| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Michał Świątczak | + 5530 word(s) | 5530 | 2021-07-19 03:55:37 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 5509 | 2021-08-19 03:46:18 | | |

Video Upload Options

Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is a genetic disease leading to excessive iron absorption, its accumulation, and oxidative stress induction causing different organ damage, including the heart. The process of cardiac involvement is slow and lasts for years. Cardiac pathology manifests as an impaired diastolic function and cardiac hypertrophy at first and as dilatative cardiomyopathy and heart failure with time. From the moment of heart failure appearance, the prognosis is poor. Therefore, it is crucial to prevent those lesions by upfront therapy at the preclinical phase of the disease. The most useful diagnostic tool for detecting cardiac involvement is echocardiography. However, during an early phase of the disease, when patients do not present severe abnormalities in serum iron parameters and severe symptoms of other organ involvement, heart damage may be overlooked due to the lack of evident signs of cardiac dysfunction. Considerable advancement in echocardiography, with particular attention to speckle tracking echocardiography, allows detecting discrete myocardial abnormalities and planning strategy for further clinical management before the occurrence of substantial heart damage.

1. Introduction

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Iron Regulation

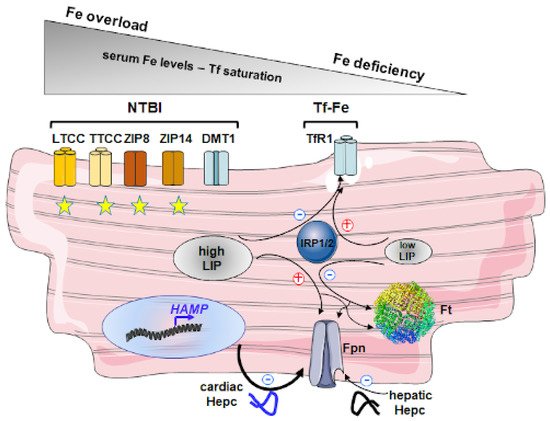

2.1. Outline of Cellular Iron Metabolism

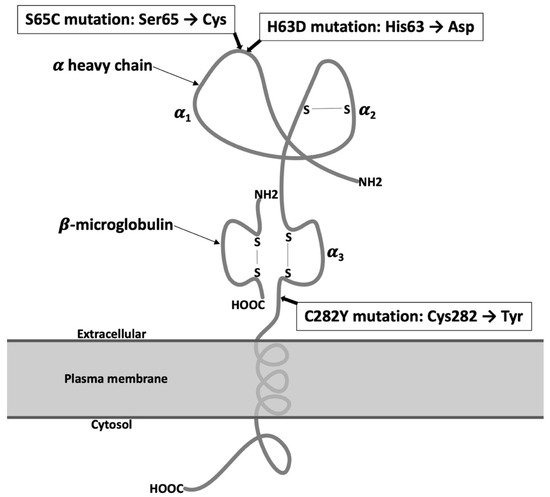

2.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Iron Overload in HH

3. Mechanism of Cardiac Damage in HH

3.1. Regulation of Iron Metabolism in Cardiomyocytes

3.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Cardiac Damage in HH

3.3. Cardiac Involvement in HH

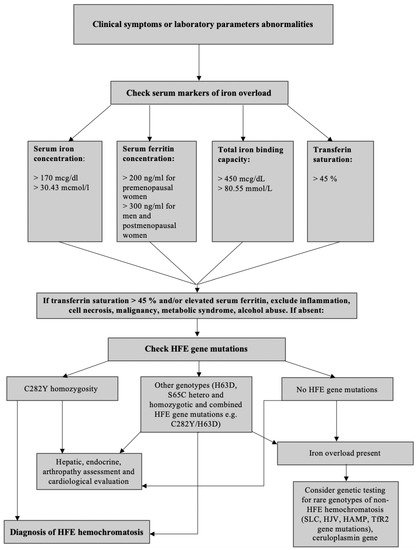

4. Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic of HH

Laboratory Diagnostics

5. Cardiological Diagnosis

5.1. Electrocardiography

5.2. Standard Echocardiography

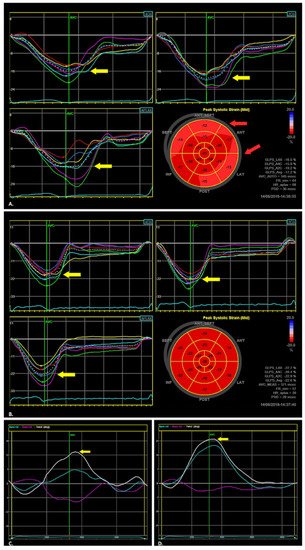

5.3. Two-Dimensional Speckle Tracking Echocardiography (2D STE)

| Cardiac Diagnostic Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|

| Method | Characteristics | |

| Electrocardiography | Possible features of hypertrophy and nonspecific ST-T changes in the long-lasting HH | |

| Echocardiography | Standard echocardiography (abnormalities possible to be discovered in the long-lasting HH) | LV hypertrophy LA enlargement Diastolic LV dysfunction Systolic LV dysfunction |

| Two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography (abnormalities possible to be discovered at the early stages of HH) |

Lower values of apical LV rotation Lower values of basal LV rotation Lower global longitudinal strain of LV |

|

| Three-dimensional echocardiography * abnormalities possible to be discovered at the early stages of HH ** abnormalities possible to be discovered in the long-lasting HH |

Higher LV thickness (*/**) Higher LV mass (*/**) Higher LV long axis length (*/**) Higher LA diameter and volume (*/**) Lower LV ejection fraction (*) |

|

| Cardiac magnetic resonance | Reduced T2 relaxation time | |

| Biopsy | Iron clusters among healthy tissue (*) Limitations: high risk of false-negative results |

|

| * limited to unclear situations that require distinguish from other causes of heart failure or infiltrative diseases | ||

5.4. Three-Dimensional (3D) Real-Time Echocardiography

5.5. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR)

5.6. Biopsy

6. Treatment of HH and ITS Influence on the Cardiac Function

References

- Gulati, V.; Harikrishnan, P.; Palaniswamy, C.; Aronow, W.S.; Jain, D.; Frishman, W.H. Cardiac involvement in hemochromatosis. Cardiol. Rev. 2014, 22, 56–68.

- Sikorska, K.; Bielawski, K.; Romanowski, T.; Stalke, P. Hemochromatoza dziedziczna -najczęstsza choroba genetyczna człowieka (Hereditary hemochromatosis: The most frequent inherited human disease). Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 2006, 60, 667–676.

- Swinkels, D.W.; Janssen, M.C.; Bergmans, J.; Marx, J.J. Hereditary hemochromatosis: Genetic complexity and new diagnostic approaches. Clin. Chem. 2006, 52, 950–968.

- McLaren, G.D.; Gordeuk, V.R. Hereditary hemochromatosis: Insights from the hemochromatosis and iron overload screening (HEIRS) study. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol Educ. Program. 2009, 2009, 195–206.

- Camaschella, C.; Roetto, A.; Calì, A.; De Gobbi, M.; Garozzo, G.; Carella, M.; Majorano, N.; Totaro, A.; Gasparini, P. The gene TFR2 is mutated in a new type of haemochromatosis mapping to 7q22. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 14–15.

- Roetto, A.; Papanikolaou, G.; Politou, M.; Alberti, F.; Girelli, D.; Christakis, J.; Loukopoulos, D.; Camaschella, C. Mutant antimicrobial peptide hepcidin is associated with severe juvenile hemochromatosis. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 21–22.

- Pietrangelo, A. The ferroportin disease. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2004, 32, 131–138.

- Strohmeyer, G.; Niederau, C.; Stremmel, W. Survival and causes of death in hemochromatosis. Observations in 163 patients. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988, 526, 245–257.

- Niederau, C.; Fischer, R.; Sonnenberg, A.; Stremmel, W.; Trampisch, H.J.; Strohmeyer, G. Survival and causes of death in cirrhotic and in noncirrhotic patients with primary hemochromatosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 313, 1256–1262.

- Vigorita, V.J.; Hutchins, G.M. Cardiac conduction system in hemochromatosis: Clinical and pathologic features of six patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 1979, 44, 418–423.

- Buja, L.M.; Roberts, W.C. Iron in the heart. Etiology and clinical significance. Am. J. Med. 1971, 51, 209–221.

- Stickel, F.; Osterreicher, C.H.; Datz, C.; Ferenci, P.; Wölfel, M.; Norgauer, W.; Kraus, M.R.; Wrba, F.; Hellerbrand, C.; Schuppan, D.; et al. Prediction of progression to cirrhosis by a glutathione S-transferase P1 polymorphism in subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1835–1840.

- Quinlan, G.J.; Evans, T.W.; Gutteridge, J.M. Iron and the redox status of the lungs. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 1306–1313.

- Tsushima, R.G.; Wickenden, A.D.; Bouchard, R.A.; Oudit, G.Y.; Liu, P.P.; Backx, P.H. Modulation of iron uptake in heart by L-type Ca2+ channel modifiers: Possible implications in iron overload. Circ. Res. 1999, 84, 1302–1309.

- Candell-Riera, J.; Lu, L.; Serés, L.; González, J.B.; Batlle, J.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; García-del-Castillo, H.; Soler-Soler, J. Cardiac hemochromatosis: Beneficial effects of iron removal therapy. An echocardiographic study. Am. J. Cardiol. 1983, 52, 824–829.

- Palka, P.; Macdonald, G.; Lange, A.; Burstow, D.J. The role of Doppler left ventricular filling indexes and Doppler tissue echocardiography in the assessment of cardiac involvement in hereditary hemochromatosis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2002, 15, 884–890.

- Davidsen, E.S.; Omvik, P.; Hervig, T.; Gerdts, E. Left ventricular diastolic function in patients with treated haemochromatosis. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2009, 43, 32–38.

- Dabestani, A.; Child, J.S.; Perloff, J.K.; Figueroa, W.G.; Schelbert, H.R.; Engel, T.R. Cardiac abnormalities in primary hemochromatosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988, 526, 234–244.

- Finch, S.C.; Finch, C.A. Idiopathic hemochromatosis, an iron storage disease. A. Iron metabolism in hemochromatosis. Medicine 1955, 34, 381–430.

- Passen, E.L.; Rodriguez, E.R.; Neumann, A.; Tan, C.D.; Parrillo, J.E. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Cardiac hemochromatosis. Circulation 1996, 94, 2302–2303.

- Tauchenová, L.; Křížová, B.; Kubánek, M.; Fraňková, S.; Melenovský, V.; Tintěra, J.; Kautznerová, D.; Malušková, J.; Jirsa, M.; Kautzner, J. Successful treatment of iron-overload, cardiomyopathy in hereditary hemochromatosis with deferoxamine and deferiprone. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 1574.e1–1574.e3.

- Rivers, J.; Garrahy, P.; Robinson, W.; Murphy, A. Reversible cardiac dysfunction in hemochromatosis. Am. Heart J. 1987, 113, 216–217.

- Easley, R.M., Jr.; Schreiner, B.F., Jr.; Yu, P.N. Reversible cardiomyopathy associated with hemochromatosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1972, 287, 866–867.

- Rahko, P.S.; Salerni, R.; Uretsky, B.F. Successful reversal by chelation therapy of congestive cardiomyopathy due to iron overload. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1986, 8, 436–440.

- Gammella, E.; Recalcati, S.; Rybinska, I.; Buratti, P.; Cairo, G. Iron-induced damage in cardiomyopathy: Oxidative-dependent and independent mechanisms. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2015, 2015, 230182.

- Wilkinson, N.; Pantopoulos, K. The IRP/IRE system in vivo: Insights from mouse models. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 176.

- Kakhlon, O.; Cabantchik, Z.I. The labile iron pool: Characterization, measurement, and participation in cellular processes(1). Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 1037–1046.

- Richardson, D.R.; Ponka, P. The molecular mechanisms of the metabolism and transport of iron in normal and neoplastic cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1331, 1–40.

- Beaumont, C.; Canonne-Hergaux, F. Erythrophagocytose et recyclage du fer héminique dans les conditions normales et pathologiques; régulation par l’hepcidine [Erythrophagocytosis and recycling of heme iron in normal and pathological conditions; regulation by hepcidin]. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2005, 12, 123–130.

- Gunshin, H.; Mackenzie, B.; Berger, U.V.; Gunshin, Y.; Romero, M.F.; Boron, W.F.; Nussberger, S.; Gollan, J.L.; Hediger, M.A. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature 1997, 388, 482–488.

- Brissot, P.; Ropert, M.; le Lan, C.; Loréal, O. Non-transferrin bound iron: A key role in iron overload and iron toxicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 403–410.

- Schaer, D.J.; Vinchi, F.; Ingoglia, G.; Tolosano, E.; Buehler, P.W. Haptoglobin, hemopexin, and related defense pathways-basic science, clinical perspectives, and drug development. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 415.

- Brissot, P.; Pietrangelo, A.; Adams, P.C.; de Graaff, B.; McLaren, C.E.; Loréal, O. Haemochromatosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18016.

- Schaer, D.J.; Vinchi, F.; Ingoglia, G.; Tolosano, E.; Buehler, P.W. GNPAT p.D519G is independently associated with markedly increased iron stores in HFE p.C282Y homozygotes. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2017, 63, 15–20.

- Feder, J.N.; Gnirke, A.; Thomas, W.; Tsuchihashi, Z.; Ruddy, D.A.; Basava, A.; Dormishian, F.; Domingo, R., Jr.; Ellis, M.C.; Fullan, A.; et al. A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Nat. Genet. 1996, 13, 399–408.

- Pigeon, C.; Ilyin, G.; Courselaud, B.; Leroyer, P.; Turlin, B.; Brissot, P.; Loréal, O. A new mouse liver-specific gene, encoding a protein homologous to human antimicrobial peptide hepcidin, is overexpressed during iron overload. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 7811–7819.

- Nicolas, G.; Bennoun, M.; Devaux, I.; Beaumont, C.; Grandchamp, B.; Kahn, A.; Vaulont, S. Lack of hepcidin gene expression and severe tissue iron overload in upstream stimulatory factor 2 (USF2) knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 8780–8785.

- Bridle, K.R.; Frazer, D.M.; Wilkins, S.J.; Dixon, J.L.; Purdie, D.M.; Crawford, D.H.; Subramaniam, V.N.; Powell, L.W.; Anderson, G.J.; Ramm, G.A.; et al. Disrupted hepcidin regulation in HFE-associated haemochromatosis and the liver as a regulator of body iron homoeostasis. Lancet 2003, 361, 669–673.

- Xu, W.; Barrientos, T.; Mao, L.; Rockman, H.A.; Sauve, A.A.; Andrews, N.C. Lethal cardiomyopathy in mice lacking transferrin receptor in the heart. Cell. Rep. 2015, 13, 533–545.

- Lakhal-Littleton, S.; Wolna, M.; Carr, C.A.; Miller, J.J.; Christian, H.C.; Ball, V.; Santos, A.; Diaz, R.; Biggs, D. Cardiac ferroportin regulates cellular iron homeostasis and is important for cardiac function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3164–3169.

- Lakhal-Littleton, S.; Wolna, M.; Chung, Y.J.; Christian, H.C.; Heather, L.C.; Brescia, M.; Ball, V.; Diaz, R.; Santos, A.; Biggs, D.; et al. An essential cell-autonomous role for hepcidin in cardiac iron homeostasis. eLife 2016, 5, e19804.

- Haddad, S.; Wang, Y.; Galy, B.; Korf-Klingebiel, M.; Hirsch, V.; Baru, A.M.; Rostami, F.; Reboll, M.R.; Heineke, J.; Flögel, U.; et al. Iron-regulatory proteins secure iron availability in cardiomyocytes to prevent heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 362–372.

- Gordan, R.; Wongjaikam, S.; Gwathmey, J.K.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Xie, L.H. Involvement of cytosolic and mitochondrial iron in iron overload cardiomyopathy: An update. Heart Fail Rev. 2018, 23, 801–816.

- Chattipakorn, N.; Kumfu, S.; Fucharoen, S.; Chattipakorn, S. Calcium channels and iron uptake into the heart. World J. Cardiol. 2011, 3, 215–218.

- Knutson, M. Non-transferrin-mediated iron delivery. Blood 2016, 128, SCI-22.

- Drakesmith, H.; Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Ironing out ferroportin. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 777–787.

- Harrison, P.M.; Arosio, P. The ferritins: Molecular properties, iron storage function and cellular regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1996, 1275, 161–203.

- Boyd, D.; Vecoli, C.; Belcher, D.M.; Jain, S.K.; Drysdale, J.W. Structural and functional relationships of human ferritin H and L chains deduced from cDNA clones. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 11755–11761.

- Gryzik, M.; Srivastava, A.; Longhi, G.; Bertuzzi, M.; Gianoncelli, A.; Carmona, F.; Poli, M.; Arosio, P. Expression and characterization of the ferritin binding domain of Nuclear Receptor Coactivator-4 (NCOA4). Biochim. Biophys Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 2710–2716.

- Santana-Codina, N.; Mancias, J.D. The role of NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in health and disease. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 114.

- Lakhal-Littleton, S. Cardiomyocyte hepcidin: From intracellular iron homeostasis to physiological function. Vitam. Horm. 2019, 110, 189–200.

- Sumneang, N.; Siri-Angkul, N.; Kumfu, S.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N. The effects of iron overload on mitochondrial function, mitochondrial dynamics, and ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 680, 108241.

- Hentze, M.W.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Galy, B.; Camaschella, C. Two to tango: Regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 2010, 142, 24–38.

- Merle, U.; Fein, E.; Gehrke, S.G.; Stremmel, W.; Kulaksiz, H. The iron regulatory peptide hepcidin is expressed in the heart and regulated by hypoxia and inflammation. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 2663–2668.

- Zhang, H.; Zhabyeyev, P.; Wang, S.; Oudit, G.Y. Role of iron metabolism in heart failure: From iron deficiency to iron overload. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1925–1937.

- Murphy, C.J.; Oudit, G.Y. Iron-overload cardiomyopathy: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Card. Fail. 2010, 16, 888–900.

- Sukumaran, A.; Chang, J.; Han, M.; Mintri, S.; Khaw, B.A.; Kim, J. Iron overload exacerbates age-associated cardiac hypertrophy in a mouse model of hemochromatosis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5756.

- Salonen, J.T.; Nyyssönen, K.; Korpela, H.; Tuomilehto, J.; Seppänen, R.; Salonen, R. High stored iron levels are associated with excess risk of myocardial infarction in eastern Finnish men. Circulation 1992, 86, 803–811.

- Mestroni, L.; Rocco, C.; Gregori, D.; Sinagra, G.; Di Lenarda, A.; Miocic, S.; Vatta, M.; Pinamonti, B.; Muntoni, F.; Caforio, A.L.; et al. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy: Evidence for genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity. heart muscle disease study group. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 1999, 34, 181–190.

- Mahon, N.G.; Coonar, A.S.; Jeffery, S.; Coccolo, F.; Akiyu, J.; Zal, B.; Houlston, R.; Levin, G.E.; Baboonian, C.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. Haemochromatosis gene mutations in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart 2000, 84, 541–547.

- Olynyk, J.K.; Trinder, D.; Ramm, G.A.; Britton, R.S.; Bacon, B.R. Hereditary hemochromatosis in the post-HFE era. Hepatology 2008, 48, 991–1001.

- Anderson, L.J.; Westwood, M.A.; Holden, S.; Davis, B.; Prescott, E.; Wonke, B.; Porter, J.B.; Walker, J.M.; Pennell, D.J. Myocardial iron clearance during reversal of siderotic cardiomyopathy with intravenous desferrioxamine: A prospective study using T2* cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 127, 348–355.

- Świątczak, M.; Sikorska, K.; Raczak, G.; Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L. Nonroutine use of 2-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography and fatigue assessment to monitor the effects of therapeutic venesections in a patient with newly diagnosed hereditary hemochromatosis. Kardiol. Pol. 2020, 78, 786–787.

- Pietrangelo, A. Hereditary hemochromatosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 393–408.

- Barton, J.C.; Bertoli, L.F.; Rothenberg, B.E. Peripheral blood erythrocyte parameters in hemochromatosis: Evidence for increased erythrocyte hemoglobin content. J. Lab. Clin Med. 2000, 135, 96–104.

- Pietrangelo, A. Hereditary hemochromatosis—A new look at an old disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2383–2397.

- Casanova-Esteban, P.; Guiral, N.; Andrés, E.; Gonzalvo, C.; Mateo-Gallego, R.; Giraldo, P.; Paramo, J.A.; Civeira, F. Effect of phlebotomy on lipid metabolism in subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis. Metabolism 2011, 60, 830–834.

- Oh, R.C.; Hustead, T.R. Causes and evaluation of mildly elevated liver transaminase levels. Am. Fam. Physician 2011, 84, 1003–1008.

- Barton, J.C.; Acton, R.T. Diabetes in HFEHemochromatosis. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 9826930.

- Martinez, J.A.; Guerra, C.C.; Nery, L.E.; Jardim, J.R. Iron stores and coagulation parameters in patients with hypoxemic polycythemia secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The effect of phlebotomies. Sao Paulo Med. J. 1997, 115, 1395–1402.

- Newsome, P.N.; Cramb, R.; Davison, S.M.; Dillon, J.F.; Foulerton, M.; Godfrey, E.M.; Hall, R.; Harrower, U.; Hudson, M.; Langford, A.; et al. Guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests. Gut 2018, 67, 6–19.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 370–398.

- Moore, C., Jr.; Ormseth, M.; Fuchs, H. Causes and significance of markedly elevated serum ferritin levels in an academic medical center. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 19, 324–328.

- Carubbi, F.; Salvati, L.; Alunno, A.; Maggi, F.; Borghi, E.; Mariani, R.; Mai, F.; Paoloni, M.; Ferri, C.; Desideri, G.; et al. Ferritin is associated with the severity of lung involvement but not with worse prognosis in patients with COVID-19: Data from two Italian, COVID-19 units. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4863.

- Jacobs, E.M.; Hendriks, J.C.; van Tits, B.L.; Evans, P.J.; Breuer, W.; Liu, D.Y.; Jansen, E.H.; Jauhiainen, K.; Sturm, B.; Porter, J.B.; et al. Results of an international round robin for the quantification of serum non-transferrin-bound iron: Need for defining standardization and a clinically relevant isoform. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 341, 241–250.

- Shizukuda, Y.; Tripodi, D.J.; Rosing, D.R. Iron overload or oxidative stress? Insight into a mechanism of early cardiac manifestations of asymptomatic hereditary hemochromatosis subjects with C282Y homozygosity. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2016, 9, 400–401.

- Shizukuda, Y.; Bolan, C.D.; Tripodi, D.J.; Yau, Y.Y.; Nguyen, T.T.; Botello, G.; Sachdev, V.; Sidenko, S.; Ernst, I.; Waclawiw, M.A.; et al. Significance of left atrial contractile function in asymptomatic subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006, 98, 954–959.

- Rozwadowska, K.; Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L.; Fijałkowski, M.; Sikorska, K.; Szymanowicz, W.; Lewicka, E.; Raczak, G. Does the age of patients with hereditary hemochromatosis at the moment of their first diagnosis have an additional effect on the standard echocardiographic parameters? Eur. J. Transl. Clin. Med. 2018, 1, 20–25.

- Davidsen, E.S.; Hervig, T.; Omvik, P.; Gerdts, E. Left ventricular long-axis function in treated haemochromatosis. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2009, 25, 237–247.

- Leitman, M.; Lysiansky, M.; Lysyansky, P.; Friedman, Z.; Tyomkin, V.; Fuchs, T.; Adam, D.; Krakover, R.; Vered, Z. Circumferential and longitudinal strain in 3 myocardial layers in normal subjects and in patients with regional left ventricular dysfunction. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 64–70.

- Belghitia, H.; Brette, S.; Lafitte, S.; Reant, P.; Picard, F.; Serri, K.; Lafitte, M.; Courregelongue, M.; Dos Santos, P.; Douard, H. Automated function imaging: A new operator-independent strain method for assessing left ventricular function. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008, 101, 163–169.

- Geyer, H.; Caracciolo, G.; Abe, H.; Wilansky, S.; Carerj, S.; Gentile, F.; Nesser, H.J.; Khandheria, B.; Narula, J.; Sengupta, P.P.; et al. Assessment of myocardial mechanics using speckle tracking echocardiography: Fundamentals and clinical applications. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 351–455.

- Taber, L.A.; Yang, M.; Podszus, W.W. Mechanics of ventricular torsion. J. Biomech. 1996, 29, 745–752.

- Rüssel, I.K.; Götte, M.J.; Bronzwaer, J.G.; Knaapen, P.; Paulus, W.J.; van Rossum, A.C. Left ventricular torsion: An expanding role in the analysis of myocardial dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2009, 2, 648–655.

- Sun, J.P.; Lee, A.P.; Wu, C.; Lam, Y.Y.; Hung, M.J.; Chen, L.; Hu, Z.; Fang, F.; Yang, X.S.; Merlino, J.D. Quantification of left ventricular regional myocardial function using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in healthy volunteers—A multi-center study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 495–501.

- Takahashi, K.; Al Naami, G.; Thompson, R.; Inage, A.; Mackie, A.S.; Smallhorn, J.F. Normal rotational, torsion and untwisting data in children, adolescents and young adults. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 286–293.

- Burns, A.T.; la Gerche, A.; Prior, D.L.; Macisaac, A.I. Left ventricular untwisting is an important determinant of early diastolic function. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2009, 2, 709–716.

- Monte, I.; Buccheri, S.; Bottari, V.; Blundo, A.; Licciardi, S.; Romeo, M.A. Left ventricular rotational dynamics in Beta thalassemia major: A speckle-tracking echocardiographic study. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2012, 25, 1083–1090.

- Cheung, Y.F.; Liang, X.C.; Chan, G.C.; Wong, S.J.; Ha, S.Y. Myocardial deformation in patients with Beta-thalassemia major: A speckle tracking echocardiographic study. Echocardiography 2010, 27, 253–259.

- Di Odoardo, L.A.F.; Giuditta, M.; Cassinerio, E.; Roghi, A.; Pedrotti, P.; Vicenzi, M.; Sciumbata, V.M.; Cappellini, M.D.; Pierini, A. Myocardial deformation in iron overload cardiomyopathy: Speckle tracking imaging in a beta-thalassemia major population. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2017, 12, 799–809.

- Anderson, L.J. Assessment of iron overload with T2* magnetic resonance imaging. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 54, 287–294.

- Rozwadowska, K.; Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L.; Fijałkowski, M. Can two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography be useful for left ventricular assessment in the early stages of hereditary haemochromatosis? Echocardiography 2018, 35, 1772–1781.

- Byrne, D.; Walsh, J.P.; Daly, C.; McKiernan, S.; Norris, S.; Murphy, R.T.; King, G. Improvements in cardiac function detected using echocardiography in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 189, 109–117.

- Rozwadowska, K.; Raczak, G.; Sikorska, K.; Fijałkowski, M.; Kozłowski, D.; Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L. Influence of hereditary haemochromatosis on left ventricular wall thickness: Does iron overload exacerbate cardiac hypertrophy? Folia Morphol. 2019, 78, 746–753.

- Garceau, P.; Nguyen, E.T.; Carasso, S.; Ross, H.; Pendergrast, J.; Moravsky, G.; Bruchal-Garbicz, B.; Rakowski, H. Quantification of myocardial iron deposition by two-dimensional speckle tracking in patients with β-thalassaemia major and Blackfan-Diamond anaemia. Heart 2011, 97, 388–393.

- Ari, M.E.; Ekici, F.; Çetin, İ.İ.; Tavil, E.B.; Yaralı, N.; Işık, P.; Tunç, B. Assessment of left ventricular functions and myocardial iron load with tissue Doppler and speckle tracking echocardiography and T2* MRI in patients with β-thalassemia major. Echocardiography 2017, 34, 383–389.

- Wu, V.C.; Takeuchi, M. Three-dimensional echocardiography: Current status and real-life applications. Acta Cardiol. Sin. 2017, 33, 107–118.

- Aggeli, C.; Felekos, I.; Poulidakis, E.; Aggelis, A.; Tousoulis, D.; Stefanadis, C. Quantitative analysis of left atrial function in asymptomatic patients with b-thalassemia major using real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound. 2011, 9, 38.

- Schiau, C.; Schiau, Ş.; Dudea, S.M.; Manole, S. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance: Contribution to the exploration of cardiomyopathies. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2019, 92, 326–336.

- Barrera Portillo, M.C.; Uranga Uranga, M.; Sánchez González, J. Medición del T2* hepático y cardíaco en la hemocromatosis secundaria [Liver and heart T2* measurement in secondary haemochromatosis]. Radiologia 2013, 55, 331–339.

- Barrera Portillo, M.C.; Uranga Uranga, M.; Sánchez González, J.; Alústiza Echeverría, J.M.; Gervás Wells, C.; Guisasola Íñiguez, A. Multislice multiecho T2* cardiovascular magnetic resonance for detection of the heterogeneous distribution of myocardial iron overload. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2006, 23, 662–668.

- Jensen, P.D. Evaluation of iron overload. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 124, 697–711.

- Carpenter, J.P.; Grasso, A.E.; Porter, J.B.; Shah, F.; Dooley, J.; Pennell, D.J. On myocardial siderosis and left ventricular dysfunction in hemochromatosis. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2013, 15, 24.

- Furth, P.A.; Futterweit, W.; Gorlin, R. Refractory biventricular heart failure in secondary hemochromatosis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1985, 290, 209–213.

- Shizukuda, Y.; Tripodi, D.J.; Zalos, G.; Bolan, C.D.; Yau, Y.Y.; Leitman, S.F.; Waclawiw, M.A.; Rosing, D.R. Incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in asymptomatic hereditary hemochromatosis subjects with C282Y homozygosity. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 109, 856–860.

- Adams, P.; Altes, A.; Brissot, P.; Butzeck, B.; Cabantchik, I.; Cançado, R.; Distante, S.; Evans, P.; Evans, R.; Ganz, T.; et al. Therapeutic recommendations in HFE hemochromatosis for p.Cys282Tyr (C282Y/C282Y) homozygous genotype. Hepatol. Int. 2018, 12, 83–86.

- Saliba, A.N.; Harb, A.R.; Taher, A.T. Iron chelation therapy in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients: Current strategies and future directions. J. Blood Med. 2015, 6, 197–209.

- Kontoghiorghes, G.J. Comparative efficacy and toxicity of desferrioxamine, deferiprone and other iron and aluminium chelating drugs. Toxicol. Lett. 1995, 80, 1–18.

- Flaten, T.P.; Aaseth, J.; Andersen, O.; Kontoghiorghes, G.J. Iron mobilization using chelation and phlebotomy. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2012, 26, 127–130.

- Rombout-Sestrienkova, E.; De Jonge, N.; Martinakova, K.; Klöpping, C.; van Galen, K.P.; Vink, A.; Wajon, E.M.; Smit, W.M.; van Bree, C.; Koek, G.H.; et al. End-stage cardiomyopathy because of hereditary hemochromatosis successfully treated with erythrocytapheresis in combination with left ventricular assist device support. Circ. Heart Fail. 2014, 7, 541–543.

- Pennell, D.J.; Porter, J.B.; Piga, A.; Lai, Y.; El-Beshlawy, A.; Belhoul, K.M.; Elalfy, M.; Yesilipek, A.; Kilinç, Y.; Lawniczek, T.; et al. Cardiovascular T2-star (T2*) magnetic resonance for the early diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. Eur. Heart J. 2001, 22, 2171–2179.

- Anderson, L.J.; Holden, S.; Davis, B.; Prescott, E.; Charrier, C.C.; Bunce, N.H.; Firmin, D.N.; Wonke, B.; Porter, J.; Walker, J.M.; et al. Effect of deferiprone or deferoxamine on right ventricular function in thalassemia major patients with myocardial iron overload. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2011, 13, 34.

- Smith, G.C.; Alpendurada, F.; Carpenter, J.P.; Alam, M.H.; Berdoukas, V.; Karagiorga, M.; Ladis, V.; Piga, A.; Aessopos, A.; Gotsis, E.D.; et al. A 1-year randomized controlled trial of deferasirox vs deferoxamine for myocardial iron removal in β-thalassemia major (CORDELIA). Blood 2014, 123, 1447–1454.

- Tanner, M.A.; Galanello, R.; Dessi, C.; Westwood, M.A.; Smith, G.C.; Nair, S.V.; Anderson, L.J.; Walker, J.M.; Pennell, D.J. Myocardial iron loading in patients with thalassemia major on deferoxamine chelation. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2006, 8, 543–547.