| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maria Sundvall | + 3500 word(s) | 3500 | 2021-09-09 04:44:51 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -13 word(s) | 3487 | 2021-09-22 05:58:50 | | |

Video Upload Options

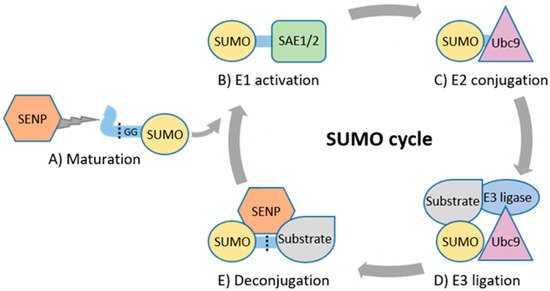

SUMOylation is a dynamic and reversible post-translational modification, characterized more than 20 years ago, that regulates protein function at multiple levels. Due to the reversible nature of this post-translational protein modification, the balance between SUMOylation and the removal of SUMO is critical. SUMO pathway regulates the hallmark properties of cancer cells. Moreover, alterations in activity and in levels of SUMO machinery components have been observed in human cancer. Many molecular mechanisms relevant to the pathogenesis of specific cancers involve SUMO, highlighting the potential relevance of SUMO machinery components as therapeutic targets. Early-phase clinical trials are currently evaluating the safety and efficacy of SUMO pathway inhibition in cancer patients.

1. Introduction

2. Basic Principles of SUMOylation and Its Role in Physiology

3. Altered Expression and Prognostic Significance of SUMO Pathway in Cancer

| High Expression Associates with Poor Prognosis |

High Expression Associates with Good Prognosis |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Type | Protein(s) | Cancer Type | Protein(s) |

| adrenocortical | PIAS3, PIAS4, SAE1, SAE2, SENP1, SENP3, SUMO1, SUMO2, SUMO4 | bladder | Ubc9 |

| breast | PC2, PIAS3, PIAS4, SAE1, SAE2, SENP5, SENP7L, SUMO1, SUMO2, SUMO3, Ubc9 | breast | PC2, PIAS1, PIAS4 |

| colorectal | SAE2, SENP1, SUMO1 | cervical | PIAS3 |

| gastric | PC2, PIAS2, SAE2, SUMO3, Ubc9 | colorectal | PC2 |

| glioma | SAE1, Ubc9 | gastric | PIAS1, PIAS4 |

| hepatocellular | PC2, PIAS2, PIAS3, PIAS4, SAE1, SAE2, SENP1, SENP3, SENP5, SENP6, SUMO2, Ubc9 | glioma | PIAS3 |

| leukemia | SAE1, SUMO3 | leukemia | PIAS2, SENP5, SENP7 |

| lung | PC2, SAE1, SAE2, SENP1, SUMO2/3, SUMO4, Ubc9 | lung | PIAS3 |

| melanoma (cutaneous) | SAE1 | melanoma (cutaneous) | PIAS1, SENP5, SENP7 |

| melanoma (uveal) | SAE1, SAE2, SUMO3 | melanoma (uveal) | SENP2, Ubc9 |

| mesothelioma | PIAS3, PIAS4, SAE1, SAE2, SENP1 | mesothelioma | PC2, PIAS3, SENP2 |

| multiple myeloma | Ubc9 | ovarian | PIAS2 |

| osteosarcoma | PC2, SENP3 | pancreatic | SENP3 |

| ovarian | SENP3, SENP5 | pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma | Ubc9 |

| pancreatic | SENP2, (SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 together), Ubc9 | renal | PIAS1, PIAS2 |

| prostate | PIAS1, SAE1, SENP1, SENP5, SUMO1, SUMO2 | testicular germ cell | PIAS2 |

| renal | PC2, PIAS3, RSUME, SAE1, SENP1, SENP3, SENP5, SUMO1, SUMO2, Ubc9 | thymoma | PIAS4, SAE1, SAE2, SENP1, Ubc9 |

| sarcoma | PC2, PIAS2, PIAS3, SENP6, SENP7 | ||

| thyroid | PIAS2, SAE1 | ||

| uterine corpus endometrial | PC2, SAE2, SENP2, SENP5, SUMO4 | ||

Regulation of SUMO Machinery Expression and Activity in Cancer

4. Genetic Changes Targeting SUMO Machinery in Cancer

4.1. Germline Variants

4.2. Somatic Mutations

5. SUMOylation Regulates Key Cancer Genes and Hallmark Properties of Cancer Cells

5.1. Substrates of SUMO Relevant for Cancer

5.2. SUMOylation in Cellular Processes Relevant for Cancer

The article is from 10.3390/cancers13174402, a comprehensive review that also in detail discusses the SUMO-modulated molecular mechanisms and scientific rationale of targeting the SUMO pathway in different cancer types, using the best-characterized hematological malignancies and solid tumors as examples. Moreover, the properties and activity of pharmacological preclinical inhibitors of the SUMO pathway components (SAE1/2, Ubc9 and SENPs) as well as the clinical development of the SAE inhibitor, TAK-981, which is the only SUMO pathway inhibitor that has progressed to clinical trials in cancer patients are explored.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Prabakaran, S.; Lippens, G.; Steen, H.; Gunawardena, J. Post-translational modification: Nature’s escape from genetic imprisonment and the basis for dynamic information encoding. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2012, 4, 565–583.

- Conibear, A.C. Deciphering protein post-translational modifications using chemical biology tools. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 674–695.

- Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Tao, Y. Regulating tumor suppressor genes: Post-translational modifications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 90.

- Xue, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, F.; Wang, J. Emerging Role of Protein Post-Translational Modification in the Potential Clinical Application of Cancer. Nano Life 2020, 10, 2040008.

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, Q.; Li, L.; Jia, L. Neddylation: A novel modulator of the tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 77.

- Deng, L.; Meng, T.; Chen, L.; Wei, W.; Wang, P. The role of ubiquitination in tumorigenesis and targeted drug discovery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 11.

- Celen, A.B.; Sahin, U. Sumoylation on its 25th anniversary: Mechanisms, pathology, and emerging concepts. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3110–3140.

- Geiss-Friedlander, R.; Melchior, F. Concepts in sumoylation: A decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 947–956.

- Sundvall, M. Role of ubiquitin and SUMO in intracellular trafficking. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2020, 35, 99–108.

- Psakhye, I.; Jentsch, S. Protein group modification and synergy in the SUMO pathway as exemplified in DNA repair. Cell 2012, 151, 807–820.

- Vijay-Kumar, S.; Bugg, C.E.; Cook, W.J. Structure of ubiquitin refined at 1.8 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1987, 194, 531–544.

- Bayer, P.; Arndt, A.; Metzger, S.; Mahajan, R.; Melchior, F.; Jaenicke, R.; Becker, J. Structure determination of the small ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 280, 275–286.

- Guo, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, P.; Eckenrode, S.; Hopkins, D.; Zheng, W.; Purohit, S.; Podolsky, R.H.; Muir, A.; et al. A functional variant of SUMO4, a new IκBα modifier, is associated with type diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 837–841.

- Bohren, K.M.; Nadkarni, V.; Song, J.H.; Gabbay, K.H.; Owerbach, D. A M55V polymorphism in a novel SUMO gene (SUMO-4) differentially activates heat shock transcription factors and is associated with susceptibility to type I diabetes mellitus. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 27233–27238.

- Wang, L.; Wansleeben, C.; Zhao, S.; Miao, P.; Paschen, W.; Yang, W. SUMO 2 is essential while SUMO 3 is dispensable for mouse embryonic development. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 878–885.

- Liang, Y.C.; Lee, C.C.; Yao, Y.L.; Lai, C.C.; Schmitz, M.L.; Yang, W.M. SUMO5, a novel poly-SUMO isoform, regulates PML nuclear bodies. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26509.

- Gareau, J.R.; Lima, C.D. The SUMO pathway: Emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 861–871.

- Hendriks, I.A.; D’Souza, R.C.J.; Yang, B.; Verlaan-De Vries, M.; Mann, M.; Vertegaal, A.C.O. Uncovering global SUMOylation signaling networks in a site-specific manner. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 927–936.

- Tammsalu, T.; Matic, I.; Jaffray, E.G.; Ibrahim, A.F.M.; Tatham, M.H.; Hay, R.T. Proteome-wide identification of SUMO2 modification sites. Sci. Signal. 2014, 7, rs2.

- Tatham, M.H.; Jaffray, E.; Vaughan, O.A.; Desterro, J.M.P.; Botting, C.H.; Naismith, J.H.; Hay, R.T. Polymeric Chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are Conjugated to Protein Substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 35368–35374.

- Matic, I.; van Hagen, M.; Schimmel, J.; Macek, B.; Ogg, S.C.; Tatham, M.H.; Hay, R.T.; Lamond, A.I.; Mann, M.; Vertegaal, A.C.O. In vivo identification of human small ubiquitin-like modifier polymerization sites by high accuracy mass spectrometry and an in vitro to in vivo strategy. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2008, 7, 132–144.

- Song, J.; Durrin, L.K.; Wilkinson, T.A.; Krontiris, T.G.; Chen, Y. Identification of a SUMO-binding motif that recognizes SUMO-modified proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14373–14378.

- Hecker, C.M.; Rabiller, M.; Haglund, K.; Bayer, P.; Dikic, I. Specification of SUMO1- and SUMO2-interacting motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 16117–16127.

- Kunz, K.; Piller, T.; Müller, S. SUMO-specific proteases and isopeptidases of the SENP family at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs211904.

- Gan-Erdene, T.; Nagamalleswari, K.; Yin, L.; Wu, K.; Pan, Z.Q.; Wilkinson, K.D. Identification and characterization of DEN1, a deneddylase of the ULP family. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 28892–28900.

- Nayak, A.; Müller, S. SUMO-specific proteases/isopeptidases: SENPs and beyond. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 422.

- Johnson, E.S.; Schwienhorst, I.; Dohmen, R.J.; Blobel, G. The ubiquitin-like protein Smt3p is activated for conjugation to other proteins by an Aos1p/Uba2p heterodimer. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 5509–5519.

- Desterro, J.M.P.; Rodriguez, M.S.; Kemp, G.D.; Ronald, T.H. Identification of the enzyme required for activation of the small ubiquitin-like protein SUMO-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 10618–10624.

- Okuma, T.; Honda, R.; Ichikawa, G.; Tsumagari, N.; Yasuda, H. In vitro SUMO-1 modification requires two enzymatic steps, E1 and E2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 254, 693–698.

- Rytinki, M.M.; Kaikkonen, S.; Pehkonen, P.; Jääskeläinen, T.; Palvimo, J.J. PIAS proteins: Pleiotropic interactors associated with SUMO. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 3029–3041.

- Rabellino, A.; Andreani, C.; Scaglioni, P.P. The Role of PIAS SUMO E3-Ligases in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 1542–1547.

- Pichler, A.; Gast, A.; Seeler, J.S.; Dejean, A.; Melchior, F. The nucleoporin RanBP2 has SUMO1 E3 ligase activity. Cell 2002, 108, 109–120.

- Cappadocia, L.; Pichler, A.; Lima, C.D. Structural basis for catalytic activation by the human ZNF451 SUMO E3 ligase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 968–975.

- Kagey, M.H.; Melhuish, T.A.; Wotton, D. The polycomb protein Pc2 is a SUMO E3. Cell 2003, 113, 127–137.

- Chu, Y.; Yang, X. SUMO E3 ligase activity of TRIM proteins. Oncogene 2011, 30, 1108–1116.

- Li, M.; Xu, X.; Chang, C.W.; Liu, Y. TRIM28 functions as the SUMO E3 ligase for PCNA in prevention of transcription induced DNA breaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 23588–23596.

- Hietakangas, V.; Anckar, J.; Blomster, H.A.; Fujimoto, M.; Palvimo, J.J.; Nakai, A.; Sistonen, L. PDSM, a motif for phosphorylation-dependent SUMO modification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 45–50.

- Stabell, M.; Sæther, T.; Røhr, Å.K.; Gabrielsen, O.S.; Myklebost, O. Methylation-dependent SUMOylation of the architectural transcription factor HMGA2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 552, 91–97.

- Anckar, J.; Sistonen, L. SUMO: Getting it on. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1409–1413.

- Nacerddine, K.; Lehembre, F.; Bhaumik, M.; Artus, J.; Cohen-Tannoudji, M.; Babinet, C.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Dejean, A. The SUMO pathway is essential for nuclear integrity and chromosome segregation in mice. Dev. Cell 2005, 9, 769–779.

- Zhang, F.-P.; Mikkonen, L.; Toppari, J.; Palvimo, J.J.; Thesleff, I.; Jänne, O.A. Sumo-1 Function Is Dispensable in Normal Mouse Development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 5381–5390.

- Cheng, J.; Kang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yeh, E.T.H. SUMO-Specific Protease 1 Is Essential for Stabilization of HIF1α during Hypoxia. Cell 2007, 131, 584–595.

- Chiu, S.Y.; Asai, N.; Costantini, F.; Hsu, W. SUMO-specific protease 2 is essential for modulating p53-mdm2 in development of trophoblast stem cell niches and lineages. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e310.

- Lao, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Zou, Q.; Yu, X.; Cheng, J.; Tong, X.; Yeh, E.T.H.; Yang, J.; et al. DeSUMOylation of MKK7 kinase by the SUMO2/3 protease SENP3 potentiates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory signaling in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 3965–3980.

- Liu, B.; Mink, S.; Wong, K.A.; Stein, N.; Getman, C.; Dempsey, P.W.; Wu, H.; Shuai, K. PIAS1 selectively inhibits interferon-inducible genes and is important in innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 891–898.

- Roth, W.; Sustmann, C.; Kieslinger, M.; Gilmozzi, A.; Irmer, D.; Kremmer, E.; Turck, C.; Grosschedl, R. PIASy-Deficient Mice Display Modest Defects in IFN and Wnt Signaling. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 6189–6199.

- Santti, H.; Mikkonen, L.; Anand, A.; Hirvonen-Santti, S.; Toppari, J.; Panhuysen, M.; Vauti, F.; Perera, W.; Corte, G.; Wurst, W.; et al. Disruption of the murine PIASx gene results in reduced testis weight. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 34, 645–654.

- Campla, C.K.; Breit, H.; Dong, L.; Gumerson, J.D.; Roger, J.E.; Swaroop, A. Pias3 is necessary for dorso-ventral patterning and visual response of retinal cones but is not required for rod photoreceptor differentiation. Biol. Open 2017, 6, 881–890.

- Lee, J.S.; Chu, I.S.; Heo, J.; Calvisi, D.F.; Sun, Z.; Roskams, T.; Durnez, A.; Demetris, A.J.; Thorgeirsson, S.S. Classification and prediction of survival in hepatocellular carcinoma by gene expression profiling. Hepatology 2004, 40, 667–676.

- Shen, H.J.; Zhu, H.Y.; Yang, C.; Ji, F. SENP2 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth by modulating the stability of β-catenin. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 3583–3587.

- Tan, M.Y.; Mu, X.Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Bao, E.D.; Qiu, J.X.; Fan, Y. SUMO-specific protease 2 suppresses cell migration and invasion through inhibiting the expression of MMP13 in bladder cancer cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 32, 542–548.

- Pei, H.; Chen, L.; Liao, Q.M.; Wang, K.J.; Chen, S.G.; Liu, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.C. Sumo-specific protease 2 (Senp2) functions as a tumosuppressor in osteosarcoma via sox9 degradation. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 5359–5365.

- Chen, X.L.; Wang, S.F.; Liang, X.T.; Liang, H.X.; Wang, T.T.; Wu, S.Q.; Qiu, Z.J.; Zhan, R.; Xu, Z.S. SENP2 exerts an anti-tumor effect on chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells through the inhibition of the Notch and NF-κB signaling pathways. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 455–466.

- Xie, H.; Gu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Ye, X.; Xin, C.; Lu, M.; Reddy, B.A.; Shu, P. Silencing of SENP2 in Multiple Myeloma Induces Bortezomib Resistance by Activating NF-κB Through the Modulation of IκBα Sumoylation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 766.

- Li, X.; Meng, Y. SUMOylation Regulator-Related Molecules Can Be Used as Prognostic Biomarkers for Glioblastoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 689.

- Taheri, M.; Oskooei, V.K.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. Protein inhibitor of activated STAT genes are differentially expressed in breast tumor tissues. Pers. Med. 2019, 16, 277–285.

- Tuccilli, C.; Baldini, E.; Sorrenti, S.; Di Gioia, C.; Bosco, D.; Ascoli, V.; Mian, C.; Barollo, S.; Rendina, R.; Coccaro, C.; et al. Papillary thyroid cancer is characterized by altered expression of genes involved in the sumoylation process. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2015, 29, 655–662.

- Wang, J.; Ni, J.; Yi, S.; Song, D.; Ding, M. Protein inhibitor of activated STAT xα depresses cyclin D and cyclin D kinase, and contributes to the inhibition of osteosarcoma cell progression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 1645–1652.

- Zeng, J.S.; Zhang, Z.D.; Pei, L.; Bai, Z.Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Tian, Q.H. CBX4 exhibits oncogenic activities in breast cancer via Notch1 signaling. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 95, 1–8.

- Li, X.; Gou, J.; Li, H.; Yang, X. Bioinformatic analysis of the expression and prognostic value of chromobox family proteins in human breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17739.

- Alshareeda, A.T.; Negm, O.H.; Green, A.R.; Nolan, C.; Tighe, P.; Albarakati, N.; Sultana, R.; Madhusudan, S.; Ellis, I.O.; Rakha, E.A. SUMOylation proteins in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 144, 519–530.

- Agboola, A.; Musa, A.; Banjo, A.; Ayoade, B.; Deji-Agboola, M.; Nolan, C.; Rakha, E.; Ellis, I.; Green, A. PIASγ expression in relation to clinicopathological, tumour factors and survival in indigenous black breast cancer women. J. Clin. Pathol. 2014, 67, 301–306.

- Dabir, S.; Kluge, A.; Kresak, A.; Yang, M.; Fu, P.; Groner, B.; Wildey, G.; Dowlati, A. Low PIAS3 expression in malignant mesothelioma is associated with increased STAT3 activation and poor patient survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 5124–5132.

- Wu, G.; Xu, Y.; Ruan, N.; Li, J.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xia, Q.; Li, Q. Genetic alteration and clinical significance of sumoylation regulators in multiple cancer types. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 6823–6833.

- Yang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Gu, Q.; Shen, G.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, H.; et al. SAE1 promotes human glioma progression through activating AKT SUMOylation-mediated signaling pathways. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 1–14.

- Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Long, X.D.; Wang, W.; Jiao, H.K.; Mei, Z.; Yin, Q.Q.; Ma, L.N.; Zhou, A.W.; Wang, L.S.; et al. Cbx4 governs HIF-1α to potentiate angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma by its SUMO E3 ligase activity. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 118–131.

- Jiao, H.K.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Mei, Z.; Long, X.D.; Chen, G.Q. Prognostic significance of Cbx4 expression and its beneficial effect for transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1689.

- Chanda, A.; Chan, A.; Deng, L.; Kornaga, E.N.; Enwere, E.K.; Morris, D.G.; Bonni, S. Identification of the SUMO E3 ligase PIAS1 as a potential survival biomarker in breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177639.

- Wang, B.; Tang, J.; Liao, D.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.; Sang, Y.; Cao, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, S.; et al. Chromobox homolog 4 is correlated with prognosis and tumor cell growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20, 684–692.

- Qian, J.; Luo, Y.; Gu, X.; Wang, X. Inhibition of SENP6-Induced Radiosensitization of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells by Blocking Radiation-Induced NF-κB Activation. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2013, 28, 196–200.

- Stefanska, B.; Cheishvili, D.; Suderman, M.; Arakelian, A.; Huang, J.; Hallett, M.; Han, Z.G.; Al-Mahtab, M.; Akbar, S.M.F.; Khan, W.A.; et al. Genome-wide study of hypomethylated and induced genes in patients with liver cancer unravels novel anticancer targets. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 3118–3132.

- Zhao, Z.; Tan, X.; Zhao, A.; Zhu, L.; Yin, B.; Yuan, J.; Qiang, B.; Peng, X. microRNA-214-mediated UBC9 expression in glioma. BMB Rep. 2012, 45, 641–646.

- Yang, H.; Tang, Y.; Guo, W.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Zang, W.; Yin, X.; Wang, H.; Chu, H.; et al. Up-regulation of microRNA-138 induce radiosensitization in lung cancer cells. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 6557–6565.

- Wang, C.; Tao, W.; Ni, S.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, L.; Fu, Y.; Jiao, Z. Tumor-suppressive microRNA-145 induces growth arrest by targeting SENP1 in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2015, 106, 375–382.

- Zheng, C.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, W.; Zhou, J.; Liu, R.; Zeng, Q.; Peng, X.; Huang, C.; Cao, P.; et al. MicroRNA-195 functions as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting CBX4 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 1115–1122.

- Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, H.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Y.; Xue, W.; Pu, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-497-5p induces cell cycle arrest of cervical cancer cells in s phase by targeting cbx4. Onco-Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 10535–10545.

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, R.; Liu, P.; Ye, Y.; Yu, W.; Guo, X.; Yu, J. Cancer exosome-derived miR-9 and miR-181a promote the development of early-stage MDSCs via interfering with SOCS3 and PIAS3 respectively in breast cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4681–4694.

- Kluge, A.; Dabir, S.; Vlassenbroeck, I.; Eisenberg, R.; Dowlati, A. Protein inhibitor of activated STAT3 expression in lung cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2011, 5, 256–264.

- Brantley, E.C.; Nabors, L.B.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Choi, Y.H.; Palmer, C.A.; Harrison, K.; Roarty, K.; Benveniste, E.N. Loss of protein inhibitors of activated STAT-3 expression in glioblastoma multiforme tumors: Implications for STAT-3 activation and gene expression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4694–4704.

- Huang, C.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Yan, S.; Yeh, E.T.H.; Chen, Y.; Cang, H.; Li, H.; Shi, G.; et al. SENP3 is responsible for HIF-1 transactivation under mild oxidative stress via p300 de-SUMOylation. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 2748–2762.

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Xiao, M.; Chin, Y.E.; Cheng, J.; Yeh, E.T.H.; Yang, J.; Yi, J. SUMOylation and SENP3 regulate STAT3 activation in head and neck cancer. Oncogene 2016, 35, 5826–5838.

- Kunz, K.; Wagner, K.; Mendler, L.; Hölper, S.; Dehne, N.; Müller, S. SUMO Signaling by Hypoxic Inactivation of SUMO-Specific Isopeptidases. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 3075–3086.

- Kang, X.; Li, J.; Zou, Y.; Yi, J.; Zhang, H.; Cao, M.; Yeh, E.T.H.; Cheng, J. PIASy stimulates HIF1α SUMOylation and negatively regulates HIF1α activity in response to hypoxia. Oncogene 2010, 29, 5568–5578.

- Dünnebier, T.; Bermejo, J.L.; Haas, S.; Fischer, H.P.; Pierl, C.B.; Justenhoven, C.; Brauch, H.; Baisch, C.; Gilbert, M.; Harth, V.; et al. Common variants in the UBC9 gene encoding the SUMO-conjugating enzyme are associated with breast tumor grade. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 596–602.

- Dünnebier, T.; Bermejo, J.L.; Haas, S.; Fischer, H.P.; Pierl, C.B.; Justenhoven, C.; Brauch, H.; Baisch, C.; Gilbert, M.; Harth, V.; et al. Polymorphisms in the UBC9 and PIAS3 genes of the SUMO-conjugating system and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 121, 185–194.

- Mirecka, A.; Morawiec, Z.; Wozniak, K. Genetic Polymorphism of SUMO-Specific Cysteine Proteases—SENP1 and SENP2 in Breast Cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2016, 22, 817–823.

- Luo, Y.; You, S.; Wang, J.; Fan, S.; Shi, J.; Peng, A.; Yu, T. Association between sumoylation-related gene rs77447679 polymorphism and risk of gastric cancer(GC) in a Chinese population. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 3226–3231.

- Murakami, H.; Arnheiter, H. Sumoylation modulates transcriptional activity of MITF in a promoter-specific manner. Pigment Cell Res. 2005, 18, 265–277.

- Bertolotto, C.; Lesueur, F.; Giuliano, S.; Strub, T.; De Lichy, M.; Bille, K.; Dessen, P.; D’Hayer, B.; Mohamdi, H.; Remenieras, A.; et al. A SUMOylation-defective MITF germline mutation predisposes to melanoma and renal carcinoma. Nature 2011, 480, 94–98.

- King, R.; Weilbaecher, K.N.; McGill, G.; Cooley, E.; Mihm, M.; Fisher, D.E. Microphthalmia transcription factor: A sensitive and specific melanocyte marker for melanoma diagnosis. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 155, 731–738.

- Buscà, R.; Berra, E.; Gaggioli, C.; Khaled, M.; Bille, K.; Marchetti, B.; Thyss, R.; Fitsialos, G.; Larribère, L.; Bertolotto, C.; et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α is a new target of microphthalmia- associated transcription factor (MITF) in melanoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 170, 49–59.

- Linehan, W.M.; Srinivasan, R.; Schmidt, L.S. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: A metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2010, 7, 277–285.

- Levin, N.A.; Bnorka, P.M.; Warnock, M.L.; Gray, J.W.; Christman, M.F. Identification of novel regions of altered DNA copy number in small cell lung tumors. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 1995, 13, 175–185.

- Wang, J.; Qian, J.; Hoeksema, M.D.; Zou, Y.; Espinosa, A.V.; Rahman, S.M.J.; Zhang, B.; Massion, P.P. Integrative genomics analysis identifies candidate drivers at 3q26-29 amplicon in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 5580–5590.

- Fields, A.P.; Justilien, V.; Murray, N.R. The chromosome 3q26 OncCassette: A multigenic driver of human cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2016, 60, 47–63.

- La-Touche, S.; Lemetre, C.; Lambros, M.; Stankiewicz, E.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Weigelt, B.; Rajab, R.; Tinwell, B.; Corbishley, C.; Watkin, N.; et al. DNA Copy Number Aberrations, and Human Papillomavirus Status in Penile Carcinoma. Clinico-Pathological Correlations and Potential Driver Genes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146740.

- Constanzo, J.D.; Tang, K.J.; Rindhe, S.; Melegari, M.; Liu, H.; Tang, X.; Rodriguez-Canales, J.; Wistuba, I.; Scaglioni, P.P. PIAS1-FAK Interaction Promotes the Survival and Progression of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Neoplasia 2016, 18, 282–293.

- Veltman, I.M.; Vreede, L.A.; Cheng, J.; Looijenga, L.H.J.; Janssen, B.; Schoenmakers, E.F.P.M.; Yeh, E.T.H.; van Kessel, A.G. Fusion of the SUMO/Sentrin-specific protease 1 gene SENP1 and the embryonic polarity-related mesoderm development gene MESDC2 in a patient with an infantile teratoma and a constitutional t(12;15)(q13;q25). Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1955–1963.

- Tagawa, H.; Miura, I.; Suzuki, R.; Suzuki, H.; Hosokawa, Y.; Seto, M. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of the breakpoint region at 6q21-22 in T-cell lymphoma/leukemia cell lines. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 2002, 34, 175–185.

- Xu, H.D.; Shi, S.P.; Chen, X.; Qiu, J.D. Systematic analysis of the genetic variability that impacts sumo conjugation and their involvement in human diseases. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10900.

- Chen, L.; Miao, Y.; Liu, M.; Zeng, Y.; Gao, Z.; Peng, D.; Hu, B.; Li, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xue, Y.; et al. Pan-cancer analysis reveals the functional importance of protein lysine modification in cancer development. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 254.

- Kessler, J.D.; Kahle, K.T.; Sun, T.; Meerbrey, K.L.; Schlabach, M.R.; Schmitt, E.M.; Skinner, S.O.; Xu, Q.; Li, M.Z.; Hartman, Z.C.; et al. A SUMOylation-dependent transcriptional subprogram is required for Myc-driven tumorigenesis. Science 2012, 335, 348–353.

- González-Prieto, R.; Cuijpers, S.A.G.; Kumar, R.; Hendriks, I.A.; Vertegaal, A.C.O. c-Myc is targeted to the proteasome for degradation in a SUMOylation-dependent manner, regulated by PIAS1, SENP7 and RNF4. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 1859–1872.

- Rabellino, A.; Melegari, M.; Tompkins, V.S.; Chen, W.; Van Ness, B.G.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Conacci-Sorrell, M.; Janz, S.; Scaglioni, P.P. PIAS1 Promotes Lymphomagenesis through MYC Upregulation. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 2266–2278.

- Sun, X.X.; Chen, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Chauhan, K.M.; Liang, J.; Daniel, C.J.; Sears, R.C.; Dai, M.S. SUMO protease SENP1 deSUMOylates and stabilizes c-Myc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10983–10988.

- Yu, B.; Swatkoski, S.; Holly, A.; Lee, L.C.; Giroux, V.; Lee, C.S.; Hsu, D.; Smith, J.L.; Yuen, G.; Yue, J.; et al. Oncogenesis driven by the Ras/Raf pathway requires the SUMO E2 ligase Ubc9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E1724–E1733.

- Li, R.; Wei, J.; Jiang, C.; Liu, D.; Deng, L.; Zhang, K.; Wang, P. Akt SUMOylation regulates cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 5742–5753.

- Yan, Y.; Ollila, S.; Wong, I.P.L.; Vallenius, T.; Palvimo, J.J.; Vaahtomeri, K.; Mäkelä, T.P. SUMOylation of AMPKα1 by PIAS4 specifically regulates mTORC1 signalling. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8979.

- Bae, S.H.; Jeong, J.W.; Park, J.A.; Kim, S.H.; Bae, M.K.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, K.W. Sumoylation increases HIF-1α stability and its transcriptional activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 324, 394–400.

- Carbia-Nagashima, A.; Gerez, J.; Perez-Castro, C.; Paez-Pereda, M.; Silberstein, S.; Stalla, G.K.; Holsboer, F.; Arzt, E. RSUME, a Small RWD-Containing Protein, Enhances SUMO Conjugation and Stabilizes HIF-1α during Hypoxia. Cell 2007, 131, 309–323.

- Lee, M.H.; Mabb, A.M.; Gill, G.B.; Yeh, E.T.H.; Miyamoto, S. NF-κB Induction of the SUMO Protease SENP2: A Negative Feedback Loop to Attenuate Cell Survival Response to Genotoxic Stress. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 180–191.

- Choi, H.K.; Choi, K.C.; Yoo, J.Y.; Song, M.; Ko, S.J.; Kim, C.H.; Ahn, J.H.; Chun, K.H.; Yook, J.I.; Yoon, H.G. Reversible SUMOylation of TBL1-TBLR1 Regulates β-Catenin-Mediated Wnt Signaling. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 203–216.

- Sharma, P.; Kuehn, M.R. SENP1-modulated sumoylation regulates retinoblastoma protein (RB) and Lamin A/C interaction and stabilization. Oncogene 2016, 35, 6429–6438.

- Gostissa, M.; Hengstermann, A.; Fogal, V.; Sandy, P.; Schwarz, S.E.; Scheffner, M.; Del Sal, G. Activation of p53 by conjugation to the ubiquitin-like protein SUMO-1. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 6462–6471.

- Rodriguez, M.S.; Desterro, J.M.P.; Lain, S.; Midgley, C.A.; Lane, D.P.; Hay, R.T. SUMO-1 modification activates the transcriptional response of p53. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 6455–6461.

- Xirodimas, D.P.; Chisholm, J.; Desterro, J.M.; Lane, D.P.; Hay, R.T. P14ARF promotes accumulation of SUMO-1 conjugated (H)Mdm2. FEBS Lett. 2002, 528, 207–211.

- Chen, L.; Chen, J. MDM2-ARF complex regulates p53 sumoylation. Oncogene 2003, 22, 5348–5357.

- Jiang, M.; Chiu, S.Y.; Hsu, W. SUMO-specific protease 2 in Mdm2-mediated regulation of p53. Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18, 1005–1015.

- Lee, Y.-R.; Chen, M.; Pandolfi, P.P. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor: New modes and prospects. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 547–562.

- Huang, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, T.; Zhu, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Cheng, J.; et al. SUMO1 modification of PTEN regulates tumorigenesis by controlling its association with the plasma membrane. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 911.

- Bassi, C.; Ho, J.; Srikumar, T.; Dowling, R.J.O.; Gorrini, C.; Miller, S.J.; Mak, T.W.; Neel, B.G.; Raught, B.; Stambolic, V. Nuclear PTEN controls DNA repair and sensitivity to genotoxic stress. Science 2013, 341, 395–399.

- Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, N.; Cao, Z.; Wang, W.; Tong, T.; Zhang, X. PIASxα ligase enhances SUMO1 modification of PTEN Protein as a SUMO E3 Ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 3217–3230.

- Galanty, Y.; Belotserkovskaya, R.; Coates, J.; Polo, S.; Miller, K.M.; Jackson, S.P. Mammalian SUMO E3-ligases PIAS1 and PIAS4 promote responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 2009, 462, 935–939.

- Shim, H.S.; Wei, M.; Brandhorst, S.; Longo, V.D. Starvation promotes REV1 SUMOylation and p53-dependent sensitization of melanoma and breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 1056–1067.

- Niskanen, E.A.; Malinen, M.; Sutinen, P.; Toropainen, S.; Paakinaho, V.; Vihervaara, A.; Joutsen, J.; Kaikkonen, M.U.; Sistonen, L.; Palvimo, J.J. Global SUMOylation on active chromatin is an acute heat stress response restricting transcription. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 153.

- Zhu, X.; Ding, S.; Qiu, C.; Shi, Y.; Song, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. SUMOylation negatively regulates angiogenesis by targeting endothelial NOTCH signaling. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 636–649.

- Zhang, C.; Mukherjee, S.; Tucker-Burden, C.; Ross, J.L.; Chau, M.J.; Kong, J.; Brat, D.J. TRIM8 regulates stemness in glioblastoma through PIAS3-STAT3. Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 280–294.

- Hannoun, Z.; Maarifi, G.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K. The implication of SUMO in intrinsic and innate immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016, 29, 3–16.

- Garvin, A.J.; Densham, R.M.; Blair-Reid, S.A.; Pratt, K.M.; Stone, H.R.; Weekes, D.; Lawrence, K.J.; Morris, J.R. The deSUMOylase SENP7 promotes chromatin relaxation for homologous recombination DNA repair. EMBO Rep. 2013, 14, 975–983.

- Wagner, K.; Kunz, K.; Piller, T.; Tascher, G.; Hölper, S.; Stehmeier, P.; Keiten-Schmitz, J.; Schick, M.; Keller, U.; Müller, S. The SUMO Isopeptidase SENP6 Functions as a Rheostat of Chromatin Residency in Genome Maintenance and Chromosome Dynamics. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 480–494.e5.

- Garvin, A.J.; Walker, A.K.; Densham, R.M.; Chauhan, A.S.; Stone, H.R.; Mackay, H.L.; Jamshad, M.; Starowicz, K.; Daza-Martin, M.; Ronson, G.E.; et al. The deSUMOylase SENP2 coordinates homologous recombination and nonhomologous end joining by independent mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 333–347.

- Despras, E.; Sittewelle, M.; Pouvelle, C.; Delrieu, N.; Cordonnier, A.M.; Kannouche, P.L. Rad18-dependent SUMOylation of human specialized DNA polymerase eta is required to prevent under-replicated DNA. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13326.

- Ryu, H.-Y.; Hochstrasser, M. Histone sumoylation and chromatin dynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 6043–6052.

- Lee, B.; Muller, M.T. SUMOylation enhances DNA methyltransferase 1 activity. Biochem. J. 2009, 421, 449–461.

- Nayak, A.; Viale-Bouroncle, S.; Morsczeck, C.; Muller, S. The SUMO-specific isopeptidase SENP3 regulates MLL1/MLL2 methyltransferase complexes and controls osteogenic differentiation. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 47–58.

- Srinivasan, S.; Shankar, S.R.; Wang, Y.; Taneja, R. SUMOylation of G9a regulates its function as an activator of myoblast proliferation. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 250.

- Liu, B.; Tahk, S.; Yee, K.M.; Fan, G.; Shuai, K. The ligase PIAS1 restricts natural regulatory T cell differentiation by epigenetic repression. Science 2010, 330, 521–525.

- Liu, B.; Tahk, S.; Yee, K.M.; Yang, R.; Yang, Y.; Mackie, R.; Hsu, C.; Chernishof, V.; O’Brien, N.; Jin, Y.; et al. PIAS1 regulates breast tumorigenesis through selective epigenetic gene silencing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89464.

- Bawa-Khalfe, T.; Cheng, J.; Lin, S.H.; Ittmann, M.M.; Yeh, E.T.H. SENP1 induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia through multiple mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25859–25866.

- Wang, Q.; Xia, N.; Li, T.; Xu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Fan, Q.; Bawa-Khalfe, T.; Yeh, E.T.H.; Cheng, J. SUMO-specific protease 1 promotes prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Oncogene 2013, 32, 2493–2498.

- Castillo-Lluva, S.; Tatham, M.H.; Jones, R.C.; Jaffray, E.G.; Edmondson, R.D.; Hay, R.T.; Malliri, A. SUMOylation of the GTPase Rac1 is required for optimal cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 1078–1085.

- Li, C.; McManus, F.P.; Plutoni, C.; Pascariu, C.M.; Nelson, T.; Alberici Delsin, L.E.; Emery, G.; Thibault, P. Quantitative SUMO proteomics identifies PIAS1 substrates involved in cell migration and motility. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 834.

- Long, J.; Matsuura, I.; He, D.; Wang, G.; Shuai, K.; Liu, F. Repression of Smad transcriptional activity by PIASy, an inhibitor of activated STAT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 9791–9796.

- Chandhoke, A.S.; Karve, K.; Dadakhujaev, S.; Netherton, S.; Deng, L.; Bonni, S. The ubiquitin ligase Smurf2 suppresses TGFβ-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a sumoylation-regulated manner. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 876–888.

- Jang, D.; Kwon, H.; Choi, M.; Lee, J.; Pak, Y. Sumoylation of Flotillin-1 promotes EMT in metastatic prostate cancer by suppressing Snail degradation. Oncogene 2019, 38, 3248–3260.

- Chanda, A.; Ikeuchi, Y.; Karve, K.; Sarkar, A.; Chandhoke, A.S.; Deng, L.; Bonni, A.; Bonni, S. PIAS1 and TIF1γ collaborate to promote SnoN SUMOylation and suppression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 267–282.

- Jiao, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, Z.; Yin, Y.; Fang, X.; Ding, X.; Cai, Y.; Yang, S.; Mu, H.; Zong, D.; et al. Nuclear Smad6 promotes gliomagenesis by negatively regulating PIAS3-mediated STAT3 inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2504.

- Adorisio, S.; Fierabracci, A.; Muscari, I.; Liberati, A.M.; Ayroldi, E.; Migliorati, G.; Thuy, T.T.; Riccardi, C.; Delfino, D.V. SUMO proteins: Guardians of immune system. J. Autoimmun. 2017, 84, 21–28.

- Ran, Y.; Liu, T.-T.; Zhou, Q.; Li, S.; Mao, A.-P.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.-J.; Cheng, J.-K.; Shu, H.-B. SENP2 negatively regulates cellular antiviral response by deSUMOylating IRF3 and conditioning it for ubiquitination and degradation. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 3, 283–292.

- Liang, Q.; Deng, H.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Tang, Q.; Chang, T.-H.; Peng, H.; Rauscher, F.J.; Ozato, K.; Zhu, F. Tripartite Motif-Containing Protein 28 Is a Small Ubiquitin-Related Modifier E3 Ligase and Negative Regulator of IFN Regulatory Factor 7. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 4754–4763.

- Kubota, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Xu, S.; Otsuki, N.; Takeda, M.; Kato, A.; Ozato, K. PIASy inhibits virus-induced and interferon-stimulated transcription through distinct mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 8165–8175.

- Chang, T.-H.; Xu, S.; Tailor, P.; Kanno, T.; Ozato, K. The Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier-Deconjugating Enzyme Sentrin-Specific Peptidase 1 Switches IFN Regulatory Factor 8 from a Repressor to an Activator during Macrophage Activation. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 3548–3556.

- Kubota, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Chang, T.H.; Tailor, P.; Sasaki, T.; Tashiro, M.; Kato, A.; Ozato, K. Virus infection triggers SUMOylation of IRF3 and IRF7, leading to the negative regulation of type I interferon gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 25660–25670.

- Hu, M.M.; Yang, Q.; Xie, X.Q.; Liao, C.Y.; Lin, H.; Liu, T.T.; Yin, L.; Shu, H.B. Sumoylation Promotes the Stability of the DNA Sensor cGAS and the Adaptor STING to Regulate the Kinetics of Response to DNA Virus. Immunity 2016, 45, 555–569.

- Cui, Y.; Yu, H.; Zheng, X.; Peng, R.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Qu, B.; Shen, N.; et al. SENP7 Potentiates cGAS Activation by Relieving SUMO-Mediated Inhibition of Cytosolic DNA Sensing. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006156.

- Desterro, J.M.P.; Rodriguez, M.S.; Hay, R.T. SUMO-1 modification of IκBα inhibits NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell 1998, 2, 233–239.

- Huang, T.T.; Wuerzberger-Davis, S.M.; Wu, Z.H.; Miyamoto, S. Sequential Modification of NEMO/IKKγ by SUMO-1 and Ubiquitin Mediates NF-κB Activation by Genotoxic Stress. Cell 2003, 115, 565–576.

- Zhao, T.; Yang, L.; Sun, Q.; Arguello, M.; Ballard, D.W.; Hiscott, J.; Lin, R. The NEMO adaptor bridges the nuclear factor-κB and interferon regulatory factor signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 592–600.

- Liu, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, C. Negative Regulation of TLR Inflammatory Signaling by the SUMO-deconjugating Enzyme SENP6. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003480.

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, W.; Wang, C. Dynamic regulation of innate immunity by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 559–570.

- Yu, X.; Lao, Y.; Teng, X.L.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Guo, X.; Deng, S.; Chang, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. SENP3 maintains the stability and function of regulatory T cells via BACH2 deSUMOylation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3157.

- Xiao, M.; Bian, Q.; Lao, Y.; Yi, J.; Sun, X.; Sun, X.; Yang, J. SENP3 loss promotes M2 macrophage polarization and breast cancer progression. Mol. Oncol. 2021.

- Hu, Z.; Teng, X.L.; Zhang, T.; Yu, X.; Ding, R.; Yi, J.; Deng, L.; Wang, Z.; Zou, Q. SENP3 senses oxidative stress to facilitate STING-dependent dendritic cell antitumor function. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 940–952.e5.

- Decque, A.; Joffre, O.; Magalhaes, J.G.; Cossec, J.C.; Blecher-Gonen, R.; Lapaquette, P.; Silvin, A.; Manel, N.; Joubert, P.E.; Seeler, J.S.; et al. Sumoylation coordinates the repression of inflammatory and anti-viral gene-expression programs during innate sensing. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 140–149.

- Crowl, J.T.; Stetson, D.B. SUMO2 and SUMO3 redundantly prevent a noncanonical type I interferon response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6798–6803.