| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lida Fuentes-Viveros | + 2117 word(s) | 2117 | 2021-06-24 08:45:28 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2117 | 2021-07-01 04:59:43 | | |

Video Upload Options

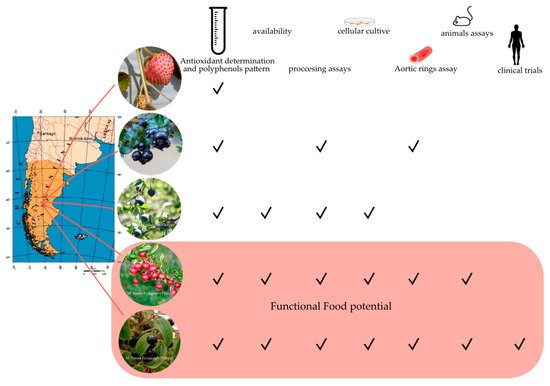

In this review, we focus on five fruit species growing in Patagonia with high potential as a functional food (i.e., maqui, murta, calafate, arrayán, and Chilean strawberry); giving a little background on the fruit quality; and discussing the recent research data available—regarding the particular compound profile, their processing, and clinical assays— of these Patagonian berries.

1. Introduction

|

Species |

Common Name |

Family |

Traditional Products and Uses |

Functional Products |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aristotelia chilensis (Mol.) Stuntz. |

Maqui |

Elaeocarpaceae |

Chile: from the Coquimbo to Aysén regions, including Juan Fernández Island (Latitude 31°–40°). Argentina: from Jujuy to Chubut provinces. |

Fresh and dried fruit, use to make textile pigment, cake, jam, juice, alcoholic beverages [25][26] |

Freeze-dried maqui (powder and capsules), honey mix, functional drinks, drugs [27][28][29][30][31][32][33] |

|

Ugni molinae Turcz. |

Murta |

Myrtaceae |

Chile: From the O’Higgins to Aysén regions, including Juan Fernández Island (Lat. 34°–40°). Argentina: Neuquén, Rio Negro, and Chubut provinces. |

Fresh and dried fruit, textile pigment, bakery, jam, alcoholic beverages [26] |

Freeze-dried murta (powder and capsules), honey mix [33][34] |

|

Berberis microphylla G. Forst. |

Calafate |

Berberidaceae |

Chile: From the Metropolitan to Magallanes regions (Lat. 33°–55°). Argentina: From Neuquén to Tierra del Fuego provinces. |

Natural colorants [26] |

|

|

Luma apiculata (DC.) Burret. |

Arrayán |

Myrtaceae |

Chile: From the Coquimbo to Aysén regions (Lat. 31°–40°). Argentina: From Neuquén to Chubut provinces. |

Fresh fruit, textile pigment, bakery, jam, aromatic wine [22][23] |

N.D. |

|

Fragaria chiloensis (L.) Mill. |

Chilean strawberry |

Rosaceae |

Chile: From the O’Higgins to Magallanes regions (Lat. 34°–55°). Argentina: Neuquén and Rio Negro provinces. |

Fresh fruit, used to make alcoholic beverages, cake [25][35] |

N.D. |

2. Quality Aspects and Bioactive Compounds of Patagonian Berries

2.1. Fruit Quality

2.2. Antioxidant Capacity

|

Species Name |

Average Antioxidant Capacity Determined by ORAC (µmol·100 g DW−1) a |

Average Range of Total Polyphenols Compounds Content (mg GAE g−1 DW−1) a |

Number of Non-Anthocyanin Polyphenol Compounds Reported |

Principal Non-Anthocyanin Polyphenol Compounds |

Number of Anthocyanin Compound Reported |

Principal Anthocyanin Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Maqui. |

49.7 [50] |

13 [15] |

Quercetin, dimethoxy-quercetin, quercetin-3-rutinoside, quercetin-3-galactoside, myricetin and its derivatives (dimethoxy-quercetin) and ellagic acid [50] |

8 [15] |

3-glucosides, 3,5-diglucosides, 3-sambubiosides and 3-sambubioside-5-glucosides of cyanidin and delphinidin (delphinidin 3-sambubioside-5-glucoside) [20][51] |

|

|

Murta |

16 [15] |

caffeic acid-3-glucoside, quercetin-3-glucoside, quercetin, gallic acid, quercetin-3-rutinoside, quercitrin, luteolin, luteolin-3-glucoside, kaempferol, kaempferol-3-glucoside, myricetin and p-coumaric acid [52] |

11 [15] |

delphinidin-3-, malvidin-3- and peonidin-3-arabinoside; peonidin-3- and malvidin-3-glucoside [20][52] |

||

|

Calafate |

36 [15] |

quercetin-3-rutinoside, gallic- and chlorogenic acid, caffeic and the presence of coumaric- and ferulic acid, quercetin, myricetin, and kaempferol [19] |

30 [15] |

delphinidin-3-glucoside, delphinidin-3-rutinoside, delphinidin-3,5-dihexoside, cyanidin-3-glucoside, petunidin-3-glucoside, petunidin-3-rutinoside, petunidin-3,5-dihexoside, malvidin-3-glucoside and malvidin-3-rutinoside [19][20] |

||

|

Arrayán |

62,500 [21] |

27.6 [19] |

13 [15] |

quercetin 3-rutinoside and their derivatives, tannins and their monomers [18][21] |

8 [15] |

peonidin-3-galactoside, petunidin-3-arabinoside, malvidin-3-arabinoside, peonidin-3-arabinoside delphinidin-3-arabinoside, cyanidin-3-glucoside, peonidin-3-glucoside and malvidin-3-glucoside [18][19][21] |

|

Chilean strawberry |

N.R. |

N.R |

16*20** [17] |

ellagic acid and their pentoside- and rhamnoside derivatives. quercetin glucuronide, ellagitannin, quercetin pentoside, kaempferol glucuronide. Catechin *, quercetin pentosid *, and quercetin hexoside * procyanidin tetramers ** and ellagitannin ** [17] |

4 [17] |

cyanidin 3-O-glucoside, pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside, cyanidin-malonyl-glucoside and pelargonidin-malonyl- glucoside [17] |

3. Effects of Processing on Bioactive Compounds

4. Healthy Potential of Patagonian berries

References

- Coronato, A.; Coronato, F.; Mazzoni, E.; Vázquez, M. The physical geography of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. The Late Cenozoic of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego; Rabassa, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 13–56.

- Hoffmann, A.; Farga, C.; Lastra, J.; Veghazi, E. Plantas Medicinales de Uso Comun en Chile; Fundación Claudio Gay: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 1992; 257p.

- Mösbach, E.W. Botánica Indígena de Chile; Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino; Editorial Andrés Bello; Fundación Andes: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 1992; 140p.

- Ladio, A.H.; Lozada, M. Patterns of use and knowledge of wild edible plants in distinct ecological environments: A case study of a Mapuche community from Nothwestern Patagonia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 1153–1173.

- Estomba, D.; Ladio, A.; Lozada, M. Medicinal wild plant knowledge and gathering patterns in a Mapuche community from North-western Patagonia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 103, 109–119.

- Díaz-Forestier, J.; León-Lobos, L.; Marticorena, A.; Celis-Diez, J.L.; Giovannini, P. Native Useful Plants of Chile: A Review and Use Patterns. Econ. Bot. 2019, 73, 112–126.

- Barreau, A.; Ibarra, J.T.; Wyndham, F.S.; Rojas, A.; Kozak, R.A. How can we teach our children if we cannot access the forest? Generational change in mapuche knowledge of wild edible plants in Andean temperature ecosystems of Chile. J. Ethnobiol. 2016, 36, 412–432.

- Rivera, D.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J.; Inocencio, C.; Obon, C.; Heinrich, M. Guia Etnobotanica de los Alimentos Locales Recolectados en la Provincia de Albacete; Instituto de Estudios Albacetenses; Diputación de Albacete: Albacete, Spain, 2006.

- Egea, I.; Sánchez-Bel, P.; Romojaro, F.; Pretel, M.T. Six edible wild fruits as potential antioxidant additives or nutritional supplements. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2010, 65, 121–129.

- Pereira, M.C.; Steffens, R.S.; Jablonski, A.; Hertz, P.F.; Rios Ade, O.; Vizzotto, M.; Flôres, S.H. Characterization and antioxidant potential of Brazilian fruits from the Myrtaceae family. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3061–3067.

- Speisky, H.; López Alarcón, C.; Gómez, M.; Fuentes, J.; Sandoval Acuña, C. First web-based database on total phenolics and oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) of fruits produced and consumed within the South Andes Region of South America. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8851–8859.

- Ramos, A.S.; Souza, R.O.S.; Boleti, A.P.A.; Bruginski, E.R.D.; Lima, E.S.; Campos, F.R.; Machado, M.B. Chemical characterization and antioxidant capacity of the araçá-pera (Psidium acutangulum): An exotic Amazon fruit. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 315–327.

- Kongkachuichai, R.; Charoensiri, R.; Yakoh, K.; Kringkasemsee, A.; Insung, P. Nutrients value and antioxidant content of indigenous vegetables from Southern Thailand. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 838–846.

- Barros, R.G.C.; Andrade, J.K.S.; Denadai, M.; Nunes, M.L.; Narain, N. Evaluation of bioactive compounds potential and antioxidant activity in some Brazilian exotic fruit residues. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 84–92.

- Ulloa-Inostroza, E.M.; Ulloa-Inostroza, E.G.; Alberdi, M.; Peña-Sanhueza, D.; González-Villagra, J.; Jaakola, L.; Reyes-Díaz, M. Native Chilean Fruits and the Effects of their Functional Compounds on Human Health, Superfood and Functional Food Viduranga Waisundara. Available online: (accessed on 29 June 2019).

- Schmeda-Hirschmann, G.; Jiménez-Aspee, F.; Theoduloz, C.; Ladio, A. Patagonian berries as native food and medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 241, 111979.

- Simirgiotis, M.J.; Theoduloz, C.; Caligari, P.D.S.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G. Comparison of phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of two native Chilean and one domestic strawberry genotypes. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 377–385.

- Simirgiotis, M.J.; Bórquez, J.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G. Antioxidant capacity, polyphenol content and tandem HPLCDAD- ESI/MS profiling of phenolic compounds from the South American berries Luma apiculata and L. chequen. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 289–299.

- Brito, A.; Areche, C.; Sepúlveda, B.; Kennelly, E.; Simirgiotis, M. Anthocyanin characterization, total phenolic quantification and antioxidant features of some Chilean edible berry extracts. Molecules 2014, 19, 10936–10955.

- Ruiz, A.; Hermosín, I.; Mardones, C.; Vergara, C.; Herlitz, C.; Vega, M.; Dorau, C.; Winterhalter, P.; Von Baer, D. Polyphenols and antioxidant activity of calafate (Berberis microphylla) fruits and other native berries from southern Chile. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6081–6089.

- Fuentes, L.; Valdenegro, M.; Gómez, M.G.; Ayala-Raso, A.; Quiroga, E.; Martínez, J.P.; Vinet, R.; Caballero, E.; Figueroa, C.R. Characterization of fruit development and potential health benefits of arrayan (Luma apiculata), a native berry of South America. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 1239–1247.

- Rozzi, R.; Massardo, F. Las Plantas Medicinales Chilenas II y III. Informe Nueva Medicina 1994, 1, 16–17.

- Massardo, F.; Rozzi, R. Usos medicinales de la flora nativa chilena. Ambiente y Desarrollo 1996, 12, 76–81.

- Rodriguez, R.; Marticorena, C.; Alarcón, D.; Baeza, C.; Cavieres, L.; Finot, V.L.; Fuentes, N.; Kiessling, A.; Mihoc, M.; Pauchard, A.; et al. Catálogo de las plantas vasculares de Chile. Gayana Botánica 2018, 75, 1–430.

- Gomes, F.C.; Lacerda, I.C.; Libkind, D.; Lopes, C.; Carvajal, E.J.; Rosa, C.A. Traditional foods and beverages from South America: Microbial communities and production strategies. Ind. Ferment. Food Process. Nutr. Sour. Prod. Strateg. 2009, 3, 79–114.

- Hoffmann, A.E. Flora Silvestre de Chile, 5th ed.; Zona Araucana Edicione; Fundación Claudio Gay: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2005; 257p.

- Alvarado, J.; Schoenlau, F.; Leschot, A.; Salgad, A.M.; Vigil Portales, P. Delphinol® standardized maqui berry extract significantly lowers blood glucose and improves blood lipid profile in prediabetic individuals in three-month clinical trial. Panminerva Med. 2016, 58 (Suppl. 1), 1–6.

- Alvarado, J.; Leschot, A.; Olivera Nappa, Á.; Salgado, A.; Rioseco, H.; Lyon, C.; Vigil, P. Delphinidin-Rich Maqui Berry Extract (Delphinol (R)) Lowers Fasting and Postprandial Glycemia and Insulinemia in Prediabetic Individuals during Oral Glucose Tolerance Tests. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016b, 9070537.

- Watson, R.R.; Schönlau, F. Nutraceutical and antioxidant effects of a delphinidin-rich maqui berry extract Delphinol®: A review. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2015, 63 (Suppl. 1), 1–12.

- Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Aranda, M. Evaluation of phenolic profiles and antioxidant capacity of maqui (Aristotelia chilensis) berries and their relationships to drying methods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 4168–4176.

- Rodríguez, K.; Ah-Hen, K.S.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Vásquez, V.; Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Rojas, P.; Lemus-Mondaca, R. Changes in bioactive components and antioxidant capacity of maqui, Aristotelia chilensis [Mol] Stuntz, berries during drying. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 537–542.

- Romo, R.; Bastías, J.M. Estudio de Mercado del Maqui. PYT-0215-0219. Perspectiva del Mercado Internacional para el Desarrollo de la Industria del Maqui: Un Análisis de las Empresas en Chile. Available online: (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Estudio Preparación de Expedientes Técnicos para la Presentación y Solicitud de Autorización de Alimentos Nuevos o Tradicionales de Terceros Países para Exportar a la Unión Europea. Available online: (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Puente-Díaz, L.K.; Ah-Hen, A.; Vega-Gálvez, R.; Lemus-Mondaca; Di Scala, K. Combined infrared-convective drying of murta (Ugni molinae Turcz.) berries: Kinetic modeling and quality assessment. Dry Technol. 2013, 31, 329–338.

- Figueroa, C.R.; Concha, C.M.; Figueroa, N.E.; Tapia, G. Frutilla Chilena Nativa Fragaria chiloensis. Available online: (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Reyes-Farias, M.; Vasquez, K.; Ovalle-Marin, A.; Fuentes, F.; Parra, C.; Quitral, V.; Jimenez, P.; Garcia-Diaz, D.F. Chilean native fruit extracts inhibit inflammation linked to the pathogenic interaction between adipocytes and macrophages. J. Med. Food 2015, 18, 601–608.

- Barrett, D.M.; Beaulieu, J.C.; Shewfelt, R. Color, flavor, texture, and nutritional quality of fresh-cut fruits and vegetables: Desirable levels, instrumental and sensory measurement, and the effects of processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 369–389.

- Kramer, A. Evaluation of quality of fruits and vegetables. In Food Quality; Irving, G.W., Jr., Hoover, S.R., Eds.; American Association for the Advancement of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 1965; pp. 9–18.

- Fuentes, L.; Figueroa, C.R.; Valdenegro, M. Recent Advances in Hormonal Regulation and Cross-Talk during Non-Climacteric Fruit Development and Ripening. Horticulturae 2019, 5, 45.

- Dixon, R.A.; Paiva, N.L. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1085.

- Landrum, L.; Donoso, C. Ugni molinae (Myrtaceae), a potential fruit crop for regions of Mediterranean, maritime and subtropical climates. Econ. Bot. 1990, 44, 536–539.

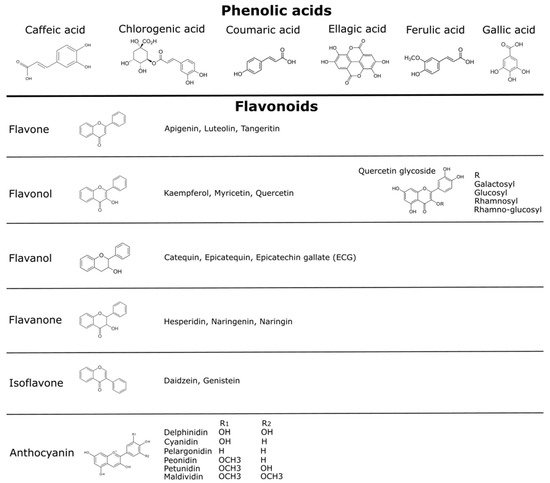

- Rice-Evans, C.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 933–956.

- Rice-Evans, C.; Miller, N.; Paganga, G. Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 152–159.

- Soto-Vaca, A.; Gutierrez, A.; Losso, J.N.; Xu, Z.; Finley, J.W. Evolution of phenolic compounds from color and flavor problems to health benefits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6658–6677.

- Scalbert, A.; Manach, C.; Morand, C.; Remesy, C. Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 45, 287–306.

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352.

- Russo, B.; Picconi, F.; Malandrucco, I.; Frontoni, S. Flavonoids and Insulin-Resistance: From Molecular Evidences to Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2061.

- Wikimedia Commons. Available online: (accessed on 26 May 2019).

- Portal Antioxidantes. Available online: (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Genskowsky, E.; Puente, L.A.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J.; Muñoz, L.A.; Viuda-Martos, M. Determination of polyphenolic profile, antioxidant activity and antibacterial properties of maqui [Aristotelia chilensis (Molina) Stuntz] a Chilean blackberry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4235–4242.

- Escribano-Bailón, M.; Alcalde-Eon, C.; Muñoz, O.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.; Santos-Buelga, C. Anthocyanins in berries of maqui (Aristotelia chilensis (Mol.) Stuntz). Phytochem. Anal. 2006, 17, 8–14.

- Junqueira-Gonçalves, M.P.; Yáñez, L.; Morales, C.; Navarro, M.; AContreras, R.; Zúñiga, G.E. Isolation and characterization of phenolic compounds and anthocyanins from Murta (Ugni molinae Turcz.) fruits. Assessment of antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Molecules 2015, 20, 5698–5713.

- Dávalos, A.; Gómez-Cordovés, C.; Bartolomé, B. Extending applicability of the oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC—fluorescein) assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 48–54.

- Fredes, C.; Montenegro, G.; Zoffoli, J.P.; Santander, F.; Robert, P. Comparison of the total phenolic content, total anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity of polyphenol-rich fruits grown in Chile. Cienc. Investig. Agrar. 2014, 41, 49–60.

- Céspedes, C.; El-Hafidi, M.; Pavon, N.; Alarcon, J. Antioxidant and cardioprotective activities of phenolic extracts from fruits of Chilean blackberry Aristotelia chilenesis (Elaeocarpaceae), Maqui. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 820–829.

- Mahdavi, S.A.; Jafari, S.M.; Ghorbani, M.; Assadpoor, E. Spray-drying microencapsulation of anthocyanins by natural biopolymers: A review. Drying Technol. 2014, 32, 509–518.

- Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Ihl, M.; Bifani, V.; Silva, A.; Montero, P. Edible films made from tuna-fish gelatin with antioxidant extracts of two different murta ecotypes leaves (Ugni molinae Turcz.). Food Hydrocoll. 2007, 21, 1133–1143.

- Stevenson, D.E.; Hurst, R.D. Polyphenolic phytochemicals—Just antioxidants or much more? Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 2900–2916.

- Amiot, M.J.; Riva, C.A.V. Effects of dietary polyphenols on metabolic syndrome features in humans: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 573–586.

- Hussain, T.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F.; Tossou, M.C.; Rahu, N. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: What Polyphenols Can Do for Us? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016.

- D’Archivio, M.; Filesi, C.; Varì, R.; Scazzocchio, B.; Masella, R. Bioavailability of the polyphenols: Status and controversies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1321–1342.

- Rubió, L.; Macià, A.; Motilva, M.J. Impact of various factors on pharmacokinetics of bioactive polyphenols: An overview. Curr. Drug Metab. 2014, 15, 62–76.

- Zhang, H.; Yu, D.; Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Jiang, L.; Guo, H.; Ren, F. Interaction of plant phenols with food macronutrients: Characterisation and nutritional-physiological consequences. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2014, 27, 1–15.

- Manach, C.; Williamson, G.; Morand, C.; Scalbert, A.; Rémésy, C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81 (Suppl. 1), 230S–242S.