| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haruki Koike | + 1370 word(s) | 1370 | 2021-08-25 03:23:41 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 1370 | 2021-08-30 02:33:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

Amyloidosis is a term referring to a group of various protein-misfolding diseases wherein normally soluble proteins form aggregates as insoluble amyloid fibrils. How, or whether, amyloid fibrils contribute to tissue damage in amyloidosis has been the topic of debate. In vitro studies have demonstrated the appearance of small globular oligomeric species during the incubation of amyloid beta peptide (Aβ).

1. Introduction

Amyloidosis is a term referring to a group of toxic gain-of-function protein-misfolding diseases wherein normally soluble proteins aggregate in extracellular spaces as insoluble amyloid fibrils with a beta (β)-sheet structure [1][2]. More than 30 causative amyloidogenic proteins have been reported, and some of them, such as the amyloid β precursor protein (APP) in Alzheimer’s disease, prion protein in prion diseases, immunoglobulin light chain in AL amyloidosis, transthyretin (TTR) in ATTR amyloidosis, and serum amyloid A in AA amyloidosis, cause fatal outcomes [1][3][4][5][6][7][8]. The deposition of amyloid is localized to the central nervous system in Alzheimer’s disease and most prion diseases [1][3][4], whereas systemic deposition occurs in AL, ATTR, and AA amyloidoses [5][7][8][9][10]. How, or whether, amyloid fibrils contribute to these diseases is a topic of debate. The extracellular deposits, composed of amyloid fibrils (i.e., amyloid deposits), were initially regarded as the cause of organ dysfunction resulting from amyloidosis [11][12]. For example, the restriction of ventricular wall mobility due to massive amyloid deposition in the spaces between cardiomyocytes results in heart failure [9][13]. The direct damage of neighboring tissues by amyloid fibrils has also been suggested [11][12][14][15][16][17][18]. In contrast, more recent studies have focused on non-fibrillar precursors of amyloidogenic proteins as the cause of tissue degeneration [19][20][21]. In particular, protein oligomers generated during the process of amyloid fibril formation or released from amyloid fibril aggregates are now considered as causes of cellular dysfunction and degeneration [22][23][24][25]. In support of this view, the severity of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease does not correlate with amyloid plaque formation, suggesting that pre-amyloid aggregates are the cause of disease [26][27]. From this standpoint, clarifying the significance of amyloidogenic protein oligomers is important to understanding the pathophysiology and establishing therapeutic strategies for amyloidosis.

2. Initiation of Protein Aggregation

The misfolding of proteins is an important step in the process of amyloid fibril formation [28]. In ATTR amyloidosis, TTR, which is mainly synthesized in the liver, forms amyloid fibrils due to the dissociation of natively folded tetramers into misfolded monomers [29][30]. In addition, proteolytic cleavage also promotes the misfolding and aggregation of TTR [31][32]. In Alzheimer’s disease, the proteolytic cleavage of APP by secretases results in the production of toxic amyloid β peptide (Aβ), which is prone to aggregation [33]. Furthermore, increased production, decreased clearance, oxidative modification, and phosphorylation of causative proteins are factors that may trigger the process of aggregation [2]. These factors are considered to play an important role in the initiation of protein aggregation in most acquired amyloidoses.

The formation of amyloid fibrils is a dynamic process, with monomers and oligomers being rapidly exchanged for each other depending on various factors that include pH, temperature, and co-solvents [34]. According to studies of serial biopsy specimens obtained from AL, ATTR, and AA amyloidosis patients, even mature amyloid fibril masses disappear when successful disease-modifying therapies are provided [35][36][37]. Electron microscope studies have demonstrated the appearance of dotty or globular structures 4 to 5 nm in diameter and the subsequent formation of short protofibrils 30 to 100 nm in length during an incubation of Aβ in vitro [38].

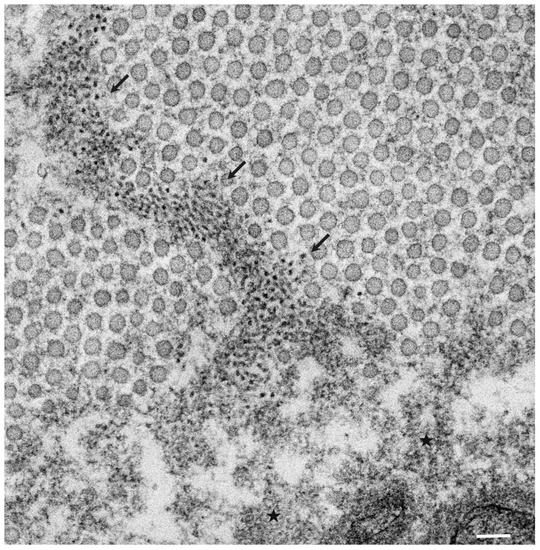

The pathological studies of ATTR amyloidosis have also suggested a similar process of amyloid fibril formation via intermediates [7][17]. Observations of nerve biopsy specimens obtained from patients with hereditary ATTR (ATTRv; v for variant) amyloidosis using electron microscopy suggest that globular structures of similar diameter to Aβ intermediates were generated from amorphous electron-dense materials [7][17]. According to these studies, the deposition of amorphous electron-dense materials was observed in extracellular spaces of the endoneurium, particularly around the microvessels and subperineurial space [17]. These amorphous materials contain non-fibrillar TTR intermediates because they are stained with anti-TTR antibodies but not with Congo red [9]. Clusters of globular structures were also often observed among these extracellular amorphous materials ( Figure 1 ) [17]. The deposition of TTR-positive but Congo red-negative non-fibrillar deposits was observed even in asymptomatic carriers with no amyloid deposits [39]. Similar non-fibrillar TTR deposits have also been reported in transgenic mouse and rat models of ATTRv amyloidosis [40][41]. As the disruption of the blood–nerve barrier of endoneurial microvessels was reported, the TTR in the endoneurium was believed to be derived from the bloodstream [16]. In vitro studies of TTR aggregation suggested that such globular structures are oligomeric intermediates that have cytotoxic effects [42].

3. Formation of Amyloid Fibrils from Intermediates

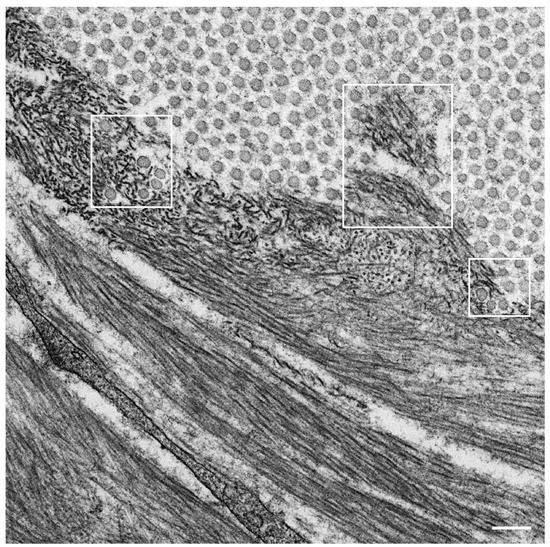

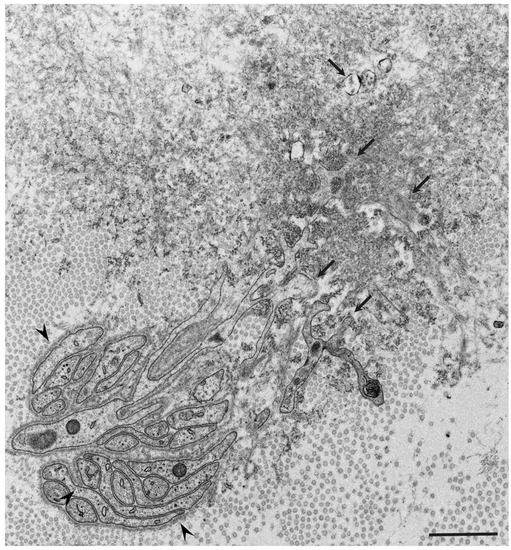

Observations of nerve biopsy specimens from patients with ATTRv amyloidosis using electron microscopy demonstrated a putative chronological sequence of the process of amyloid fibril formation and tissue damage [16][17]. The globular structures found in the extracellular electron-dense materials, which were described earlier, seemed to develop into mature amyloid fibrils because elongated fibrillar structures were frequently found in the vicinity of these globular structures ( Figure 2 ) [17]. During the process of amyloid fibril maturation, amyloid fibrils affect the surrounding structures. For example, collagen fibers seem to get involved in the aggregates of amyloid fibrils, and the basement and cytoplasmic membranes of cells in the endoneurium, including Schwann cells, vascular endothelial cells, and pericytes, apposed by amyloid fibrils also become obscure and appear as if they fuse with amyloid fibrils ( Figure 3 ) [21][43]. Additionally, Schwann cells, particularly small ones associated with small-diameter nerve fibers, become atrophic when they are adjacent to amyloid fibril masses [16][17]. Finally, the contours of these cells sometimes completely disappear, and only the cytoplasmic organelles of these cells remain among the aggregates of amyloid fibrils [17].

Similar atrophy of Schwann cells apposed by amyloid fibrils has also been reported in nerve biopsy specimens from patients with AL amyloidosis, which is another major type of systemic amyloidosis [10][14][15][18][44]. The atrophy and degeneration of vascular endothelial cells, pericytes, and neurites have also been found in brain biopsy specimens from patients with Alzheimer’s disease [45]. These findings support the concept that direct tissue damage induced by amyloid fibrils plays an important role in amyloidosis. In fact, the amount of amyloid deposits seems to be correlated with the extent of neurodegeneration in certain types of ATTRv amyloidosis, particularly the early-onset form of ATTRv amyloidosis [9][46]. However, severe nerve fiber loss was observed in the late-onset form of ATTRv amyloidosis despite a small amount of amyloid deposits, suggesting the presence of other factors for tissue damage [9]. From this standpoint, researchers are now paying attention to the toxicity of non-fibrillar oligomers in tissue damage associated with amyloidosis.

References

- Benson, M.D.; Buxbaum, J.N.; Eisenberg, D.S.; Merlini, G.; Saraiva, M.J.M.; Sekijima, Y.; Sipe, J.D.; Westermark, P. Amyloid nomenclature 2020: Update and recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) nomenclature committee. Amyloid 2020, 27, 217–222.

- Ross, C.A.; Poirier, M.A. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S10–S17.

- Scheltens, P.; Blennow, K.; Breteler, M.M.; de Strooper, B.; Frisoni, G.B.; Salloway, S.; Van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2016, 388, 505–517.

- Sigurdson, C.J.; Bartz, J.C.; Glatzel, M. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Prion Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2019, 14, 497–516.

- Perfetto, F.; Moggi-Pignone, A.; Livi, R.; Tempestini, A.; Bergesio, F.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Systemic amyloidosis: A challenge for the rheumatologist. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 417–429.

- Koike, H.; Tanaka, F.; Hashimoto, R.; Tomita, M.; Kawagashira, Y.; Iijima, M.; Fujitake, J.; Kawanami, T.; Kato, T.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. Natural history of transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: Analysis of late-onset cases from non-endemic areas. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 83, 152–158.

- Koike, H.; Katsuno, M. Transthyretin Amyloidosis: Update on the Clinical Spectrum, Pathogenesis, and Disease-Modifying Therapies. Neurol. Ther. 2020, 9, 317–333.

- Obici, L.; Adams, D. Acquired and inherited amyloidosis: Knowledge driving patients’ care. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2020, 25, 85–101.

- Koike, H.; Misu, K.; Sugiura, M.; Iijima, M.; Mori, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Hattori, N.; Mukai, E.; Ando, Y.; Ikeda, S.; et al. Pathology of early- vs late-onset TTR Met30 familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Neurology 2004, 63, 129–138.

- Koike, H.; Katsuno, M. The Ultrastructure of Tissue Damage by Amyloid Fibrils. Molecules 2021, 26, 4611.

- Coimbra, A.; Andrade, C. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy: An electron microscope study of the peripheral nerve in five cases. I. Interstitial changes. Brain 1971, 94, 199–206.

- Thomas, P.K.; King, R.H. Peripheral nerve changes in amyloid neuropathy. Brain 1974, 97, 395–406.

- Koike, H.; Okumura, T.; Murohara, T.; Katsuno, M. Multidisciplinary Approaches for Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Cardiol. Ther. 2021, 1–23.

- Vital, C.; Vallat, J.M.; Deminiere, C.; Loubet, A.; Leboutet, M.J. Peripheral nerve damage during multiple myeloma and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: An ultrastructural and immunopathologic study. Cancer 1982, 50, 1491–1497.

- Sommer, C.; Schröder, J.M. Amyloid neuropathy: Immunocytochemical localization of intra- and extracellular immunoglobulin light chains. Acta Neuropathol. 1989, 79, 190–199.

- Koike, H.; Ikeda, S.; Takahashi, M.; Kawagashira, Y.; Iijima, M.; Misumi, Y.; Ando, Y.; Ikeda, S.-I.; Katsuno, M.; Sobue, G. Schwann cell and endothelial cell damage in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Neurology 2016, 87, 2220–2229.

- Koike, H.; Nishi, R.; Ikeda, S.; Kawagashira, Y.; Iijima, M.; Sakurai, T.; Shimohata, T.; Katsuno, M.; Sobue, G. The morphology of amyloid fibrils and their impact on tissue damage in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: An ultrastructural study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 394, 99–106.

- Koike, H.; Mouri, N.; Fukami, Y.; Iijima, M.; Matsuo, K.; Yagi, N.; Saito, A.; Nakamura, H.; Takahashi, K.; Nakae, Y.; et al. Two distinct mechanisms of neuropathy in immunoglobulin light chain (AL) amyloidosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 421, 117305.

- Walsh, D.M.; Klyubin, I.; Fadeeva, J.V.; Cullen, W.K.; Anwyl, R.; Wolfe, M.S.; Rowan, M.J.; Selkoe, D.J. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 2002, 416, 535–539.

- Caughey, B.; Lansbury, P.T. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: Separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 26, 267–298.

- Koike, H.; Katsuno, M. Ultrastructure in Transthyretin Amyloidosis: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Insights. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 11.

- Kayed, R.; Sokolov, Y.; Edmonds, B.; McIntire, T.M.; Milton, S.C.; Hall, J.E.; Glabe, C.G. Permeabilization of lipid bilayers is a common conformation-dependent activity of soluble amyloid oligomers in protein misfolding diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 46363–46366.

- Benilova, I.; Karran, E.; De Strooper, B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: An emperor in need of clothes. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 349–357.

- Evangelisti, E.; Cascella, R.; Becatti, M.; Marrazza, G.; Dobson, C.M.; Chiti, F.; Stefani, M.; Cecchi, C. Binding affinity of amyloid oligomers to cellular membranes is a generic indicator of cellular dysfunction in protein misfolding diseases. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32721.

- Jayaraman, S.; Gantz, D.L.; Haupt, C.; Gursky, O. Serum amyloid A forms stable oligomers that disrupt vesicles at lysosomal pH and contribute to the pathogenesis of reactive amyloidosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6507–E6515.

- Tomiyama, T.; Nagata, T.; Shimada, H.; Teraoka, R.; Fukushima, A.; Kanemitsu, H.; Takuma, H.; Kuwano, R.; Imagawa, M.; Ataka, S.; et al. A new amyloid beta variant favoring oligomerization in Alzheimer’s-type dementia. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 377–387.

- Tomiyama, T.; Matsuyama, S.; Iso, H.; Umeda, T.; Takuma, H.; Ohnishi, K.; Ishibashi, K.; Teraoka, R.; Sakama, N.; Yamashita, T.; et al. A mouse model of amyloid beta oligomers: Their contribution to synaptic alteration, abnormal tau phosphorylation, glial activation, and neuronal loss in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 4845–4856.

- Eisele, Y.S.; Monteiro, C.; Fearns, C.; Encalada, S.E.; Wiseman, R.L.; Powers, E.T.; Kelly, J.W. Targeting protein aggregation for the treatment of degenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 759–780.

- Blake, C.C.; Geisow, M.J.; Swan, I.D.; Rerat, C.; Rerat, B. Strjcture of human plasma prealbumin at 2-5 A resolution. A preliminary report on the polypeptide chain conformation, quaternary structure and thyroxine binding. J. Mol. Biol. 1974, 88, 1–12.

- Kelly, J.W. Amyloid fibril formation and protein misassembly: A structural quest for insights into amyloid and prion diseases. Structure 1997, 5, 595–600.

- Mangione, P.P.; Verona, G.; Corazza, A.; Marcoux, J.; Canetti, D.; Giorgetti, S.; Raimondi, S.; Stoppini, M.; Esposito, M.; Relini, A.; et al. Plasminogen activation triggers transthyretin amyloidogenesis in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 14192–14199.

- Dasari, A.K.R.; Arreola, J.; Michael, B.; Griffin, R.; Kelly, J.W.; Lim, K.H. Disruption of the CD Loop by Enzymatic Cleavage Promotes the Formation of Toxic Transthyretin Oligomers through a Common Transthyretin Misfolding Pathway. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 2319–2327.

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608.

- Buell, A.K.; Dobson, C.M.; Knowles, T.P. The physical chemistry of the amyloid phenomenon: Thermodynamics and kinetics of filamentous protein aggregation. Essays Biochem. 2014, 56, 11–39.

- Okuda, Y.; Takasugi, K. Successful use of a humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, to treat amyloid A amyloidosis complicating juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 2997–3000.

- Tsuchiya-Suzuki, A.; Yazaki, M.; Sekijima, Y.; Kametani, F.; Ikeda, S.-I. Steady turnover of amyloid fibril proteins in gastric mucosa after liver transplantation in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Amyloid 2013, 20, 156–163.

- Katoh, N.; Matsushima, A.; Kurozumi, M.; Matsuda, M.; Ikeda, S.-I. Marked and Rapid Regression of Hepatic Amyloid Deposition in a Patient with Systemic Light Chain (AL) Amyloidosis after High-dose Melphalan Therapy with Stem Cell Transplantation. Intern. Med. 2014, 53, 1991–1995.

- Nybo, M.; Svehag, S.E.; Nielsen, E.H. An ultrastructural study of amyloid intermediates in A beta1-42 fibrillogenesis. Scand. J. Immunol. 1999, 49, 219–223.

- Sousa, M.M.; Cardoso, I.; Fernandes, R.; Guimarães, A.; Saraiva, M.J. Deposition of transthyretin in early stages of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy: Evidence for toxicity of nonfibrillar aggregates. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 159, 1993–2000.

- Sousa, M.M.; Fernandes, R.; Palha, J.A.; Taboada, A.; Vieira, P.; Saraiva, M.J. Evidence for early cytotoxic aggregates in transgenic mice for human transthyretin Leu55Pro. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 161, 1935–1948.

- Ueda, M.; Ando, Y.; Hakamata, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Yamashita, T.; Obayashi, K.; Himeno, S.; Inoue, S.; Sato, Y.; Kaneko, T.; et al. A transgenic rat with the human ATTR V30M: A novel tool for analyses of ATTR metabolisms. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 352, 299–304.

- Dasari, A.K.R.; Hughes, R.M.; Wi, S.; Hung, I.; Gan, Z.; Kelly, J.W.; Lim, K.H. Transthyretin Aggregation Pathway toward the Formation of Distinct Cytotoxic Oligomers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 33.

- Koike, H.; Fukami, Y.; Nishi, R.; Kawagashira, Y.; Iijima, M.; Sobue, G.; Katsuno, M. Clinicopathological spectrum and recent advances in the treatment of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Neurol. Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 7, 166–173.

- Vallat, J.-M.; Vital, A.; Magy, L.; Martin-Négrier, M.-L.; Vital, C. An Update on Nerve Biopsy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 68, 833–844.

- Wisniewski, H.M.; Wegiel, J.; Wang, K.C.; Lach, B. Ultrastructural studies of the cells forming amyloid in the cortical vessel wall in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1992, 84, 117–127.

- Sobue, G.; Nakao, N.; Murakami, K.; Yasuda, T.; Sahashi, K.; Mitsuma, T.; Sasaki, H.; Sakaki, Y.; Takahashi, A. Type I familial amyloid polyneuropathy. A pathological study of the peripheral nervous system. Brain 1990, 113, 903–919.