Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elena Antontseva | + 1154 word(s) | 1154 | 2021-06-21 11:05:28 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 1154 | 2021-06-29 10:01:44 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Antontseva, E. Regulatory SNPs. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11441 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Antontseva E. Regulatory SNPs. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11441. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Antontseva, Elena. "Regulatory SNPs" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11441 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Antontseva, E. (2021, June 29). Regulatory SNPs. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11441

Antontseva, Elena. "Regulatory SNPs." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 June, 2021.

Copy Citation

Regulatory SNPs are genetic variants that associated with various human traits and diseases map to a noncoding part of the genome and are enriched in its regulatory compartment, suggesting that many causal variants may affect gene expression. The leading mechanism of action of these SNPs consists in the alterations in the transcription factor binding via creation or disruption of transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) or some change in the affinity of these regulatory proteins to their cognate sites.

regulatory SNPs

transcription factor binding sites

gene expression

gene by gene studies

genome wide approaches

1. Introduction

A central goal of human genetics is to understand how genetic variation leads to phenotypic differences and complex diseases. Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have detected over 70 thousand variants (mainly, single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) associated with various human traits and diseases [1][2]. The vast majority of the genetic variants identified from GWAS map to the noncoding part of the genome and are enriched in regulatory regions (promoters, enhancers, etc.), suggesting that many causal variants may affect gene expression [3][4][5][6].

As is known, the regulatory regions of the genome represent clusters of the binding sites for sequence-specific transcription factors (TFs). There, the interplay between these TFs and their binding sites (cis-regulatory elements) as well as the interaction of TFs with one another and the coactivator and chromatin remodeling complexes orchestrate the dynamic and diverse genetic programs, thereby determining the tissue-specific gene expression, spatiotemporal specificity of gene activities during development, and the ability of genes to respond to different external signals [7][8][9][10][11][12]. Thus, thanks to the binding to their specific sites on DNA (transcription factor binding sites, TFBSs), TFs directly interpret the regulatory part of the genome, performing the first step in deciphering the DNA sequence [13][14][15]. Consequently, regulatory SNPs (rSNPs), that is, genetic variation within TFBSs that alters expression, play a central role in the phenotypic variation in complex traits, including the risk of developing a disease.

Starting from the 1990s, numerous studies have been performed focusing on the noncoding SNPs that perturb the TF binding and are associated with various pathologies. As has been shown, risk alleles can (i) destroy a binding site for a TF [16][17][18][19]; (ii) create a binding site for a TF [20][21][22]; or alter the binding affinities towards an increase [23][24][25] or a decrease [25][26][27][28]. In addition, several cases have been observed when a damage/destruction of a binding site for a TF leads to a concurrent formation of another/other TFBS(s) [19][29][30].

The advent of the NGS technologies gave a strong impetus to the development of functional genomics and application of its methods to the genome-wide search for rSNPs. Currently, various methods of functional genomics are used for both mass interpretation of GWAS data and independent genome-wide identification of regulatory variants. So far, expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) mapping and identification of allele-specific expression (ASE) events utilizing analysis of RNA-seq data (actually, the largest available genome-wide dataset) are the major relevant methods. The search for allele-specific binding (ASB) events in the data of DNase-seq, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing), and so on becomes ever more important. In addition, the approaches not directly associated with obtaining genome-wide data are actively used, including massively parallel reporter assay (MPRA), SNPs-seq, and SNPs-SELEX.

2. rSNPs on a Genome-Wide Scale

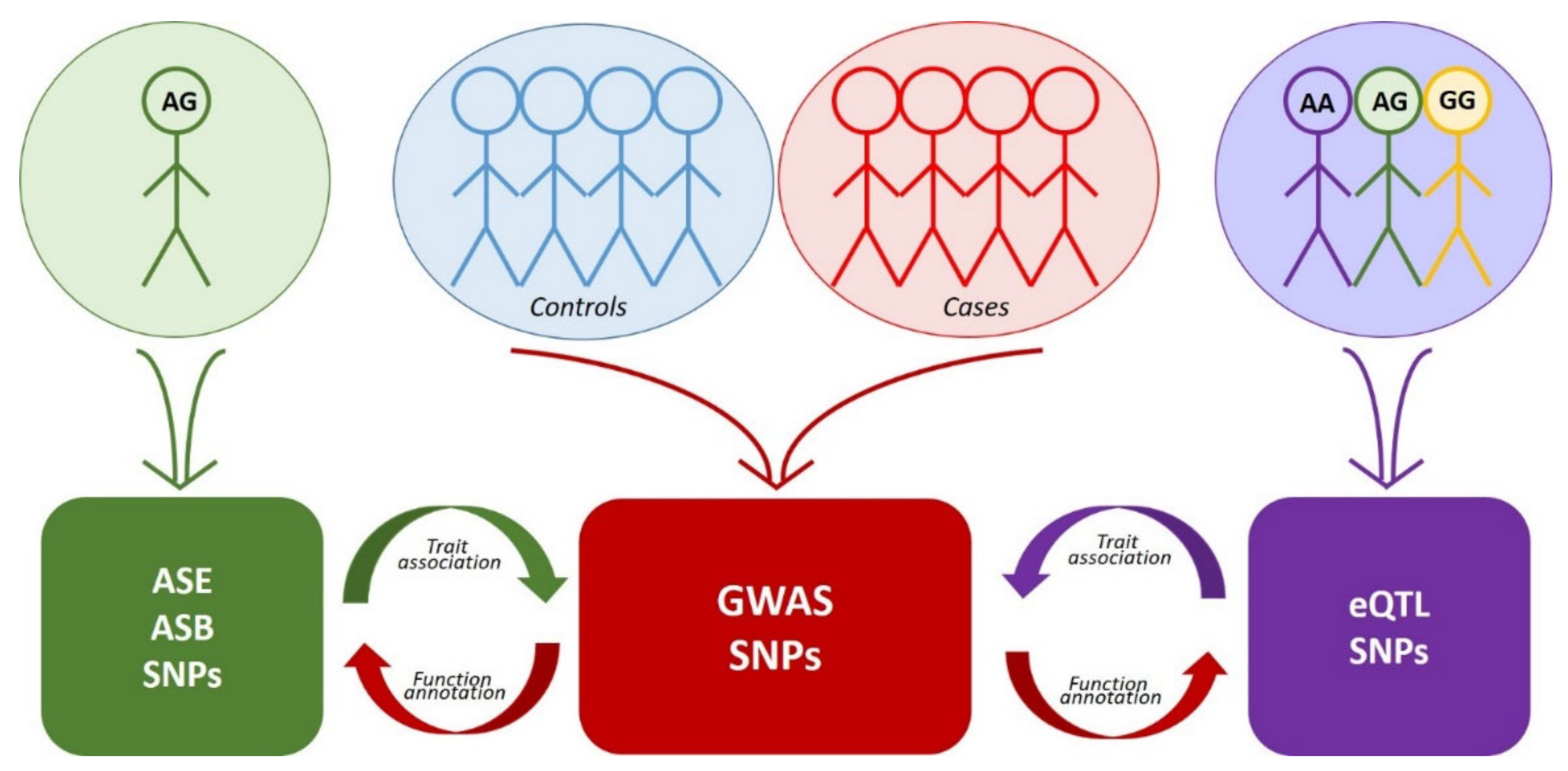

Genome-wide approaches to the search for rSNPs fall into two large groups. The first group comprises GWAS mass data analysis utilizing manifold methods of functional genomics, while the second group uses the same methods but independently without any prior knowledge about trait associations (Figure 1, Table 1). The latter group includes eQTL analysis, identification of allele-specific events, and some other genome-wide approaches. As for the rSNPs discovered by the approaches of the second group, it is necessary to additionally determine their association with a certain trait (most frequently, via comparison with GWAS data or by analysis of rSNPs as an eQTL in transcriptome data and reconstruction of the gene networks and molecular pathways).

Figure 1. Interplay between the approaches to the search for functional SNPs. Colored blocks denote arrays of corresponding data. Red arrows indicate functional annotation of GWAS data using eQTL, ASE or ASB analysis. Purple arrow indicates the search for association of eQTL SNPs with traits via comparison with GWAS data. Green arrow—the same for SNPs detected by ASE or ASB analysis.

Figure 1. Interplay between the approaches to the search for functional SNPs. Colored blocks denote arrays of corresponding data. Red arrows indicate functional annotation of GWAS data using eQTL, ASE or ASB analysis. Purple arrow indicates the search for association of eQTL SNPs with traits via comparison with GWAS data. Green arrow—the same for SNPs detected by ASE or ASB analysis.Table 1. Main features of the most widespread approaches to the search for functional SNPs.

| Approach | GWAS | eQTL Analysis | ASE | ASB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial association with trait |

+ | − | − | − |

| 2 | Initial association with function |

− | + | + | + |

| 3 | Causal or in LD | Both | + | ++ | +++ |

| 4 | Number of participants | Tens and hundreds of thousands (large cohorts) |

Hundreds (modestly sized cohorts) |

Few | Few |

In row 3, +/++/+++ shows an increase in the bias towards causal.

3. Conclusions

Gene expression programs underlying development, differentiation, and environmental responses are guided by the regulatory DNA portion of the metazoan genomes. The corresponding information encoded in regulatory DNA is actuated via the combinatorial binding of sequence-specific TFs to regulatory regions (cis-regulatory modules, CRMs). CRMs switch on promoters and enhancers and are actually the assemblies of TFBSs arranged to provide particular functions [10][11][14][31][32][33].

The SNPs located in transcriptional regulatory regions can alter gene expression, which may be either adaptive or lead to a disease. The main mechanism underlying the action of these SNPs consists in changes of TF binding, which comprises creation or disruption of TFBSs (cis-regulatory elements) or alteration of the affinity of TFs for their cognate sites [34][35][36][37]. Although many SNPs with such properties have been so far discovered, their mass search in genomes remains challenging. This is mainly associated with the tissue, developmental, and environmental specificities in the effects of rSNPs, which is a direct consequence of the corresponding specificities of the harboring cis-regulatory elements [34][38][39]. Thus, myriads of omics experiments are necessary for this purpose; however, this is still too expensive and time-consuming. The computer methods for recognition of TFBSs in DNA sequences are free of this disadvantage but yet ineffective in detection of both TFBSs and the SNPs changing these sites without the cooperation with omics experiments. The objective reasons here are a high degeneracy of the regulatory DNA code [15][40][41][42]; high importance of low-affinity sites in gene regulation [43]; the presence of structural variants of the binding sites for the same TF [44][45][46][47]; and even nonconsensus TFBSs [48][49]. All these facts considerably decrease the efficacy of the available methods for TFBS recognition, most of which are based on the PWM model, which oversimplifies the mechanisms underlying TF–DNA interaction [50][51][52][53]. Development of new generation bioinformatics approaches relying on machine learning and neural networks raises the hope for more efficient and accurate recognition of both the TFBSs and rSNPs in the genomes [54][55][56][57][58][59].

Thus, despite the achieved progress, we are still at the beginning of the way to comprehensive annotation of the genome regulatory portion, full cataloging of rSNPs, and clarification of their association with molecular phenotypes and, eventually, with various complex traits, including diseases. The further advance requires improving the efficiency of the existing experimental and bioinformatics methods of systems biology and advent of the new relevant approaches.

References

- Buniello, A.; MacArthur, J.A.L.; Cerezo, M.; Harris, L.W.; Hayhurst, J.; Malangone, C.; McMahon, A.; Morales, J.; Mountjoy, E.; Sollis, E.; et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1005–D1012.

- Claussnitzer, M.; Cho, J.H.; Collins, R.; Cox, N.J.; Dermitzakis, E.T.; Hurles, M.E.; Kathiresan, S.; Kenny, E.E.; Lindgren, C.M.; MacArthur, D.G.; et al. A brief history of human disease genetics. Nature 2020, 577, 179–189.

- Bryzgalov, L.O.; Antontseva, E.V.; Matveeva, M.Y.; Shilov, A.G.; Kashina, E.V.; Mordvinov, V.A.; Merkulova, T.I. Detection of Regulatory SNPs in Human Genome Using ChIP-seq ENCODE Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78833.

- Farh, K.K.-H.; Marson, A.; Zhu, J.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Housley, W.J.; Beik, S.; Shoresh, N.; Whitton, H.; Ryan, R.J.H.; Shishkin, A.A.; et al. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature 2015, 518, 337–343.

- Maurano, M.T.; Humbert, R.; Rynes, E.; Thurman, R.E.; Haugen, E.; Wang, H.; Reynolds, A.P.; Sandstrom, R.; Qu, H.; Brody, J.; et al. Systematic Localization of Common Disease-Associated Variation in Regulatory DNA. Science 2012, 337, 1190–1195.

- GTEx Consortium. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature 2017, 550, 204–213.

- Levo, M.; Segal, E. In pursuit of design principles of regulatory sequences. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 453–468.

- Andersson, R. Promoter or enhancer, what’s the difference? Deconstruction of established distinctions and presentation of a unifying model. BioEssays 2015, 37, 314–323.

- Erokhin, M.; Vassetzky, Y.; Georgiev, P.; Chetverina, D. Eukaryotic enhancers: Common features, regulation, and participation in diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 2361–2375.

- Chen, H.; Pugh, B.F. What Do Transcription Factors Interact with? J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 166883.

- Tobias, I.C.; Abatti, L.E.; Moorthy, S.D.; Mullany, S.; Taylor, T.; Khader, N.; Filice, M.A.; Mitchell, J.A. Transcriptional enhancers: From prediction to functional assessment on a genome-wide scale. Genome 2021, 64, 426–448.

- Singh, G.; Mullany, S.; Moorthy, S.D.; Zhang, R.; Mehdi, T.; Tian, R.; Duncan, A.G.; Moses, A.M.; Mitchell, J.A. A flexible repertoire of transcription factor binding sites and a diversity threshold determines enhancer activity in embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 564–575.

- Lambert, S.A.; Jolma, A.; Campitelli, L.F.; Das, P.K.; Yin, Y.; Albu, M.; Chen, X.; Taipale, J.; Hughes, T.R.; Weirauch, M.T. The Human Transcription Factors. Cell 2018, 175, 598–599.

- Lelli, K.M.; Slattery, M.; Mann, R.S. Disentangling the Many Layers of Eukaryotic Transcriptional Regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012, 46, 43–68.

- Merkulova, T.I.; Ananko, E.A.; Ignat’eva, E.V.; Kolchanov, N.A. Regulatory transcription codes in eukaryotic genomes. Genetika 2013, 49, 37–54.

- Wang, Y.; Ma, R.; Liu, B.; Kong, J.; Lin, H.; Yu, X.; Wang, R.; Li, L.; Gao, M.; Zhou, B.; et al. SNP rs17079281 decreases lung cancer risk through creating an YY1-binding site to suppress DCBLD1 expression. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4092–4102.

- Padhy, B.; Hayat, B.; Nanda, G.G.; Mohanty, P.P.; Alone, D.P. Pseudoexfoliation and Alzheimer’s associated CLU risk variant, rs2279590, lies within an enhancer element and regulates CLU, EPHX2 and PTK2B gene expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 4519–4529.

- Krause, M.D.; Huang, R.-T.; Wu, D.; Shentu, T.-P.; Harrison, D.L.; Whalen, M.B.; Stolze, L.K.; Di Rienzo, A.; Moskowitz, I.P.; Civelek, M.; et al. Genetic variant at coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke locus 1p32.2 regulates endothelial responses to hemodynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, e11349–e11358.

- Hazelett, D.J.; Rhie, S.K.; Gaddis, M.; Yan, C.; Lakeland, D.L.; Coetzee, S.G.; Henderson, B.E.; Noushmehr, H.; Cozen, W.; Kote-Jarai, Z.; et al. Comprehensive Functional Annotation of 77 Prostate Cancer Risk Loci. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004102.

- Gao, P.; Xia, J.-H.; Sipeky, C.; Dong, X.-M.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Cruz, S.P.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, J.; et al. Biology and Clinical Implications of the 19q13 Aggressive Prostate Cancer Susceptibility Locus. Cell 2018, 174, 576–589.e18.

- Afanasyeva, M.A.; Putlyaeva, L.V.; Demin, D.E.; Kulakovskiy, I.V.; Vorontsov, I.E.; Fridman, M.V.; Makeev, V.J.; Kuprash, D.V.; Schwartz, A.M. The single nucleotide variant rs12722489 determines differential estrogen receptor binding and enhancer properties of an IL2RA intronic region. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172681.

- Korneev, K.V.; Sviriaeva, E.N.; Mitkin, N.A.; Gorbacheva, A.M.; Uvarova, A.N.; Ustiugova, A.S.; Polanovsky, O.L.; Kulakovskiy, I.V.; Afanasyeva, M.A.; Schwartz, A.M.; et al. Minor C allele of the SNP rs7873784 associated with rheumatoid arthritis and type-2 diabetes mellitus binds PU.1 and enhances TLR4 expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165626.

- Fang, J.; Jia, J.; Makowski, M.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Hoskins, J.W.; Choi, J.; Han, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Functional characterization of a multi-cancer risk locus on chr5p15.33 reveals regulation of TERT by ZNF148. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15034.

- Choi, J.; Zhang, T.; Vu, A.; Ablain, J.; Makowski, M.M.; Colli, L.M.; Xu, M.; Hennessey, R.C.; Yin, J.; Rothschild, H.; et al. Massively parallel reporter assays of melanoma risk variants identify MX2 as a gene promoting melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2718.

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, D.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Wu, T.; Cui, J.; Qian, M.; Zhao, J.; Oesterreich, S.; Sun, W.; et al. A sequential methodology for the rapid identification and characterization of breast cancer-associated functional SNPs. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3340.

- Prestel, M.; Prell-Schicker, C.; Webb, T.; Malik, R.; Lindner, B.; Ziesch, N.; Rex-Haffner, M.; Röh, S.; Viturawong, T.; Lehm, M.; et al. The Atherosclerosis Risk Variant rs2107595 Mediates Allele-Specific Transcriptional Regulation of HDAC9 via E2F3 and Rb1. Stroke 2019, 50, 2651–2660.

- Thomas, R.; Trapani, D.; Goodyer-Sait, L.; Tomkova, M.; Fernandez-Rozadilla, C.; Sahnane, N.; Woolley, C.; Davis, H.; Chegwidden, L.; Kriaucionis, S.; et al. The polymorphic variant rs1800734 influences methylation acquisition and allele-specific TFAP4 binding in the MLH1 promoter leading to differential mRNA expression. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13463.

- Jiang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Han, C.; Lu, Y.; Mo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Cai, F.; et al. Characterization of a pathogenic variant in GBA for Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment patients. Mol. Brain 2020, 13, 102.

- Allen, E.K.; Randolph, A.G.; Bhangale, T.; Dogra, P.; Ohlson, M.; Oshansky, C.M.; Zamora, A.E.; Shannon, J.P.; Finkelstein, D.; Dressen, A.; et al. SNP-mediated disruption of CTCF binding at the IFITM3 promoter is associated with risk of severe influenza in humans. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 975–983.

- Vasiliev, G.V.; Merkulov, V.M.; Kobzev, V.F.; Merkulova, T.I.; Ponomarenko, M.P.; Kolchanov, N.A. Point mutations within 663–666 bp of intron 6 of the human TDO2 gene, associated with a number of psychiatric disorders, damage the YY-1 transcription factor binding site. FEBS Lett. 1999, 462, 85–88.

- Dubois-Chevalier, J.; Mazrooei, P.; Lupien, M.; Staels, B.; Lefebvre, P.; Eeckhoute, J. Organizing combinatorial transcription factor recruitment at cis -regulatory modules. Transcription 2018, 9, 233–239.

- Gerstein, M.B.; Kundaje, A.; Hariharan, M.; Landt, S.G.; Yan, K.-K.; Cheng, C.; Mu, X.J.; Khurana, E.; Rozowsky, J.; Alexander, R.; et al. Architecture of the human regulatory network derived from ENCODE data. Nature 2012, 489, 91–100.

- Lan, X.; Farnham, P.J.; Jin, V.X. Uncovering Transcription Factor Modules Using One- and Three-dimensional Analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 30914–30921.

- Deplancke, B.; Alpern, D.; Gardeux, V. The Genetics of Transcription Factor DNA Binding Variation. Cell 2016, 166, 538–554.

- Maurano, M.T.; Haugen, E.; Sandstrom, R.; Vierstra, J.; Shafer, A.; Kaul, R.; Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A. Large-scale identification of sequence variants influencing human transcription factor occupancy in vivo. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1393–1401.

- Gan, K.A.; Carrasco Pro, S.; Sewell, J.A.; Fuxman Bass, J.I. Identification of Single Nucleotide Non-coding Driver Mutations in Cancer. Front. Genet. 2018, 9.

- Carrasco Pro, S.; Bulekova, K.; Gregor, B.; Labadorf, A.; Fuxman Bass, J.I. Prediction of genome-wide effects of single nucleotide variants on transcription factor binding. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17632.

- Liu, B.; Montgomery, S.B. Identifying causal variants and genes using functional genomics in specialized cell types and contexts. Hum. Genet. 2020, 139, 95–102.

- GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 2020, 369, 1318–1330.

- Kolchanov, N.A.; Merkulova, T.I.; Ignatieva, E.V.; Ananko, E.A.; Oshchepkov, D.Y.; Levitsky, V.G.; Vasiliev, G.V.; Klimova, N.V.; Merkulov, V.M.; Charles Hodgman, T. Combined experimental and computational approaches to study the regulatory elements in eukaryotic genes. Brief. Bioinform. 2007, 8, 266–274.

- Badis, G.; Berger, M.F.; Philippakis, A.A.; Talukder, S.; Gehrke, A.R.; Jaeger, S.A.; Chan, E.T.; Metzler, G.; Vedenko, A.; Chen, X.; et al. Diversity and Complexity in DNA Recognition by Transcription Factors. Science 2009, 324, 1720–1723.

- Nagy, G.; Nagy, L. Motif grammar: The basis of the language of gene expression. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2026–2032.

- Crocker, J.; Preger-Ben Noon, E.; Stern, D.L. The Soft Touch: Low-affinity transcription factor binding sites in development and evolution. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2016, 117, 455–469.

- Levitsky, V.G.; Kulakovskiy, I.V.; Ershov, N.I.; Oshchepkov, D.; Makeev, V.J.; Hodgman, T.C.; Merkulova, T.I. Application of experimentally verified transcription factor binding sites models for computational analysis of ChIP-Seq data. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 80.

- Levitsky, V.G.; Oshchepkov, D.Y.; Klimova, N.V.; Ignatieva, E.; Vasiliev, G.V.; Merkulov, V.M.; Merkulova, T.I. Hidden heterogeneity of transcription factor binding sites: A case study of SF-1. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2016, 64, 19–32.

- Osz, J.; McEwen, A.G.; Bourguet, M.; Przybilla, F.; Peluso-Iltis, C.; Poussin-Courmontagne, P.; Mély, Y.; Cianférani, S.; Jeffries, C.M.; Svergun, D.I.; et al. Structural basis for DNA recognition and allosteric control of the retinoic acid receptors RAR–RXR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 9969–9985.

- Yin, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y. Molecular mechanism of directional CTCF recognition of a diverse range of genomic sites. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 1365–1377.

- Afek, A.; Cohen, H.; Barber-Zucker, S.; Gordân, R.; Lukatsky, D.B. Nonconsensus Protein Binding to Repetitive DNA Sequence Elements Significantly Affects Eukaryotic Genomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004429.

- Teif, V.B. Soft Power of Nonconsensus Protein-DNA Binding. Biophys. J. 2020, 118, 1797–1798.

- Yan, J.; Qiu, Y.; Ribeiro dos Santos, A.M.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.E.; Vinckier, N.; Nariai, N.; Benaglio, P.; Raman, A.; Li, X.; et al. Systematic analysis of binding of transcription factors to noncoding variants. Nature 2021, 591, 147–151.

- Slattery, M.; Zhou, T.; Yang, L.; Dantas Machado, A.C.; Gordân, R.; Rohs, R. Absence of a simple code: How transcription factors read the genome. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 39, 381–399.

- Srivastava, D.; Mahony, S. Sequence and chromatin determinants of transcription factor binding and the establishment of cell type-specific binding patterns. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2020, 1863, 194443.

- Inukai, S.; Kock, K.H.; Bulyk, M.L. Transcription factor–DNA binding: Beyond binding site motifs. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017, 43, 110–119.

- Zheng, A.; Lamkin, M.; Zhao, H.; Wu, C.; Su, H.; Gymrek, M. Deep neural networks identify sequence context features predictive of transcription factor binding. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 172–180.

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, Z.; He, Y.; Chen, Z.-H.; Li, J.; Huang, D.-S. Predicting transcription factor binding sites using DNA shape features based on shared hybrid deep learning architecture. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 24, 154–163.

- Wada, K.; Wada, Y.; Ikemura, T. Mb-level CpG and TFBS islands visualized by AI and their roles in the nuclear organization of the human genome. Genes Genet. Syst. 2020, 95, 29–41.

- Pei, G.; Hu, R.; Dai, Y.; Manuel, A.M.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, P. Predicting regulatory variants using a dense epigenomic mapped CNN model elucidated the molecular basis of trait-tissue associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 53–66.

- Jing, F.; Zhang, S.-W.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, S. An Integrative Framework for Combining Sequence and Epigenomic Data to Predict Transcription Factor Binding Sites Using Deep Learning. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2021, 18, 355–364.

- Chen, C.; Hou, J.; Shi, X.; Yang, H.; Birchler, J.A.; Cheng, J. DeepGRN: Prediction of transcription factor binding site across cell-types using attention-based deep neural networks. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 38.

More

Information

Subjects:

Genetics & Heredity

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.3K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Jun 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No