Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | César Leyva-Porras | + 2375 word(s) | 2375 | 2021-07-28 11:22:37 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 2375 | 2021-08-18 02:25:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Leyva-Porras, C. Antioxidants: Improving Food Shelf Life. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/13280 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Leyva-Porras C. Antioxidants: Improving Food Shelf Life. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/13280. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Leyva-Porras, César. "Antioxidants: Improving Food Shelf Life" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/13280 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Leyva-Porras, C. (2021, August 17). Antioxidants: Improving Food Shelf Life. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/13280

Leyva-Porras, César. "Antioxidants: Improving Food Shelf Life." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 August, 2021.

Copy Citation

Oxidation is the main problem in preserving food products during storage. A relatively novel strategy is the use of antioxidant-enriched edible films. Antioxidants hinder reactive oxygen species, which mainly affect fats and proteins in food.

polysaccharides

antioxidants

loaded liposomes

edible films

food conservation

1. Introduction

Nowadays, one of the biggest challenges faced in the food industry is the rapid spoilage of foods [1]. Evidently, this problem results in a huge loss of money and large amounts of food in the world. Spoilage may be caused by three mechanisms named as the growth of microorganisms, oxidation, and enzymatic self-decomposition. The first mechanisms refers to the naturally occurring or externally added microorganisms, their growth and proliferation within the food [2]. Oxidation is the result of the action of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as oxygen-containing free radicals (–O), hydroxyl radicals (–OH), and superoxide anions (–O2) that may react with lipids and proteins, leading to an oxidative state [2][3][4]. Enzymatic decomposition is caused by the enzymes present in plant or animal cells that break down the fats and proteins of the food. An alternative to counter these mechanisms is the addition of substances that may inhibit the oxidative spoilage before vital molecules may be damaged. These substances are known as antioxidants, and are capable of hindering the effects of the ROS, either avoiding the chain chemical reactions or neutralizing the ROS [5]. There are natural and synthetic antioxidants, but the latter have been related to possible harm to human health [6][7]. Naturally occurring antioxidants are classified according to the chemical structure in carotenoids, vitamins, polyphenols, quinones, and minerals. Unfortunately, exposure to atmospheric air causes natural antioxidants to break down quickly, losing their properties and limiting their antioxidant activity [8][9][10][11]. One strategy to prolong their effect is through microencapsulation with carrying agents. These agents are based on carbohydrate polymers, which in turn are made up of polysaccharide chains such as glucose and fructose [12][13][14].

Several authors have discussed different methodologies for obtaining edible films such as wet (casting) and dry (extrusion) processes, and classified the films into edible coatings (applied directly to the food product), and preformed films (which wrap the product) [15][16]. They addressed the challenges faced by food manufacturers in relation to the loss of quality during storage, the subsequent deterioration, and the increase in waste. Although the packaging is an alternative to protect the quality of food, improve its shelf life, delaying microbial deterioration and providing barrier properties against moisture and gases, typical polymers used for this purpose may represent a risk for human health, as migration of molecules such as additives into the food from the polymeric matrix may occur. Another disadvantage is the environmental mark left by the plastic coating once it is disposed as solid waste. In consequence, this methodology is not environmentally friendly. Due to the above, several efforts have been made in order to substitute the traditional polymer packing by more environmental friendly materials such as biopolymers [17][18][19]. In this sense, a potential alternative to solve this problem with a low impact on the environment is the use of edible films made from natural polymers such as polysaccharides, proteins and fats [20][21][22][23][24][25].

2. Food Oxidation Processes

As mentioned, food can deteriorate due to several factors such as oxidation, which may be caused by the effects of UV light, ambient or cooking temperature and agrochemical residues. Proteins, lipids and sugars contained in food can suffer deterioration due to oxidation. Apart from the effect on the appearance and the loss of nutritional value, foods that have undergone oxidative processes can be harmful to health [12][26]. One of the main problems of the deterioration of beef, fish, and their derivatives, is the oxidation of lipids and proteins, which is produced by the uncontrolled generation of free radicals and reactive species [27]. These changes cause a deterioration in quality in terms of taste, color, texture and nutritional value. Additionally, it is very important to know the oxidation mechanism of fats and proteins, and their relationship with the majority component of foods, for example, proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates, in order to predict the oxidation rate and shelf life of the product.

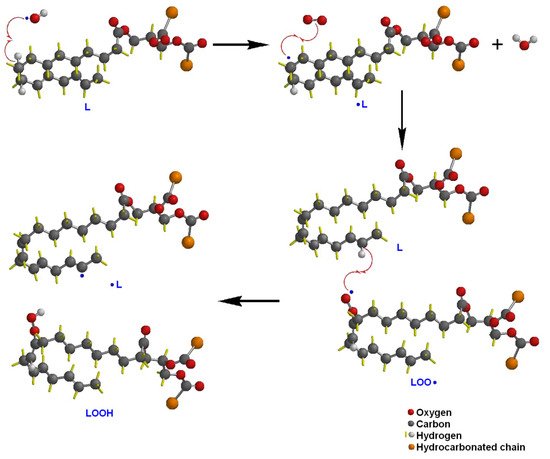

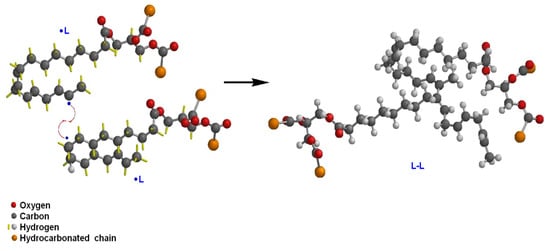

For lipids or fats, Jackson, et al. [28] conducted a study on the effect of oxidized lipids on health, specifically to set a relationship between the intake of oxidized lipids and the risk of developing chronic diseases. They suggested that the processes that include antioxidants to preserve food must be studied to confirm that they promote health and reduce the risk of developing diseases. Maldonado-Pereira et al. [29] studied the oxidation of cholesterol and its effect on food toxicity. They reported that there is abundant scientific evidence regarding the correlation between the consumption of cholesterol oxidation products and the risk of developing cancer and degenerative neurological diseases. Kato, et al. [30] published a methodology based on chromatography and mass spectroscopy in the quantification of the degree of oxidation in lipids, with greater sensitivity than that measured with the traditional method of the peroxide value (POV). They found that the phootoxidation of lipids produces peroxides on unsaturated carbons different from those obtained by thermo-oxidation. Waraho et al. [31] studied the reaction mechanisms in the oxidation of lipids in emulsion foods, such as dairy products. They found that some sugars such as hexose and pentose might act as pro-oxidants of lipids in emulsions. Additionally, because of the different characteristics of surfactants and emulsifiers, they suggested the use of antioxidants to reduce the possible oxidation and rancidity of emulsified products. Figure 1 and Figure 2 describe the oxidation reaction mechanism by hydroxyl radicals of an unsaturated lipid (L). The hydroxyl radical causes the homolytic cleavage of the hydrogen bond of the sp2 carbon, giving rise to a lipid radical •L. The lipid radical reacts with an O2 molecule to form a lipid-peroxide radical (LOO•). This reactive species can propagate lipid oxidation by taking hydrogen from another molecule and forming the lipid-hydroperoxide species (LOOH) and a new lipid radical susceptible to oxidation. It can also happen that two lipid radicals react with each other, leading to lipid crosslinking (Figure 2) [32].

Figure 1. Oxidation reaction mechanism by hydroxyl radicals of an unsaturated lipid (L).

Figure 2. Lipid crosslinking mechanism from the reaction of two lipid radicals.

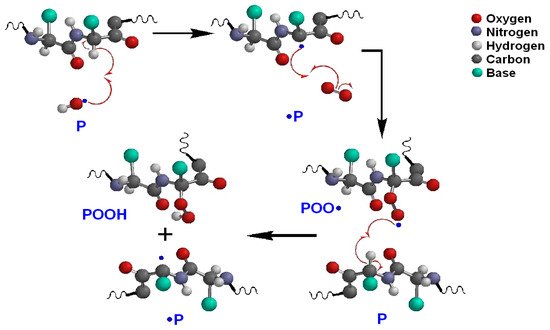

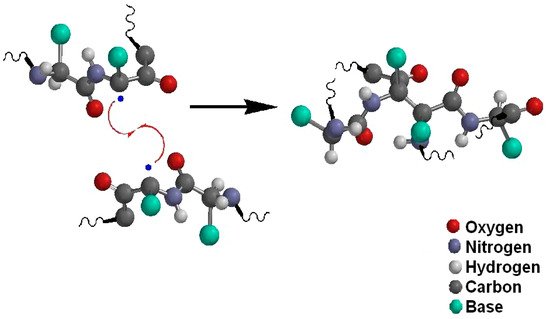

For proteins, Estévez and Luna [33] studied the effects on health due to the oxidation of proteins in food. They mentioned that some proteins or oxidized amino acids consumed in food can induce cellular malfunction, both due to a deterioration in self-regulation of the organism (homeostasis) and programmed cell death (apoptosis). Hellwig [34] carried out an extensive review on the oxidation mechanisms of proteins in food. Among the main sources of oxidizing species, he included ultraviolet light and transition metals such as iron. In addition, some polyphenols that inhibit lipid oxidation can act as pro-oxidants in proteins, but that this effect can be controlled with low concentrations of antioxidants. The oxidation mechanism in proteins is described in Figure 3. A reactive oxygen species can react with an amino acid chain (P) by reacting with hydrogen from one of the carbons, thus forming a free radical in the chain (•P). This radical reacts with an oxygen molecule forming a protein-peroxide radical (POO•) which in turn can react with hydrogen from another chain of amino acids creating a hydroperoxide (POOH) and a new free radical. The reaction between two protein radicals leads to the cross-linking of amino acid chains as shown in Figure 4 [35].

Figure 3. Oxidation mechanism in proteins.

Figure 4. The cross-linking of amino acid chains by the reaction of two protein radicals.

3. Naturally Occurring Antioxidants

In general, antioxidants refer to a wide range of substances that can be divided into endogenous or exogenous. Oroian and Escriche [36] classified the antioxidants mainly in vitamins (vitamins C and E), carotenoids (carotenes and xanthophylls), and polyphenols (flavonoids, phenolic acids, lignans and stilbenes). On the other hand, Carocho et al. [5] categorized the antioxidants by the most important groups, taking into account their properties, function and applicability in the industry, emphasizing polyphenols and the different groups of carotenoids, within natural antioxidants. Another way to catalog antioxidants is in terms of their solubility, which can be soluble in lipids/fats (hydrophobic) and water (hydrophilic). Both are necessary to protect cells, since the interior of cells and the fluid between is composed of water, while cell membranes are mostly made up of lipids. Because free radicals can attack any part of the cell, both types of antioxidants are needed to ensure the complete protection against oxidative damage [37]. A more precise definition of antioxidants is referring to the substances with the ability to hinder ROS or nitrogen species (RNS), in order to inhibit or stop the propagation of oxidative chain reactions before vital molecules may be damaged [5].

Plenty of the research regarding antioxidants of natural origin is focused on the relationship between human health and the intake of foods containing antioxidants [32][38][39]. Others are related to the extraction of bioactive molecules and their incorporation into food supplements or drugs in order to act in the body more efficiently [36][40]. Antioxidants can also be classified based on the reaction mechanism [41]. For example, antioxidants can neutralize the action of reactive species in cell membranes, through three mechanisms names ad (i) hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), (ii) single electron transfer (SET), and (iii) the ability to chelate metals from transition metal. In this sense, HAT mechanism is based on the ability of an antioxidant (HA) to hinder free radicals such as the peroxyl radical –ROO, by donating a hydrogen atom, stabilizing the peroxyl radical by resonance, according to the Equation (1) [42]:

While the SET mechanism is based on the ability of an antioxidant (HA) to transfer an electron to decrease free radicals, pro-oxidant metals such as Fe2+ and Cu2+, and carbonyls (Equations (2)–(4)). This mechanism depends on the solvent and pH:

Carotenoids are antioxidants found in foods such as carrots, pomegranates, and grapefruit, while tocopherols are present in oilseeds and green leafy vegetables, and ascorbic acid is found in citrus fruits [43]. Another example of phytochemical antioxidants is flavonoids, which have one of the most diverse groups of compounds present in food. According to the chemical structure, they are divided into six classes which are: flavanols, flavonones, flavones, flavonols, isoflavonoids and anthocyanidins. Because they can cross the blood-brain barrier and reduce oxidative stress in that area, their beneficial health effects include the anti-inflammatory effect, and the prevention and delay of the progression of chronic neurodegenerative diseases [44].

Regarding food preservation, the most studied antioxidants of natural origin are vitamins (tocopherols and ascorbic acid), stilbenes (resveratrol), and polyphenols (gallic acid and quercetin), as well as plant extracts (spices, leaves and fruits) that are a mixture of antioxidant molecules from various families, mainly polyphenols. Table 1 describes the type of antioxidant, description and natural source, applied research in the preservation of food and reference.

Table 1. Summary of the major findings of the applied research in the use of antioxidants for the preservation of foods.

| Ref. | Major Findings | Description | Antioxidant |

|---|---|---|---|

| [45] | Aa comparative study between different tocopherols and tocotrienols for the inhibition of the oxidation of vegetable oils and animal fats was carried out. It was found that at low concentrations, α-tocopherol is more efficient in scavenging free radicals, while γ-tocopherol was better at relatively high concentrations. | Tocopherols and tocotrienols | Vitamins |

| [46] | α-Tocopherol presented a better antioxidant performance in lipids when it is in the presence of phospholipids such as phosphatidylethanolamine. | ||

| [47] | The synergistic effect between propylgalate and α-tocopherol was compared. The authors found that the antioxidant properties in oil-in-water emulsions were greater than when only the tocopherol was used. This effect was attributed to a regeneration of the vitamin by the action of propylgalate. | ||

| [5] | Ascorbic acid not only allows one to maintain the quality of post-harvest vegetables, but also increases their shelf life and improves the properties of vegetables. | Vitamin C or ascorbic acid | |

| [48] | The effect of pre-harvest treatment with ascorbic acid and calcium lactate on bell pepper was studied. They found that the appearance and shelf life of the fruit increased with the treatment, also the amount of flavonoids in the fruit, thereby improving its antioxidant capacity. | ||

| [49] | A decrease in post-harvest enzymatic browning of mango beans of up to 50% when using an ascorbic acid treatment against a control without treatment was reported. They also noted that bean sprouts increased the polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity. | ||

| [50] | The antioxidant properties of resveratrol from the point of view of its chemical structure were studied. It was found that resveratrol inhibited lipid peroxidation by 89% compared to BHT and propylgalate, which had values of 68 and 83%, respectively. | Resveratrol | Stilbenes |

| [51] | Several resveratrol esters with long chain (C14, C16 and C18) and short chain (C3, C4, and C6) fatty acids were prepared and their antioxidant properties with different free radicals compared. It was that the antioxidant properties of long-chain resveratrol esters was better for the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazil (DPPH) radical. On the other hand, short chain esters showed a better antioxidant properties against 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS). | ||

| [5] | Recently this antioxidant has received special attention for food preservation, because it imparts an astringent flavor. It is used mainly in acidic juice drinks such as blueberry, and grape juices. Gallic acid esters, such as propylgalate, are used to prevent lipid oxidation. | Gallic acid | Polyphenols |

| [52] | The performance of the synthetic antioxidant tertbutylhydroquinone (TBHQ) was evaluated against gallic acid, and a mixture of methyl gallate with gallic acid, in the thermal oxidation of lipids. During the thermal oxidation, so-called second-stage oxidized species are generated, that is, oxidized products of lipid peroxides. It ws found that at low temperatures TBHQ performs better, but at 120 °C, the gallic acid, and its mixture with methyl gallate, showed a better performance. | ||

| [53] | The antioxidant effect of quercetin, epicatechin and naringenin on methyl linoleate was studied. They found that naringenin had a poor antioxidant effect compared to quercetin and epicatechin. | Quercetin | |

| [54] | The antioxidant properties of quercetin and quercetin with α-tocopherol in chicken meat were studied. Greater preservation of the meat was observed under storage conditions when quercetin was used, in addition to the elimination of odors caused by carbonyl compounds. However, the appearance of a yellow color can be avoided if tocopherol is also used in addition to the quercetin. | ||

| [55] | The oxidation of lipids and proteins in chicken pate was evaluated in the presence of quercetin and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). Quercetin was found to be eight times more efficient in inhibiting lipid oxidative reactions than BHT. However, quercetin was not as efficient in inhibiting protein oxidation. |

References

- Eça, K.S.; Sartori, T.; Menegalli, F.C. Films and edible coatings containing antioxidants-a review. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2014, 17, 98–112.

- Sánchez-Ortega, I.; García-Almendárez, B.E.; Santos-López, E.M.; Amaro-Reyes, A.; Barboza-Corona, J.E.; Regalado, C. Antimi-crobial edible films and coatings for meat and meat products preservation. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 248935.

- Ayala, F.; Echávarri, J.F.; Olarte, C.; Sanz, S. Quality characteristics of minimally processed leek packaged using different films and stored in lighting conditions. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 1333–1343.

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Pateiro, M.; Fontán, M.C.G.; Carballo, J. Effect of fat content on physical, microbial, lipid and protein changes during chill storage of foal liver pâté. Food Chem. 2014, 155, 57–63.

- Carocho, M.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C. Antioxidants: Reviewing the chemistry, food applications, legislation and role as pre-servatives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 71, 107–120.

- Takahashi, O. Haemorrhages due to defective blood coagulation do not occur in mice and guinea-pigs fed butylated hydroxy-toluene, but nephrotoxicity is found in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1992, 30, 89–97.

- Wang, W.; Kannan, P.; Xue, J.; Kannan, K. Synthetic phenolic antioxidants, including butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), in resin-based dental sealants. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 339–343.

- Ceci, C.; Graziani, G.; Faraoni, I.; Cacciotti, I. Strategies to improve ellagic acid bioavailability: From natural or semisynthetic derivatives to nanotechnological approaches based on innovative carriers. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 382001.

- Ghosh, A.; Ghosh, D.; Sarkar, S.; Mandal, A.K.; Choudhury, S.T.; Das, N. Anticarcinogenic activity of nanoencapsulated quercetin in combating diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinoma in rats. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 21, 32–41.

- Maqsoudlou, A.; Assadpour, E.; Mohebodini, H.; Jafari, S.M. Improving the efficiency of natural antioxidant compounds via different nanocarriers. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 278, 102122.

- Xiong, Y.; Li, S.; Warner, R.D.; Fang, Z. Effect of oregano essential oil and resveratrol nanoemulsion loaded pectin edible coating on the preservation of pork loin in modified atmosphere packaging. Food Control. 2020, 114, 107226.

- Aguiar, J.; Costa, R.; Rocha, F.; Estevinho, B.; Santos, L. Design of microparticles containing natural antioxidants: Preparation, characterization and controlled release studies. Powder Technol. 2017, 313, 287–292.

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Ma, J.; Kang, M.; Ding, C.; Ming, D. Preparation of β-CD-Ellagic Acid Microspheres and Their Effects on HepG2 Cell Proliferation. Molecules 2017, 22, 2175.

- Tapia-Hernández, J.A.; Rodríguez-Felix, F.; Juárez-Onofre, J.E.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Robles-García, M.A.; Borboa-Flores, J.; Wong-Corral, F.J.; Cinco-Moroyoqui, F.J.; Castro-Enríquez, D.D.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L. Zein-polysaccharide nanoparticles as matrices for antioxidant compounds: A strategy for prevention of chronic degenerative diseases. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 451–471.

- Suhag, R.; Kumar, N.; Petkoska, A.T.; Upadhyay, A. Film formation and deposition methods of edible coating on food products: A review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109582.

- Jiang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Rui, X.; Aisa, H.A. A comprehensive review on the research progress of vegetable edible films. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103049.

- Palkopoulou, S.; Joly, C.; Feigenbaum, A.; Papaspyrides, C.D.; Dole, P. Critical review on challenge tests to demonstrate de-contamination of polyolefins intended for food contact applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 49, 110–120.

- Geueke, B.; Groh, K.; Muncke, J. Food packaging in the circular economy: Overview of chemical safety aspects for commonly used materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 491–505.

- Walker, T.R.; McGuinty, E.; Charlebois, S.; Music, J. Single-use plastic packaging in the Canadian food industry: Consumer behavior and perceptions. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 1–11.

- Chaple, S.; Vishwasrao, C.; Ananthanarayan, L. Edible Composite Coating of Methyl Cellulose for Post-Harvest Extension of Shelf-Life of Finger Hot Indian Pepper (Pusa jwala). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2016, 41, e12807.

- Muller, J.; González-Martínez, C.; Chiralt, A. Combination of Poly(lactic) Acid and Starch for Biodegradable Food Packaging. Materials 2017, 10, 952.

- Thakur, R.; Pristijono, P.; Bowyer, M.; Singh, S.P.; Scarlett, C.J.; Stathopoulos, C.; Vuong, Q.V. A starch edible surface coating delays banana fruit ripening. LWT 2019, 100, 341–347.

- Nazrin, A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Zuhri, M.Y.M.; Ilyas, R.; Syafiq, R.; Sherwani, S.F.K. Nanocellulose Reinforced Thermoplastic Starch (TPS), Polylactic Acid (PLA), and Polybutylene Succinate (PBS) for Food Packaging Applications. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 213.

- Pinzon, M.I.; Sanchez, L.T.; Garcia, O.R.; Gutierrez, R.; Luna, J.C.; Villa, C.C. Increasing shelf life of strawberries (Fragaria ssp) by using a banana starch-chitosan-Aloe vera gel composite edible coating. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 55, 92–98.

- Zhao, X.; Cornish, K.; Vodovotz, Y. Narrowing the gap for bioplastic use in food packaging: An update. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 4712–4732.

- Estévez, M.; Li, Z.; Soladoye, P.O.; Van-Hecke, T. Health Risks of Food Oxidation. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 82, pp. 45–81.

- Umaraw, P.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Verma, A.K.; Barba, F.J.; Singh, V.; Kumar, P.; Lorenzo, J.M. Edible films/coating with tailored properties for active packaging of meat, fish and derived products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 98, 10–24.

- Jackson, V.; Penumetcha, M. Dietary oxidised lipids, health consequences and novel food technologies that thwart food lipid oxidation: An update. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1981–1988.

- Maldonado-Pereira, L.; Schweiss, M.; Barnaba, C.; Medina-Meza, I.G. The role of cholesterol oxidation products in food toxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 908–939.

- Kato, S.; Shimizu, N.; Hanzawa, Y.; Otoki, Y.; Ito, J.; Kimura, F.; Takekoshi, S.; Sakaino, M.; Sano, T.; Eitsuka, T. Determination of triacylglycerol oxidation mechanisms in canola oil using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. NPJ Sci. Food 2018, 2, 1–11.

- Waraho, T.; McClements, D.; Decker, E.A. Mechanisms of lipid oxidation in food dispersions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 3–13.

- Nimse, S.B.; Pal, D. Free radicals, natural antioxidants, and their reaction mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27986–28006.

- Estévez, M.; Luna, C. Dietary protein oxidation: A silent threat to human health? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3781–3793.

- Hellwig, M. The Chemistry of Protein Oxidation in Food. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16742–16763.

- Papuc, C.; Goran, G.V.; Predescu, C.N.; Nicorescu, V. Mechanisms of Oxidative Processes in Meat and Toxicity Induced by Postprandial Degradation Products: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 16, 96–123.

- Oroian, M.; Escriche, I. Antioxidants: Characterization, natural sources, extraction and analysis. Food Res. Int. 2015, 74, 10–36.

- Mercola, J. Fat for Fuel: A Revolutionary Diet to Combat Cancer, Boost Brain Power, and Increase Your Energy; Hay House: Carlsbad, CA, USA, 2017.

- Wootton-Beard, P.C.; Ryan, L. Improving public health? The role of antioxidant-rich fruit and vegetable beverages. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 3135–3148.

- Jiang, J.; Xiong, Y.L. Natural antioxidants as food and feed additives to promote health benefits and quality of meat products: A review. Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 107–117.

- Samoticha, J.; Jara-Palacios, M.J.; Hernández-Hierro, J.M.; Heredia, F.J.; Wojdyło, A. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant ac-tivity of twelve grape cultivars measured by chemical and electrochemical methods. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1933–1943.

- Brewer, M.S. Natural Antioxidants: Sources, Compounds, Mechanisms of Action, and Potential Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011, 10, 221–247.

- Apak, R.; Gorinstein, S.; Böhm, V.; Schaich, K.M.; Özyürek, M.; Güçlü, K. Methods of measurement and evaluation of natural antioxidant capacity/activity (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 957–998.

- Arulselvan, P.; Fard, M.T.; Tan, W.S.; Gothai, S.; Fakurazi, S.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Kumar, S.S. Role of Antioxidants and Natural Products in Inflammation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 5276130.

- Khan, H.; Ullah, H.; Aschner, M.; Cheang, W.S.; Akkol, E.K. Neuroprotective Effects of Quercetin in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2019, 10, 59.

- Seppanen, C.M.; Song, Q.; Csallany, A.S. The Antioxidant Functions of Tocopherol and Tocotrienol Homologues in Oils, Fats, and Food Systems. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 469–481.

- Xu, N.; Shanbhag, A.G.; Li, B.; Angkuratipakorn, T.; Decker, E.A. Impact of phospholipid–tocopherol combinations and en-zyme-modified lecithin on the oxidative stability of bulk oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 7954–7960.

- Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Nie, S.; Xie, M. Combined application of gallate ester and α-tocopherol in oil-in-water emulsion: Their distribution and antioxidant efficiency. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2019, 41, 909–917.

- Barzegar, T.; Fateh, M.; Razavi, F. Enhancement of postharvest sensory quality and antioxidant capacity of sweet pepper fruits by foliar applying calcium lactate and ascorbic acid. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 241, 293–303.

- Sikora, M.; Świeca, M. Effect of ascorbic acid postharvest treatment on enzymatic browning, phenolics and antioxidant capacity of stored mung bean sprouts. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 1160–1166.

- Gülçin, İ. Antioxidant properties of resveratrol: A structure–activity insight. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 210–218.

- Oh, W.Y.; Shahidi, F. Lipophilization of Resveratrol and Effects on Antioxidant Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8617–8625.

- Farhoosh, R.; Nyström, L. Antioxidant potency of gallic acid, methyl gallate and their combinations in sunflower oil triacyl-glycerols at high temperature. Food Chem. 2018, 244, 29–35.

- Palma, M.; Robert, P.; Holgado, F.; Márquez-Ruiz, G.; Velasco, J. Antioxidant Activity and Kinetics Studies of Quercetin, Epicatechin and Naringenin in Bulk Methyl Linoleate. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 1189–1196.

- Sohaib, M.; Anjum, F.M.; Arshad, M.S.; Imran, M.; Imran, A.; Hussain, S. Oxidative stability and lipid oxidation flavoring vol-atiles in antioxidants treated chicken meat patties during storage. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 1–10.

- de Carli, C.; Moraes-Lovison, M.; Pinho, S.C. Production, physicochemical stability of quercetin-loaded nanoemulsions and evaluation of antioxidant activity in spreadable chicken pâtés. LWT 2018, 98, 154–161.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology; Polymer Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Aug 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No