| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Laura Gómez-Virgilio | + 2997 word(s) | 2997 | 2021-06-17 08:50:16 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2997 | 2021-07-06 05:00:40 | | |

Video Upload Options

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and the sixth cause of death in the world, constituting a major health problem for aging societies. This disease is a neurodegenerative continuum with well-established pathology hallmarks, namely the deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in extracellular plaques and intracellular hyperphosphorylated forms of the microtubule associated protein tau forming neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), accompanied by neuronal and synaptic loss. Interestingly, patients who will eventually develop AD manifest brain pathology decades before clinical symptoms appear. Among all the proposed pathogenic mechanisms to understand the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), increased oxidative stress seems to be a robust and early disease feature where many of those hypotheses converge.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and the sixth cause of death in the world, constituting a major health problem for aging societies [1]. This disease is a neurodegenerative continuum with well-established pathology hallmarks, namely the deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in extracellular plaques and intracellular hyperphosphorylated forms of the microtubule associated protein tau forming neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), accompanied by neuronal and synaptic loss [2]. Interestingly, patients who will eventually develop AD manifest brain pathology decades before clinical symptoms appear [3][4]. Nevertheless, AD is still frequently diagnosed when symptoms are highly disabling and yet there is no satisfactory treatment.

Although the manifestations of AD are preponderantly cerebral, cumulative evidence shows that AD is a systemic disorder [5]. Accordingly, molecular changes associated with AD are not exclusively manifested in the brain but include cells from different parts of the body, ranging from the blood and skin to peripheral olfactory cells. More recently, neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from AD patients have contributed to glean a more realistic insight of brain pathogenic mechanisms [6]. Alternatively, the culture of olfactory neuronal precursors (ONPs) has emerged as a relatively simpler tool to study different brain disorders, taking advantage of their neuronal lineage and their readily non-invasive isolation [7][8]. For instance, patient-derived ONPs manifest abnormal amyloid components together with tau hyperphosphorylation, which have recently led to the proposal of these cells as a novel diagnostic tool for AD [9][10][11].

Different hypotheses have attempted to explain AD pathogenesis. Some of them include Aβ cascade, tau hyperphosphorylation, mitochondrial damage, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and oxidative stress. Interestingly, although it has been difficult to establish a prevailing causative mechanism, increased levels of oxidative stress seem to be a common feature for many of these models. Furthermore, oxidative stress due to increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been broadly recognized as a very early signature during the course of AD [12][13][14]. Interestingly, AD-related oxidative stress is by no means restricted to neuronal cells but is also related to astrocytes’ oxidative damage and antioxidant capacity [15]. Indeed, since the acknowledgment of the tripartite synapse, it has become increasingly clear that different antioxidant mechanisms of astrocytes can be harnessed by synaptically active neurons and surrounding cells [16][17][18]. In the tripartite synapse, the astrocyte’s endfeet are close to synapses and can be activated by the spillover of synaptic glutamate to provide a timely antioxidant response [19][20]. Moreover, it is not entirely understood how other glial cells such as pericytes may contribute to the damage induced by AD-related oxidative stress. For instance, oxidative damage may compromise the integrity of pericytes, which in turn could alter the blood-brain barrier’s integrity, favoring the infiltration of cytotoxic cells and the emergence of brain edema [21][22]. In coherence with a broader systemic manifestation of this disease, the peripheral olfactory system shows AD-associated oxidative stress, which has been measured both in the olfactory neuroepithelium and in cultured ONPs [23][24][25]. However, while the intriguing relationship between oxidative stress and AD has been long known, their translational impact has remained limited.

2. Olfactory Neuroepithelium and the Non-Invasive Isolation of ONPs

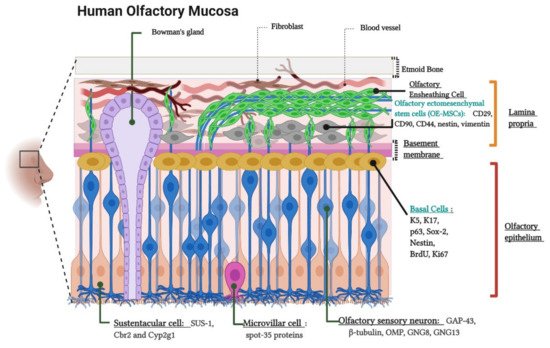

The olfactory neuroepithelium is a key structure for odor sensing. It consists of a pseudostratified columnar epithelium located on the outer domain of the olfactory mucosa settled on the basement membrane (BM) and the lamina propria (LP) [26]. The cellular composition of these layers has been widely documented based on morphological analysis and the use of characteristic markers for each cell type [27][28][29][30]. Figure 1 schematizes the location, cellular components, and molecular markers of the human olfactory mucosa.

Figure 1. Cytoarchitecture and cellular components of the human olfactory mucosa. Lamina propria components. Olfactory Ensheathing Cells, Bowman’s gland and Olfactory Ectomesenchymal Stem Cells (OE-MSCs). The image indicates the OE-MSCs markers: CD29, CD90, CD44, Nestin, and Vimentin. Olfactory epithelium components. Basal Cells, Olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) or Olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs), Sustentacular cells, and Microvillar cells. The figure shows basal cell markers: K5 (Keratin 5), K17 (Keratin 17), p63, Sox-2 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 2), Nestin, BrdU (Bromodeoxyuridine), and Ki-67; ORNs markers: GAP-43 (Growth Associated Protein 43), β-tubulin, OMP (Olfactory Marker Protein), GNG8 (Guanine Nucleotide-binding protein subunit Gamma), and GNG13 (Guanine Nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(O) subunit Gamma-13)); sustentacular cell markers (SUS-1, Cbr2 (Carbonyl Reductase 2) and Cyp2g1 (Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily G, polypeptide 1)) and, microvillar cell marker: (spot-35 proteins). Created with BioRender.com.

The olfactory neuroepithelium is also a source of stem cells, which are capable of self-renewal and can generate neuronal precursors throughout the entire human lifetime. These precursors include neural stem cells known as basal cells. As expected for neural stem cells, basal cells are multipotent and allow the continuous replacement of neuronal and non-neuronal cells such as olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) and sustentacular cells (of astrocytic lineage), respectively [31][32][33]. In addition, the LP contains another less accessible population of stem cells, whose features meet most of the minimum criteria of the mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy [34]. As such, they are named as olfactory ectomesenchymal stem cells (OE-MSCs) [35][36][37].

Isolation of cells of the olfactory neuroepithelium from patients provides a source of cultured neural stem cells, which has been used to model different brain disorders such as schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, autism, ataxia-telangiectasia, hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), and AD [7][38][39][40][41][42]. These neural stem cells can be frozen and stored for subsequent use and tolerate several passages without significantly losing their main properties. Furthermore, purified cultures obtained by cloning selection through limiting dilution significantly increases cell viability at least until passage 60 [43]. In this work, we will refer to neural stem cells isolated from the olfactory neuroepithelium as olfactory neuronal precursors (ONPs), similar to [8][9][43][44].

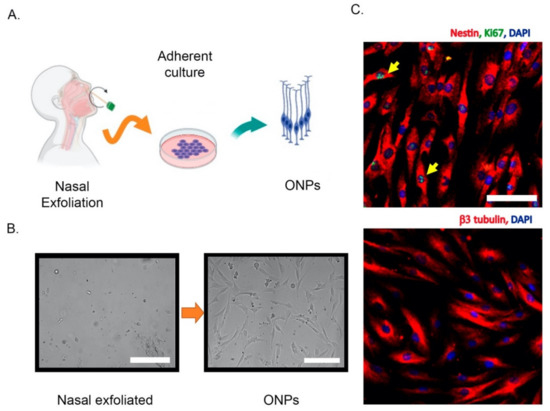

Different strategies have been used to isolate and culture patient-derived ONPs, ranging from biopsies to non-invasive exfoliation of the nasal turbinate. Human ONPs were first isolated by Wolozin et al. from the olfactory neuroepithelium of cadavers or from adult biopsied samples [10][45]. Another similar isolation approach demonstrated that a significant subpopulation of these cells express markers of mature olfactory neurons such as OMP, Golf, NCAM, and NST and look small and bright to the microscope, in contrast to the remaining “dark phase” cells that do not express OMP, but glial markers [46]. However, a systematic characterization of these cultures has shown that after a few days in vitro, both dark and bright phase cells show an intracellular calcium increase in response to odorants, highlighting the neuronal features of these cells [47]. In addition, cells with features of ONPs have also been obtained from dissociated neurospheres, which have been denominated “olfactory neurosphere-derived” (ONS) cells [36]. Alternatively, ONPs can be non-invasively isolated by an exfoliation of the nasal cavity [44]. These exfoliated cells can be cultured in a modified media to propitiate neural lineage maintenance and proliferation. Notably, these neuronal precursors conserve their capability to differentiate into ORNs in the presence of dibutyryl adenosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate (Db-cAMP) and, strikingly, maintain their electrical response to odorants [44]. Thus, non-invasively isolated ONPs retain neuronal features similar to those obtained by biopsy. A simplified extraction protocol and the molecular characterization of non-invasively isolated ONPs is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Non-invasive isolation of olfactory neuronal precursors (ONPs). (A) Schematic cartoon of the isolation protocol based on the extraction of nasal exfoliate with the subsequent adherent culture and enrichment of ONPs. (B) Left, the nasal exfoliate is directly seeded on adherent plates, showing a mixture of cell morphologies. Right, after 1–2 weeks ONPs dividing colonies are easily observed with their characteristic morphologies. (C) Upper panel, immunofluorescence of cultured ONPs, depicting the stem cell marker Nestin and Ki67 (yellow arrows) to show active cell proliferation. Lower panel, cultured ONPs express neuronal markers such as β3 tubulin. Cell nuclei are shown by DAPI staining. All scale bars = 100 μm. All images were generated in our lab. Created with BioRender.com.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Oxidative Stress in the Olfactory Epithelium and ONPs

Oxidative stress is the result of an imbalance between oxidant and antioxidant cellular pathways. One of the most studied oxidant compounds are ROS, which are highly reactive molecules, including peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion radical (O2 • −), and hydroxyl radical (• OH), among others. These molecules may covalently interact with lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates, generating molecular adducts and cumulative damage that, when sensed by cells, may actively trigger different death programs [48].

It was well established almost three decades ago that oxidative stress damage is linked to AD [14]. Furthermore, it has been proposed that oxidative stress at different brain neuronal and non-neuronal cells might be the earliest event of a pathogenic cascade [13]. Whether oxidative stress is a causative agent or just a consequence in neurodegenerative disorders has been thoroughly debated for several years, but still remains an open question [49][50][51]. The most parsimonious interpretation of this evidence is that oxidative stress as well as other potential AD causative agents (such as Aβ accumulation) are part of a highly interconnected vicious cycle rather than a linear chain of events with a unique origin. The molecular mechanisms and implications of oxidative stress on the nervous system and, potentially, during AD pathogenesis have been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere [12][52]. Here, we focus on evidence showing AD-associated oxidative stress in the peripheral olfactory system rather than reviewing mechanistic explanations.

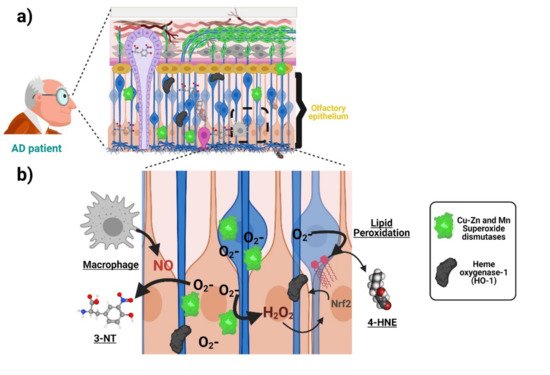

Oxidative stress associated with AD is manifested in the olfactory neuroepithelium. Accordingly, increased immunoreactivity of the antioxidant enzyme manganese and Copper-Zinc superoxide dismutases have been detected in ORNs and basal and sustentacular cells of the olfactory neuroepithelium of AD patients compared with age-matched controls [53]. Analogously, AD patients harbor a higher immunoreactivity against the antioxidant protein Metallothionein both in the olfactory neuroepithelium and the Bowman’s Glands and the LP [54]. Both results suggest that cells from olfactory neuroepithelium elicit an increased antioxidant defense, due to increased oxidative stress during AD. With respect to the direct measurement of oxidation products, post-mortem staining showed an increase in 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) in the brain and olfactory neuroepithelium of AD patients [23]. Figure 3 schematizes the antioxidant response and oxidative damage reported in ONPs and OE from AD patients. It would be of interest to uncover whether some AD genetic factors such as the ApoE ε4 allele (ApoE4) (the single most important genetic risk factor for AD) also manifests oxidative stress signatures in the olfactory epithelium. It is plausible that this is the case because deficits in odor fluency, identification, recognition memory, and odor threshold sensitivity have been associated with the inheritance of the ApoE4 genotype in several studies [55][56][57]. For a more thorough compiling of evidence showing AD-associated oxidative damage across other domains of the nervous system, readers may refer to the following excellent articles [12][52][58].

Figure 3. Oxidative stress associated with AD in the olfactory neuroepithelium. (a) ONPs and sustentacular cells in the olfactory epithelium (OE) show an increased antioxidant defense with elevated levels of manganese and copper-zinc superoxide dismutases as well as heme oxygenase-1 due to increased oxidative stress in AD patients compared with age-matched controls. Moreover, there is an increase in 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) and 4-hydroxynonenal (lipid peroxidation indicator) levels, suggesting AD-associated oxidative damage. (b) The increased generation of superoxide anion activates superoxide dismutases (SOD) as an antioxidant response. The generation of other reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as H2O2, induces the expression of other antioxidant enzymes (heme oxygenase-1). On the other hand, the accumulation of superoxide anion increases the levels of compounds such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE). Moreover, the increased levels of 3-NT are produced from the interaction of superoxide anion and nitric oxide (NO), whose probable source is located at activated macrophages in the OE of AD patients. Created with BioRender.com.

The relationship between oxidative stress and AD has been extensively studied mainly through cellular and animal models [40][47]. However, these models may not fully capture key features of the disease. This limitation potentially leads to wrong conclusions about the pathogenic mechanisms and ultimately may dampen the development of effective therapies. Alternatively, patient-derived cells of neuronal lineage such as those from the olfactory epithelium may provide a convenient solution to this problem [5][9][35].

Interestingly, cultured patient-derived ONPs and other peripheral cells also manifest AD-associated oxidative stress. For example, an increase in the level of hydroxynonenal and Nɛ-(carboxymethyl)lysine) (indicating lipid peroxidation), as well as a higher content of heme oxygenase-1, has been found in ONPs isolated from AD patients compared with age-matched controls (Figure 3) [24]. Furthermore, ONPs from AD patients are also more susceptible to oxidative stress-induced cell death [25]. This is strikingly similar to what has been found by our group in blood-derived lymphocytes from AD patients [59][60]. Indeed, manifestations of oxidative stress associated with AD have been reported in different patient-derived peripheral cells ranging from blood cells to fibroblasts and iPSCs-derived neurons. These changes may include compensatory antioxidant responses and a rise in the concentration of oxidation by-products, as well as increased susceptibility to ROS-induced cell death, which has been demonstrated in different cellular types from AD patients. Many of those findings are summarized in the Table 1. In addition, Table 1 also summarizes similar evidence of other relevant pathogenic mechanisms proposed for AD pathogenesis, including Amyloid/Tau, mitochondria, and ER-stress. Thus, different cells throughout the body show signs of different proposed AD pathogenic mechanisms, including oxidative stress at early stages of the disease continuum. The robustness of this tendency highlights the potential of patient-derived cells, and in particular ONPs, for monitoring oxidative stress associated with AD.

Table 1. Signatures of oxidative stress and other AD mechanistic hypotheses are manifested in patient-derived peripheral cells, iPSCs and ONPs.

| Pathogenic Mechanism | Main Finding | Cellular Type | Lineage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid/Tau | Platelets from AD patients reproduce the increased amyloidogenic processing of AβPP | Platelets | Non-neuronal | [61] |

| Amyloid/Tau | AD platelets harbor increased levels of a higher molecular weight tau isoform | Platelets | Non-neuronal | [62] |

| Amyloid/Tau | Alteration of AβPP, BACE, and ADAM 10 levels in early stages of the disease | Platelets | Non-neuronal | [63][64][65] |

| Amyloid/Tau | It is suggested a decreased non-amyloidogenic processing of AβPP by a lack of nicastrin mRNA expression in samples obtained from AD patients | Lymphocytes | Non-neuronal | [66] |

| Amyloid/Tau | Altered balance between Aβ-oligomers and PKCε levels in AD. Loss of PKCε-mediated inhibition of Aβ |

Fibroblasts | Non-neuronal | [67] |

| Amyloid/Tau | Higher Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio compared to control cells | PSEN1 iPSC-derived neural progenitors |

Neuronal | [68] |

| Amyloid/Tau | Mutation alters the initial cleavage site of γ-secretase, resulting in an increased generation of Aβ42, in addition to an increase in the levels of total and phosphorylated tau | Neuron-derived iPSCs from patients harboring the London FAD AβPP mutation V717I |

Neuronal | [69] |

| Amyloid/Tau | Oligomeric forms of canonical Aβ impairs synaptic plasticity |

Cortical neurons from three genetic forms of AD —PSEN1 L113_I114insT, AβPP duplication (AβPPDp), and Ts21— generated from iPSCs | Neuronal | [70] |

| Amyloid/Tau | Increase in the content and changes in the subcellular distribution of t-tau and p-tau in cells from AD patients compared to controls | Non-invasively isolated ONPs | Neuronal | [9] |

| Mitochondria | Compromise of mitochondrial COX from AD patients |

Platelets | Non-neuronal | [71] |

| Mitochondria | Platelets isolated from AD patients show decreased ATP levels | Platelets | Non-neuronal | [72] |

| Mitochondria | AD lymphocytes exhibit impairment of total OXPHOS capacity | Lymphocytes | Non-neuronal | [73] |

| Mitochondria | AD skin fibroblasts show increased production of CO2 and reduced oxygen uptake suggesting that mitochondrial electron transport chain might be compromised |

Fibroblasts | Non-neuronal | [74] |

| Mitochondria | AD fibroblasts present reduction in mitochondrial length and a dysfunctional mitochondrial bioenergetics profile | Fibroblasts | Non-neuronal | [75] |

| Mitochondria | SAD fibroblasts exhibit aged mitochondria, and their recycling process is impaired | Fibroblasts | Non-neuronal | [76] |

| Mitochondria | Patient-derived cells show increased levels of oxidative phosphorylation chain complexes | Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neuronal cells (iN cells) from SAD patients |

Neuronal | [77] |

| Mitochondria | Mitophagy failure as a consequence of lysosomal dysfunction |

iPSC-derived neurons from FAD1 patients harboring PSEN1 A246E mutation | Neuronal | [78] |

| Mitochondria | Neurons exhibit defective mitochondrial axonal transport |

iPSC-derived neurons from an AD patient carrying AβPP -V715M mutation | Neuronal | [79] |

| Oxidative Stress | Increased activity of the antioxidant enzyme catalase in probable AD patients | Erythrocytes | Non-neuronal | [80] |

| Oxidative Stress | Increased production and content of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) |

Erythrocytes and Platelets | Non-neuronal | [81] |

| Oxidative Stress | Increase in the content of the unfolded version of p53 as well as reduced SOD activity | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) | Non-neuronal | [82] |

| Oxidative Stress | Exacerbated response to NFKB pathway | PBMCs | Non-neuronal | [83] |

| Oxidative Stress | Increased ROS production in response to H2O2 | PBMCs | Non-neuronal | [59] |

| Oxidative Stress | AD lymphocytes were more prone to cell death after a H2O2 challenge | Lymphocytes | Non-neuronal | [84] |

| Oxidative Stress | Reduced antioxidant capacity of FAD lymphocytes and fibroblasts together with increased lipid peroxidation on their plasma membrane | Lymphocytes and Fibroblasts | Non-neuronal | [85] |

| Oxidative Stress | Aβ peptides were better internalized and generated greater oxidative damage in FAD fibroblasts | Fibroblasts | Non-neuronal | [86] |

| Oxidative Stress | Aβ peptide caused a higher increase in the oxidation of HSP60 | Fibroblasts | Non-neuronal | [87] |

| Oxidative Stress | Reduction in the levels of Vimentin in samples from AD patients | iPSCs-derived neurons from AD patient | Neuronal | [58] |

| Oxidative Stress | Increased levels of hydroxynonenal, Nɛ-(carboxymethyl)lysine), and heme oxygenase-1 in samples from AD patients | Biopsy-derived ONPs | Neuronal | [24] |

| Oxidative Stress | Increased susceptibility to oxidative-stress-induced cell death | Biopsy-derived ONPs | Neuronal | [25] |

| ER-Stress | Impaired ER Ca2+ and ER stress in PBMCs from MCIs and mild AD patients | PBMCs | Non-neuronal | [88] |

| ER-Stress | Accumulation of Aβ oligomers induced ER and oxidative stress | iPSC-derived neural cells from a patient carrying APP-E693Δ mutation and a sporadic AD patient | Neuronal | [89] |

| ER-Stress | Aβ-S8C dimer triggers an ER stress response more prominent in AD neuronal cultures where several genes from the UPR were upregulated | iPSC-derived neuronal cultures carrying the AD-associated TREM2 R47H variant | Neuronal | [90] |

| ER-Stress | Accumulation of Aβ oligomers in iPSC-derived neurons from AD patients leads to increased ER stress |

iPSC-derived neurons from patients with an AβPP-E693Δ mutation | Neuronal | [91] |

References

- Haque, R.U.; Levey, A.I.; Alzheimer’s disease: A clinical perspective and future nonhuman primate research opportunities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2019, 116 (52), 26224-26229, 10.1073/pnas.1912954116.

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Hyman, B.T.; Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2011, 1, a006189, 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189.

- Perrin, R.J.; Fagan, A.M.; Holtzman, D.M.; Multimodal techniques for diagnosis and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2009, 461, 916–922, 10.1038/nature08538.

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Knopman, D.S.; Jagust, W.J.; Shaw, L.M.; Aisen, P.S.; Weiner, M.W.; Petersen, R.C.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. The Lancet. Neurology 2010, 9, 119–128, 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6.

- Trushina, E.; Alzheimer’s disease mechanisms in peripheral cells: Promises and challenges. Alzheimer’s & dementia 2019, 5, 652–660, 10.1016/j.trci.2019.06.008..

- Penney, J.; Ralvenius, W.T.; Tsai, L.H.; Modeling Alzheimer’s disease with iPSC-derived brain cells. Molecular psychiatry 2020, 25, 148–167, 10.1038/s41380-019-0468-3.

- Mackay-Sim, A; Concise review: Patient-derived olfactory stem cells: New models for brain diseases. Stem cells 2012, 30, 2361–2365, 10.1002/stem.1220.

- Jimenez-Vaca, A.L.; Benitez-King, G.; Ruiz, V.; Ramirez-Rodriguez, G.B.; Hernandez-de la Cruz, B.; Salamanca-Gomez, F.A.; Gonzalez-Marquez, H.; Ramirez-Sanchez, I.; Ortiz-Lopez, L.; Velez-Del Valle, C.; et al.et al. Exfoliated Human Olfactory Neuroepithelium: A Source of Neural Progenitor Cells. Molecular neurobiology 2018, 55, 2516–2523, 10.1007/s12035-017-0500-z.

- Riquelme, A.; Valdes-Tovar, M.; Ugalde, O.; Maya-Ampudia, V.; Fernandez, M.; Mendoza-Duran, L.; Rodriguez-Cardenas, L.; Benitez-King, G.; Potential Use of Exfoliated and Cultured Olfactory Neuronal Precursors for In Vivo Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis: A Pilot Study. Cellular and molecular neurobiology 2020, 40, 87–98, 10.1007/s10571-019-00718-z.

- Wolozin, B.; Zheng, B.; Loren, D.; Lesch, K.P.; Lebovics, R.S.; Lieberburg, I.; Sunderland, T.; Beta/A4 domain of APP: Antigenic differences between cell lines. Journal of neuroscience research 1992, 33, 189–195, 10.1002/jnr.490330202.

- Wolozin, B.; Bacic, M.; Merrill, M.J.; Lesch, K.P.; Chen, C.; Lebovics, R.S.; Sunderland, T.; Differential expression of carboxyl terminal derivatives of amyloid precursor protein among cell lines. Journal of neuroscience research 1992, 33, 163–169, 10.1002/jnr.490330121.

- Butterfield, D.A.; Halliwell, B.; Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 2019, 20, 148–160, 10.1038/s41583-019-0132-6.

- Nunomura, A.; Perry, G.; Aliev, G.; Hirai, K.; Takeda, A.; Balraj, E.K.; Jones, P.K.; Ghanbari, H.; Wataya, T.; Shimohama, S.; et al.et al. Oxidative damage is the earliest event in Alzheimer disease. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology 2001, 60, 759–767, 10.1093/jnen/60.8.759.

- Smith, M.A.; Nunomura, A.; Lee, H.G.; Zhu, X.; Moreira, P.I.; Avila, J.; Perry, G.; Chronological primacy of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of aging 2005, 26, 579–580, 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.021.

- Gonzalez-Reyes, R.E.; Nava-Mesa, M.O.; Vargas-Sanchez, K.; Ariza-Salamanca, D.; Mora-Munoz, L.; Involvement of Astrocytes in Alzheimer’s Disease from a Neuroinflammatory and Oxidative Stress Perspective. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2017, 10, 427, 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00427.

- Habas, A.; Hahn, J.; Wang, X.; Margeta, M.; Neuronal activity regulates astrocytic Nrf2 signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013, 110, 18291–18296, 10.1073/pnas.1208764110.

- Qiu, J.; Dando, O.; Febery, J.A.; Fowler, J.H.; Chandran, S.; Hardingham, G.E.; Neuronal Activity and Its Role in Controlling Antioxidant Genes. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 1933, 10.3390/ijms21061933.

- Baxter, P.S.; Hardingham, G.E.; Adaptive regulation of the brain’s antioxidant defences by neurons and astrocytes. Free radical biology & medicine 2016, 100, 147–152, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.027.

- Araque, A.; Parpura, V.; Sanzgiri, R.P.; Haydon, P.G.; Tripartite synapses: Glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends in neurosciences 1999, 22, 208–215, 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01349-6.

- Perea, G.; Navarrete, M.; Araque, A.; Tripartite synapses: Astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends in neurosciences 2009, 32, 421–431, 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.001.

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Shimony, J.S.; Owen, C.J.; Liu, J.; Fagan, A.M.; Cairns, N.J.; Ances, B.; Morris, J.C.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; et al. IC-P-172: Simultaneous Quantification of White Matter Abnormalities and Vasogenic Edema in Early Alzheimer Disease.. Alzheimer’s & dementia 2016, 12, P125-P126, 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.203.

- Kitchen, P.; Salman, M.M.; Halsey, A.M.; Clarke-Bland, C.; MacDonald, J.A.; Ishida, H.; Vogel, H.J.; Almutiri, S.; Logan, A.; Kreida, S.; et al.et al. Targeting Aquaporin-4 Subcellular Localization to Treat Central Nervous System Edema. Cell 2020, 181, 784–799 e719, 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.037.

- Getchell, M.L.; Shah, D.S.; Buch, S.K.; Davis, D.G.; Getchell, T.V; 3-Nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity in olfactory receptor neurons of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for impaired odor sensitivity. . Neurobiology of aging 2003, 24, 663–673, 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00195-1.

- Ghanbari, H.A.; Ghanbari, K.; Harris, P.L.; Jones, P.K.; Kubat, Z.; Castellani, R.J.; Wolozin, B.L.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; Oxidative damage in cultured human olfactory neurons from Alzheimer’s disease patients. Aging cell 2004, 3, 41–44, 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00083.x.

- Nelson, V.M.; Dancik, C.M.; Pan, W.; Jiang, Z.G.; Lebowitz, M.S.; Ghanbari, H.A.; PAN-811 inhibits oxidative stress-induced cell death of human Alzheimer’s disease-derived and age-matched olfactory neuroep-ithelial cells via suppression of intracellular reactive oxygen species. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2009, 17, 611–619, 10.3233/JAD-2009-1078.

- Jafek, B.W.; Ultrastructure of human nasal mucosa. The Laryngoscope 1983, 93, 1576–1599, 10.1288/00005537-198312000-00011.

- Moran, D.T.; Rowley, J.C., 3rd; Jafek, B.W.; Lovell, M.A.; The fine structure of the olfactory mucosa in man. Journal of neurocytology 1982, 11, 721–746, 10.1007/bf01153516.

- Morrison, E.E.; Costanzo, R.M.; Morphology of the human olfactory epithelium. The Journal of comparative neurology 1990, 297, 1–13, 10.1002/cne.902970102.

- Verhaagen, J.; Oestreicher, A.B.; Gispen, W.H.; Margolis, F.L.; The expression of the growth associated protein B50/GAP43 in the olfactory system of neonatal and adult rats. The Journal of Neuroscience : The official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 1989, 9, 683–691, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-02-00683.1989.

- Holbrook, E.H.; Wu, E.; Curry, W.T.; Lin, D.T.; Schwob, J.E.; Immunohistochemical characterization of human olfactory tissue.. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 1687–1701, 10.1002/lary.21856..

- Fletcher, R.B.; Das, D.; Gadye, L.; Street, K.N.; Baudhuin, A.; Wagner, A.; Cole, M.B.; Flores, Q.; Choi, Y.G.; Yosef, N.; et al.et al. Deconstructing Olfactory Stem Cell Trajectories at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell stem cell 2017, 20, 817–830 e818, 10.1016/j.stem.2017.04.003.

- Hahn, C.G.; Han, L.Y.; Rawson, N.E.; Mirza, N.; Borgmann-Winter, K.; Lenox, R.H.; Arnold, S.E.; In vivo and in vitro neurogenesis in human olfactory epithelium. The Journal of comparative neurology 2005, 483, 154–163, 10.1002/cne.20424.

- Chen, X.; Fang, H.; Schwob, J.E.; Multipotency of purified, transplanted globose basal cells in olfactory epithelium. The Journal of comparative neurology 2004, 469, 457–474, 10.1002/cne.11031.

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E.; et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317, 10.1080/14653240600855905.

- Delorme, B.; Nivet, E.; Gaillard, J.; Haupl, T.; Ringe, J.; Deveze, A.; Magnan, J.; Sohier, J.; Khrestchatisky, M.; Roman, F.S.; et al.et al. The human nose harbors a niche of olfactory ectomesenchymal stem cells displaying neurogenic and osteogenic properties. Stem cells and development 2010, 19, 853–866, 10.1089/scd.2009.0267.

- Murrell, W.; Feron, F.; Wetzig, A.; Cameron, N.; Splatt, K.; Bellette, B.; Bianco, J.; Perry, C.; Lee, G.; Mackay-Sim, A.; et al. Multipotent stem cells from adult olfactory mucosa. Developmental dynamics: An official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2005, 233, 496–515, 10.1002/dvdy.20360.

- Tanos, T.; Saibene, A.M.; Pipolo, C.; Battaglia, P.; Felisati, G.; Rubio, A.; Isolation of putative stem cells present in human adult olfactory mucosa. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181151, 10.1371/journal.pone.0181151.

- Matigian, N.; Abrahamsen, G.; Sutharsan, R.; Cook, A.L.; Vitale, A.M.; Nouwens, A.; Bellette, B.; An, J.; Anderson, M.; Beckhouse, A.G.; et al.et al. Disease-specific, neurosphere-derived cells as models for brain disorders. Disease models & mechanisms 2010, 3, 785–798, 10.1242/dmm.005447.

- Feron, F.; Gepner, B.; Lacassagne, E.; Stephan, D.; Mesnage, B.; Blanchard, M.P.; Boulanger, N.; Tardif, C.; Deveze, A.; Rousseau, S.; et al.et al. Olfactory stem cells reveal MOCOS as a new player in autism spectrum disorders. Molecular psychiatry 2016, 21, 1215–1224, 10.1038/mp.2015.106.

- Stewart, R.; Wali, G.; Perry, C.; Lavin, M.F.; Feron, F.; Mackay-Sim, A.; Sutharsan, R.; A Patient-Specific Stem Cell Model to Investigate the Neurological Phenotype Observed in Ataxia-Telangiectasia. Methods in molecular biology 2017, 1599, 391–400, 10.1007/978-1-4939-6955-5_28.

- Fan, Y.; Wali, G.; Sutharsan, R.; Bellette, B.; Crane, D.I.; Sue, C.M.; Mackay-Sim, A.; Low dose tubulin-binding drugs rescue peroxisome trafficking deficit in patient-derived stem cells in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia. Biology open 2014, 3, 494–502, 10.1242/bio.20147641.

- Ayala-Grosso, C.A.; Pieruzzini, R.; Diaz-Solano, D.; Wittig, O.; Abrante, L.; Vargas, L.; Cardier, J.; Amyloid-abeta Peptide in olfactory mucosa and mesenchymal stromal cells of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Brain pathology 2015, 25, 136–145, 10.1111/bpa.12169.

- Solis-Chagoyan, H.; Flores-Soto, E.; Valdes-Tovar, M.; Cercos, M.G.; Calixto, E.; Montano, L.M.; Barajas-Lopez, C.; Sommer, B.; Aquino-Galvez, A.; Trueta, C.; et al.et al. Purinergic Signaling Pathway in Human Olfactory Neuronal Precursor Cells. Stem cells international 2019, 2019, 2728786, 10.1155/2019/2728786.

- Benitez-King, G.; Riquelme, A.; Ortiz-Lopez, L.; Berlanga, C.; Rodriguez-Verdugo, M.S.; Romo, F.; Calixto, E.; Solis-Chagoyan, H.; Jimenez, M.; Montano, L.M.; et al.et al A non-invasive method to isolate the neuronal linage from the nasal epithelium from schizophrenic and bipolar diseases.. Journal of neuroscience methods 2011, 201, 35–45, 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.07.009.

- Wolozin, B.; Sunderland, T.; Zheng, B.B.; Resau, J.; Dufy, B.; Barker, J.; Swerdlow, R.; Coon, H.; Continuous culture of neuronal cells from adult human olfactory epithelium. Journal of molecular neuroscience: MN 1992, 3, 137–146, 10.1007/bf02919405.

- Gomez, G.; Rawson, N.E.; Hahn, C.G.; Michaels, R.; Restrepo, D.; Characteristics of odorant elicited calcium changes in cultured human olfactory neurons. Journal of neuroscience research 2000, 62, 737–749, 10.1002/1097-4547(20001201)62:5<737::AID-JNR14>3.0.CO;2-A.

- Yazinski, S.; Gomez, G.; Time course of structural and functional maturation of human olfactory epithelial cells in vitro. Journal of neuroscience research 2014, 92, 64–73, 10.1002/jnr.23296.

- Kagan, V.E.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Sun, W.Y.; Vlasova, II.; Dar, H.; Tyurin, V.A.; Amoscato, A.A.; Mallampalli, R.; van der Wel, P.C.A.; He, R.R.; et al.et al. Redox phospholipidomics of enzymatically generated oxygenated phospholipids as specific signals of programmed cell death. Free radical biology & medicine 2020, 147, 231–241, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.12.028.

- Andersen, J.K.; Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: Cause or consequence? . Nature medicine 2004, 10 Suppl, S18-25, 10.1038/nrn1434.

- Sutherland, G.T.; Chami, B.; Youssef, P.; Witting, P.K.; Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease: Primary villain or physiological by-product?. Redox report: Communications in free radical research 2013, 18, 134–141, 10.1179/1351000213Y.0000000052.

- Butterfield, D.A.; Boyd-Kimball, D; Oxidative Stress, Amyloid-beta Peptide, and Altered Key Molecular Pathways in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 2018, 62, 1345–1367, 10.3233/JAD-170543.

- Tonnies, E.; Trushina, E.; Oxidative Stress, Synaptic Dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 2017, 57, 1105–1121, 10.3233/JAD-161088.

- Kulkarni-Narla, A.; Getchell, T.V.; Schmitt, F.A.; Getchell, M.L.; Manganese and copper-zinc superoxide dismutases in the human olfactory mucosa: Increased immunoreactivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Experimental neurology 1996, 140, 115–125, 10.1006/exnr.1996.0122.

- Chuah, M.I.; Getchell, M.L.; Metallothionein in olfactory mucosa of Alzheimer’s disease patients and apoE-deficient mice. Neuroreport 1999, 10, 1919–1924, 10.1097/00001756-199906230-00023.

- Calhoun-Haney, R.; Murphy, C.; Apolipoprotein epsilon4 is associated with more rapid decline in odor identification than in odor threshold or Dementia Rating Scale scores. Brain and cognition 2005, 58, 178–182, 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.10.004.

- Gilbert, P.E.; Murphy, C.; The effect of the ApoE epsilon4 allele on recognition memory for olfactory and visual stimuli in patients with pathologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease, probable Alzheimer’s disease, and healthy elderly controls. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology 2004, 26, 779–794, 10.1080/13803390490509439.

- Wang, Q.S.; Tian, L.; Huang, Y.L.; Qin, S.; He, L.Q.; Zhou, J.N.; Olfactory identification and apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele in mild cognitive impairment. Brain research 2002, 951, 77–81, 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03137-2.

- Chen, M.; Lee, H.K.; Moo, L.; Hanlon, E.; Stein, T.; Xia, W.; Common proteomic profiles of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived three-dimensional neurons and brain tissue from Alzheimer patients. Journal of proteomics 2018, 182, 21–33, 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.04.032.

- Ponce, D.P.; Salech, F.; SanMartin, C.D.; Silva, M.; Xiong, C.; Roe, C.M.; Henriquez, M.; Quest, A.F.; Behrens, M.I.; Increased susceptibility to oxidative death of lymphocytes from Alzheimer patients correlates with dementia severity. Current Alzheimer research 2014, 11, 892–898, 10.2174/1567205011666141001113135.

- Salech, F.; Ponce, D.P.; SanMartin, C.D.; Rogers, N.K.; Chacon, C.; Henriquez, M.; Behrens, M.I.; PARP-1 and p53 Regulate the Increased Susceptibility to Oxidative Death of Lymphocytes from MCI and AD Patients. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2017, 9, 310, 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00310.

- Tang, K.; Hynan, L.S.; Baskin, F.; Rosenberg, R.N.; Platelet amyloid precursor protein processing: A bio-marker for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the neurological sciences 2006, 240, 53–58, 10.1016/j.jns.2005.09.002.

- Neumann, K.; Farias, G.; Slachevsky, A.; Perez, P.; Maccioni, R.B.; Human platelets tau: A potential peripheral marker for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 2011, 25, 103–109, 10.3233/JAD-2011-101641.

- Colciaghi, F.; Marcello, E.; Borroni, B.; Zimmermann, M.; Caltagirone, C.; Cattabeni, F.; Padovani, A.; Di Luca, M.; Platelet APP, ADAM 10 and BACE alterations in the early stages of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2004, 62, 498–501, 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106953.49802.9c.

- Colciaghi, F.; Borroni, B.; Pastorino, L.; Marcello, E.; Zimmermann, M.; Cattabeni, F.; Padovani, A.; Di Luca, M.; [alpha]-Secretase ADAM10 as well as [alpha]APPs is reduced in platelets and CSF of Alzheimer disease patients. Molecular medicine 2002, 8, 67–74, 10.1007/BF03402076.

- Vignini, A.; Sartini, D.; Morganti, S.; Nanetti, L.; Luzzi, S.; Provinciali, L.; Mazzanti, L.; Emanuelli, M.; Platelet amyloid precursor protein isoform expression in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for peripheral marker. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology 2011, 24, 529–534, 10.1177/039463201102400229.

- Herrera-Rivero, M.; Soto-Cid, A.; Hernandez, M.E.; Aranda-Abreu, G.E; Tau, APP, NCT and BACE1 in lymphocytes through cognitively normal ageing and neuropathology. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias 2013, 85, 1489–1496, 10.1590/0001-376520130013.

- Khan, T.K.; Sen, A.; Hongpaisan, J.; Lim, C.S.; Nelson, T.J.; Alkon, D.L.; PKCepsilon deficits in Alzheimer’s disease brains and skin fibroblasts. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 2015, 43, 491–509, 10.3233/JAD-141221.

- Sproul, A.A.; Jacob, S.; Pre, D.; Kim, S.H.; Nestor, M.W.; Navarro-Sobrino, M.; Santa-Maria, I.; Zimmer, M.; Aubry, S.; Steele, J.W.; et al.et al. Characterization and molecular profiling of PSEN1 familial Alzheimer’s disease iPSC-derived neural progenitors. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84547, 10.1371/journal.pone.0084547.

- Muratore, C.R.; Rice, H.C.; Srikanth, P.; Callahan, D.G.; Shin, T.; Benjamin, L.N.; Walsh, D.M.; Selkoe, D.J.; Young-Pearse, T.L.; The familial Alzheimer’s disease APPV717I mutation alters APP processing and Tau expression in iPSC-derived neurons. Human molecular genetics 2014, 23, 3523–3536, 10.1093/hmg/ddu064.

- Hu, N.W.; Corbett, G.T.; Moore, S.; Klyubin, I.; O’Malley, T.T.; Walsh, D.M.; Livesey, F.J.; Rowan, M.J.; Extracellular Forms of Abeta and Tau from iPSC Models of Alzheimer’s Disease Disrupt Synaptic Plasticity.. Cell reports 2018, 23, 1932–1938, 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.040.

- Bosetti, F.; Brizzi, F.; Barogi, S.; Mancuso, M.; Siciliano, G.; Tendi, E.A.; Murri, L.; Rapoport, S.I.; Solaini, G.; Cytochrome c oxidase and mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase (ATP synthase) activities in platelets and brain from patients with Alz-heimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 2002, 23, 371–376, 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00314-1.

- Cardoso, S.M.; Proenca, M.T.; Santos, S.; Santana, I.; Oliveira, C.R.; Cytochrome c oxidase is decreased in Alzheimer’s disease platelets. Neurobiology of aging 2004, 25, 105–110, 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00033-2.

- Leuner, K.; Schulz, K.; Schutt, T.; Pantel, J.; Prvulovic, D.; Rhein, V.; Savaskan, E.; Czech, C.; Eckert, A.; Muller, W.E.; et al. Peripheral mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Focus on lymphocytes. Molecular neurobiology 2012, 46, 194–204, 10.1007/s12035-012-8300-y.

- Sims, N.R.; Finegan, J.M.; Blass, J.P.; Altered metabolic properties of cultured skin fibroblasts in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of neurology 1987, 21, 451–457, 10.1002/ana.410210507.

- Perez, M.J.; Ponce, D.P.; Osorio-Fuentealba, C.; Behrens, M.I.; Quintanilla, R.A.; Mitochondrial Bioenergetics Is Altered in Fibroblasts from Patients with Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Frontiers in neuroscience 2017, 11, 553, 10.3389/fnins.2017.00553.

- Martin-Maestro, P.; Gargini, R.; Garcia, E.; Perry, G.; Avila, J.; Garcia-Escudero, V.; Slower Dynamics and Aged Mitochondria in Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2017, 2017, 9302761, 10.1155/2017/9302761.

- Birnbaum, J.H.; Wanner, D.; Gietl, A.F.; Saake, A.; Kundig, T.M.; Hock, C.; Nitsch, R.M.; Tackenberg, C.; Oxidative stress and altered mitochondrial protein expression in the absence of amyloid-beta and tau pathology in iPSC-derived neurons from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Stem cell research 2018, 27, 121–130, 10.1016/j.scr.2018.01.019.

- Martin-Maestro, P.; Gargini, R.; A., A.S.; Garcia, E.; Anton, L.C.; Noggle, S.; Arancio, O.; Avila, J.; Garcia-Escudero, V.; Mitophagy Failure in Fibroblasts and iPSC-Derived Neurons of Alzheimer’s Disease-Associated Presenilin 1 Mutation. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2017, 10, 291, 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00291.

- Li, L.; Roh, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Park, H.J.; Kim, M.; Koh, W.; Heo, H.; Chang, J.W.; Nakanishi, M.; Yoon, T.; et al.et al. The First Generation of iPSC Line from a Korean Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Carrying APP-V715M Mutation Exhibits a Distinct Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Experimental neurobiology 2019, 28, 329–336, 10.5607/en.2019.28.3.329.

- Repetto, M.G.; Reides, C.G.; Evelson, P.; Kohan, S.; de Lustig, E.S.; Llesuy, S.F.; Peripheral markers of oxidative stress in probable Alzheimer patients. European journal of clinical investigation 1999, 29, 643–649, 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00506.x.

- Kawamoto, E.M.; Munhoz, C.D.; Glezer, I.; Bahia, V.S.; Caramelli, P.; Nitrini, R.; Gorjao, R.; Curi, R.; Scavone, C.; Marcourakis, T.; et al. Oxidative state in platelets and erythrocytes in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 2005, 26, 857–864, 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.08.011.

- Ihara, Y.; Hayabara, T.; Sasaki, K.; Kawada, R.; Nakashima, Y.; Kuroda, S.; Relationship between oxidative stress and apoE phenotype in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neurologica Scandinavica 2000, 102, 346–349, 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.102006346.x.

- Ascolani, A.; Balestrieri, E.; Minutolo, A.; Mosti, S.; Spalletta, G.; Bramanti, P.; Mastino, A.; Caltagirone, C.; Macchi, B.; Dysregulated NF-kappaB pathway in peripheral mononuclear cells of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Current Alzheimer research 2012, 9, 128–137, 10.2174/156720512799015091.

- Behrens, M.I.; Silva, M.; Salech, F.; Ponce, D.P.; Merino, D.; Sinning, M.; Xiong, C.; Roe, C.M.; Quest, A.F.; Inverse susceptibility to oxidative death of lymphocytes obtained from Alzheimer’s patients and skin cancer survivors: Increased apoptosis in Alzheimer’s and reduced necrosis in cancer. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2012, 67, 1036–1040, 10.1093/gerona/glr258.

- Cecchi, C.; Fiorillo, C.; Sorbi, S.; Latorraca, S.; Nacmias, B.; Bagnoli, S.; Nassi, P.; Liguri, G.; Oxidative stress and reduced antioxidant defenses in peripheral cells from familial Alzheimer’s patients. Free radical biology & medicine 2002, 33, 1372–1379, 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01049-3.

- Cecchi, C.; Fiorillo, C.; Baglioni, S.; Pensalfini, A.; Bagnoli, S.; Nacmias, B.; Sorbi, S.; Nosi, D.; Relini, A.; Liguri, G.; et al. Increased susceptibility to amyloid toxicity in familial Alzheimer’s fibroblasts. Neurobiology of aging 2007, 28, 863–876, 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.014.

- Choi, J.; Malakowsky, C.A.; Talent, J.M.; Conrad, C.C.; Carroll, C.A.; Weintraub, S.T.; Gracy, R.W.; Anti-apoptotic proteins are oxidized by Abeta25-35 in Alzheimer’s fibroblasts. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2003, 1637, 135–141, 10.1016/s0925-4439(02)00227-2.

- Mota, S.I.; Costa, R.O.; Ferreira, I.L.; Santana, I.; Caldeira, G.L.; Padovano, C.; Fonseca, A.C.; Baldeiras, I.; Cunha, C.; Letra, L.; et al.et al. Oxidative stress involving changes in Nrf2 and ER stress in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2015, 1852, 1428–1441, 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.03.015.

- Piccini, A.; Fassio, A.; Pasqualetto, E.; Vitali, A.; Borghi, R.; Palmieri, D.; Nacmias, B.; Sorbi, S.; Sitia, R.; Tabaton, M.; et al. Fibroblasts from FAD-linked presenilin 1 mutations display a normal unfolded protein response but overproduce Abeta42 in response to tunicamycin. Neurobiology of disease 2004, 15, 380–386, 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.11.013.

- Martins, S.; Muller-Schiffmann, A.; Erichsen, L.; Bohndorf, M.; Wruck, W.; Sleegers, K.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; Korth, C.; Adjaye, J.; IPSC-Derived Neuronal Cultures Carrying the Alzheimer’s Disease Associated TREM2 R47H Variant Enables the Construction of an Abeta-Induced Gene Regulatory Network. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 4516, 10.3390/ijms21124516.

- Kondo, T.; Asai, M.; Tsukita, K.; Kutoku, Y.; Ohsawa, Y.; Sunada, Y.; Imamura, K.; Egawa, N.; Yahata, N.; Okita, K.; et al. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease with iPSCs reveals stress phenotypes associated with intracellular Abeta and differential drug responsiveness. Cell stem cell 2013, 12, 487–496, 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.009.