| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Laith Abualigah | + 2071 word(s) | 2071 | 2021-07-22 13:39:26 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 308 word(s) | 2379 | 2021-08-02 09:13:43 | | |

Video Upload Options

Cyberstalking is a growing anti-social problem being transformed on a large scale and in various forms. Cyberstalking detection has become increasingly popular in recent years and has technically been investigated by many researchers. However, cyberstalking victimization, an essential part of cyberstalking, has empirically received less attention from the paper community.

1. Introduction

The Internet has been an integral part of daily life in recent years. The Internet user stats for 2020 show that more than 5 billion Internet users are distributed worldwide [1] ; this indicates that the Internet is used by half of the world’s people. The exponential spread of the Internet and other information and communication technology affect every area of life. The Internet has numerous features that make it attractive and explain its rapid penetration, such as ease of use, immediacy, law restrictions, low cost, and widespread availability [2]. On the other hand, there is a dark side to this increased Internet usage. The anonymous nature (the physical distance from others is irrelevant) of the Internet and using communication technologies gives perpetrators a vast opportunity to commit crimes, so the Internet has become a vital tool for facilitating the creation of the new phenomenon of “cybercrime” [3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14].

Cyberstalking is a cybercrime categorized as a crime and used as computer networks or devices to advance other ends [15]. While there is no widely accepted concept of cyberstalking, there are several guidelines to follow [8][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37]. The most generally accepted definition is that the activities are carried out over the Internet or mobile devices [24]. Some researchers have argued that there is no agreed definition of cyberstalking (virtual) because there is no agreed-upon meaning (physical) [24][38]. The word “cyberstalking” is used interchangeably with “cyberharassment”, “online stalking”, or “online harassment” [24][30][39][40]. The dissemination of threats and false claims, data destruction, computer surveillance, identity stealing, and sexual motives [41][42][43], the persistent pursuit of an attacker using electronic or Internet-capable computers [44], electronic sabotage such as transmitting viruses or spamming, buying products and services in the victims’ names, and sending false messages are all examples of cyberstalking [42][43]. Cyberstalking is a real threat facing our societies today. We should confront this new phenomenon by examining new modalities and looking for solutions to the issue, and reducing its damage to its victims [45][46][47].

2. Background of the Study and Problem Statements

Over the last two decades, the development of the Internet and the exponential growth of the World Wide Web (WWW) have profoundly altered life in contemporary societies [48][49]. Using cyberspace takes up a significant amount of time in many people’s daily lives [50][51][52]. In conjunction with the rapid development of ICTs, the Internet has created a near-perfect arena for crimes to occur [48]. The British Prime Minister, David Cameron, in a 2013 speech to the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), said, “The internet is not only where we buy, sell, and socialize; it’s also where violations occur, and people can be harmed”.

As shown in Table 1 , the increase in the number of Internet users is significant compared to the growth in the population [53]. Therefore, it was not surprising that there is a real rise in the number of cybercrimes in Jordan. Cybercrimes pose a critical problem for the police force and judicial police in Jordan because of the unique technical nature of this crime [54].

| Year | Users | Population | % Pop. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 127,300 | 5,282,558 | 2.4 |

| 2002 | 457,000 | 5,282,558 | 8.7 |

| 2005 | 600,000 | 5,282,558 | 11.4 |

| 2007 | 796,900 | 5,375,307 | 14.8 |

| 2008 | 1,126,700 | 6,198,677 | 18.2 |

| 2009 | 1,595,200 | 6,269,285 | 25.4 |

| 2010 | 1,741,900 | 6,407,085 | 27.2 |

| 2012 | 2,481,940 | 6,508,887 | 38.1 |

| 2020 | 8,700,000 | 10,909,567 | 79.7 |

The objectives of this research are as follows: To estimate the prevalence of cyberstalking victimization among college students. To examine the relationships between L-RAT constructs and cyberstalking victimization. To identify the demographic factors that are linked to the history of cyberstalking victimization. To develop and validate a cyberstalking victimization model.

This paper focuses on students in Jordan. It is well-known that students frequently use the Internet, which exposes them to the risk of becoming a victim of cyberstalking victimization, making them attractive as a sample for this research. In terms of individuals, this research focuses on students registered at Luminus Technical University College (LTUC) to investigate cyberstalking victimization. Including other students from other colleges in the sample would increase the time required for data collection without adding to the quality of the findings. Concerning criminal activities, this study focuses on cybercrime victimization, and specifically, cyberstalking. A group-administered questionnaire was used to collect data and was then evaluated in the SEM system using the partial least squares (PLS) technique. Microsoft Visio and Excel 2010, SmartPLS 2.0, and IBM SPSS 20 were used as analysis tools to develop the conceptual research model. In addition, QSR’s NVivo 10 was used for the systematic literature review conducted in the current research. Lastly, Mendeley software was used as a management tool for references.

3. The Proposed Cyberstalking Victimization Conceptual Model

A conceptual model is a well-specified model showing the fundamental relationships of a given set of variables as hypothesized from the theory [55]. Guba and Lincoln [56] adapted the view by Bamasoud [57], which found in his study that, if the following points are taken into consideration, i.e., the objective reality can be systematically and rationally investigated empirically and guided by the laws applied to social science; the independency of the researcher and the phenomenon being studied; the researcher remains detached; neutral objective; and propositions are generated by theories that are operationalized as hypotheses and have undergone experimental testing that is replicable, then the research is categorized as positivist.

In the current study, these guidelines were used to develop the questionnaire and select the appropriate assessment method. In the policies proposed by Hair et al. [58], four variables (proximity of motivated offenders, a suitable target, digital guardianship and cyberstalking victimization) were specified as reflective constructs (see Table 2 ).

| Construct | Items | Criteria | Reflective/ Formative |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Proximity to Motivated Offenders | Unknown Friend | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective |

| Visiting Religious Websites | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Listening/Downloading Music | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Watching/Downloading Movies | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Downloading Computer Programs | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Watching TV Programs | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Playing Games | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Reading Newspapers/Magazines | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Sending/Receiving Emails | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Social Networking Sites | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Chatting/Instant Messenger (Text) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Chatting/Instant Messenger (Voice) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Chatting/Instant Messenger (Video) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Health-Care Services | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| E-Government | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Job-Seeking Websites | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Showing Goods and Services | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| E-Banking | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Political Websites | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Hacking | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Shopping | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Visiting Adult Websites | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Sport | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Suitable Target/Target Attractiveness | Name | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective |

| Gender | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Age | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Mobile Phone Number | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Email Address | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Home Address | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Bank Account Number | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Study Program | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Credit Card Serial | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Favourite Activities | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Photos | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Videos | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Digital Guardianship | Antivirus Software | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective |

| Antispyware Software | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Firewall Software | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Ad-Aware Software | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Tracking Protection Blocks Software | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Filtering/Monitoring Software | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Changeyour Login Password | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| SaveExtra Copies | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Create a Backup Process | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Delete Old Files | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Delete Old Emails/Attachments | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Change any File Locations | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Cyberstalking victimization | Harassment | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective |

| Defamation | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Sexual Materials | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Pretending to be you | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Disable your Computer | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Monitoring your Profiles | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Sent Threatening/Offensive Letter | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

| Written Menace/Offensive Comments | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Reflective | |

The degree to which a construct’s calculation is reliable is known as reliability [59]. Internal continuity, in some terms, evaluates the interrelatedness of items. The scale’s items should have a high degree of internal accuracy. Cronbach’s coefficient alpha [60] is the most used to calculate the internal accuracy reliability coefficient, and it is concerned with the degree of interrelatedness within a group of objects constructed to measure a single construct. The higher Cronbach’s alpha is, the more reliable the intrinsic stability is. It is considered acceptable if the value is 0.70, but it is appropriate if it is 0.60 or more [61].

The final questionnaire was shown to an additional seven experts. One from UTM was a proofreader (Arabic and English). The others were the dean of the student’s college, the deputy dean, and teachers whose purposes were to increase the clarity of the instruction and wording and check the final appearance of the instrument before distributing it. Some researchers suggested that this stage was a pretest of the questionnaire, and their corrections suggested that expert suggestions were affected as well as the content validity.

4. The Theoretical Framework Concept

The tenets of routine activities and lifestyle exposure theories have been combined to create what is known as L-RAT [48][62][63]. This combination is implicit in lifestyle routine activity theories, lifestyle exposure theory, and routine activities theory used interchangeably in research such as Reyns [36]. The two separate approaches were developed in tandem and shared scientific ideas [63][64]. Although the L-RAT perspective has been applied to various physical crimes, its application to cybercrime is limited. The theoretical integration is essential in helping to explain the new crime phenomenon [65][66]. The L-RAT perspective has been one of the most tried and supported analytical models [63][67]. Cyberstalking as a new phenomenon of cybercrime has not been extensively empirically examined [32]. Only a few observational trials have been conducted, and most cyberstalking studies lack a scientific basis [68][62]. Recently, researchers have used this perspective to conduct studies about cyberstalking victimization [24]. This study proposes a conceptual model for this new phenomenon to cover the dire need for empirical assessment of cyberstalking victimization based on the L-RAT perspective. The conceptual model describes the theoretical framework and helps the reader visualize the theorized relationships [61]. The conceptual model of this study consists of four variables: proximity to motivated offenders, suitable target (target attractiveness, digital guardianship and cyberstalking victimization, moderators, and demographic/control variables).

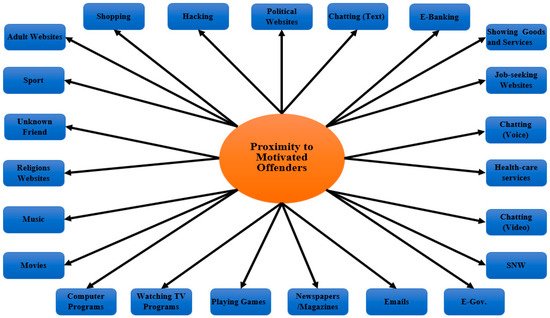

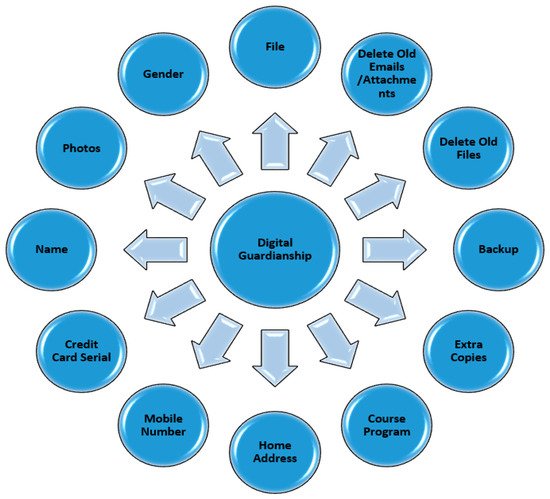

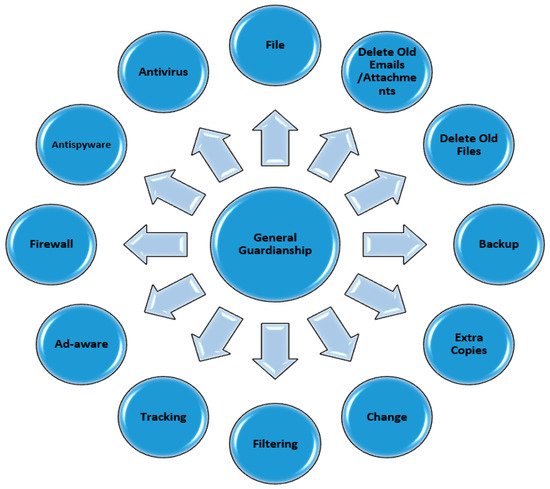

In prior studies, researchers used the term “proximity” or “exposure” interchangeably. The proximity to motivated offender variable for this study was operationalized using 23 items: hacking, political websites, e-banking, showing goods and services, job-seeking websites, e-government, health-care services, chatting/instant messenger (video), chatting/instant messenger (voice), chatting/instant messenger (text), social networking sites, sending/receiving emails, reading newspapers/magazines, playing games, watching TV programs, downloading computer programs, watching/downloading movies, listening to/downloading music, visiting religious websites, shopping, visiting adult websites, sport, adding unknown friend (see Figure 1 ). To assess the suitable target variable, 12 items were operationalized, including the victims’ personal information that was exhibited on the Internet: name, gender, age, mobile phone number, email address, home address, bank account number, study program, credit card serial, favorite activities, photos, videos (see Figure 2 ). The guardianship variable was operationalized using 12 items, including the security software installation that the victims frequently activated: antivirus software, antispyware software, firewall software, Ad-Aware software, tracking protection blocks software, filtering/monitoring software (see Figure 3 ). The information security management techniques that the victims frequently used on their computers were also included: change the login password, save extra copies from files/folders, create a backup process, delete old files, delete old emails/attachments, change any file locations.

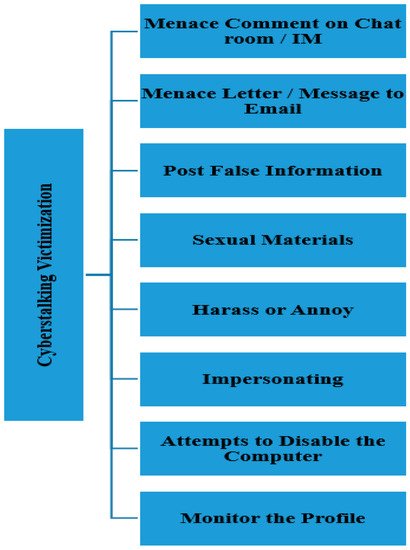

Seven control variables were assessed for this study: age (less than 18, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, others), course program (engineering, computer sciences/it, applied arts, finance and management, medical sciences, education, languages, hotel and tourism, audio and visual techniques, information management and libraries, others), academic semester (first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth semester), nationality (Jordanian, foreigner), residence (village, desert, rural, refugees, town, city, other), gender (male, female) and income (less than 500, 500–749, 750–999, 1000–1499, more than 1500 Jordan Dinars, others). The only dependent variable in the current study was operationalized using eight items by asking the victims about the online victimization behavior that they frequently faced, including being harassed or annoyed, having false information posted, being sent sexual material, someone pretending to be them, attempts to disable their computer, having their online profile monitored, being sent threatening/offensive letters or messages to their e-mail, having threatening/offensive comments made to them in chat rooms/on instant messaging sites (see Figure 4 ). A proposition is a “tentative and conjectural association between constructs”, and “hypotheses” refer to the analytical formulation of these propositions as relationships between variables [59]. With a few exceptions, comprehensive reviews of the L-RAT perspective for cyberstalking victimization lack literature. Most experiments have not operationalized any theory’s ideas (proximity to a motivated criminal, appropriate goal (target attractiveness), and digital guardianship). To account for cyberstalking victimization, this analysis thoroughly examined all of the theory’s ideas, and all hypotheses were formulated as follows:

Proximity to motivated offender has a positive effect on cyberstalking victimization.

Suitable target has a positive effect on cyberstalking victimization.

Digital guardianship harms cyberstalking victimization.

Due to the disparities between people’s diets, lifestyle sensitivity theory, which indirectly included the L-RAT viewpoint, claimed differences in victimization rates across demographic classes. Age, sex, race, marital status, wealth, education, and profession all affected people’s lifestyles [48][67]. Five moderators tested the impact of the interaction between the independent variables (proximity to driven attacker, appropriate goal (target attractiveness), and digital guardianship) and the dependent variable (cyberstalking victimization) to thoroughly assess the L-RAT and deliver/answer the study question about the demographic effects on cyberstalking victimization (cyberstalking victimization). The following are the fifteen theories that were proposed:

The relationship between proximity to motivated offenders and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by gender.

The relationship between suitable target and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by gender.

The relationship between digital guardianship and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by gender.

The relationship between proximity to motivated offenders and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by age.

The relationship between suitable target and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by age.

The relationship between digital guardianship and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by age.

The relationship between proximity to motivated offenders and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by Internet speed.

The relationship between suitable target and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by Internet speed.

The relationship between digital guardianship and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by Internet speed.

The relationship between proximity to motivated offenders and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by residence.

The relationship between suitable target and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by residence.

The relationship between digital guardianship and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by residence.

The relationship between proximity to motivated offenders and Cyberstalking victimization is moderated by nationality.

The relationship between suitable target and Cyberstalking victimization is moderated by nationality.

The relationship between digital guardianship and cyberstalking victimization is moderated by nationality.

References

- Stats, I.W. World Internet Usage and Population Statistics 2021 Year-Q1 Estimates. Available online: https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Breslin, P. An Investigation into the Problem of Cyberstalking in Ireland and an Examination of the Usefulness of Classifying Cyberstalking as an Addictive Disorder; Dublin Business School: Dublin, Ireland, 2010.

- Batra, S.; Sachdeva, S. Organizing Standardized Electronic Healthcare Records Data for Mining. Health Policy Technol. 2016, 5, 226–242.

- Broadhurst, R.; Grabosky, P.; Alazab, M.; Bouhours, B.; Chon, S. An analysis of the nature of groups engaged in cyber crime. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2014, 8, 1–20.

- Chouhan, R. Cyber crimes: Evolution, detection and future challenges. IUP J. Inf. Technol. 2014, 10, 48.

- Cox, C. Protecting victims of cyberstalking, cyberharassment, and online impersonation through prosecutions and effective laws. Jurimetrics 2014, 54, 277–302.

- Harwood, M. Security Strategies in Web Applications and Social Networking; Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 2010.

- Hensler-McGinnis, N.F. Cyberstalking Victimization: Impact and Coping Responses in a National University Sample; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2008.

- Ladan, M.J. Overview of the 2015 Legal and Policy Strategy on Cybercrime and Cybersecurity in Nigeria. SSRN Electron. J. 2015.

- Mahadevan, P. A Social Anthropology of Cybercrime, The Digitization of India’s Economic Periphery. 2020. Available online: https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/cybercrime-india/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Schell, B.J. Internet Addiction and Cybercrime. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 679–703.

- Seijen, S. Risk Perception towards Cybercrime among Students in the Netherlands: The Effect of Multiple Factors on Risk Perception; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2021.

- Sissing, S.K. A Criminological Exploration of Cyber Stalking in South Africa; University of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2013.

- Wall, D.S. The Internet as a conduit for criminal activity. Information Technology and the Criminal Justice System; Pattavina, A., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 77–98.

- Johnson, L. Computer Incident Response and Forensics Team Management: Conducting a Successful Incident Response; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013.

- Basu, S. Jones, Law, and Technology. Regul. Cyberstalking 2007, 2, 1–30.

- Bocij, P.; Griffiths, M.; McFarlane, L. Cyberstalking: A new challenge for criminal law. Crim. Lawyer 2002, 122, 3–5.

- Bocij, P. Victims of cyberstalking: An exploratory study of harassment perpetrated via the Internet. First Monday 2002, 8.

- Dhillon, G.; Smith, K.J. Defining objectives for preventing cyberstalking. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 137–158.

- Dreßing, H. Cyberstalking in a large sample of social network users: Prevalence, characteristics, and impact upon victims. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 61–67.

- Dreßing, H.; Klein, U.; Bailer, J.; Gass, P.; Gallas, C. Cyberstalking. Nervenarzt 2009, 80, 833–836.

- Easttom, C.; Taylor, J.; Hurley, H. Computer Crime, Investigation, and the Law; Course Technology: Boston, MA, USA, 2011.

- Fukuchi, A. A balance of convenience: The use of burden-shifting devices in criminal cyberharassment law. BCL Rev. 2011, 52, 289.

- Heinrich, P.A. Generation iStalk: An Examination of the Prior Relationship between Victims of Stalking and Offenders; Theses, Dissertations and Capstones; Marshall University: Huntington, WV, USA, 2015.

- Henson, B. Fear of Crime Online: Examining the Effects of Online Victimization and Perceived Risk on Fear of Cyberstalking Victimization; University of Cincinnati: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2011.

- Henson, B.; Reyns, B.; Fisher, B. Internet crime. In Key Issues in Crime and Punishment: Crime and Criminal Behavior; Chambliss, W., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011.

- Leong, N.; Morando, J.J. Communication in cyberspace. NCL Rev. 2015, 94, 105.

- Yang, Y.; Lutes, J.; Li, F.; Luo, B.; Liu, P. Stalking online: On user privacy in social networks. In Proceedings of the Second ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, New York, NY, USA, 7–9 February 2012.

- Lowry, P.B. Understanding and Predicting Cyberstalking in Social Media: Integrating Theoretical Perspectives on Shame, Neutralization, Self-Control, Rational Choice, and Social Learning. In Proceedings of the Journal of the Association for Information Systems Theory Development Workshop at the 2013 International Conference on Systems Sciences (ICIS 2013), Milan, Italy, 15–18 December 2013.

- Maple, C.; Short, E.; Brown, A. Cyberstalking in the United Kingdom: An Analysis of the ECHO Pilot Survey; University of Bedfordshire: Luton, UK, 2011.

- Mullen, P.E.; Pathé, M.; Purcell, R. Stalkers and their Victims; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009.

- Nobles, M.R.; Reyns, B.W.; Fox, K.A.; Fisher, B.S. Protection against pursuit: A conceptual and empirical comparison of cyberstalking and stalking victimization among a national sample. Justice Q. 2014, 31, 986–1014.

- Payne, B.K. Defining Cybercrime. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–25.

- Petrocelli, J.J.L.; Deerfield, O.-W.T. Cyberstalking Presenting a new challenge to law enforcement, cyberstalking occurs when electronic technology is utilized to create a criminal level of intimidation, harassment, or fear. Law Order 2005, 53, 56.

- Spitzberg, B.H.; Hoobler, G. Cyberstalking and the technologies of interpersonal terrorism. New Media Soc. 2002, 4, 71–92.

- Reyns, B.W. A Situational crime prevention approach to cyberstalking victimization: Preventive tactics for Internet users and online place managers. Crime Prev. Commun. Safety 2010, 12, 99–118.

- Yucedal, B. Victimization in Cyberspace: An Application of Routine Activity and Lifestyle Exposure Theories; Kent State University: Kent, OH, USA, 2010.

- Shorey, R.C.; Cornelius, T.L.; Strauss, C. Stalking in college student dating relationships: A descriptive investigation. J. Fam. Violence 2015, 30, 935–942.

- Elizondo, P.; McNiel, D.E.; Binder, R. A Review of Statutes and the Role of the Forensic Psychiatrist in Cyberstalking Involving Youth. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2019, 47, 198–207.

- Jaishankar, K.; Sankary, V. Cyber Stalking: A Global Menace in the Information Super Highway. ERCES Online Q. Rev. 2005, 2.

- Kaplan, B. Evaluating Health Care Information Systems: Methods and Applications; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1994.

- Kethineni, S. Cybercrime in India: Laws, Regulations, and Enforcement Mechanisms. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 305–326.

- Vasiu, I.; Vasiu, L. Cyberstalking Nature and response recommendations. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2013, 2, 229.

- Reyns, B.W.; Henson, B.; Fisher, B. Stalking in the twilight zone: Extent of cyberstalking victimization and offending among college students. Deviant Behav. 2012, 33, 1–25.

- Cuenca-Piqueras, C.; Fernández-Prados, J.S.; González-Moreno, M.J. Face-to-face versus online harassment of European women: Importance of date and place of birth. Sex. Cult. 2020, 24, 157–173.

- Curtis, L.F. Virtual vs. Reality: An Examination of the Nature of Stalking and Cyberstalking; Citeseer: 2012. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.467.5711&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Paullet, K.L. An Exploratory Study of Cyberstalking: Students and Law Enforcement in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania; Robert Morris University: Moon Twp, PA, USA, 2009.

- Gialopsos, B.M.; Carter, J.W. Offender searches and crime events. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2015, 31, 53–70.

- Stansberry, K.; Anderson, J.; Rainie, L. Experts Optimistic About the Next 50 Years of Digital Life. 2019. Available online: https://www.newswise.com/articles/experts-optimistic-about-the-next-50-years-of-digital-life (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Gálik, S.; Galikova Tolnaiova, S. Cyberspace as a new existential dimension of man. In Cyberspace; Intech Open: London, UK, 2020; pp. 13–25.

- Jahankhani, H.; Al-Nemrat, A.; Hosseinian-Far, A. Cybercrime classification and characteristics. In Cyber Crime and Cyber Terrorism Investigator’s Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 149–164.

- Tolnaiová, S.G.; Gálik, S. Cyberspace as a New Living World and Its Axiological Contexts. In Cyberspace; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020.

- (TRC), J.T.R.C. Annual Report of 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/publications/economic-and-financial-reports/annual-reports/annual-report-2015 (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Faqir, R.S. Cyber Crimes in Jordan: A Legal Assessment on the Effectiveness of Information System Crimes Law No (30) of 2010. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2013, 7, 81–90.

- Wiersma, W. Research Methods in Education: An Introduction; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1985.

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 2, 105.

- Bamasoud, D.M.; Iahad, N.A.; Rahman, A.A. Academic researchers’ absorptive capacity influence on collaborative technologies acceptance for research purpose: Pilot study. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2014, 8, 161.

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016.

- Bhattacherjee, A. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices; Global Text Project: Athens, GA, USA, 2012.

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334.

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016.

- Reyns, B.W.; Henson, B.; Fisher, B.S. Being pursued online: Applying cyberlifestyle–routine activities theory to cyberstalking victimization. Crim. Justice Behav. 2011, 38, 1149–1169.

- Reyns, B.W.; Henson, B. The thief with a thousand faces and the victim with none: Identifying determinants for online identity theft victimization with routine activity theory. Int. J. offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2016, 60, 1119–1139.

- Garofalo, J. Reassessing the Lifestyle Model of Criminal Victimization; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987; pp. 23–42.

- Back, S. Empirical Assessment of Cyber Harassment Victimization via Cyber-Routine Activities Theory. Master’s Theses, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA, 2016.

- Phillips, E. Empirical Assessment of Lifestyle-Routine Activity and Social Learning Theory on Cybercrime Offending. Master’s Theses, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA, 2015.

- McNeeley, S. Lifestyle-Routine Activities and Crime Events. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2015, 31, 30–52.

- Bossler, A.M.; Holt, D.J. On-line activities, guardianship, and malware infection: An examination of routine activities theory. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2009, 3, 400–420.