M.; Shirmohammadi, N.; Cornara, L.; Giovannini, A. The use of a new culture medium and organic supplement to improve in vitro early stage development of five orchid species. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2020.

- Carlsward, B.S.; Stern, W.; Judd, W.S.; Lucansky, T. Comparative leaf anatomy and systematics in Dendrobium, Sections Aporum and Rhizobium (Orchidaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 1997, 158, 332–342.

- Xu, J.; Han, Q.B.; Li, S.L.; Chen, X.J.; Wang, X.N.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Chen, H. Chemistry, bioactivity and quality control of Dendrobium, a commonly used tonic herb in traditional Chinese medicine. Phytochem. Rev. 2013, 12, 341–367.

- Devadas, R.; Pattanayak, S.; Singh, D.R. Studies on cross compatibility in Dendrobium species and hybrids. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2016, 76, 344–355.

- Shen, X.Y.; Liu, C.G.; Pan, K. Reproductive biological characteristics of Dendrobium species. In Reproductive Biology of Plants; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014.

- Flath, R.A.; Ohinata, K. Volatile components of the orchid Dendrobium superbum Rchb. f. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1982, 30, 841–842.

- Brodmann, J.; Twele, R.; Francke, W.; Yi-bo, L.; Xi-qiang, S.; Ayasse, M. Orchid mimics honey bee alarm pheromone in order to attract hornets for pollination. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1368–1372.

- Silva, R.; Uekane, T.M.; Rezende, C.M.; Bizzo, H.R. Floral volatile profile of Dendrobium nobile (Orchidaceae) in circadian cycle by dynamic headspace in vivo: Brazilian Symposium on Essential Oils. In Proceedings of the 8-International Symposium on Essential Oils, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 10–13 November 2015.

- Julsrigival, J.; Songsak, T.; Kirdmanee, C.; Chansakaow, S. Determination of volatile constituents of Thai fragrant orchids by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with solid-phase microextraction. Chiang Mai Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2013, 12.

- Robustelli della Cuna, F.S.; Boselli, C.; Papetti, A.; Calevo, J.; Mannucci, B.; Tava, A. Composition of volatile fraction from inflorescences and leaves of Dendrobium moschatum (Orchidaceae). Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 13, 93–96.

- Kjellsson, G.; Rasmussen, F.N. Does the pollination of Dendrobium unicum Seidenf. involve pseudopollen? Orchidee 1987, 34, 183–187.

- Inoue, K.; Kato, M.; Inoue, T. Pollination ecology of Dendrobium setifolium, Neuwiedia borneensis, and Lecanorchis multiflora (Orchidaceae) in Sarawak. Tropics 1995, 5, 95–100.

- Davies, K.; Turner, M. Pseudopollen in Dendrobium unicum Seidenf. (Orchidaceae): Reward or deception? Ann. Bot. 2004, 94, 129–132.

- Kamińska, M.; Stpiczyńska, M. The structure of the spur nectary in Dendrobium finisterrae Schltr. (Dendrobiinae, Orchidaceae). Acta Agrobot. 2011, 64, 19–26.

- Pang, S.; Pan, K.; Wang, Y.J.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.B. Floral morphology and reproductive biology of Dendrobium jiajiangense (Orchidaceae) in Mt. Fotang, southwestern China. Flora Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2012, 207, 469–474.

- Slater, A.; Calder, D. The pollination biology of Dendrobium speciosum Smith: A case of false advertising? Aust. J. Bot. 1988, 36, 145–158.

- Kjellsson, G.; Rasmussen, F.N.; Dupuy, D. Pollination of Dendrobium infundibulum, Cymbidium insigne (Orchidaceae) and Rhododendron lyi (Ericaceae) by Bombus eximius (Apidae) in Thailand: A possible case of floral mimicry. J. Trop. Ecol. 1985, 1, 289–302.

- Adams, R. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing Corporation: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007.

- Stein, S.E. NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Database; Version 2.1; Perkin-Elmer Instrument LLC: Waltham, MA, USA, 2000.

- Dobson, H.E.M. Relationship between floral fragrance composition and type of pollinator. In Biology of Floral Scent; Dudareva, N., Pichersky, E., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; p. 147.

- Witjes, S.; Witsch, K.; Eltz, T. Reconstructing the pollinator community and predicting seed set from hydrocarbon footprints on flowers. Oecologia 2011, 166, 161–174.

- Knudsen, J.T.; Eriksson, R.; Gershenzon, J.; Ståhl, B. Diversity and distribution of floral scent. Bot. Rev. 2006, 72, 1–20.

- Robustelli della Cuna, F.S.; Calevo, J.; Bari, E.; Giovannini, A.; Boselli, C.; Tava, A. Characterization and antioxidant activity of essential oil of four sympatric orchid species. Molecules 2019, 24, 3878.

- Knudsen, J.T.; Tollsten, L. Trends in floral scent chemistry in pollination syndromes. Floral scent composition in moth-pollinated taxa. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1993, 113, 263–284.

- Raguso, R.A. Floral Scent, Olfaction, and Scent-Driven Foraging Behavior, in Cognitive Ecology of Pollination; Chittka, L., Thomson, J.D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; p. 83.

- Ayasse, M.; Stokl, J.; Francke, W. Chemical ecology and pollinator-driven speciation in sexually deceptive orchids. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1667–1677.

- Pellegrino, G.; Luca, A.; Bellusci, F.; Musacchio, A. Comparative analysis of floral scents in four sympatric species of Serapias L. (Orchidaceae): Clues on their pollination strategies. Plant Syst. Evol. 2012, 298, 1837–1843.

- Arnold, S.E.J.; Forbes, S.J.; Hall, D.R.; Farman, D.I.; Bridgemohan, P.; Spinelli, G.R.; Bray, D.P.; Perry, G.B.; Grey, L.; Belmain, S.R.; et al. Floral odors and the interaction between pollinating Ceratopogonid midges and Cacao. J. Chem. Ecol. 2019, 45, 869–878.

- Waelti, M.O.; Muhlemann, K.; Widmer, A.; Schiestl, F.P. Floral odour and reproductive isolation in two species of Silene. J. Evol. Biol. 2008, 21, 111–121.

- Hu, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, F.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J. Variability of volatile compounds in the medicinal plant Dendrobium officinale from different regions. Molecules 2020, 25, 5046.

- Kim, B.R.; Kim, H.M.; Jin, C.H.; Kang, S.Y.; Kim, J.B.; Jeon, Y.G.; Park, K.Y.; Lee, I.S.; Han, A.R. Composition and antioxidant activities of volatile organic compounds in radiation-bred Coreopsis cultivars. Plants 2020, 9, 717.

- Da Silva, U.F.; Borba, E.L.; Semir, J.; Marsaioli, A. A simple solid injection device for the analyses of Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae) volatiles. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 31–34.

- Cseke, L.J.; Kaufman, P.B.; Kirakosyan, A. The biology of essential oils in the pollination of flowers. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 1317–1336.

- Xia, Y.H.; Ding, B.J.; Wang, H.L.; Hofvander, P.; Jarl-Sunesson, C.; Löfstedt, C. Production of moth sex pheromone precursors in Nicotiana spp.: A worthwhile new approach to pest control. J. Pest. Sci. 2020, 93, 1333–1346.

- Zhang, C.; Liu, S.J.; Yang, L.; Hu, J.M. Determination of volatile components from flowers of Dendrobium moniliforme (L.) Sw. in Yunnan by GC-MS. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. 2017, 32, 174–178.

- Huang, M.Z.; Li, X. Kind and content of volatile components in Gastrodia elata by SDE-GC-MS analysis. Guizhou Agric. Sci. 2018, 46, 110–113.

- Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Lucardi, R.D.; Su, Z.; Li, S. Natural sources and bioactivities of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol and its analogs. Toxins 2020, 12, 35.

- Niu, S.C.; Huang, J.; Xu, Q.; Li, P.X.; Yang, H.J.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, G.Q.; Chen, L.J.; Niu, Y.X.; Luo, Y.B.; et al. Morphological type identification of self-incompatibility in Dendrobium and its phylogenetic evolution pattern. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2595.

- Wang, Q.; Shao, S.; Su, Y.; Hu, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, D. A novel case of autogamy and cleistogamy in Dendrobium wangliangii: A rare orchid distributed in the dry-hot valley. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 12906–12914.