| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gengxi Lu | + 2961 word(s) | 2961 | 2021-08-13 05:29:33 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 2961 | 2021-08-16 03:57:47 | | |

Video Upload Options

Photoacoustic (PA) imaging is able to provide extremely high molecular contrast while maintaining the superior imaging depth of ultrasound (US) imaging. Conventional microscopic PA imaging has limited access to deeper tissue due to strong light scattering and attenuation. Endoscopic PA technology enables direct delivery of excitation light into the interior of a hollow organ or cavity of the body for functional and molecular PA imaging of target tissue.

1. Introduction

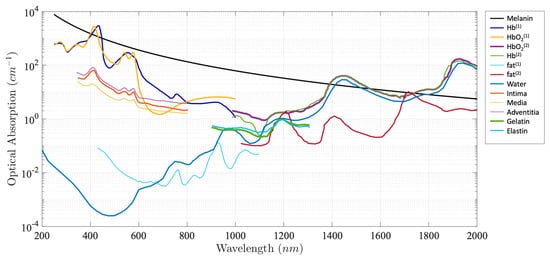

Photoacoustic (PA) imaging, an emerging biomedical imaging modality, has the advantage of providing optical absorption contrast with a greater penetration depth compared with conventional optical imaging modalities [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]. In PA imaging, the biological tissue is irradiated by a pulsed light. A portion of the optical energy is absorbed by tissue and converted into heat, resulting in a transient pressure rise. This initial pressure acts as an acoustic source that generates an acoustic wave propagating through the tissue. An ultrasonic transducer is often used for detecting the acoustic wave to form PA images. Due to the introduction of a US transducer, US imaging can be incorporated seamlessly. Alternatively, an all optical US sensor, such as a Fabry–Pérot interferometer and microresonator, can be also applied to detect a generated PA signal [10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17]. The intensity of the generated PA signal is proportional to the local absorption coefficient of the tissue, the light intensity, and the Grüneisen parameter, which represents thermoacoustic conversion efficiency. Different biological tissues exhibit different absorption spectra, as shown in Figure 1.

As an extension of PA imaging, spectroscopic PA imaging can be performed by applying multiwavelength laser excitation and a spectroscopic analysis for tissue characterization and quantification due to tissue unique spectral signatures. Spectroscopic PA imaging has been investigated in a wide variety of applications. For example, spectroscopic PA has been applied in intravascular imaging to detect and distinguish peri-adventitial and atherosclerotic lipids, one of the main characteristics of vulnerable plaque [4][22][23]. Another important application is to measure blood oxygen saturation (SO 2), which is a key factor for cancer detection and staging, using the differences in oxyhemoglobin (HbO 2) and deoxyhemoglobin (HHb) [24][25].

2. Endoscopic Photoacoustic Imaging System

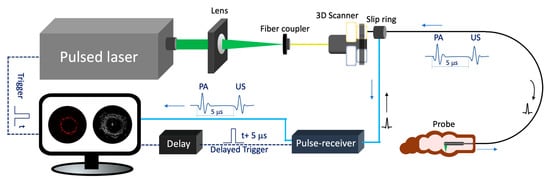

Figure 2 depicts the schematic of a representative endoscopic PA imaging system setup [26]. A nanosecond pulsed laser is used for PA signal excitation. The output laser beam is focused by a condenser lens into the imaging probe to excite the target tissue. A US transducer is used to detect the generated PA signal. Due to the introduction of a US transducer, US imaging can be performed simultaneously. To separate PA and US signals, a delay unit is often applied to delay US pulse emission by a few nanoseconds. For radial scanning, a scanner consisting of an optical rotary joint and slip ring can be utilized to pass optical and electrical signals across rotating interfaces. With this scanning mechanism, the imaging probe can be miniaturized in terms of outer diameter and rigid length. However, nonuniform rotation distortion (NURD) will be a main concern, especially for intravascular imaging. Alternatively, a micromotor can be incorporated into the imaging probe tip to rotate the mirror only, instead of the entire imaging probe. This scanning mechanism will enable uniform rotation at the cost of increased rigid length. Table 1 and Table 2 show representative endoscopic PA imaging systems and corresponding key parameters.

| Study | Laser | US Sensor | Coaxial | Dimension (mm) |

Frame Rate | PA Resolution |

Scanning Mechanism | Application | Functional Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al. [27] | Tunable dye laser 584 nm | F: 4 mm, ƒ0: 33 M Ring-shaped PMN-PT |

Y | OD: 2.5 mm RL: 35 mm |

4 Hz | L: 100 µm A: 58 µm |

Micromotor | In vivo rat colon | - |

| He et al. [28] | DPSS laser: 2 kHz, 532 nm |

Focus: 7 mm, ƒ0: 30 M Ring-shaped PVDF |

Y | OD: 18.6 mm RL: 20 mm |

2.5 Hz | L: 80 µm A: 55 |

Torque coil-based scanning | Ex vivo pig esophagus | - |

| Li et al. [29] | 8 kHz, 527 nm | Unfocused, ƒ0: 15 MHz | Y | OD: 8 mm Rigid |

2 Hz | L: 40 µm A: 125 |

Shaft based scanning |

In vivo rabbit rectum | - |

| Xiong et al. [30] | 10 kHz, 527 nm | Unfocused, ƒ0: 15 MHz | Y | OD: 9 mm Rigid |

- | L: 91 µm A: 121 |

Shaft | In vivo rabbit rectum | - |

| Jin et al. [31] | 100 kHz to 5 MHz, 1064 nm |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 6 MHz | N | OD: 1.2 mm | - | L: 37 µm A: 253 µm |

Shaft | In-situ esophageal tumor | viscoelasticity |

| Yang et al. [32] | Q-switched diode-pumped Nd:YAG laser, 8 kHz, 532 nm | F = 4.4 mm, ƒ0: 42 MHz, Ring-shaped LiNbO3 | Y | OD: 3.8 mm | 2 Hz | L: 10 µm A: 50 µm |

Micromotor | In vivo rat colorectum | - |

| Liu et al. [33] | Q-switched lasers, 10 kHz, 532 nm | F = 17 mm, ƒ0: 15 MHz, Ring-shaped PVDF | Y | OD: 12 mm Rigid |

5 Hz | L: 40 µm A: 60 µm |

Micromotor | In vivo rabbit rectum | - |

| Yang et al. [25] | Tunable dye laser 562 nm, 584 nm | F = 5.2 mm, ƒ0: 36 MHz, Ring-shaped LiNbO3 | Y | OD: 3.8 mm R: 38 mm |

4 Hz | L: 80 µm A: 55 µm |

SO2 level | In vivo rat colon | SO2 level |

| Basij et al. [34] | Nd:YAG/OPO laser 532 nm | 64-element phased-array, ƒ0: 5–10 MHz | N | OD: 7.5 mm | - | L: 378 µm A: 308 |

Phase array ultrasound | Phantom | - |

| Yuan et al. [35] | Nd:YAG laser, 20 Hz, 1064 nm | 64-element ring-shaped array, ƒ0: 6 MHz, | N | OD: 30 mm Rigid |

- | L: 2.4 mm A: 320 µm |

transducer array | Ex vivo pig Colorectal tissue | - |

| Guo et al. [36] | Nd:YAG laser, 20 kHz, 532 nm | Unfocused, ƒ0: 10 MHz | N | OD: 6 mm Rigid |

1/8 Hz | L: 10.6 µm A: 105 |

MEMS scanning | Ex vivo Mouse colon tissue | - |

| Ansari et al. [10] | Nd:YAG laser, 20 Hz, 1064 nm | Fabry-Pérot (FP) polymer-film | Y | OD: 3.2 mm | 25 mins/volume | L: 45 µm A: 31 µm |

galvanometer | In vivo mouse skin | - |

| Li et al. [37] | DPSS laser, Single Shot to 300 kHz 532 nm |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 45 MHz PMN-PT |

N | OD: 1.5 mm A: 11 mm |

50 Hz | L: 250 µm A: 50 µm |

Torque coil-based scanning | In vivo rat rectum | - |

Table 2. Representative intravascular photoacoustic imaging systems.

| Study | Laser | US Sensor | Coaxial | Dimension (mm) |

Frame Rate | PA Resolution |

Scanning Mechanism | Application | Functional Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ji et al. [38] | OPO laser, 10 Hz, 750 nm |

dual element unfocused transducer ƒ0: 19 MHz |

N | OD: 1.2 mm R: 20 mm |

- | L: 13 µm A: 127 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Ex vivo rabbit aorta | - |

| Li et al. [39] | Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, 10 Hz, 532 nm | Dual element unfocused transducer ƒ0: 35 and 80 MHz |

N | OD: 1.2 mm | - | L: 232/181 µm A: 59/35 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Ex vivo rabbit aorta | |

| Piao et al. [40] | OPO laser, 500 Hz, 1725 nm |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 45 MHz | N | OD: 1 mm R: 6 mm |

1 Hz | L: 350 µm A: 60 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Ex vivo rabbit aorta | |

| Jansen et al. [22] | OPO laser, 10 Hz, 1125:2:1275 |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 44.5 MHz, PMN-PT |

N | OD: 1 mm | - | - | Torque, coil based scanning | human atherosclerotic coronary artery, ex vivo | Spectroscopic imaging |

| Wang et al. [41] | OPO laser, 10 Hz, 1720 nm |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 40 MHz |

N | OD: 2.2 mm | - | - | Torque, coil based scanning | In vivo rabbit aorta with blood |

- |

| Mathews et al. [11] | Tunable dye laser, 565 to 605 nm |

Fabry–Pérot (FP) polymer film | N | OD: 1.25 mm | 1/15 Hz | L: 18 µm A: 45 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Phantom | - |

| Zhang et al. [42] | OPO laser, 10 Hz, 720, 760 nm |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 20 MHz |

N | OD: 1.8 mm | - | L: 380 µm A: 100 |

Torque, coil based scanning | In vivo rabbit aorta with blood |

Spectroscopic imaging |

| Wang et al. [43] | OPO laser, 10 Hz, 1700 nm |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 15 MHz |

N | OD: 1.1 mm | - | L: 94 µm A: 122 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Ex vivo rabbit aorta | Elasticity imaging |

| Wei et al. [8] |

Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, 10 Hz, 532 nm | Unfocused, ƒ0: 39 MHz Ring-shaped |

Y | OD: 2.3 mm | - | L: 230 µm A: 34 µm |

Rotating target | Ex vivo rabbit aorta | - |

| Xie et al. [44] | 8 kHz to 100 kHz, 1064 nm | Unfocused, ƒ0: 40 MHz PZT |

N | OD: 0.9 mm | 100 Hz | - | Torque, coil based scanning | In vivo rabbit aorta with nanoparticles | - |

| Hui et al. [45] | KTP-based OPO, 500 Hz, 1724 nm | F: 3 mm, ƒ0: 35 MHz Ring-shaped |

Y | OD: >2.5 mm | 1 Hz | L: 260 µm A: 102 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Ex vivo human femoral artery | - |

| Wu et al. [46] | Periodically-poled LiNbO3 OPO, 5 kHz 1720 nm | Unfocused, ƒ0: 40 MHz | N | OD: 1.3 mm with sheath | 20 Hz | - | Torque, coil based scanning | In vivo swine coronary lipid model | - |

| Lei et al. [47] | OPO laser, 2.5 kHz, 1720 nm |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 50 MHz | N | 0.7 mm | 5 Hz | L: 209 µm A: 61 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Ex vivo thoracic aorta mouse | - |

| Bai et al. [48] | OPO laser, 10 Hz, 1210 nm | Unfocused, ƒ0: 40 MHz PZT |

N | 1.1 mm | 1/160 Hz | L: 19.6 µm A: 38.1 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Ex vivo phantom | - |

| Li et al. [49] | OPO laser, 1 kHz 1210 nm, 1720 nm |

Unfocused, ƒ0: 40 MHz PZT |

N | 0.9 mm | 5 Hz | L: 200 µm A: 100 µm |

Torque, coil based scanning | Ex vivo phantom | Spectroscopic imaging |

A nanosecond laser is one of the key components of a PA imaging system as its repetition rate determines the maximum imaging speed and its energy affects the signal to noise ratio of the PA signal. In most reported studies, a Q-switched Nd: YAG pumped optical parametric oscillator (OPO), Ti: sapphire, or dye laser systems are used for PA signal excitation, in which a tunable wavelength enables spectroscopic PA imaging [11][25][27][32][38][42]. This OPO often operates at a slow repetition rate (~10 Hz) and slow tuning speed. In addition, diode pumped solid state (DPSS) lasers have been introduced into PA imaging due to their high power and repetition rate, so that a high frame rate can be achieved [37][28]. However, DPSS laser based PA systems are incapable of performing spectroscopic PA imaging due to their single wavelength operation.

3. Endoscopic Photoacoustic Imaging System Probe

In order to achieve high quality PA images, an optimal imaging probe that includes an optical fiber to deliver excitation light and a US detector for signal detection is essential. Various probes using different types of light delivery, US detection, and scanning mechanisms have been investigated. Each has its own advantages and limitations. Based on clinical applications, these designs can be categorized into two groups: GI tract and intravascular imaging probes.

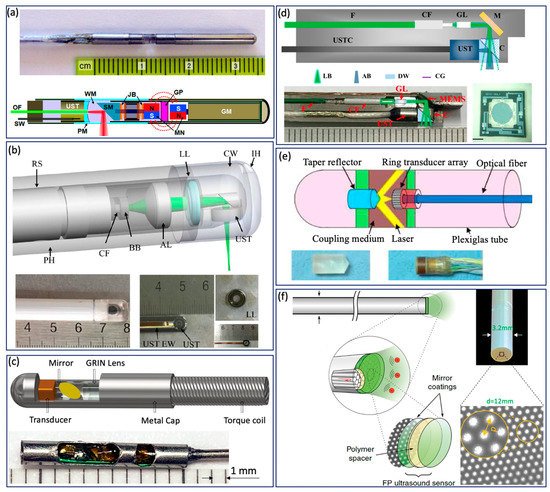

Various GI tract imaging probes have been proposed [3][10][15][37][26][25][27][29][30][32][34][35][36][50][51][52][53][54][55], as shown in Figure 3 . Yang et al. reported a series of micromotor based endoscopic PA probes [3][25][27][32][52]. The probe consists of a ring-shaped US transducer and an optical fiber which is mounted in the central opening of the ultrasonic transducer. A mirror aligned with the fiber tip and US transducer coaxially is driven by a micromotor to reflect both laser and acoustic beams towards the tissue, as shown in Figure 3 a. This imaging probe has a limited field of view due to being blocked by the stainless steel wall. In addition, the imaging speed is relatively slow, because the mirror is rotated through a magnetic coupling mechanism in order to isolate the micromotor from water. To address this issue, Xiong et al. [30] and Li et al. [29] reported several similar coaxial PA imaging probes with different scanning mechanisms, in which the entire imaging probe or probe shell was rotated by an external motor at a frequency of 2 Hz. In addition, the ring-shaped US transducer was aligned with the laser beam coaxially and placed near the imaging window, as shown in Figure 3 b. This configuration will avoid extra US signal attenuation caused by the reflection of the mirror, thereby improving sensitivity. To perform high speed and full field of view imaging, Li et al. [37][26] developed a PA probe with torque coil based scanning, in which optical and acoustic components are arranged in a series. Optical and/or acoustic beams are tilted to achieve an overlap between two beams for effective PA signal detection. The imaging speed is up to 50 Hz. The main limitations include limited imaging range and additional steps for achieving coregistered PA and US images due to longitudinal offset between the two beams. In addition to the radial scanning mechanism, Guo et al. [36] and Qu et al. [53] demonstrated a microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) scanning mirror based imaging probe, as shown in Figure 3 d, which is able to perform fast raster scanning. The maximum scanning frequency of this MEMS mirror is 500 Hz, which can support a 1000 Hz frame rate with the fast laser. The main limitation is its relatively large probe size due to the use of MEMS. To perform cross sectional imaging without scanning, Yuan et al. [35] developed an imaging probe ( Figure 3 c) based on a ring-shaped array US transducer, in which a transducer and optical fiber were aligned coaxially. A tapered reflector was used to transform the laser beam into a ring- shaped distribution to illuminate the sample and a 64-element ring transducer array connected with the parallel acquisition system was used to detect the generated PA signal, as shown in Figure 3 e. Basij et al. [34] present a phased array US transducer based imaging probe, in which six silica core/cladding optical fibers surrounding the US transducer were used to illuminate the sample. In addition to the traditional US transducer, an optical US sensor (such as a micro ring resonator and FP sensors) has been used in endoscopic PA imaging probes [10][15][54][55]. Figure 3 f shows a representative all optical imaging probe, which consists of a fiber bundle and the Fabry–Pérot (FP) US sensor at the fiber tip [10].

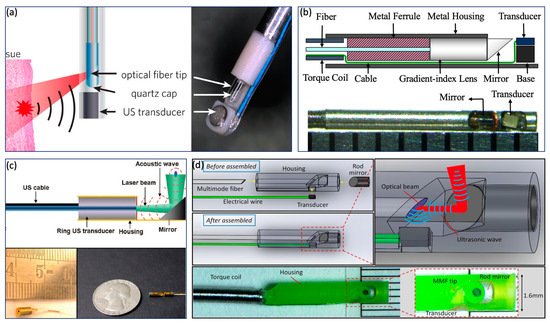

In contrast to the GI tract imaging probe, an intravascular imaging probe needs to be implemented with a smaller diameter and shorter rigid length in order to realize a smooth advance in the tortuous cardiovascular system. Various probe configurations were reported [8][49][56][40][46][57][58][59][60][61], as shown in Figure 4 . Wu et al. proposed a 0.8 mm noncoaxial probe, in which a multimode fiber end was angle polished to enable total reflection for laser delivery and a side-facing US transducer was aligned in a series for PA signal detection. The lateral resolution of this kind of probe is relatively poor due to the broad illumination [46]. With the same alignment, Li et al. [49] introduced a grin lens at the end of the optical fiber to achieve a quasifocusing illumination ( Figure 4 b). An improved resolution of ~200 µm was obtained. To further improve lateral resolution, Zhang et al. applied a graded index multimode fiber to replace a multimode fiber for light propagation, which enables a beam self-cleaning effect and offers a lateral resolution of 30 μm [57]. Wang et al. proposed to utilize a tapered fiber (core: from Ø25 to Ø9 μm) instead of a multimode fiber, which contributes to an optimal lateral resolution of 18 μm [58]. However, the above mentioned noncoaxial imaging probes [49][40][46][57][58][59] have limited imaging range and require additional steps to achieve coregistered PA and US images. To address these issues, Wei et al. [8] and Cao et al. [60] presented coaxial imaging probes, as shown in Figure 4 c,d, in which optical and acoustic beams share the same optical path. This configuration can be realized by using a ring-shaped US transducer ( Figure 4 c) or multireflection scheme ( Figure 4 d), which enables a long imaging range and automatic image coregistration [8][56][60]. The limitations of these designs include a relatively large size due to the use of the ring-shaped US transducer and degraded sensitivity caused by multiple reflections of the PA/US signal.

4. Application

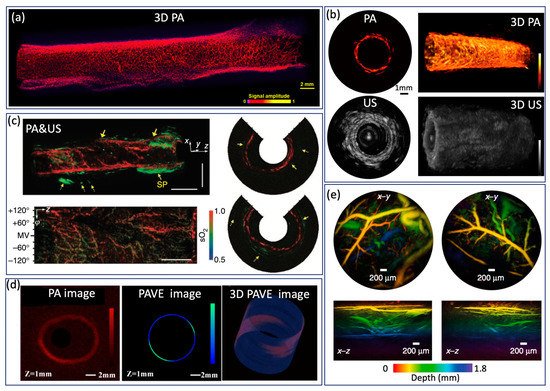

Endoscopic PA imaging provides molecular contrast with depth information, which allows for the simultaneous visualization of structural and functional information. It has attracted intensive research interest and been applied in GI tract for characterization of diseases in GI tract by mapping vasculature, measuring SO 2 saturation, and evaluating elasticity. Yang et al. [32] present a high-resolution endoscopic PA system, which enables visualization of vasculature with a much finer resolution of 10 µm and an imaging speed of 2 Hz, as shown in Figure 5a. However, imaging speed is main limitation for clinical application. To achieve real time imaging, Li et al. [37] developed a high speed PA imaging system, which is able to perform PA and US imaging simultaneously with an imaging speed up to 50 Hz. Nevertheless, the lateral resolution is about ~300 µm, which makes it difficult to identify microvascular systems clearly. To obtain functional information about the GI tract, Yang et al. [25] demonstrated a functional PA and US system by applying an excitation of multiple wavelengths, which allows the simultaneous visualization of vasculature, SO 2 level, and the morphology of a rat colon, as shown in Figure5c. This is the first demonstration of measuring SO 2 in the GI tract and represents a significant step toward comprehensive diagnosis, but the imaging speed is still a main concern for clinical translation of this technology. Jin et al. further extend PA imaging to perform elastography using phase sensitive PA imaging [31], in which tissue biomechanics and morphology can be obtained by detecting the PA phase and PA amplitude information, respectively. Ex vivo experiments were performed to demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed system, as shown in Figure 5d. The accuracy and speed of imaging still need to be further improved for in vivo application. To realize noncontact endoscopic imaging, Ansari et al. demonstrated an all optical endoscopic imaging probe with a Fabry–Pérot (FP) polymer-film as the US sensor [10], which can provide high resolution 3D vasculature of mouse abdominal skin. This approach avoids the need for separate and bulky detectors, providing more flexibility. However, the shallow penetration depth (~2 mm) and long acquisition time (25 min for two images) inhibit clinical application.

References

- Wang, X.; Pang, Y.; Ku, G.; Xie, X.; Stoica, G.; Wang, L. Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 803–806.

- Brecht, H.-P.F.; Su, R.; Fronheiser, M.P.; Ermilov, S.A.; Conjusteau, A.; Oraevsky, A.A. Whole-body three-dimensional optoacoustic tomography system for small animals. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009, 14, 064007.

- Yang, J.-M.; Maslov, K.; Yang, H.-C.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; Wang, L. Photoacoustic endoscopy. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 1591–1593.

- Wang, B.; Su, J.L.; Amirian, J.; Litovsky, S.H.; Smalling, R.; Emelianov, S. Detection of lipid in atherosclerotic vessels using ultrasound-guided spectroscopic intravascular photoacoustic imaging. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 4889–4897.

- Sethuraman, S.; Aglyamov, S.R.; Amirian, J.H.; Smalling, R.W.; Emelianov, S.Y. Intravascular photoacoustic imaging using an IVUS imaging catheter. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2007, 54, 978–986.

- Jansen, K.; Van Der Steen, A.F.W.; Van Beusekom, H.; Oosterhuis, J.; van Soest, G. Intravascular photoacoustic imaging of human coronary atherosclerosis. Opt. Lett. 2011, 36, 597–599.

- Wang, H.W.; Chai, N.; Wang, P.; Hu, S.; Dou, W.; Umulis, D.; Wang, L.V.; Sturek, M.; Lucht, R.; Cheng, J.X. Label-free bond-selective imaging by listening to vibrationally excited molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 238106.

- Wei, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; Chen, Z. Integrated ultrasound and photoacoustic probe for co-registered intravascular imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 106001.

- Wang, P.; Wang, H.-W.; Sturek, M.; Cheng, J.-X. Bond-selective imaging of deep tissue through the optical window between 1600 and 1850 nm. J. Biophotonics 2012, 5, 25–32.

- Ansari, R.; Zhang, E.Z.; Desjardins, A.E.; Beard, P.C. All-optical forward-viewing photoacoustic probe for high-resolution 3D endoscopy. Light. Sci. Appl. 2018, 7, 1–9.

- Mathews, S.J.; Little, C.; Loder, C.D.; Rakhit, R.D.; Xia, W.; Zhang, E.Z.; Beard, P.C.; Finlay, M.; Desjardins, A.E. All-optical dual photoacoustic and optical coherence tomography intravascular probe. Photoacoustics 2018, 11, 65–70.

- Wissmeyer, G.; Pleitez, M.A.; Rosenthal, A.; Ntziachristos, V. Looking at sound: Optoacoustics with all-optical ultrasound detection. Light. Sci. Appl. 2018, 7, 53.

- Chen, Z.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xing, D. Noncontact broadband all-optical photoacoustic microscopy based on a low-coherence interferometer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 043701.

- Guo, Z.; Li, G.; Chen, S.-L. Miniature probe for all-optical double gradient-index lenses photoacoustic microscopy. J. Biophotonics 2018, 11, e201800147.

- Li, G.; Guo, S.L.Z. Chen, Miniature all-optical probe for large synthetic aperture photoacoustic-ultrasound imaging. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 25023–25035.

- Sheaff, C.; Ashkenazi, S. An all-optical thin-film high-frequency ultrasound transducer. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, Orlando, FL, USA, 18–21 October 2011; pp. 1944–1947.

- Preisser, S.; Rohringer, W.; Liu, M.; Kollmann, C.; Zotter, S.; Fischer, B.; Drexler, W. All-optical highly sensitive akinetic sensor for ultrasound detection and photoacoustic imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2016, 7, 4171–4186.

- Roggan, A.; Friebel, M.; Dörschel, K.; Hahn, A.; Müller, G. Optical Properties of Circulating Human Blood in the Wavelength Range 400–2500 nm. J. Biomed. Opt. 1999, 4, 36–46.

- Anderson, R.R.; Farinelli, W.; Laubach, H.; Manstein, D.; Yaroslavsky, A.N.; Gubeli, J.; Jordan, K.; Neil, G.R.; Shinn, M.; Chandler, W.; et al. Selective photothermolysis of lipid-rich tissues: A free electron laser study. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006, 38, 913–919.

- Tsai, C.-L.; Chen, J.-C.; Wang, W.-J. Near-infrared Absorption Property of Biological Soft Tissue Constituents. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2001, 21, 7–14.

- Available online: http://omlc.ogi.edu/spectra (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Jansen, K.; Van Der Steen, A.F.W.; Wu, M.; Van Beusekom, H.M.M.; Springeling, G.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; De Kleijn, D.P.V.; van Soest, G. Spectroscopic intravascular photoacoustic imaging of lipids in atherosclerosis. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 026006.

- Jansen, K.; Wu, M.; van der Steen, A.F.; van Soest, G. Lipid detection in atherosclerotic human coronaries by spectroscopic intravascular photoacoustic imaging. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 21472–21484.

- Yao, J.; Maslov, K.; Zhang, Y.S.; Xia, Y.; Wang, L. Label-free oxygen-metabolic photoacoustic microscopy in vivo. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 076003.

- Yang, J.-M.; Favazza, C.; Chen, R.; Yao, J.; Cai, X.; Maslov, K.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; Wang, L. Simultaneous functional photoacoustic and ultrasonic endoscopy of internal organs in vivo. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1297–1302.

- Li, Y.; Lu, G.; Chen, J.; Jing, J.C.; Huo, T.; Chen, R.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Z. PMN-PT/Epoxy 1-3 composite based ultrasonic transducer for dual-modality photoacoustic and ultrasound endoscopy. Photoacoustics 2019, 15, 100138.

- Yang, J.-M.; Chen, R.; Favazza, C.; Yao, J.; Li, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; Wang, L. A 25-mm diameter probe for photoacoustic and ultrasonic endoscopy. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 23944–23953.

- He, H.; Stylogiannis, A.; Afshari, P.; Wiedemann, T.; Steiger, K.; Buehler, A.; Zakian, C.; Ntziachristos, V. Capsule optoacoustic endoscopy for esophageal imaging. J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800439.

- Li, X.; Xiong, K.; Yang, S. Large-depth-of-field optical-resolution colorectal photoacoustic endoscope. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 114, 163703.

- Xiong, K.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Xing, D. Autofocusing optical-resolution photoacoustic endoscopy. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 1846–1849.

- Jin, D.; Yang, F.; Chen, Z.; Yang, S.; Xing, D. Biomechanical and morphological multi-parameter photoacoustic endoscope for identification of early esophageal disease. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 103703.

- Yang, J.-M.; Li, C.; Cheng-Hung, Y.; Rao, B.; Yao, J.; Yeh, C.-H.; Danielli, A.; Maslov, K.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; et al. Optical-resolution photoacoustic endomicroscopy in vivo. Biomed. Opt. Express 2015, 6, 918–932.

- Liu, N.; Yang, S.; Xing, D. Photoacoustic and hyperspectral dual-modality endoscope. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 138–141.

- Basij, M.; Yan, Y.; Alshahrani, S.S.; Helmi, H.; Burton, T.K.; Burmeister, J.W.; Dominello, M.M.; Winer, I.S.; Mehrmohammadi, M. Miniaturized phased-array ultrasound and photoacoustic endoscopic imaging system. Photoacoustics 2019, 15, 100139.

- Yuan, Y.; Yang, S.; Xing, D. Preclinical photoacoustic imaging endoscope based on acousto-optic coaxial system using ring transducer array. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 2266–2268.

- Guo, H.; Song, C.; Xie, H.; Xi, L. Photoacoustic endomicroscopy based on a MEMS scanning mirror. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 4615–4618.

- Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Jing, J.C.; Chen, J.J.; Heidari, A.E.; He, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ma, T.; Yu, M.; Zhou, Q.; et al. High-Speed Integrated Endoscopic Photoacoustic and Ultrasound Imaging System. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2019, 25, 1–5.

- Ji, X.; Xiong, K.; Yang, S.; Xing, D. Intravascular confocal photoacoustic endoscope with dual-element ultrasonic transducer. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 9130–9136.

- Li, X.; Wei, W.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; Chen, Z. Intravascular photoacoustic imaging at 35 and 80 MHz. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 1060051.

- Piao, Z.; Ma, T.; Li, J.; Wiedmann, M.T.; Huang, S.; Yu, M.; Shung, K.K.; Zhou, Q.; Kim, C.-S.; Chen, Z. High speed intravascular photoacoustic imaging with fast optical parametric oscillator laser at 1.7 μm. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 083701.

- Wang, B.; Karpiouk, A.; Yeager, D.; Amirian, J.; Litovsky, S.; Smalling, R.; Emelianov, S. In vivo Intravascular Ultrasound-guided Photoacoustic Imaging of Lipid in Plaques Using an Animal Model of Atherosclerosis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2012, 38, 2098–2103.

- Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Ji, X.; Zhou, Q.; Xing, D. Characterization of lipid-rich aortic plaques by intravascular photoacoustic tomography: Ex vivo and in vivo validation in a rabbit atherosclerosis model with histologic correlation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 385–390.

- Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Yang, F.; Yang, S.; Xing, D. Intravascular tri-modality system: Combined ultrasound, photoacoustic, and elasticity imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 113, 253701.

- Xie, Z.; Shu, C.; Yang, D.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.; Dai, G.; Lam, K.H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Sheng, Z.; et al. In vivo intravascular photoacoustic imaging at a high speed of 100 frames per second. Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 6721–6731.

- Hui, J.; Yu, Q.; Ma, T.; Wang, P.; Cao, Y.; Bruning, R.S.; Qu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Sturek, M.; et al. High-speed intravascular photoacoustic imaging at 1.7 μm with a KTP-based OPO. Biomed. Opt. Express 2015, 6, 4557–4566.

- Wu, M.; Springeling, G.; Lovrak, M.; Mastik, F.; Iskander-Rizk, S.; Wang, T.; Van Beusekom, H.M.M.; Van Der Steen, A.F.W.; Van Soest, G. Real-time volumetric lipid imaging in vivo by intravascular photoacoustics at 20 frames per second. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 943–953.

- Lei, P.; Wen, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P.; Yang, S. Ultrafine intravascular photoacoustic endoscope with a 07 mm diameter probe. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 5406–5409.

- Bai, X.; Gong, X.; Hau, W.; Lin, R.; Zheng, J.; Liu, C.; Zeng, C.; Zou, X.; Zheng, H.; Song, L. Intravascular Optical-Resolution Photoacoustic Tomography with a 1.1 mm Diameter Catheter. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92463.

- Li, Y.; Gong, X.; Liu, C.; Lin, R.; Hau, W.; Bai, X.; Song, L. High-speed intravascular spectroscopic photoacoustic imaging at 1000 A-lines per second with a 0.9-mm diameter catheter. J. Biomed. Opt. 2015, 20, 065006.

- Xiong, K.; Wang, W.; Guo, T.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, S. Shape-adapting panoramic photoacoustic endomicroscopy. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 2681–2684.

- Vanderlaan, D.; Karpiouk, A.B.; Yeager, D.; Emelianov, S. Real-Time Intravascular Ultrasound and Photoacoustic Imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2017, 64, 141–149.

- Yang, J.-M.; Li, C.; Chen, R.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; Wang, L. Catheter-based photoacoustic endoscope. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 066001.

- Qu, Y.; Li, C.; Shi, J.; Chen, R.; Xu, S.; Rafsanjani, H.; Maslov, K.; Krigman, H.; Garvey, L.; Hu, P.; et al. Transvaginal fast-scanning optical-resolution photoacoustic endoscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2018, 23, 121617.

- Dong, B.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, C.; Zhang, H.F. Photoacoustic probe using a microring resonator ultrasonic sensor for endoscopic applications. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 4372–4375.

- Edward, Z.Z.; Paul, C.B. A miniature all-optical photoacoustic imaging probe. In Proceedings of the Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2011, San Francisco, CA, USA, 28 February 2011.

- Wang, P.; Ma, T.; Slipchenko, M.N.; Liang, S.; Hui, J.; Shung, K.K.; Roy, S.; Sturek, M.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Z.; et al. High-speed Intravascular Photoacoustic Imaging of Lipid-laden Atherosclerotic Plaque Enabled by a 2-kHz Barium Nitrite Raman Laser. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6889.

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Cheng, J.-X. High-resolution photoacoustic endoscope through beam self-cleaning in a graded index fiber. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 3841–3844.

- Wang, L.; Lei, P.; Wen, X.; Zhang, P.; Yang, S. Tapered fiber-based intravascular photoacoustic endoscopy for high-resolution and deep-penetration imaging of lipid-rich plaque. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 12832–12840.

- Karpiouk, A.B.; Wang, B.; Amirian, J.; Smalling, R.W.; Emelianov, S.Y. Feasibility of in vivo intravascular photoacoustic imaging using integrated ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging catheter. J. BioMed. Opt. 2012, 17, 96008.

- Cao, Y.; Hui, J.; Kole, A.; Wang, P.; Yu, Q.; Chen, W.; Sturek, M.; Cheng, J.-X. High-sensitivity intravascular photoacoustic imaging of lipid–laden plaque with a collinear catheter design. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25236.

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, Z. Multimodality Imaging; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020.

- Jansen, K. Intravascular Photoacoustics; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2013.