| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Buket Soyyilmaz | + 1355 word(s) | 1355 | 2021-08-20 14:04:41 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1355 | 2021-08-26 05:44:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are non-digestible and structurally diverse complex carbohydrates that are highly abundant in human milk. To date, more than 200 different HMO structures have been identified. Their concentrations in human milk vary according to various factors such as lactation period, mother’s genetic secretor status, and length of gestation (term or preterm).

1. Introduction

Breastfeeding has been associated with lower rates of infectious diseases and infantile mortality, reduced risk for obesity, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBS), and type II diabetes [1][2][3]. In addition to the milk macronutrients such as lactose, lipids, and proteins, human milk contains complex carbohydrate structures known as human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), which attract significant attention since they constitute the largest remaining compositional difference between breastmilk and infant formula.

HMOs constitute the third most abundant solid component of human milk, exceeding the amount of protein [4]. Compared to the milk oligosaccharide fraction of human milk, some remarkable differences are observed in the milk oligosaccharide fraction of other mammals: (a) the total amount of milk oligosaccharides are typically significantly lower [5][6], particularly for domestic farmed animals [7]; (b) the structural complexity and bias of individual structures is lower and different [8][9][10]; and (c) different carbohydrate epitopes are detected [11][12]. In addition to their unique abundance in human milk, there is evidence that HMOs are present in the maternal serum during early gestation, in the umbilical cord blood, and in amniotic fluid [13][14][15].

HMOs are largely indigestible by the infant, hence do not function as direct energy resources for the infant. The majority reach the colon where they are utilized by specific infant gut bacteria and approximately 1% is absorbed [16][17]. The HMO profile of human milk appears fundamental for shaping the gut microbiota of the infant by selectively stimulating the growth of specific bacteria, especially bifidobacteria [18]. The bifidogenic effects found in breastfed infants include proliferation of specific bifidobacteria such as Bifidobacterium infantis, B. breve, and B. bifidum, whose genomes encode a large proportion of oligosaccharide processing and transporting genes clustered within conserved loci [19][20][21][22]. The ability of these bifidobacterial species to utilize HMOs implies a co-evolution, where the glycans produced by the host have served as a carbon and energy source for these bifidobacterial species [23]. Bifidobacterial abundance have been linked to host protection from pathogenic bacteria by helping prepare the mucosal immune system, consequently decreasing susceptibility to various diseases later in life [24]. In addition to their bifidogenic activity, HMOs have also shown to be able to directly or indirectly affect mucosal and systemic immunity, help reduce the risk of pathogenic infection and may support brain development in infants [25][26][27][28][29].

2. Structures and Abbreviations of HMOs

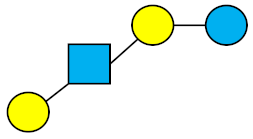

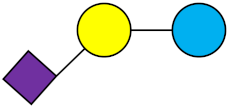

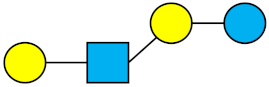

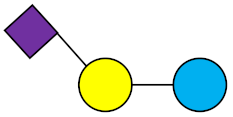

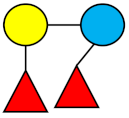

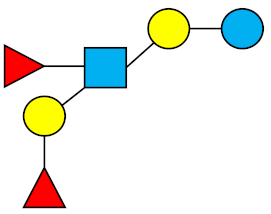

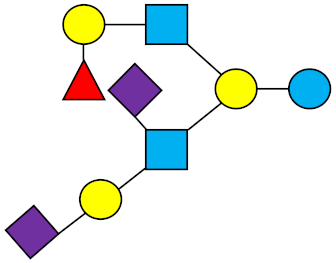

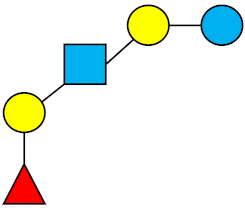

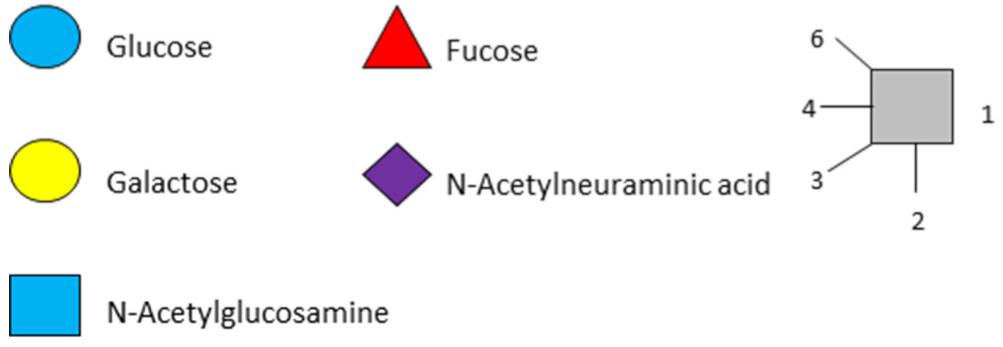

All HMOs derive from lactose (galactosyl-β1-4-glucose) and the HMO fraction of human milk is characterized by extension with four monosaccharides: N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc), D-galactose (Gal), sialic acid (Neu5Ac), and/or L-fucose (Fuc). GlcNAc and galactose are added in specific order and linkages to form the neutral-core structures. While Neu5Ac and Fuc can be present on the terminal positions of either lactose or the core structures, forming sialylated and fucosylated groups. The resulting composition of the HMO fraction is complex and diverse with more than 200 different HMO structures detected by sensitive mass spectrometry [30][31][32]. Names, abbreviations, and structures of the most abundant HMOs reported are listed in Table 1. The collective body of analytical data shows that HMOs can be classified into three fundamental structure classes: (1) neutral-core HMOs (containing GlcNAc); (2) neutral fucosylated HMOs (containing fucose); and (3) acidic HMOs (acidic fucosylated and acidic nonfucosylated) (containing sialic acid). Table 2 lists the 15 most abundant structures. For further information on the chemical structures of individual HMOs, it is recommended to refer to Chen et al. (2015), who provide an elaborate resource to discover the structures of HMOs [32].

Table 1. Structures of the 15 most abundant HMOs in mature human milk.

| Abbreviation | Name | Structure | Abbreviation | Name | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral HMOs (neutral core and neutral fucosylated) | Acidic non-fucosylated HMOs | ||||

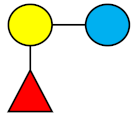

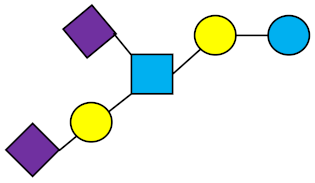

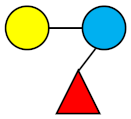

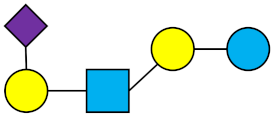

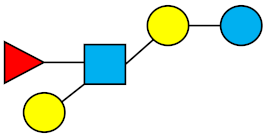

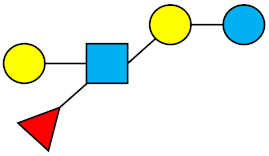

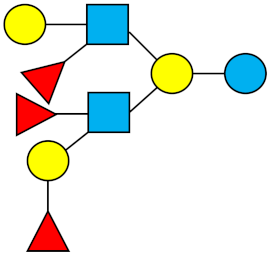

| LNT | Lacto-N-tetraose |  |

3′-SL | 3′-Sialyllactose |  |

| LNnT | Lacto-N-neotetraose |  |

6′-SL | 6′-Sialyllactose |  |

| 2′-FL | 2′-Fucosyllactose |  |

DSLNT | Disialyllacto-N-tetraose |  |

| 3-FL | 3-Fucosyllactose |  |

LST c | Sialyllacto-N-neotetraose c |  |

| DFL (LDFT) | Difucosyllactose |  |

Acidic fucosylated HMOs | ||

| LNDFH-I (DFLNT) | Lacto-N-difucohexaose I |  |

FDS-LNH-I | Fucosyldisialyllacto-N-hexaose I |  |

| LNFP-I | Lacto-N-fucopentaose I |  |

|

||

| LNFP-II | Lacto-N-fucopentaose II |  |

|||

| LNFP-III | Lacto-N-fucopentaose III |  |

|||

| TF-LNH | Trifucosyllacto-N-hexaose |  |

|||

Table 2. Distribution of mothers’ phenotypes and corresponding milk groups.

| Secretor Status | Secretor | Non-Secretor | Secretor | Non-Secretor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Milk Phenotype | Se+/Le(a−b+) | Se−/Le(a+b−) | Se+/Le(a−b−) | Se−/Le(a−b−) |

| α1,2-fucosylated HMOs (FUT2 enzyme 1) |

+ | − | + | − |

| α1,3-fucosylated HMOs (FUT3, FUT5, FUT6 enzymes) | + | + | + | + |

| α1,4-fucosylated HMOs (FUT3 enzyme) | + | + | − | − |

| Typical frequency in global population | 70% | 20% | 9% | 1% |

1 Group 1 (secretor) mothers express both FUT2 and FUT3. Group 2 (non-secretor) mothers express FUT3 but not FUT2. Group 3 (secretor) mothers express FUT2 but not FUT3. Group 4 (non-secretor) mothers express neither FUT2 nor FUT3 [33]. FUT = fucosyltransferase.

3. Factors Influencing HMO Variability

The composition and concentration of individual HMO structures in human milk vary according to genetic and non-genetic factors. Even though neither carbohydrate nor oligosaccharide synthesis is directly genetically encoded (unlike DNA, RNA, and proteins), HMO variability is strongly dependent on the activity of two specific enzymes that are encoded by the Secretor (Se) and Lewis (Le) genes in the mother [27][29]. Se and Le genes encode the enzymes α1-2-fucosyltransferase (FUT2) and α1-3/4-fucosyltransferase (FUT3) respectively, both affecting the biosynthesis of fucosylated HMOs [27]. Milk from women with inactivated FUT2—due to a diversity of different mutations in both alleles of the Se gene—contain zero or only traces of the α1-2-fucosylated HMOs. Similarly, FUT3 activity can be inactivated (or severely reduced) due to a diversity of different mutations in both alleles of the Le gene, thus Lewis-negative women’s milk contain zero or only traces of the α1-4-fucosylated HMOs (α1-3-fucosylation is encoded by several enzymes and is therefore not eliminated by FUT3 deactivation). Therefore, mothers who carry the Se gene express FUT2 enzyme while mothers who do not carry Se do not express the FUT2 enzyme. The interplay of the FUT2 and FUT3 enzymes leads to two main types of Lewis antigens (Lea and Leb) and four common milk phenotypes are observed: Se+/Le(a−b+), Se-/Le(a+b−), Se+/Le(a−b−), Se−/Le(a−b−). Reflecting these phenotypic differences, HMO profiles in lactating mothers are classified into four milk phenotypes, or four different ‘milk groups’ resulting in distinct structural features in their oligosaccharide fraction (Table 1) [33][34]. There are also different consequences of each milk group for the infant postulated. For instance, moderate-to-severe and calicivirus-associated diarrhea occurred less often in infants whose milk contained high levels of 2-linked fucosylated HMOs, suggesting that HMO profile is clinically relevant for incidence of diarrhea [35].

The highest HMO concentrations are generally found in colostrum (first milk). Other than lactation period, the non-genetic factors contributing to the quantitative and structural variability of HMOs among mothers are still to be unraveled. There is evidence demonstrating HMO variability across different populations [36][37] which is possibly explained in large part by irregular distribution of milk groups geographically [38]. Non-genetic factors that might contribute to variation in HMO contents are mother’s age, nutritional status, weight, body-mass index, and significant health issues of the mother [39].

In addition to natural causes described above (particularly genetic secretor status and lactation period) differences in reported HMO concentration are certainly also linked to varying inter-laboratory methodologies for glycan analysis [40]. Nevertheless, existing literature of HMO quantification represents a useful resource to determine the mean concentrations of individual HMO structures, and investigate their variation over the course of lactation. A previous systematic review by Thurl et al., provides knowledge on HMO amounts in human milk from mothers of known secretor status [41]. To date, no review has been performed to determine more robustly the most abundant HMOs observed globally in term human milk throughout lactation and their representative mean concentrations. In the present review, each included publication was regarded as an observational point with the central aim to make an estimation of the global HMO profile for pooled samples regardless of the individual variations caused by genetic and non-genetic factors. The authors decided on determining an overview on pooled milk samples instead of secretor and non-secretor samples given that the chosen objective was to determine a ranking of individual HMOs by global means across different milk phenotypes, regardless of individual variations and has included all relevant and reliable HMO concentration data identified.

References

- Hennet, T.; Borsig, L. Breastfed at Tiffany’s. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 508–518.

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; França, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C.; et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490.

- Le Huërou-Luron, I.; Blat, S.; Boudry, G. Breast- v. formula-feeding: Impacts on the digestive tract and immediate and long-term health effects. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23, 23–36.

- Hester, S.N.; Hustead, D.S.; Mackey, A.D.; Singhal, A.; Marriage, B.J. Is the macronutrient intake of formula-fed infants greater than breast-fed infants in early infancy? J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 891201.

- Urashima, T.; Saito, T.; Nakamura, T.; Messer, M. Oligosaccharides of milk and colostrum in non-human mammals. Glycoconj. J. 2001, 18, 357–371.

- Newburg, D.S.; Warren, C.D.; Chaturvedi, P.; Newburg, A.; Oftedal, O.T.; Ye, S.; Tilden, C.D. Milk oligosaccharides across species. Pediatr. Res. 1999, 45, 745.

- Albrecht, S.; Lane, J.A.; Mariño, K.V.; Al Busadah, K.A.; Carrington, S.D.; Hickey, R.M.; Rudd, P.M. A comparative study of free oligosaccharides in the milk of domestic animals. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1313–1328.

- Tao, N.; Wu, S.; Kim, J.; An, H.J.; Hinde, K.; Power, M.; Gagneux, P.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B. Evolutionary glycomics: Characterization of milk oligosaccharides in primates. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 1548–1557.

- Urashima, T.; Asakuma, S.; Leo, F.; Fukuda, K.; Messer, M.; Oftedal, O.T. The predominance of type I oligosaccharides is a feature specific to human breast milk. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 473S–482S.

- Gagneux, P.; Cheriyan, M.; Hurtado-Ziola, N.; van der Linden, E.C.M.B.; Anderson, D.; McClure, H.; Varki, A.; Varki, N.M. Human-specific regulation of α2–6-linked sialic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 48245–48250.

- Varki, A. Uniquely human evolution of sialic acid genetics and biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8939–8946.

- Bishop, J.R.; Gagneux, P. Evolution of carbohydrate antigens—Microbial forces shaping host glycomes? Glycobiology 2007, 17, 23R–34R.

- Jantscher-Krenn, E.; Aigner, J.; Reiter, B.; Köfeler, H.; Csapo, B.; Desoye, G.; Bode, L.; Van Poppel, M.N.M. Evidence of human milk oligosaccharides in maternal circulation already during pregnancy: A pilot study. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2018.

- Hirschmugl, B.; Brandl, W.; Csapo, B.; Van Poppel, M.; Köfeler, H.; Desoye, G.; Wadsack, C.; Jantscher-Krenn, E. Evidence of Human Milk Oligosaccharides in Cord Blood and Maternal-to-Fetal Transport across the Placenta. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2640.

- Jochum, M.; Seferovic, M.; Bode, L.; Vidaeff, A.; Aagaard, K.M. 91: Human milk oligosaccharides are present in midgestation amniotic fluid & associated with a sparse microbiome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, S74–S75.

- Brand-Miller, J.C.; McVeagh, P.; McNeil, Y.; Messer, M. Digestion of human milk oligosaccharides by healthy infants evaluated by the lactulose hydrogen breath test. J. Pediatr. 1998, 133, 95–98.

- Sakanaka, M.; Hansen, M.E.; Gotoh, A.; Katoh, T.; Yoshida, K.; Odamaki, T.; Yachi, H.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kurihara, S.; Hirose, J.; et al. Evolutionary adaptation in fucosyllactose uptake systems supports bifidobacteria-infant symbiosis. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw7696.

- Bezirtzoglou, E.; Tsiotsias, A.; Welling, G.W. Microbiota profile in feces of breast- and formula-fed newborns by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Anaerobe 2011, 17, 478–482.

- Garrido, D.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Kirmiz, N.; Davis, J.C.; Totten, S.M.; Lemay, D.; Ugalde, J.A.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Mills, D.A. A novel gene cluster allows preferential utilization of fucosylated milk oligosaccharides in Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum SC596. Sci.Rep. 2016, 6, 1–18.

- De Leoz, M.L.; Kalanetra, K.M.; Bokulich, N.A.; Strum, J.S.; Underwood, M.A.; German, J.B.; Mills, D.A.; Lebrilla, C.B. Human milk glycomics and gut microbial genomics in infant feces show a correlation between human milk oligosaccharides and gut microbiota: A proof-of-concept study. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 491–502.

- Pacheco, A.R.; Sperandio, V. Enteric pathogens exploit the microbiota-generated nutritional environment of the gut. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 1–13.

- Sela, D.A.; Mills, D.A. The marriage of nutrigenomics with the microbiome: The case of infant-associated bifidobacteria and milk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 697S–703S.

- Turroni, F.; Milani, C.; Duranti, S.; Ferrario, C.; Lugli, G.A.; Mancabelli, L.; Van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. Bifidobacteria and the infant gut: An example of co-evolution and natural selection. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 103–118.

- Turroni, F.; Ribbera, A.; Foroni, E.; Van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. Human gut microbiota and bifidobacteria: From composition to functionality. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2008, 94, 35–50.

- Chichlowski, M.; De Lartigue, G.; German, J.B.; Raybould, H.E.; Mills, D.A. Bifidobacteria isolated from infants and cultured on human milk oligosaccharides affect intestinal epithelial function. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 55, 321–327.

- Mezoff, E.A.; Hawkins, J.A.; Ollberding, N.J.; Karns, R.; Morrow, A.L.; Helmrath, M.A. The human milk oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose augments the adaptive response to extensive intestinal. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2016, 310, G427–G438.

- Tonon, K.M.; De Morais, M.B.; Abrão, A.C.F.V.; Miranda, A.; Morais, T.B. Maternal and infant factors associated with human milk oligosaccharides concentrations according to secretor and lewis phenotypes. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1358.

- Wickramasinghe, S.; Pacheco, A.R.; Lemay, D.; Mills, D.A. Bifidobacteria grown on human milk oligosaccharides downregulate the expression of inflammation-related genes in Caco-2 cells. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 1–12.

- Craft, K.M.; Townsend, S.D. Mother knows best: Deciphering the antibacterial properties of human milk oligosaccharides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 760–768.

- Urashima, T. Indigenous oligosaccharides in bovine milk. Agriculture 2011, 3, 241–273.

- Totten, S.M.; Wu, L.D.; Parker, E.A.; Davis, J.C.C.; Hua, S.; Stroble, C.; Ruhaak, L.R.; Smilowitz, J.T.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B. Rapid-throughput glycomics applied to human milk oligosaccharide profiling for large human studies. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 7925–7935.

- Chen, X. Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOS): Structure, Function, and Enzyme-Catalyzed Synthesis, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 72.

- Thurl, S.; Henker, J.; Siegel, M.; Tovar, K.; Sawatzki, G. Detection of four human milk groups with respect to Lewis blood group dependent oligosaccharides. Glycoconj. J. 1997, 14, 795–799.

- Oriol, R.; Le Pendu, J.; Mollicone, R. Genetics of ABO, H, Lewis, X and related antigens. Vox Sang. 1986, 51, 161–171.

- Morrow, A.L.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Altaye, M.; Jiang, X.; Guerrero, M.L.; Meinzen-Derr, J.K.; Farkas, T.; Chaturvedi, P.; Pickering, L.K.; Newburg, D.S. Human milk oligosaccharides are associated with protection against diarrhea in breast-fed infants. J. Pediatr. 2004, 145, 297–303.

- Erney, R.M.; Malone, W.T.; Skelding, M.B.; Marcon, A.A.; Kleman–Leyer, K.M.; O’Ryan, M.L.; Ruiz–Palacios, G.; Hilty, M.D.; Pickering, L.K.; Prieto, P. Variability of human milk neutral oligosaccharides in a diverse population. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2000, 30, 181–192.

- McGuire, M.K.; Meehan, C.L.; McGuire, M.A.; Williams, J.E.; Foster, J.; Sellen, D.W.; Kamau-Mbuthia, E.W.; Kamundia, E.W.; Mbugua, S.; Moore, S.E.; et al. What’s normal? Oligosaccharide concentrations and profiles in milk produced by healthy women vary geographically. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 1086–1100.

- Castanys-Muñoz, E.; Martin, M.J.; Prieto, P.A. 2′-fucosyllactose: An abundant, genetically determined soluble glycan present in human milk. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 773–789.

- Seferovic, M.D.; Mohammad, M.; Pace, R.M.; Engevik, M.; Versalovic, J.; Bode, L.; Haymond, M.; Aagaard, K.M. Maternal diet alters human milk oligosaccharide composition with implications for the milk metagenome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–18.

- Van Leeuwen, S.S. Challenges and pitfalls in human milk oligosaccharide analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2684.

- Thurl, S.; Munzert, M.; Boehm, G.; Matthews, C.; Stahl, B. Systematic review of the concentrations of oligosaccharides in human milk. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 920–933.