2. Analysis on Results

2.1. Characteristics of Sample

The final dataset contained 664 women with a mean age of 33.3 years (SD = 4.8), of whom 172 (25.9%) were Toxoplasma-positive. The mean age of infected women was higher than the mean age of uninfected women (p = 0.027; Table 1). We found no differences in the size of place of residence, level of education, smoking, or prevalence of fertility disorders between Toxoplasma-positive and Toxoplasma-negative women (see Table 1 for more details on sample characteristics).

Table 1. Characteristics of women and men samples depending on toxoplasmosis.

| |

Women |

Men |

| |

toxo-neg. |

toxo-pos. |

toxo-neg. |

toxo-pos. |

| N = 492 |

N = 172 |

N = 513 |

N = 164 |

| Mean age (SD) |

33.0 (4.9) |

34.0 (4.3) |

35.5 (5.4) |

36.1 (5.4) |

| Size of place of residence (no. of inhabitants) |

|

|

|

|

| Up to 1000; N (%) |

64 (13.3) |

27 (16.1) |

79 (15.6) |

35 (21.6) |

| 1000–5000; N (%) |

69 (14.3) |

22 (13.1) |

59 (11.7) |

19 (11.7) |

| 5000–50,000; N (%) |

104 (21.6) |

36 (21.4) |

107 (21.2) |

31 (19.1) |

| 50,000–100,000; N (%) |

24 (5.0) |

7 (4.2) |

19 (3.8) |

10 (6.2) |

| 100,000–500,000; N (%) |

13 (2.7) |

1 (0.6) |

7 (1.4) |

8 (4.9) |

| Over 500,000; N (%) |

208 (43.2) |

75 (44.6) |

234 (46.3) |

59 (36.4) |

| Missing data |

10 |

4 |

8 |

2 |

| Level of education |

|

|

|

|

| Highschool without graduation or lower; N (%) |

63 (13.0) |

26 (15.2) |

111 (21.8) |

43 (26.9) |

| Highschool with graduation; N (%) |

187 (38.7) |

65 (38.0) |

196 (38.4) |

67 (41.9) |

| University; N (%) |

233 (48.2) |

80 (46.8) |

203 (39.8) |

50 (31.3) |

| Missing data |

9 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

| Smoking |

|

|

|

|

| No; N (%) |

324 (76.8) |

121 (77.6) |

301 (70.5) |

94 (69.1) |

| Yes; N (%) |

98 (23.2) |

35 (22.4) |

126 (29.5) |

42 (30.9) |

| Missing data |

70 |

16 |

86 |

28 |

| Fertility disorder |

|

|

|

|

| No; N (%) |

108 (32.0) |

38 (31.7) |

276 (58.1) |

80 (51.3) |

| Yes; N (%) |

229 (68.0) |

82 (68.3) |

199 (41.9) |

76 (48.7) |

| Missing data |

155 |

52 |

38 |

8 |

The dataset also contained 677 men with mean age of 35.6 years (SD = 5.4), of whom 164 (24.2%) were Toxoplasma-positive. The mean age of infected men did not differ from the mean age of uninfected men (p = 0.116; Table 1). We found that Toxoplasma-positive men were significantly more likely to reside in a place with fewer inhabitants than Toxoplasma-negative men were (χ2 = 14.1, p = 0.015). We found no differences in level of education, smoking, or prevalence of fertility disorders between Toxoplasma-positive and Toxoplasma-negative men. (For further details of sample characteristics, see Table 1).

The prevalence of toxoplasmosis in women (25.9%) did not significantly differ from the prevalence of toxoplasmosis in men (24.2%, χ2 = 0.503, p = 0.478). The BDI-II score was significantly higher in women than in men (Tau = −0.081, p ≤ 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.25), in fertile women than fertile men (Tau = −0.072, p = 0.016, Cohen’s d = 0.22), and in infertile women than in infertile men (Tau = −0.099, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.32).

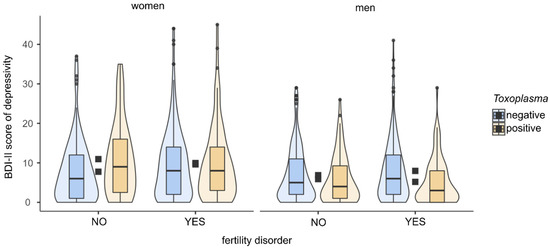

2.2. A Study of Depression in Women

Partial Kendall correlation controlled for age showed no significant differences in BDI-II score between infected and uninfected women (p = 0.494) or between women with and without a diagnosed fertility disorder (p = 0.089). In follow-up analyses, we assessed the influence of toxoplasmosis on depression separately for fertile and infertile women. In fertile women, we found a higher BDI-II score in Toxoplasma-positive than in Toxoplasma-negative women (Tau = 0.145, p = 0.010, Cohen’s d = 0.48). In infertile women, we found no significant difference in BDI-II score between Toxoplasma-positive and Toxoplasma-negative women (p = 0.717). For more details of analyses, see Table 2 and Figure 1.

Figure 1. BDI-II scores in women and men according to toxoplasmosis status and fertility problems. The figure shows boxplots with medians, interquartile ranges in violin plots. Black squares show mean depression scores.

Table 2. BDI-II scores in women and men according to toxoplasmosis and fertility problems.

| |

Women |

Men |

| |

N |

Mean |

SD |

Tau |

Cohen’s d |

p |

N |

Mean |

SD |

Tau |

Cohen’s d |

p |

| Toxo-pos. |

172 |

9.4 |

9.2 |

0.018 |

0.06 |

0.494 |

164 |

5.9 |

6.4 |

−0.075 |

0.25 |

0.003 |

| Toxo-neg. |

492 |

8.8 |

8.3 |

513 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

| Fertile |

146 |

8.6 |

8.5 |

0.053 |

0.16 |

0.089 |

356 |

6.7 |

6.7 |

0.028 |

0.09 |

0.295 |

| Infertile |

311 |

9.7 |

9.1 |

275 |

7.2 |

7.3 |

| Fertile, toxo-pos. |

38 |

10.9 |

9.4 |

0.145 |

0.48 |

0.010 |

80 |

5.9 |

6.1 |

−0.48 |

0.16 |

0.173 |

| Fertile, toxo-neg. |

108 |

7.8 |

8.1 |

276 |

6.9 |

6.8 |

| Infertile, toxo-pos. |

82 |

10.0 |

9.5 |

0.014 |

0.03 |

0.717 |

76 |

5.2 |

5.9 |

−0.152 |

0.48 |

<0.001 |

| Infertile, toxo-neg. |

229 |

9.6 |

9.0 |

199 |

8.0 |

7.7 |

This table shows the results of partial Kendall correlation controlled for age in women and men according to toxoplasmosis status and fertility problems.

2.3. A Study of Depression in Men

Partial Kendall correlation controlled for age showed a higher BDI-II score in Toxoplasma-negative than in Toxoplasma-positive men (Tau = −0.075, p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = 0.25). The relationship remained significant even after filtering out the influence of size of residence (Tau = −0.066, p = 0.011, Cohen’s d = 0.22). The results showed no difference in BDI-II score between men with and without a diagnosed fertility disorder (p = 0.295). In fertile men, we found no significant difference in the BDI-II score between Toxoplasma-positive and Toxoplasma-negative men (p = 0.173). In the group of infertile men, on the other hand, we found a higher BDI-II score in Toxoplasma-negative than in Toxoplasma-positive men (Tau = −0.152, p ≤ 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.48). See Table 2 and Figure 1 for more details of the analyses.

3. Current Insights

We studied the effect of latent toxoplasmosis on depression in a specific group of men and women, namely the clients of a fertility clinic. Similarly to Faramarzi et al.

[1], who studied the differences in BDI scores in women and men undergoing artificial insemination, we found higher depression levels in women than in men. On the other hand, although a higher prevalence of toxoplasmosis has been repeatedly demonstrated in women than in men in the Czech Republic

[2][3], we did not find this difference in our study. This may be due to our atypical sample of participants (clients of the Center for Assisted Reproduction) because a higher prevalence of toxoplasmosis has been observed in infertile men

[4][5] and infertile women

[6].

We found no significant difference in depression levels between

Toxoplasma-positive and

Toxoplasma-negative women in the dataset as a whole; however, in women without fertility disorders we found that

Toxoplasma-positive women are significantly more depressed than those who are

Toxoplasma-negative. These results are consistent with studies that have shown higher depression levels in

Toxoplasma-positive veteran women

[7] and in pregnant women

[8]. We found no significant difference in depression levels between

Toxoplasma-positive and

Toxoplasma-negative women who had been diagnosed with fertility problems. Depression scores in these two groups were similar to those found in

Toxoplasma-positive women without fertility problems. Infertility in women is associated with increased depression

[9] and, indeed, in our sample the negative impact of infertility on depression in women was close to statistical significance (

p = 0.089). The impact of toxoplasmosis on depression may thus be masked by the stronger effect of infertility. Our sample contained more women with diagnosed fertility issues (68%) than those without and it also contained less

Toxoplasma-positive (26%) than

Toxoplasma-negative women, which could explain why we found no significant effect of toxoplasmosis in the sample of women as a whole.

We found a significant difference in depression levels between

Toxoplasma-positive and

Toxoplasma-negative men in the whole dataset and in the subset of men with a pathological spermiogram. Consistent with a previously published study

[10], our results also indicate that

Toxoplasma-positive men could be protected from depression. A host’s infection is characterized by elevated levels of IL-10

[11][12][13], which can reduce depression via its immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory activities

[14][15]. Flegr et al.

[16] suggest that this could reduce BDI-II depression scores in nonclinical populations of

Toxoplasma-positive men. This mechanism alone, however, cannot explain why the depression-protective effect of toxoplasmosis was not observed in women and why

Toxoplasma-positive women without fertility problems had significantly higher depression scores than

Toxoplasma-negative women.

Interestingly, our results show that latent toxoplasmosis affects depression levels in the opposite direction in men and women: they increase in women and decrease in men. Significant differences between men and women in the effect of latent toxoplasmosis on personality changes are known to exist.

Toxoplasma-positive men seem to be less observant of rules and be more suspicious, jealous, and dogmatic than

Toxoplasma-negative men, while

Toxoplasma-positive women are more warm-hearted, easygoing, conscientious, persistent, and moralistic than

Toxoplasma-negative women

[17][18][19][20]. These opposite behavioral responses to

T. gondii infection have been explained by the contrasting reactions of men and women to the chronic stress associated with lifelong infection

[21][22]. To cope with stress, women usually seek and provide social support

[23][24][25], while men use more individualistic and antisocial strategies

[25][26]. Similarly, an evolutionary explanation suggests that the difference between men’s “fight or flight” and women’s “tend and befriend” response to stress stems from women’s need to protect children and maintain social relationships

[27]. From a physiological point of view, Kudielka and Kirschbaum observed sex differences in the HPA axis stress responses

[28]. It is indeed possible that stress-related mechanisms could play a role in the observed differences in the effect of toxoplasmosis on depression scores in men and women detected in our study.

Recent meta-analyses which portrayed no relationship between toxoplasmosis and major depression

[29][30] were based on samples of psychiatric patients. In the present study, on the other hand, we excluded subjects who were taking antidepressants from our analyses. Moreover, some the studies referenced above examined the relationship between toxoplasmosis and depression based on pooled data collected from both sexes, which would have obscured the above-mentioned differences between the sexes. In the meta-analysis of Nayeri et al.

[29], it was impossible to separately analyze men and women because the data were not available in all studies covered by the article. The results of Suvisaari et al.

[31], who measured depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (as in our study), support the hypothesis of sex-differential outcomes. They found higher BDI scores in

Toxoplasma-positive individuals in a representative Finnish sample. When, however, they performed analyses separately for men and women, they found a higher BDI score only in

Toxoplasma-infected women than

Toxoplasma-uninfected women. In men, they found no such difference in BDI scores between

Toxoplasma-infected and uninfected individuals.

Differences in the results of various studies may also be attributed to differences in the measurement of depression. Some studies did not measure the severity of depression and only examined the prevalence of toxoplasmosis in psychiatric patients compared to healthy controls; this is summarized in a meta-analysis by Sutterland et al.

[30]. In our study, we measured depression using a standardized Czech version

[32] of the Beck Depression Inventory-II

[33]. Although Kamal et al.

[34] found significantly higher depression scores measured by the Beck Depression Inventory in

Toxoplasma-positive psychiatric patients than in

Toxoplasma-negative patients, unfortunately they did not perform the analysis separately in men and women.

Behavioral changes associated with latent toxoplasmosis have long been studied and interpreted within the theoretical framework of the so-called ‘manipulation hypothesis’, which states that parasites can alter the behavior of their hosts so as to aid their transfer from intermediate hosts to a definitive host by predation

[35]. However, association does not necessarily mean causality. The observed changes in behavior and personality between

Toxoplasma-positive and

Toxoplasma-negative subjects may be either the cause or the effect of toxoplasmosis. Changes caused by toxoplasmosis could be either the product of

Toxoplasma’s above-mentioned manipulative activity

[35], side effects of pathological processes in the infected organism, or adaptive or maladaptive host responses to parasitic infection. However, it is also possible that individuals with different behaviors and personalities may differ in their susceptibility to

Toxoplasma infection or exhibit different levels of risk-taking behaviors that lead to infection. In human studies, it is impossible to directly test the direction of causality between these phenomena. Results of longitudinal studies in humans

[18][19] and experiments in laboratory animals

[36][37][38] do, however, provide support for the hypothesis of infection-induced behavioral changes.

The likelihood of

T. gondii infection is known to increase with age. In our dataset, the mean age was higher in

Toxoplasma-positive women than in

Toxoplasma-negative ones. In men, we found no association between age and

Toxoplasma status. A recent epidemiological study

[2] conducted in the Czech Republic had shown that the prevalence of toxoplasmosis in boys and girls is similar until the age of 19. At about 30 years of age, the prevalence is significantly higher in women than in men. After this age, the prevalence in men stagnates or decreases, while in women it increases until the age of 50. The traditional explanation for this increasing prevalence of toxoplasmosis in women of childbearing age is their involvement in cooking and tasting raw meat

[3]. The possible transmission of

T. gondii from men to women by sexual intercourse

[39][40] and oral sex

[41] is also discussed in the literature. It is thus possible that in women, infection rates increase more markedly with age than in men. Women seem to have a greater chance of encountering more sources of

T. gondii infection than men do. One of the main risk factors for

Toxoplasma infection is the size of place of residence

[42]. In our study, we observed an effect of size of place of residence on toxoplasmosis in men only. This study was part of a larger study on the effects of latent toxoplasmosis on human fertility. It included an epidemiological study

[40] which showed that the main risk factors for women were the size of place of residence in childhood and infection of their sexual partner. Other risk factors connected with

T. gondii infection—such as eating poorly washed root vegetables and raw meat, contact with garden soil, and cat keeping—were not significantly associated with toxoplasmosis in women. In men, however, the authors observed more typical sources of

T. gondii infection, namely the size of place of residence in childhood and contact with garden soil.

4. Conclusions

Our results showed that the effect of toxoplasmosis on depression goes in the opposite direction in men and in fertile women. While toxoplasmosis seems to protect men from depression, it appears to increase the likelihood of depression in women. Our results concur with previous anecdotal observations of a lower incidence of major depression in men with toxoplasmosis

[10]. This interaction between toxoplasmosis, sex, and depression could help explain the inconsistent results of previous studies and the large heterogeneity of results reported in meta-analytic studies. The effects of toxoplasmosis on men and women are likely to interfere with each other and the outcome of studies also depends on the male-to-female ratio in the studied sample. Our results suggest that in future studies on the effects of toxoplasmosis on depression in humans, data on men and women should always be analyzed separately.