| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Katrin Muff | + 6768 word(s) | 6768 | 2021-08-11 14:36:11 |

Video Upload Options

Positive Impact Organizations broaden their purposes and their value creation to embrace strong sustainability, thereby contributing to economic, social, and environmental value. "Positive impact" is defined by products and services that are created with the purpose of solving societal problems. It reflects the shift from reducing an organization’s negative footprint to achieving a significant net positive impact on society and the planet.

1. Introduction

In view of the significant global challenges, this entry analyzes and suggests pragmatic solutions for organizations to transform from sustainability risk management to creating a positive impact. Positive impact is defined by products and services that are created with the purpose of solving societal problems. It reflects the shift from reducing an organization’s negative footprint to achieving a significant net positive impact on society and the planet. This entry shows that such a mindset shift is observed on the level of the leadership and the organization. This explorative, case-based research validates the Dyllick–Muff BST typology and identifies strategic differentiators of Positive Impact Organizations, including their governance, culture, external validation, and a higher purpose reflected in their products and services. This entry is translated into two tools for practitioners: the Strategic Innovation Canvas (SIC) and the Positive Impact Framework (PIF). The SIC serves as a quick assessment for organizations to get started. It consists of eight action dimensions: (1) sustainability in the organization, (2) transparency and board support, (3) leadership perspective, (4) targets and incentives, (5) societal stakeholders, (6) triple value reporting, (7) market framing, and (8) products and services. The PIF offers step-by-step guidance during the organizational transformation. The entry sketches a new field of research for both scholars and practitioners in organizational transformation towards positive impacts. It bridges business sustainability and strategy through an innovation approach. By recognizing the importance of the underlying mindset shifts, it connects the fields of organizational and personal development.

2. Differentiating Sustainability Organizations from Traditional Firms

2.1. Governance Alignment

2.2. Sustainability Culture

2.3. External Validation

2.4. Higher Purpose

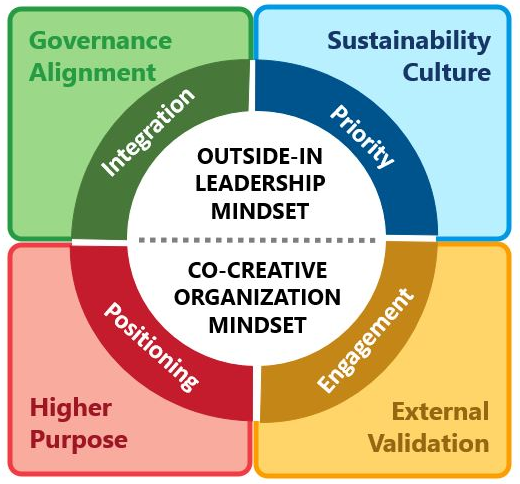

Figure 1. The strategic differentiators of Positive Impact Organizations.

Figure 1. The strategic differentiators of Positive Impact Organizations.3. The Mindsets and Practices of Positive Impact Organizations

This section translates the research into insights and tools for business practitioners.

3.1. Two Mindset Shifts as Key Predictors of Success

In its updated report, the Business Council for Sustainable Business (WBCSD) highlights that mindset shifts are an essential part of the transition. They have produced the influential “Vision 2050” report in 2010 which has gained much support. Now in 2021, they have updated the report and have provided concrete implementation suggestions [19]. One of the mindset shifts they recommend is called “Regenerative Thinking”. It suggests that business has to move beyond a “doing no harm” mindset. The WBCSD points out that it is time to unlock the potential of living systems — social and ecological — that business depends on. It is time for business to build their capacity to regenerate, thrive, and evolve.

Studying the case study organizations reveals that in order to become a Positive Impact Organization (PIO), there are two noticeable mindset shifts to be embraced. These shifts relate to the ability to shift from an inside–out to an outside–in perspective. The first mindset shift concerns the leader, or the leadership team, the second relates to how the organization operates outside of its traditional boundaries with external stakeholders. The regression analysis indicated that there are two strong predictors of success for an organization seeking to become a Positive Impact Organization. The two predictors are directly connected to the underlying mindset shifts. When comparing true sustainability organizations with early sustainability organizations, these mindsets make a significant difference:

- The outside–in leadership mindset: Leaders who “gets it” have redefined their role and the role of the organization in society. They see themselves as one with the world around them and, hence, broaden their focus to serve the common good. Such leaders derive their purpose from providing a positive contribution to society and the planet, and by aligning their organizational processes to ensure the long-term well-being of the organization;

- The co-creative organization mindset: An organization that excels in how it engages with its external stakeholders is externally oriented and open. Such an organization is able to work as fluently outside of its boundaries as across its internal departments or divisions. Experience of multi-stakeholder processes has shown that such organizations have successfully learned to work with stakeholders and players outside of its traditional boundaries. These organizations are able to effectively translate its positive impact purpose in practice by co-creating innovative solutions with external stakeholders [20].

Although this research does not allow us to highlight underlying nuances of a leader’s or an organizational mindset shift, Rimanoczy’s work adds insightful value to our discovery [21]. She has grouped the various elements of a sustainability mindset into four categories. Two of which can be attributed to a leader’s mindset shift, and two to the organizational mindset shift. Sustainability minded leaders adopt an ecological worldview, which can be observed through a higher degree of eco-literacy and a clarity of how they see their contribution for this world. They also develop a spiritual intelligence that can be observed in how they see themselves in the context of nature (as one with nature) and in how mindful they are both with themselves and others. Organizational mindsets are more complex phenomenon as they involve a number of individuals. What can be observed in such groups is that they have grasped an understanding of systems thinking, which consists of long-term thinking, a “both/and” approach and a sense of interconnectedness. Organizations that are co-creative also demonstrate a high degree of emotional intelligence across their members. They are fluent in creative innovation, are able to reflect, possessing a high degree of self-awareness and a clear sense of purpose. Our case study research has highlighted elements of these observations reported in Rimanoczy’s valuable work.

Organizations that were “born 3.0”, so-called true sustainability organizations, all demonstrated the outside–in leadership mindset and the co-creative organizational mindset from the start (Alternative Bank Schweiz and Blue Orchard in Switzerland, Merkur Andelskasse in Denmark, and Meso Impact Finance in Luxembourg). These two predictors of change play a critical role when considering how organizations can overcome the innovation challenges to become a Positive Impact Organization. The case study research demonstrates that an outside–in leadership mindset and a co-creative organization mindset are closely related to achieving the four strategic differentiators of a Positive Impact Organization outlined in Section 2. Achieving these can be framed in four transformation challenges:

- The integration challenge of a governance alignment: organizations that have implemented alignment in governance are able to attract suitable investors and are likely to have a board that is more supportive of a progressive sustainability agenda. This makes it significantly easier to integrate sustainability deeply within the organization.

- The priority challenge observed in the organizational culture: organizations with an advanced sustainability culture are inspired and led by a leader or a leadership team that gets the outside–in perspective of sustainability. Such organizations often attract employees who carry a desire to create positive impact in their hearts. Their compensation system is aligned with broader sustainability goals and the organization measures its ambitious sustainability goals. This priority ensures that in times of a crisis, the sustainability topic does not get put on the back-burner.

- The engagement challenge to achieve a positive external validation: organizations that benefit from a positive external recognition of their sustainability efforts have learned to excel in how to engage with external stakeholders. Although traditional firms often consider external stakeholders are a potential danger and handle them with “silver gloves”, truly sustainable firms have learned their lessons in how to engage authentically with critical civil society players and how to integrate constructive external views in their operational decision-making processes. Such open stakeholder engagement becomes the source of entirely new “outside-in” ideas that the organization can translate into new business opportunities.

- The positioning challenge to accomplish the organization’s higher purpose: such organizations have rewritten their purpose in a way to demonstrate their desire to create a positive impact for society and the planet. What differentiates advanced sustainability organizations from other firms with impact-oriented purpose statement is the fact that they have translated such a purpose into their products and services. They have reconsidered and identified markets which are relevant to them. Other firms have often not been able to make this translation from a lofty purpose to an amended or expanded product or service offering and they not only risk facing credibility issues but also cannot benefit from the opportunities such a new purpose potentially holds for them.

Figure 2 connects the four innovation challenges with the two mindset shifts. The Positive Impact Organization has successfully addressed the challenges in the four strategic areas: (1) a governance alignment that facilitates the integration challenge of sustainability; (2) a sustainability culture that prioritizes the role of a business in society; (3) an external validation that confirms the societal stakeholder stance of the organization, and (4) a higher purpose that results in a revised positioning of products and services.

Figure 2. The mindset shift of leaders and the organization and the innovation challenges associated with the strategic differentiators of Positive Impact Organizations

In summary, the outside–in leadership mindset is required to overcome the challenge to achieve a governance alignment, and to implement a sustainability culture. The co-creative organization mindset is needed to successfully work with other societal stakeholders to create a positive impact for the world, which is reflected in new product and service offerings.

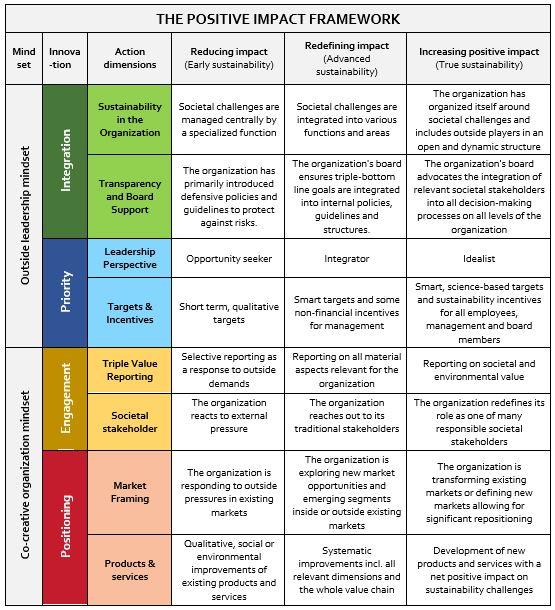

3.2. The Positive Impact Framework (PIF) for Measuring Progress

There are different approaches to address the transformational challenges of an organization set to create a positive impact. Analyzing the case study organizations, it was possible to sharpen the draft framework and to confirm the key innovation strategies which pioneering organizations have applied in their journey. These eight action dimensions are: (1) sustainability in the organization, (2) transparency and board support, (3) leadership perspective, (4) measuring and reporting, (5) societal stakeholder, (6) triple value reporting, (7) market framing, and (8) products and services. The Positive Impact Framework (Table 8) describes these eight action dimensions across the three types of business sustainability. It offers a qualitative assessment for organizations that seek to measure their progress in achieving their positive impact.

The first two innovation challenges are related to the outside–in leadership mindset. The integration challenge depends on a supportive board that understands the importance of integrating sustainability in the organization, so that the transformation towards positive impact creation is not just another change project. The priority challenge is a leadership topic that is unlikely to succeed without a sustainability leader who builds a strong sustainability culture [22]. Although it is not always easy to measure these, the quantitative survey among our case study organizations revealed three relevant indicators of a leadership mindset. Employees and managers of Positive Impact Organizations (PIOs) say four things about their leaders that their peers in early-stage sustainable organizations do not see: PIO leaders (1) integrate sustainability into their decision making, (2) they are willing to take measured risks in pursuit of sustainability, (3) they have a clear vision for sustainability, and (4) they are able to inspire others about sustainability-focused issues and initiatives. Studying the case study organizations revealed further important insights that are outlined below.

Table 1. The Positive Impact Framework.

The integration challenge, which is heavily influenced by investors’ intention, consists of two elements: transparency and board support as one, and the role of the “sustainability function” in the organization as the other. It is highly related to the priority challenge.

Sustainability in the organization addresses how an organization has integrated the topic into its hierarchy and structure. Early sustainability organizations typically create a centrally managed role of a newly appointed sustainability specialist. Often, the role reports to existing functions, such as the corporate secretary, or the communications or marketing head. Advanced sustainability organizations have overcome the limitations of such a centralized role and have integrated sustainability responsibilities into various functions across departments and divisions. True sustainability organizations have reorganized their entire organization around societal challenges they seek to resolve and address, creating multi-functional divisions that are organized to create the products and services that serve its purpose. Such a structure enables the integration of outside actors into an open and dynamic structure.

Transparency and board support are important ways of measuring the degree of sustainability integration. Signs of early sustainability are primarily defensive policies that consist of codes and guidelines to protect against sustainability risks. A sign of advanced sustainability is the degree to which triple-bottom line objectives are integrated into policies and structures. True sustainability organizations are fully transparent and have integrated relevant societal stakeholders into all decision-making processes on all levels of the organization, including the board.

THE INTEGRATION CHALLENGE: A CASE IN POINT:

LANCASTER HOTEL, UK—service industry

The management of the hotel understood the importance of being an exemplary citizen as a business. As a result, sustainability as a topic was anchored in various aspects of the hotel. The head of sustainability was able to launch a number of sustainability initiatives that transformed the hotel step by step. Although initially the products and services were not fundamentally changed, important additions and modifications ensured that everything in the hotel was aligned with its desire to be a positive example. A broader market framing led to a better positioning and changes to how performance was measured. These were important accelerators of change. The organization started to measure value creation more broadly and worked courageously with new stakeholders in their journey to adapt their services offering.

Priority

The priority challenge relates to the organizational culture. Although a sustainability culture consists of many different elements, the research of our 13 sustainability case study organizations has shown that the type of leader on one hand, and targets and incentives on the other side, are the two determining elements to ensure that an organization can act with clarity to generate a positive impact for society.

Leadership perspective is one predictor of success of a Positive Impact Organization. Although early sustainability organizations have leaders that are opportunity seekers, advanced sustainability organizations often have leaders that are integrators. True sustainability organizations are blessed with idealists, leaders that put the societal and planetary well-being at the heart of their vision and put themselves and their organization at the service of improving the state of the world [23].

Targets and incentives including relevant non-financial, sustainability performance indicators is highly relevant in assessing the degree to which an organization has embraced a sustainability culture. Early sustainability organizations tend to create short term, qualitative targets. Advanced sustainability organizations set smart targets and some non-financial incentives for management. True sustainability organizations find answers in how to create value for stakeholders and society and as a result create both moonshot goals as well as smart, science-based targets and sustainability incentives for all employees, management, and board members.

THE PRIORITY CHALLENGE-CASE IN POINT:

RHOMBERG, AUSTRIA—construction industry

The new CEO brought in a new leadership perspective which inspired a higher transparency in the organization, coupled with a deeper engagement of the board. The CEO had a great interest in broadening the range of products and services and openly engaged with new players outside existing business boundaries creating new and stronger bonds with external stakeholders. The outside–in leadership mindset created a strong sustainability culture, which enabled an accelerated transformation. The authentic engagement of CEO Hubert Rhombert was a magnet for new talent and has resulted in remarkable market innovations.

The other two innovation challenges are related to the co-creative organization mindset. The quantitative survey among the case companies provided revealing insights into how employees and managers of true sustainability organizations assess their organization. They see these three things that their peers in early sustainability organizations do not observe: (1) their organization sends a clear and consistent message to external stakeholders about its commitment to sustainability, (2) their organization has mechanisms in place to actively engage with external stakeholders, and (3) their organization encourages sustainability in its supply chain. Further insights derived from the case study organizations are outlined below.

Engagement

The engagement challenge describes the upside potential of an organization’s ability to involve traditional and societal stakeholders in the decision-making processes of the organization. This is — so our research suggests — the second predictor of success to become a Positive Impact Organization. This engagement can be observed by the stakeholder involvement and what type of value creation a company reports on.

The societal stakeholder is a new way for the organization to see itself in society. Traditionally, stakeholders have held an important role in helping the organization to clarify its role along its value chain. Early sustainability organizations tend to be reactive to external pressure and view stakeholders as a potential threat. Advanced sustainability organizations reach out to their traditional stakeholders along the value chain to discover ways to reduce the extended footprint. True sustainability organizations adopt a broader perspective as one of many responsible stakeholders in society. They are changing the playing field from placing themselves at the center (inside–out) to starting by considering how the world is evolving (outside–in).

The triple value reporting of an organization is a good indication of how sustainable an organization is. Early sustainability organizations undertake selective reporting as a response to outside demands. Advanced sustainability organizations report on all material aspects that are relevant for the company. True sustainability organizations engage in the unchartered territory of attempting to report on the societal and environmental value they create, including both negative and positive impacts.

THE ENGAGEMENT CHALLENGE—A CASE IN POINT:

PEBBLES, PAKISTAN—manufacturing industry

Pressing social issues in the neighborhood of the organization were very front of mind of many managers. Ongoing external pressure further increased awareness and triggered a number of consultative meetings with concerned citizens including a number of management and employees participated. Increasingly, the CEO and his leadership team understood that the social crises at their doorsteps may be an opportunity in disguise. They started exploring options for collaboration with local planers and engineers and worked together on a proposal that envisioned a promising future for the concerned neighborhood. Initially, the organization saw this external engagement as a prototype; they deeply cared about the issue but they were not sure how connected it was to the rest of the business. Once a first prototype was implemented, the internal impact was enormous. Employees started to emotionally connect with this new activity of their organizations with many reporting how proud they felt. The growing sustainability culture was palpable and departments started to engage with much less hesitation in new types of collaborations with organizations outside of their market definition. The business boundaries were reconsidered and redefined much more broadly. The initial prototype significantly change the way the organization — its employees and managers — considered themselves. As importantly, external stakeholders validated this new role through their admiration and willingness to work together with the organization that had transformed to be such a good citizen. New opportunities emerged as a result, with the CEO reporting how proud he was of how far they had come and how confident his future outlook had become.

Positioning

The positioning challenge defines the higher purpose dimension of a Positive Impact Organization (PIO). It consists of two key elements: market framing and products and services. Its success is intimately connected to the engagement challenge. Creating relevant products for society requires a trusting and open collaboration with societal stakeholders. It builds on a broader societal perspective.

Market framing is about shifting from reacting to the perspective of the organizational purpose. Early sustainability organizations react to outside pressures in existing markets. Advanced sustainability organizations explore new market opportunities and emerging segments inside or outside existing markets. True sustainability organizations transform existing markets or define entirely new markets as a result of considering new ways of solving existing societal and environmental challenges, resulting, often, in a significant repositioning of future products and services.

Products and services are central to the repositioning of an organization. Early sustainability organizations consider selective improvements of existing products and services. Advanced sustainability organizations undertake systematic improvements across their product and service range, which include all relevant dimensions and the whole life-cycle, resulting in “better product”. True sustainability organizations work on “good products and services that generate a net positive effect” (impact) on sustainability challenges, often along several time horizons [18].

THE POSITIONING CHALLENGE—A CASE IN POINT:

EARLY SUSTAINABLE COMPANY (anonymized)—manufacturing industry

The organization had started to consider sustainability as a result of increasing external pressure. To its management, sustainability issues were risks mapped in the materiality matrix. The CEO defined his role as ensuring the survival of the organization in an increasingly fast-changing world, driven by a competitive mindset of an opportunist. Performance measurements consisted of short-term economic measures to ensure first and foremost shareholder value. The sustainability department reported to the communications department and had a challenging stance in trying to change the organization mindset from inside–out to outside–in. External pressure and eroding markets had forced a rethinking internally and the SDGs provided a welcome new framework to hopefully find new market opportunities, even though the management team was hesitant to what degree to collaborate with external stakeholders it had not previously engaged with. Sustainability had not yet resulted in a broader framing of markets or new service solutions.

3.3. The Strategic Innovation Canvas (SIC) for Getting Started

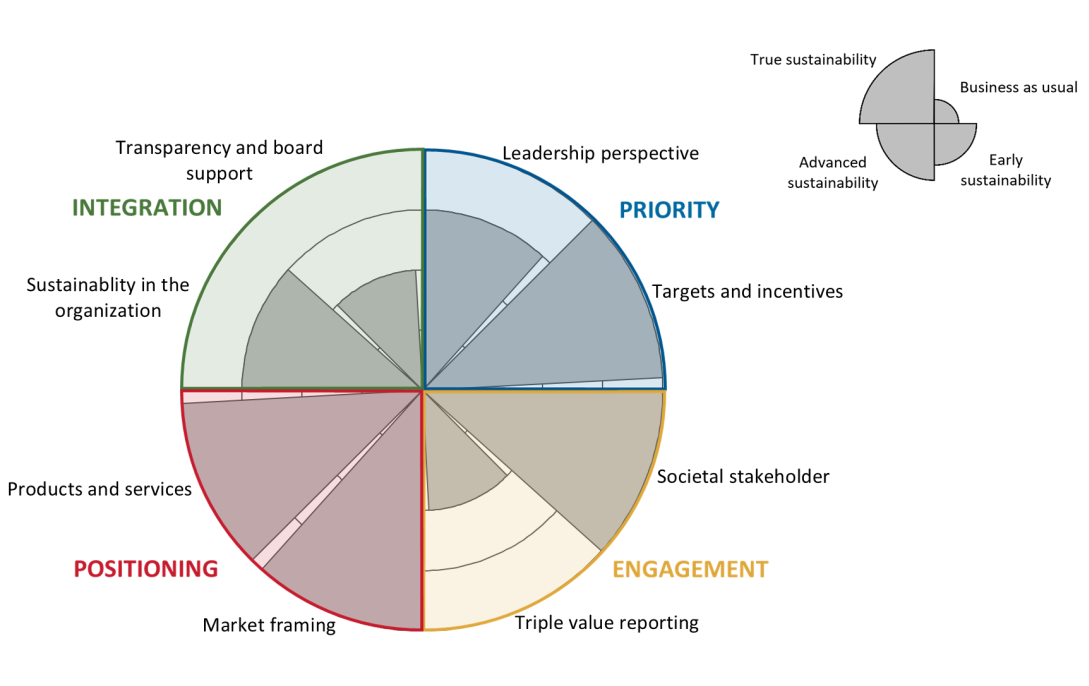

Translating the insights for practitioners ideally results in a tool that provides a meta-level orientation. The SIC (Figure 3) is a concise and visual summary of the Positive Impact Framework, allowing organizations that seek to increase their positive impact to gain a strategic overview to clarify their innovation strategy.

Although each organization needs to determine which of the eight dimensions is the most relevant and appropriate to improve, the case study research suggests that there may be a path of least resistance to become a Positive Impact Organization. Starting with the right kind of a leadership perspective (top right quadrant of Figure 3) to authentically embrace such an endeavor, the organization subsequently embeds such a vision in its targets and incentives. In a second phase, the organization learns to co-create beyond its boundaries as a societal stakeholder (bottom right quadrant) to identify ways to create value for society, the planet, and the economy (triple value reporting). This increased ease of collaboration outside of the organizational boundaries will speed up the implementation of a positive impact purpose. Such a purpose needs to be expressed in a broader market framing and will result in changes in existing and new products and services (bottom left quadrant). Last but not least, the integration of sustainability in the organization and an increased transparency along with a strong support by the board is enabled through the early successes of low-hanging fruits that have been collected in a first circle of the canvas. It closes the loop in a first transformational round (top left quadrant) and may well allow the leadership team to be boosted in its sustainability mindset and the second round of transformation is launched.

Figure 3. The Strategic Innovation Canvas for Positive Impact Organizations.

A further useful application of the SIC lies in its use as an assessment of the current state of an organization during a strategic discussion at the management or board level. Such an assessment can be generated by members of the leadership team or the board completing a straight-forward online assessment: (https://assessment.sdgx.org/index.php?r=survey/index&sid=65264&newtest=Y&lang=en. The online assessment translates the eight action dimensions of the Positive Impact Framework into eight questions and generates a company profile. This profile can be displayed visually (see Figure 4). Such a visual can serve as a starting point of a strategic discussion. Each of the eight dimensions is featured depending on the average assessment of the organization’s leadership team. The higher the score the larger the shaded area. The smallest circle represents business-as-usual, the next larger circle covers early sustainability, thereafter advanced sustainability, and the outer largest circle represents true sustainability, as illustrated with the top right pictogram. For example, the organization featured in Figure 4 has already achieved a level of “true sustainability” in the action dimensions, targets and incentives, societal stakeholder, market framing, and products and services; while it is only at a stage of “early sustainability” in the dimensions triple value reporting and transparency and board support. The visual highlights further opportunities for improvements in the strategic dimension “integration” and to a lesser degree in “engagement” and potentially “priority”.

Figure 4. Example of a current position of an organization when starting its positive impact innovation.

The Strategic Innovation Canvas is a symbol to indicate that organizational transformation is an ongoing creative process and that one dimension often helps the improvement of another and that once a virtual circle is set in motion, the positive energy will help propel the organization forward. The stories of the seven truly sustainable organizations are well documented (https://www.theibs.net/research (accessed on July 27, 2021) and make for inspirational reading for those interested in learning more.

3.4. Relevance to Practice

This entry has contributed to practice in two ways. First, it serves as a hands-on tool to differentiate between green washing and true business sustainability in a Swiss-government-funded sustainability platform. On this platform, organizations can apply for a professionally-produced short documentary featuring their true sustainability. The platform is called Business Sustainability Today (www.Sustainability-Today.com (accessed on July 27, 2021) and organizations complete a self-assessment that reflects the PIF. An expert panel then reviews these self-assessments to confirm the level of sustainability of the organizations.

Second, it was used to co-create a SDG-oriented innovation strategy tool for business. The tool is called SDGXCHANGE (www.SDGX.org (accessed on July 27, 2021) and has been created based on the insights of our case study research and finalized during a stringent prototyping process in collaboration with numerous businesses from different industries [24].

The practice application has helped to validate three of the four strategic differentiators identified in Section 2. The SDGXCHANGE tool enables organizations to revisit their market definition and to create new products and services. As a result, it has proven effective in shaping the “higher purpose” strategic differentiator. In the process of creating new products and services, organizations were incited to involve a broad range of external stakeholders in co-creative workshops. These workshops have helped validate the effectiveness of the strategic differentiator “external validation”. The tool has resulted in discussions about the role of sustainability in the organization, which has in a few cases resulted in an improvement in governance and transparency. An improved “governance alignment”, a strategic differentiator, is best achieved by actively involving the board of directors. The SDGXCHANGE tool is used at the board level to frame a strategic discussion with investors and shareholder representatives and to trigger a strategic process.

It is, however, not just the direct application of this research that demonstrates its usefulness in practice. A parallel effort by CB Bhattacharya and Paul Polman (then CEO of Unilever) highlights near identical action dimensions, or “pain points”, as are highlights in the SIC. Referring explicitly to the mindset shift from inside–out to outside–in, they point to all eight action dimensions. They highlight that (1) “the CEO has to lead this charge”, (2) “it’s important to set clear targets and get all employees to conduct business through the sustainability lens”, (3) “executives are required to engage with multiple external stakeholders”, (4) “incorporating sustainability criteria into financial tools such as integrated reporting”, (5) “understanding what stakeholders within and beyond the value chain are asking of our business”, and “sustainability needs to be put in the precompetitive space”, (6) “top leadership must clarify what is the business’ purpose and where is the growth likely to come from in the future”, (7) “making sustainability part of every employee’s job”, and (8) “making sustainability a priority for the board” [25]. They also confirm that a sustainability initiative is a change process with purpose. This has also become evident in various practice applications of the SDGXCHANGE tool. As a result, the tool includes a change readiness assessment at the start of its process.

References

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218.

- Russell, R. Leadership in the Decade of Action. 2020. Available online: https://www.russellreynolds.com/insights/thought-leadership/Documents/Leadership%20for%20the%20Decade%20of%20Action.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Nagler, J. We Become What We Think—The Key Role of Mindsets in Human Development. International Science Council. Published Online. 2020. Available online: https://council.science/human-development/latest-contributions/we-become-what-we-think-the-key-role-of-mindsets-in-human-development/ (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- PWC/SAM. The Sustainability Yearbook; PWC/SAM: Zurich, Switzerland, 2006.

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the meaning of sustainable business—Introducing a typology from business-as-usual to true business sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 156–174.

- Network for Business Sustainability (NBS). Definition of Business Sustainability. 2012. Available online: http://nbs.net/about/what-we-do/ (accessed on 30 November 2012).

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannoui, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857.

- KPMG. The Road Ahead. The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2017. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2017/10/kpmg-survey-of-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2017.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Bertels, S.; Papania, L.; Papania, D. Embedding Sustainability in Organizational Culture: A Systematic Review of the Body of Knowledge, Network for Business Sustainability. 2010. Available online: https://www.nbs.net/articles/systematic-review-organizational-culture (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Miller Perkins, K. Leadership and Purpose: How to Create a Sustainable Culture; Routledge: Sheffield, UK, 2019.

- Miller Perkins, K. Sustainability: Culture and Leadership Assessment; Miller Consultants Inc.: Louisville, KY, USA, 2011; Available online: www.millerconsultants.com/sustainability.php (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Grayson, D.; Coulter, C.; Lee, M. The Future of Business Leadership; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Pless, N.; Maak, T.; Waldman, D. Different Approaches toward Doing the Right Thing: Mapping the Responsibility Orientations of Leaders. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4–12.

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Transitioning: What does sustainability for business really mean? And when is a business truly sustainable? In Sustainable Business: A One Planet. Approach; Jeanrenaud, S., Jeanrenaud, J.P., Gosling, J., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 381–407.

- Dyllick, T.; Rost, Z. Towards True Product Sustainability. J. Clean. Production 2017, 162, 346–360.

- Business and Sustainable Development Commission. Better Business Better World. Presented at the World Economic Forum in January 2017. Available online: http://report.businesscommission.org/uploads/Executive-Summary.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- March, R.; The Positive Impact Scorecard. Standard & Poor’s. Published 15 April 2020. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/blog/the-positive-impact-scorecard (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Malnight, T.W.; Buche, I.; Dhanaraj, C. Put Purpose at the Core of Your Strategy—It’s How Successful Companies Redefine Their Businesses; Harvard Business Review; Joshua Macht: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019; pp. 2–11.

- WBCSD. World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Vision 2050—Time to Transform; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://timetotransform.biz/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Muff, K. Five Superpowers for Co-Creators—How Change Makers and Business Can. Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals; Routledge: Sheffield, UK, 2018.

- Rimanoczy, I. The Sustainability Mindset Principles—A Guide to Developing a Mindset for a Better World; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Flammer, C.; Bansal, P. Does a long-term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1827–1847.

- Bukhari, N. Pebbles (PVT) Ltd sustainable real estate develops: Building hope. In Award-Winning Case Studies 2015; A Special Issue of Building Sustainable Legacies; Muff, K., Ed.; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2015.

- Von Arx, U. Rhomberg Bau: Sustainability makes sense. In Award-Winning Case Studies 2015; A Special Issue of Building Sustainable Legacies; Ionescu-Somers, A., Ed.; Taylor Francis: Sheffield, UK, 2019.

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Polman, P. Sustainability lessons from the front lines. MIT Sloan Management Review. Winter 2017, 58, 71–78.