| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Riccardo Dalle Grave | + 1016 word(s) | 1016 | 2020-06-17 14:46:34 | | | |

| 2 | Riccardo Dalle Grave | + 1016 word(s) | 1016 | 2020-06-17 20:23:50 | | | | |

| 3 | Riccardo Dalle Grave | + 1015 word(s) | 1015 | 2020-06-17 20:34:24 | | | | |

| 4 | Lily Guo | -16 word(s) | 999 | 2020-10-27 04:55:58 | | | | |

| 5 | Lily Guo | Meta information modification | 999 | 2020-10-27 05:00:24 | | |

Video Upload Options

Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy, also known as CBT-E, is a “transdiagnostic” psychological treatment for all forms of eating disorder including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder and other similar states. CBT-E is the only treatment recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for all the forms of eating disorders both for adults and adolescents

1. Introduction

Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy, also known as CBT-E, is a “transdiagnostic” psychological treatment for all forms of eating disorder including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder and other similar states. CBT-E was devised by Christopher Fairburn and colleagues in Oxford [1][2], but then it was adapted by Dalle Grave and colleagues also for younger people [3] and for day patients and inpatients [4].

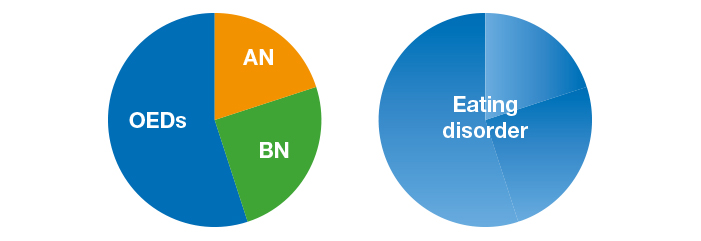

2. The Transdiagnostic View of Eating Disorders

The transdiagnostic view on the processes that maintain eating disorder psychopathology [1] is based on the observation that the main maintaining processes are likely to be largely the same across different eating disorder diagnoses (Figure 1). Therefore, if these maintaining processes can be disrupted in one eating disorder it should be possible to disrupt them in other eating disorders. Hence the Centre for Research on Eating Disorders at Oxford (CREDO) team reconceptualised the existing evidence-based form of CBT for bulimia nervosa and adapted it to make it suitable for all forms of eating disorders. The result was the development of a new transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural treatment called CBT-E.

3. Phases of the Treatment

When working with people who are not significantly underweight, CBT-E generally involves an initial assessment appointment followed by 20 treatment sessions over 20 weeks, lasting 50-minutes each.

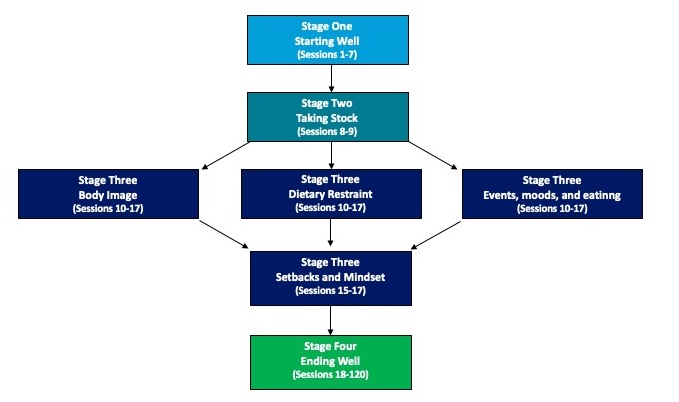

CBT-E isn’t a “one-size-fits-all” treatment. CBT-E is a highly individualised treatment. The therapist creates a specific version of CBT-E to match the exact eating problem of the person receiving treatment. CBT-E has four stages (Figure 2).

Figure 2. CBT-E Map for not underweight patients BMI 18.5 -39.9 (20 weeks – 20 sessions)

Stage One, the focus is on gaining a mutual understanding of the person’s eating problem and helping him or her to modify and stabilise their pattern of eating. There is also emphasis on personalised education and the addressing of concerns about weight. It is best if these initial sessions are twice a week.

In the brief second stage, progress is systematically reviewed and plans are made for the main body of treatment (Stage Three).

Stage Three consists of a run of weekly sessions focused on the processes that are maintaining the person’s eating problem. Usually, this involves addressing concerns about shape and eating; enhancing the ability to deal with day-to-day events and moods; and addressing of extreme dietary restraint.

Towards the end of Stage Three and in Stage Four the emphasis shifts onto the future. There is a focus on dealing with setbacks and maintaining the changes that have been obtained.

Generally, a review session is held some months after treatment has ended. It provides an opportunity for a review of progress and the addressing of any problems that remain or have emerged.

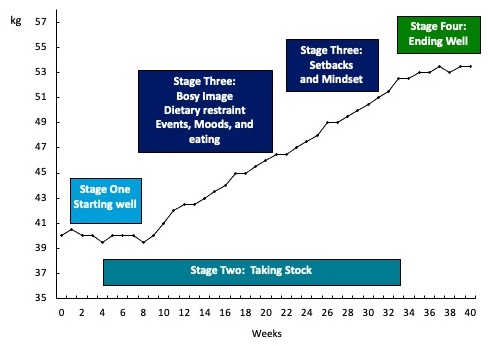

With people who are underweight, treatment needs to be longer, often involving around 40 sessions over 40 weeks. In this version of CBT-E, weight regain is integrated with addressing eating disorder psychopathology in three steps (Figure 3). Before embarking on weight regain, patients and therapists spend the first weeks of this treatment carefully considering the reasons for and against this change. The goal in CBT-E is that patients themselves decide to regain weight rather than having this decision imposed upon them. During the final step of weight regain the patient becomes accomplished at maintaining their weight.

4. Forms of Treatment

CBT-E can be delivered in two forms: (i) a “focused” form, which exclusively addresses the eating disorder psychopathology; or (ii) a “broad” form, which also addresses one or more of the following “external” maintaining mechanisms: clinical perfectionism, core low self-esteem, marked interpersonal difficulties.

The focused form is indicated for most patients and should be viewed as the default version. With most patients, it is more effective than the broad version and it is easier to implement. The broad form should be reserved for patients who (i) have a pronounced form of one of the “external” maintaining mechanisms to core eating disorder psychopathology and (ii) where this mechanism appears to be contributing to the maintenance of the eating disorder. The decision to use the broad form is taken during a review session in Stage Two, as by then the therapist knows the patient reasonably well and barriers to change will be becoming clear.

5. The Current Status of CBT-E

If one focuses on studies in which CBT-E was delivered well, the evidence suggests that with patients who are not significantly underweight about two-thirds of those who start treatment make a full recovery. This recovery appears to be well-maintained. Many of the remainders have also improved but not to this extent. The response rate is somewhat lower in patients who are substantially underweight and fewer complete treatment.

As matters stand, the research findings may be summarised as follows:

- CBT-E has been shown to be suitable for all forms of eating disorder encountered in adults [5][6].

- CBT-E has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of younger patients [7][8].

- CBT-E may be used in inpatient and day-patient settings with promising results [9].

- In a direct comparison with a leading alternative psychological treatment for not underweight adults, interpersonal psychotherapy or IPT, CBT-E was found to be more potent [10]. CBT-E it has been also found to be more effective than psychoanalytic psychotherapy [11].

- CBT-E has been shown similar efficacy than: Specialist Supportive Clinical Management, Maudsley Model Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults in underweight adults [12].

CBT-E is the only treatment recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for all the forms of eating disorders both for adults and adolescents.

More information about CBT-E can be found at the official CBT-E website

References

- Christopher G Fairburn; Zafra Cooper; Roz Shafran; Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment ?. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2003, 41, 509-528, 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8.

- Christopher G Fairburn. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders; Guilford Press: New York, 2003; pp. 45-193.

- Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S.. Cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with eating disorders.; Guilford Press: New York, 2020; pp. 304.

- Dalle Grave, R.. Intensive cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders; Nova: Hauppauge, NY, 2012; pp. 259.

- Christopher G Fairburn; Zafra Cooper; Helen A. Doll; Marianne E. O’Connor; Kristin Bohn; Deborah M. Hawker; Jackie A. Wales; Robert L. Palmer; Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up.. American Journal of Psychiatry 2008, 166, 311-9, 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608.

- Christopher G Fairburn; Zafra Cooper; Helen A. Doll; Marianne E. O'connor; Robert L. Palmer; Riccardo Dalle Grave; Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with anorexia nervosa: A UK–Italy study. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2012, 51, R2-8, 10.1016/j.brat.2012.09.010.

- Riccardo Dalle Grave; Simona Calugi; Helen A. Doll; Christopher G Fairburn; Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: An alternative to family therapy?. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2012, 51, R9-R12, 10.1016/j.brat.2012.09.008.

- Riccardo Dalle Grave; Massimiliano Sartirana; Simona Calugi; Enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: Outcomes and predictors of change in a real-world setting.. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2019, 52, 1042-1046, 10.1002/eat.23122.

- Riccardo Dalle Grave; Simona Calugi; Maddalena Conti; Helen Doll; Christopher G. Fairburn; Inpatient cognitive behaviour therapy for anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial.. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 2013, 82, 390-8, 10.1159/000350058.

- Christopher G Fairburn; Suzanne Bailey-Straebler; Shawnee Basden; Helen A. Doll; Rebecca Jones; Rebecca Murphy; Marianne E. O'connor; Zafra Cooper; A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders.. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2015, 70, 64-71, 10.1016/j.brat.2015.04.010.

- Stig Poulsen; Susanne Lunn; Sarah I. F. Daniel; Sofie Folke; Birgit Bork Mathiesen; Hannah Katznelson; Christopher G. Fairburn; A Randomized Controlled Trial of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy or Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa. FOCUS 2014, 12, 450-458, 10.1176/appi.focus.120410.

- Susan Byrne; T. Wade; P. Hay; Stephen Touyz; C. G. Fairburn; J. Treasure; U. Schmidt; V. McIntosh; K. Allen; A. Fursland; et al.R. D. Crosby A randomised controlled trial of three psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine 2017, 47, 2823-2833, 10.1017/s0033291717001349.