Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Konstantinos Kapetanos | + 1628 word(s) | 1628 | 2021-08-09 08:58:11 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1628 | 2021-09-02 05:50:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kapetanos, K. MSC Senescence. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/13810 (accessed on 07 March 2026).

Kapetanos K. MSC Senescence. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/13810. Accessed March 07, 2026.

Kapetanos, Konstantinos. "MSC Senescence" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/13810 (accessed March 07, 2026).

Kapetanos, K. (2021, September 01). MSC Senescence. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/13810

Kapetanos, Konstantinos. "MSC Senescence." Encyclopedia. Web. 01 September, 2021.

Copy Citation

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are a heterogeneous population of stromal cells capable of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation into various tissues of mesodermal origin.

mesenchymal stromal cells

senescence

ageing

biomarkers

systematic review

human

1. Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are a heterogeneous population of stromal cells capable of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation into various tissues of mesodermal origin [1]. Although MSCs were originally isolated from bone marrow [2], recent research has identified alternative sources, including adipose tissue [3], dental pulp [4], the endometrium [5], peripheral blood [6], the periodontal ligament [7], the placenta [8], the synovial membrane [9], and umbilical cord blood [10]. Evidence has suggested that MSCs can be found in all vascularized tissues of the body [11]. MSCs have a high proliferative potential, multipotency, immunomodulatory activity, and paracrine effect [12][13][14]. These features, as well as the lack of ethical concerns that surround embryonic stem cells, make MSCs a promising material for cell therapy, regenerative medicine, immune modulation, and tissue engineering [15]. In the last decade, they have been increasingly used in clinical practice to treat numerous traumatic and degenerative disorders [16].

Although there is no consensus on a single surface molecule to identify MSCs, the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) proposed a minimum of three criteria that need to be satisfied for a cell to be considered an MSC [17]: (a) adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; (b) expression of CD73, CD90, and CD105, and lack of expression of CD11b or CD14, CD34, CD45, CD19 or CD79a, and HLA-DR; (c) differentiation into adipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts in vitro. Other surface markers generally expressed by MSCs include CD10, CD13, CD29, and CD44 [18][19].

Although MSCs are present in several tissues, their numbers are low within the aspirate. Thus, to be clinically useful, MSCs need to be expanded in vitro over several population doublings (PDs) to obtain enough cells before implantation. The chronological age of a donor strongly influences the quality and lifespan of MSCs [20][21]; MSCs from aged donors perform less well than their younger counterparts because of their reduced proliferative capacity and differentiation potential [22]. Additionally, their regenerative potential declines after 30 years of age [23]. This is further supported by the observation that human umbilical cord MSCs, being neonatal in origin, can grow up to passage 10 without losing multipotential capacity [24], and exhibit enhanced expression of telomerase and pluripotency factors compared to adult bone marrow-derived MSCs [25].

While in vivo ageing refers to the chronological age of the donor, which affects the lifespan of MSCs, in vitro ageing is the loss of MSC characteristics as they acquire a senescent phenotype during expansion in culture. Irrespective of donor age, during in vitro expansion, the proliferation rate progressively decreases until growth arrests [26][27][28][29]. This was first proposed by Hayflick in 1965, who suggested that all primary cells cease to proliferate after a certain number of cell divisions in a process known as cellular senescence [30]. Senescence negatively affects the differentiation capacities of MSCs, resulting in reduced efficacy following transplantation [31]. Several biological markers have been proposed to drive senescence. These include p16, p21, p53, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) [32][33]. They take part in several biochemical pathways of the cell cycle. Other markers, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), are found to inhibit the cell from reaching that state [34]. The levels of the aforementioned markers differ as the MSCs undergo chronological ageing.

2. Specifics

While in vivo ageing refers to the chronological age of the donor, in vitro ageing is the loss of MSC characteristics as they acquire a senescent phenotype during in vitro expansion. For MSCs to be clinically effective in an ageing population, it would be of great significance to monitor senescence and understand the molecular basis of chronological ageing.

The diverse nature of MSCs poses a great challenge to forming a precise characterisation profile [35]. The minimal criteria to define MSCs, as proposed by the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) [17], were an important step towards the standardisation of MSC models. However, it is yet unclear whether these criteria are accurate, essential, and comprehensive. Several of the studies included in this review described an MSC population that included some, but not all, of the minimal criteria [32][33][34][36][37][38][39][40]. The heterogeneity between MSC populations in different studies prevents the accurate comparison of outcomes. This poses a particular challenge to the advancement of the field. A potential solution would be to rely on functional assays, as well as surface marker characterisation, to accurately define an MSC population. This could involve differentiation potentials [17] and immunological characterisation [41].

2.1. Senescence

Senescence is a concept with an elusive definition. Broadly, it describes cellular deterioration due to ageing, and a subsequent loss of growth and proliferative capacity. Senescence is a well-documented outcome in cellular populations that undergo genotoxic stress [42]. This is reflected in a cell’s absence of proliferation, the expression of senescence markers, and the secretion of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). It is an irreversible state that protects a cell from the consequences of compromised genomic integrity [43]. However, there is no single phenotypic definition to describe the process of senescence, but rather a collection of phenotypes. Specifically, hallmarks of cellular senescence include an arrest of the cell cycle, resistance to apoptosis, SA-β-gal expression, and a SASP that is associated with growth-related oncogene (GRO), IL-8, IL-12, and macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC) [44]. The driving cause of senescence with ageing appears to be telomere dysfunction, as well as associated genetic and epigenetic changes, perceived as DNA damage and activating the persistent DNA damage response (pDDR) mechanism [45][46]. Human MSCs have been described as exhibiting a marked resistance to apoptosis and to default to a senescence phenotype in response to injury [31]. When exposed to ionising radiation, p53 and p21 were seen to drive MSC cycle arrest and p16 and RB to drive senescence [47]. Similar markers were explored by some of the studies included in this review, with SA-β-gal, inflammatory markers, and pDDR proteins being most frequently referenced [32][33][34][36][39]. A reduction in the rates of proliferation, as well as an increase in the senescence phenotype was observed in similar experiments that evaluate the effects of in vitro ageing on MSCs [48].

2.2. Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis

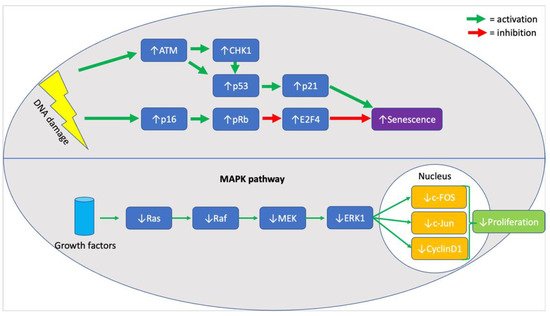

When assessing the effects of chronological age on MSC senescence it is essential to evaluate evidence for cell cycle arrest and against proliferation. In the included studies, p21 and p53 were seen to be significantly upregulated in six studies [32][34][49][36][39][40], providing strong evidence for cell cycle arrest, as both molecules are central components of the response pathway to DNA damage [50]. In addition, upregulation of p16 [32][36][39], ATM [36], CHK1 [36], E2F4 [36], and RB [36] (illustrated in Figure 1, below) was also noted in MSC samples from older donors, highlighting the persistent activation of the DNA damage response pathway [51]. Although the upregulation of all mentioned markers was rarely seen in a single study, the six studies mentioned the upregulation of at least one marker, with the remaining three not mentioning whether they looked for a change in their expression. Furthermore, highlighting the effects of an activated pDDR in cells from older donors, a decrease in the expression of proliferative markers like Ki67, MAPK pathway (illustrated in Figure 1, below) elements, and Wnt/β-catenin pathway elements was seen in two studies [33][49]. It is unclear, however, whether the absence of proliferation was associated with an increase in the rate of apoptosis. It is known that MSCs exhibit resistance to apoptosis [17], and so do most senescent cells, but the evidence in the literature was contradicting. Specifically, both mention that an increase in the rate of apoptosis [34] and a decrease in the expression of caspases 3/8/9 [36] was seen in two different studies. Two studies reported an increase in the expression of SA-β-galactosidase, supporting the association between senescence and chronological age [32][40].

Figure 1. Summary of molecular markers implicated in the senescence phenotype of aged MSCs.

2.3. Stress and Inflammation

In line with the evidence provided for the activation of stress-response pathways, there was evidence of an increase in stressful agents in older donors. An increase in the quantified levels of ROS [32][34][40], NO [34][49][40], and advanced glycosylation end-products and their receptors (AGEs and RAGEs) [34] was reported, as well as a decrease in the levels of SOD [34][39][40]. In line with an increase in markers of stress, there was an increase in the expression of inflammatory markers amongst the older donor group. Specifically, there was a reported increase in NF-κB [33][36], as well as TNFα [36] and IL-6 [49]. A potential approach to subsequent studies could be the investigation of any functional consequences on the immunological environment of MSCs from older donors, with over-expressed inflammatory markers. Lastly, there is contradicting evidence on the expression of potency markers in MSCs from older donors. Siegel et al. 2013 provided evidence that there is no difference in the expression of Oct4, Sox2, or Nanog between the two groups [38], however, Ferretti et al. (2015) suggest an increase in the expression of Nanog and Sox2, and a decrease in Oct4, in the group of older donor MSCs [49]. Further investigations into the effect of chronological age and MSC potency are crucial to provide a deeper understanding of a potential mechanism of age-induced senescence in MSCs.

2.4. Strengths and Limitations

The systematic approach to constructing a research question yielded a thorough review of the literature to identify all relevant studies. The ability to make effective comparisons between the studies was, however, limited by the heterogeneity of the included studies in defining the MSC population; not all studies followed the minimal defining criteria proposed by ISCT to define their cell population. There was a large variation in the markers explored by the different studies with most studies not investigating the effect of chronological age on the SASP or the differentiation potential of MSC, both defined hallmarks of senescence [44]. The included genetic studies offered a descriptive assessment of genes that were up- and downregulated without any implications on how these genes affect senescence pathways. Further work is needed to identify the relevant pathways through which chronological age influences senescence in MSCs.

References

- Neri, S. Genetic Stability of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Regenerative Medicine Applications: A Fundamental Biosafety Aspect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2406.

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Petrakova, K.V.; Kurolesova, A.I.; Frolova, G.P. Heterotopic transplants of bone marrow. Transplantation 1968, 6, 230–247.

- Zuk, P.A.; Zhu, M.; Ashjian, P.; De Ugarte, D.; Huang, J.; Mizuno, H.; Alfonso, Z.; Fraser, J.; Benhaim, P.; Hedrick, M. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 4279–4295.

- Gronthos, S.; Brahim, J.; Li, W.; Fisher, L.W.; Cherman, N.; Boyde, A.; DenBesten, P.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. Stem Cell Properties of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. J. Dent. Res. 2002, 81, 531–535.

- Schwab, K.E.; Hutchinson, P.; Gargett, C.E. Identification of surface markers for prospective isolation of human endometrial stromal colony-forming cells. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2008, 23, 934–943.

- Tondreau, T.; Meuleman, N.; Delforge, A.; Dejeneffe, M.; Leroy, R.; Massy, M.; Mortier, C.; Bron, D.; Lagneaux, L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from CD133-Positive Cells in Mobilized Peripheral Blood and Cord Blood: Proliferation, Oct4 Expression, and Plasticity. Stem Cells 2005, 23, 1105–1112.

- Park, J.-C.; Kim, J.-M.; Jung, I.-H.; Kim, J.C.; Choi, S.-H.; Cho, K.S.; Kim, C.-S. Isolation and characterization of human periodontal ligament (PDL) stem cells (PDLSCs) from the inflamed PDL tissue: In vitro and in vivo evaluations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 721–731.

- Fukuchi, Y.; Nakajima, H.; Sugiyama, D.; Hirose, I.; Kitamura, T.; Tsuji, K. Human Placenta-Derived Cells Have Mesenchymal Stem/Progenitor Cell Potential. Stem Cells 2004, 22, 649–658.

- Gómez, T.H.; Boquete, I.M.F.; Gimeno-Longas, M.J.; Muiños-López, E.; Prado, S.D.; De Toro, F.J.; Blanco, F.J. Quantification of Cells Expressing Mesenchymal Stem Cell Markers in Healthy and Osteoarthritic Synovial Membranes. J. Rheumatol. 2010, 38, 339–349.

- Wang, H.-S.; Hung, S.-C.; Peng, S.-T.; Huang, C.-C.; Wei, H.-M.; Guo, Y.-J.; Fu, Y.-S.; Lai, M.-C.; Chen, C.-C. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Wharton’s Jelly of the Human Umbilical Cord. Stem Cells 2004, 22, 1330–1337.

- Crisan, M.; Yap, S.; Casteilla, L.; Chen, W.C.; Corselli, M.; Park, T.S.; Andriolo, G.; Sun, B.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, L.; et al. A Perivascular Origin for Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Multiple Human Organs. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 3, 301–313.

- Sharma, R.R.; Pollock, K.; Hubel, A.; McKenna, D. Mesenchymal stem or stromal cells: A review of clinical applications and manufacturing practices. Transfusion 2014, 54, 1418–1437.

- Aronin, C.E.P.; Tuan, R.S. Therapeutic potential of the immunomodulatory activities of adult mesenchymal stem cells. Birth Defects Res. Part C Embryo Today Rev. 2010, 90, 67–74.

- Gebler, A.; Zabel, O.; Seliger, B. The immunomodulatory capacity of mesenchymal stem cells. Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 128–134.

- English, K. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stromal cell immunomodulation. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2013, 91, 19–26.

- Wei, X.; Yang, X.; Han, Z.-P.; Qu, F.-F.; Shao, L.; Shi, Y.-F. Mesenchymal stem cells: A new trend for cell therapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 747–754.

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317.

- Bühring, H.; Battula, V.L.; Treml, S.; Schewe, B.; Kanz, L.; Vogel, W. Novel Markers for the Prospective Isolation of Human MSC. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1106, 262–271.

- Jones, E.A.; Kinsey, S.E.; English, A.; Jones, R.A.; Straszynski, L.; Meredith, D.M.; Markham, A.F.; Jack, A.; Emery, P.; McGonagle, D. Isolation and characterization of bone marrow multipotential mesenchymal progenitor cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 3349–3360.

- Sotiropoulou, P.A.; Perez, S.A.; Salagianni, M.; Baxevanis, C.N.; Papamichail, M. Characterization of the Optimal Culture Conditions for Clinical Scale Production of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2006, 24, 462–471.

- Duggal, S.; Brinchmann, J.E. Importance of serum source for the in vitro replicative senescence of human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226, 2908–2915.

- Baker, N.; Boyette, L.B.; Tuan, R.S. Characterization of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in aging. Bone 2015, 70, 37–47.

- Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal stem cells: Cell-based reconstructive therapy in orthopedics. Tissue Eng. 2005, 11, 1198–1211.

- Sarugaser, R.; Hanoun, L.; Keating, A.; Stanford, W.L.; Davies, J.E. Human mesenchymal stem cells self-renew and differentiate according to a deterministic hierarchy. PLoS ONE 2009, 4.

- Yannarelli, G.; Pacienza, N.; Cuniberti, L.; Medin, J.; Davies, J.; Keating, A. Brief Report: The Potential Role of Epigenetics on Multipotent Cell Differentiation Capacity of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Stem Cells 2012, 31, 215–220.

- Banfi, A.; Muraglia, A.; Dozin, B.; Mastrogiacomo, M.; Cancedda, R.; Quarto, R. Proliferation kinetics and differentiation potential of ex vivo expanded human bone marrow stromal cells: Implications for their use in cell therapy. Exp. Hematol. 2000, 28, 707–715.

- Sethe, S.; Scutt, A.; Stolzing, A. Aging of mesenchymal stem cells. Ageing Res. Rev. 2006, 5, 91–116.

- Noer, A.; Boquest, A.C.; Collas, P. Dynamics of adipogenic promoter DNA methylation during clonal culture of human adipose stem cells to senescence. BMC Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 18.

- Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Bu, H.; Bao, J. Senescence of mesenchymal stem cells (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 775–782.

- Hayflick, L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1965, 37, 614–636.

- Turinetto, V.; Vitale, E.; Giachino, C. Senescence in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Functional Changes and Implications in Stem Cell-Based Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1164.

- Liu, M.; Lei, H.; Dong, P.; Fu, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ma, J.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, R. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells from the elderly exhibit decreased migration and differentiation abilities with senescent properties. Cell Transplant. 2017, 26, 1505–1519.

- Pandey, A.; Semon, J.; Kaushal, D.; O’Sullivan, R.; Glowacki, J.; Gimble, J.; Bunnell, B. MicroRNA profiling reveals age-dependent differential expression of nuclear factor κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase in adipose and bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2011, 2, 49.

- Stolzing, A.; Jones, E.; McGonagle, D.; Scutt, A. Age-related changes in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Consequences for cell therapies. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008, 129, 163–173.

- Karp, J.M.; Teo, G.S.L. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Homing: The Devil Is in the Details. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 206–216.

- Alt, E.U.; Senst, C.; Murthy, S.N.; Slakey, D.P.; Dupin, C.L.; Chaffin, A.E.; Kadowitz, P.J.; Izadpanah, R. Aging alters tissue resident mesenchymal stem cell properties. Stem Cell Res. 2012, 8, 215–225.

- Wagner, W.; Bork, S.; Horn, P.; Krunic, D.; Walenda, T.; Diehlmann, A.; Benes, V.; Blake, J.; Huber, F.-X.; Eckstein, V.; et al. Aging and Replicative Senescence Have Related Effects on Human Stem and Progenitor Cells. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5846.

- Siegel, G.; Kluba, T.; Hermanutz-Klein, U.; Bieback, K.; Northoff, H.; Schäfer, R. Phenotype, donor age and gender affect function of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 146.

- Choudhery, M.S.; Badowski, M.; Muise, A.; Pierce, J.; Harris, D.T. Donor age negatively impacts adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell expansion and differentiation. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 8.

- Marędziak, M.; Marycz, K.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Kornicka, K.; Henry, B.M. The Influence of Aging on the Regenerative Potential of Human Adipose Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 1–15.

- Krampera, M.; Galipeau, J.; Shi, Y.; Tarte, K.; Sensebe, L. Immunological characterization of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells—The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) working proposal. Cytotherapy 2013, 15, 1054–1061.

- Fan, D.N.Y.; Schmitt, C.A. Genotoxic Stress-Induced Senescence. Adv. Struct. Saf. Stud. 2019, 1896, 93–105.

- Coppé, J.-P.; Patil, C.K.; Rodier, F.; Sun, Y.; Muñoz, D.P.; Goldstein, J.N.; Nelson, P.S.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J. Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotypes Reveal Cell-Nonautonomous Functions of Oncogenic RAS and the p53 Tumor Suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e301.

- Hernandez-Segura, A.; Nehme, J.; Demaria, M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 436–453.

- Hewitt, S.L.; Chaumeil, J.; Skok, J.A. Chromosome dynamics and the regulation of V(D)J recombination. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 237, 43–54.

- Fumagalli, M.; Rossiello, F.; Clerici, M.; Barozzi, S.; Cittaro, D.; Kaplunov, J.; Bucci, G.; Dobreva, M.; Matti, V.; Beausejour, C.; et al. Telomeric DNA damage is irreparable and causes persistent DNA-damage-response activation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 355–365.

- Wang, D.; Jang, D.-J. Protein kinase CK2 regulates cytoskeletal reorganization during ionizing radiation-induced senescence of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 8200–8207.

- Yang, Y.-H.K.; Ogando, C.R.; See, C.W.; Chang, T.-Y.; Barabino, G.A. Changes in phenotype and differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells aging in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 131.

- Ferretti, C.; Lucarini, G.; Andreoni, C.; Salvolini, E.; Bianchi, N.; Vozzi, G.; Gigante, A.; Mattioli-Belmonte, M. Human Periosteal Derived Stem Cell Potential: The Impact of age. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2014, 11, 487–500.

- Kurpinski, K.; Jang, D.-J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Rydberg, B.; Chu, J.; So, J.; Wyrobek, A.; Li, S.; Wang, D. Differential Effects of X-Rays and High-Energy 56Fe Ions on Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 73, 869–877.

- Ciccia, A.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA Damage Response: Making It Safe to Play with Knives. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 179–204.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

968

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

02 Sep 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No