| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amélia Martins Delgado | + 2304 word(s) | 2304 | 2021-08-27 09:40:14 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 2304 | 2021-09-13 05:24:20 | | |

Video Upload Options

Food databases (FDB), or more correctly food composition databases, contain detailed information on the nutritional composition of foods and on other relevant compounds (e.g., polyphenols, phytic acid). Food components primarily determine nutritional features and, in some cases, quality aspects. For example, polyphenols, which are abundant in plants, are often associated to bitter taste and astringency sensation of foods, while acting in favour of food safety by inhibiting foodborne pathogens and spoilage microbes.

1. Introduction

Food databases (FDB), or more correctly food composition databases, contain detailed information on the nutritional composition of foods and on other relevant compounds (e.g., polyphenols, phytic acid). Food components primarily determine nutritional features and, in some cases, quality aspects. For example, polyphenols, which are abundant in plants, are often associated to bitter taste and astringency sensation of foods [1], while acting in favour of food safety by inhibiting foodborne pathogens and spoilage microbes. Polyphenols can be intentionally added to foods for their bioactive properties [2][3][4] or they can be key natural components, as happens in table olive fermentation [5][6]. During the spontaneous fermentation process, olive’s polyphenols help to select the suitable microbial populations, resulting in taster and safer foodstuffs.

Today, food system sustainability is questioned to better address the SDGs, as are consumers’ dietary shifts driven by environmental concerns [7]. The interconnection between public health and environmental issues is more and more acknowledged and translated into action [8], while FDBs’ gaps have been noticed at the level of the environment-public health nexus [9]. Moreover, the strategic trend of using food by-products as ingredients in other foods (secondary raw materials) seems to be insufficiently addressed by existing FDB. The importance of FDBs is such that inaccurate food composition data can result in incorrect policies (regarding nutritional guidelines and the agri-food system), misleading food labelling, incorrect health claims, and inadequate food choices by the consumers, especially concerning industrially processed foods with added salt, fats, and/or sugars. Therefore, the awareness of relevant new trends and the adjustments to address them is as important as the frequency of FDB’s data update.

A comprehensive review on the production, management, and use of food composition data was released by the FAO (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization) in 2003 [10], dedicating one chapter to possible limitations of FDB. However, the nexus between food, health, and the environment was not considered because there was little or no awareness yet about it, since the agreement on 2030 agenda only took place in 2015 [11].

According to the FAO [10][12], the three pillars of FDBs should be: (a) the existence of international standards and guidelines for food composition data; (b) national and/or regional programs supporting the regular update of FDB; (c) professional training in aspects related to food composition. In order to ensure these foundations, InFoods (International Network of Food Data Systems) was established in 1984. This FDB is based in regional nodes, under a global coordination, and acts as a network of experts and as a taskforce to respond to users’ needs, database content, organization, and operation, etc. InFoods keep standards in food nomenclature, terminology, and classification systems, in food component identifiers (tag names), in exchange of data between FDB, and in data quality [12]. In addition to its role in setting standards, the FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius also keeps specific databases, notably on pesticides residues in food and on veterinary drug residues in food [13].

2. Current Uses, State-of-the-Art, and Future Challenges of Food Composition Databases

Connections between FDBs complement information about a certain food or about the food sources for a certain compound; for example, bioactive compounds are included in the eBASIS database, in the US isoflavone database and in the French Phenol-Explorer database, all linked to EuroFIR and to FoodData central, as detailed below.

FDBs’ interlinkage adheres to agreed international standards and guidelines, which are of the competence of InFOODs, the International Network of Food Data System from the FAO (UN, Food and Agriculture Organization). It acts as a network of regional datacentres with a central coordination, as well as a forum for the international harmonization and support for food composition activities. InFOODs aims at linking agriculture, biodiversity, food systems, health, and nutrition to achieve better nutrition worldwide. The network regularly issues publications on food composition and other food-related aspects, and its webpage provides access to searchable FDBs [12].

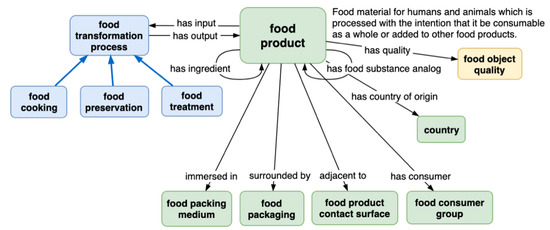

The standardization and harmonizing of food composition data from different countries with distinct metadata are essential to ensure efficient data linkage and the retrieval of information. Hence, tools and procedures have been developed aiming to guarantee interoperability between the databases. Langual is such a tool [14]. It is a food description thesaurus that stands for ‘langua alimentaria’ or ‘language of food’ and provides a standardised language for describing foods, specifically in classifying food products for information retrieval. Each of their over 40,000 foods is described by the means of numerical attributes on food composition (nutrients and contaminants), food consumption, and legislation. Langual establishes a correspondence between these food attributes (descriptors) and common language terms in different natural languages [14]. This important tool facilitates the linkage to many different food data banks from different countries, interpreting distinct designations and resolving ambiguities to ensure the correspondence between food and their attributes, thus contributing to coherent data exchange [15]. The food indexing system of Langual already considers food source (e.g., animal or plant species), food preservation (e.g., fresh, frozen), cooking, packaging, etc. However, the next generation of this European FDB thesaurus is even more complex and comprehensive. This global initiative under development—FoodOn—deals with a very comprehensive semantics encompassing descriptors for food safety, food security, agricultural practices, culinary, nutritional and chemical ingredients, and processes [14][15], as can be overviewed in Figure 1 .

Experimental science advances are based in data, including from FDB, and such figures are commonly fed into models, producing results from which conclusions are withdrawn. Nowadays, these processes can be easily automated by using a bot/API to download data from FDB, which can then be analysed with the assistance of an AI, allowing for instance rapid identification of patterns and trends. With more or less automation, the ability to provide reliable and significant results rely on the research’s rigor and methodologies, as much as on the rigor and detail of the semantics and structure of the database from where the information was withdrawn. Specially developed apps may provide insights on more obvious relationships (e.g., between dietary intakes and health) or less obvious relationships (as between food composition and climate change). So, besides the traditional use in assessing nutrient intakes for diet planning, FDBs can have many more applications for different users in the food value chain, facilitated by IT tools that make it easier to manage and analyse large quantities of data and information. FDBs can, thus, be important tools for exploring the relationship between foods, diets, and nutrients’ intake, regarding nutritional needs and micronutrient deficiencies; yet, a need to better categorise bioactive compounds in foods is emerging, as state-of-the-art knowledge has been disclosing more and more compounds from foods with important physiological roles. Another emerging trend relates to the environmental impact of foods and attempts in systematizing available information are mentioned below (see Section 4.7.3 ). The key nutritional components found in FDBs are only a few among the more than 26,000 distinct, definable biochemicals present in our food that remain unquantified [16].

3. Main Whole Food Composition Databases

This FDB supplies extensive data on food constituents, chemistry, and biology, providing information on both macronutrients and micronutrients, including many of the constituents that give foods their flavour, colour, taste, texture, and aroma with detailed compositional, biochemical, and physiological information (obtained from the literature). Searches can be made by food source, name, function, or concentrations, and the FDB content can be accessed from the Food Browse (listing foods by their chemical composition) or from the Compound Browse (listing chemicals by their food sources), according to the user’s preferences. A section called ‘reports’ is noteworthy, since it concerns monographies of a list of foods featuring composition and nutritional and health benefits, based on scientific literature review [17].

The FDBs listed in Table 1 follow international standards and are interconnected thus providing access to reliable, comprehensive information on foods serving most common purposes.

| Organization | Name of FDB | URL (Available at the Bate of the Current Publication) |

Discrimination of Food Composition | Source of Data | Ease of Access | Regularity of Updates | Citation/Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USDA | FoodData Central | https://fdc.nal.usda.gov accessed on 17 August 2021; | Target important components that make sense in each food; highly discriminated | Laboratory analysis by state-of-the-art methods | Search by food name or by component + API for access with proprietary app; instructions and tips provided | Regularly updated (date is shown) | U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central: Version October 2020.: |

| TMIC | FoodB | www.foodb.ca accessed on 17 August 2021 | Content range and average values for an extensive list of compounds | Literature and other FDB | Search by food name or browse foods by constituents | Frequency of updates not mentioned (last update in 2021) | www.foodb.ca accessed on 17 August 2021 |

| DTU food (National food Institute (Denmark) | Fødevaredata (Frida Food Data) | http://frida.fooddata.dk/ accessed on 17 August 2021 | DTU foods’ database—Frida Food Data reflects the food supply in Denmark and targets professionals in food and nutrition | Laboratory analysis | Easily searched by food item (alphabetic order), food group or by parameters, which include waste and added sugar | Updated every few years (last update 29/10/19) and food composition referred to be quite stable over the past 50 years | Food data (frida.fooddata.dk accessed on 17 August 2021), version 4, 2019, National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark |

| EuroFIR AISBL, International non-profit association | EuroFIR | https://www.eurofir.org/food-information/ accessed on 17 August 2021 | The dataset presents energy, macronutrients, vitamins, and minerals as well as other bioactive compounds and daily recommended intakes for selected nutrients | Estimations from FDB by expert panels and targets food and nutrition professionals | Search by food name and by component | Updated regularly (each few years)—last update 21 January | European Food Safety Authority (2013) ‘Food composition database for nutrient intake: selected vitamins and minerals in selected European countries’. Zenodo. doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.438313. |

| FAO | InFoods | http://www.fao.org/infoods/infoods/en/ accessed on 17 August 2021 | InFoods is a network bringing together food composition compilers, data generators (e.g., chemists), and data users (e.g., nutritionists, food scientists), and decision makers | food composition database compilers retrieve analytical data on food composition for commonly consumed foods and complemented with other published sources | Datasets are downloadable in xls and pdf formats, as well as searchable with software tools for e.g., dietary assessment, labeling and food supply/availability data | Updated regularly | FAO. 2020. International Network of Food Data Systems (InFoods) |

| CIQUAL-ANSES | French Food Composition Database | https://ciqual.anses.fr/ accessed on 17 August 2021 | Average nutritional composition of food consumed in France. Average value of each component, a minimum and a maximum, together with a confidence code (A = very reliable, D = less reliable). Information on a specific component (ex. list of food rich in calcium or poor in sodium) |

Compilation of different sources: yearly sampling of around 60 to 80 foods in collaboration with subcontractor laboratory; data from OQALI; research programmes on food composition with external partners. Scientific literature and laboratory reports; foreign food composition tables | Easily searched by food item, food group, or by components | Released every 2 to 4 years | French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety. ANSES-CIQUAL French food composition table version 2020. |

Similarly, the Turkish food composition database, an open access digital platform, ‘Türkomp’ ( http://www.turkomp.gov.tr/main accessed on 17 August 2021), available online at the date of this publication provides a considerable dataset and information related to the nutrients, composition, and energy values of processed or unprocessed agricultural products that are produced and consumed in Turkey. Türkomp exhibits 63,000 data entries on the nutritional and energy value of 100 food components belonging to 580 foods from 14 food groups [18].

Edamam also provide data for basic foods (as flour and eggs) for calories, fats, carbohydrates, protein, cholesterol, sodium, etc., for a total of 28 nutrients.

4. Emerging Applications and Trends of Food Databases

In view of the ongoing changes in food systems, needs for curated and organized information on the composition of food secondary raw-materials, novel foods, and/or sources for nutrients (as insects and microalgae) are expected to be met by FDBs. These challenges may exacerbate existing issues with food data composition. Thus, in addition to the intrinsic features of foods, parameters related to the extraction and analytical procedures should be considered, according to Durazzo et al., [19], as different extraction procedures and analytical techniques and methodologies may lead to different datasets. Moreover, still according to these authors, only a few compounds within a class are investigated, and there are knowledge gaps on appropriate analytical methods for food analysis. The acknowledged complexity of foods (in their multiple dimensions) calls for information on multiple relationships, as the nexus between public health and the environment, or consumer preference and health [20][21][22][23]. Ocké et al. [9], besides identifying some gaps herein mentioned, also refer to the need for FDBs’ adaptation to the rapidly changing food landscape and the need for their improvement and harmonization to enable comparisons of research outputs at international level. More generally, in the near future, there is, therefore, an important need for more comprehensive and holistic FDB, not only addressing nutritional composition, but also other food properties. In this way, FDBs will, thus, constitute more robust tools for tackling global health, but this means a huge scientific work to gather all data, notably when thousands of new industrially processed foods are marketed each year worldwide.

References

- Issaoui, M.; Delgado, A.M.; Caruso, G.; Micali, M.; Barbera, M.; Atrous, H.; Ouslati, A.; Chammem, N. Phenols, Flavors, and the Mediterranean Diet. J. AOAC Int. 2020, 103, 915–924.

- Gan, Z.; Wei, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T.; Zhong, X. Curcumin and Resveratrol Regulate Intestinal Bacteria and Alleviate Intestinal Inflammation in Weaned Piglets. Molecules 2019, 24, 1220.

- Tsukamoto, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Uwai, K.; Taguchi, R.; Chayama, K.; Sakaguchi, T.; Narita, R.; Yao, W.L.; Takeuchi, F.; Otakaki, Y.; et al. Rosmarinic acid is a novel inhibitor for Hepatitis B virus replication targeting viral epsilon RNA-polymerase interaction. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197664.

- Vieira, F.N.; Lourenço, S.; Fidalgo, L.G.; Santos, S.; Silvestre, A.; Jerónimo, E.; Saraiva, J.A. Long-Term Effect on Bioactive Components and Antioxidant Activity of Thermal and High-Pressure Pasteurization of Orange Juice. Molecules 2018, 23, 2706.

- Amini, A.; Liu, M.; Ahmad, Z. Understanding the link between antimicrobial properties of dietary olive phenolics and bacterial ATP synthase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 153–164.

- Delgado, A.; Arroyo López, F.N.; Brito, D.; Peres, C.; Fevereiro, P.; Garrido-Fernández, A. Optimum bacteriocin production by Lactobacillus plantarum 17.2b requires absence of NaCl and apparently follows a mixed metabolite kinetics. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 130, 193–201.

- From Science to Practice: Research and Knowledge to Achieve the SDGs. Policy Brief 38|July 2021, UNRIDS, Geneve, Switzerland. Available online: www.unrisd.org/rpb38 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Dupraz, J.; Burnand, B. Role of Health Professionals Regarding the Impact of Climate Change on Health—An Exploratory Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3222.

- Ocké, M.C.; Westenbrink, S.; van Rossum, C.T.M.; Temme, E.H.M.; van der Vossen-Wijmenga, W.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J. The essential role of food composition databases for public health nutrition–Experiences from the Netherlands. J. Food Compost. Anal. 2021, 101, 103967.

- Greenfield, H.; Southgate, D.A.T. Food Composition Data: Production, Management and Use, 2nd ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003.

- UN, Sustainable Development Goals, News, Sustainable Development Agenda, 24 September 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2015/09/summit-charts-new-era-of-sustainable-development-world-leaders-to-gavel-universal-agenda-to-transform-our-world-for-people-and-planet/ (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO. International Network of Food Data Systems (INFOODS). Available online: http://www.fao.org/infoods/infoods/en/ (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- FAO/WHO. Codex Alimentarius, International Food Standards. Codex Online Databases. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/dbs/en/ (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Langual. The International Framework for Food Description, Danish Food Informatics. 2017. Available online: https://www.langual.org/default.asp (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Møller, A.; Ireland, J. LanguaL™ 2017-Multilingual Thesaurus (English–Czech–Danish–French–German–Italian–Portuguese–Spanish); Technical Report Danish Food Informatics; Danish Food Informatics: Roskilde, Danmark, 2018.

- Barabási, A.L.; Menichetti, G.; Loscalzo, J. The unmapped chemical complexity of our diet. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 33–37.

- FoodDB Version 1.0. 2021. Available online: www.foodb.ca (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Turkish Food Composition Database. Available online: http://www.turkomp.gov.tr/main (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Durazzo, A.; Nazhand, A.; Lucarini, M.; Delgado, A.M.; De Wit, M.; Nyam, K.L.; Santini, A.; Ramadan, M.F. Occurrence of Tocols in Foods: An Updated Shot of Current Databases. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 1–7.

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Bartkiene, E.; Florença, S.G.; Djekić, I.; Bizjak, M.Č.; Tarcea, M.; Leal, M.; Ferreira, V.; Rumbak, I.; Orfanos, P.; et al. Environmental Issues as Drivers for Food Choice: Study from a Multinational Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2869.

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19. Sustainable Development Report 2020; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020.

- Średnicka-Tober, D.; Kazimierczak, R.; Rembialkowska, E. Organic food and human health—A review. J. Res Appl. Agric. Eng. 2015, 60, 102–107.

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E. How to protect both health and food system sustainability? A holistic ‘global health’-based approach via the 3V rule proposal. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 3028–3044.