| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | J. Kelly Smith | + 1262 word(s) | 1262 | 2020-07-03 10:41:00 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1262 | 2020-07-14 08:57:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

This article details the critical roles that insulin-like growth factor-1 and its receptor insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (GFR1) play in maintaining bone homeostasis and how exposure of bone cells to microgravity affects the function of these growth factors.

1. Introduction

All terrestrial forms of life have had millions of years to adapt to Earth’s gravity (9.8 m/sec2). Cytoskeletons constructed with actin, microfilaments and microtubules resist compressive forces and allow internal load bearing [1]. Adhesive molecules such as integrins deal with external compressive forces and allow cells to maintain their positions in space [2]. Mechanosensors shuttling between cytoplasmic membranes and nuclei and matrix clusters of cell extension kinases keep the cell informed of needed changes in gene expression [3][4]. Gravisensing organelles inform roots and stems which direction in space they should occupy [5]. And cells use thermal convection in which heated fluids rise to the top of the gravity vector and are then exchanged by cooler fluids, establishing a convection current that dissipates heat, renews nutrient supplies, and removes waste materials [6].

Nature is the ultimate architect and has done well by its creatures on Earth. But man has thrown nature a curve ball and ventured into space where all these adaptations are obsolete.

The adverse effects of microgravity are particularly severe on the musculoskeletal system, particularly bone. Astronauts at are risk of losing 1.0–1.5% of their bone mass for every month they spend in space despite their adherence to high impact exercise training programs, and diets high in nutrients, potassium, calcium, and vitamin D, all designed to preserve the skeletal system. And the adverse effects of space travel on the skeletal system may persist for years after returning to Earth.

In this review, I detail the effects of microgravity on bone homeostasis and review the prominent roles that insulin-like growth factor-1 and its receptor, IGF-1R, play in the growth and maintenance this vital tissue.

2. IGF-1 and Bone Homeostasis

IGF-1 is the most abundant growth factor in bone matrix [7] where it is synthesized by osteoblast mesenchymal precursors, mature osteoblasts, osteoclasts and osteocytes [8][9]. Osteoblasts also produce all the IGFBPs [9]. Hepatocyte synthesized IGF-1 is distributed to the matrix via the bone’s nutrient and periosteal arteries located within the Volkmann and Haversian canals.

In bone, IGF-1 regulates periosteal bone expansion (radial bone growth) by its effects on osteoprogenitors at the periosteal or endocortical bone surfaces. Linear bone growth is controlled by growth hormone which stimulates chondrocyte precursors to produce IGF-1 which then acts in an autocrine fashion to induce the production of type II collagen1a via activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 pathway. With progression of chondrocytes to terminal differentiation, IGF1R signaling is terminated [10][11][12]. IGF-1 regulates bone mass by activation of mTOR in mesenchymal stem cell progenitors of osteoblasts [11].

IGF-1 has pro-differentiating and pro-survival effects on osteoblasts and their mesenchymal precursors and is essential for the anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone (PTH) on bone [12]. Activation osteoblast IGF1R initiates the expression of the runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) which stimulates the transition of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoprogenitors. Downstream of Runx2 is osterix (osx) which controls the maturation of osteoprogenitors into mature osteoblasts. Osteoblasts are responsible for the production and secretion of the extracellular matrix and expresses genes involved in matrix calcification [9].

Osteoclasts differentiate from mononuclear progenitors in the presence of macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and RANKL. Wang and associates found that mRNA expression of RANKL, RANK, and M-CSF was diminished by 35–60% in IGF-1 knockout mice and led to a reduction in osteoclastogenesis [13]; the results confirm the importance of IGF-1 in promoting osteoclast differentiation from hematologic stem cell precursors.

3. IGF-1 and Mechanical Loading

In vitro experiments of cultured MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-line cells have shown that mechanical loading generated by interstitial fluid shear stress protects osteoblasts from tumor necrosis factor-α -mediated apoptosis [15] and that the protection is mediated by flow-enhanced IGF-1-rceptor signaling [16]. Osteoblast deletion of IGF-1 or IGF1R abates the osteogenic response to mechanical loading whereas transgenic overexpression of IGF-1 in osteoblasts results in an enhanced responsiveness to in vivo mechanical loading in mice [17].

4. IGF-1 and Mechanical Unloading

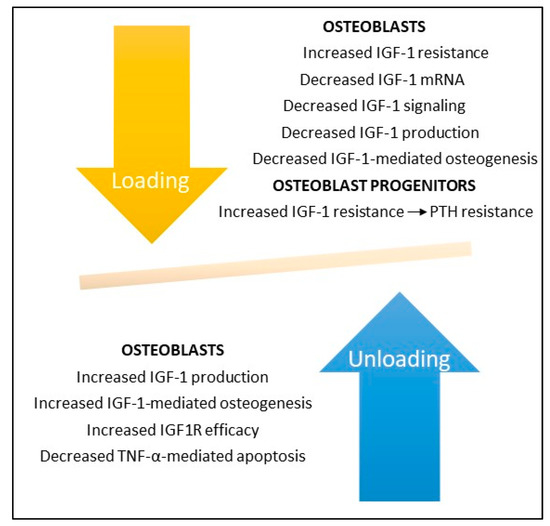

Studies during spaceflight and in bone unloading experiments on Earth have shown that bone unloading suppresses IGF-1 production (see Figure 1). Kumei et al. found that spaceflight decreased mRNA levels of IGF-1 in cultures of rat osteoblasts as compared to ground controls; they also found that microgravity completely suppressed mRNA expression of the insulin receptor substrate-1, a post-receptor signaling molecule of IGF-1 [18]. Sakata and associates found that skeletal unloading induces resistance to IGF-1 by inhibiting the activation of IGF-signaling pathways including the expression of alphaVbeta3 integrin [19]. And Triplett et al. found that mechanical loading by fluid shear stress enhanced IGF-1R signaling in osteoblasts whereas mechanical unloading inhibited its signaling [16]. Kostenuik and associates found that skeletal unloading caused resistance of osteoprogenitor cells to parathyroid hormone due to the development of resistance to IGF-1 [12].

Figure 1. Bone loading and unloading experiments demonstrate the key role IGF-1 and its receptor IGF1R play in bone formation. Bone unloading increases IGF-1 resistance and decreases IGF-1 production, signaling, and IGF-1-mediated bone formation by osteoblasts and enhances IGF-1 and PTH resistance in osteoblast mesenchymal stem cell precursors. In contrast, bone loading increases IGF-1 production and IGF1R efficiency and decreases TNF-α-mediated apoptosis in osteoblasts. Deletion of IGF-1 or IGF1R in rodents abrogates osteoblast responses to bone loading and unloading (not shown).

Hind limb suspension in rats has been shown to inhibit IGF1R signaling pathways with consequent reduction in the number and differentiation of osteoblast progenitors and reduced bone formation; responsiveness to IGF1R could be restored with reloading [19][20]. In contrast, unloading of IGF-1R knockout mice caused a permanent loss of bone synthesis, indicating that IGF1 signaling is necessary for bone formation following disuse or zero gravity [8][14].

5. Conclusions

-

By tradition bone formation is divided into four phases: 1. Osteoclast differentiation; 2. Osteoclast-mediated bone resorption; 3. Osteoblast-mediated bone formation/mineralization; and 4. Osteoblast to osteocyte transformation and establishment of bone homeostasis.

-

Zero and modeled microgravity adversely affect all four phases of bone formation, increasing the maturation and the resorptive activities of osteoclasts, decreasing the differentiation, maturation, and bone forming abilities of osteoblasts, and causing apoptotic-mediated death of osteocytes with consequent dysregulation of bone homeostasis.

-

Microgravity-associated changes in osteoblast microstructure include extended cell shapes, fragmented and condensed nuclei, shortened microtubules, smaller and fewer focal adhesions, and even complete collapse of the cytoskeleton due to microfilament and/or microtubular failure. Osteocyte death is reflected by increases in lacunar vacancies and volumes and in the production of sclerostin, a mechanosensitive protein that inhibits bone formation and enhances bone resorption.

-

IGF-1 and its receptor IGF1R play critical roles in all phases of bone formation, promoting both radial and linear bone growth. Osteocyte and osteoblast responses to mechanostressors is IGF-1/IGF1R dependent and deletion of IGF-1 or IGF1R genes abates their responses to mechanical unloading and reloading. Treatment with recombinant IGF-1 (rIGF1) reverses these defects when IGF1R is intact, raising the prospect that rIGF-1 may prove useful in preventing bone loss associated with space travel or, more likely, in the microgravity of the Moon. Another potential candidate to prevent bone loss in space or on the Moon is romosozumab, a humanized antibody against sclerostin which has been approved by the FDA for treatment of osteoporosis.

References

- Svitkina, T. The actin cytoskeleton and actin-based motility. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a018267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFlamme, S.E.; Mathew-Steiner, S.; Singh, N.; Colello-Borges, D.; Nieves, B. Integrin and microtubule crosstalk in the regulation of cellular processes. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 4177–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, B. Chain reaction: LINC complexes and nuclear positioning. F1000Research 2019, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, P.T.; Navajas, P.L.; Lietha, D. FAK Structure and regulation by membrane interactions and force in focal adhesions. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bérut, A.; Chauvet, H.; Legué, V.; Moulia, B.; Pouliquen, O.; Forterre, Y. Gravisensors in plant cells behave like an active granular liquid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5123–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.; Scheiner, A.; Cunningham, J.; Gatenby, R. Cytoplasmic convection currents and intracellular temperature gradients. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, D.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, O.; Wang, T. Visualization of ligand-bound ectodomain assembly in the full-length human IGF-1 receptor by cryo-EM single-particle analysis. Structure 2020, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakar, S.; Rosen, C.J.; Beamer, W.G.; Ackert-Bicknell, C.L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.-L.; Ooi, G.T.; Setser, J.; Frystyk, J.; Boisclair, Y.R.; et al. Circulating levels of IGF-1 directly regulate bone growth and density. J. Clin. Invest. 2002, 110, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.L.; Cao, X. Function of matrix IGF-1 in coupling bone resorption and formation. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 92, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarmatori, S.; Kiepe, D.; Haarmann, A.; Huegel, U.; Tonshoff, B. Signaling mechanisms leading to regulation of proliferation and differentiation of the mesenchymal chondrogenic cell line. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007, 38, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, L.; Wu, X.; Pang, L.; Lou, M.; Rosen, C.; Qiu, T.; Crane, J.; Frassica, F.; Zhang, L.; Rodriguez, J.P.; et al. Matrix IGF-1 regulates bone mass by activation of mTOR in mesenchymal stem cells. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenuik, P.J.; Harris, J.; Halloran, B.P.; Turner, R.T.; Morey-Holton, E.R.; Bikle, D.D. Skeletal unloading causes resistance of osteoprogenitor cells to parathyroid hormone and to insulin-like growth factor-1. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1999, 14, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nishida, S.; Elalieh, H.Z.; Long, R.K.; Halloran, B.P.; Bikle, D.D. Role of IGF-1 signaling in regulating osteoclastogenesis. J. Bone Min. Res. 2006, 21, 1350–1358.

- Yakar, S.; Werner, H.; Rosen, C.J. Insulin-like growth factors: Actions on the skeleton. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 61, T115–T137.

- Pavalko, F.M.; Gerard, R.L.; Ponik, S.M.; Gallagher, P.J.; Jin, Y.; Norvell, S.M. Fluid shear stress inhibits TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in osteoblasts: A role for fluid shear stress-induced activation of PI3-kinase and inhibition of caspase-3. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 194, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, J.W.; O’Riley, R.; Tekulve, K.; Norvell, S.M.; Pavalko, F.M. Mechanical loading by fluid shear stress enhances IGF-1 receptor signaling in osteoblasts in a PKCzeta-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biomech. 2007, 4, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tian, F.; Wang, Y.; Bickle, D.D. IGF-1 signaling mediated cell-specific skeletal mechano-transduction. J. Orthop. Res. 2018, 36, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumei, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Morita, S.; Akiyama, H.; Hirano, M.; Ohya, K.; Shinomiya, K.I.; Shimokawa, H. Space flight and insulin-like growth factor signaling in rat osteoblasts. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 973, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakata, T.; Wang, Y.; Halloran, B.P.; Elalieh, H.Z.; Cao, J.; Bikle, D.D. Skeletal unloading induces resistance to insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) by inhibiting activation of the IGF-1 signaling pathways. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Moriwake, T.; Matsuoka, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Seino, Y. Potential role of rhIGF-1/IGFBP-3 in maintaining skeletal mass in space. Bone 1998, 22, 145S–147S.