A major challenge for effective treatment of TNBC is to eliminate CSCs. CSCs have the capacity to self-renew, differentiate, dedifferentiate, and hibernate

[7], capable of initiating new tumors to cause disease relapse

[8][9]. Although conventional chemotherapeutic drugs effectively suppress bulk tumor cells, they are ineffective in inhibiting CSCs, and even enrich CSCs following treatment

[3][4][5]. CSCs in TNBC are heterogeneous, interconvertible, and respond to chemotherapy differently

[10][11][12][13].

2. Overview of Epithelial and Mesenchymal CSCs in Breast Cancer

CSCs are a small population residing within tumors. They exhibit stem cell-like properties, such as self-renewal, differentiation, dedifferentiation, trans-differentiation, symmetric/asymmetric division, and quiescence

[14]. CSCs have been found to exist in different types of solid tumors and are at the apex of the cellular hierarchy in tumors, capable of maintaining CSC pools and giving rise to non-CSC bulk tumor cells to promote disease progression

[15].

Al Hajj et al. made the first demonstration that the fractionated CD44

+/CD24

− subpopulation from breast cancer patients exhibited a 100-fold greater capacity to form tumors (i.e., tumorigenicity) compared to those unsorted cells after transplantation into mammary pad of immunodeficient mice

[16]. CD44 (cluster of differentiation 44) is a class I transmembrane glycoprotein which acts as a receptor for hyaluronic acid and is associated with modulating mesenchymal-like processes such as cell adhesion, invasion, and migration

[17][18]. In contrast, CD24 (cluster of differentiation 24) is associated with carbohydrate metabolism and epithelial-like breast cancer cells

[19]. CD44

+/CD24

− CSCs are associated with a mesenchymal-like phenotype that is highly metastatic/invasive and possesses a greater tumorigenesis capacity

[18].

Another marker for breast CSCs is aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH), which is frequently used as a marker for hematopoietic stem cells

[20]. ALDH are comprised of 19 isomers which catalyze the oxidation of aldehydes and convert aldehydes to carboxylic acids, important for cellular detoxification after exposure to chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide)

[21]. High ALDH expression has been associated with CSCs in a wide variety of cancers, including breast cancer

[21]. The fractionated ALDH

+ cells from patients with breast tumor possessed greater tumorigenic potentials, regenerating new tumors with as few as 1500 cells. In contrast, ALDH

− cells were not capable of forming tumors even after injection of 50,000 cells

[22]. Interestingly, ALDH is predominantly expressed in epithelium tissues in the brain, liver, kidneys, and breast

[21]. ALDH

+ breast cancer CSCs exhibit an epithelial-like phenotype

[11].

In a landmark study, Liu et al. reported that CD44

+/CD24

− CSCs resided at the edge of the breast tumor with low expression of E-cadherin but high expression of vimentin and ZEB1 (Zinc Finger E-Box Binding Homeobox 1), exhibiting a mesenchymal, migratory, and invasive phenotype

[11]. In contrast, ALDH

+ CSCs resided within the core of the tumor with high expression of E-cadherin but low expression of vimentin and ZEB1, exhibiting an epithelial phenotype

[11]. This study demonstrated that M (mesenchymal, CD44

+/CD24

−) and E (epithelial, ALDH+) CSCs were distinct populations with different patterns in tumor distribution, gene expression, proliferation, and quiescence, suggesting different functionalities of these two CSC subpopulations

[11]. E and M CSCs existed in all breast cancer subtypes, but their proportions were varied. Basal TNBC cell lines were enriched with both E and M CSCs compared to their luminal breast cancer counterparts

[11].

E and M CSCs were found to be interconvertible. Liu et al. demonstrated that fractionated M or E CSCs from breast cancer cell lines gradually reconstituted the heterogeneous tumor population (bulk, CD44

+/CD24

−, and ALDH

+ tumor cells)

[11]. Together, these findings support the existence of distinct mesenchymal and epithelial CSCs within breast tumors, and demonstrate that these populations are plastic, capable of reconstituting other CSC and non-CSC populations

[11].

Cancer metastasis is responsible for 90% of cancer-related deaths

[23]. Epithelial to mesenchymal (EMT) transition is a biological process, which facilitates tumor cell dissociation, migration, and metastasis

[24]. At the core of tumor, when cancer cells are undergoing EMT, epithelial cells gain a mesenchymal phenotype (e.g., loss of E-cadherin, cytokeratin, and claudin while acquiring N-cadherin and vimentin). This change reduced cell-cell adhesion but increased migration and invasion of cancer cells, moving from the tumor core to the edge

[24]. M CSCs at the edge of the tumor invade the surrounding tissue, translocate into the bloodstream, and then migrate to different tissues

[11][25]. Upon arriving at a suitable secondary location, the M CSCs convert into an E CSC state, capable of promoting angiogenesis and growing quickly in hypoxic conditions

[25]. Conventionally, EMT is thought to facilitate metastasis, while MET is critical for secondary tumor formation. Within the secondary tumor, the E CSC population can differentiate into bulk tumor cells, self-renew to maintain its population, and convert into M CSCs to repeat the cycle

[25].

Although the EMT/MET model for metastasis is well-studied and accepted to date, histological evidence in patient tumor samples has not been proved

[26]. Furthermore, two recent studies have challenged the role of EMT/MET model in cancer metastasis

[27][28]. Using a loss-of-function approach, Zheng et al. knocked out Twist or Snail (two critical EMT inducers) using Cre-recombinase in a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma mouse model in order to suppress EMT. However, the number of traced metastatic circulating tumor cells was not changed following Twist knockout. Additionally, metastatic tumor cells in various organs were negative for a mesenchymal marker (α-smooth muscle actin) compared to the controls, indicating that EMT was dispensable for metastasis

[27].

Another study by Fischer et al. employed an EMT lineage-tracking system using a mesenchymal-specific promoter to track whether the metastatic lung cancer cells underwent EMT

[28]. They found that breast cancer-lung metastasis maintained their epithelial phenotype, indicating that EMT was dispensable for metastasis

[28].

There has been debate over the aforementioned studies

[29][30]. For the Twist and Snail knockout studies used in the report of Zheng et al.

[27], α-smooth muscle actin is not considered a reliable marker for EMT monitoring in the particular mouse model

[29]. Additionally, after Twist and Snail knockout, unaltered metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma mouse cells may be due to the redundancies within the EMT process

[29].

Another research group found that the Fsp1-cre transgene used in the manuscript of Fischer et al. may not be a critical modulator of EMT, as Fsp1 knockout mice are capable of undergoing all stages of EMT

[30][31]. Fsp1 is also not expressed universally in carcinoma cells that have undergone EMT

[30]. Additionally, the vimentin-Cre tracing marker used in Fischer et al. studies is only weakly expressed in carcinoma cells undergoing EMT, while tumor-associated stromal cells highly expressed vimentin, indicating a potential challenge for the lineage tracing system used

[30].

These rebuttals highlight the complicated nature of EMT/MET in metastasis and secondary tumor formation. Fischer et al. replied to the rebuttal, defending their usage of vimentin and Fsp1 promoters as indicators of EMT. Additionally, Fischer et al. further demonstrated the fidelity and efficacy of the Fsp1-Cre RFP+ to GFP+ EMT model and showed that the GFP+ EMT cells constitute only 4.46 ± 1.0% of the total primary tumor cells in the Vimentin–Cre model. Importantly, none of the metastases observed were derived from these GFP+ EMT cells. Based on the specificity of their models, Fischer et al. argued that EMT is not required for metastasis

[32].

Indeed, increasing evidence supports that tumor cells do not need to undergo a complete EMT/MET shift for metastasis and formation of secondary tumors

[25][33][34]. Additionally, the identification of CSCs expressing both M and E markers suggests the existence of a hybrid E/M CSC phenotype

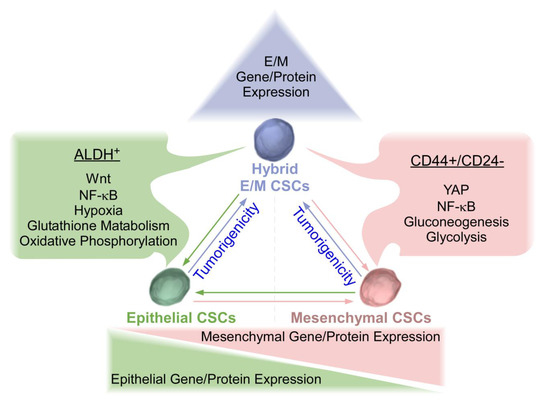

[11][18]. Hybrid CSCs are cells in the process of EMT/MET. This hybrid state may facilitate mobility, survival, and reconstitution of secondary tumor. Hybrid CSCs have been shown to possess greater tumorigenicity and metastatic potential in comparison with complete EMT or MET CSC counterparts (

Figure 1)

[22][25][34]. Of note, different CSC populations can interconvert, which may just represent different epigenetic states within the same clonal population, warranting further studies. Emerging single-cell technologies (e.g., single-cell RNA sequencing, single-nucleus RNA-sequencing) provide a new opportunity to profile individual cells within tumors and to study tumor heterogeneity and metastasis at single-cell resolution

[35]. For example, single-nucleus sequencing of breast cancers revealed that copy number evolution occurred in short bursts early in tumor evolution, whereas point mutations evolved gradually over time to produce more extensive clonal diversity

[36]. Harnessing the power of single-cell assessment will lead to great insights into the properties of EMT, MET, and hybrid CSCs.

Figure 1. Epithelial, Mesenchymal, and Hybrid triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cancer stem cells (CSCs). TNBC mesenchymal (M) CSCs are characterized by CD44+/CD24− with elevated levels of Yes associated protein (YAP), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), and enhanced gluconeogenesis and glycolysis. Conversely, TNBC epithelial (E) CSCs are characterized by ALDH+ with elevated levels of Wnt, NF-κB, hypoxia, enhanced glutathione metabolism, and oxidative phosphorylation. Epithelial and mesenchymal CSCs exhibited plasticity and were interconvertible. Recent studies have revealed that hybrid E/M CSCs are more tumorigenic than complete E and M counterparts and may be capable of differentiating into complete epithelial or mesenchymal CSCs. Plasticity amongst three states of CSCs needs to be considered for the development of effective therapeutic strategies for TNBC.

3. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Breast Cancer and TNBC and Its Association with Epithelial CSCs

Wnt signaling pathways are characterized into the canonical or β-catenin dependent pathway, and the non-canonical or β-catenin independent pathway. More focus has been on the canonical pathway in the field. Wnt/β-catenin canonical signaling is a highly conserved developmental pathway. It regulates self-renewal of hematopoietic, intestinal, and embryonic stem cells

[37]. Wnt signaling is also essential for self-renewal and differentiation of mammary stem cell/progenitor cells

[38]. Dysregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been shown to be highly expressed in TNBC and inversely correlated with poor patient survival, promoting CSC enrichment, chemoresistance, and metastasis. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is also associated with E CSC expansion

[39][40][41][42][43]. Interestingly, Wnt/β-catenin mutations commonly found in other cancer types are rarely found in breast cancer

[44].

Canonic Wnt activation contributes to chemoresistance, and chemotherapy enhances Wnt signaling in breast cancer

[3]. It has been shown that WNT10B signal axis was elevated in TNBC and correlated with chemoresistance and poor patient prognosis

[45]. HMGA2 (High Mobility Group AT-Hook 2, a direct target of WNT10B) is linked with EZH2 (Enhancer of Zeste 2, a methyltransferase which epigenetically modulates chromatin) activity, and directly interacted with β-catenin to stimulate Wnt activity

[46][47]. The WNT10B/β-catenin/HMGA2/EZH2 cascade is expressed in TNBC and associated with increased rates of metastasis and decreased recurrence-free survival by 2.4-fold

[45]. Ayachi et al. further revealed an autoregulatory loop between EZH2 and HMGA2 in TNBC cells

[48]. HMGA-EZH2 protein-protein interactions were required for CBP (CREB-binding protein) K49 acetylation of β-catenin to modulate Wnt activity

[48]. Moreover, both HMGA2/EZH2 promoted EMT in TNBC, and deletion of either one significantly reduced tumor growth and metastasis without affecting tumorigenicity

[48]. Using TNBC patient derived xenografts (PDX), it was demonstrated that Wnt signaling was highly activated in both chemoresistant and naïve TNBC PDX tumors. Furthermore, all PDX tumors were sensitive to the treatment with small molecule inhibitor ICG-001 or PRI-724. ICG-001 and PRI-724 are distinct chemical entities, albeit both are CBP/β-catenin antagonists. Only PRI-724 has been tested in the clinic

[48], and was demonstrated to be safe and tolerable to patients

[49].

Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been associated with E CSCs. Wnt is more highly expressed in E ALDH

+ CSC populations than in M CD44

+/CD24

− CSCs

[50][51]. Moreover, E CSCs are more sensitive to Wnt inhibition than M CSCs

[50][52]. Domenici et al. recently found that Sox9 (Sry-related HMG box 9, an essential modulator of mammary gland development) transcription factor is a key modulator of self-renewal of breast luminal progenitor cells. The expression levels of Sox9 were found to be higher in breast tumors and the highest in TNBC samples, with the fractionated ALDH

+ breast tumor cells possessing higher levels of Sox9 mRNA

[53]. Sox9 is a poor prognostic indicator and is strongly associated with Wnt signaling via LRP6 (Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6) and TCF4 (Transcription Factor 4) in breast cancer

[54]. Inhibition of Sox9 reduced tumorigenicity and E CSC population, and sensitized breast cancer cells to therapeutic intervention

[53].

Interestingly, latency competent breast cancer cells (LCBCC, cancer cells that can reseed organs with latent metastasis) have been found to maintain a stem cell-like state and express Sox2 and Sox9 transcription factors. Surveillance of natural killer (NK) cells prevents these LCBCC from infiltrating into organs and expanding. However, the LCBCC cells can downregulate NK cell activators and develop resistance. LCBCC express high levels of DKK1 (Dickkopf-related protein 1) to inhibit Wnt signaling and enforce a quiescent state. Knockdown of DKK1 increases metastatic growth, thus linking Wnt signaling with long-term quiescence in disseminated cancer cells that cause latent metastasis and relapse

[55]. This adds an additional layer of complexity to the role of canonical Wnt signaling in breast cancer CSCs. Furthermore, different from the role of canonical Wnt pathway in E CSCs, non-canonical Wnt signals have recently been shown to promote invasion, survival, and metastasis of CSCs, and is likely important in M phenotypic TNBC CSCs

[43]. Further studies of the roles of canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways in CSC are required.

Combination of canonical Wnt inhibitors with conventional chemotherapeutic agents seems to be an attractive approach for TNBC treatment. Synergistic reduction of tumor growth and metastasis has been observed when chemoresistant TNBC PDX tumors were treated with doxorubicin and the Wnt inhibitor ICG-001/PRI-724

[48][56]. Active and interventional clinical trials in Clinicaltrials.gov database for the treatment of patients with TNBC are summarized in

Table 1. These potential Wnt modulators/inhibitors seem to be safe for the usage in clinic and have been demonstrated to suppress the Wnt signaling pathway in preclinical studies. Further studies will be needed to determine their clinical efficacy in combination with other inhibitors and chemotherapeutic drugs, as well as underlying mechanisms.

Table 1. Potential Wnt Inhibitors Tested in TNBC Clinical Trials.

| Inhibitor |

Clinical Trial Number |

Mechanism |

References |

| RX-5902 |

NCT02003092 |

Inhibits phosphorylated p68 RNA helicase preventing nuclear β-catenin translocation and Wnt signaling |

[57][58] |

| CB-839 |

NCT03057600 |

Glutaminase Inhibitor (GSL1). GLS1 has been found to promote stemness via reactive oxygen species/Wnt/ β-catenin signaling |

[59] |

| Eribulin mesylate |

NCT02513472 |

Inhibitor of microtubule dynamics and demonstrated Wnt-related gene suppressive properties |

[60] |

| Selinexor |

NCT02402764 |

Selective inhibitor of nuclear export (SINE) that blocks XPO1 leading to forced nuclear retention of major tumor suppressor proteins reducing β-catenin |

[61] |

| Sorafenib |

NCT02624700 |

Tyrosine protein kinase inhibitor and reduces β-catenin and Wnt signaling |

[62] |

| Cetuximab |

NCT01097642 |

Monoclonal antibody which binds to and inhibits EGFR. Also Inhibits of MAPK which leads to inhibition of β-catenin nuclear activity. |

[63] |

| Indomethacin |

NCT02950259 |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug which inhibits prostaglandins which is capable of suppressing β-catenin expression. |

[64] |

| Bicalutamide |

NCT03090165 |

Androgen antagonist preventing Wnt/β-catenin signaling |

[65] |