| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jeffersson Krishan Trigo-Gutierrez | + 7032 word(s) | 7032 | 2021-07-09 05:10:41 | | | |

| 2 | Lily Guo | -1 word(s) | 7031 | 2021-07-23 03:09:31 | | |

Video Upload Options

Curcumin (CUR) is a natural substance extracted from turmeric that has antimicrobial properties. Due to its ability to absorb light in the blue spectrum, CUR is also used as a photosensitizer (PS) in antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy (aPDT).

1. Introduction

2. Free CUR

| Solvent | Microorganism | Culture | Antimicrobial Method | CUR Concentration |

Light/Ultrasonic Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO (0.4%) | ZIKV | Cell infection | IC50 | 5.62–16.57 µM | - | [19] |

| >DGEV | >IC90 | |||||

| N/R | HPVA | Cell infection | Viral survival | 0.015 mg/mL | - | [20] |

| Tulane V | ||||||

| N/R | KSPV | Infected cells | EC50 | Up to 6.68 µM | - | [21] |

| Aqueous Piper nigrum seed extract | SARS-CoV-2 | Cell infection | IC50 Plaque reduction | 0.4 µg/mL | - | [22] |

| DMSO (<0.4%) | SARS-CoV-1 | Cell infection | Inhibiton of viral replication | 20 µM | - | [23] |

| N/R | SARS-CoV | In vitro | Viral inhibition | 23.5 µM | - | [24] |

| N/R | SARS-CoV | In vitro | papain-like inhibition | 5.7 µM | - | [25] |

| DMSO (1 w/v) | S. aureus | Planktonic | Inhibition zone MIC | 600 and | - | [26] |

| E. coli | 400 µg/mL | |||||

| DMSO | MRSA | Planktonic | MIC FICI |

15.5 µg/mL | - | [27] |

| N/R | S. aureus | Planktonic | Colony count | 100 µg/mL | 8 or 20 J/cm2 | [28] |

| MSSA | ||||||

| MRSA | ||||||

| DMSO (10%) | S. aureus | Biofilm | aPDT | 20, 40, and 80 µM | 5.28 J/cm2 | [29] |

| DMSO | VRSA | Biofilm/animal infection model | MIC MBC |

156.25 µg/mL | 20 J/cm2 | [30] |

| N/R | S. aureus | Animal infection model | aPDT | 78 µg/mL | 60 J/cm2 | [31] |

| DMSO | S. aureus | Infected fruit | Survival fraction | 100 nM | 1.5 and 9 J/cm2 | [32] |

| N/R | S. aureus | Planktonic | PDI | 40 and 80 µM | 15 J/cm2 | [33] |

| E. coli | ||||||

| Tween 80 (0.5%) | S. aureus | Planktonic | CFU/mL | 300 and 500 µM | 0.03–0.05 W/cm2 | [34] |

| N/R | S. aureus | Biofilm | Confocal microscope | N/R | 170 µmol m2 s1 | [35] |

| DMSO (0.5%) | S. aureus | Biofilm | SDT aPDT SPDT |

80 µM | 100 Hz 15 and 70 J/cm2 100 Hz, 15 and 70 J/cm2 |

[36] |

| DMSO | E. coli | Planktonic | MIC Inhibition zone |

110, 220 and 330 µg/mL | - | [37] |

| DMSO | E. coli | Planktonic | OD600nm | 8,16, 32, and 64 µg/mL | - | [38] |

| N/R | S. dysenteriae | Planktonic | MIC/MBC | 256 and | - | [39] |

| C. jejuni | 512 µg/mL | |||||

| Edible alcohol | E. coli | Planktonic | aPDT | 5, 10, and 20 µM | 3.6 J/cm2 | [40] |

| DMSO | H. pylori | Planktonic biofilm | MIC MBC aPDT |

50 µg/mL | 10 mW/cm2 | [41] |

| DMSO | P. aeruginosa | Biofilm | aPDT CFU/mL |

N/R | 5 and 10 J/cm2 | [42] |

| DMSO | Imipenem-resistant A. baumannii |

Planktonic | aPDT | 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM | 5.4 J/cm2 | [43] |

| DMSO (2%) | P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, E. faecalis | Planktonic | MIC/FICI | 128-256 µg/mL | - | [44] |

| N/R | C. difficile, C. sticklandii, B. fragilis, P. bryantii | Planktonic | Viable cell number | 10 µg/mL | - | [45] |

| N/R | B. subtillis, E. coli, S. carnosus, M. smegmatis | Planktonic | MIC/MBC | Up to 25 µM | - | [46] |

| N/R | MRSA | Planktonic/animal infection model | MIC | 4–16 μg/mL | - | [47] |

| MSSA | 2–8 μg/mL | |||||

| E. coli | 8–32 μg/mL | |||||

| N/R | E. faecalis, S. aureus, B. subtillis, P. aeruginosa, E. coli | Planktonic | MIC | 156 μg/mL | - | [48] |

| DMSO (0.5%) | A. hydrophila, E. coli E. faecalis, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, C. albicans |

Planktonic | MIC/MBC/ FICI/aPDT |

37.5–150 µg/mL | N/C | [49] |

| N/R | E. faecalis | Infection model | CFU/mL | 1 µg/mL | - | [50] |

| Commercial solution | E. faecalis | Biofilm | aPDT | 1.5 g/mL | 20.1 J/cm2 | [51] |

| Ethanol 99% | A. hydrophila, V. parahaemolyticus | Planktonic | aPDT/SDT | Up to 15 mg/L | N/C | [52] |

| DMSO (10%) | E. faecalis | Biofilm | MIC/MBC | 120 mg/mL | - | [53] |

| N/R | S. mutans | Planktonic | aPDT | 10 g/100cc | N/C | [54] |

| DMSO: ethyl alcohol | S. mutans, S. pyogenes | Planktonic | aPDT | 3 mg/mL | 28.8 J/cm2 | [55] |

| DMSO (0.8%) | Caries isolated | Biofilm | aPDT | 600 µg/mL | 75 J/cm2 | [56] |

| DMSO | S. mutans, C. albicans | Biofilm single/dual | MBEC | 0.5 mM | - | [57] |

| DMSO (0.05 M) | A. actinomycetemcomitans | Planktonic | aPDT | 40 µg/mL | 300–420 J/cm2 | [58] |

| DMSO (<1%) | P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans | Planktonic | aPDT | 20 µg/mL | 6, 12 or 18 J/cm2 | [59] |

| DMSO (0.5%) | P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, C. rectus, E. corrodens, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, P. micra, T. denticola, T. forsythis | Biofilm | aPDT | 100 mg/L | - | [60] |

| N/R | Subgingival plaque | Biofilm | aPDT | 100 µg/mL | 30 J/cm2 | [61] |

| DMSO | P. gingivalis | Planktonic | MIC | 12.5 µg/mL | - | [62] |

| Ethanol: DMSO (99.9%: 0.1%) |

Periodontal pocket | - | aPDT | 100 mg/mL | 7.69 J/cm2 | [63] |

| Tween 80 | Streptococcus spp, Staphylococcus spp, Enterobacteriaceae, C. albicans | Clinical trail | aPDT | 0.75 mg/mL | 20.1 J/cm2 | [64] |

| Sodium hydroxide: PBS | C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C.dubliniensis | Planktonic/biofilm | MIC | 0.1–0.5 mg/mL | - | [65] |

| N/R | C. albicans, S. aureus | Planktonic Biofilm |

MIC/Biofilm percentag | 200 µg/mL | - | [66] |

| N/R | C. albicans | Biofilm | aPDT | 1.5 g/mL | 20.1 J/cm2 | [67] |

| DMSO (10%) | C. albicans | Biofilm | aPDT | 20, 40, 60 and 80 µM | 2.64, 5.28, 7.92, 10.56, and 13.2 J/cm2 | [68] |

| DMSO (1%) | C. albicans | Biofilm | aPDT | 40 and 80 mM | 37.5 and 50 J/cm2 | [69] |

| N/R | C. albicans | Biofilm | aPDT | 100 µM | 10 J/cm2 | [70] |

| DMSO (2.5%) | Fluconazole-resistant C. albicans | Planktonic/biofilm/infection model | MIC/ aPDT |

40 µM | 5.28 J/cm2 | [71] |

| Fluconazole-susceptible C. albicans | 80 µM | 40.3 J/cm2 | ||||

| DMSO | C. albicans, F. oxysporum, A. flavus, A. niger, C. neoformans | Planktonic | MIC | 137.5–200 μg/mL | - | [72] |

2.1. Antiviral Activity

The antiviral activity of CUR has been described against enveloped and non-enveloped DNA and RNA viruses, such as HIV, Zika, chikungunya, dengue, influenza, hepatitis, respiratory syncytial viruses, herpesviruses, papillomavirus, arboviruses, and, noroviruses [11][73][74]. The action mechanism of CUR involves the inhibition of viral attachmentand penetration into the host cell and interference with viral replication machinery and the host cell signaling pathways used for viral replication. Moreover, CUR works as a virucidal substance, acting on the viral envelope or proteins [11][73][74]. CUR in 0.4%vol/vol DMSO was able to inhibit several strains of the Zika virus, including those causing human epidemics, inhibiting the viral attachment to the host cell [19]. The inhibitory effect was potentiated when CUR was combined with gossypol, which is another natural product. CUR also inhibited human strains of the dengue virus [19]. The combination of CUR with heat treatment reduced the time and temperature needed for inactivating the foodborne enteric virus (hepatitis A virus and Tulane virus—a cultivable surrogate of the human norovirus) [20]. CUR was able to inhibit the lytic replication of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) as well as reduce its pathogenesis (neoangiogenesis and cell invasionof KSHV-infected mesenchymal stem cell from the periodontal ligament) [21].2.2. Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial effect of CUR has been demonstrated against Gram-positive and Gram-negative species, including strains responsible for human infections and showing antibiotic resistance [11][16][85][86]. CUR also inhibits bacterial biofilms, which are communities of cells embedded in a self-produced polymeric matrix tolerant to antimicrobial treatments [11][16][85][86]. The antibacterial mechanism of action of CUR involves damage to the cell wall or cell membrane, interference on cellular processes by targeting DNA and proteins, and inhibition of bacterial quorum sensing (communication process mediated by biochemical signals that regulate cell density and microbial behavior) [85]. Moreover, CUR affected the L-tryptophan metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) but not in Escherichia coli (Gram-negative), produced lipid peroxidation, and increased DNA fragmentation in both bacteria [26]. These results, along with the increased levels of total thiol and antioxidant capacity observed after bacterial cells were treated with CUR, suggested that oxidative stress may be the mechanism of antibacterial action of CUR [26].Therefore, these multiple targets make CUR an interesting option for antibiotic-resistant strains. CUR is effective in killing methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), which is a concerning pathogen responsible for nosocomial and community-associated infections [86]. CUR and another polyphenol, quercetin, inhibited the growth of MRSA and their combinationwas synergistic [27]. Moreover, CUR absorbs blue light (400–500 nm) and is used as anatural photosensitizer (PS) in antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy (aPDT) [87]. CUR-mediated aPDT reduced the viability of reference strain of S. aureus and clinical isolates of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) and MRSA by 4 log10, while CUR alone reduced their survival by 2 log10 [28]. The aPDT mediated by CUR in 10% DMSO reduced the biofilm viability of S. aureus and MRSA by 3 and 2 log10, respectively, and their metabolicactivity by 94% and 89%, respectively [29]. The antibiofilm activity of CUR-mediated aPDT was also observed against clinical isolates of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA),with reductions of 3.05 log10 in biofilm viability, 67.73% in biofilm biomass, and 47.94% in biofilm matrix [30]. Additionally, aPDT resulted in the eradication of VRSA in a rat model of skin infection [30]. The association of CUR-mediated aPDT with artificial skin resulted in a 4.14 log10 reduction in S. aureus from infected wounds in rats [31].2.3. Antifungal Activity

The antifungal activity of CUR has been demonstrated mostly against Candida spp. by many in vitro and few in vivo studies [90]. CUR inhibited the growth of a reference strainand a clinical isolate of C. albicans, as well as reference strains of Candida parapsilosis, Candida glabrata, and Candida dubliniensis [65]. When biofilms of both C. albicans strains were evaluated, CUR reduced only the viability of the standard strain in a concentration-dependent effect, while the antifungal fluconazole did not inhibit the viability of either strain [65]. CUR and 2-aminobenzimidazole (2-ABI) inhibited the growth and adhesion of C. albicans and S. aureus to medical-grade silicone [66]. The combination of CUR and 2-ABI enhanced the inhibition of biofilm formation and reduced the viability of 48 h-old single and dual-species biofilms [66]. The aPDT mediated by CUR reduced the survival of 14-day-old biofilm of C. albicans in bone cavities, confirmed by fluorescence spectroscopy [67]. CUR-mediated aPDT reduced the metabolic activity of biofilms of C. albicans reference strain and clinical isolates from the oral cavity of patients with HIV and lichen planus [68]. Moreover, genes related to hyphae and biofilm formation were downregulated [68]. The aPDT mediatedby CUR and another PS, Photodithazine®, also resulted in the downregulation of genes involved in adhesion and oxidative stress response in C. albicans biofilms [69]. CUR alone and CUR-mediated aPDT, combined or not with an antibody-derived killer decapeptide,reduced the metabolic activity of an 18 h biofilm of C. albicans [70]. CUR showed synergism with fluconazole and CUR-mediated aPDT inhibited the planktonic growth and reduced the biofilm viability of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans [71]. CUR-mediated aPDT also increased the survival of Galleria mellonella infected with fluconazole-susceptible C. albicans, but did not affect the survival of larvae infected with fluconazole-resistant strain [71]. A library of 2-chloroquinoline incorporated monocarbonyl curcuminoids (MACs) was synthetized and most of the MACs exhibited strong or moderate antifungal activity compared with miconazole against C. albicans, Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, and Cryptococcus neoformans [72]. To suggest a possible antifungal mechanism, a moleculardocking analysis showed that MACs had binding affinity to sterol 14α-demethylase(CYP51), leading to impaired fungal growth [72].

3. Curcumin in DDSs (Colloidal, Metal, and Hybrid Nanosystems)

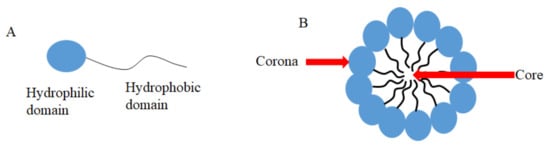

3.1. CUR in Micelles

| Type of Micelles | [CUR] Formulation | Microorganism | Type of Culture |

Antimicrobial Method | Antimicrobial [CUR] | Light/Ultrasonic Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed polymer micelles | 1000 ppm | E. coli, S. aureus, A. niger | Planktonic | MIC | 350 and 275 µg/mL | - | [92] |

| PCL-b-PAsp and Ag | 2 mg/mL | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus | Planktonic | OD600nm | 8–500 µg/mL | - | [93] |

| mPEG-OA | 1:10 | P. aeruginosa | Planktonic | MIC | 400 µg/mL | - | [94] |

| PEG-PCL | 10 mg | C. albicans | Planktonic | MIC | 256 µg/mL | - | [95] |

| PEG-PE | 50 mM | S. mutans | Planktonic | SACT | 50 mM | 1.56 W/cm2 | [96] |

| DAPMA, SPD, SPM | 0.32 mg/mL | P. aeruginosa | Planktonic | OD600nm and aPDT | 250, 500 nM, 1 µM and 50, 100 nM | 18 and 30 J/cm2 | [97] |

| P123 | 0.5% w/V | S. aureus | Planktonic | aPDT | 7.80 μmol/L | 6.5 J/cm2 | [98] |

| PCL-b-PHMG-b-PCL, STES | 10 mg | S. aureus,E. coli | Planktonic | MIC | 16 and 32 μg/mL * | - | [99] |

| CUR-PLGA-DEX | 1 mg/mL | P. fluorescens, P. putida | Planktonic biofilm | OD600nm antibiofilm | 0.625–5 mg/mL | - | [100] |

3.2. CUR in Liposomes

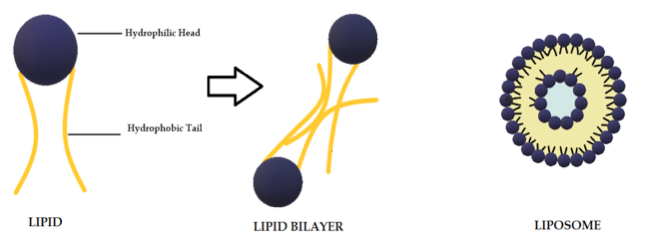

Liposomes are biodegradable and biocompatible systems, which consist of hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups (Figure 2) [101]. The hydrophobic layer is mainly composed of phospholipids and cholesterol molecules. This lipid-based carrier is suitable for administering water-insoluble drugs, such as CUR [102]. Liposomes are classified into three groups: single unilamellar vesicles, large unilamellar vesicles, and multilamellar vesicles [103]. Drugs encapsulated in liposomes are protected from chemical degradation and show increased drug solubility [101]. Additionally, liposomes have advantageous properties such as better penetration into the skin, deposition, anti-melanoma, and antimicrobial activity [102]. Antimicrobial studies with CUR-loaded liposomes are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the liposome structure.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the liposome structure.

Table 3. Antimicrobial studies performed with CUR in liposomes and solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN).

| Type of Liposomes or SLN | [CUR] Formulation | Microorganism | Type of Culture | Antimicrobial Method | Antimicrobial [CUR] | Reference |

| Lecithin and cholesterol | 0.5 mg/mL | A. sobria, C. violaceum, A. tumefaciens | Planktonic biofilm | MIC, antibiofilm | 420, 400, and 460 μg/mL | [104] |

| PCNL | 60.65 ± 1.68 µg/µl | B. subtilis, K. pneumoniae, C. violaceum, E. coli, M. smegmatis, A. niger, C. albicans, F. oxysporum | Planktonic | Disk diffusion assay | N/R | [105] |

| Phosphocolines | 100:1 M | S. aureus | Planktonic | MIC | 7 μg/mL | [106] |

| PLGA: triglycerides: F68 | 0.8 mg/mL | E. coli, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, B. sonorensis, B. licheniformis | Planktonic | MIC | 75 and 100 μg/mL | [107] |

| Soya lecithin and menthol | 0.5 mg/mL | MRSA | Planktonic, Biolfim | MIC, microscopy, biomass | 10 and 125 µg/mL | [108] |

| CurSLN | 60 mg/500 mg lipid | S. aureus, S. mutans, V. streptococci, L. acidophilus, E. coli, C. albicans | Planktonic | MIC, MBC | 0.09375–3 and 1.5–6 mg/mL | [109] |

[CUR]: CUR concentration. N/R: not reported.

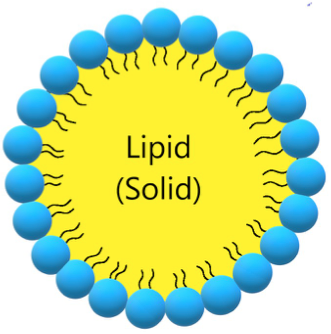

3.3. CUR in Solid Lipid Nanoparticles

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN, Figure 3, Table 3) are a modern type of lipid-based carrier composed by solid biodegradable lipids and spherical solid lipid particles. SLNs are water colloidal or aqueous surfactant solution systems [102]. SLNs have advantages such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, greater drug absorption, and drug retention [18][102], thus they are an interesting system to carry CUR [14]. Currently, SLNs have become popular because they are used as carriers for COVID-19 vaccines based on RNA vaccine technology (Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech).

Figure 3. Schematic representation of solid lipid nanoparticle.

Figure 3. Schematic representation of solid lipid nanoparticle.

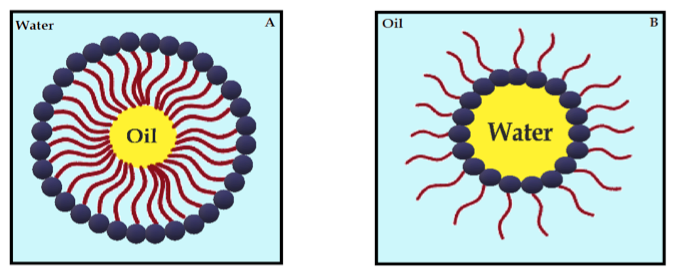

3.4. CUR in Nanoemulsions

Nanoemulsions (NE) are thermodynamically stable dispersions of oil and water (Figure 4) [110]. They are formed by a phospholipid monolayer composed of a surfactant and co-surfactant, which are important for nanoemulsion stabilization [110][111]. This system has thermodynamic stability and high solubilization characteristics, with improved drug release kinetics [112]. NE systems can be manufactured through emulsification, which can control the size of the drops and increase the drug solubility and efficacy. Moreover, the main disadvantage of NE is the high amount of surfactants in the formulation, which can lead to a potential toxic effect [111]. Antimicrobials studies with CUR-loaded NE are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of oil-in-water nanoemulsion (A) and water-in-oil nanoemulsion (B), stabilized by surfactants.

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of oil-in-water nanoemulsion (A) and water-in-oil nanoemulsion (B), stabilized by surfactants.

Table 4. Antimicrobial studies performed with curcumin/curcuminoid in emulsions.

Type ofEmulsion |

[CUR] Formulation | Microorganisms | Type of culture | Antimicrobial method | Antimicrobial Concentration | Light/Ultrasonic Paramet | Reference |

| THC ME | 5% | HIV-1 | Cell infection | IC50 | 0.9357 μM | - | [113] |

| CUR-NE | N/R | HPV | - | aPDT | 80 µM | 50 J/cm2 | [114] |

| CUR-NE | N/R | DENV-1 to 4 | Cell infection | Cell viability | 1, 5, 10 µg/mL | - | [115] |

| P60-CUR | 4 mg/L | E. coli | Planktonic | OD595 nm | N/R | - | [116] |

| PE:CUR | 0.566 mg/mL | S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. faecalis, C. albicans, E. coli | Planktonic | Inhibition zone | 1 mg/mL* | - | [117] |

| cu-SEDDS | 1% | E. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia | Planktonic | MIC | 45–62 µg/mL | - | [118] |

| CUR:NE in microbeads | 0.5 mg/mL | E. coli, S. typhmerium,Y. enterocolitica, P. aeruginosa, S, aureus, B. cereus, L. monocytogenes | Planktonic | Inhibition zone | 90 and 180 mg/mL* | - | [119] |

| Lignin sulfomethylated | 0.3 mg/mL | S. aureus | Planktonic | OD600 nm | 2.4 mg/mL* | - | [120] |

| C14-EDA/GM/WC14-MEDA/GM/W | N/R | C. albicans | Planktonic, biofilm | Microdilution assay, antibiofilm | 100 µg/mL, 20 µg | - | [121] |

[CUR]: CUR concentration. -: not performed. N/R: not reported. *: formulation concentration.

3.5. CUR in Cyclodextrin

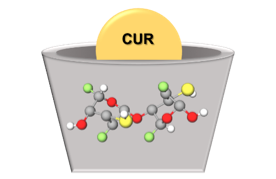

Cyclodextrins (CDs) have revolutionized the pharmaceutical industry in recent years [122]. CDs consist of three naturally occurring oligosaccharides in a cyclic structure produced from starch [123][124][125]. The natural CDs have their nomenclature system and their chemical structure based on the number of glucose residues in their structure: 6, 7, or 8 glucose units, which are denominated α-CD, β-CD, and γ-CD, respectively [126][127]. Although the entire CD molecule is soluble in water, the interior is relatively non-polar and creates a hydrophobic microenvironment. Therefore, CDs are cup-shaped, hollow structures with an outer hydrophilic layer and an internal hydrophobic cavity (Figure 5) [126]. They can sequester insoluble compounds within their hydrophobic cavity, resulting in better solubility and consequently better chemical and enzymatic stability [124]. Due to the cavity size, β-CD forms appropriate inclusion complexes with molecules with aromatic rings [128], such as CUR [129]. Antimicrobial studies with CUR in CDs are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 5. Schematic representation of CUR in CD.

Figure 5. Schematic representation of CUR in CD.

Table 5. Antimicrobial studies performed with CUR in CDs.

| Type of CD | [CUR] Formulation | Microorganism | Type of Culture | Antimicrobial Method | Antimicrobial [CUR] | Light/Ultrasonic Parameters | Reference |

| PEG-based β-CD or γ-CD | 10 µM | E. coli, E. faecalis | Planktonic | aPDT | 10 µM | 4.8, 29 J/cm2 | [130] |

| HPMC-stabilized hydroxypro pyl-β-CD | 7.64 × 10−3 M | E. coli | Planktonic | aPDT | 10, 25 µM | 5, 14, 28 J/cm2 | [131] |

| methyl-β-CD hyaluronic acid HPMC | 7.64 × 10−3 M | E. faecalis, E. coli | Planktonic | aPDT | 0.5–25 µM | 11, 16, 32 J/cm2 | [132] |

| carboxymethyl-β-CD | 20 µM | E. coli | Planktonic | aPDT | 0.7 ± 0.1 to 4.1 ± 1.6 nmole cm−2 | 1050 ± 250 lx | [133] |

| hydrogel with CUR in hydroxypropyl-β-CD | 15.8 mg/mL | S. aureus | Planktonic | Inhibition zone | 2% (w/v) | - | [134] |

| α- and β-CD | 1 mol/L | E. coli, S. aureus | Planktonic | MIC, OD600 nm | 0.25 and 0.31 mg/mL | - | [135] |

| β-CD or γ-CD in CS | 0.06 mM | E. coli, S. aureus | Planktonic | MIC, Zone of inhibition | 64 and 32 µg/mL | - | [136] |

| γ-CD | 25 mg/L | T. rubrum | Planktonic | MIC, aPDT | N/R | 45 J/cm2 | [137] |

| hydroxypropyl-β-CD | 1:1 | B. subtillis, S. aureus, S. pyrogenes, P. aeruginosa, C. difficile, C. butyricum, L. monocytogenes, E. faecalis, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, S. typhimurium, E. aerogens, C. kusei, C. albicans | Planktonic | Inhibition zone | 25 mg/mL | - | [138] |

| methyl-β-CD | 20 mM | E. coli | Planktonic | MIC, MBC, aPDT | 500, 90 µM | 9 J/cm2 | [139] |

[CUR]: CUR concentration. -: not performed. N/R: not reported.

3.6. CUR in Chitosan

Chitin is a natural polysaccharide commonly found in the exoskeleton of marine crustaceans such as shrimps, prawns, lobsters, and crabs. Chitosan (CS) derives from the acetylation of chitin and has a linear structure of D-glucosamine (deacetylated monomer) linked to N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (acetylated monomer) through β-1,4 bonds [140]. The main advantages that make CS a promising drug carrier include biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, controlled release system, mucoadhesive properties, and low cost [140][141]. Moreover, CS is soluble in aqueous solutions and is the only pseudo-natural polymer with a positive charge (cationic) [142], which can interact with negatively-charged DNA, membranes of microbial cells, and biofilm matrix [143]. Antimicrobial studies with CUR in CS are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. Antimicrobial studies performed with CUR in CS.

| Type ofCS | [CUR] Formulation | Microorganism | Type of Culture | Antimicrobial Method | Antimicrobial [CUR] | Reference |

| PEG-CS | 4.4%, 5 mg/mL | MRSA, P. aeruginosa | Planktonic, Animal model | OD600nm, CFU | 5 and 10 mg/mL * | [144] |

| CCS microspheres | 12.27 mg/mL, 1 mol | S. aureus, E. coli | Planktonic | Zone of inhibition, MIC | N/R | [145] |

| CS nanoparticles | 1.06 mg/mL | S. mutans | Planktonic, Biofilm | MIC | 0.114 mg/mL | [146] |

| CS-CMS-MMT | 0.0004–0.004 g | S. mutans | Planktonic, Biofilm | MIC | 0.101 mg/mL | [147] |

| CS-GP-CUR | 148.09 ± 5.01 µg | S. aureus | Planktonic | Zone of inhibition, tissue bacteria count | N/C | [148] |

| PVA-CS-CUR | N/C | E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, B. subtilis | Planktonic | Zone of inhibition | N/R | [149] |

| PVA-CS-CUR | 10, 20, 30 mg | P. multocida, S. aureus, E. coli, B. subtilis | Planktonic | Zone of inhibition | 10, 20, 30 mg | [150] |

| CS NPs | 2, 4, 8, 16% | C. albicans, S. aureus | Planktonic, Biofilm | MIC, Colony count | 400 mg/mL | [151] |

| CS NPs | 4 mg/mL | HCV-4 | N/R | Antiviral assay | 15 µg/mL | [152] |

| CS/milk protein nanocomposites | 100 mg | PVY | Plant infection | Antiviral activity | 500, 1000, 1500 mg/100 mL | [153] |

3.7. CUR in Other Polymeric DDS

Antimicrobial studies with CUR loaded in other polymeric DDSs are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7. Antimicrobial studies performed with curcumin in polymeric drug delivery systems.

| Type of Polymeric DDS | [CUR] Formulation | Microorganism | Type of Culture | Antimicrobial Method | Antimicrobial [CUR] | Light/Ultrasonic Parameters | Reference |

| PEG 400γ-CD and PEG + β-CD | 0.18% | E. faecalis, E. coli | Planktonic | CFU/mL aPDT | N/R | 9.7 J/cm2 29 J/cm2 | [154] |

| CUR-NP without polymer | 100 mg | S. aureus, B. subtillis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, P. notatum, A. niger | Planktonic | MIC Inhibition zone | 100 mg, 0.27 mmol | - | [155] |

| CUR-NP without polymer | 100 mg | M. lutues, S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa | Planktonic | MBC | N/R | - | [156] |

| Mixed polymer NP | 5 mM | E. coli | Planktonic | MIC | 400–500 μM | - | [157] |

| CTABTween 20Sodium dodecylsulfate | 100 mg/mL | L. monicytogenes | Planktonic | Inhibition zone | N/R | - | [158] |

| PLA/dextran sulfate | 4 mg/mL | MRSA, C. albicans, S. mutans | Planktonic/mono- and –mixed biofilm | aPDT | 260 μM | 43.2 J/cm2 | [159] |

| PLA/dextran sulfate | 0.4% | C. albicans | Animal model | aPDT | 260 μM | 37.5 J/cm2 | [160] |

| Nanocurcumin | N/R | P. aeruginosa (isolates) and standard strain | Planktonic | MIC | 128 µg/mL | - | [161] |

| PLGA | 5 mg | S. saprophyticus subsp. Bovis, E. coli | Planktonic | aPDT | 50 µg/mL | 13.2 J/cm2 | [162] |

| Eudragit L-100 | N/C | L. monocytogenes | Planktonic | Animal model infection | N/R | - | [163] |

| nCUR | N/R | S. mutans | PlanktonicBiofilm | Inhibition zoneaPDT | N/R | 300–420 J/cm2 | [164] |

| nCUR combined with indocyanine | 100 mg | E. faecalis | Biofilm | Metabolic activity | N/R | 500 mW/cm2 | [165] |

| PVAc-CUR-PET-PVDC | 0.02 g | S. aureus, S. tiphimurium | Planktonic | aPDT | N/R | 24, 48, and 72 J/cm2 | [166] |

| MOA.CUR-PLGA-NP | Up to 10% | S. mutans | Biofilm | aPDT | 7% wt | 45 J/cm2 | [167] |

| CS- β-CD | N/C | S. aureus, E. coli | Planktonic | Colony count | Up to 0.03% | - | [168] |

3.8. CUR with Metallic Nanoparticles

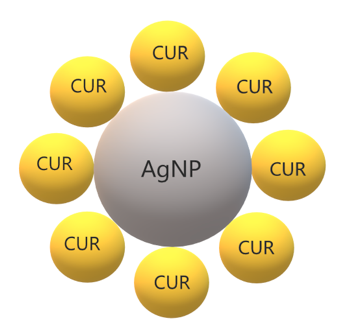

Metal complexation plays an important role in the therapeutic properties of CUR. The β-diketone moiety in the CUR chemical structure enables it to form complexes with metal ions [169]. A previous review summarized the antimicrobial activity of CUR and curcuminoid complexes with metals, such as boron, Ca2+, Cd2+, Cr3+, Co2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Ga3+, Hg2+, In3+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Pd2+, Sn2+, Y3+, and Zn2+ against viruses, bacteria, and fungi [169]. Metals have also been combined with polymers to improve the biological effects of CUR and to be used as films, hydrogels, dressings, and other pharmaceutical formulations [170][171]. In this context, silver NPs (AgNPs) have been extensively used due to their antimicrobial activity (Figure 6) [172]. Antimicrobial studies with CUR complexes with metals are summarized in Table 8.

Figure 6. Schematic representation of CUR in silver nanoparticles.

Figure 6. Schematic representation of CUR in silver nanoparticles.

Table 8. Antimicrobial studies performed with CUR complexes with metallic NPs.

| Type of Metallic Material | [CUR] Formulation | Microorganism | Type of Culture | Antimicrobial Method | Antimicrobial [CUR] | Reference |

| CUR-AgNPs | 20 mg/mL | P. aeruginosa, E. coli, B. subtilis, S. aureus | Planktonic | MIC | 20 mg/mL | [173] |

| Ag-CUR-nanoconjugates | 0.1 mM | E. coli, Salmonella spp., Fusarium spp., S. aureus | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition | 0.1 mM | [174] |

| AgCURNPs | 500 mg | P. aeruginosaS. aureus | Biofilm | CLSM SEM | Up to 400 μg/mL | [175] |

| AgNPs | 7 mg | E. coli | Planktonic | Turbidimetric Assay | 0.005 µM | [176] |

| cAgNPs | 7 mg | E. coliB. subtilis | Planktonic | MIC, CFU/mL | 7 mg | [177] |

| Ru II complex | 0.092 g | E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, Enterococcus sp. | Plakntonic | MIC/FICI | >64 µg/mL | [178] |

| SCMC SNCF nanocomposites with CUR | 0.25 mg/mL | E. coli | Planktonic | Disc Method Count Method | 2 mg/mL | [179] |

| CSCL CUR-AgNP | 0.092 g | E. coli, B. subtilis | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition | 10 and 20 μM | [180] |

| nSnH | 10% | S. aureus, E. coli. | Planktonic | CFU/mL | N/R | [181] |

| Nanocomposite of CUR and ZnO NPs | N/C | S. epidermidis, S. hemolyticus, S. saprophyticus | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition | 1000, 750, 500, 250 μg/mL | [182] |

| Thermo-responsive hydrogels | N/C | S. aureusP. aeruginosaE. coli | Planktonic | MIC | 400 μg/mL | [183] |

| CUR-AgNPs | 5 mg/mL | C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. kefyr | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition, MIC | 32.2–250 μg/mL | [184] |

| Gel-CUR-Ag | 20 mg | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus | Planktonic | MIC, MBC | 20 mg | [185] |

| HGZ-CUR | N/C | S. aureus, T. rubrum | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition | N/C | [186] |

| CHG-ZnO-CUR | N/C | S. aureus, T. rubrum | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition | N/C | [187] |

| Copper (II) oxide NPs | 1 g | E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition CFU/mL | 1 mg/mL | [188] |

| OA-Ag-C | 1 g | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus | Planktonic | OD600nm | 2.5 mg/mL | [189] |

| Ag-NP-β-CD-BC | 0.79 g | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, C. auris | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition | N/R | [190] |

| Cotton fabrics coated ZnO-NP | 2.71 × 10−3 M | S. aureus, E. coli | Planktonic | Bacterial Count | N/R | [191] |

| CS-ZnO-CUR | 0.2 g | S. aureus, E. coli | Planktonic | MIC, MBC | Up to 50 μg/mL | [192] |

| CUR-TiO2 -CS | 100–300 mg | S. aureus, E. coli | Planktonic Animal infection | MIC | 10 mg | [193] |

| CUR-Au-NPs | 1 mg/mL | E. coli, B. subtilis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa | Planktonic | Zone of Inhibition | 100, 200, 300 μg/mL | [194] |

3.9. CUR in Mesoporous Particles

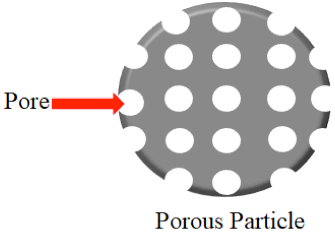

Porous materials are structures with ordered pores ranging from nanometer to micrometers, which are classified as microporous (less 2 nm), mesoporous (from 2 up to 50 nm), and macroporous (above 50 nm) [195]. Porous materials can be synthesized using carbon, silica, and metal oxides [196]. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN, Figure 7) are inorganic scaffolds [197], which seemed ideal carriers for hydrophobic drugs due to their well-defined structure, large specific surface area, and versatile chemistry for functionalization [198]. The pore size and volume and the surface area, as well as the surface functionalization of the mesoporous material, determine the drug load and release [199]. Moreover, mesoporous materials can be modified or functionalized to control drug release under environmental stimuli, such as pH, temperature, or light. These stimuli-responsive DDS, or smart DDS, prevent undesirable drug release before reaching the target tissue (“zero premature release”) [199]. Antimicrobial studies with CUR in porous DDSs are summarized in Table 9.

Figure 7. Schematic representation of a porous particle.

Figure 7. Schematic representation of a porous particle.

Table 9. Antimicrobial studies performed with CUR in porous DDSs.

| Porous DDS | [CUR] Formulation | Microorganism | Type of Culture | Antimicrobial Method | Antimicrobial [CUR] | Light/Ultrasonic Parameters | Reference |

| Cu-SNP/Ag | 1.0 mmol | E. coli | Planktonic | aPDT | N/R | 72 J/cm2 | [200] |

| Bionanocomposite silica/chitosan | 100 mg | E. coli, S. aureus | Planktonic | Zone of inhibition | N/R | - | [201] |

| NCIP | 1 mg | HIV-1 | Transfected cells | Immuno fluorescent staining | 5–8 mg/mL | - | [202] |

| Lollipop-like MSN | 30 mg L−1 | E. coli, S. aureus | Planktonic | OD600nm | N/R | - | [203] |

| SBA-15/PDA/Ag | 2 mg | E. coli, S. aureus | Planktonic | CFU/mL | 50 mM | - | [204] |

3.10. CUR in Quantum Dots

Quantum dots (QDs) are semiconductor particles at nanosize (up to 10 nm) with electrical and photoluminescence properties of biotechnological and biomedical applications, such as bioimaging and DDS [205]. Carbon dots are divided into carbon QD and graphene QD and are produced by top-down and bottom-up methods using bulk carbon material and molecular precursors, respectively [205]. Antimicrobial studies with CUR in QDs are summarized in Table 10.

Table 10. Antimicrobial studies performed with CUR in quantum dots (QDs).

| Type of Material |

[CUR] Formulation |

Microorganism | Type of Culture |

Antimicrobial Method |

Antimicrobial [CUR] |

Light/Ultrasonic Parameters |

Reference |

| CUR-cQDs | 0.6 | S. aureus MRSA E. faecalis E. coli K. pneumoniae P. aeruginosa |

Planktonic Biofilm |

Grown inhibition Biomass evaluation Confocal microscopy |

3.91– 7.825 µg/mL |

- | [206] |

| CUR-cQDs | 200 mg | EV-71 | Cell infection Animal infection |

MIC Plaque assay TC IC50 assay Western blot PCR |

5 µg/mL | - | [207] |

| CUR-MQD | 2:1 wt% | K. pneumoniae P. aeruginosa S. aureus |

Planktonic | MIC MBC Confocal microscopy Fluorescence microscopy Flow cytometry |

<0.00625– 0.125 µg/mL |

- | [208] |

| CUR-GQDs | N/C | A. actinomycetemcomitans P. gingivalis P. intermedia |

Mixed biofilm | aPDT | 100 µg/mL | 60–80 J/cm2 | [209] |

3.11. CUR in Films, Hydrogels, and Other Nanomaterials

Antimicrobial studies with CUR in films, hydrogels, and other nanomaterials are summarized in Table 11.

Table 11. Antimicrobial studies performed with CUR in films, hydrogels, and other nanomaterials.

| Type of Material | [CUR] Formulation | Microorganism | Type of Culture | Antimicrobial Method | Antimicrobial [CUR] | Light/Ultrasonic Parameters | Reference |

| CuR-SiNPs | 20 mg | S. aureus, P. aeruginosa | Planktonic, Biofilm | aPDT | 50 μg/mL, 1 mg/mL | 20 J/cm2 | [210] |

| CUR-HNT-DX | 10 mg | S. marcescens, E. coli | Planktonic, Infection model | Grown inhibition, Confocal microscopy | Up to 0.5 mg/mL | - | [211] |

| Exosomes | N/R | HIV-1 infection | - | Flow cytometry | N/R | - | [212] |

| Electrospun nanofibers | 100 mg/mL | Actinomyces naeslundii | Biofilm | aPDT | 2.5 and 5 mg/mL | 1200 mW/cm2 | [213] |

| Ga NFCD-GO NF | 0.1 mol | B. cereus, E. coli | Planktonic | Zone of inhibition, MIC | Up to 63.25 µg/mL | - | [214] |

| Multinanofibers-film | 1, 2.5, and 5 mg/mL | S. aureusE. coli | Planktonic | UFC/mL, Confocal microscopy | 1 mg/mL | - | [215] |

| Nanofibers scaffolds | 4.0 wt% | S. aureus Pseudomonassp. | Planktonic | Colony count | N/R | ,- | [216] |

| Nanofibrous scaffold | 5% | S. aureus, E. coli | Planktonic | Colony count | 20 mg | - | [217] |

| Nanofibers | 5 and 10%wt | S. aureusE. coli | Planktonic | OD600nm | Up to 212.5 µg/mL | - | [218] |

| CSDG | 1 w/w | S. aureus, E. coli | Planktonic, Infection model | Colony count, Microscopy | N/R | - | [219] |

| Gelatin film | 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 wt% | E. coli, L. monocytogenes | Planktonic | UFC/mL | 0.25 and 1.5 wt% | - | [220] |

| ZnO-CMC film | 0.5 and 1.0 wt% | E. coli, L. monocytogenes | Planktonic | UFC/mL | 1 wt% | - | [221] |

| Pectin film | 40 mg | E. coli, L. monocytogenes | Planktonic | UFC/mL | N/R | - | [222] |

| Edible film | 0.4% (w/v) | E. coli, B. subtilis | Planktonic | Zone of inhibition | 1% wt. | - | [223] |

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

CUR has a broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against viruses, bacteria, and fungi, including resistant and emergent pathogens. However, some species such as Gram-negative bacteria are less susceptible to CUR and aPDT. For those, the combination of CUR with antibiotics has been suggested, especially for antibiotic-resistant strains [220]. CUR showed synergism with polymyxin and protection against the side effects of polymyxin treatment, nephrotoxicity, and neurotoxicity [224]. Nonetheless, the evaluation of synergism requires accurate methods to study drug interaction, considering potential differences between the dose–response relationship of individual drugs and avoiding over- or under-estimation of interactions. For example, while the time–kill curve of C. jejuni treated with both cinnamon oil and ZnO NPs resulted in the over-estimation of synergism between the antimicrobials, the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) method showed no synergism but only an additive effect [225]. The FICI method was not able to detect the synergism between binary combinations of antimicrobials (cinnamon oil, ZnO NPs, and CUR encapsulated in starch) at sub-MIC, which resulted in the non-turbidity of C. jejuni. In turn, mathematical modeling using isobolograms and median-effect curves showed synergism when CUR in starch was combined with other antimicrobials against C. jejuni, with bacterial reductions of 3 log for the binary combination and over 8 log for the tertiary combination. The mathematical modeling suggested that CUR in starch was the main antimicrobial responsible for the synergistic interaction [225].

In addition to the antimicrobial evaluation, in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated the cytocompatibility and biocompatibility of CUR in DDSs [108][113][114][115][118][121][144][145][152][156][168][185][192][202][209], suggesting that CUR-loaded DDSs might be safe. Although a plethora of DDSs has been developed to circumvent the hydrophobicity, instability in solution, and low bioavailability of CUR, several studies are still performed with free CUR dissolved in organic solvents [19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][85][86][87][88][89][90]. Furthermore, compared to several in vitro investigations, few in vivo studies using animal infection models and scarce clinical trials have been reported. A randomized clinical trial showed that aPDT mediated by free CUR improved gingivitis in adolescents under fixed orthodontic treatment but did not reduce dental plaque accumulation after 1 month [226]. Clinical improvements after CUR-mediated aPDT were also observed for periodontal diseases, although few studies have evaluated the microbiological parameters [63][89]. Therefore, the improvement of clinical parameters might be due to the anti-inflammatory effect of CUR/aPDT instead of their in vivo antimicrobial activity. Nonetheless, randomized clinical trials evaluating CUR in DDSs against infections are required.

As a note on the future use of CUR, the incorporation of CUR in DDS and other pharmaceutical formulations allows its clinical use especially as an adjuvant agent to conventional antimicrobial agents. Such a combination can be an important weapon in the battle against resistant strains and emergent pathogens. The use of stimuli-responsive (or smart) DDS can also improve CUR delivery and its therapeutic effect on the target tissue. The combination of polymeric and metallic carriers may also enhance the therapeutic activity of CUR. Nonetheless, the degradation of DDS and its clearance from the body are other issues that require further investigation [18]. The evidence produced so far about the antimicrobial activity of CUR in DDSs supports future in vivo and clinical studies, which may pave the way for industrial production.

References

- Charles E Davis; Antonella Rossati; Olivia Bargiacchi; Pietro Luigi Garavelli; Anthony J McMichael; Gunnar Juliusson; Globalization, Climate Change, and Human Health. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 369, 94-96, 10.1056/nejmc1305749.

- Lance Saker; Kelley Lee; Barbara Cannito; Anna Gilmore; Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum; Globalization and infectious diseases: a review of the linkages. WHO Special Programme on Tropical Diseases Research 2004, 3, 3-12.

- Shaghayegh Gorji; Ali Gorji; COVID-19 pandemic: the possible influence of the long-term ignorance about climate change. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 15575-15579, 10.1007/s11356-020-12167-z.

- Jyoti Tanwar; Shrayanee Das; Zeeshan Fatima; Saif Hameed; Multidrug Resistance: An Emerging Crisis. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Infectious Diseases 2014, 2014, 1-7, 10.1155/2014/541340.

- Maya A. Farha; Eric D. Brown; Drug repurposing for antimicrobial discovery. Nature Microbiology 2019, 4, 565-577, 10.1038/s41564-019-0357-1.

- Bradley S. Moore; Guy T. Carter; Mark Brönstrup; Editorial: Are natural products the solution to antimicrobial resistance?. Natural Product Reports 2017, 34, 685-686, 10.1039/c7np90026k.

- Thaís Soares Bezerra Santos Nunes; Leticia Matheus Rosa; Yuliana Vega-Chacón; Ewerton Garcia De Oliveira Mima; Fungistatic Action of N-Acetylcysteine on Candida albicans Biofilms and Its Interaction with Antifungal Agents. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 980, 10.3390/microorganisms8070980.

- Susan J. Hewlings; Douglas S. Kalman; Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92, 10.3390/foods6100092.

- Subash C. Gupta; Sridevi Patchva; Bharat B. Aggarwal; Therapeutic Roles of Curcumin: Lessons Learned from Clinical Trials. The AAPS Journal 2012, 15, 195-218, 10.1208/s12248-012-9432-8.

- Mhd Anas Tomeh; Roja Hadianamrei; Xiubo Zhao; A Review of Curcumin and Its Derivatives as Anticancer Agents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 1033, 10.3390/ijms20051033.

- Michele Dei Cas; Riccardo Ghidoni; Dietary Curcumin: Correlation between Bioavailability and Health Potential. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2147, 10.3390/nu11092147.

- Kavirayani Indira Priyadarsini; The Chemistry of Curcumin: From Extraction to Therapeutic Agent. Molecules 2014, 19, 20091-20112, 10.3390/molecules191220091.

- Deljoo Somayeh; Rabiee Navid; Rabiee Mohammad; Curcumin-hybrid Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery System (Review). Asian J. Nanosci. Mater 2019, 2, 66–91, 10.26655/AJNANOMAT.2019.1.5.

- Javad Safari; Zohre Zarnegar; Advanced drug delivery systems: Nanotechnology of health design A review. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2014, 18, 85-99, 10.1016/j.jscs.2012.12.009.

- Dimas Praditya; Lisa Kirchhoff; Janina Brüning; Heni Rachmawati; Joerg Steinmann; Eike Steinmann; Anti-infective Properties of the Golden Spice Curcumin. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 912, 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00912.

- Soheil Zorofchian Moghadamtousi; Habsah Abdul Kadir; Pouya Hassandarvish; Hassan Tajik; Sazaly Abubakar; Keivan Zandi; A Review on Antibacterial, Antiviral, and Antifungal Activity of Curcumin. BioMed Research International 2014, 2014, 1-12, 10.1155/2014/186864.

- Anderson Clayton da Silva; Priscila Dayane De Freitas Santos; Jéssica Thais Do Prado Silva; Fernanda Vitória Leimann; Lívia Bracht; Odinei Hess Gonçalves; Impact of curcumin nanoformulation on its antimicrobial activity. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2018, 72, 74-82, 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.12.004.

- Simin Sharifi; Nazanin Fathi; Mohammad Yousef Memar; Seyed Mahdi Hosseiniyan Khatibi; Rovshan Khalilov; Ramin Negahdari; Sepideh Zununi Vahed; Solmaz Maleki Dizaj; Anti‐microbial activity of curcumin nanoformulations: New trends and future perspectives. Phytotherapy Research 2020, 34, 1926-1946, 10.1002/ptr.6658.

- Yaning Gao; WanBo Tai; Ning Wang; Xiang Li; Shibo Jiang; Asim K. Debnath; Lanying Du; Shizhong Chen; Gao; Tai; et al.WangLiDuChen Identification of Novel Natural Products as Effective and Broad-Spectrum Anti-Zika Virus Inhibitors. Viruses 2019, 11, 1019, 10.3390/v11111019.

- Mayuri Patwardhan; Mark T. Morgan; Vermont Dia; Doris H. D'Souza; Heat sensitization of hepatitis A virus and Tulane virus using grape seed extract, gingerol and curcumin. Food Microbiology 2020, 90, 103461, 10.1016/j.fm.2020.103461.

- He Li; Canrong Zhong; Qian Wang; Weikang Chen; Yan Yuan; Curcumin is an APE1 redox inhibitor and exhibits an antiviral activity against KSHV replication and pathogenesis. Antiviral Research 2019, 167, 98-103, 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.04.011.

- Wael H. Roshdy; Helmy A. Rashed; Ahmed Kandeil; Ahmed Mostafa; Yassmin Moatasim; Omnia Kutkat; Noura M. Abo Shama; Mokhtar R. Gomaa; Ibrahim H. El-Sayed; Nancy M. El Guindy; et al.Amal NaguibGhazi KayaliMohamed A. Ali EGYVIR: An immunomodulatory herbal extract with potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0241739, 10.1371/journal.pone.0241739.

- Chih-Chun Wen; Yueh-Hsiung Kuo; Jia-Tsrong Jan; Po-Huang Liang; Sheng-Yang Wang; Hong-Gi Liu; Ching-Kuo Lee; Shang-Tzen Chang; Chih-Jung Kuo; Shoei-Sheng Lee; et al.Chia-Chung HouPei-Wen HsiaoShih-Chang ChienLie-Fen ShyurNing-Sun Yang Specific Plant Terpenoids and Lignoids Possess Potent Antiviral Activities against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2007, 50, 4087-4095, 10.1021/jm070295s.

- Young Bae Ryu; Su-Jin Park; Young Min Kim; Ju-Yeon Lee; Woo Duck Seo; Jong Sun Chang; Ki Hun Park; Mun-Chual Rho; Woo Song Lee; SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory effects of quinone-methide triterpenes from Tripterygium regelii. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2010, 20, 1873-1876, 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.152.

- Ji-Young Park; Hyung Jae Jeong; Jang Hoon Kim; Young Min Kim; Su-Jin Park; Doman Kim; Ki Hun Park; Woo Song Lee; Young Bae Ryu; Diarylheptanoids from Alnus japonica Inhibit Papain-Like Protease of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2011, 35, 2036-2042, 10.1248/bpb.b12-00623.

- Oluyomi Stephen Adeyemi; Joy Ihuoma Obeme-Imom; Benjamin Oghenerobor Akpor; Damilare Rotimi; Gaber El-Saber Batiha; Akinyomade Owolabi; Altered redox status, DNA damage and modulation of L-tryptophan metabolism contribute to antimicrobial action of curcumin. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03495, 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03495.

- Mümtaz Güran; Gizem Şanlıtürk; Namık Refik Kerküklü; Ergül Mutlu Altundag; A. Süha Yalçın; Combined effects of quercetin and curcumin on anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial parameters in vitro. European Journal of Pharmacology 2019, 859, 172486, 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172486.

- Mirian Aa Freitas; André Hc Pereira; Juliana G Pinto; Adriana Casas; Juliana Ferreira-Strixino; Bacterial viability after antimicrobial photodynamic therapy with curcumin on multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus. Future Microbiology 2019, 14, 739-748, 10.2217/fmb-2019-0042.

- Camilo Geraldo De Souza Teixeira; Paula Volpato Sanitá; Ana Paula Dias Ribeiro; Luana Mendonça Dias; Janaina Habib Jorge; Ana Cláudia Pavarina; Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy effectiveness against susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 30, 101760, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101760.

- Farheen Akhtar; Asad U. Khan; Lama Misba; Kafil Akhtar; Asif Ali; Antimicrobial and antibiofilm photodynamic therapy against vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) induced infection in vitro and in vivo. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2021, 160, 65-76, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2021.01.012.

- Fernanda Rossi Paolillo; Phamilla Gracielli Sousa Rodrigues; Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato; Fernanda Alves; Layla Pires; Adalberto Vieira Corazza; The effect of combined curcumin-mediated photodynamic therapy and artificial skin on Staphylococcus aureus–infected wounds in rats. Lasers in Medical Science 2020, 20, 1-8, 10.1007/s10103-020-03160-6.

- Yali Li; Yi Xu; Qiaoming Liao; Mengmeng Xie; Han Tao; Hui‐Li Wang; Synergistic effect of hypocrellin B and curcumin on photodynamic inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbial Biotechnology 2021, 14, 692-707, 10.1111/1751-7915.13734.

- Thaila Quatrini Corrêa; Kate Cristina Blanco; Érica Boer Garcia; Shirly Marleny Lara Perez; Daniel José Chianfrone; Vinicius Sigari Morais; Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato; Effects of ultraviolet light and curcumin-mediated photodynamic inactivation on microbiological food safety: A study in meat and fruit. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 30, 101678, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101678.

- Truong Dang Le; Pimonpan Phasupan; Loc Thai Nguyen; Antimicrobial photodynamic efficacy of selected natural photosensitizers against food pathogens: Impacts and interrelationship of process parameters. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 32, 102024, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102024.

- Davy-Louis Versace; Gabriela Moran; Mehdi Belqat; Arnaud Spangenberg; Rachel Meallet-Renault; Samir Abbad-Andaloussi; Vlasta Brezova; Jean-Pierre Malval; Highly Virulent Bactericidal Effects of Curcumin-Based μ-Cages Fabricated by Two-Photon Polymerization. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 5050-5057, 10.1021/acsami.9b18693.

- Fernanda Alves; Gabriela Gomes Guimarães; Natália Mayumi Inada; Sebastião Pratavieira; Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato; Cristina Kurachi; Strategies to Improve the Antimicrobial Efficacy of Photodynamic, Sonodynamic, and Sonophotodynamic Therapies. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine 2021, null, 1-9, 10.1002/lsm.23383.

- Rangel-Castañeda Itzia Azucena; Cruz-Lozano José Roberto; Zermeño-Ruiz Martin; Cortes-Zarate Rafael; Hernández-Hernández Leonardo; Tapia-Pastrana Gabriela; Castillo-Romero Araceli; Drug Susceptibility Testing and Synergistic Antibacterial Activity of Curcumin with Antibiotics against Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 43, 10.3390/antibiotics8020043.

- Javier I. Sanchez-Villamil; Fernando Navarro-Garcia; Araceli Castillo-Romero; Filiberto Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez; Daniel Tapia; Gabriela Tapia-Pastrana; Curcumin Blocks Cytotoxicity of Enteroaggregative and Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by Blocking Pet and EspC Proteolytic Release From Bacterial Outer Membrane. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2019, 9, 334, 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00334.

- Sawsan Kareem; Suhad Saad Mahmood; Nada Hindi; Effects of Curcumin and Silymarin on the Shigella dysenteriae and Campylobacter jejuni In vitro. Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer 2019, 51, 824-828, 10.1007/s12029-019-00301-1.

- Yuan Gao; Juan Wu; Zhaojie Li; Xu Zhang; Na Lu; Changhu Xue; Albert Wingnang Leung; Chuanshan Xu; Qingjuan Tang; Curcumin-mediated photodynamic inactivation (PDI) against DH5α contaminated in oysters and cellular toxicological evaluation of PDI-treated oysters. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2019, 26, 244-251, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.04.002.

- Homa Darmani; Ehda A.M. Smadi; Sereen M.B. Bataineh; Blue light emitting diodes enhance the antivirulence effects of Curcumin against Helicobacter pylori. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2020, 69, 617-624, 10.1099/jmm.0.001168.

- Hayder Abdulrahman; Lama Misba; Shabbir Ahmad; Asad U. Khan; Curcumin induced photodynamic therapy mediated suppression of quorum sensing pathway of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An approach to inhibit biofilm in vitro. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 30, 101645, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.101645.

- Kai‐Chih Chang; Ya‐Yun Cheng; Meng‐Jiun Lai; Anren Hu; Identification of carbonylated proteins in a bactericidal process induced by curcumin with blue light irradiation on imipenem‐resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 2019, 34, e8548, 10.1002/rcm.8548.

- Javad Yasbolaghi Sharahi; Zahra Aliakbar Ahovan; Donya Taghizadeh Maleki; Zahra Riahi Rad; Zohreh Riahi Rad; Mehdi Goudarzi; Aref Shariati; Narjess Bostanghadiri; Elham Abbasi; Ali Hashemi; et al. In vitro antibacterial activity of curcumin-meropenem combination against extensively drug-resistant (XDR) bacteria isolated from burn wound infections.. Avicenna J Phytomed 2020, 10, 3-10.

- Jourdan E. Lakes; Christopher I. Richards; Michael D. Flythe; Inhibition of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes by select phytochemicals. Anaerobe 2020, 61, 102145-102145, 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.102145.

- Shweta Kumari; Sundarraj Jayakumar; Gagan D. Gupta; Subhash C. Bihani; Deepak Sharma; Vijay Kumar Kutala; Santosh K. Sandur; Vinay Kumar; Antibacterial activity of new structural class of semisynthetic molecule, triphenyl-phosphonium conjugated diarylheptanoid. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2019, 143, 140-145, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.08.003.

- Prince Kumar; Shamseer Kulangara Kandi; Kasturi Mukhopadhyay; Diwan S. Rawat; Gagandeep; Synthesis of novel monocarbonyl curcuminoids, evaluation of their efficacy against MRSA, including ex vivo infection model and their mechanistic studies. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 195, 112276, 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112276.

- Carlos R. Polaquini; Luana G. Morão; Ana C. Nazaré; Guilherme S. Torrezan; Guilherme Dilarri; Lúcia B. Cavalca; Débora L. Campos; Isabel Silva; Jesse Augusto Pereira; Dirk-Jan Scheffers; et al.Cristiane DuqueFernando PavanHenrique FerreiraLuis O. Regasini Antibacterial activity of 3,3′-dihydroxycurcumin (DHC) is associated with membrane perturbation. Bioorganic Chemistry 2019, 90, 103031, 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103031.

- Milena Mattes Cerveira; Helena Silveira Vianna; Edila Maria Kickhofel Ferrer; Bruno Nunes da Rosa; Claudio Martin Pereira de Pereira; Matheus Dellaméa Baldissera; Leonardo Quintana Soares Lopes; Virginia Cielo Rech; Janice Luehring Giongo; Rodrigo De Almeida Vaucher; et al. Bioprospection of novel synthetic monocurcuminoids: Antioxidant, antimicrobial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 133, 111052, 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111052.

- Michal Duracka; Norbert Lukac; Miroslava Kacaniova; Attila Kantor; Lukas Hleba; Lubomir Ondruska; Eva Tvrda; Antibiotics Versus Natural Biomolecules: The Case of In Vitro Induced Bacteriospermia by Enterococcus Faecalis in Rabbit Semen. Molecules 2019, 24, 4329, 10.3390/molecules24234329.

- Marisol Porto Rocha; Mariana Sousa Santos; Paôlla Layanna Fernandes Rodrigues; Thalita Santos Dantas Araújo; Janeide Muritiba de Oliveira; Luciano Pereira Rosa; Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato; Francine Cristina da Silva; Photodynamic therapy with curcumin in the reduction of enterococcus faecalis biofilm in bone cavity: rMicrobiological and spectral fluorescense analysis. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2021, 33, 102084, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102084.

- Shamil Rafeeq; Setareh Shiroodi; Michael H. Schwarz; Nitin Nitin; Reza Ovissipour; Inactivation of Aeromonas hydrophila and Vibrio parahaemolyticus by Curcumin-Mediated Photosensitization and Nanobubble-Ultrasonication Approaches. Foods 2020, 9, 1306, 10.3390/foods9091306.

- Sivadas Ganapathy; Shan Sainudeen; Veena S Nair; Mohammad Zarbah; Anshad Mohamed Abdulla; Chawre Mustufa Najeeb; Can herbal extracts serve as antibacterial root canal irrigating solutions? Antimicrobial efficacy of Tylophora indica, Curcumin longa, Phyllanthus amarus, and sodium hypochlorite on Enterococcus faecalis biofilms formed on tooth substrate: In vitro study. Journal of Pharmacy And Bioallied Sciences 2019, 12, 423-S429, 10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_127_20.

- Arash Azizi; Parastoo Shohrati; Mehdi Goudarzi; Shirin Lawaf; Arash Rahimi; Comparison of the effect of photodynamic therapy with curcumin and methylene Blue on streptococcus mutans bacterial colonies. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2019, 27, 203-209, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.06.002.

- Jennifer Machado Soares; Karoliny Oliveira Ozias Silva; Natalia Mayumi Inada; Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato; Kate Cristina Blanco; Optimization for microbial incorporation and efficiency of photodynamic therapy using variation on curcumin formulation. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 29, 101652, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101652.

- Daniela Alejandra Cusicanqui Méndez; Eliezer Gutierrez; Giuliana Campos Chaves Lamarque; Veridiana Lopes Rizzato; Marília Afonso Rabelo Buzalaf; Maria Aparecida Andrade Moreira Machado; Thiago Cruvinel; The effectiveness of curcumin-mediated antimicrobial photodynamic therapy depends on pre-irradiation and biofilm growth times. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2019, 27, 474-480, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.07.011.

- Xinlong Li; Luoping Yin; Gordon Ramage; Bingchun Li; Ye Tao; Qinghui Zhi; Huancai Lin; Yan Zhou; Assessing the impact of curcumin on dual‐species biofilms formed by Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans. MicrobiologyOpen 2019, 8, e937, 10.1002/mbo3.937.

- Marzie Mahdizade-Ari; Maryam Pourhajibagher; Abbas Bahador; Changes of microbial cell survival, metabolic activity, efflux capacity, and quorum sensing ability of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans due to antimicrobial photodynamic therapy-induced bystander effects. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2019, 26, 287-294, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.04.021.

- Hui Pan; Dongqing Wang; Fengqiu Zhang; In vitro antimicrobial effect of curcumin-based photodynamic therapy on Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 32, 102055, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102055.

- Sarah Böcher; Johannes-Simon Wenzler; Wolfgang Falk; Andreas Braun; Comparison of different laser-based photochemical systems for periodontal treatment. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2019, 27, 433-439, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.06.009.

- Lucas Henrique De Paula Zago; Sarah Raquel de Annunzio; Kleber Thiago de Oliveira; Paula Aboud Barbugli; Belen Retamal Valdes; Magda Feres; Carla Raquel Fontana; Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy against metronidazole-resistant dental plaque bactéria. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2020, 209, 111903, 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111903.

- Aram Mohammed Sha; Balkees Taha Garib; Aram Sha; Antibacterial Effect of Curcumin against Clinically Isolated Porphyromonas gingivalis and Connective Tissue Reactions to Curcumin Gel in the Subcutaneous Tissue of Rats.. BioMed Research International 2019, 2019, 6810936-14, 10.1155/2019/6810936.

- Camila Ayumi Ivanaga; Daniela Maria Janjacomo Miessi; Marta Aparecida Alberton Nuernberg; Marina Módolo Claudio; Valdir Gouveia Garcia; Leticia Helena Theodoro; Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) with curcumin and LED, as an enhancement to scaling and root planing in the treatment of residual pockets in diabetic patients: A randomized and controlled split-mouth clinical trial. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2019, 27, 388-395, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.07.005.

- Francine Cristina Da Silva; Luciano Pereira Rosa; Gabriel Pinto De Oliveira Santos; Natália Mayumi Inada; Kate Cristina Blanco; Thalita Santos Dantas Araújo; Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato; Total mouth photodynamic therapy mediated by blue led and curcumin in individuals with AIDS. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 2020, 18, 689-696, 10.1080/14787210.2020.1756774.

- Veena S Narayanan; Sunil Muddaiah; R Shashidara; U S Sudheendra; N C Deepthi; Lakshman Samaranayake; Variable antifungal activity of curcumin against planktonic and biofilm phase of different candida species.. Indian Journal of Dental Research 2019, 31, 145-148, 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_521_17.

- Yulong Tan; Matthias Leonhard; Doris Moser; Su Ma; Berit Schneider-Stickler; Antibiofilm efficacy of curcumin in combination with 2-aminobenzimidazole against single- and mixed-species biofilms of Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2019, 174, 28-34, 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.10.079.

- Francine Cristina da Silva; Paôlla Layanna Fernandes Rodrigues; Thalita Santos Dantas Araújo; Mariana Sousa Santos; Janeide Muritiba de Oliveira; Luciano Pereira Rosa; Gabriel Pinto De Oliveira Santos; Bruno Pereira de Araújo; Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato; Fluorescence spectroscopy of Candida albicans biofilms in bone cavities treated with photodynamic therapy using blue LED (450 nm) and curcumin. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2019, 26, 366-370, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.05.002.

- Jing Ma; Hang Shi; Hongying Sun; Jiyang Li; Yu Bai; Antifungal effect of photodynamic therapy mediated by curcumin on Candida albicans biofilms in vitro. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2019, 27, 280-287, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.06.015.

- Cláudia Carolina Jordão; Tábata Viana de Sousa; Marlise Inêz Klein; Luana Mendonça Dias; Ana Cláudia Pavarina; Juliana Cabrini Carmello; Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy reduces gene expression of Candida albicans in biofilms. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 31, 101825, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101825.

- Elisabetta Merigo; Marlène Chevalier; Stefania Conti; Tecla Ciociola; Carlo Fornaini; Maddalena Manfredi; Paolo Vescovi; Alain Doglio; Antimicrobial effect on Candida albicans biofilm by application of different wavelengths and dyes and the synthetic killer decapeptide KP. LASER THERAPY 2018, 28, 180-186, 10.5978/islsm.28_19-OR-14.

- Yuliana Vega-Chacón; Maria Carolina de Albuquerque; Ana Cláudia Pavarina; Gustavo Henrique Goldman; Ewerton Garcia De Oliveira Mima; Verapamil inhibits efflux pumps in Candida albicans, exhibits synergism with fluconazole, and increases survival of Galleria mellonella. Virulence 2020, 12, 231-243, 10.1080/21505594.2020.1868814.

- Amol A. Nagargoje; Satish Akolkar; Madiha M. Siddiqui; Dnyaneshwar D. Subhedar; Jaiprakash N. Sangshetti; Vijay M. Khedkar; Bapurao Babruwan Shingate; Quinoline Based Monocarbonyl Curcumin Analogs as Potential Antifungal and Antioxidant Agents: Synthesis, Bioevaluation and Molecular Docking Study. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2019, 17, null, 10.1002/cbdv.201900624.

- Morgan Jennings; Robin Parks; Curcumin as an Antiviral Agent. Viruses 2020, 12, 1242, 10.3390/v12111242.

- Dony Mathew; Wei-Li Hsu; Antiviral potential of curcumin. Journal of Functional Foods 2017, 40, 692-699, 10.1016/j.jff.2017.12.017.

- Divya M. Teli; Mamta B. Shah; Mahesh T. Chhabria; In silico Screening of Natural Compounds as Potential Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease and Spike RBD: Targets for COVID-19. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 7, 599079, 10.3389/fmolb.2020.599079.

- Atala B. Jena; Namrata Kanungo; Vinayak Nayak; G.B.N. Chainy; Jagneshwar Dandapat; Catechin and Curcumin interact with corona (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV2) viral S protein and ACE2 of human cell membrane: insights from Computational study and implication for intervention. Scientific Reports 2020, 11, 1-14, 10.21203/rs.3.rs-22057/v1.

- Mohit Kumar; Kushneet Kaur Sodhi; Dileep Kumar Singh; Addressing the potential role of curcumin in the prevention of COVID-19 by targeting the Nsp9 replicase protein through molecular docking. Archives of Microbiology 2021, 203, 1691-1696, 10.1007/s00203-020-02163-9.

- Ashish Patel; Malathi Rajendran; Ashish Shah; Harnisha Patel; Suresh B. Pakala; Prashanthi Karyala; Virtual screening of curcumin and its analogs against the spike surface glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2021, 5, 1-9, 10.1080/07391102.2020.1868338.

- Loubna Allam; Fatima Ghrifi; Hakmi Mohammed; Naima El Hafidi; Rachid El Jaoudi; Jaouad El Harti; Badreddine Lmimouni; Lahcen Belyamani; Azeddine Ibrahimi; Targeting the GRP78-Dependant SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry by Peptides and Small Molecules. Bioinformatics and Biology Insights 2019, 14, 1177932220965505, 10.1177/1177932220965505.

- Mahmoud A.A. Ibrahim; Alaa H.M. Abdelrahman; Taha A. Hussien; Esraa A.A. Badr; Tarik A. Mohamed; Hesham R. El-Seedi; Paul W. Pare; Thomas Efferth; Mohamed-Elamir F. Hegazy; In silico drug discovery of major metabolites from spices as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2020, 126, 104046-104046, 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104046.

- Suresh Kumar; Priya Kashyap; Suman Chowdhury; Shivani Kumar; Anil Panwar; Ashok Kumar; Identification of phytochemicals as potential therapeutic agents that binds to Nsp15 protein target of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) that are capable of inhibiting virus replication. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153317-153317, 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153317.

- Vimal K. Maurya; Swatantra Kumar; Anil K. Prasad; Madan L. B. Bhatt; Shailendra K. Saxena; Structure-based drug designing for potential antiviral activity of selected natural products from Ayurveda against SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and its cellular receptor. VirusDisease 2020, 31, 179-193, 10.1007/s13337-020-00598-8.

- Jiao Wang; Xiaoli Zhang; Alejandra B. Omarini; Binglin Li; Virtual screening for functional foods against the main protease of SARS‐CoV‐2. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2020, 44, 13481, 10.1111/jfbc.13481.

- Debmalya Barh; Sandeep Tiwari; Marianna E. Weener; Vasco Azevedo; Aristóteles Góes-Neto; M. Michael Gromiha; Preetam Ghosh; Multi-omics-based identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection biology and candidate drugs against COVID-19. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2020, 126, 104051-104051, 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104051.

- Dantong Zheng; Chongxing Huang; Haohe Huang; Yuan Zhao; Muhammad Rafi Ullah Khan; Hui Zhao; Lijie Huang; Antibacterial Mechanism of Curcumin: A Review. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2020, 17, 2000171, 10.1002/cbdv.202000171.

- Sin-Yeang Teow; Kitson Liew; Syed A. Ali; Alan Soo-Beng Khoo; Suat-Cheng Peh; Antibacterial Action of Curcumin against Staphylococcus aureus: A Brief Review. Journal of Tropical Medicine 2016, 2016, 1-10, 10.1155/2016/2853045.

- Carolina Santezi; Bárbara Donadon Reina; Lívia Nordi Dovigo; Curcumin-mediated Photodynamic Therapy for the treatment of oral infections—A review. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2018, 21, 409-415, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.01.016.

- Fernanda Alves; Ana Cláudia Pavarina; Ewerton Garcia De Oliveira Mima; Anthony P McHale; John Francis Callan; Antimicrobial sonodynamic and photodynamic therapies against Candida albicans. Biofouling 2018, 34, 357-367, 10.1080/08927014.2018.1439935.

- Fatemeh Forouzanfar; Ali Forouzanfar; Thozhukat Sathyapalan; Hossein M. Orafai; Amirhossein Sahebkar; Curcumin for the Management of Periodontal Diseases: A Review. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2020, 26, 4277-4284, 10.2174/1381612826666200513112607.

- Kourosh Cheraghipour; Behrouz Ezatpour; Leila Masoori; Abdolrazagh Marzban; Asghar Sepahvand; Arian Karimi Rouzbahani; Abbas Moridnia; Sayyad Khanizadeh; Hossein Mahmoudvand; Anti-Candida Activity of Curcumin: A Systematic Review. Current Drug Discovery Technologies 2021, 18, 379-390, 10.2174/1570163817666200518074629.

- Kazunori Kataoka; Atsushi Harada; Yukio Nagasaki; Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: design, characterization and biological significance. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2001, 47, 113-131, 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00124-1.

- Muhammad Usman Akbar; Khalid Mahmood Zia; Ahsan Nazir; Jamshed Iqbal; Syeda Abida Ejaz; Muhammad Sajid Hamid Akash; Pluronic-Based Mixed Polymeric Micelles Enhance the Therapeutic Potential of Curcumin. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19, 2719-2739, 10.1208/s12249-018-1098-9.

- Fan Huang; Yang Gao; Yumin Zhang; Tangjian Cheng; Hanlin Ou; Lijun Yang; Jinjian Liu; Linqi Shi; Jianfeng Liu; Silver-Decorated Polymeric Micelles Combined with Curcumin for Enhanced Antibacterial Activity. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017, 9, 16880-16889, 10.1021/acsami.7b03347.

- Saeid Rahbar Takrami; Najmeh Ranji; Majid Sadeghizadeh; Antibacterial effects of curcumin encapsulated in nanoparticles on clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa through downregulation of efflux pumps. Molecular Biology Reports 2019, 46, 2395-2404, 10.1007/s11033-019-04700-2.

- Fangfang Teng; Peizong Deng; Zhimei Song; Feilong Zhou; Runliang Feng; Enhanced effect in combination of curcumin- and ketoconazole-loaded methoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly (ε-caprolactone) micelles. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 88, 43-51, 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.033.

- Maryam Pourhajibaghera; BahmanRahimi esboeibc; Mahshid Hodjata; Abbas Bahadord; [Email Protected]; Sonodynamic excitation of nanomicelle curcumin for eradication of Streptococcus mutans under sonodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy: Enhanced anti-caries activity of nanomicelle curcumin. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2020, 30, 101780, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101780.

- Katia Rupel; Luisa Zupin; Silvia Brich; Mario Mardirossian; Giulia Ottaviani; Margherita Gobbo; Roberto Di Lenarda; Sabrina Pricl; Sergio Crovella; Serena Zacchigna; et al.Matteo Biasotto Antimicrobial activity of amphiphilic nanomicelles loaded with curcumin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa alone and activated by blue laser light. Journal of Biophotonics 2020, 14, null, 10.1002/jbio.202000350.

- Victor Hugo Cortez Dias; Amanda Milene Malacrida; Adriele Rodrigues dos Santos; Andreia Farias Pereira Batista; Paula Aline Zanetti Campanerut-Sá; Gustavo Braga; Evandro Bona; Wilker Caetano; Jane Martha Graton Mikcha; pH interferes in photoinhibitory activity of curcumin nanoencapsulated with pluronic® P123 against Staphylococcus aureus. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2021, 33, 102085, 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102085.

- Yanhui Zhu; Qiaojie Luo; Hongjie Zhang; Qiuquan Cai; Xiaodong Li; Zhiquan Shen; Weipu Zhu; A shear-thinning electrostatic hydrogel with antibacterial activity by nanoengineering of polyelectrolytes. Biomaterials Science 2019, 8, 1394-1404, 10.1039/c9bm01386e.

- Caio H N Barros; Dishon W Hiebner; Stephanie Fulaz; Stefania Vitale; Laura Quinn; Eoin Casey; Synthesis and self-assembly of curcumin-modified amphiphilic polymeric micelles with antibacterial activity.. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 104.

- N.P. Aditya; Geetanjali Chimote; Karthigayan Gunalan; Rinti Banerjee; Swati Patankar; Basavaraj Madhusudhan; Curcuminoids-loaded liposomes in combination with arteether protects against Plasmodium berghei infection in mice. Experimental Parasitology 2012, 131, 292-299, 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.04.010.

- Soumitra Shome; Anupam Das Talukdar; Manabendra Dutta Choudhury; Mrinal Kanti Bhattacharya; Hrishikesh Upadhyaya; Curcumin as potential therapeutic natural product: a nanobiotechnological perspective. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2016, 68, 1481-1500, 10.1111/jphp.12611.

- Yan Chen; Yao Lu; Robert J Lee; Guangya Xiang; Nano Encapsulated Curcumin: And Its Potential for Biomedical Applications. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2020, ume 15, 3099-3120, 10.2147/ijn.s210320.

- Ting Ding; Tingting Li; Zhi Wang; Jianrong Li; Curcumin liposomes interfere with quorum sensing system of Aeromonas sobria and in silico analysis. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1-16, 10.1038/s41598-017-08986-9.

- Anuj Mittal; Naveen Kumar; Nar Singh Chauhan; Curcumin Encapsulated PEGylated Nanoliposomes: A Potential Anti-Infective Therapeutic Agent. Indian Journal of Microbiology 2019, 59, 336-343, 10.1007/s12088-019-00811-3.

- Sara Battista; Maria Anna Maggi; Pierangelo Bellio; Luciano Galantini; Angelo Antonio D’Archivio; Giuseppe Celenza; Roberta Colaiezzi; Luisa Giansanti; Curcuminoids-loaded liposomes: influence of lipid composition on their physicochemical properties and efficacy as delivery systems. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 597, 124759, 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.124759.

- Mengqian Gao; Xue Long; Jing Du; Mengting Teng; Weichen Zhang; Yuting Wang; Xingqi Wang; Ziyuan Wang; Peng Zhang; Jun Li; et al. Enhanced curcumin solubility and antibacterial activity by encapsulation in PLGA oily core nanocapsules. Food & Function 2019, 11, 448-455, 10.1039/c9fo00901a.

- Eshant Bhatia; Shivam Sharma; Kiran Jadhav; Rinti Banerjee; Combinatorial liposomes of berberine and curcumin inhibit biofilm formation and intracellular methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections and associated inflammation. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2020, 9, 864-875, 10.1039/d0tb02036b.

- Heba A. Hazzah; Ragwa M. Farid; Maha M.A. Nasra; Walaa A. Hazzah; Magda A. El-Massik; Ossama Y. Abdallah; Gelucire-Based Nanoparticles for Curcumin Targeting to Oral Mucosa: Preparation, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Activity Assessment. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 104, 3913-3924, 10.1002/jps.24590.

- Min Sun; Xun Su; Buyun Ding; Xiuli He; Xiuju Liu; Aihua Yu; Hongxiang Lou; Guangxi Zhai; Advances in nanotechnology-based delivery systems for curcumin. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 1085-1100, 10.2217/nnm.12.80.

- Ankur Gupta; Huseyin Burak Eral; Trevor Alan Hatton; Patrick S. Doyle; Nanoemulsions: formation, properties and applications. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 2826-2841, 10.1039/c5sm02958a.

- Gagan Flora; Deepesh Gupta; Archana Tiwari; Nanocurcumin: A Promising Therapeutic Advancement over Native Curcumin. Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems 2012, 30, 331-368, 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.2013007236.

- Amit Mirani; Harish Kundaikar; Shilpa Velhal; Vainav Patel; Atmaram Bandivdekar; Mariam Degani; Vandana Patravale; Tetrahydrocurcumin-loaded vaginal nanomicrobicide for prophylaxis of HIV/AIDS: in silico study, formulation development, and in vitro evaluation. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2019, 9, 828-847, 10.1007/s13346-019-00633-2.

- Caroline Measso Do Bonfim; Letícia Figueiredo Monteleoni; Marília De Freitas Calmon; Natália Maria Cândido; Paola Jocelan Scarin Provazzi; Vanesca De Souza Lino; Tatiana Rabachini; Laura Sichero; Luisa Lina Villa; Silvana Maria Quintana; et al.Patrícia Pereira Dos Santos MelliFernando Lucas PrimoCamila AmantinoAntonio TedescoEnrique BoccardoPaula Rahal Antiviral activity of curcumin-nanoemulsion associated with photodynamic therapy in vulvar cell lines transducing different variants of HPV-16. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 2019, 48, 515-524, 10.1080/21691401.2020.1725023.

- Najwa Nabila; Nadia Khansa Suada; Dionisius Denis; Benediktus Yohan; Annis Catur Adi; Anna Surgean Veterini; Atsarina Larasati Anindya; R. Tedjo Sasmono; Heni Rachmawati; Antiviral Action of Curcumin Encapsulated in Nanoemulsion against Four Serotypes of Dengue Virus. Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology 2020, 8, 54-62, 10.2174/2211738507666191210163408.

- Atinderpal Kaur; Yashaswee Saxena; Rakhi Bansal; Sonal Gupta; Amit Tyagi; Rakesh Kumar Sharma; Javed Ali; Amulya Kumar Panda; Reema Gabrani; Shweta Dang; et al. Intravaginal Delivery of Polyphenon 60 and Curcumin Nanoemulsion Gel.. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 2188-2202, 10.1208/s12249-016-0652-6.

- Fahanwi Asabuwa Ngwabebhoh; Sevinc Ilkar Erdagi; Ufuk Yildiz; Pickering emulsions stabilized nanocellulosic-based nanoparticles for coumarin and curcumin nanoencapsulations: In vitro release, anticancer and antimicrobial activities. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 201, 317-328, 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.08.079.

- Momin Khan, Muhammad Ali, Walayat Shah, Akram Shah & Muhammad Masoom Yasinzai; Curcumin-loaded self-emulsifying drug delivery system (cu-SEDDS): A promising approach for the control of primary pathogen and secondary bacterial infections in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology volume 2019, 103, 7481.

- Ayat F. Hashim; Said Hamed; Hoda A. Abdel Hamid; Kamel A. Abd-Elsalam; Iwona Golonka; Witold Musiał; Ibrahim M. El-Sherbiny; Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of omega-3 rich oils/curcumin nanoemulsions loaded in chitosan and alginate-based microbeads. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 140, 682-696, 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.085.

- Kai Chen; Yong Qian; Senyi Wu; Xueqing Qiu; Dongjie Yang; Lei Lei; Neutral fabrication of UV-blocking and antioxidation lignin-stabilized high internal phase emulsion encapsulates for high efficient antibacterium of natural curcumin. Food & Function 2019, 10, 3543-3555, 10.1039/c9fo00320g.

- Agnieszka Lewińska; Anna Jaromin; Julia Jezierska; Role of architecture of N-oxide surfactants in the design of nanoemulsions for Candida skin infection. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2020, 187, 110639, 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110639.

- Jaya Lakkakula; Rui Werner Maçedo Krause; A vision for cyclodextrin nanoparticles in drug delivery systems and pharmaceutical applications. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 877-894, 10.2217/nnm.14.41.

- Fliur Macaev; Veaceslav Boldescu; Athina Geronikaki; Natalia Sucman; Recent Advances in the Use of Cyclodextrins in Antifungal Formulations. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 13, 2677-2683, 10.2174/15680266113136660194.

- Takuro Kurita; Yuji Makino; Novel curcumin oral delivery systems.. Anticancer Research 2013, 33, 2807–2821.

- E.M.Martin Del Valle; Cyclodextrins and their uses: a review. Process Biochemistry 2004, 39, 1033-1046, 10.1016/s0032-9592(03)00258-9.

- Atwood Jerry L.. Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry; Gokel George, Eds.; .: New York, USA, 1996; pp. 1.

- Phennapha Saokham; Chutimon Muankaew; Phatsawee Jansook; Thorsteinn Loftsson; Solubility of Cyclodextrins and Drug/Cyclodextrin Complexes. Molecules 2018, 23, 1161, 10.3390/molecules23051161.

- Mark E. Davis; Marcus E. Brewster; Cyclodextrin-based pharmaceutics: past, present and future. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2004, 3, 1023-1035, 10.1038/nrd1576.

- Aaron J. Smith; John Oertle; Dino Prato; Multiple Actions of Curcumin Including Anticancer, Anti-Inflammatory, Antimicrobial and Enhancement via Cyclodextrin. Journal of Cancer Therapy 2014, 06, 257-272, 10.4236/jct.2015.63029.

- Anne Bee Hegge; Thorbjørn T. Nielsen; Kim L. Larsen; Ellen Bruzell; Hanne H. Tønnesen; Impact of Curcumin Supersaturation in Antibacterial Photodynamic Therapy—Effect of Cyclodextrin Type and Amount: Studies on Curcumin and Curcuminoides XLV. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2012, 101, 1524-1537, 10.1002/jps.23046.

- Anne Bee Hegge; M. Vukicevic; E. Bruzell; S. Kristensen; H.H. Tønnesen; Solid dispersions for preparation of phototoxic supersaturated solutions for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT). European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2012, 83, 95-105, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.09.011.

- Kristine Wikene; Anne Bee Hegge; Ellen Bruzell; Hanne Hjorth Tønnesen; Formulation and characterization of lyophilized curcumin solid dispersions for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT): studies on curcumin and curcuminoids LII. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy 2014, 41, 969-977, 10.3109/03639045.2014.919315.

- Ilya Shlar; Samir Droby; Victor Rodov; Antimicrobial coatings on polyethylene terephthalate based on curcumin/cyclodextrin complex embedded in a multilayer polyelectrolyte architecture. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2018, 164, 379-387, 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.02.008.