Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barbara Farkas | + 4571 word(s) | 4571 | 2021-07-07 08:20:55 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 4571 | 2021-07-09 10:15:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Farkas, B. Modelling Metallic Magnetic Nanoparticles. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11870 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Farkas B. Modelling Metallic Magnetic Nanoparticles. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11870. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Farkas, Barbara. "Modelling Metallic Magnetic Nanoparticles" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11870 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Farkas, B. (2021, July 09). Modelling Metallic Magnetic Nanoparticles. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11870

Farkas, Barbara. "Modelling Metallic Magnetic Nanoparticles." Encyclopedia. Web. 09 July, 2021.

Copy Citation

Recent years have seen a significant growth in the use of metallic magnetic nanoparticles due to the versatile functionality which is intrinsically linked to their morphology, where both the particle size and shape contribute to the prominent magnetic features. The aim of this entry is to establish the predictive power of computational modelling in explaining these phenomena at the atomic level, allowing researches to find the link between the size, shape, and ligand-mediated property changes which will facilitate design of the tuning strategies for the realisation of application-specific magnetic behaviour at the nanoscale.

nanoparticles

density functional theory

magnetic hyperthermia

magnetic anisotropy

1. History of Use and Study of Metal Nanoparticles in Biomedicine

Metal nanoparticles (MNPs) have been attracting researchers’ attention for over a century, owing to the diversity in their properties and the unique phenomena that only exist at the nanoscale and have unlocked many new pathways to implement metals as technology materials. However, MNPs have been used, albeit unknowingly, long before modern ages. They were an integral part in the cosmetics of the ancient Egyptians, whereas the Romans were famous for their workmanship of stained glass which evolved from the absorption of light through gold and silver MNPs—the most renowned example being the Lycurgus cup. The trend of dyed glass and metal-resembling glazes on ceramic pottery continued deep into the Middle Ages before the origin of the colouring effects was linked to the presence of optically active colloidal nanosized metallic particles in 1857 by Michael Faraday. Today, efforts to unravel new tuning strategies leading to desired properties of MNPs continue to grow, and utilisation of such nanotechnology has moved a long way from stained glass, reaching an extensive range of confirmed and potential applications in catalysis [1][2][3][4], electronics [5][6][7], optics [8][9][10][11], information storage [12][13][14], and finally, medicine [15][16][17][18][19].

MNPs can exist as common single element structures, constituting alkali/alkaline, transition, or noble metals, or they can be composites of two or more different metals, known as nanoalloys. Their physical and chemical characteristics are determined not only by the chemical composition as in the respective bulk materials, but also by their size and morphology. Therefore, tailoring of the MNP properties depends on the strict control of each of these parameters. Only recently have advances in experimental equipment and methods led to the synthesis of MNPs of a uniform size distribution with directed morphology control of particles synthesised in solution, giving rise to the development of numerous production techniques. Today, procedures to generate MNPs with extensive control over their size and shape are well established, even to the point of reaching atomic-level precision in cluster and MNP synthesis, isolation, and deposition on a support [20][21]. Such progress has enabled the correlation between the MNP properties and size and shape effects, with multiple examples cited in the recent literature [22][23][24][25][26][27][28]. Nonetheless, MNPs are principally neither isolated nor clean, rather frequently stabilised by solvent or surfactant molecules or in form of particle aggregates, the presence of which makes the structural determination cumbersome. Consequently, experimental characterisation techniques still face significant challenges in assigning the influence of structural parameters on certain properties over the size distribution of the synthesised MNPs [29], and computational simulations have been shown to significantly contribute to the unravelling of size, morphology, and environmental effects on properties of individual MNPs [30][31][32][33][34].

In recent years, the emerging potential of MNPs with specific magnetic properties (called magnetic metal nanoparticles, mNPs, in the remaining text) has brought further advances in biomedicine. Their response to an externally applied magnetic field, in combination with easy conjugation of the metallic surfaces with various functional groups present in biomolecules, antibodies, and drugs of interest, has opened up a completely new range of biomedical applications, where magnetically induced preconcentration, identification, and separation are merged with targeted medical analytes in a single agent at the nanometre scale. This approach has allowed the development of drug delivery with reduced distribution of medical substances in untargeted tissues and improved contrasts in body scans through magnetic resonance imaging, whereas hyperthermia therapies have progressed from treatments increasing whole-body temperature to treatments with completely localised magnetically induced heat generation, as described in the following text. Initially, the focus was on the use of magnetic nanoparticles of biocompatible metallic oxides, mainly magnetite/maghemite, but upon the failed efforts to sufficiently improve their magnetic moments to fulfil the requirements of the therapies, naturally magnetic metallic counterparts, mNPs, have started to generate an appreciable amount of interest. Many of such mNP agents are already approved for clinical use, but the search for those with superior response and higher efficiencies at safer external field strengths continues, including less obvious material choices, such as Co mNPs, as promising candidates.

A comprehensive, although not by any means complete, summary of magnetic core NPs with protective coatings designed for biomedical purposes can be found in Table 1. There are many reviews on the role of iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine, with details behind the exhaustive efforts to adjust their properties for specific applications [35][36][37][38][39][40][41]. However, the topics of the current review are metal nanoparticles, the interplay between their physical and magnetic properties as they relate to the performance in biomedical applications, and how to approach and predict this dependence from a computational modelling perspective, focusing on the example of cobalt mNPs.

1.1. Biomedical Applications of mNPs

1.1.1. MRI

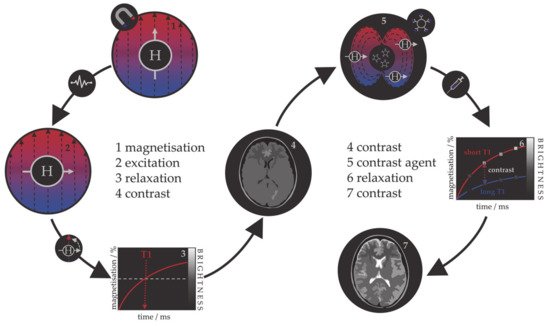

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a powerful, noninvasive, and sensitive tomographic visualisation technique widely used in biomedicine to obtain high-resolution scans of body cross-sections. An MRI image originates from the measurement of nuclear magnetic resonance (NRM) signals that are collected as responses of abundant water protons present in biological tissues to the applied magnetic field [42][43][44]. In rare cases, signals are detected from other nuclei, such as C13, P31, or Na25. A strong static magnetic field is first applied to align the magnetic moments of proton nuclei, which are then deflected in the transversal plane upon the application of a short radiofrequency pulse. Magnetic moments spontaneously return to the original longitudinal direction of the magnetic field, and the time necessary for the complete realignment is called relaxation time. One can distinguish between the T1 relaxation time corresponding to the longitudinal recovery and the T2 relaxation time of the transversal decay. Both are sources of tissue contrasts in MRI scans, which depend on the net magnetic effect of a large number of nuclei within a specific voxel of tissue. Contrasting black and white areas of the MRI image correspond to the disproportionate T1 and T2 proton relaxation times of various biological tissues as a consequence of differences in their compositions and proton density, resulting in distanced signal intensities. However, the limited virtue of these differences can sometimes cause low sensitivity of the technique, resulting in inadequate image contrasts for certain clinical objectives.

Table 1. Classification of magnetic NPs based on the core and coating materials and their respective applications.

| Magnetic Core | Reported Coating Materials | Application | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal | |||

| Fe | polymers | MRI, drug delivery | [45][46][47] |

| iron oxide | MRI, hyperthermia | [48] | |

| Au | drug delivery, photothermal therapy | [49] | |

| Co | organic acids | drug delivery, hyperthermia | [50] |

| polymers | MRI | [51] | |

| Au | MRI, gene transport, hyperthermia | [52][53][54][55] | |

| FeCo | graphite | MRI, optical imaging | [56][57] |

| CoFe2O4 | hyperthermia | [58] | |

| Au | MRI, medical labelling | [59] | |

| FePt | Au | MRI, photothermal therapy | [60][61] |

| organic acids/thiols | biosensors, MRI, CT | [62][63][64][65][66] | |

| SiW11O39 | hyperthermia | [67] | |

| polymer + SiO2 | drug delivery | [68] | |

| FeNi | polymers | hyperthermia | [69] |

| FeNiCo | propylene glycol | hyperthermia | [70] |

| Oxide | |||

| Fe3O4 | SiO2, TiO2 | MRI, photokilling agents | [71][72][73] |

| dextran, DMSA | MRI | [74] | |

| Au, Ag | MRI, immunosensor, photothermal therapy | [75][76][77][78] | |

| Fe2O3 | SiO2 | MRI, biolabelling | [79][80] |

| polymers | MRI, biolabelling, drug delivery, optical imaging | [81][82] | |

| MnFe2O4 | polymers and organic acids | MRI | [83][84] |

| CoFe2O4 | polymers and organic acids | MRI, drug delivery, hyperthermia | [84][85][86] |

| Au + PNA oligomers | biosensors, genomics | [87] | |

| NiFe2O4 | polymers and organic acids | drug delivery, hyperthermia | [84][88][89][90] |

| polysaccharides | MRI | [91] | |

| MnO | Au | MRI | [92] |

| polymers and organic acids | MRI | [81] | |

| SiO2 | biolabelling | [93] |

Because the relaxation process involves an interaction between the protons and their immediate molecular environment, it is possible to administer MRI contrast agents that alter the magnetic characteristics within specific tissues or anatomical regions and improve the image contrast [94][95][96]. Those contrast agents are individual molecules or particles with unpaired electrons (paramagnetic metal–ligand complexes or magnetic particles) that produce inhomogeneities in the magnetic field causing a rapid dephasing of nearby protons and change in their relaxation rate. Contrast agents can be divided into those that shorten the longitudinal recovery time, resulting in a brighter image, i.e., positive or T1 agents, and those that shorten the transversal decay time, i.e., negative or T2 agents. The principle of MRI and the use of contrast agents is shown in Figure 1. Contrast agents are used in 40–50% of all MRI examinations.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the principle behind the MRI contrast agents.

The first paramagnetic complex approved in 1987 for use in cancer patients to detect brain tumours was gadolinium(III) diethylenetetraamine pentaacetic acid (GdDTPA) [97]. With rising concerns over the safety of Gd complexes, which have been found to remain in the body after multiple MRI scans, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a series of restrictions on their use as contrast agents in 2009 [98][99]. This stimulated intense interest in creating responsive superparamagnetic T2 agents that show higher biocompatibility and safety. Currently, the majority of T2 contrast agents are iron oxide based superparamagnetic NPs (SPIONs) coated with dextran, silicates, or other polymers with variable T2 relaxivities [100][101][102]. Recent studies investigating the transformation of SPIONs into T1 contrast agents have generated some promising results, but effective contrast enhancement is still lacking, due to the unknown relaxation mechanisms, and nanoparticulate T1 contrast agents have yet to be approved for clinical use [103][104][105][106]. This flexibility makes iron oxide NPs attractive for detecting specific biological tissues, but their relatively large sizes still impede cell penetration and delivery, while lower values of their magnetic moments require increased clinical uptake to compensate for the poor contrast obtained when compared to gadolinium-based agents. Low efficacy has led to a discontinuation of a number of prominent iron oxide contrast agents in recent years [107][108][109], and currently, only ultrasmall particles (USPIONs) remain in clinical use. Superparamagnetic iron–platinum mNPs have been reported to have significantly better T2 relaxivities than SPIONs and USPIONs [110], while iron mNPs offer an order of magnitude greater susceptibility at room temperature [111][112]. As a result, these are currently agents of significant interest and the topic of much investigation, together with cobalt mNPs, whose very high saturation magnetisation (1422 emu/cm3 for cobalt compared to 395 emu/cm3 for iron oxide at room temperature) offers a larger effect on proton relaxation, promising improved MRI contrast whilst allowing smaller particle cores to be used without compromising sensitivity [51][55].

1.1.2. Magnetic Hyperthermia

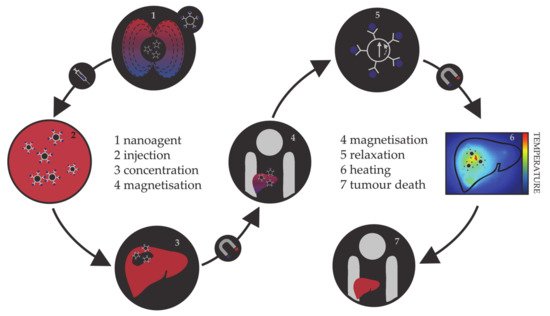

Hyperthermia, in terms of medical treatments, is defined as a moderate increase in temperature (to 40–45 °C) sufficient to cause death of tumorous cells whose vulnerability towards heat originates from the poor blood flow and insufficient oxygenation in the affected region [113][114][115]. Initially, hyperthermia treatments used water baths; later, conventional therapies proceeded to noncontact external devices for transfer of thermal energy either by irradiation or by electromagnetic waves (microwave, radiofrequency, ultrasound, or laser sources). However, the realisation of the full clinical potential of hyperthermia treatments was limited due to the inability of heat sources to target tumorous cells efficiently and locally. As the effectiveness reduces steeply with the distance from the source, targeted regions were not receiving enough thermal energy, while maximal temperature gradient was obtained on the body’s surface. However, the biggest shortcoming was the dissipation of energy that was causing serious damage in the healthy tissue situated near the main path of the radiation beam. Altogether, conventional hyperthermia showed no discrimination between targeted tissue and surrounding environment. The growing usage of magnetic nanosystems initiated an efficient solution, where the problem of an external source could now be circumvented by the intravenous administration of magnetic NPs, followed by the use of an alternating magnetic field that results in the localised transformation of electromagnetic energy into heat by means of NP relaxation mechanisms. This targeted approach allows local heating of tumorous cells with minimal impact on the surrounding tissues. The principle of magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the principle of magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia for liver cancer.

The magnetic hyperthermia nanoagents implemented thus far are mostly magnetite and maghemite NPs [116][117][118][119][120]. However, despite the promising results of preclinical trials, there are many ongoing challenges in making magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia a universal cancer treatment, including the establishment of optimal limits on the strength and frequency of the applied magnetic field, their correlation with the duration of the treatment, and determination of sufficient NP concentrations [121][122][123][124][125]. As the magnetic gradient decreases with the distance from the source of the applied magnetic field, restrictions on the human-safe magnetic field strengths impose challenges in obtaining the necessary gradients to control the residence time of NPs in the desired area. Additionally, estimates of the magnetic field strengths and gradients based on the hydrodynamic conditions of vascular vessels have shown that the highest effectiveness of magnetic targeting is in the regions of slower blood flow, which are usually near the surface [126][127][128]. Research on the internal magnets implanted in the vicinity of the targeted tissue using minimally invasive surgery is ongoing, and several studies have succeeded in simulating the interaction between an implant and a magnetic agent [129][130][131][132]. In terms of the amount of NPs that can be incorporated in a single living cell, the admissible intake is of the order of a few picograms [133][134][135]. This limit makes it essential that the nanoparticular agents have high magnetic moments, because a relatively small number of particles (between 103 and 104) has to be capable of increasing the intracellular temperature by several degrees, where mNPs have an important advantage over the relatively weak magnetic moments of iron oxides. There are several excellent reviews in the literature on the principles and requirements of magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia [136][137][138][139][140].

Nanoparticle hyperthermia can also be combined with other therapies to form multimodality treatments and provide a superior therapy outcome [141]. One possibility is to merge it with chemotherapy, where heat can enhance the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs or assist the drug uptake by increasing the local blood supply and tissue oxygenation [142][143][144]. Besides the synergy with chemotherapy, the combination of unique magnetic and optical properties in a single NP system leads to multimodal photothermal and thermal photodynamic treatments [145][146][147][148][149]. In nano-photodynamic therapy, mNPs act as photosensitiser carriers that under the irradiation with visible (VIS) and/or near-infrared (NIR) light generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) able to cause tumour degradation. Multiple studies on glioblastoma have shown that the combination of nanoparticulate hyperthermia and photodynamic treatments is quite effective to treat this type of cancer [150]. In nano-photothermal therapy, a nanosized photothermal agent is stimulated by both specific band light and vibrational energy/heat release to selectively target abnormal tissues. A number of magnetic nanomaterials with appropriate optical characteristics have been developed by bringing together a magnetic core and, for example, gold coatings, carbon nanotubes, or graphene, all of which show strong optical absorbance in the NIR optical transparency window of biological tissues. The major advantage of the combined electron–phonon and magnetic relaxations is the significant reduction in the laser power density required for efficient therapies [151][152]. Recently, a pilot study on the initial evaluation of nano-photothermal agents based on gold nanoshells in the treatment of prostate cancer confirmed the clinical safety of this combined therapy [153].

1.1.3. Targeted Drug Delivery

One of the most rapidly developing areas of modern pharmacology is targeted drug delivery, with the aim to reduce the drug intake per dose and prevent exposure of healthy tissue to chemically active analytes. In 1906, Paul Ehrlich introduced the term magic bullet, describing the drug capable of locating the causative agent of the disease and providing the adequate treatment without further distribution to unaffected areas [154]. Several decades later, the first drug delivery systems were developed, containing active medical substances attached to the surface of a carrier or encapsulated within the carrier which possesses specific cell affinity contained within molecular vectors and would disintegrate and release the capsulated drug upon contact with diseased cells [155][156][157]. Organic nanosystems (liposomes, micelles, polymer NPs) [158][159][160] together with carbon nanotubes and fullerene NPs [161][162][163] are the most often employed drug carriers, while different hormones, enzymes, peptides, antibodies, and viruses often serve as molecular vectors [164][165][166][167]. Thus far, the available carriers and capsules for targeted drug delivery have each shown several disadvantages, from limited chemical and mechanical stability of organic NPs, over the questionable toxicity of carbon-based systems, to the general susceptibility to microbiological attack, lack of control over the carrier movement and the rate of drug release, and, finally, high cost [168][169][170][171]. Hence, the search for an optimal carrier has shifted direction towards utilising the magnetically induced movement of magnetic nanosystems. Their main advantages are simple visualisation (based on the principles of MRI), easy guidance and retention in the desired area by externally applied magnetic field, and controllable drug detachment triggered by heat released in the variable magnetic field (based on the principles of magnetic hyperthermia). In addition, it is possible to engineer magnetic NPs to either avoid or interact with the immune system in specific ways [172][173].

In common with the previous two applications, most attention has been devoted to iron oxide NPs [174][175][176]. However, limitations of magnetic drug delivery have promoted the search for materials of higher magnetic moments [177] due to the decrease in the magnetic gradients connected to the distance from the source as well as to the fluid hydrodynamics correlating with the depth of the affected tissue—i.e., the same drawbacks as in hyperthermia treatments. So far, a combination of relatively strong magnetic fields with SPION drug carriers has been shown to reach an effective depth of 10–15 cm in the body [178]. Other restrictions relate to the acceptable size of the NPs; first, they have to be below the critical size for optimal magnetic properties, which is a prerequisite to avoid magnetic memory and agglomeration once the magnetic field is removed, and second, they have to be small enough such that after the attachment of drug molecules on their surface they can still effectively pass through narrow barriers [179][180]. The small size implies a reduced magnetic response and hence requires materials of high magnetisation, such as mNPs, rather than metal oxides. Recently, 5–25 nm diameter cobalt–gold mNPs with a core–shell structure and tailorable morphology were synthesised for the purpose of obtaining high-magnetisation drug carriers [181]. The major advantage of the implementation of cobalt within the mNP core is that it has a magnetic moment nearly twice that of iron oxides.

2. Features of mNPs

2.1. Electronic and Magnetic Properties of mNPs

The proper functionality of mNPs for specific applications depends on their magnetic properties, as well as their biophysical behaviour under physiological conditions. While the latter is most efficiently captured by in vivo experiments, insight into the dependence of magnetic properties of nanometre-scale particles on their size, composition, and morphology can be reliably obtained by computer modelling techniques.

Magnetic properties of mNPs can be classified as intrinsic or extrinsic. The former are more important since they are derived from the interactions on an atomic length scale and highly depend on chemical composition and grain size, shape, and crystal microstructure. Additionally, they are much more affected by surface effects and therefore give rise to specific manifestations, such as superparamagnetism, that can only be found at the nanoscale level. These properties include magnetic saturation, anisotropy, and the Curie temperature.

Intrinsically, classification of mNPs based on the ordering of their magnetic moments corresponds to the classes of bulk metallic materials, and hence there are paramagnetic and ferromagnetic mNPs. Those that are paramagnetic exhibit no collective magnetic interactions and they are not magnetically ordered; however, in the presence of a magnetic field, there is a partial alignment of the atomic magnetic moments in the direction of the field, resulting in a net positive magnetisation. mNPs belonging to the ferromagnetic class exhibit long-range magnetic order below a certain critical temperature, resulting in large net magnetisation even in the absence of the magnetic field. If the diameter of the mNP is larger than the critical value, DC, coupling interactions cause mutual spin alignment of adjacent atoms over large volume regions called magnetic domains. Domains are separated by domain walls, in which the direction of magnetisation of dipoles rotates smoothly from the direction in one domain towards the direction in the next. Once the diameter falls under the critical value (typically between 3 and 50 nm), mNPs can no longer accommodate a wall and each of them becomes a single domain. Additionally, since each domain is also a separate particle, there can be no interactions or ordering of domains within a sample, and particles do not retain any net magnetisation once the external field has been removed. This phenomenon is known as superparamagnetism. Superparamagnetic mNPs are, as the name suggests, much alike paramagnetic mNPs apart from the fact that this property arises from ferromagnetism. Their normal ferromagnetic movements combined with very short relaxation times enable the spins to randomly flip direction under the influence of temperature or to rapidly follow directional changes in the applied field. The temperature above which the thermal energy will be sufficient to suppress ferromagnetic behaviour is called the blocking temperature, TB. Below TB, the magnetisation is relatively stable and shows ferromagnetic behaviour, while for T > TB, the spins are as free as in a paramagnetic system and particles behave superparamagnetically. Blocking temperatures for most mNPs are below 100 K [182][183][184][185], and their behaviour is therefore paramagnetic, as for most temperatures they are only magnetised in the presence of the external field, but their magnetisation values are in the range of ferromagnetic substances. Moreover, the strength of the external field needed to reach the saturation point of superparamagnetic mNPs is comparable to that of ferromagnetic mNPs.

The highest magnetisation that mNPs can obtain when exposed to a sufficiently large magnetic field is called the saturation magnetisation, MS. It is the maximum value of the material’s permeability curve, where permeability, μ, is the measure of magnetisation that a material obtains in response to an applied magnetic field (total magnetisation of material per volume). It is often correlated with the ratio of magnetisation to the intensity of an applied magnetic field H, which is known as the magnetic susceptibility, χ, and describes whether a material is attracted into or repelled out of a magnetic field. The magnitude of saturation is a function of temperature; once it is reached, no further increase in magnetisation can occur even by increasing the strength of the applied field. The unique temperature limit at which ferromagnetic mNPs can maintain permanent magnetisation is the Curie temperature, TC. Notably, when the mNP size is reduced from multidomain to a single domain, the magnitude of MS decreases due to the increment in the spin disorder effect at the surface; thus, the MS value is also directly proportional to the size of mNPs.

In almost all cases, magnetic materials contain some type of anisotropy that affects their magnetic behaviour. The most common types of anisotropy are (a) magneto-crystalline anisotropy (MCA), (b) surface anisotropy, (c) shape anisotropy, (d) exchange anisotropy, and (e) induced anisotropy (by stress, for example), where MCA and shape anisotropy are the most important in mNPs. Magneto-crystalline anisotropy is the tendency of the magnetisation to align along a specific spatial direction rather than randomly fluctuate over time. It arises from spin–orbit interactions and energetically favours alignment of the magnetic moments along the so-called easy axis. Factors affecting the MCA are the type of material, temperature, and impurities, whereas it does not depend on the shape and size of the mNP. Morphology effects are included in the shape anisotropy. Stress anisotropy implies that magnetisation might change with stress, for example when the surfaces are modified through ligand adsorption, which means that the surface structure can significantly influence the total anisotropy. Hence, due to the large ratio of surface to bulk atoms, the surface anisotropy of mNPs could be very significant, and the coating of mNPs can therefore have a strong influence on their magnetic anisotropies. Different types of anisotropy are often expressed simply as magnetic anisotropy energy (MAE), which determines the stability of the magnetisation by describing the dependence of the internal energy on the direction of spontaneous magnetisation. It has a strong effect on the values of extrinsic properties.

Extrinsic properties of mNPs are not as essential as the intrinsic. They are derived from long-range interactions and include magnetic coercivity and remnant magnetisation (remanence), which are dependent on microstructural factors, such as the orientation of intermetallic phases.

Magnetic coercivity, HC, can be described as a resistance of a magnetic material to changes in magnetisation, and it is equivalent to the magnitude of the external magnetic field needed to demagnetise material that has previously been magnetised to its saturation point. Ferromagnetic mNPs that have reached saturation cannot return to zero magnetisation in the same direction once the applied field has been removed, and the magnetic field is therefore applied in the opposite direction. This process leads to the creation of a loop known as hysteresis. Hysteresis loops indicate the correlation between the magnetic field and the induced flux density (B/H curves). Superparamagnetic mNPs each have only one domain, and no hysteresis loop is obtained when the applied field is reversed. Remnant magnetisation, Mr, is magnetisation left after the magnetic field has been removed. Once the saturation has occurred and a magnetic field is no longer applied, ferromagnetic mNPs will produce an auxiliary magnetic field and resist sudden change to remain magnetised. In contrast, superparamagnetic mNPs will behave as paramagnets with instant need for demagnetisation and negligible Mr. This property allows for ferromagnetic mNPs to gain magnetic memory.

2.2. Biomedically Desired Properties of mNPs

Specifics of the application of interest govern the desired properties of materials used, as was described briefly for the diagnostics and therapy methods in the previous section. In biomedicine, the safety of the treatment towards a patient is the highest priority, and hence superparamagnetic mNPs are preferred because they are magnetised only under the influence of an external magnetic field and quickly demagnetise otherwise, which makes them safer for the human body. This implies that no coercive forces or remanence exist, preventing magnetic interactions between particles and their aggregation, which could lead to adverse problems derived from the formation of clots in the blood circulation system. Saturation magnetisation is also a substantial factor for two reasons: (1) mNPs with high MS show a more prominent response to the external magnetic field; (2) high MS makes the movements of mNPs more controllable and guarantees efficient response to the magnetic field, implying reduced time of residence and lower required dosages of mNPs. MS is dependent on the mNP magnetic moment, size, and distribution, and it is thus important to take them into consideration. An increase in size yields higher MS, but above the critical diameter, mNPs become ferromagnetic and show undesired behaviour due to the formation of agglomerates and magnetic memory. Moreover, very small diameter sizes are highly desirable to reach regions of limited access; in order to cross the blood–brain barrier, for example, a magnetic core size of d ≈ 12 nm or less is required. Thus, a suitable balance should be found between the size distribution and magnetic properties. Since mNP-based therapies work by directing the mNPs to a target site using an external magnetic field, magnetic anisotropy is also a very important factor.

Alongside these general requirements that are applicable to all biomedical applications, to enhance the performance of mNPs within MRI diagnostics and hyperthermia therapy it is essential to gain insight into the inherent mechanisms behind their magnetic processes and assess the properties of mNPs and external magnetic field parameters for optimal treatment results.

References

- Tabor, C.; Narayanan, R.; El-Sayed, M.A. Catalysis with transition metal nanoparticles in colloidal solution: Heterogeneous or homogeneous? Model Syst. Catal. Single Cryst. Support. Enzym. Mimics 2010, 395–414.

- Garcia, M.A. Surface plasmons in metallic nanoparticles: Fundamentals and applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2012, 45, 389501.

- An, K.; Somorjai, G.A. Size and Shape Control of Metal Nanoparticles for Reaction Selectivity in Catalysis. ChemCatChem 2012, 4, 1512–1524.

- Zhang, L.; Anderson, R.M.; Crooks, R.M.; Henkelman, G. Correlating structure and function of metal nanoparticles for catalysis. Surf. Sci. 2015, 640, 65–72.

- Ko, S.H.; Park, I.; Pan, H.; Grigoropoulos, C.P.; Pisano, A.P.; Luscombe, C.K.; Fréchet, J.M.J. Direct nanoimprinting of metal nanoparticles for nanoscale electronics fabrication. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 1869–1877.

- Son, Y.; Yeo, J.; Moon, H.; Lim, T.W.; Hong, S.; Nam, K.H.; Yoo, S.; Grigoropoulos, C.P.; Yang, D.Y.; Ko, S.H. Nanoscale electronics: Digital fabrication by direct femtosecond laser processing of metal nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 3176–3181.

- Liu, S.; Yuen, M.C.; White, E.L.; Boley, J.W.; Deng, B.; Cheng, G.J.; Kramer-Bottiglio, R. Laser Sintering of Liquid Metal Nanoparticles for Scalable Manufacturing of Soft and Flexible Electronics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 28232–28241.

- Sosa, I.O.; Noguez, C.; Barrera, R.G. Optical properties of metal nanoparticles with arbitrary shapes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 6269–6275.

- Murphy, C.J.; Sau, T.K.; Gole, A.M.; Orendorff, C.J.; Gao, J.; Gou, L.; Hunyadi, S.E.; Li, T. Anisotropic metal nanoparticles: Synthesis, assembly, and optical applications. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 13857–13870.

- Zijlstra, P.; Orrit, M. Single metal nanoparticles: Optical detection, spectroscopy and applications. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2011, 74, 106401.

- Kelly, K.L.; Coronado, E.; Zhao, L.L.; Schatz, G.C. The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 668–677.

- Wan, D.; Chen, H.L.; Tseng, S.C.; Wang, L.A.; Chen, Y.P. One-shot deep-UV pulsed-laser-induced photomodification of hollow metal nanoparticles for high-density data storage on flexible substrates. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 165–173.

- Sun, X.; Huang, Y.; Nikles, D.E. FePt and CoPt magnetic nanoparticles film for future high density data storage media. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2004, 1, 328–346.

- Kang, M.; Baeg, K.J.; Khim, D.; Noh, Y.Y.; Kim, D.Y. Printed, flexible, organic nano-floating-gate memory: Effects of metal nanoparticles and blocking dielectrics on memory characteristics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 3503–3512.

- Liao, H.; Nehl, C.L.; Hafner, J.H. Biomedical applications of plasmon resonant metal nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2006, 1, 201–208.

- Zeisberger, M.; Dutz, S.; Müller, R.; Hergt, R.; Matoussevitch, N.; Bönnemann, H. Metallic cobalt nanoparticles for heating applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 311, 224–227.

- Cherukuri, P.; Glazer, E.S.; Curley, S.A. Targeted hyperthermia using metal nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 339–345.

- Sharma, H.; Mishra, P.K.; Talegaonkar, S.; Vaidya, B. Metal nanoparticles: A theranostic nanotool against cancer. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 1143–1151.

- Rai, M.; Ingle, A.P.; Birla, S.; Yadav, A.; Santos, C.A. Dos Strategic role of selected noble metal nanoparticles in medicine. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 696–719.

- Xia, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Lim, B.; Skrabalak, S.E. Shape-controlled synthesis of metal nanocrystals: Simple chemistry meets complex physics? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 60–103.

- Vajda, S.; Pellin, M.J.; Greeley, J.P.; Marshall, C.L.; Curtiss, L.A.; Ballentine, G.A.; Elam, J.W.; Catillon-Mucherie, S.; Redfern, P.C.; Mehmood, F.; et al. Subnanometre platinum clusters as highly active and selective catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 213–216.

- Grassian, V.H. When size really matters: Size-dependent properties and surface chemistry of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles in gas and liquid phase environments. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 18303–18313.

- Carlson, C.; Hussein, S.M.; Schrand, A.M.; Braydich-Stolle, L.K.; Hess, K.L.; Jones, R.L.; Schlager, J.J. Unique cellular interaction of silver nanoparticles: Size-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 13608–13619.

- Balamurugan, B.; Maruyama, T. Evidence of an enhanced interband absorption in Au nanoparticles: Size-dependent electronic structure and optical properties. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 143105.

- Xiong, S.; Qi, W.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, M.; Li, Y. Universal relation for size dependent thermodynamic properties of metallic nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 10652–10660.

- Haldar, K.K.; Kundu, S.; Patra, A. Core-size-dependent catalytic properties of bimetallic Au/Ag core-shell nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 21946–21953.

- Neubauer, N.; Palomaeki, J.; Karisola, P.; Alenius, H.; Kasper, G. Size-dependent ROS production by palladium and nickel nanoparticles in cellular and acellular environments - An indication for the catalytic nature of their interactions. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 1059–1066.

- Dong, C.; Lian, C.; Hu, S.; Deng, Z.; Gong, J.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J. Size-dependent activity and selectivity of carbon dioxide photocatalytic reduction over platinum nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1252.

- Mourdikoudis, S.; Pallares, R.M.; Thanh, N.T.K. Characterization techniques for nanoparticles: Comparison and complementarity upon studying nanoparticle properties. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 12871–12934.

- Yan, Z.; Taylor, M.G.; Mascareno, A.; Mpourmpakis, G. Size-, Shape-, and Composition-Dependent Model for Metal Nanoparticle Stability Prediction. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 2696–2704.

- Taylor, M.G.; Austin, N.; Gounaris, C.E.; Mpourmpakis, G. Catalyst Design Based on Morphology- and Environment-Dependent Adsorption on Metal Nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6296–6301.

- Kozlov, S.M.; Kovács, G.; Ferrando, R.; Neyman, K.M. How to determine accurate chemical ordering in several nanometer large bimetallic crystallites from electronic structure calculations. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 3868–3880.

- Ferrando, R.; Fortunelli, A.; Rossi, G. Quantum effects on the structure of pure and binary metallic nanoclusters. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2005, 72, 085449.

- Zhu, B.; Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Gao, Y. Shape Evolution of Metal Nanoparticles in Water Vapor Environment. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 2628–2632.

- Sangaiya, P.; Jayaprakash, R. A Review on Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 3397–3413.

- Lima-Tenório, M.K.; Gómez Pineda, E.A.; Ahmad, N.M.; Fessi, H.; Elaissari, A. Magnetic nanoparticles: In vivo cancer diagnosis and therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 493, 313–327.

- Hervault, A.; Thanh, N.T.K. Magnetic nanoparticle-based therapeutic agents for thermo-chemotherapy treatment of cancer. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 11553–11573.

- Laurent, S.; Dutz, S.; Häfeli, U.O.; Mahmoudi, M. Magnetic fluid hyperthermia: Focus on superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 166, 8–23.

- Singh, A.; Sahoo, S.K. Magnetic nanoparticles: A novel platform for cancer theranostics. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 474–481.

- Périgo, E.A.; Hemery, G.; Sandre, O.; Ortega, D.; Garaio, E.; Plazaola, F.; Teran, F.J. Fundamentals and advances in magnetic hyperthermia. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2, 041302.

- Hedayatnasab, Z.; Abnisa, F.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Review on magnetic nanoparticles for magnetic nanofluid hyperthermia application. Mater. Des. 2017, 123, 174–196.

- Felder, R.C.; Parker, J.A. Principles of nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Med. Instrum. 1985, 19, 248–256.

- Geva, T. Magnetic resonance imaging: Historical perspective. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2006, 8, 573–580.

- Grover, V.P.B.; Tognarelli, J.M.; Crossey, M.M.E.; Cox, I.J.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; McPhail, M.J.W. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Principles and Techniques: Lessons for Clinicians. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2015, 5, 246–255.

- Nattama, S.; Rahimi, M.; Wadajkar, A.S.; Koppolu, B.; Hua, J.; Nwariaku, F.; Nguyen, K.T. Characterization of polymer coated magnetic nanoparticles for targeted treatment of cancer. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Dallas Engineering in Medicine and Biology Workshop, Dallas, TX, USA, 11–12 November 2007; 2007; pp. 35–38.

- Rahimi, M.; Wadajkar, A.; Subramanian, K.; Yousef, M.; Cui, W.; Hsieh, J.T.; Nguyen, K.T. In vitro evaluation of novel polymer-coated magnetic nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2010, 6, 672–680.

- Mu, Q.; Yang, L.; Davis, J.C.; Vankayala, R.; Hwang, K.C.; Zhao, J.; Yan, B. Biocompatibility of polymer grafted core/shell iron/carbon nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5083–5090.

- Zhang, G.; Liao, Y.; Baker, I. Surface engineering of core/shell iron/iron oxide nanoparticles from microemulsions for hyperthermia. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2010, 30, 92–97.

- Jafari, T.; Simchi, A.; Khakpash, N. Synthesis and cytotoxicity assessment of superparamagnetic iron-gold core-shell nanoparticles coated with polyglycerol. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 345, 64–71.

- Ansari, S.M.; Bhor, R.D.; Pai, K.R.; Sen, D.; Mazumder, S.; Ghosh, K.; Kolekar, Y.D.; Ramana, C.V. Cobalt nanoparticles for biomedical applications: Facile synthesis, physiochemical characterization, cytotoxicity behavior and biocompatibility. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 414, 171–187.

- Parkes, L.M.; Hodgson, R.; Lu, L.T.; Tung, L.D.; Robinson, I.; Fernig, D.G.; Thanh, N.T.K. Cobalt nanoparticles as a novel magnetic resonance contrast agent-relaxivities at 1.5 and 3 Tesla. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2008, 3, 150–156.

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, L.; Dong, L.; Shi, C.; Hu, M.J.; Xu, Y.J.; Wen, L.P.; Yu, S.H. Hydrophilic yolk/shell nanospheres: Synthesis, assembly, and application to gene delivery. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1407–1411.

- Hrubovčák, P.; Zeleňáková, A.; Zeleňák, V.; Kovác, J. Superparamagnetism in cobalt nanoparticles coated by protective gold layer. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2014, 126, 216–217.

- Marbella, L.E.; Andolina, C.M.; Smith, A.M.; Hartmann, M.J.; Dewar, A.C.; Johnston, K.A.; Daly, O.H.; Millstone, J.E. Gold-cobalt nanoparticle alloys exhibiting tunable compositions, near-infrared emission, and high T2relaxivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 6532–6539.

- Bouchard, L.; Anwar, M.S.; Liu, G.L.; Hann, B.; Xie, Z.H.; Gray, J.W.; Wang, X.; Pines, A.; Chen, F.F. Picomolar sensitivity MRI and photoacoustic imaging of cobalt nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 4085–4089.

- Kosuge, H.; Sherlock, S.P.; Kitagawa, T.; Terashima, M.; Barral, J.K.; Nishimura, D.G.; Dai, H.; McConnell, M.V. FeCo/graphite nanocrystals for multi-modality imaging of experimental vascular inflammation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, 14523.

- Seo, W.S.; Lee, J.H.; Sun, X.; Suzuki, Y.; Mann, D.; Liu, Z.; Terashima, M.; Yang, P.C.; McConnell, M.V.; Nishimura, D.G.; et al. FeCo/graphitic-shell nanocrystals as advanced magnetic-resonance-imaging and near-infrared agents. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 971–976.

- Habib, A.H.; Ondeck, C.L.; Chaudhary, P.; Bockstaller, M.R.; McHenry, M.E. Evaluation of iron-cobalt/ferrite core-shell nanoparticles for cancer thermotherapy. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 07A307.

- Xu, Y.H.; Bai, J.; Wang, J.P. High-magnetic-moment multifunctional nanoparticles for nanomedicine applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 311, 131–134.

- Chen, C.L.; Kuo, L.R.; Lee, S.Y.; Hwu, Y.K.; Chou, S.W.; Chen, C.C.; Chang, F.H.; Lin, K.H.; Tsai, D.H.; Chen, Y.Y. Photothermal cancer therapy via femtosecond-laser-excited FePt nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1128–1134.

- Choi, J.S.; Jun, Y.W.; Yeon, S.I.; Kim, H.C.; Shin, J.S.; Cheon, J. Biocompatible heterostructured nanoparticles for multimodal biological detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 15982–15983.

- Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H.; Fang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, S. One-pot synthesis of amphiphilic superparamagnetic FePt nanoparticles and magnetic resonance imaging in vitro. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322, 973–977.

- Liu, Y.; Wu, P.C.; Guo, S.; Chou, P.T.; Deng, C.; Chou, S.W.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, T.M. Low-toxicity FePt nanoparticles for the targeted and enhanced diagnosis of breast tumors using few centimeters deep whole-body photoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics 2020, 19, 100179.

- Liang, S.Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.H.; Wu, Q.Z.; Yang, X.L. Water-soluble l-cysteine-coated FePt nanoparticles as dual MRI/CT imaging contrast agent for glioma. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 2325–2333.

- Chou, S.W.; Shau, Y.H.; Wu, P.C.; Yang, Y.S.; Shieh, D.B.; Chen, C.C. In vitro and in vivo studies of fept nanoparticles for dual modal CT/MRI molecular imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13270–13278.

- Sun, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Dong, M.; Fu, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, X.; Wu, Q.; Qiu, T.; Wan, T.; et al. Influences of surface coatings and components of FePt nanoparticles on the suppression of glioma cell proliferation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 3295–3307.

- Seemann, K.M.; Luysberg, M.; Révay, Z.; Kudejova, P.; Sanz, B.; Cassinelli, N.; Loidl, A.; Ilicic, K.; Multhoff, G.; Schmid, T.E. Magnetic heating properties and neutron activation of tungsten-oxide coated biocompatible FePt core-shell nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 2015, 197, 131–137.

- Fuchigami, T.; Kawamura, R.; Kitamoto, Y.; Nakagawa, M.; Namiki, Y. A magnetically guided anti-cancer drug delivery system using porous FePt capsules. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 1682–1687.

- Salati, A.; Ramazani, A.; Almasi Kashi, M. Deciphering magnetic hyperthermia properties of compositionally and morphologically modulated FeNi nanoparticles using first-order reversal curve analysis. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 025707.

- Salati, A.; Ramazani, A.; Almasi Kashi, M. Tuning hyperthermia properties of FeNiCo ternary alloy nanoparticles by morphological and magnetic characteristics. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 498, 166172.

- Liu, H.M.; Wu, S.H.; Lu, C.W.; Yao, M.; Hsiao, J.K.; Hung, Y.; Lin, Y.S.; Mou, C.Y.; Yang, C.S.; Huang, D.M.; et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles improve magnetic labeling efficiency in human stem cells. Small 2008, 4, 619–626.

- Tanaka, K.; Narita, A.; Kitamura, N.; Uchiyama, W.; Morita, M.; Inubushi, T.; Chujo, Y. Preparation for highly sensitive MRI contrast agents using core/shell type nanoparticles consisting of multiple SPIO cores with thin silica coating. Langmuir 2010, 26, 11759–11762.

- Chen, W.-J.; Tsai, P.-J.; Chen, Y.-C. Functional Fe3O4/TiO2 Core/Shell Magnetic Nanoparticles as Photokilling Agents for Pathogenic Bacteria. Small 2008, 4, 485–491.

- Estelrich, J.; Sánchez-Martín, M.J.; Busquets, M.A. Nanoparticles in magnetic resonance imaging: From simple to dual contrast agents. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 1727–1741.

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, S.; Song, X.; Huang, J.; Yan, M.; Yu, J. Core-shell Fe3O4-Au magnetic nanoparticles based nonenzymatic ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescence immunosensor using quantum dots functionalized graphene sheet as labels. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 770, 132–139.

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Jiang, T.; Wang, F.; Qing, Y.; Bu, S.; Zhou, J. Dual-functional Fe3O4@SiO2@Ag triple core-shell microparticles as an effective SERS platform for adipokines detection. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 535, 24–33.

- Wang, L.; Bai, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y. Multifunctional nanoparticles displaying magnetization and near-IR absorption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2439–2442.

- Qiu, J.D.; Xiong, M.; Liang, R.P.; Peng, H.P.; Liu, F. Synthesis and characterization of ferrocene modified Fe3O4@Au magnetic nanoparticles and its application. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 2649–2653.

- Caizer, C.; Hrianca, I. The temperature dependence of saturation magnetization of γ-Fe2O3/SiO2 magnetic nanocomposite. Ann. Phys. 2003, 12, 115–122.

- Pinho, S.L.C.; Pereira, G.A.; Voisin, P.; Kassem, J.; Bouchaud, V.; Etienne, L.; Peters, J.A.; Carlos, L.; Mornet, S.; Geraldes, C.F.G.C.; et al. Fine tuning of the relaxometry of γ-Fe2O3@SiO2 nanoparticles by tweaking the silica coating thickness. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 5339–5349.

- Park, J.Y.; Choi, E.S.; Baek, M.J.; Lee, G.H.; Woo, S.; Chang, Y. Water-soluble Ultra Small paramagnetic or superparamagnetic metal oxide nanoparticles for molecular MR imaging. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 2477–2481.

- Schweiger, C.; Pietzonka, C.; Heverhagen, J.; Kissel, T. Novel magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles coated with poly(ethylene imine)-g-poly(ethylene glycol) for potential biomedical application: Synthesis, stability, cytotoxicity and MR imaging. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 408, 130–137.

- Zhao, Z.; Sun, C.; Bao, J.; Yang, L.; Wei, R.; Cheng, J.; Lin, H.; Gao, J. Surface manganese substitution in magnetite nanocrystals enhances: T1 contrast ability by increasing electron spin relaxation. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 401–413.

- Demirci Dönmez, C.E.; Manna, P.K.; Nickel, R.; Aktürk, S.; Van Lierop, J. Comparative Heating Efficiency of Cobalt-, Manganese-, and Nickel-Ferrite Nanoparticles for a Hyperthermia Agent in Biomedicines. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 6858–6866.

- Amiri, S.; Shokrollahi, H. The role of cobalt ferrite magnetic nanoparticles in medical science. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 1–8.

- Dey, C.; Baishya, K.; Ghosh, A.; Goswami, M.M.; Ghosh, A.; Mandal, K. Improvement of drug delivery by hyperthermia treatment using magnetic cubic cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 427, 168–174.

- Pita, M.; Abad, J.M.; Vaz-Dominguez, C.; Briones, C.; Mateo-Martí, E.; Martín-Gago, J.A.; del Puerto Morales, M.; Fernández, V.M. Synthesis of cobalt ferrite core/metallic shell nanoparticles for the development of a specific PNA/DNA biosensor. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 321, 484–492.

- Dumitrescu, A.M.; Slatineanu, T.; Poiata, A.; Iordan, A.R.; Mihailescu, C.; Palamaru, M.N. Advanced composite materials based on hydrogels and ferrites for potential biomedical applications. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 455, 185–194.

- Lasheras, X.; Insausti, M.; Gil De Muro, I.; Garaio, E.; Plazaola, F.; Moros, M.; De Matteis, L.; De La Fuente, J.; Lezama, L.M. Chemical Synthesis and Magnetic Properties of Monodisperse Nickel Ferrite Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 3492–3500.

- Menelaou, M.; Georgoula, K.; Simeonidis, K.; Dendrinou-Samara, C. Evaluation of nickel ferrite nanoparticles coated with oleylamine by NMR relaxation measurements and magnetic hyperthermia. Dalt. Trans. 2014, 43, 3626–3636.

- Ahmad, T.; Bae, H.; Iqbal, Y.; Rhee, I.; Hong, S.; Chang, Y.; Lee, J.; Sohn, D. Chitosan-coated nickel-ferrite nanoparticles as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 381, 151–157.

- Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, J.; Lei, S.; Cai, S.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Z.; et al. Porous gold nanocluster-decorated manganese monoxide nanocomposites for microenvironment-activatable MR/photoacoustic/CT tumor imaging. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 3631–3638.

- Kim, T.; Momin, E.; Choi, J.; Yuan, K.; Zaidi, H.; Kim, J.; Park, M.; Lee, N.; McMahon, M.T.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; et al. Mesoporous silica-coated hollow manganese oxide nanoparticles as positive T1 contrast agents for labeling and MRI tracking of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 2955–2961.

- Caravan, P.; Ellison, J.J.; McMurry, T.J.; Lauffer, R.B. Gadolinium(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: Structure, dynamics, and applications. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 2293–2352.

- Na, H.B.; Song, I.C.; Hyeon, T. Inorganic nanoparticles for MRI contrast agents. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2133–2148.

- Wahsner, J.; Gale, E.M.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Caravan, P. Chemistry of MRI contrast agents: Current challenges and new frontiers. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 957–1057.

- De Leõn-Rodríguez, L.M.; Martins, A.F.; Pinho, M.C.; Rofsky, N.M.; Sherry, A.D. Basic MR relaxation mechanisms and contrast agent design. J. Magnet. Reson. Imaging 2015, 42, 545–565.

- Moreno-Romero, J.A.; Segura, S.; Mascaró, J.M.; Cowper, S.E.; Julià, M.; Poch, E.; Botey, A.; Herrero, C. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: A case series suggesting gadolinium as a possible aetiological factor. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 157, 783–787.

- Hasebroock, K.M.; Serkova, N.J. Toxicity of MRI and CT contrast agents. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2009, 5, 403–416.

- Khalkhali, M.; Rostamizadeh, K.; Sadighian, S.; Khoeini, F.; Naghibi, M.; Hamidi, M. The impact of polymer coatings on magnetite nanoparticles performance as MRI contrast agents: A comparative study. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 23, 45.

- Fernández-Barahona, I.; Muñoz-Hernando, M.; Ruiz-Cabello, J.; Herranz, F.; Pellico, J. Iron oxide nanoparticles: An alternative for positive contrast in magnetic resonance imaging. Inorganics 2020, 8, 28.

- Tromsdorf, U.I.; Bruns, O.T.; Salmen, S.C.; Beisiegel, U.; Weller, H. A highly effective, nontoxic T1 MR contrast agent based on ultrasmall PEGylated iron oxide nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 4434–4440.

- Iqbal, M.Z.; Ma, X.; Chen, T.; Zhang, L.; Ren, W.; Xiang, L.; Wu, A. Silica-coated super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONPs): A new type contrast agent of T1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 5172–5181.

- Alipour, A.; Soran-Erdem, Z.; Utkur, M.; Sharma, V.K.; Algin, O.; Saritas, E.U.; Demir, H.V. A new class of cubic SPIONs as a dual-mode T1 and T2 contrast agent for MRI. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2018, 49, 16–24.

- Jeon, M.; Halbert, M.V.; Stephen, Z.R.; Zhang, M. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as T1 Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Fundamentals, Challenges, Applications, and Prospectives. Adv. Mater. 2020, 33, 1906539.

- Cao, Y.; Mao, Z.; He, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, R. Extremely Small Iron Oxide Nanoparticle-Encapsulated Nanogels as a Glutathione-Responsive T1Contrast Agent for Tumor-Targeted Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 26973–26981.

- Kiessling, F.; Mertens, M.E.; Grimm, J.; Lammers, T. Nanoparticles for imaging: Top or flop? Radiology 2014, 273, 10–28.

- Wang, Y.-X.J. Superparamagnetic iron oxide based MRI contrast agents: Current status of clinical application. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2011, 1, 35–40.

- Wang, Y.-X.J. Current status of superparamagnetic iron oxide contrast agents for liver magnetic resonance imaging. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 13400.

- Taylor, R.M.; Huber, D.L.; Monson, T.C.; Esch, V.; Sillerud, L.O. Structural and magnetic characterization of superparamagnetic iron platinum nanoparticle contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Nanotechnol. Microelectron. Mater. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2012, 30, 02C101.

- Carpenter, E.E. Iron nanoparticles as potential magnetic carriers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2001, 225, 17–20.

- Hadjipanayis, C.G.; Bonder, M.J.; Balakrishnan, S.; Wang, X.; Mao, H.; Hadjipanayis, G.C. Metallic iron nanoparticles for MRI contrast enhancement and local hyperthermia. Small 2008, 4, 1925–1929.

- Bergs, J.W.J.; Franken, N.A.P.; Haveman, J.; Geijsen, E.D.; Crezee, J.; van Bree, C. Hyperthermia, cisplatin and radiation trimodality treatment: A promising cancer treatment? A review from preclinical studies to clinical application. Int. J. Hyperth. 2007, 23, 329–341.

- Chicheł, A.; Skowronek, J.; Kubaszewska, M.; Kanikowski, M. Hyperthermia - Description of a method and a review of clinical applications. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2007, 12, 267–275.

- Saniei, N. Hyperthermia and cancer treatment. Heat Transf. Eng. 2009, 30, 915–917.

- Thomas, L.A.; Dekker, L.; Kallumadil, M.; Southern, P.; Wilson, M.; Nair, S.P.; Pankhurst, Q.A.; Parkin, I.P. Carboxylic acid-stabilised iron oxide nanoparticles for use in magnetic hyperthermia. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 6529–6535.

- Shah, R.R.; Davis, T.P.; Glover, A.L.; Nikles, D.E.; Brazel, C.S. Impact of magnetic field parameters and iron oxide nanoparticle properties on heat generation for use in magnetic hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 387, 96–106.

- Bauer, L.M.; Situ, S.F.; Griswold, M.A.; Samia, A.C.S. High-performance iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic particle imaging-guided hyperthermia (hMPI). Nanoscale 2016, 8, 12162–12169.

- Abenojar, E.C.; Wickramasinghe, S.; Bas-Concepcion, J.; Samia, A.C.S. Structural effects on the magnetic hyperthermia properties of iron oxide nanoparticles. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2016, 26, 440–448.

- Jeyadevan, B. Present status and prospects of magnetite nanoparticles-based hyperthermia. J. Ceram. Soc. Japan 2010, 118, 391–401.

- Maier-Hauff, K.; Rothe, R.; Scholz, R.; Gneveckow, U.; Wust, P.; Thiesen, B.; Feussner, A.; Deimling, A.; Waldoefner, N.; Felix, R.; et al. Intracranial thermotherapy using magnetic nanoparticles combined with external beam radiotherapy: Results of a feasibility study on patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neurooncol. 2007, 81, 53–60.

- Johannsen, M.; Gneveckow, U.; Taymoorian, K.; Thiesen, B.; Waldöfner, N.; Scholz, R.; Jung, K.; Jordan, A.; Wust, P.; Loening, S.A. Morbidity and quality of life during thermotherapy using magnetic nanoparticles in locally recurrent prostate cancer: Results of a prospective phase I trial. Int. J. Hyperth. 2007, 23, 315–323.

- Johannsen, M.; Gneveckow, U.; Thiesen, B.; Taymoorian, K.; Cho, C.H.; Waldöfner, N.; Scholz, R.; Jordan, A.; Loening, S.A.; Wust, P. Thermotherapy of Prostate Cancer Using Magnetic Nanoparticles: Feasibility, Imaging, and Three-Dimensional Temperature Distribution. Eur. Urol. 2007, 52, 1653–1662.

- Dutz, S.; Hergt, R. Magnetic nanoparticle heating and heat transfer on a microscale: Basic principles, realities and physical limitations of hyperthermia for tumour therapy. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 790–800.

- Nieskoski, M.D.; Trembly, B.S. Comparison of a single optimized coil and a Helmholtz pair for magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 61, 1642–1650.

- Ruuge, E.K.; Rusetski, A.N. Magnetic fluids as drug carriers: Targeted transport of drugs by a magnetic field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1993, 122, 335–339.

- Voltairas, P.A.; Fotiadis, D.I.; Michalis, L.K. Hydrodynamics of magnetic drug targeting. J. Biomech. 2002, 35, 813–821.

- Grief, A.D.; Richardson, G. Mathematical modelling of magnetically targeted drug delivery. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 293, 455–463.

- Iacob, G.; Rotariu, O.; Strachan, N.J.C.; Häfeli, U.O. Magnetizable needles and wires - Modeling an efficient way to target magnetic microspheres in vivo. Biorheology 2004, 41, 599–612.

- Rosengart, A.J.; Kaminski, M.D.; Chen, H.; Caviness, P.L.; Ebner, A.D.; Ritter, J.A. Magnetizable implants and functionalized magnetic carriers: A novel approach for noninvasive yet targeted drug delivery. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 293, 633–638.

- Rotariu, O.; Strachan, N.J.C. Modelling magnetic carrier particle targeting in the tumor microvasculature for cancer treatment. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 293, 639–646.

- Yellen, B.B.; Forbes, Z.G.; Halverson, D.S.; Fridman, G.; Barbee, K.A.; Chorny, M.; Levy, R.; Friedman, G. Targeted drug delivery to magnetic implants for therapeutic applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 293, 647–654.

- Maier-Hauff, K.; Ulrich, F.; Nestler, D.; Niehoff, H.; Wust, P.; Thiesen, B.; Orawa, H.; Budach, V.; Jordan, A. Efficacy and safety of intratumoral thermotherapy using magnetic iron-oxide nanoparticles combined with external beam radiotherapy on patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neurooncol. 2011, 103, 317–324.

- Asín, L.; Ibarra, M.R.; Tres, A.; Goya, G.F. Controlled cell death by magnetic hyperthermia: Effects of exposure time, field amplitude, and nanoparticle concentration. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 1319–1327.

- Skumiel, A.; Kaczmarek, K.; Flak, D.; Rajnak, M.; Antal, I.; Brząkała, H. The influence of magnetic nanoparticle concentration with dextran polymers in agar gel on heating efficiency in magnetic hyperthermia. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 304, 112734.

- Kumar, B.; Jalodia, K.; Kumar, P.; Gautam, H.K. Recent advances in nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2017, 41, 260–268.

- Hergt, R.; Dutz, S.; Müller, R.; Zeisberger, M. Magnetic particle hyperthermia: Nanoparticle magnetism and materials development for cancer therapy. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, S2919.

- Vallejo-Fernandez, G.; Whear, O.; Roca, A.G.; Hussain, S.; Timmis, J.; Patel, V.; O’Grady, K. Mechanisms of hyperthermia in magnetic nanoparticles. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 312001.

- Deatsch, A.E.; Evans, B.A. Heating efficiency in magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 354, 163–172.

- Dennis, C.L.; Ivkov, R. Physics of heat generation using magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 715–729.

- Datta, N.R.; Ordóñez, S.G.; Gaipl, U.S.; Paulides, M.M.; Crezee, H.; Gellermann, J.; Marder, D.; Puric, E.; Bodis, S. Local hyperthermia combined with radiotherapy and-/or chemotherapy: Recent advances and promises for the future. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2015, 41, 742–753.

- Issels, R.D. Hyperthermia adds to chemotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 2546–2554.

- Orel, V.; Shevchenko, A.; Romanov, A.; Tselepi, M.; Mitrelias, T.; Barnes, C.H.W.; Burlaka, A.; Lukin, S.; Shchepotin, I. Magnetic properties and antitumor effect of nanocomplexes of iron oxide and doxorubicin. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 47–55.

- Hahn, G.M. Potential for therapy of drugs and hyperthermia. Cancer Res. 1979, 39, 2264–2268.

- Zhou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Wei, J.; Yu, C.; Kong, B.; Liu, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, W. Iron/iron oxide core/shell nanoparticles for magnetic targeting MRI and near-infrared photothermal therapy. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 7470–7478.

- Estelrich, J.; Antònia Busquets, M. Iron oxide nanoparticles in photothermal therapy. Molecules 2018, 23, 1567.

- Lee, C.W.; Wu, P.C.; Hsu, I.L.; Liu, T.M.; Chong, W.H.; Wu, C.H.; Hsieh, T.Y.; Guo, L.Z.; Tsao, Y.; Wu, P.T.; et al. New Templated Ostwald Ripening Process of Mesostructured FeOOH for Third-Harmonic Generation Bioimaging. Small 2019, 15, 1805086.

- De Paula, L.B.; Primo, F.L.; Pinto, M.R.; Morais, P.C.; Tedesco, A.C. Combination of hyperthermia and photodynamic therapy on mesenchymal stem cell line treated with chloroaluminum phthalocyanine magnetic-nanoemulsion. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 380, 372–376.

- Di Corato, R.; Béalle, G.; Kolosnjaj-Tabi, J.; Espinosa, A.; Clément, O.; Silva, A.K.A.; Ménager, C.; Wilhelm, C. Combining magnetic hyperthermia and photodynamic therapy for tumor ablation with photoresponsive magnetic liposomes. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2904–2916.

- De Paula, L.B.; Primo, F.L.; Jardim, D.R.; Morais, P.C.; Tedesco, A.C. Development, characterization, and in vitro trials of chloroaluminum phthalocyanine-magnetic nanoemulsion to hyperthermia and photodynamic therapies on glioblastoma as a biological model. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 07B307.

- Yang, K.; Wan, J.; Zhang, S.; Tian, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. The influence of surface chemistry and size of nanoscale graphene oxide on photothermal therapy of cancer using ultra-low laser power. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 2206–2214.

- Ma, X.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. PEGylated gold nanoprisms for photothermal therapy at low laser power density. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 81682–81688.

- Stern, J.M.; Kibanov Solomonov, V.V.; Sazykina, E.; Schwartz, J.A.; Gad, S.C.; Goodrich, G.P. Initial Evaluation of the Safety of Nanoshell-Directed Photothermal Therapy in the Treatment of Prostate Disease. Int. J. Toxicol. 2016, 35, 38–46.

- Winau, F.; Westphal, O.; Winau, R. Paul Ehrlich - In search of the magic bullet. Microbes Infect. 2004, 6, 786–789.

- Widder, K.; Flouret, G.; Senyei, A. Magnetic microspheres: Synthesis of a novel parenteral drug carrier. J. Pharm. Sci. 1979, 68, 79–82.

- Senyei, A.; Widder, K.; Czerlinski, G. Magnetic guidance of drug-carrying microspheres. J. Appl. Phys. 1978, 49, 3578–3583.

- Mosbach, K.; Schröder, U. Preparation and application of magnetic polymers for targeting of drugs. FEBS Lett. 1979, 102, 112–116.

- Kwon, G.S.; Okano, T. Polymeric micelles as new drug carriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1996, 21, 107–116.

- López-Dávila, V.; Seifalian, A.M.; Loizidou, M. Organic nanocarriers for cancer drug delivery. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012, 12, 414–419.

- Manatunga, D.C.; Godakanda, V.U.; de Silva, R.M.; de Silva, K.M.N. Recent developments in the use of organic–inorganic nanohybrids for drug delivery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 12, e1605.

- Zhang, R.; Olin, H. Carbon nanomaterials as drug carriers: Real time drug release investigation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2012, 32, 1247–1252.

- Lim, D.J.; Sim, M.; Oh, L.; Lim, K.; Park, H. Carbon-based drug delivery carriers for cancer therapy. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 43–52.

- Partha, R.; Conyers, J.L. Biomedical applications of functionalized fullerene-based nanomaterials. Int. J. Nanomed. 2009, 4, 261–275.

- Rasheed, A.; Kumar C.K., A.; Sravanthi, V.V.N.S.S. Cyclodextrins as drug carrier molecule: A review. Sci. Pharm. 2008, 76, 567–598.

- Kratz, F. Albumin as a drug carrier: Design of prodrugs, drug conjugates and nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 2008, 132, 171–183.

- MacDiarmid, J.A.; Brahmbhatt, H. Minicells: Versatile vectors for targeted drug or si/shRNA cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 909–916.

- Akash, M.S.H.; Rehman, K.; Parveen, A.; Ibrahim, M. Antibody-drug conjugates as drug carrier systems for bioactive agents. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2016, 65, 1–10.

- Barbé, C.; Bartlett, J.; Kong, L.; Finnie, K.; Lin, H.Q.; Larkin, M.; Calleja, S.; Bush, A.; Calleja, G. Silica particles: A novel drug-delivery system. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 1959–1966.

- Oussoren, C.; Storm, G. Liposomes to target the lymphatics by subcutaneous administration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 50, 143–156.

- Städler, B.; Price, A.D.; Zelikin, A.N. A critical look at multilayered polymer capsules in biomedicine: Drug carriers, artificial organelles, and cell mimics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 14–28.

- Kataoka, K.; Harada, A.; Nagasaki, Y. Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: Design, characterization and biological significance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 37–48.

- Moyano, D.F.; Goldsmith, M.; Solfiell, D.J.; Landesman-Milo, D.; Miranda, O.R.; Peer, D.; Rotello, V.M. Nanoparticle hydrophobicity dictates immune response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3965–3967.

- Corbo, C.; Molinaro, R.; Parodi, A.; Toledano Furman, N.E.; Salvatore, F.; Tasciotti, E. The impact of nanoparticle protein corona on cytotoxicity, immunotoxicity and target drug delivery. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 81–100.

- Jain, T.K.; Morales, M.A.; Sahoo, S.K.; Leslie-Pelecky, D.L.; Labhasetwar, V. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Sustained Delivery of Anticancer Agents. Mol. Pharm. 2005, 2, 194–205.

- Estelrich, J.; Escribano, E.; Queralt, J.; Busquets, M.A. Iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetically-guided and magnetically-responsive drug delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 8070–8101.

- Wahajuddin, S.A. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Magnetic nanoplatforms as drug carriers. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 3445–3471.

- Khalid, K.; Tan, X.; Mohd Zaid, H.F.; Tao, Y.; Lye Chew, C.; Chu, D.T.; Lam, M.K.; Ho, Y.C.; Lim, J.W.; Chin Wei, L. Advanced in developmental organic and inorganic nanomaterial: A review. Bioengineered 2020, 11, 328–355.

- Neuberger, T.; Schöpf, B.; Hofmann, H.; Hofmann, M.; Von Rechenberg, B. Superparamagnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications: Possibilities and limitations of a new drug delivery system. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 293, 483–496.

- Lockman, P.R.; Mumper, R.J.; Khan, M.A.; Allen, D.D. Nanoparticle technology for drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2002, 28, 1–13.

- Saraiva, C.; Praça, C.; Ferreira, R.; Santos, T.; Ferreira, L.; Bernardino, L. Nanoparticle-mediated brain drug delivery: Overcoming blood-brain barrier to treat neurodegenerative diseases. J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 34–47.

- Bao, Y.; Krishnan, K.M. Preparation of functionalized and gold-coated cobalt nanocrystals for biomedical applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 293, 15–19.

- Carpenter, E.E.; Sangregorio, C.; O’Connor, C.J. Effects of shell thickness on blocking temperature of nanocomposites of metal particles with gold shells. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1999, 35, 3496–3498.

- Jung, J.S.; Chae, W.S.; McIntyre, R.A.; Seip, C.T.; Wiley, J.B.; O’Connor, C.J. Preparation and characterization of Ni nanoparticles in an MCM mesoporous material. Mater. Res. Bull. 1999, 34, 1353–1360.

- Lin, X.M.; Sorensen, C.M.; Klabunde, K.J.; Hadjipanayis, G.C. Temperature Dependence of Morphology and Magnetic Properties of Cobalt Nanoparticles Prepared by an Inverse Micelle Technique. Langmuir 1998, 14, 7140–7146.

- Yano, K.; Nandwana, V.; Chaubey, G.S.; Poudyal, N.; Kang, S.; Arami, H.; Griffis, J.; Liu, J.P. Synthesis and Characterization of Magnetic FePt/Au Core/Shell Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 13088–13091.

More

Information

Subjects:

Nanoscience & Nanotechnology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.3K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

09 Jul 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No