| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marta Valverde | + 3935 word(s) | 3935 | 2021-07-26 05:38:37 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 3935 | 2021-08-05 14:30:30 | | |

Video Upload Options

Participative decision making (PDM) is the opportunity for an employee to provide input into the decision-making process related to work matters (i.e., work organization, task priority) or organizational issues, for example, when they have a say on promoting new strategy ideas. Elele and Fields state that PDM is a management initiative based on the ”theory Y”, which suggests that employees are interested in being committed and performing well if managers value their contributions in making decisions that affect the nature of work. The diverse opportunities to participate in the decision-making process can provide mutual benefits for employees and employers. Some writers have proposed that PDM enhances motivation, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. The literature frames employee participation in different contexts, depending on the political, social, and legal environment of the countries.

1. Participative Decision Making (PDM)

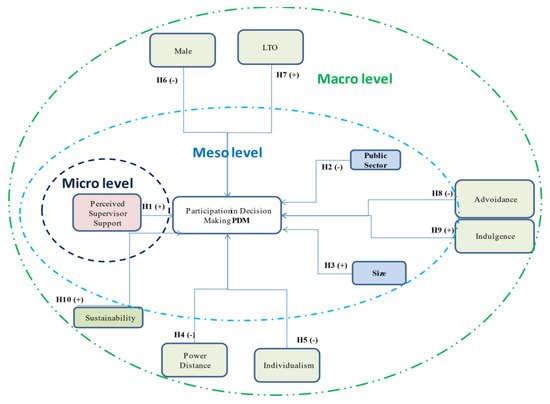

As commented in the introduction, the variable to be explained is the direct participation of the employee, at a general level, as well as distinguishing the scope of the decisions in which employees participate (operational and organizational) based on a range of variables at the micro (employee), meso (organization), and macro (cultural and sustainability indexes) levels. This structure per level could be visualized in Figure 1, which appears at the end of this section. The content of each of these variables is detailed below. Participative decision making (PDM) is the opportunity for an employee to provide input into the decision-making process related to work matters [1] (i.e., work organization, task priority) or organizational issues, for example, when they have a say on promoting new strategy ideas. Elele and Fields [2] state that PDM is a management initiative based on the ”theory Y”, which suggests that employees are interested in being committed and performing well if managers value their contributions in making decisions that affect the nature of work. The diverse opportunities to participate in the decision-making process can provide mutual benefits for employees and employers. Some writers have proposed that PDM enhances motivation [3][4], organizational commitment, and job satisfaction [5][6]. The literature frames employee participation in different contexts, depending on the political, social, and legal environment of the countries [7]. That is why other terms coexist with “employee participation” and are used similarly at the heart of PDM. These other terms include employee “voice”, “engagement”, “involvement”, or “empowerment”. Although there are some differences among these concepts [8][9][10], all share a common central point—to describe an environment in which employees can decide and act on what impacts their work and organizational decisions. According to [11], PDM is the same thing as employee involvement in decision making.

Figure 1. Research model.

Previous researchers identify a fourfold framework to classify participative practices [12] in terms of degree, form, level, and scope. First, the degree indicates whether employees are simply informed, consulted, or involved about news or changes in the business. In other words, the degree is the extent to which employees can influence decisions. Second, the form represents whether participation is promoted by company initiatives or workers’ union representation. In the first scenario, it takes the form of direct employee participation (suggestion schemes, staff surveys, informal or formal meetings, and quality circles are some examples of direct participation) and evolves all the activities driven by managers and organizations to allow employees to have a say in decision making. On the other hand, when trade unions act as intermediaries and give voice to employees through their representation, the form of participation is categorized as indirect [13]. Third, previous researchers differentiate whether participation takes place at the individual, group, or department level [12]. Fourth, the scope, which is about the subject decision, distinguishes a wide range of issues related to operational concerns, such as how to improve practices on the manufacturing line [14] and strategic matters, when they are related to organizational decision-making processes such as mergers or mission and organizational goals [15]. Precisely, the scope is the approach used in this article to differentiate kinds of PDM.

Regarding the scope of employee participation, it can be said that it has been transformed with the evolution of industrial relations. At the beginning of the decade of the 1980s, employees could take part in decisions that affected their immediate work. This was called task discretion, which according to the definition of Kalleberg et al. [16] is ‘‘to participate in making decisions about their jobs and working conditions”. In this line, many organizations tried to give autonomy to employees to develop their skills and make decisions regarding their tasks, time, and work conditions. This is also known as job autonomy and involves the different ways in which an employee can develop their tasks with freedom. These concepts are related to operational PDM, which occurs when employees have a voice in their immediate job. As Sia et al. [17] point out, when an organization provides enough freedom for employees in their task, it positively influences their creativity and performance. Although task discretion currently exists, workplaces suffered a management transformation during the 1990s with the transition to a knowledge-based economy that allows employee views in decision making related to strategic issues, which are those related to business goals. It is precisely this direct consultation that has become the central theme where managers allow employees to influence organizational issues. In the literature, the extent to which employees can decide on organizational or strategic matters is referred to as organizational participation [18][19].

From the human resources perspective, the current paper focuses on PDM as direct employee participation, which is referred to as an employer-leading tool that allows employees to take part in decision-related operational and organizational matters. This definition is supported by [20][21], who indicate that employee participation refers to the extent to which employees are allowed or encouraged to share their views and ideas about organizational activities or provide their input in organizational decision making. The present study intends to explore whether there are noticeable differences among all the determinant variables and the scope of the decision.

2. Micro Level: Perceived Supervisor Support

Previous researchers support that consensual and participative decision making are proper in modern companies that need to effectively respond to change [22][23]. Given that direct employee participation is an employer-driven initiative, managers gain special attention as promoters (or detractors) of employee participation. According to Blau [24][25], social exchange theory (PDM) states the basis for a social exchange that goes beyond the standard economic contract. Previous studies on decision making have focused on superior–subordinate communication [26][27]. Analyzing this combination, Torka et al. [28] pointed out that a good relationship between managers and employees will increase employee involvement. A recent study developed by Wohlgemuth et al. [29] finds that managers can facilitate employee participation through both trust in and informal control of subordinates. Regarding operational decision making, a study by Humphrey and colleagues showed consistent positive relationships between social support and interdependence [30]. In line with these approaches, a manager will determine if an employee is only informed of or involved in the decision-making process. Although this positive relationship was studied previously [31], the current study explored whether this link occurs in terms of the scope. This leads to the proposition that there exists a positive relationship between PSS and employee participation at all its levels:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

PSS relates positively to operational direct employee participation.

3. Meso Level: Ownership and Size

The decision-making process is different under public or private ownership and depends on the roles that those kinds of organizations play in our society. According to Nutt [32], private sector organizations sell products or services to consumers in markets to create wealth for shareholders. In contrast, public organizations are governmental agencies that deliver contracts for services and collect information about the needs of a society [33]. The decision-making processes in these types of organizations are different. Specifically, these differences were studied by Nutt, who concluded they were related to political influence, data availability, ownership, and goals. Each of these statements is also supported by more studies in the literature.

In terms of political influence, a study by Shaed et al. [34] reveals that the decision making of public organizations gives the power to decide to political forces, placing political concerns above economic issues. In addition, it states that wide levels of decision and bureaucracy exist, which makes it a slower and more time-consuming process. Another distinction between the sectors is related to data collection [32]. The private sector has the chance to buy more information from the market, which gives it more autonomy and flexibility in the decision-making process, while access to data is difficult for the public sector. Brown et al. [35] support that employee participation and practices implemented to increase productivity and profitability may be particularly strong in the private sector. Nutt and Backoff [36] analyzed differences in goal setting. In this sense, goals in the private sector are often clear and follow efficiency; however, those in the public sector are complex and conflict-ridden, increasing the time required to make decisions. Specifically, the complexities of the public sector make the promotion of strategic decision making difficult, because legislation prohibits political leaders from collecting information from the market. However, regarding the large autonomy that public employees have [37], operational decision-making is expected to be promoted by the public sector. Hence, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Organizational size is another meso variable and distinguishes between small, medium, and large organizations according to business activity. Human resource practices vary depending on the size of the company. Kersley et al. [38] consider that forms of direct employee participation are more common in large companies. This rationale is in line with previous authors who state that larger organizations are more participative than smaller organizations [39]. Considering these antecedents, it seems clear that organizational size could have significance for PDM. In terms of scope, it is precise to differentiate between business orientation and organizational size. This may be because larger companies have a strategic orientation. A study assessed by McEvoy and Buller in 2013 found that HR in larger firms was more strategic and less operational than HR in small and mid-sized firms [40]. Under this premise and considering that PDM is an HR practice, it is expected that large companies promote organizational decisions. Research into organizational size also supports that larger structures decrease employee autonomy in the workplace [41]. Thus, it is expected that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

Organization size is negatively related to operational PDM.

4. Macro Level: Cultural Values and Sustainability

The literature focused on strategy highlights that the macro environment is made up of all the social, legal, political, economic, and cultural factors that affect organizations [42][43][44]. In other words, the environment sets guidelines for the exercise of business activity. Coyle-Shapiro and Shore [45] postulated that major external environmental changes accelerate the evolution of sociocultural values by altering the relationship between the organization and its employees and affecting employee responses to an organization’s policies and practices. The need to incorporate a cross-cultural approach to the reality of companies is explained by [46]: “Each country has unique institutional and cultural characteristics that provide sources of competitive advantage that are only reliable when there are changes in the environment. Managers, therefore, need to assess the extent of the national culture that may interfere with their company efforts to respond with the appropriate strategy now and in the future” (p9). In other words, national culture theory could be used as a framework for researching many areas such as business management, and it also conditions the decision-making process [47]. Furthermore, culture determines values and behaviors that individuals reflect in the organizations [48]. To expand this approach, Hofstede scores have been considered for the analysis since they represent the most valuable reference for cross-cultural studies [49]. In addition to culture, and considering the increase for caring the environment and how employees are involved in green activities at organizations [50], sustainability has been added as another macro variable. In the following sections, all the macro variables (cultural and sustainability) are analyzed.

4.1. Power Distance

This dimension refers to the power distribution among the members of institutions and organizations within a country [51]. In organizations, power distance (PD) is represented by strong hierarchical structures where power is mainly developed by managers and leaders, while employees feel comfortable in a bureaucratic atmosphere. In contrast, in low power distance cultures, managers tend to delegate the decision-making process [52], so employees feel that the power to make decisions is shared at the same level among all people integrated into the organization [53]. In a scenario of high power distance cultures, managers are not willing to share goal setting with employees [54], and employees are fearful of expressing their views and seek to avoid conflict [55]. This leads us to the formulation of the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

The higher the level ofpower distance, the lowerthe level of employee operational participation in that country.

4.2. Individualism–Collectivism

This Hofstede dimension is related to the differentiation of group versus individual interests. Individualistic cultures focus on self-concept, freedom, and individual rights. In contrast, collectivistic countries are characterized by a spirit of membership, where values, goals, and interests are respected by all the members of a country. Adopting this approach to work organizations, two main structures can be distinguished in the way people work. Therefore, when work is developed from an autonomous perspective, employees act as individuals. Previous research has found that individualistic cultures promote more autonomy at work than collectivistic cultures [56][57]. In contrast, teamwork and collaboration between members is a common practice for collectivist organizations [58]. Regarding the decision-making process, this paper expects that individualistic countries promote greater autonomy in the daily tasks of an organization, which indicates a positive relationship between individualism and operational decision making. On the other hand, collectivistic cultures help promote teamwork and knowledge sharing [59], which are positively related to organizational decision making. In line with these affirmations, this study proposes:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

The higher the level of individualism, the higher the level of operational employee participation in that country.

4.3. Masculinity–Femininity

This cultural value is defined according to the gender dimension. Historically, human behavior has been analyzed by gender, distinguishing between values more pronounced in women than in men. According to Wu [60], empathy, family, participation, and care are values that have been especially attributed to women. In contrast, monitorization, autocratic leadership, and pursuit of material goals are standards more commonly followed by countries characterized by male values. In line with the gender approach, this study considers that female values will promote employee participation the most because women promote interpersonal relationships [61]. In the case of operational participation, [62] indicates that male managers are more likely to apply a task-oriented style, which means that they define the time and goals of the tasks. According to this appreciation, male managers are expected to not promote task discretion due to their tendency to monitor work. Additionally, in terms of leadership, women tend to adopt a democratic style, which promotes employee participation in decision making. From a strategic point of view, it is expected that women encourage employees to participate in the decision-making process related to organizational matters:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Hypothesis 6a (H6a).

Hypothesis 6b (H6b).

The higher the level of male values in the country where the organization is located, the lower the level of organizational employee participation.

4.4. Time Orientation

The cultural literature mainly recognizes time in terms of the length of short- or long-term planning. This cultural dimension accounts for how countries focus on the future. Countries with a long-term orientation are aware of the future, so members of these countries believe in perseverance, resource maintenance, and thrift. Luria et al. pointed out that “in societies with a long term orientation, people expect to have more interaction with others in the future and are consequently more willing to help others” [63] (p. 7). According to this rationale, employees will be encouraged to participate in decision making in organizations located in countries with a long-term orientation. Based on the nature of decisions, previous researchers have aligned long-term orientation with the strategic decision-making process [64][65]. Moreover, Qian et al. [66] explain that employees with a future orientation are engaged in goal setting. For that reason, it is expected that employee participation in organizational decisions is positively related. In contrast, a short-term approach emphasizes proximate returns and planning in the moment [67][68], which seems to be related to operational involvement. Following this logic, it is expected that:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Hypothesis 7a (H7a).

Hypothesis 7b (H7b).

The higher the level of long-term orientation in the country where the organization is located, the greater the organizational employee participation in that organization.

4.5. Uncertainty Avoidance

This cultural dimension reflects a society’s tolerance for dealing with ambiguous and risky situations. In countries with high uncertainty avoidance, organizations create rules that control the rights and duties of employees. In contrast, countries with low uncertainty avoidance prefer fewer rules and feel comfortable in risky situations [69]. In practice, employees who work with low uncertainty avoidance are not afraid of changes. However, under high uncertainty avoidance situations, employees prefer obligations and rules defined by management [70]. In countries with a high uncertainty level, employees need routines that reduce uncertainty regarding task-related matters [71]. Therefore, employees avoid making their own decisions about their tasks. Regarding organizational decision making, Hood and Logsdon 2002 [72] point out that employees will participate less in contexts of high uncertainty. Previous arguments confirm that uncertainty avoidance will decrease employees’ opportunities to participate in decision making, either operational or strategic. Consequently, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Hypothesis 8a (H8a).

Hypothesis 8b (H8b).

The higher the level of uncertainty avoidance, the lower the level of operational employee participation in that country.

4.6. Indulgence

Indulgence versus restraint is the latest dimension included by Hofstede. The cultural value of indulgence is defined by the level of happiness and enjoyment in life exhibited by a society, while high levels of restraint are featured by behavioral discipline [73]. Regarding decision making, people from restraint-oriented cultures tend to be moderate [74]. Although previous research found a significant and positive relationship between PDM and indulgence [75], this dimension has been particularly unexplored. This study expects a positive and direct relationship between indulgence and all forms of PDM:

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Hypothesis 9a (H9a).

Hypothesis 9b (H9b).

The higher the level of indulgence, the higher the level of operational employee participation in that country.

4.7. Sustainability

In addition to culture, organizations receive external pressure from different regulatory and social drivers that influence change in organizations. Institutional theory helps to analyze the factors that encourage organizations to adapt to the social norms of the business environment [76][77]. The way that organizations adapt their business to the external environment is called an isomorphism.

Institutional theory defines three forms of drivers that are conducive to isomorphism in an organization [78]: normative, coercive, and mimetic isomorphic drivers. Normative isomorphism occurs when organizations follow similar practices promoted by professionals of the sector [79]. Coercive isomorphism compiles all norms, rules, and regulative pressure that influence change. Mimetic influence takes place when organizations imitate the actions of successful competitors to achieve similar environmental standards. According to DiMaggio and Powell [78], three forces within organizations and the environment promote convergent business practices, which affect organizational decision making [80] and explain the sustainable initiatives of organizations. According to Renukappa et al. [81], the literature on institutional theory facilitates an understanding of how changes in government regulation, technology, competitors, and stakeholders affect the way organizations innovate their business model to be more sustainable [82][83][84]. This approach is supported by Campbell [85], who states that the existence of regulations tends to affect the organization´s social responsibility initiatives.

This idea affirms that countries’ institutional factors and regulations condition the reality and development of organizations. As occurs with cultural values, organizations’ sustainable activities reflect the level of sustainability of the country. At the country level, sustainability is part of a competitiveness index that measures how countries behave in terms of sustainable development (WCY, 2015) [86]; that is, how a country is committed to the environment and the development of its infrastructure without compromising its resources. This construct extrapolates to organizations through social responsibility and the different initiatives that promote sustainable behavior. Social responsibility in companies has gained relevance in recent years as society has increased its awareness of sustainable matters. This means that organizations have to reach long-term development to achieve their goals while pursuing a balance between all the invested resources [87]. Sustainable organizations extend their sustainable values to all their structures. When human resources management adopts a sustainable approach in all its practices (recruitment, training, onboarding, etc.), it is referred to as sustainable human resources management (SHRM) or green human resources management (GHRM).

According to [88], employee empowerment is one type of green human resources management (GHRM) practice, such as training and selection. Additionally, sharing knowledge about environmental initiatives or joint consultation are other examples of HR green practices. According to this rationale, previous research has shown that employee participation is a key element for sustainable initiatives [89][90]. In this sense, it is useful for organizations to count on employee activity for volunteering or ecologic practices. However, there is a lack of empirical research about whether sustainable practices promote employee participation for any kind of issue. For that reason, it is expected that sustainable organizations also promote participative initiatives related to all types of issues (organizational and operational) based on the level of sustainability of the country. In this study, since we do not have a sustainability indicator at the company level, we will use as an approximation the value of the sustainability indicator of the country in which the organizations are located, so:

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Hypothesis 10a (H10a).

Hypothesis 10b (H10b).

The sustainability levels of the country where organizations are located are positively related to operational employee participation.

References

- Zanoni, P.; Janssens, M. Minority employees engaging with (diversity) management: An analysis of control, agency, and micro-emancipation. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 1371–1397.

- Elele, J.; Fields, D. Participative decision making and organizational commitment: Comparing Nigerian and American employees. Cross Cult. Manag. 2010, 17, 368–392.

- Boxall, P.; Hutchison, A.; Wassenaar, B. How do high-involvement work processes influence employee outcomes? An examination of the mediating roles of skill utilisation and intrinsic motivation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 26, 1737–1752.

- Tian, X.; Zhai, X. Employee involvement in decision-making: The more the better? Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 768–782.

- Bhatti, K.K.; Qureshi, T.M. Impact of Employee Participation on Job Satisfaction, Employee Commitment and Employee Productivity. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Pap. 2007, 3, 54–68.

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Louis, D.; Makarenko, D.; Saluja, J.; Meleshko, O.; Kulbashian, S. Participation in decision making: A case study of job satisfaction and commitment (part three). Ind. Commer. Train. 2013, 45, 412–419.

- Wilkinson, A.; Gollan, P.J.; Marchington, M.; Lewin, D. Conceptualizing Employee Participation in Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010.

- Lavelle, J.; Gunnigle, P.; McDonnell, A. Patterning employee voice in multinational companies. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 395–418.

- Wilkinson, A.; Gollan, P.J.; Kalfa, S.; Xu, Y. Voices unheard: Employee voice in the new century. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 711–724.

- Zaware, N.; Pawar, A.; Kale, S.; Fauzi, T.; Loupias, H. Deliberating the managerial approach towards employee participation in management. Int. J. Control Autom. 2020, 13, 437–457.

- Ugwu, K.E.; Okoroji, L.I.; Chukwu, E.O. Participative decision making and employee performance in the hospitality industry: A study of selected hotels in Owerri Metropolis, Imo State. Manag. Stud. Econ. Syst. 2019, 4, 57–70.

- Marchington, M.; Wilkinson, A. Direct Participation and Involvement. Manag. Hum. Resour. Pers. Manag. Transit. 2005, 398–423.

- Markey, R.; Townsend, K. Contemporary trends in employee involvement and participation. J. Ind. Relat. 2013, 55, 475–487.

- Viveros, H.; Kalfa, S.; Gollan, P.J. Voice as an empowerment practice: The case of an Australian manufacturing company. In Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2018.

- Knudsen, H.; Busck, O.; Lind, J. Work environment quality: The role of workplace participation and democracy. Work. Employ. Soc. 2011, 25, 379–396.

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Nesheim, T.; Olsen, K.M. Is participation good or bad for workers?: Effects of autonomy, consultation and teamwork on stress among workers in norway. Acta Sociol. 2009, 52, 99–116.

- Sia, S.K.; Appu, A.V. Work Autonomy and Workplace Creativity: Moderating Role of Task Complexity. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2015, 16, 772–784.

- Inanc, H.; Zhou, Y.; Gallie, D.; Felstead, A.; Green, F. Direct Participation and Employee Learning at Work. Work Occup. 2015, 42, 447–475.

- Busck, O.; Knudsen, H.; Lind, J. The transformation of employee participation: Consequences for the work environment. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2010, 31, 285–305.

- Miller, G.R. “Gender Trouble”: Investigating gender and economic democracy in worker cooperatives in the united states. Rev. Radic. Polit. Econ. 2012, 44, 8–22.

- Carmeli, A.; Sheaffer, Z.; Halevi, M.Y. Does participatory decision-making in top management teams enhance decision effectiveness and firm performance? Pers. Rev. 2009, 38, 696–714.

- Carson, J.B.; Tesluk, P.E.; Marrone, J.A. Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1217–1234.

- Pearce, C.L.; Conger, J.A.; Locke, E.A. Shared leadership theory. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 622–628.

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Bock, G.W., Young-Gul, K., Eds.; Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964.

- Blau, P.M. The Dynamics of Bureaucracy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1955.

- Andrews, M.C.; Kacmar, K.M. Discriminating among organizational politics, justice, and support. J. Organ. Behav. 2001, 22, 347–366.

- Abu Bakar, H.; Mohamad, B.; Herman, I. Leader-Member Exchange and Superior-Subordinate Communication Behavior: A Case of a Malaysian Organization. Malays. Manag. J. 2020, 8, 83–93.

- Torka, N.; Schyns, B.; Looise, J.K. Direct participation quality and organisational commitment: The role of leader-member exchange. Empl. Relat. 2010, 32, 418–434.

- Wohlgemuth, V.; Wenzel, M.; Berger, E.S.C.; Eisend, M. Dynamic capabilities and employee participation: The role of trust and informal control. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 760–771.

- Humphrey, S.E.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P. Integrating Motivational, Social, and Contextual Work Design Features: A Meta-Analytic Summary and Theoretical Extension of the Work Design Literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1332–1356.

- Valverde-Moreno, M.; Torres-Jiménez, M.; Lucia-Casademunt, A.M.; Muñoz-Ocaña, Y. Cross cultural analysis of direct employee participation: Dealing with gender and cultural values. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–13.

- Nutt, P.C. Comparing public and private sector decision-making practices. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2006, 16, 289–318.

- Bercu, A. Strategic Decision Making in Public Sector: Evidence and Implications. Acta Univ. Danubius Acon. 2013, 9, 21–27.

- Shaed, M.M.B.; Zainol, I.N.B.H.; Yusof, M.B.M.; Bahrin, F.K. Types of Employee Participation in Decision Making (PDM) amongst the Middle Management in the Malaysian Public Sector. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 603–613.

- Brown, M.; Geddes, L.A.; Heywood, J.S. The determinants of employee-involvement schemes: Private sector Australian evidence. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2007, 28, 259–291.

- Nutt, P.C.; Backoff, R.W. Organizational publicness and its implications for strategic management. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1993.

- Diller, M. The Revolution in Welfare Administration: Rules, Discretion & Entrepreneurial Government. SSRN Electron. J. 2005, 75, 1121.

- Kersley, B.; Alpin, C.; Forth, J.; Bryson, A.; Bewley, H.; Dix, G.; Oxenbridge, S. Inside the Workplace: Findings from the 2004 Workplace Employment Relations Survey; Routledge: London, UK, 2006.

- Cabrera, E.F.; Ortega, J.; Cabrera, Á. An exploration of the factors that influence employee participation in Europe. J. World Bus. 2003, 38, 43–54.

- McEvoy, G.M.; Buller, P.F. Human resource management practices in mid-sized enterprises. Am. J. Bus. 2013, 28, 86–105.

- Lopes, H.; Calapez, T.; Lopes, D. The determinants of work autonomy and employee involvement: A multilevel analysis. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2015, 38, 448–472.

- Calantone, R.J.; Kim, D.; Schmidt, J.B.; Cavusgil, S.T. The influence of internal and external firm factors on international product adaptation strategy and export performance: A three-country comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 176–185.

- Banham, H.C. External Environmental Analysis for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2010.

- Kuznetsova, S.; Markova, V. New Challenges in External Environment and Business Strategy: The Case of Siberian Companies. Eurasian Stud. Bus. Econ. 2017, 4, 449–461.

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.M.; Shore, L.M. The employee-organization relationship: Where do we go from here? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 166–179.

- Schneider, S.C. Barsoux, J. Managing Across Cultures; Financial Times Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2003.

- Albaum, G.; Yu, J.; Wiese, N.; Herche, J.; Evangelista, F.; Murphy, B. Culture-based values and management style of marketing decision makers in six Western Pacific Rim countries. J. Glob. Mark. 2010, 23, 139–151.

- Gelfand, M.J.; Erez, M.; Aycan, Z. Cross-cultural organizational behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 479–514.

- Hofstede, G. Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 1984, 1, 81–99.

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J. The role of employees’ leadership perceptions, values, and motivation in employees’ provenvironmental behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 576–587.

- Kirkman, B.; Chen, G.; Farh, J.L.; Chen, Z.X.; Lowe, K. Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 744–764.

- Newburry, W.; Yakova, N. Standardization preferences: A function of national culture, work interdependence and local embeddedness. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 44–60.

- Brockner, J.; Ackerman, G.; Greenberg, J.; Gelfand, M.J.; Francesco, A.M.; Chen, Z.X.; Leung, K.; Bierbrauer, G.; Gomez, C.; Kirkman, B.L.; et al. Culture and Procedural Justice: The Influence of Power Distance on Reactions to Voice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 37, 300–315.

- Kwon, B.; Farndale, E.; Park, J.G. Employee voice and work engagement: Macro, meso, and micro-level drivers of convergence? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 327–337.

- Huang, X.; Van de Vliert, E.; Van der Vegt, G. Breaking the Silence Culture: Stimulation of Participation and Employee Opinion Withholding Cross-nationally. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 459–482.

- O’Connor, D.B.; Shimizu, M. Sense of personal control, stress and coping style: A cross-cultural study. Stress Health 2002, 18, 173–183.

- Nauta, M.M.; Liu, C.; Li, C. A cross-national examination of self-efficacy as a moderator of autonomy/job strain relationships. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 59, 159–179.

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Lawler, J.J.; Avolio, B.J. Leadership, individual differences, and workrelated attitudes: A cross-culture investigation. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 56, 212–230.

- Arpaci, I.; Baloʇlu, M. The impact of cultural collectivism on knowledge sharing among information technology majoring undergraduates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 65–71.

- Wu, M. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions 30 years later: A study of Taiwan and the United States. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2006, 15, 33.

- Melero, E. Are workplaces with many women in management run differently? J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 385–393.

- Fagenson, E.A.; Powell, G.N. Women and Men in Management. Adm. Sci. Q. 1989, 34, 643.

- Luria, G.; Cnaan, R.A.; Boehm, A. National Culture and Prosocial Behaviors: Results from 66 Countries. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2015, 44, 1041–1065.

- Fredrickson, J.W.; Mitchell, T.R. Strategic Decision Processes: Comprehensiveness and Performance in an Industry with an Unstable Environment. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 399–423.

- Forbes, D.P. Managerial determinants of decision speed in new ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 355–366.

- Qian, J.; Lin, X.; Han, Z.R.; Tian, B.; Chen, G.Z.; Wang, H. The impact of future time orientation on employees’ feedback-seeking behavior from supervisors and co-workers: The mediating role of psychological ownership. J. Manag. Organ. 2015, 21, 336–349.

- Hofstede, G. Cultural constraints in management theories. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1993, 7, 81–94.

- Wang, T.; Bansal, P. Social responsibility in new ventures: Profiting from a long-term orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1135–1153.

- Bhagat, R.S.; Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 460.

- Lau, I.; Jie, C.; Zainal, M.; Harun, M.; Djubair, R.A. Effect of Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance on Employees’ Job Performance: Preliminary Findings. J. Technol. Manag. Bus. 2020, 2, 69–82.

- Joiner, T.A. The influence of national culture and organizational culture alignment on job stress and performance: Evidence from Greece. J. Manag. Psychol. 2001, 16, 229–242.

- Hood, J.N.; Logsdon, J.M. Business ethics in the NAFTA countries: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 883–890.

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Sofware of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2010.

- Koc, E.; Ar, A.A.; Aydin, G. The Potential Implications of Indulgence and Restraint on Service. Ecoforum 2017, 6, 2013–2018.

- Valverde-Moreno, M.; Torres-Jimenez, M.; Lucia-Casademunt, A.M. Participative decision-making amongst employees in a cross-cultural employment setting: Evidence from 31 European countries. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 45, 14–35.

- Glover, J.L.; Champion, D.; Daniels, K.J.; Dainty, A.J.D. An Institutional Theory perspective on sustainable practices across the dairy supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 152, 102–111.

- Frynas, J.G.; Yamahaki, C. Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Bus. Ethics 2016, 25, 258–285.

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147.

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.H. An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15.

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Papadopoulos, T.; Hazen, B.; Giannakis, M.; Roubaud, D. Examining the effect of external pressures and organizational culture on shaping performance measurement systems (PMS) for sustainability benchmarking: Some empirical findings. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 63–76.

- Renukappa, S.; Suresh, S.; Gabriel, M. External drivers for business model innovation for sustainability: An institutional theory perspective. J. Technol. Manag. Bus. 2020, 7, 69–82.

- Fernando, Y.; Wah, W.X. The impact of eco-innovation drivers on environmental performance: Empirical results from the green technology sector in Malaysia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2017, 12, 27–43.

- Naidoo, M.; Gasparatos, A. Corporate environmental sustainability in the retail sector: Drivers, strategies and performance measurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 125–142.

- Neri, A.; Cagno, E.; Di Sebastiano, G.; Trianni, A. Industrial sustainability: Modelling drivers and mechanisms with barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 452–472.

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967.

- IMD World Competitiveness Center. World Competiveness Yearbook; IMD World Competitiveness: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2015.

- Elg, M.; Ellström, P.E.; Klofsten, M.; Tillmar, M. Sustainable development in Organizations. Sustain. Dev. Organ. Stud. Innov. Pract. 2015, 1–15.

- Bombiak, E.; Marciniuk-Kluska, A. Green human resource management as a tool for the sustainable development of enterprises: Polish young company experience. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1739.

- Al Mehrzi, N.; Singh, S.K. Competing through employee engagement: A proposed framework. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 831–843.

- Acharya, A.; Jena, L.K. Employee engagement as an enabler of knowledge retention: Resource-based view towards organisational sustainability. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Stud. 2016, 7, 238.