You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nimat Ullah | + 1554 word(s) | 1554 | 2021-06-17 09:55:30 | | | |

| 2 | Enzi Gong | Meta information modification | 1554 | 2021-06-25 10:45:05 | | | | |

| 3 | Nimat Ullah | + 2516 word(s) | 4070 | 2021-06-25 10:55:00 | | | | |

| 4 | Enzi Gong | -91 word(s) | 3979 | 2021-06-28 06:02:52 | | | | |

| 5 | Enzi Gong | + 746 word(s) | 4725 | 2021-06-28 06:07:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ullah, N. Food, Emotions and Behaviour Change. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11304 (accessed on 02 January 2026).

Ullah N. Food, Emotions and Behaviour Change. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11304. Accessed January 02, 2026.

Ullah, Nimat. "Food, Emotions and Behaviour Change" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11304 (accessed January 02, 2026).

Ullah, N. (2021, June 25). Food, Emotions and Behaviour Change. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11304

Ullah, Nimat. "Food, Emotions and Behaviour Change." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 June, 2021.

Copy Citation

Behaviour change techniques are considered effective means for changing behaviour, and with an increase in their use, the interest in their exact working principles has also expanded. This information is required to make informed choices about when to apply which technique. Computational models that describe human behaviour can be helpful for this. In this paper, a few behaviour change techniques have been connected with a computational model of emotion and desire regulation. Simulations have been performed to illustrate the effect of the techniques. The results demonstrate the working mechanisms and feasibility of the techniques used in the model.

desire regulation

emotion regulation

behaviour change techniques

mental health

physical health

BCTs

1. Introduction

Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) [1][2] provide a strong basis for changing one’s behaviour to promote healthy lifestyles. These techniques are used as interventions for changing specific undesired behaviours, for instance, to ensure healthy eating and physical activity [3][4], mood regulation, and the avoidance of excessive use of drugs, etc. Although the techniques are broadly applied, their exact working remains vague. However, from another perspective, some of the techniques listed as BCTs [2] are somehow already known to us. For instance, the generation and regulation of emotions has quite extensively been explained by Gross [5]. Similarly, the interplay of emotions and desires has also been thoroughly explored by various scholars, for instance [6][7][8]. These findings from relatively different disciplines, therefore, provide very sound ground for the amalgamation of these perspectives.

Definitions from within the behavioural sciences show the effects of certain specific interventions clearly, however, understanding how an intervention does what it does is often not so clear. On the other hand, from the social sciences such as psychology, we have an understanding of how some of the more commonly used emotion regulation strategies work. Some of these same strategies also form part of the BCTs used in this model, as given below in Table 1. For instance, the intervention called ‘regulation of negative emotions’, from behavioural science, employs the same emotion regulation strategies that are defined in psychology. Thus, to fill this gap, in this paper these two different fields have been brought together with the help of computational modelling. The model therein demonstrates the working mechanism of the BCTs used in this model and illustrates how they helps in changing unhealthy behaviours in terms of eating. Hence, as with other such models, this model is also considered a behaviour change model. Moreover, the model tries to reduce the negative impact of the interplay between different negative emotions, i.e., anxiety and food desires.

Table 1. Relevant coded interventions and their descriptions.

| S. # | BCTs | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Information about health consequences [5.1] | Provide information (e.g., written, verbal, visual) about the health consequences of performing the behaviour |

| 2. | Reduce negative emotions [11.2] | Advise on ways of reducing negative emotions to facilitate the performance of the behaviour |

| 3. | Stress management [11.2] | Advise on ways of reducing stress |

| 4. | Problem solving/coping planning [1.2] | Analyse, or prompt the person to analyse, factors influencing the behaviour and generate or select strategies that include overcoming barriers and/or increasing facilitators (includes ‘relapse prevention’ and ‘coping planning’) |

| Goal setting (outcome) [1.3] | Set or agree on a goal defined in terms of a positive outcome of wanted behaviour | |

| Goal setting (behaviour) [1.1] | Set or agree on a goal defined in terms of the behaviour to be achieved |

In the remainder of this paper, the related work is divided into two sections. Section 2 discusses the interplay of emotion and desire and its regulation, and Section 3 describes the BCTs used in this paper. Section 4 provides a brief overview of the modelling technique used for the model developed in this paper. Section 5 introduces the computational model and Section 6 gives a detailed explanation of the simulation results. The paper is finally concluded in Section 7.

2. The Interplay and Regulation of Emotions and Desires

Emotions are considered as drivers of action, [9] however, at the same time, emotions themselves can also be result of other actions, for instance, binging [10] can cause an emotional response. Similarly, binging, or in other words overeating, can be a trigger as well as a response to emotions [11] which can be considered as an impediment between the optimal response to the environment and emotions [8]. This interplay between emotions and desires [12] can have very negative psychological as well as physical health [13][14] consequences as both can prove triggers for one another [10][12][15] and form a continuous cycle. To avoid such a cycle [12][16], a person must have the ability to regulate their emotions and desires and do not let emotions or desires influence each other.

Various strategies can be used for the regulation of emotions and desires, however the adaptivity of these strategies is purely dependent on the context in which they are employed [17][18]. In the model developed in this paper (explained in Section 5), reappraisal, situation modification, and problem solving have been used for the regulation of the negative emotions because of the way they deal with negative emotions and also because these strategies are more adaptive as compared to other similar strategies. For instance, reappraisal is considered quite an adaptive strategy [8] and remains so even if the intensity of the negative emotions/desires is low. This is because the reappraisal of low intensity emotions requires the activation of fewer brain parts as compared to high intensity emotions [19][20]. Therefore, the model employs reappraisal only for low intensity negative emotions. Similarly, situation modification is considered a better option in a situation which induces a high intensity of negative emotions or desires [20]. The third strategy used in the model in this paper is problem solving. This strategy is also considered an adaptive strategy as it suggests the solving of the problem that is causing the negative emotions [21]. Therefore, both of these strategies are activated only for the hinderance of high intensity negative emotions whilst considering their efficacy in their respective situations. The question remains, however, as to how best to use these techniques/strategies. An answer to this question can be found from within behavioural sciences.

3. Behaviour Change Interventions

According to [22] behaviour itself refers to ‘anything a person does in response to internal or external events. Actions may be overt (motor or verbal) and directly measurable, or covert (e.g., physiological responses) and only indirectly measurable; behaviours are physical events that occur in the body and are controlled by the brain’. BCTs, on the other hand, are the smallest components that are thought to bring the proposed change in one’s behaviour, either alone or in combination with other BCTs [23], and behaviour change intervention refers to the application of these BCTs. Behaviour is also considered an outcome of an intervention [24]. A universally agreed upon list of 93 distinct BCTs has been developed as taxonomy v1 in [2], where each of which, alone or in combination with others, can be used as an intervention. However, as the underlying mechanisms are not always clear, it is sometimes difficult to decide which BCTs to use as interventions under specific circumstances. Similarly, developing an intervention itself is a very complex process as it can have many BCTs and the definition of its active, effective components is a challenge [2].

In the recent years, some scholars have identified interventions for some behaviours, for instance, [3] short list interventions for increasing physical activity and healthy eating, [25] for smoking cessation, [26] for safe drinking, and [27] for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections, etc. The purpose of this discussion is to highlight the importance of the development of well-specified interventions [2]. Although it is a difficult task to specify which BCT or combination of BCTs will work the best, for whom, and in which specific situation, the suitability of the interventions used in this paper has been decided on the basis of their definitions as stated in [2][4] and used in different studies regarding similar behavioural goals, as mentioned above. Table 1 below provides list of the BCTs used as interventions in the model in this paper and their descriptions.

4. Networking-Oriented Modelling Technique

The computational model that will be presented in this paper is based on a network-oriented temporal-causal network modelling technique [28], see also [29]. In this technique, the phenomenon is represented as a network whereby each node has some characteristic which varies over time. Each node X is connected to another node Y through a connection which carries causal impact from X to Y. This defines the causal impact exerted by X on Y over time. Here a model can be represented as a labelled graph where:

-

Each connection carries some weight ωX,Y. from state X to state Y called casual impact;

-

Multiple incoming causal impacts ωX,YX(t) to state Y from some states X are aggregated using combination function cY(.);

-

There exists a notion of speed of change of each state to define how fast a state changes because of the incoming impact (speed factor ηY).

These three characteristics define the temporal-causal network. An explanation of these terms and their numerical representation is given below in the upper and lower parts of Table 2, respectively.

Table 2. Basics of a temporal-causal network model.

| Concept | Conceptual Representation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| States and connections | X, Y, X→Y | Describes the nodes and links of a network structure (e.g., in graphical or matrix form) |

| Connection weight | ωX,Y | The connection weight ωX,Y usually in [–1,1] represents the strength of the causal impact of state X on state Y through connection X→Y |

| Aggregating multiple impacts on a state | cY(.) | For each state Y a combination function cY(.) is chosen to combine the causal impacts of other states on state Y |

| Timing of the effect of causal impact | ηY | For each state Y a speed factor ηY ≥ 0 is used to represent how fast a state is changing upon causal impact |

| Concept | Numerical Representation | Explanation |

| State values over time t | Y(t) | At each time point t, each state Y in the model has a real number value, usually in [0,1] |

| Single causal impact | impactX,Y(t) = ωX,Y X(t) | At t state X with a connection to state Y has an impact on Y, using connection weight ωX,Y |

| Aggregating multiple causal impacts | aggimpactY(t) = cY(impactX1,Y(t),…, impactXk,Y(t)) = cY(ωX1,YX1(t), …, ωXk,YXk(t)) |

The aggregated causal impact of multiple states Xi on Y at t, is determined using combination function cY(.) |

| Timing of the causal effect | Y(t+Δt) = Y(t) + ηY [aggimpactY(t) − Y(t)] Δt = Y(t) + ηY [cY(ωX1,YX1(t), …, ωXk,YXk(t)) − Y(t)] Δt |

The causal impact on Y is exerted over time gradually, using speed factor ηY; here the Xi are all states with outgoing connections to state Y |

Besides the generation of automatic numerical equations by the dedicated software, available at https://www.researchgate.net/project/Network-Oriented-Modeling-Software (accessed on 5 April 2021), this approach provides a library of, currently, over 40 combination functions which can be used for the aggregation of multiple incoming causal impacts. Not only may a composition of the available combination functions be used, self-defined functions can also be added to the library. This makes this technique very flexible and user friendly.

5. Computational Model

The model introduced in this section is developed using the concepts discussed above using the network-oriented temporal-causal modelling technique discussed in the preceding section. Motivation for this model comes from [16], in which a person has to choose a bad situation in order to get rid of a worse situation. In this model, the BCTs listed in Table 1 have been used as interventions to help the person change their behaviour and hence adopt a healthy lifestyle. The nomenclature of the states is provided in Table 3 below, where each of the comma-separated alphabets and letters in the subscript represent a state name. For instance, ws(s, g.o, anx) represents wss, wsg.o, wsanx.

Table 3. Nomenclature of the states used in the model.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| ws(s, g.o, anx) | World state for stimulus ‘s’, goal setting (outcome) ‘g.o’, anxiety ‘anx’ |

| ss(s, b−, b+, g.o, g.b, b.strs, b.anx) | Sensor state for stimulus ‘s’, negative body state ‘b−’, goal outcome ‘g.o’, goal behaviour ‘g.b’, body stress ‘b.strs’, body anxiety ‘b.anx’ |

| srs(s, b−, b+, g.o, g.b, b.strs, b.anx) | Sensor representation state for stimulus ‘s’, negative body state ‘b−’, positive body state ‘b+’, goal outcome ‘g.o’, goal behaviour ‘g.b’, body stress ‘b.strs’, body anxiety ‘b.anx’ |

| fs(b−, b+, g.b, b.strs, b.anx) | Feeling state for body state ‘b−’, goal behaviour ‘g.b’, stress ‘b.strs’, anxiety ‘b.anx’ |

| ps(a, b−, b+, g.o, g.b, b.strs, b.anx) | Preparation state for action ‘a’, body state ‘b−’, body state ‘b+’, goal outcome ‘g.o’, goal behaviour ‘g.b’, body stress ‘b.strs’, body anxiety ‘b.anx’ |

| es(a, b−, b+, g.o, g.b, b.strs, b.anx) | Execution state for action ‘a’, body state ‘b-’, body state ‘b+’, goal outcome ‘g.o’, goal behaviour ‘g.b’, body stress ‘b.strs’, body anxiety ‘b.anx’ |

| dss | Desire state for stimulus ‘s’ |

| bs(+, −, strs.−, anx.−) | Belief state for positive ‘+’, negative ‘−’, negative stress ‘strs.−’, and negative anxiety ‘anx.−’ beliefs |

| cs(reapp, e.reapp, d-s.m, e-p.solv) | Control state for (desires) reappraisal ‘reapp’, (emotion) reappraisal ‘e.reapp’, (desire) situation modification ‘d-s.m’, (emotion) problem solving ‘e-p.solv’ |

| Ia,b,c(r.n.e, strs.mgt, inf.beh) | Intervention ‘a’ for regulation of negative emotions ‘r.n.e’, ‘b’ for stress management ‘strs.mgt’, ‘c’ for information about health consequences ‘inf.beh’ |

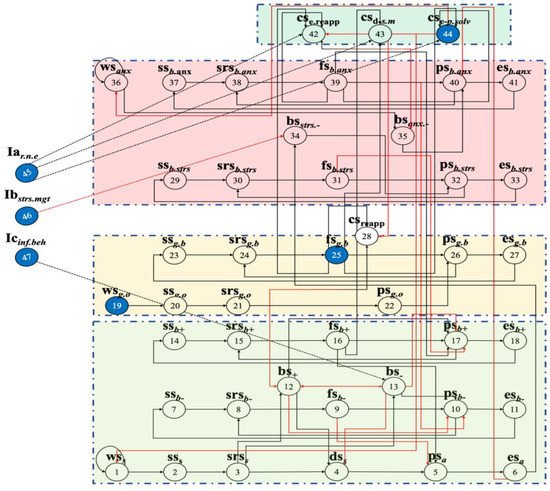

The computational model in Figure 1 introduces interventions for changing negative behaviours in terms of mental and physical health, i.e., emotions and food desires. The lower part represents food-related desire generation and its regulation with the help of interventions, the second part, enclosed in yellow for ease of explanation, represents an intervention called ‘goal setting (outcome)’ wsg.o, which activates another intervention called ‘goal setting (behaviour)’, the feeling state represented by fsg.b. The upper pink part implements emotion generation and regulation with the help of interventions. Moreover, the last three states, grouped together, are the states used for regulation. The colours in the model differentiate between the different interacting components of the model. For instance, the lower light green coloured part of the model has all the states involved in the generation and regulation of food desire, the second light yellow colour represents the states involved in goal setting (outcome and behaviour) which are basically interventions, the states in the pink colour represent the generation and regulation of negative emotions. The states in the topmost green colour represent the emotion and desire regulation strategies that are activated by the intervention ‘a’ called ‘regulation of negative emotions’, i.e., Iar.n.e.

Figure 1. Computational behaviour change model for food desires (lower light green) and negative emotions (pink) through BCTs (all other colours).

The first state, wss, represents the world state for some food-related stimulus which arouses a person’s desire, dss, for eating. A person, in a given situation, can have positive bs+ or negative belief bs- about food which can increase or decrease the desire of the person to eat or not to eat the food. The physical action, i.e., eating is represented by preparation state for action ‘a’ psa and execution state for action ‘a’ esa. The two positive and negative body loops serve as feedback to the internal body preparation psb(+/a−) and the execution for actions esb(+/−) as explained by Damasio [30]. The regulation of these negative and positive beliefs and feelings about the food is carried out through the control state for reappraisal csreapp which tries to change the positive belief of the person about the food into a negative belief by reappraising the food and its contribution to the person’s health.

The second part, as mentioned earlier, represent the outcome and behavioural goals. Everyone has certain health-related goals for themselves. These goals activate behaviour that can help the person to achieve these goals. In this model, the preparation state for goals (outcome) psg.o activates the preparation state for goals (behavioural) psg.b. These behavioural goals activates the means to achieve the outcome goals, therefore, fsg.b helps in activating all the means (strategies) to some extent for handling the various situations explained in the simulations below, irrespective of whether these strategies are for desire regulation or emotion regulation.

In the third pink portion of the model, wsanx represents the stimulus in which the person has a negative belief about bsanx.−causing them to become anxious. This anxiety also has effect on the food desires of the person. If the person is feeling a high intensity of anxiety, they will also have a tendency towards (over) eating. According to [31] some people tend to use eating as a strategy against negative emotions. Therefore, fsanx has a positive connection to ps+. Thus, in this model, the negative belief towards the anxiety-provoking stimulus is reappraised by the control state for (emotions) reappraisal cse.reapp. Similarly, the control state for (emotions) problem solving cse-p.solv is used for solving the problem that causes the negative emotions, i.e., anxiety in this model. In the model this control state cse-p.solv has a negative connection to wsanx resulting in the emotion eliciting problem being solved in the real world. Moreover, the control state for (desires) situation modification, csd-s.m, modifies the situation in which there exists a food desire eliciting stimulus, i.e., the tempting food, in this model represented by wss.

6. Simulation Results

The simulation results below demonstrate the various what-if scenarios provided in Table 4. The following situation has been simulated to provide a better understanding of the simulation results.

Table 4. Initial values of the key states and expected simulation results.

| S. # | Interventions | Stimulus | Behaviour | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wsg.o | Icinf.beh | Iar.n.e | Ibstrs.mgt | wss | wsanx | Strategies | |

| 1. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | Reappraisal of food desire fails (lack of information) |

| 1 | Reappraise food desire | ||||||

| 2. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Reappraisal fails: eat food ←→ feel stressed |

| 1 | Efficiently manages stress after eating | ||||||

| 3. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | Reappraise food desires only but also feel anxiety |

| 1 | Reappraises both food desire and anxiety | ||||||

| 4. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Reappraisal fails: eat food←→feel stressed |

| 1 | Reappraisal fails: eat food←→feel stressed. Hence, stress management and situation modification (food) and problem solving (emotions) leads to stable situation | ||||||

Anna wants to lose/maintain her weight to look attractive, however she is unable to do so because of her current lifestyle. Her physician cum dietitian sets some behaviour change interventions for her to ensure her goals are achieved. First, she is provided with information about the health consequences of her current lifestyle which should enable her to deal with low intensity temptation towards food. Second, she is taught stress management strategies, as she goes into a stress and binging cycle every time she fails to reappraise her food desires. Moreover, she also sometimes feels anxiety of varying intensities. For this, she is taught to regulate her negative emotions in order to help her to avoid overeating. In case of high intensity negative emotions and high intensity tempting food, she is taught other strategies, namely problem solving and situation modification, respectively.

Table 4 below gives the combination of initial values of all the intervention states. Initial values of all the other states were kept zero. Other parameter values are provided in the tables in Appendix A and Appendix B. These values are essential for the reproduction of the results through this model.

In the simulation results below, it is assumed that the person has already set some outcome goals for themselves. The outcome goals activate the behavioural goals, which in turn activate the means to achieve said goals [32]. Further, the simulation results are explained in detail below.

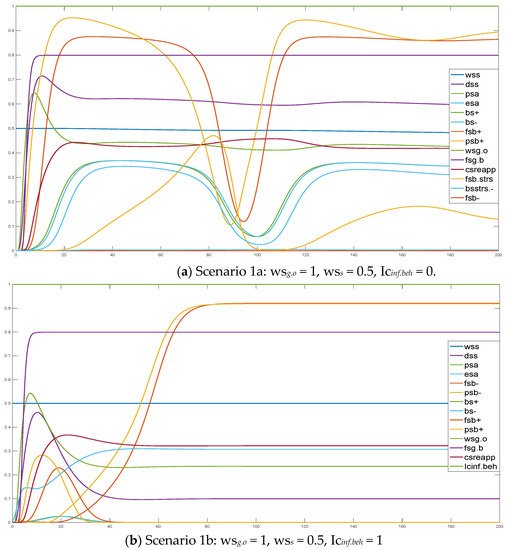

Figure 2a represents a scenario in which the subject has not yet been provided with any information, Icinf.beh, about the consequences of their current lifestyle/behaviour. In the simulation results it can be seen that, although, the person tries to reappraise csreapp their desire for food, they fail. As a result, a physical action, psa and esa, takes place that represents eating. After eating, they realize that they were not supposed to eat (due to dietary plans) and further become stressed fsb.strs. This can cause serious health consequences if the person feels a high intensity of post-eating stress, as this cycle can become longer and longer.

Figure 2. (a) Failure of reappraisal in the absence of information on health consequences. (b) Successful reappraisal of food desires after providing information on health consequences as an intervention.

Figure 2b demonstrates a scenario in which the person has been provided with information about the health consequences, Icinf.beh, of their current behaviour. It can be seen that initially the person’s desire state, dss, and positive belief, bs+, about the food is quite high, however this starts to decrease as soon as the control state for reappraisal csreapp is activated. Reappraisal changes the person’s belief about the food, therefore, the negative belief bs- of the person regarding the food increases and the positive belief bs+ decreases. Hence, the desire for food dss also decreases. The information about health consequences provided to the person has enabled them to effectively reappraise them beliefs and not eat the food.

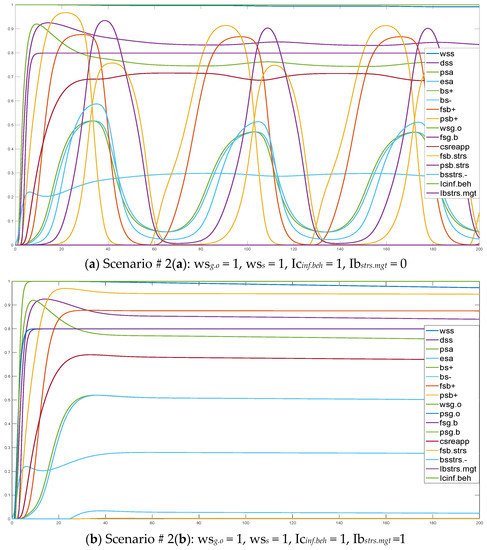

Figure 3a gives insight into a scenario where a person has information about the health consequences of their behaviour but in case of high intensity tempting food, they fails to regulate their desire and eat the food. Due to this, the person feels stressed. To overcome the stress, the person again decides to eat, and the cycle continues. For instance, in Figure 3 it can be seen that the positive belief bs+ and the desire dss of the person for food are high until the end of the graph. In the other curves, the preparation and execution of the physical action, i.e., eating is represented by the psa and esa. It can be seen that just after the physical action, i.e., eating, the stressful feelings fsb.strs increase. The fluctuation in the graph shows the interplay between these two states, i.e., eating and feeling stressful because of eating and again eating to overcome the stress, and so on.

Figure 3. (a) Tempting food inducing the stress-eating cycle. (b) Breaking the tempting food-induced stress-eating cycle through a ‘stress management’ intervention.

Figure 3b demonstrates the same scenario as the previous figure with an extra intervention called stress management, Ibstrs.mgt, that helps the person regulate their stress after eating to break the cycle. For instance, as in previous figure, the positive belief, bs+, and the desire, dss, of the person for food are high until the end of the graph, indicating that the person is unable to regulate their desires. In this figure, it can be seen that although the person also eats the food, i.e., the preparation and execution of the physical action psa and esa takes place, the person does not become stressed due to the effect of the stress management intervention Ibstrs.mgt. The curve just above the base horizontal line is the negative belief, bsstrs.−, of the person about the eating action, esa, which causes stress, however the intensity is very low and thus this does not cause any stress for the person.

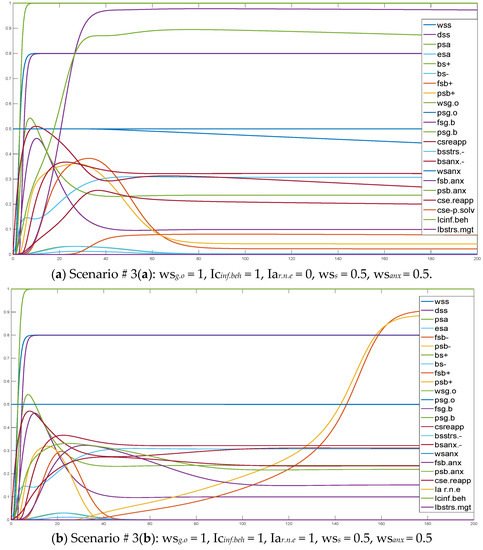

The simulation result in Figure 4a demonstrates a scenario in which the person has been educated about the health consequences of their behaviours but has not been guided about the regulation of negative emotions. In this scenario, the person is able to regulate their low intensity food desires, dss, but not their anxiety, fsanx. As the figure shows, initially the positive belief, bs+, and desire, dss, of the person for food is high, however negative beliefs, bs_, about the food increase as soon as the person starts reappraising, csreapp. This also decreases their desire for food, dss. On the contrary, the reappraisal of negative emotions, fsanx, fails as the person has not been given the ‘negative emotion regulation’ intervention.

Figure 4. (a) Success in low intensity desire regulation but failure in emotion regulation. (b) Success in low intensity desire and emotion regulation.

Figure 4b depicts a scenario in which the person has been given two interventions, namely ‘providing information on consequence’, Icinf.beh, of the behaviours that the person is currently practicing and ‘regulation of negative emotions’, Iar.n.e. These two interventions help the person regulate their food desire and anxiety. For instance, in the figure it can be seen that initially the desire, dss, and positive belief of the person about the food is high. Similarly, the negative anxious belief, bsanx.−, is also high. All these states decrease after the activation of their respective control states for reappraisals, i.e., csreapp and cse-re.reapp, respectively. Finally, the negative belief, bs-, about the food increases which, in turn, also increases the negative feelings in the body regarding the food, fsb−.

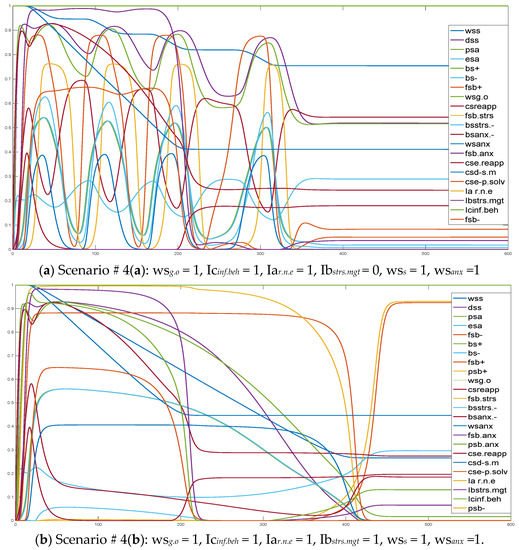

In Figure 5a, the person has been given all the interventions modelled here except stress management, Ibstrs.mgt. This figure shows that the person faces high intensity tempting food, wss, and anxiety, wsanx, at the same time. Initially, the person tries to reappraise their beliefs about both the stimuli, for instance, csreapp tries to reappraise their belief about the food, wss, and cse.reapp tries to reappraise their belief about the stimulus causing them anxiety, wsanx. On contrary, as reappraisal is not very effective for high intensity stimuli, therefore, the person fails. This makes the person eat the food, psa and esa. The eating of the food increases the person’s negative beliefs about eating and makes the person feel stressed fsb.strs. The fluctuations in this figure represent the phenomenon in which the person feels stressed as they ate and then subsequently eats because they are stressed. This cycle goes on until the second strategy of the intervention called ‘regulation of negative emotions’ Iar.n.e shows its effect. It enables the person to leave the tempting food environment, wss, through a regulation strategy called situation modification, as represented by the control state for situation modification (for desire) csd-s.m. It also enables the strategy that encourages the person to go to solve the problem cse-p.solv (control state for problem solving for emotions) that is causing the anxiety wsanx. This makes the person finally arrive in a mentally stable situation in the absence of stress management intervention, Ibstrs.mgt.

Figure 5. (a) Lack of stress management but eventually stable. (b) Avoiding anxiety-induced overeating through multiple interventions.

In Figure 5b the person deals with the same situation as in the previous figure, with the exception the ‘stress management’ Ibstrs.mgt has been used as an intervention here. In the previous scenario, the person goes into stress-eating cycles. In the figure under discussion, the person efficiently manages their stress and implements the two strategies for emotion and desire regulation, i.e., cse-p.solv and csd-s.m. In contrast to the previous figure, here the person also develops a negative belief, bs_, and negative body feelings, fsb_, about eating within that situation, i.e., under a high intensity of negative emotions and food desire.

7. Discussion

This paper introduces a computational network model which brings findings and techniques from different disciplines together into a single network-oriented temporal-causal model. Unhealthy emotions, emotional eating, and food desires and their adverse consequences, on the one hand, are proven facts in social, cognitive, and behavioural sciences. BCTs, on the other hand, are expected to help in changing any such unwanted/unhealthy behaviour. This endeavour has, therefore, illustrated how the BCTs could work in terms of desire and emotion regulation, as interventions for avoiding unhealthy negative behaviours. The working and expected results of these interventions have been shown through simulation results. The simulations give a comparative picture of the expected results with and without certain interventions.

The novelty of the model lies in the fact that it applies BCTs to negative emotions such as food desire and anxiety, simultaneously, in a computational model for the first time, where the model not only helps in disintegrating the interplay between these two different kinds of emotions but also assists in overcoming their consequences. This, apart from helping in understanding the negative outcomes of the interactions of these two emotions, also helps in avoiding their negative impact within our daily lives. Moreover, the understanding of this mechanism also creates solid ground for digitizing interventions for these types of negative emotions and adapting the same in a clinical setup for in-depth personalized analysis against real time data. Therefore, in future, the authors aim at developing a system in which certain BCTs are recommended on the basis of the computational model presented in this paper. This potential system will help guide users to the most suitable BCT depending on their condition. The same can further be made intelligent by employing AI techniques which will not only make this system personalized but also adaptive for validation against real time data.

References

- Michie, S.; Wood, C.E.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.J.; Hardeman, W. Behaviour Change Techniques: The Development and Evaluation of a Taxonomic Method for Reporting and Describing Behaviour Change Interventions (a Suite of Five Studies Involving Consensus Methods, Randomised Controlled Trials and Analysis of Qualitative Da. Health Technol. Assess. 2015, 19, 1–188.

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95.

- Michie, S.; Abraham, C.; Whittington, C.; McAteer, J.; Gupta, S. Effective Techniques in Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Interventions: A Meta-Regression. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 690–701.

- Michie, S.; Ashford, S.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Dombrowski, S.U.; Bishop, A.; French, D.P. A Refined Taxonomy of Behaviour Change Techniques to Help People Change Their Physical Activity and Healthy Eating Behaviours: The CALO-RE Taxonomy. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1479–1498.

- Gross, J.J. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299.

- Evers, C.; Dingemans, A.; Junghans, A.F.; Boevé, A. Feeling Bad or Feeling Good, Does Emotion Affect Your Consumption of Food? A Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 92, 195–208.

- Schuster, M.J. Consumers’ Feelings of Guilt as a Function of Snack Type. EC Nutr. 2017, 6, 291–297.

- De Ridder, D.; Evers, C. Affective Determinants of Health Behavior; Williams, D.M., Rhodes, R.E., Conner, M.T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 1.

- Ekman, P. An Argument for Basic Emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200.

- Macht, M.; Dettmer, D. Everyday Mood and Emotions after Eating a Chocolate Bar or an Apple. Appetite 2006, 46, 332–336.

- Yeomans, M.R.; Coughlan, E. Mood-Induced Eating. Interactive Effects of Restraint and Tendency to Overeat. Appetite 2009, 52, 290–298.

- Aldao, A.; Sheppes, G.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation Flexibility. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2015, 39, 263–278.

- Suri, G.; Sheppes, G.; Young, G.; Abraham, D.; McRae, K.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation Choice: The Role of Environmental Affordances. Cogn. Emot. 2018, 32, 963–971.

- Gross, J.J. Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- Boon, B.; Stroebe, W.; Schut, H.; Jansen, A. Food for Thought: Cognitive Regulation of Food Intake. Br. J. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 27–40.

- Ullah, N.; Treur, J. The Choice Between Bad and Worse: A Cognitive Agent Model for Desire Regulation Under Stress. In Principles and Practice of Multi-Agent Systems. PRIMA 2019; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Baldoni, M., Dastani, M., Liao, B., Sakurai, Y., Zalila Wenkstern, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11873, pp. 496–504.

- Ullah, N.; Treur, J.; Koole, S.L. A Computational Model for Flexibility in Emotion Regulation. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual International Conference on Biologically Inspired Cognitive Architectures, BICA 2018, Prague, Czech Republic, 22–24 August 2018; Samsonovich, A.V., Lebiere, C.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 145, pp. 572–580.

- Ullah, N.; Koole, S.L.; Treur, J. Take It or Leave It: A Computational Model for Flexibility in Decision-Making in Downregulating Negative Emotions. In Proceedings of the International Conferenec on Intelligent Computing, ICIC’20, Bari, Italy, 2–5 October 2020; De-Shuang, H., Kang-Hyun, J., Eds.; Springer Notes in Computer Science. Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. 12.

- Silvers, J.A.; Weber, J.; Wager, T.D.; Ochsner, K.N. Bad and Worse: Neural Systems Underlying Reappraisal of High- and Low-Intensity Negative Emotions. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2015, 10, 172–179.

- Van Bockstaele, B.; Atticciati, L.; Hiekkaranta, A.P.; Larsen, H.; Verschuere, B. Choose Change: Situation Modification, Distraction, and Reappraisal in Mild versus Intense Negative Situations. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 583–596.

- Billings, A.G.; Moos, R.H. The Role of Coping Responses and Social Resources in Attenuating the Stress of Life Events. J. Behav. Med. 1981, 4, 139–157.

- Davis, R.; Campbell, R.; Hildon, Z.; Hobbs, L.; Michie, S. Theories of Behaviour and Behaviour Change across the Social and Behavioural Sciences: A Scoping Review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 323–344.

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M. Behavior Change Techniques. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 182–187.

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M. Theories and Techniques of Behaviour Change: Developing a Cumulative Science of Behaviour Change. Health Psychol. Rev. 2012, 6, 1–6.

- Michie, S.; Hyder, N.; Walia, A.; West, R. Development of a Taxonomy of Behaviour Change Techniques Used in Individual Behavioural Support for Smoking Cessation. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 315–319.

- Michie, S.; Whittington, C.; Hamoudi, Z.; Zarnani, F.; Tober, G.; West, R. Identification of Behaviour Change Techniques to Reduce Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Addiction 2012, 107, 1431–1440.

- De Vasconcelos, S.; Toskin, I.; Cooper, B.; Chollier, M.; Stephenson, R.; Blondeel, K.; Troussier, T.; Kiarie, J. Behaviour Change Techniques in Brief Interventions to Prevent HIV, STI and Unintended Pregnancies: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204088.

- Treur, J. Network-Oriented Modeling for Adaptive Networks: Designing Higher-Order Adaptive Biological, Mental and Social Network Models; Studies in Systems Decision and Control; Kacprzyk, J., Ed.; Springer Nature Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 251.

- Treur, J. Network-Oriented Modeling; Understanding Complex Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016.

- Damasio, A.R. Emotion in the Perspective of an Integrated Nervous System1Published on the World Wide Web on 27 January 1998. Brain Res. Rev. 1998, 26, 83–86.

- Heatherton, T.F.; Baumeister, R.F. Binge Eating as Escape from Self-Awareness. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 86–108.

- Ullah, N.; Treur, J. How Motivated Are You? A Mental Network Model for Dynamic Goal Driven Emotion Regulation. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing, ICAISC’20, Online Conference, 12–14 October 2020.

More

Information

Subjects:

Engineering, Civil

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

923

Revisions:

5 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Jun 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No